1. Introduction

Agriculture is subject to constant economic, social, political, and technological changes. Many of these changes arise to solve problems in the field of agribusiness, to increase the profitability of the system and its competitiveness, and to reduce costs. In this context, agriculture starts to be perceived in a systemic way, with the agricultural business, through relationships intertwined in a complex system of activities and participants, called agribusiness [

1,

2].

In Brazil, agribusiness accounts for about 43.2% of the country’s total exports, providing economic growth, development, and competitiveness [

3]. Despite the great representativeness and importance, Brazilian agribusiness faces some difficulties, problems and risks in terms of rural activity [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The worldwide growing demand for Brazilian commodities, driven by countries with large populations such as China [

8], at the same time creates opportunities for Brazilian farmers in emerging markets [

9] and challenges them to overcome the logistic obstacles.

Among these obstacles and particularities are: (i) the bottlenecks caused by inefficient and inadequate distribution logistics and infrastructure problems [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]; (ii) exclusion and social conflicts [

15]; (iii) numerous, small, poorly organised, distributed and distant rural producers throughout the territory [

2]; (iv) production seasonality [

2,

16]; (v) perishability of agricultural products [

2]; (vi) weather, pests and diseases; variations in supply and demand; and (vii) difficult price and production predictability [

16].

Given this, Rural Collective Actions present themselves to face and circumvent the difficulties and particularities of the agricultural business and to achieve gains and advantages. Rural collective action can: (i) promote social, technological and innovative development; (ii) add value and create wealth [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]; (iii) assist in decision making; (iv) maximise the profit of associates and provision of goods or services [

25]; (v) is more efficient than disorganised individual actions [

26]; (vi) generate the dilution of activity costs [

27,

28]; (vii) assist in the commercialisation of and access to production resources for small farmers, provide technical assistance to members, access to market information, and provide an advantage with transport and storage [

29]; and (viii) provide a market advantage in the commercialisation of production [

30].

Thus, different models of Rural Collective Actions emerge [

8,

9,

22,

29,

30,

31], and each type of model has its characteristics and specificities. The variation may be due to the forms of association, size, incentives adopted [

25,

26], or dynamic nature [

32], and it is essential to understand the reasons for the variability between the different forms of Collective Actions [

32,

33].

Specifically, in this study, the collective actions are formed by social actors or groups that act as a collective [

17,

19], who can use experience for guidance, understanding, and set rules for actors participating in the action [

19], by considering common goals [

26]. These joint actions attempt to constitute a collective good, more or less formalised and institutionalised, through people who aim to achieve common goals through cooperation and competition with other collectives [

19].

Thus, the objective of this study is to investigate the emerging form of collective action of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses [

22,

31] under the lens of the Theory of Logic of Collective Action proposed by Mancur Olson (1965). In the context of rural collective actions, the inefficient distribution logistics and the shortage of warehouses in the country are the primary motivations for this study.

Mainly, this study empirically evidences collective actions and those social actors and/or rural producer groups that present themselves as collective subjects. It also provides evidence and criteria to guide, understand, and govern actions based on shared objectives. Thus, for the participants of this study, the joint effort is an attempt to constitute a collective good, more or less formalised and institutionalised, with people who seek to achieve common goals through cooperation and competition with other groups in distinct collective actions.

The Condominiums of Rural Warehouses is a unique collective action model in Brazil, which does not fit the characteristics of other forms of collective action. Usually, the problems of cooperation and free-riding arise in managing collective resources. The new model of rural collective actions, with an associative and cooperative character formed by neighbouring farmers, minimises the two previous problems. Rural producers collectively contribute financial and physical resources. Then, after constructing the warehouse, they share the structure by dividing them into storage quotas. This structure of shared financial quotas makes it possible to reduce the warehouse deficit and other logistical bottlenecks, mainly related to transportation. Besides that, co-producers reduce unnecessary costs, trade production without intermediaries and obtain advantages from the condominium and storage system [

11,

27,

28,

31,

34]. The paper shows that this collective rural warehouse management model succeeds because it follows the theoretical model of Olson’s Collective Action Logic. Literature on the subject is still scarce, and no study has, as of yet, analysed Brazil’s issue. Finally, Olson’s Collective Action Logic Theory explains the new rural management model related to the condominiums of rural warehouses.

2. Theory of Logic of Collective Action

Mancur Olson was an American economist and social scientist who studied social and political phenomena from economic models. “The Logic of Collective Action—Public Goods and the Theory of Groups” from 1965 stands out among his famous works. For Olson, the logic of collective action is based on the main idea that when there are common economic interests, individuals will come together to achieve common goals [

26] jointly.

In addition, common economic objectives are realised with greater strength and effectiveness through collective action and by promoting members’ interests [

26]. Collective actions are social interactions driven by collective goals, which generate joint actions to achieve them [

35].

For Maeda and Saes [

36], the logic of collective action occurs when economic agents, under cooperation, seek to maximise their satisfaction. The gain from collective action must be higher than that of an individual effort. In addition, the authors describe that the success of collective action has other factors, such as the size of the group. According to the authors, small groups present more satisfactory results for members, thanks to the ease of control and agility of actions.

Wenningkamp and Schmidt [

24] explain that the interests that Collective Action promotes must be attractive to all members, that is, members should share common interests. Collective actions aim to combine efforts through the joint action of individuals to achieve common goals [

24].

According to Olson [

26], smaller groups tend to achieve a collective benefit more easily and promote individual interest in the collaborative form. The larger the group, the more likely it is that the individual will reach the optimum goal of obtaining the collective benefit. Furthermore, the less likely he is to act to obtain even a minimal amount of that benefit. In short, the larger the group, the less it will promote its common interests [

37].

Thus, smaller groups have more advantages than large groups [

26]. According to the author, this is explained by small groups’ cohesion and greater efficiency and their social incentives and rational behaviour.

Smaller groups have greater strength of cohesion and efficiency, as individual efforts will influence the final results more so that individuals will contribute more to obtain or improve the benefits. If the group is larger, the strength of cohesion and efficiency of each participant will decrease, and the individual effort or contribution will not have much effect on the larger group [

37]. Because of these reasons, Olson reports that large organisations often seek subdivisions within the overarching organisation, creating small leadership groups in the form of committees and subcommittees.

In addition, economic incentives are not the only motivators for collective action. People are also driven by the “desire for prestige, respect, friendship and other social and psychological objectives” [

37]. These social incentives also work best in small groups, as people have greater proximity and knowledge between them. This proximity influences the individual to perform his duty or social role in collective action and to value his “friend”, social status, personal reputation, and self-esteem. Thus, small groups are favoured in two ways, first by economic incentives and second by social incentives [

26].

Maeda and Saes [

36] identified similar economic and social incentives characteristics during a Brazilian Rural Collective Action study. Economic incentives include economies of scale, increased bargaining power and dilution risk. As for the social incentives, the desire for prestige, respect, friendship and other social and psychological factors also appeared. It is worth mentioning that the economic incentives prevailed over the social ones in this study. The economic gain with the action is the main factor in maintaining the rural group [

36].

Moreover, Olson discusses the famous free-riders, when an individual group is favoured within the structure without contributing to the overall gain. In the study by Maeda and Saes [

36], they found that the occurrence of the free-rider is inhibited by the small group size and social incentive. Thus, the social pressure on the small rural group leads all members to comply and participate in actions to achieve collective benefit.

Wenningkamp and Schmidt [

38] found economic and social incentives to act collectively and environmental, cultural, and political motivations. For example, we can emphasise waste management and preservation of the environment, power in influencing decisions, commercialisation with the collective model, and recognition and rights in legal/political matters.

Olson [

37] briefly describes groups fighting for legislation favourable to their members, specifically for Rural Collective Actions. This is currently the case in Brazil, with large rural organisations, as an example of the strength of the ruralist bench, which has the power to influence politicians in Congress, the Organization of Cooperatives of Brazil (OCB), Brasilia, Brazil, or the National Confederation of Agriculture (CNA), Brasilia, Brazil, which exercise power over Brazilian cooperatives and agribusiness. However, it is not just for this reason that Brazilian Rural Collective Actions fight, motivate or structure themselves.

Iglécias [

23] and Ribeiro, Andion and Burigo [

20] discuss some historical aspects that influenced these changes. Iglécias [

23], in a study on the forms of collective actions and political articulation in Brazilian agribusiness, reports that Brazilian rural collective actions have been transforming since the late 1980s and early 1990s, due to a greater integration of the Brazilian economy with the world economy. Due to this reason, the country became more exposed to international competition, and as a result, farmers strengthened their positions through collective action. Ribeiro, Andion and Burigo [

20] state that from the 1980s, structural and socio-political changes began to occur in Brazilian agribusiness due to the re-democratization of the country and the promulgation of the 1988 Federal Constitution. Such changes passed more power to states and municipalities, increasing participation of society in the economy and politics and discussing such issues as social inequalities and preservation of the environment.

Olson’s theory approximates the new Brazilian Rural Collective Action model, called the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses. There is a shortage of warehouses for storing grain after harvesting in Brazil. Investments in storage are high and require a high level of financial resources. Farmers, after harvest, sell the harvest at the day’s prices so as not to incur losses. It would be possible to store the crop and to sell the produce at a later time. Given the supply risks in substantial crop failures and losses, the lack of grain warehouses is a food security problem. Thus, the Condominiums of Rural warehouse condominiums have emerged as a collective model to solve the problem. However, in collective resources, there is a free-rider problem. We discuss the model of the Rural warehouses condominiums in the following sections.

3. Materials and Methods

We carried out an applied, exploratory, descriptive and qualitative study. Besides conducting a literature review to gather the main variables related to the phenomenon studied, we conducted a case study associated with the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses. We conducted semi-structured interviews with the managers/owners of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses to collect data. We analysed the results through a Categorial Content Analysis under the Theory of Logic of Collective Action by Mancur Olson, also analyzing the results in relation to some studies related to the topic [

22,

27,

28,

31].

In related studies, such as a project supported by the Foundation of Support of Research of Distrito Federal—FAP-DF, Brasilia, Brazil [

11], the authors did not find any geographic record of the collective action model Condominiums of Rural Warehouses in Brazil. The leading Brazilian associations related to warehouses also were not aware of Condominium of Rural Warehouses, except those existing in Parana and Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, which were the subject of our study [

11]. Thus, the interviews were conducted by considering the representativeness of the existing condominiums obtained by documental analysis, mainly via the Internet and by phone, located in the States of Parana and Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. The choice of the study participants was made following the criteria of convenience sampling and accessibility. Prior contact was made by telephone, and the best day and time was scheduled, and the interviews were conducted in person. Condominiums of Rural Warehouses are disseminated by people who know the model and some reports are available on the Internet. When we interviewed the managers of the existing condominiums of Rural Warehouses in Parana and Rio Grande do Sul States, Brazil, we asked if they knew of other condominiums.

We carried out seven interviews in loco with the managers/owners of the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses in the municipalities of Palotina (C, E, F and G), Mercedes (B) and Francisco Alves (D) in the State of Paraná, and Ipiranga do Sul (A) in the State of Rio Grande do Sul, in Brazil. There is a greater concentration of this type of Collective Action in these municipalities.

We recognise that the choice of the participants of the study is a limitation of this paper; however, considering the difficulty in Brazil to have responses from questionnaires sent by e-mail [

11], the accessibility criteria had proven to be the more adequate in this case, considering the qualitative approach of our study. The results from the project’s final report supported by FAP-DF, Brasilia, Brazil, were also considered for the data collection and for accessing the study participants. We analysed the data through the lines and cluster meanings of texts through the categorical content analysis [

39]. The questionnaire was derived from the seminal works by Filippi [

27] and Olson [

26].

Finally, the selection of participants occurred through a pre-selection criterion that inhibited selection and information biases. The interviews were conducted impartially according to the questionnaire, were recorded and the interviewees’ testimonies were used to discuss the results.

In this sense, the Content Analysis had three stages: (i) pre-analysis; (ii) exploration of the material; and (iii) treatment, inference and interpretation (

Figure 1) [

39].

Pre-analysis is the material organisation stage, a careful and organisational phase, which aimed: (i) the choice of documents on the topic of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, for which literature on the subject is restricted; (ii) formulation of hypotheses and objectives, which is based on the Theory of the Logic of Collective Action for Condominium of Rural Warehouses and, (iii) elaboration of indicators and creation of semi-structured interview script to conduct the interviews with managers/owners. The exploration of the material aims to manage decisions through coding, discounting systematically or enumeration operations. In this second phase, the text of the interviews or documents is set into smaller units, with later categorisation. The categorisation is an operation that aims to classify common elements in sets, done before (

a priori) or after (a posteriori) data collection [

39].

The smaller units were the context of Condominiums of Rural Warehouse gathered from documents and primary data obtained with in loco interviews.

This study conducted categorisation after field research (a posteriori), elaborated on after the interviews. The categories proposed are (1) Collective Action Model of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses; (2) Rural Collective Actions; (3) Economic and Social Incentives for Condominiums of Rural Warehouses; (4) Small Groups and Large Groups; (5) Determining Factors of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses; and (6) Perspectives of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses. Finally, the last step was the treatment of the results and the presentation and discussion of the data.

The last stage of content analysis comprised the treatment of results, inference and interpretation of data through qualitative analysis, including the transcription of primary data interviews, analysis of documents provided by condominiums of rural warehouses, and a discussion of the results in light of the theory of Collective Actions.

Moreover, we triangulate data to compare results from different instruments of data collection (interviews, observation, documents and theory) and the opinions of the other managers/owners of the condominiums of rural warehouses. Among the advantages of triangulation is the establishment of truth, improvement of theories, confidence, accuracy, quality, elimination of bias [

40] and more robust contributions [

41]. We present the results in the following section.

It is noteworthy that there is still no national registry of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses. Thus, the sampling took place for accessibility and convenience. In Brazil, a national registry shows the warehouse units in the territory. Such registration is conducted by the Brazilian government’s National Supply Company (CONAB), Brasilia, Brazil. However, CONAB’s registration differs between cooperative, private or official warehouse units. There is still no specific survey or classification regarding Condominiums of Rural Warehouses.

We found that the knowledge on Condominiums of Rural Warehouses in Brazil is still insufficient, considering the perceptions of some entities, producers or associations dealing with agribusiness and warehousing. The data from “Project financed by the Foundation of Support to Research in Distrito Federal, Brasilia, Brazil (FAP-DF) carried out between 2017 and 2019 in the Distrito Federal and surroundings corroborated this information. This model of collective action is best known in the Southern Region of Brazil, and more specifically in the city of Palotina, in the State of Paraná. Based on television reports or informal contact, some farmers or entities seek information in the area of Palotina or scientific publications.

In the case of the Brazilian Agriculture Confederation (CNA), Brasilia, Brazil, an entity representing rural producers in the country conducted a meeting to present the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses model, by researchers from universities to 27 representatives of Farmers’ Federations in the 1st half of 2019. The representatives were optimistic about the model and became aware of the new Brazilian Rural Collective Action model.

Furthermore, we found that the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply of Brazil (MAPA) and the Technical Assistance and Rural Extension Company (EMATER headquarters, located in Brasilia, Distrito Federal, Brazil), were not aware of the topic. It is essential to point out that the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses model is relatively new. There is insufficient knowledge about the country’s territorial extension and a poor dissemination of information among producers, entities, researchers, and the government. Thus, the model is better known in the country’s Southern Region. From 2016 to 2019, in Palotina, Paraná, Brazil, a further three Condominiums of Rural Warehouses were built, totaling six in Paraná by 2019. Thus, this study considered seven Condominiums of Rural Warehouses known in the country: (a) Warehouse Condominium “A” in the city of Ipiranga do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul; (b) Warehouse Condominium “B” in the city of Mercedes, Paraná; (c) Warehouse Condominium “C”, “E”, “F” and “G” in the city of Palotina, Paraná; and (d) Warehouse Condominium “D” in the city of Francisco Alves, Paraná.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Model of Collective Action Rural Warehouse Condominium

The first category aims to present the collective action model of the Rural Warehouse Condominium.

The collective action of the Rural Warehouse Condominium is an association of farmers that share the same objective, storage. In the specific case, the model aims to store grain production in warehouses, shared among all partnering farmers and divided into storage quotas through internal regulations and a set of rules (statute). In addition, the partner farmers own the unit, which comprises the storage units (Metal Silos) and the administrative building, reception and scale, warehouses (hoppers, cleaning machines, dryer, tipper, furnace, etc.), and another small area available. The whole complex is the Rural Warehouse Condominium in approximately 6 hectares.

Initially, the Condominium assumes that farmers alone cannot make the Warehouse financially viable. Additionally, when they come together collectively, the viability of the Warehouse becomes possible since the costs are shared among all partners.

Olson [

26] reports that the formation of groups begins with a common and primary purpose, in this case, the collective storage structure for the Warehouse Condominiums. In addition, the creation of the Condominium corroborates the economic objectives that can be realised with greater strength and effectiveness through collective action.

The model achieves other common goals by collectively making the storage structure viable. Obtaining more significant profit from the sale of the product, minimising costs, adding value to the product, strategic marketing of products, by reducing logistical bottlenecks, rural activity and commercialisation are other incentives for the formation of the collective group Rural Warehouse Condominium, which meet the economic objectives of the Theory of Logic of Collective Action.

Table 1 exemplifies some of these statements.

It is worth mentioning that the strategic commercialisation of production is one of the main factors in creating the Rural Warehouse Condominium reported by the interviewees. When marketing their products without the Condominium, farmers reporting having had a reduced profit margin and were often forced to sell the product right after harvest since they did not have places to store their products. Thus, with an ample supply of the product on the market, usually during harvest periods, the prices of the products end up being lower than in the off-season due to supply and demand.

In addition, the price paid to the producer to deliver the product to third-party warehouses is less than that negotiated at the Condominium. The price received for the product through the Condominium is around 11 to 20% higher. In addition, the sale through the Condominium excludes middlemen. The deal is carried out directly with the buyer or trading company, and the profit increases for the farmer.

In addition, respondents noted the importance of the small number of farmers in each Condominium. Each condominium has around 8 to 24 farmers, with an average of 16 farmers for storage condominium and the productive area around 4500 hectares storage capacity revolving around 450,000 bags of 60 kg (27,000 tons).

As in the case of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, small groups have more satisfactory results due to the ease of control, agility of actions, greater cohesion and greater efficiency, and achieving the collective benefit more quickly. Other aspects such as respect, friendship and characteristics of a social and psychological background are also incentives for collective action and the good functioning of Collective Action [

37].

In addition, the existence of a small and restricted group is a determining factor for success for the Rural Warehouse Condominiums model. At the point of deciding to set up the Condominium, the farmers had already known each other, had confidence among themselves, and had similar profiles and ideas that contributed to the smooth running of the model’s activities.

In this context, the small group must be well structured and organised, financially stable, and have prior knowledge and/or experiences in collective actions for the model’s success.

Another vital characteristic of Condominiums is the profile of the farmers. Small and medium farms prevail in the Condominiums. It is worth explaining that the profile of farmers in Brazil is different, especially when comparing the South region and the Midwest region, the central grain-producing regions in the country.

The small and medium producers in the South region can vary between 100 to 300 hectares. The large farms are over 1000 hectares. In the Midwest region, small farms have at least 1000 hectares. Thus, the Southern region is characterised by farms with small agricultural areas. This characteristic is for forming a Condominium of Rural Warehouses, as a prominent owner of the Midwest region, in economic terms, can easily make his storage viable. However, in the South, this would not be possible.

This fact is reflected in the incentives for making the model viable. Still, it does not exclude other motivations, such as the social and economic ones that the model provides and will be discussed in the third category.

4.2. Rural Collective Actions

The second category reveals perceptions and characteristics regarding the different rural Brazilian collective actions.

Among the different Brazilian rural collective actions, the interviewees know the Associations, Cooperatives and Rural Warehouse Condominiums. As for the Cerealists, the interviewees know. However, it is not considered a rural collective action, as only one owner buys and sells grain.

Respondents also reported the prevalence of large Cooperatives in Palotina/Parana and Rural Associations, Brazil. There are fewer rural condominiums, with around six in Palotina/Parana and one in Ipiranga do Sul/Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Associative and cooperative culture is predominant in the country’s Southern Region, which creates and develops collective actions.

As for the diversity of agricultural activities in Rural Condominiums, most interviewees know only about the storage segment. Interviewee A reported some form of a Swine Condominium in Salete, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, but that the Collective Action did not work due to administrative problems, and today it is private. Interviewee B reported knowledge of the Agroenergy Condominium in the municipality of Marechal Rondon, state of Parana, Brazil (Ajuricaba Condominium) and another Agroenergy Condominium that began recently in the municipality of Entre Rios do Oeste, state of Parana. Both transform pig waste into bioenergy through a biogas plant. In the literature, it is possible to notice recent studies with Condominiums of Agroenergy [

42,

43].

Slightly different from bioenergy production from swine manure, interviewee C reported building a Solar Energy Condominium to reduce the electricity costs of the Warehouse Condominium and supply the rural properties themselves.

In contrast, interviewee F commented on the idea of a Silage Condominium sharing Silage machines, which would reduce investment costs and bring greater efficiency to the production process. On the other hand, Interviewee E reported only hearing about a Milk Condominium in Mangueirinha, Parana, Brazil, which delivers the product to the Cooperative.

In the literature, it is possible to notice a diversity of Rural Condominiums. Noteworthy activities include agroenergy [

42,

43], logistics (warehouse) [

11,

22,

27,

28,

31,

34], coffee-growing [

44], dairy [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], and pig farming [

47,

50,

51]. However, studies on the subject are still recent and few.

In addition, among the different rural collective actions, around 80 to 90% of the farmers in the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses participate in other models, such as Credit Cooperatives and Agroindustrial Cooperatives. There are cash loans (financing), purchase of inputs, and sale of products in these relationships.

We noted that rural producers need to associate themselves with collective rural action. Interviewees C and B added: “Now, not associating with anything is bullshit…”, “rural collective actions for agribusiness are critical, there should be more”, respectively. In the Theory of Logic of Collective Action, collective action is more efficient than disorganised individual action. Thus, the rural activity carried out collectively is more efficient to the processes and objectives of everybody.

Fonseca and Machado-da-Silva [

52] and Garrido and Sehnem [

4] also corroborate the importance of Collective Actions in competitive and fierce business environments to face competitive scenarios and the survival of institutions strategically.

For Saes [

25], collective action achieves the individual interests of each person. The objectives are more easily achieved, and the associates’ profit is maximised, goods or services are provided, the “rules of the game” are changed, and conflicts are resolved.

Thus, the interviewees’ unanimously asserted the importance of collective rural actions for agribusiness and the whole production chain. We can highlight the security, aggregation of value to the product, generation of jobs, dilution of costs, a gain of scale, quality of food, marketing increase in profit and use of technologies as main advantages.

With this, interviewee E commented on the importance of farmers staying together because rural collective actions cannot be achieved if there is no union. Likewise, interviewee G said that soon he sees the formation of an Association between Condominiums of Rural Warehouses to ensure greater representativeness of the category and seek better financing conditions, such as lower interest rates, as different needs may arise.

In addition, for the rural producers of the Condominiums, the viability of the storage structure and the extra profit obtained from direct sales and strategic marketing were only possible thanks to the cooperative union of producers. “I was always very accountable and was not viable alone. I was going to have a high maintenance cost to play alone, and in this collective way, I think it went well” (interviewee B); “…what changes are for the groups that make it up, who manage to have a slightly higher final gain in his currency, which is the grain” (interviewee A).

The “surplus” with the sale of the products (grains) directly to the market, without intermediaries in the transaction, and the possibility to sell the product at any time of the year, especially in the off-season when the price of the product is best, are the main benefits. This condition is possible considering the Condominium’s capacity of storage.

In addition, the rural collective action models differ from each other. The Condominiums of Rural Warehouses differ from the other collective actions because it is driven to a smaller, non-business group, with a limited warehouse share, and less bureaucratic.

Table 2 summarises the advantages of the Rural Warehouse Condominium model over other rural models.

In addition, the difference between the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses and other Brazilian Rural Collective Actions is that the farmer owns his grains, since the warehouse is his and he can choose the best time to sell his product and product quality. Complementarily, the participants of condominiums of rural warehouses have greater decision-making power in meetings. Concerning their product, they also have the autonomy to decide when it will be sold and to whom, that is, they can negotiate better prices for it, as opposed to selling at over-the-counter prices offered in other rural collective actions without negotiation.

Decisions and management in smaller collective action models are also faster and more agile, as in Warehouse Condominiums. There are tax advantages over other models, as they are not companies; condominiums do not receive discounts.

Concerning the problems of agro-industrial logistics, such as deficits in warehouses and queues for loading and unloading, the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses avoid these problems. Considering that there are few partners in the Condominium, the flow of loading and unloading in the silos does not generate queues. In addition, each partner has their share of storage, so each producer knows the space available to store their products in the Condominium silos. Suppose space is lacking, depending on the crop years or increases in production. Farmers can use the quota of another partner. When the managers/owners of the Condominium decide it is possible to expand the storage capacity they can construct new silos.

4.3. Economic and Social Incentives for Rural Warehouse Condominiums

The third category discusses the role of Economic Incentives and Social Incentives in front of Rural Warehouse Condominiums, motivating bases for forming groups according to the Theory of Logic of Collective Action.

First, respondents almost unanimously agreed about Economic Incentives relating interest rates to warehouse financing (

Table 3). When asked about the role of Economic Incentives in forming groups, we discussed two relations: Governmental economic incentives and market-based economic incentives.

The governmental economic incentive applies because the Government restricts contributions with financial incentives to the collective action model of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses. Mainly to incentive programs for the construction or expansion of Warehouses with competitive interest rates for small and medium rural producers.

Currently, the central government program available for Warehouses is the PCA—Program for the Construction and Expansion of Warehouses—with interest rates ranging from 6% to 7% per year, 6% for investments with a grain storage capacity of up to 6000 tons and 7% above that [

53]. According to the interviewees, interest rates for farmers are high. They have risen over the last decade, mainly for small and medium farms, being a disincentive for structuring new Warehouse Condominiums and new construction of storage units in the country.

It is worth remembering that there is a storage deficit in the country and obsolete storage units that need modernisation. At a more favourable time, the lack of warehouse spaces still implies not enjoying storage benefits, such as product conservation and commercialisation.

In addition, we asked the interviewees about the non-knowledge about the model of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses by the Government. So, we perceive a need for greater articulation between governmental economic and social agents to learn about the country’s reality and outline economic and social incentives for this emerging Brazilian rural collective action model. This articulation is essential given the model’s contribution to reducing the warehouse deficit, greater product competitiveness, regional growth and development for agribusiness and municipalities, and money turnover in the country’s economy.

In addition, on the economic incentives of a market order, the extra profit that rural producers have when marketing production with the Rural Warehouse Condominium is exemplified: “The main differential, economic incentive, would be the spread, which the Condominium gains with selling the grains owned by farmers” (Interviewee G).

This characteristic shows the extra gain with the owner’s product when selling his production through the Condominium, without an intermediary in operation. Even stored, the producers keep the property of the produce (grains) because the participants own the silos. This gain can vary between 11 to 20% more per grain bag, depending on the time of year.

It was also verified that Government economic incentives are unattractive and insufficient for the country’s construction and development of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses. However, concerning market economic incentives, mainly about the extra gain with the product in strategic marketing, there are favourable scenarios for Rural Collective Action, solid determinants for the rural model.

In the Theory of Logic of Collective Action, economic incentives are paramount for forming groups. If there are no economic incentives, a group does not survive long term, and there is no reason for the activity to remain in the market. Thus, producers’ additional gain in marketing the product through the Condominium is a condition for the organisation to survive and promote its members’ interests. However, high-interest rates for the financing of condominium warehouses have hindered the rural model.

Maeda and Saes [

36] consider that Economic Incentives are superior to Social Incentives. Thus, the economic gain from the rural activity is a fundamental condition for the group to survive in the market.

Economic Incentives are not the only determinants for forming groups under the Theory of Logic of Collective Action. There are also Social Incentives, such as prestige, respect, friendship and social and psychological characteristics that encourage people to organise themselves into groups. These characteristics are evident in the collective actions of the Rural Warehouse Condominiums.

Table 4 illustrates the social incentive.

Social incentives were highlighted by the interviewees, including greater interpersonal relationships; exchange of knowledge, information; technical and professional growth; job creation; learning among the Condominium’s professionals and farmers, etc. Note the diversity of social incentives generated with the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, which strengthen the rural movement and benefit from the interaction between all model members.

The Logic of Collective Action describes the “social pressure” in-group behaviour with Social Incentives. There is a set of rules in Condominiums of Rural Warehouses Condominiums, which is the model’s Statute. The farmers’ efforts and the model follow the Statute. In addition, each producer and/or employee is willing to help and collaborate with whatever is needed in the Condominium of which he is part. The demands are not binding, but rather, because the rural producers own this model and know each other, everyone collaborates in meeting the needs that may arise.

In addition, at Condominium meetings, everyone freely expresses their ideas, respects themselves and actively participates in the model. Interviewee A also reports that the rules and responsibilities are more “easily enforceable” in the smaller group, the Condominium.

For Olson, “social pressure” makes it easier to fulfil individual obligations in smaller groups due to the appreciation of the company of friends and colleagues and the zeal for social status, social prestige and self-esteem. The author reports that the social incentives and “social pressure” only work in small groups so that each member has “face to face contact with all others” [

37]. In this sense, Social Incentives favour Condominiums in smaller groups.

4.4. Small Groups and Large Groups

The fourth category analyses the characteristics of rural collective actions between small and large groups. According to the Collective Action Logic Theory, smaller groups have more advantages over larger groups, smaller groups are more efficient and effective, and social incentives work better in small groups.

Table 5 delineates the main aspects regarding the rural collective action model of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, notably a small group.

It is possible to notice characteristics that distinguish small and large groups and that stand out in small groups. Small groups are treated in this study as groups of up to 25 people (production around 4500 hectares, that is, 315,000 bags of 60 kg, with 70 bags yield per hectare on average). Large groups would already have 100 and 200 members (around 2.5 million bags of 60 kg).

This distinction is considerable for the development of Rural Warehouse Condominiums since this condition implies the efficiency of the progress of all Collective Action activities, including the financial return to maintain the model itself. According to interviewee A, a Condominium of Rural Warehouses can be small or large. Since it is tiny, and has low production it would be unfeasible to pay for the entire structure of the Condominium, which includes expenses such as energy, employees, maintenance, etc. On the other hand, a large producer could have its storage structure on his farm. In this way, he would make the installation costs viable individually. It is worth remembering that the Condominium model brings other advantages, not only the feasibility of own storage.

The small group still presents the advantage of the social characteristic for all members, a strong point described in all statements and meets the Theory of Logic of Collective Action regarding Social Incentives. Smaller groups achieve collective benefit more easily than larger groups; Social Incentives work best in small groups. Since the smaller the group, this fact occurs, the easier it is to reach the optimum point of getting the collective benefit. That is why larger organisations form small groups, smaller subdivisions [

26].

According to the testimonies, a group with fewer people has fewer different opinions. Thus, it is easier to reach a consensus, and more occasional disagreements will arise.

In addition, small group participants start from the same common goal more simply. This aspect is more satisfactory in smaller groups. Smaller groups are more easily controlled, people know each other better, organisation and communication are easier, and the small group is more united and of greater affinity.

Other advantages prevail in small groups, such as in Warehouse Condominiums. The main benefits of the model are as follows: greater agility in decisions, speed in unloading and absence of queues at the silo, higher profit margin (product quality and direct sales), better prices and conditions in the purchase of inputs, express their opinions in the group for being smaller, logistical proximity to storage with ownership, and being the “owner of your product” provide freedom in marketing.

Individual action is also better recognised in smaller groups. In the Theory of Logic of Collective Action, this occurs since, in large groups, the typical participant knows that their efforts will not influence the result too much. He will be affected in the same way by the final decisions. Thus, individual effort in larger groups will not influence the decision. In smaller groups, the personal effort reflects more on the final decision.

Another fact identified in the collective rural models was the market competition between small and large groups. Even before the existence of Rural Condominiums in the region, large groups prevailed, which held 100% of the sales and associates. With smaller groups in the area that are similarly competitive or more, there is more competition among the different associative forms. This fact is positive for the end customer since, in more competitive markets, groups must always seek their best quality products and strive to be a more efficient and effective organisation. Otherwise, the client or associate will look elsewhere for these qualities.

Furthermore, for small groups, access to rural credit and bargaining power may be more challenging to achieve. Financing requires guarantees from the rural producers. Therefore, they must come together to fulfil this criterion needed for the banks to finance the storage structure. High-interest rates aside for small producers. Together, to gain more bargaining power and scale, smaller producers must come to achieve these goals. In larger groups, such aspects are more easily achieved.

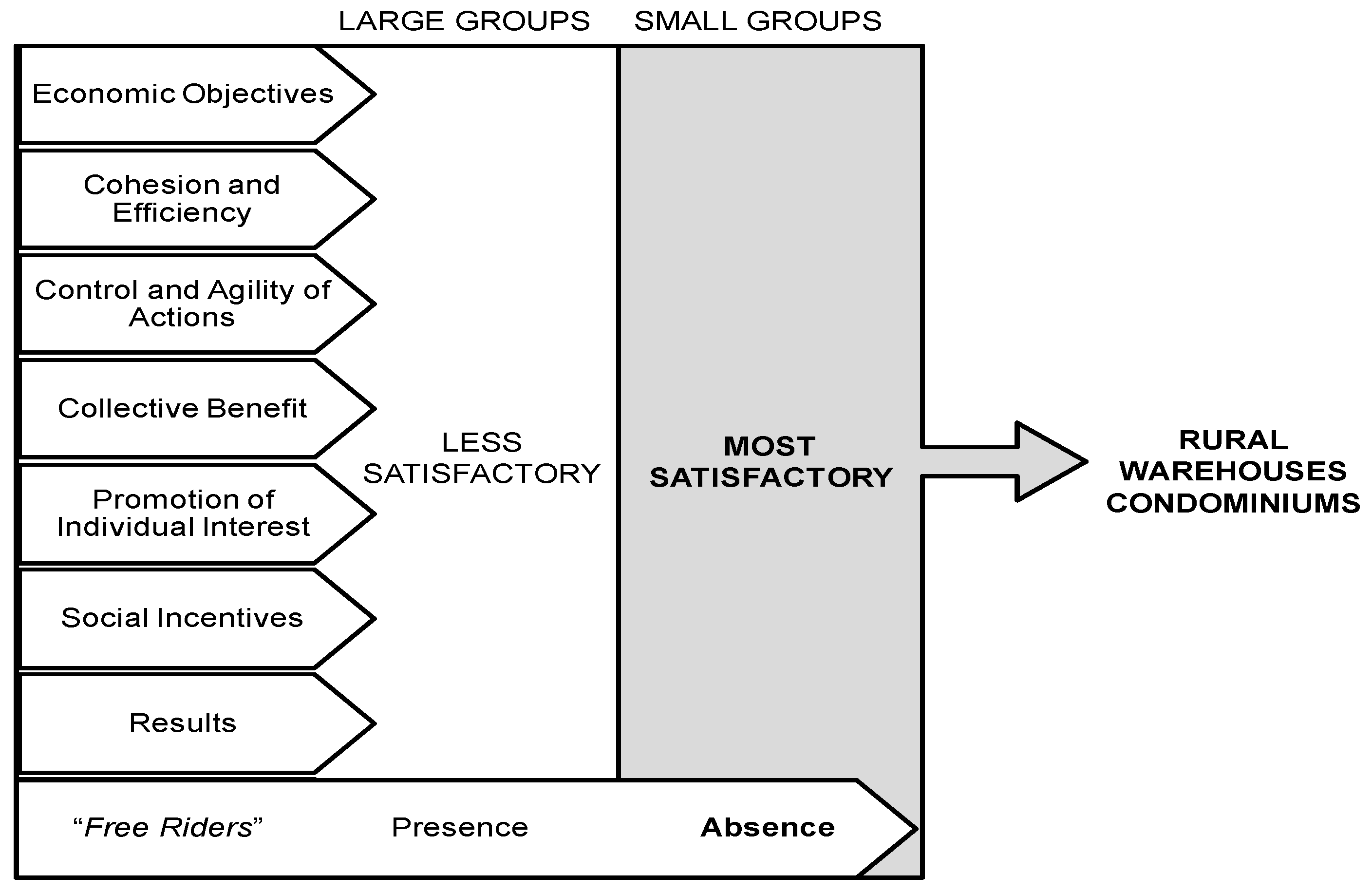

Finally, it is possible to highlight the main differences between small and large groups according to the Rural Collective Action of Rural Warehouses Condominiums and the Theory of Logic of Collective Action (

Figure 2).

Based on the results, we verified that in small groups, such as the ones forming Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, the economic and social objectives, the control and agility of actions, the promotion of individual interests, cohesion and efficiency, and the results are more satisfactory than in large groups. Additionally, it is noteworthy that there are no free-riders in small groups, since everyone participates actively, knows each other and are driven by friendly relationships alongside Social Incentives, which are more easily attainable in smaller Collective Actions.

Finally, for a small group to be successful compared to larger groups, it must be well structured, organised, and financially supported. In the case of Condominiums of Rural Warehouse, the rural partner producers already belonged and/or knew models of collective actions, such as Cooperatives and other types of Associations. In this way, they already had practical and prior knowledge about collective effort to make the collective action Condominium of Rural Warehouse model works correctly.

4.5. Determining Factors of Rural Warehouse Condominiums

The fifth category qualitatively discusses the main determining factors for Condominiums of Rural Warehouses.

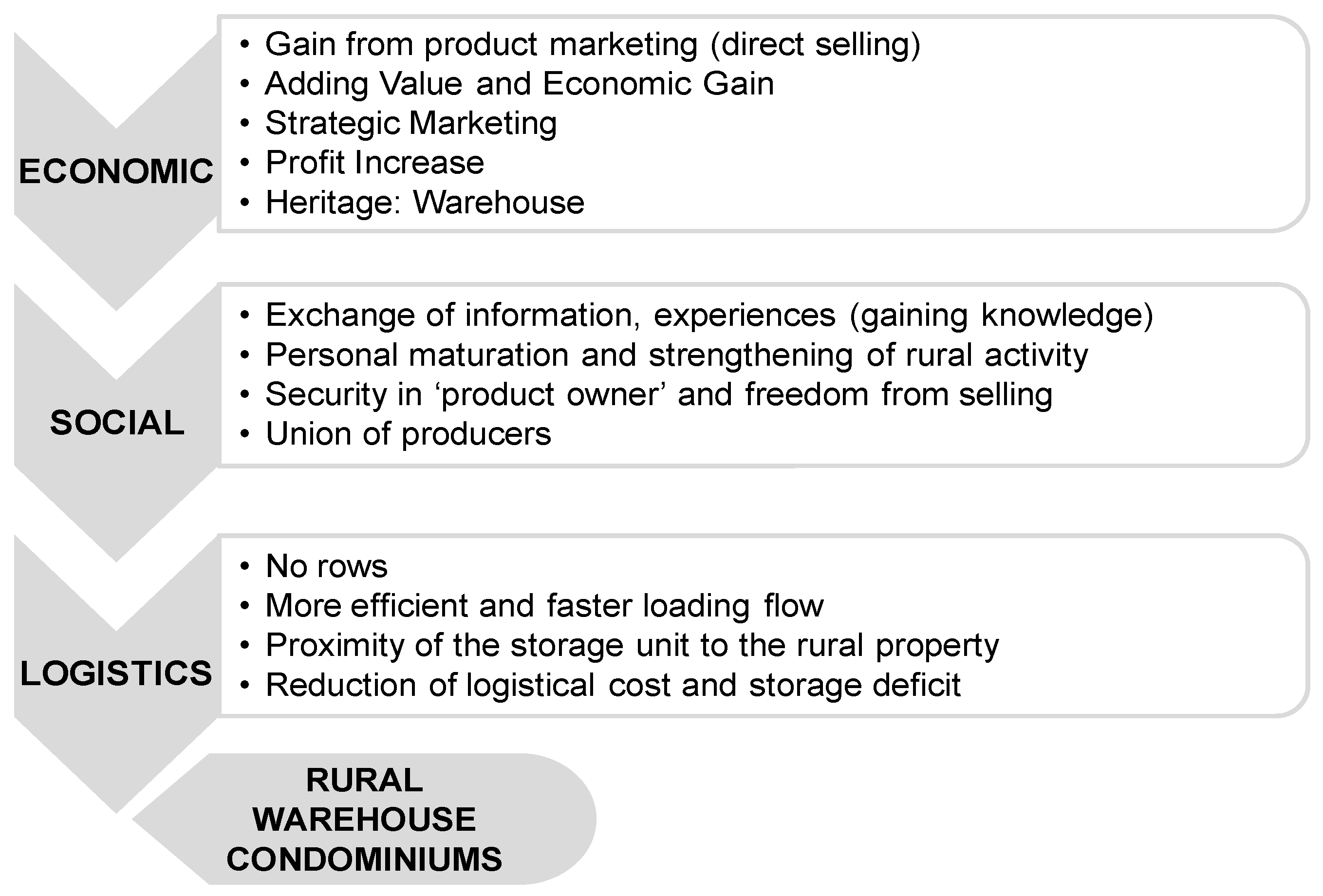

Some factors repeated the testimonies of charges and went against Economic Incentives and social conditions for forming groups. The advantages with the product commercialization, direct sales and superior profitability—the added value, the logistical gains, no queues, less flow and proximity of the storage unit to the rural property—and the social gains from the model of collective action are decisive benefits for Rural Warehouse Condominiums.

Figure 3 presents the significant economic, social and logistics determinants for forming the condominiums of rural warehouses.

In the economic determinant group, one of the main motivating characteristics for structuring rural collective action is illustrated, which is the economic gain with such activity. This characteristic is remarkable for forming groups according to the Logic of Collective Action. Having its warehouse structure, understood as an extension of rural property, allows the rural producer to sell his products directly, without intermediaries in commercialisation, and at a reasonable time for him, causing an increase in his profit and adding value to the product, through the collective model and the best quality of the grain. It is worth remembering that the warehouse also belongs to the rural producer, which means that it is his property. This characteristic differentiates the Condominiums from other Brazilian Rural Collective Actions. Additionally, it guarantees the power of negotiation of the producers and dilution of costs between all partners.

We obtained these characteristics through the following main motivating economic factors highlighted by the interviewees: “security of having your product in your warehouse”, “adding value”, “storing and selling the product”, “economic gain”, “increased profitability” and “product commercialisation” (

Table 6).

As social determinants for the structuring and development of Rural Warehouse Condominiums, the main factor is the importance of unity among producers. This characteristic is a condition for the creation and development of Condominiums. All producers act as partners with each other, have good relationships and share the same ideas. Common goals are essential for the business to be entirely successful.

Along with these social aspects, the rural producers belonging to the Condominium gain from exchanging information and experiences, thereby generating knowledge. Throughout such activities, producers still enjoy personal maturity and strengthen rural activity, which also leads to advantages in local growth and development. Again, Olson [

26] describes that social incentives are more easily achieved and work better in small groups, as with Condominiums.

Finally, as to the logistical determinants, the Rural Warehouse Condominiums circumvented some logistical bottlenecks faced by rural producers, such as queues at third-party storage units, mainly in peak seasons. Thus, the model provides better efficiency in the loading and unloading flow and reduces the storage and logistics deficit.

4.6. Perspectives of Rural Warehouse Condominiums

The sixth and final category comprised the rural collective action model Rural Warehouse Condominium in Brazil.

The knowledge of the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses is restricted to the South of the country, mainly in the region of Palotina in the state of Parana, Brazil. Even the Condominium managers are unaware of other Warehouse Condominiums in other cities or areas of the country, including the Ipiranga Condominium and the Condominiums in the Palotina region, which are not known.

However, there are favourable scenarios for implementing new Rural Warehouse Condominiums, mainly for small and medium producers and places where there are logistical bottlenecks and storage deficits. This would be useful for rural producers who aim to enjoy the advantages of the condominium model, such as storage itself.

The interviewees provide some critical characteristics for the success of collective action of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses and for them to develop in other regions, such as (i) profile of the rural producer, producers who are unable to make their storage structure viable, or who seek be in some Rural Collective Action; (ii) regions with an associative culture and/or places where cooperatives or rural collective actions already exist; (iii) the group must have confidence and an entrepreneurial spirit; (iv) all farmers will be responsible for the smooth running of the model; (v) have a neutral, reliable figure with knowledge in agribusiness and marketing to manage and sell the products of the farmers (Condominium manager); and (vi) ascertain the production and storage needs of each partner before setting up the Condominium.

Table 7 summarises some excerpts from the interviewees’ statements on these aspects.

In turn, the Condominiums of Rural Warehouse model is more sought after by people from the regions of origin of the Condominiums. Still, there are also interested parties from other areas of the country. The target audience is usually made up of farmers who have heard of the model, are looking to visit the existing Condominiums of Rural Warehouses to understand how it works, and to assess its viability.

Interviewee C reported interest and visits from different persons to learn about the model, from farmers, people from other states, and companies that sell silos. Interviewee D also reported the disclosure of Condominiums by companies that sell silos and reported having been visited by students from the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), Parana, Brazil so that they could learn about electrical specificities as students of Electrical Engineering and agricultural colleges in the region, acting as temporary interns.

Complementarily, there was an expansion of this rural collective action in other municipalities in the South region. The interviewees are aware of new Condominiums of Rural Warehouses under construction. Some of them are in the vicinity of Marechal Cândido Rondon (Parana, Brazil) and Não-Me-Toque (Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), and in the municipalities of Nova Santa Rosa (Parana, Brazil), Terra Roxa (Parana, Brazil) and Sapezal (Mato Grosso, Brazil). However, other states have already sought information, such as Minas Gerais and Mato Grosso do Sul. The interviewees cannot say whether Warehouse Condominiums have been established in these locations.

Furthermore, regarding the long-term success of the model, it is crucial to define the set of condominium rules (by laws), the issue of leaving members or family succession/death of a partner. It was noted that the topic could generate conflict between partners if it is not managed in a transparent and equal way among all. Thus, it is vital to set clear rules regarding whether the Condominium allows the sale of the storage quota, its valuation and who has the privilege of buying, for example, if another partner can purchase the quota or if external member of society can.

Finally, Government economic incentives become motivators for the creation and development of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, mainly via financing programs for storage, which is in line with the profile of the rural producer and compatible interest rates. Together, the profile of the rural producer is consistent with the model, since smaller rural producers who are unable to access a storage structure are eligible to become part of the Rural Warehouse Condominium model and can enjoy the other advantages that the collective action brings.

As a dimension of the rural model Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, we suggest that collective action should meet the productivity needs and static storage capacity of partner producers, should have the capability to expand and should be financially viable for all members.

Considering the perspectives of the managers/owners of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses and some findings of this study, we identified the owners’ demands and perspectives with other types of Rural Condominiums. Some examples include the Energy Condominiums to reduce energy costs from a sustainability perspective; the Silage Condominiums share machines and generate greater efficiency and reduce costs. Both models do not yet exist. Only Agroenergy Condominiums transform animal waste into bioenergy; thus, we suggest technical and financial feasibility studies on the topics.

5. Condominiums of Rural Warehouse under the Lens of the Theory of Logic of Collective Action: A Reflection Based on Content Analysis

The Logic of Collective Action theory clearly shows that collective action can arise at the moment that a number of individuals have common economic objectives. This argument is clear to the Rural Warehouse Condominiums.

The small group of rural producers with common economic objectives is present through storage in the rural collective action model. Rural producers, with the objective of establishing warehouse structures, taking advantage of the condominium system and storage, and circumventing logistical bottlenecks led to the creation of rural collective action in Brazilian agribusiness through the sharing of storage quotas.

The model is suitable for a small group, of between 8 and 24 rural producers, who produce in an area of 4557.14 hectares on average, and capable of generating revenue through the sale of production and storage. Thus, there is a financial and economic condition to make the storage structure viable and maintain the Condominium costs over the long term.

In addition, the producers who belong to the Condominium already had experience and/or knowledge in other forms of collective actions, and many farmers were already part of different types of cooperative models. However, the Condominiums of Rural Warehouse differ from other models by making the warehouse structure a common asset for all rural partner producers. Besides that, promoting the strategic commercialisation of production, direct sales of the products (grains), superior profit from the sale, its characteristic as a less bureaucratic model, greater decision-making power over their product, reduced queues in the loading/unloading of the warehouse and enter the unit. The producers own the storage structure itself, and individually. The warehouses would not be viable for small and medium producers outside the model.

In this context, small, restricted and closed groups, as in the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, is a determining factor for the success of collective actions. Relationships of trust and friendship between the partners, with similar profiles and ideas, contributed to the smooth running of the model’s decisions and activities. Small groups of rural grain producers organising themselves in Condominiums of Rural Warehouses are more likely to overcome their latency when realising that the benefits of cooperation outweigh the costs of achieving the physical storage structure. In this way, everyone assumes the cost of providing the collective warehouse.

Notably, the structure, good organisation and transparency, together with a neutral figure to manage the model, and financial and economic conditions, promote Condominiums of Rural Warehouses’ longevity and growth and competition in Brazilian agribusiness.

It is worth noting that the country’s political and economic conditions can encourage the structuring and expansion of this model. However, particularities related to each region should be considered. Government incentives, such as interest rates, rural credit and financing programs for the warehouse and the profile of small and medium-sized rural producers, are incentives for the viability of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses.

With the Collective Action Logic Theory, Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, formed by a small group, have greater benefits than larger groups. Olson [

26] argues that small groups reach the optimum point of obtaining the collective benefit more easily.

Thus, economic objectives, cohesion and efficiency, control and agility of actions, collective benefit, promotion of individual interest, social incentives, results and the mitigation of free-riders are more satisfactory in small groups. The small group also has fewer opinions, diverges less, is easier to control and organise, and decisions are more agile and easier to make. Therefore, small groups have more advantages over larger groups.

6. Conclusions

Under the lens of the Theory of Logic of Collective Action, this article discussed and analysed aspects of rural collective action Condominiums of Rural Warehouses in the context of Brazilian agribusiness. An approximation of the Condominium Rural Warehouse concept is observed with the Theory of Logic of Collective Action, mainly considering the logic and characteristics of small groups.

Condominiums of Rural Warehouse under the analysis of group formation provide numerous advantages, such as making the warehouse structure collectively viable, strengthening the collective, providing greater efficiency for rural businesses and producers, allowing for the insertion and integration in a competitive market environment, economic benefits, a reduction of costs and increased profit.

The theory explains that besides the non-existence of free-riders, in small groups, the economic objectives, cohesion and efficiency, control and agility of actions, collective benefit, social incentives, results and the promotion of individual interest are more satisfactory.

In addition, based on the Content Analysis, it was possible to establish categories to analyse and discuss the model Condominium of Rural Warehouses under the lens of the Theory of Logic of Collective Action. The warehouse is revealed as the core of the common goal to all farmers. Some benefits are the feasibility of the warehouse structure, dilution costs, realisation with greater strength and the effectiveness of economic goals, obtention of greater profit (direct sales and strategic marketing), reduction of costs and logistical bottlenecks, and aggregation value to the final product. In addition, the Condominium of Rural Warehouses model is formed by a small, restricted and closed group, with a profile of producers ranging from small and medium to the Southern Region, with experience in other models of rural collective actions, as well as relationships of trust and similar ideas.

Regarding the different collective actions in the Brazilian agribusiness, the Cooperatives and Rural Associations that work in storage, agricultural, livestock and rural credit activities stand out. In addition, there are Rural Condominiums, a little-known and lesser-proportioned rural collective action, which operate in different rural industries, such as storage, dairy, pork, coffee and agroenergy. The associative and cooperative culture is predominant in the country’s Southern Region, which creates and develops collective actions. Additionally, we see the importance of uniting and forming collaborative groups for local growth, development and agribusiness so that individual objectives under collective action are more easily achieved and more efficient, promoting advantages for the individual, the business and the whole value chain.

Among the main differences between the Warehouse Condominiums and the other rural collective actions, the following stand out for the Condominiums: strategic marketing, direct product sales, higher profit from the sale, owning the storage structure itself, a less bureaucratic model, efficient, greater decision-making power for rural producers, and a reduction of queues for loading and unloading.

Government Economic incentives restrict Condominiums of Rural Warehouses due to the uncompetitive interest rates and high profile for small and medium farmers. In addition, interest rates have increased over the years, discouraging the viability of new warehouses and making storage financing “expensive”. It is worth remembering that a storage deficit persists in the country. The lack of warehouses leads to a failure to enjoy the advantages of storage and causes stagnation in the storage sector, silos and similar companies, and for any collective actions involved.

On the other hand, market economic incentives include extra profit provided by direct sales—without intermediaries—and commercialisation at any time of the year. Financial Incentives are essential for the formation and survival of groups in the market, as the activity itself maintains itself and generates profit over the years.

Social Incentives are also achieved in Condominiums, by establishing Warehouses unity among producers through collective action that reflects interpersonal skills, knowledge exchange, technical and professional growth, job creation, and learning. Thus, personal social and psychological characteristics, such as respect and friendship, encourage individuals to organise themselves in groups. In smaller groups, social incentives and ‘social pressure’ are more easily achieved and efficient, favouring the Warehouse Condominiums.

Furthermore, small groups have more advantages over large groups and are more efficient and effective. Social Incentives work best, and the collective benefit is achieved more efficiently, as claimed by Olson [

37]. In addition, small groups have fewer opinions and thus differ less, are more easily controlled and organised, and make decision making more agile and easier.

Furthermore, individual actions in smaller groups are better recognised. Individual efforts will influence the group’s final results in small groups more so than in large groups, and there are no free-riders. Thus, in small groups, economic and social objectives, control and agility of actions, promotion of individual interests, cohesion and efficiency, and the results are more satisfactory than in large groups. It is worth mentioning that there may be competition in the market between small and large groups. These are beneficial for the organisation to be efficient, effective and to promote improvements.

Regarding economic determinants, financial gain is a major benefit, the product’s commercialization—direct sale and superior profitability—is also a considerable benefit, as is the addition of value, and equity in the form of a warehouse. The logistical constraints provide logistical gains offered by the lack of lines, less flow, and proximity of the storage unit with the rural property. Social conditions are exemplified in the unity of rural producers in creating and developing collective action, exchanging information, personal maturation, and strengthening activity and freedom with the product’s sale.

Finally, the model concerns small and medium rural producers, and places with logistical bottlenecks and storage deficits. Rural producers who wish to enjoy the advantages of an association (of collective actions), as well as storage itself, are also targets. There is little knowledge about the Condominium model outside Palotina, Parana, Brazil. The model is generally not known of throughout the country and by Government and Brazilian agribusiness stakeholders.

Rural collective action has recently expanded, mainly in the country’s Southern Region, tackling salient issues associated with farming.

In this study, neither quantitative analyses nor statistical programs were used, which act as limitations of this study. Thus, we suggest it for future studies. It is also worth noting that considering that the study has a qualitative approach, it was not intended to produce generalised results. So, we suggest that future studies conduct a comprehensive survey across the country to identify if there are condominiums of rural warehouses in other Brazilian regions and other countries, by using a quantitative approach.

The selection of the study participants can also be recognised as a limitation because it occurred considering the criteria of representativeness, accessibility and convenience, and we interviewed the managers identified using documental analysis, mainly across the Internet and in reports of Brazilian Associations and the report of the pioneer project supported by FAP-DF, Brasilia, Brazil. We suggest that future studies consider other methods to select participants, such as the snowball sampling method in the case of qualitative studies, or quantitative sampling calculations in the case of quantitative studies.

Furthermore, the study has limitations associated with the size of the studied group of rural grain producers. However, there are few collectives of this type in the Southern Region of Brazil. In this way, we managed to analyse production and organisation experiences that represent the recent phenomenon, although limited by the chosen sample. There is a restriction on the extrapolation of results to other Brazilian contexts due to the sample size, the exploratory nature of the research and the particularities of each region in Brazil.

For future studies, we suggest: (i) analysing and discussing the Condominiums of the Rural Warehouses model under the focus of Transaction Costs Theory; (ii) conducting a technical analysis and economic feasibility studies for Silage and Solar Condominiums; (iii) developing a methodology for measuring the cost (value) of the storage quota, considering the possibility of a partner leaving the model, selling the quota or family succession; (iv) measuring the reduction in logistics costs using the Rural Warehouse Condominium model; (v) measuring agricultural marketing margins through Rural Warehouse Condominiums; and (vi) to apply mathematical models to determine the conditions of Brazilian rural collective actions.