How Safe Is Ginger Rhizome for Decreasing Nausea and Vomiting in Women during Early Pregnancy?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Generality

2.1. Zingiber Officinale Roscoe

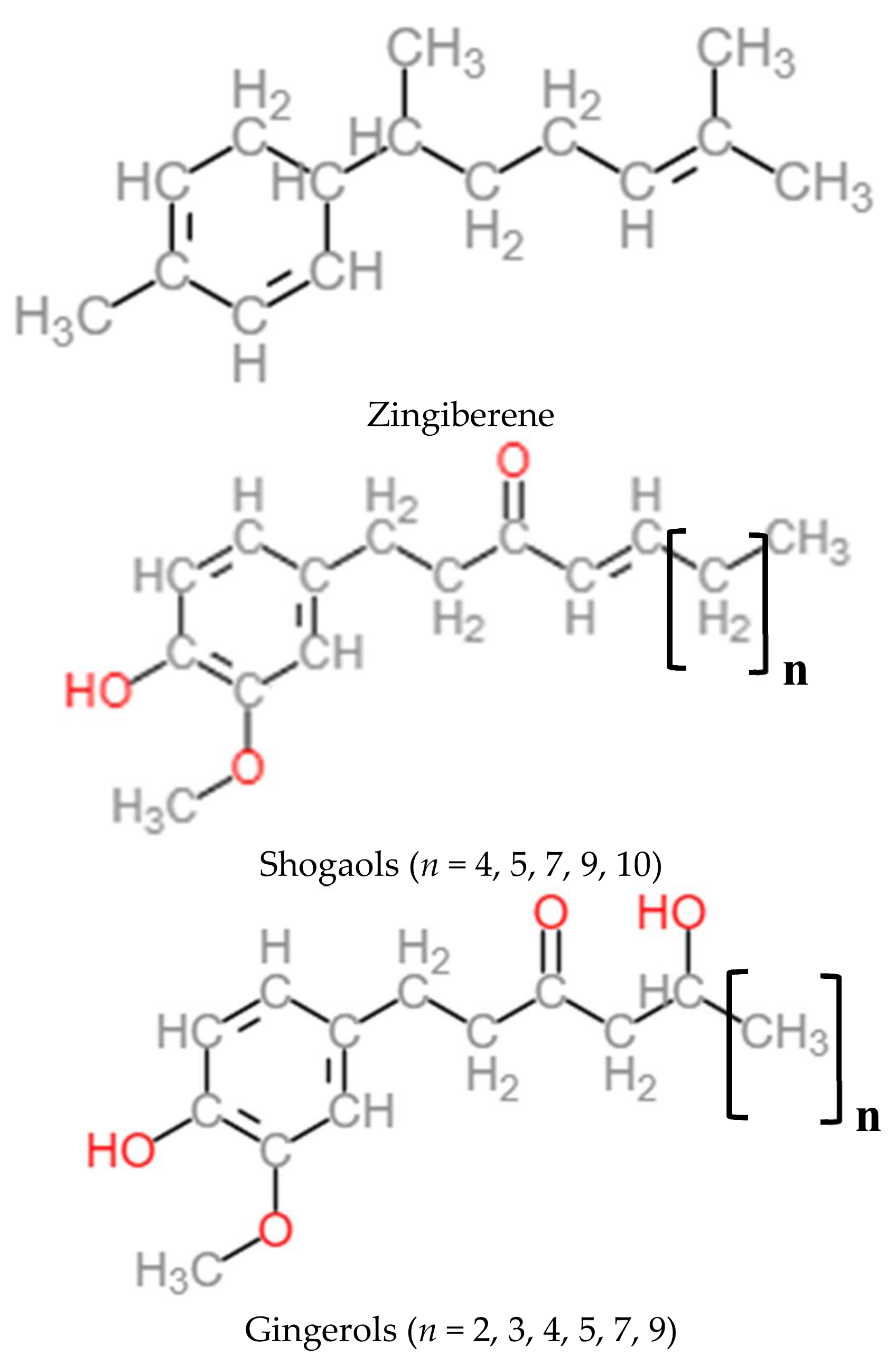

2.2. Nutritional Composition and Chemical Composition

2.3. Ginger Consumption

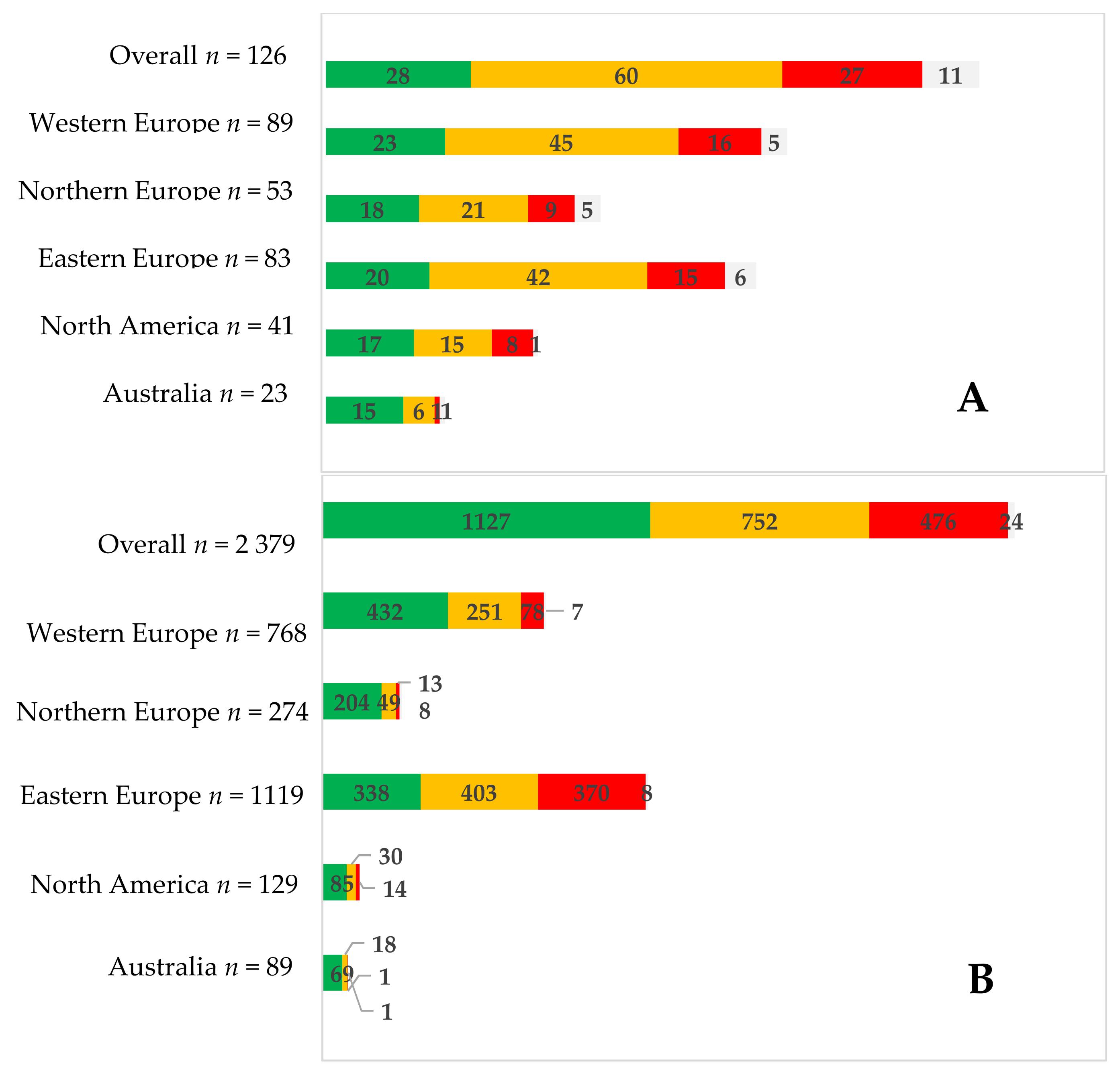

2.4. Women’s Perception of Ginger

3. Non-Clinical Data

3.1. Cytotoxicity

3.2. Genotoxicity/Mutagenicity

3.3. Acute/Subacute Toxicity (Repeated Dose Toxicity)

3.4. Reproductive Toxicity

4. General Population Safety Data

4.1 Pharmacokinetic Data

5. Pregnant Women Data

5.1. Safety Data

5.2. Efficacy

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T&CM | traditional & complementary medicine |

| CAM | complementary and alternative medicine |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| INCA | Étude individuelle nationale des consommations alimentaires |

| ANSES | Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail (France) |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| EU | European Union |

| USA | United States of America |

| RCT | randomized clinical trial |

| EC | European Commission |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| NVP | nausea and vomiting of pregnancy |

| BW | Body Weight |

| ca. | circa |

| HMPC | Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products |

References

- Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS). Stratégie de L’oms Pour la Médecine Traditionnelle Pour 2014–2023; Organisation mondiale de la santé: Genève, Suisse, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parlement Européen et Conseil de l’Europe. Directive 2002/46/ce du Parlement Européen et du Conseil du 10 Juin 2002 Relative au Rapprochement des Législations des Etats Membres Concernant les Compléments Alimentaires. 2002. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000337464&dateTexte=20090923 (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific report of EFSA—Compendium of botanicals reported to contain naturally occuring substances of possible concern for human health when used in food and food supplements. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2663. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère Croate [MINISTARSTVO ZDRAVLJA]. Liste positive vitamines, minéraux, plantes, substances à but physiologiques [pravilnik o tvarima koje se mogu dodavati hrani i koristiti u proizvodnji hrane te tvarima čije je korištenje u hrani zabranjeno ili ograničeno]. Off. J. 2013, 160, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Etat Français. Arrêté du 24 Juin 2014 Etablissant la Liste des Plantes, Autres que les Champignons, Autorisées dans les Compléments Alimentaires et les Conditions de Leur Emploi. 2014. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000029254516&categorieLien=id (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Etat Belge; Etat Français; Etat Italien. Liste Belfrit—Harmonisation de L’emploi des Plantes dans les Compléments Alimentaires au sein D’un Espace Européen: Belgique, France, Italie. 2014. Available online: https://www.economie.gouv.fr/dgccrf/projet-belfrit-cooperation-reussie-au-sein-lunion-europeenne (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Etat Hongrois. Az oéti Szakértői Testülete Altal Etrend-Kiegészítőkben Alkalmazásra nem Javasolt Növények [Plantes Pour une Utilisation Dans les Compléments Alimentaires ne sont pas Recommandés par L’oéti Body Expert]. 2013. Available online: https://anzdoc.com/az-oeti-szakerti-testlete-altal-etrend-kiegeszitkben-alkalma.html (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Eardley, S.; Bishop, F.L.; Prescott, P.; Cardini, F.; Brinkhaus, B.; Santos-Rey, K.; Vas, J.; von Ammon, K.; Hegyi, G.; Dragan, S.; et al. A systematic literature review of complementary and alternative medicine prevalence in eu. Forsch. Komplementmed. 2012, 19 (Suppl. 2), 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire Alimentation, de L’alimentation, de L’environnement et du Travail (ANSES). Étude Individuelle Nationale des Consommations Alimentaires 3 (inca 3). 2017. Available online: https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/etude-inca-3-pr%C3%A9sentation (accessed on 29 November 2017).

- De Ridder, K.; Bel, S.; Brocatus, L.; Lebacq, T.; Ost, C.; Teppers, E. Enquête de consommation alimentaire 2014-2015; Numéro de dépôt: D/2016/2505/51 Référence Interne: PHS Report 2016-042; Institut Scientifique de Santé Publique: Bruxelles, Belgique, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, O.A.; Lindsay, K.L.; McCarthy, M.; McGloin, A.F.; Kennelly, M.; Scully, H.A.; McAuliffe, F.M. Influences on the food choices and physical activity behaviours of overweight and obese pregnant women: A qualitative study. Midwifery 2017, 47, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skeie, G.; Braaten, T.; Hjartaker, A.; Lentjes, M.; Amiano, P.; Jakszyn, P.; Pala, V.; Palanca, A.; Niekerk, E.M.; Verhagen, H.; et al. Use of dietary supplements in the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition calibration study. Eur J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63 (Suppl. 4), S226–S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birdee, G.S.; Kemper, K.J.; Rothman, R.; Gardiner, P. Use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy and the postpartum period: An analysis of the national health interview survey. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014, 23, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, L.; Wright, D.; Haavik, S.; Nordeng, H. Safety and efficacy of herbal remedies in obstetrics--review and clinical implications. Midwifery 2011, 27, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frawley, J.; Adams, J.; Sibbritt, D.; Steel, A.; Broom, A.; Gallois, C. Prevalence and determinants of complementary and alternative medicine use during pregnancy: Results from a nationally representative sample of australian pregnant women. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 53, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings-Tolsma, M.; Vincent, D. Decision-making for use of complementary and alternative therapies by pregnant women and nurse midwives during pregnancy: An exploratory qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2013, 5, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowokere, A.; Olajide, O. Women’s perception of safety and utilization of herbal remedies during pregnancy in a local government area in nigeria. Clin. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.A.; Lupattelli, A.; Koren, G.; Nordeng, H. Safety classification of herbal medicines used in pregnancy in a multinational study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallivalappila, A.R.; Stewart, D.; Shetty, A.; Pande, B.; Singh, R.; McLay, J.S. Complementary and alternative medicine use during early pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 181, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D.; Pallivalappila, A.R.; Shetty, A.; Pande, B.; McLay, J.S. Healthcare professional views and experiences of complementary and alternative therapies in obstetric practice in north east scotland: A prospective questionnaire survey. BJOG 2014, 121, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Hwang, J.H.; Choi, S.; Han, D. Safety classification of herbal medicines used among pregnant women in asian countries: A systematic review. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CBI Market Intelligence; The Ministry of Foreign Affairs. CBI Product Factsheet: Dried Ginger in Europe. Available online: www.cbi.eu/market-information (accessed on 3 November 2017).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Who Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants Volume 1; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, P. British Herbal Compendium. In A Handbook of Scientific Information on Widely Used Plant Drugs; British Herbal Medicine Association: Bournemouth, UK, 1992; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP). Escop Monographs: The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products, 2nd ed.; European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy: Stuttgart, Germany, 2009; ISBN 9783131294210. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA); Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Community Herbal Monograph on Zingiber Officinale Roscoe, Rhizoma; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2012.

- Khan, S.; Pandotra, P.; Qazi, A.; Lone, S.; Muzafar, M.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, S. Medicinal and nutritional qualities of zingiber officinale. In Fruits, Vegetables, and Herbs; Watson, R.R., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 525–550. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper, K. Ginger (zingiber officinale); Longwood Herbal Task Force and the Center for Holistic Pediatric Education and Research. Longwood Herbal Task Force. 1999. Available online: http://www.mcp.edu/herbal/default.htm (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Dhanik, J.; Arya, N.; Nand, V. A review on zingiber officinale. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 6, 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA); Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Assessment Report on Zingiber Officinale Roscoe, Rhizome; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2012.

- Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire Alimentation, de L’alimentation, de L’environnement et du Travail (ANSES). Ciqual, Table de Composition Nutritionnelle des Aliments. Available online: https://ciqual.anses.fr/#/aliments/11006/gingembre-poudre (accessed on 6 November 2017).

- Jolad, S.D.; Lantz, R.C.; Solyom, A.M.; Chen, G.J.; Bates, R.B.; Timmermann, B.N. Fresh organically grown ginger (zingiber officinale): Composition and effects on lps-induced pge2 production. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 1937–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolad, S.D.; Lantz, R.C.; Chen, G.J.; Bates, R.B.; Timmermann, B.N. Commercially processed dry ginger (zingiber officinale): Composition and effects on lps-stimulated pge2 production. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 1614–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, B.H.; Blunden, G.; Tanira, M.O.; Nemmar, A. Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (zingiber officinale roscoe): A review of recent research. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Varoni, E.M.; Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Matthews, K.R.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Kobarfard, F.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Mnayer, D.; Zakaria, Z.A.; et al. Plants of the genus zingiber as a source of bioactive phytochemicals: From tradition to pharmacy. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrahari, P.; Panda, P.; Verma, N.; Khan, W.; Darbari, S. A brief study on zingiber officinale-a review. J. Drug Discov. Ther. 2015, 3, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, I.; McCrea, R.L.; Lupattelli, A.; Nordeng, H. Women’s perception of risks of adverse fetal pregnancy outcomes: A large-scale multinational survey. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plengsuriyakarn, T.; Viyanant, V.; Eursitthichai, V.; Tesana, S.; Chaijaroenkul, W.; Itharat, A.; Na-Bangchang, K. Cytotoxicity, toxicity, and anticancer activity of zingiber officinale roscoe against cholangiocarcinoma. Asian J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 4597–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harliansyah; Murad, N.; Ngah, W.; Yusof, A. Antiproliferative, antixoidant and apoptosis effects of zingiber officinale and 6-gingerol on hepg2 cells. Asian J. Biochem. 2007, 6, 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Unnikrishnan, M.C.; Kuttan, R. Cytotoxicity of extracts of spices to cultured cells. Nutr. Cancer 1988, 11, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abudayyak, M.; Ozdemir Nath, E.; Ozhan, G. Toxic potentials of ten herbs commonly used for aphrodisiac effect in turkey. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 45, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaeoung, S.; Plubrukarn, A.; Keawpradub, N. Cytotoxic and free radical scavenging activities of zingiberaceous rhizomes. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2005, 27, 799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Q.; Ma, J.; Cai, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z. Cytotoxic and apoptotic activities of diarylheptanoids and gingerol-related compounds from the rhizome of chinese ginger. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 102, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Zhong, L.; Jiang, L.; Geng, C.; Cao, J.; Sun, X.; Ma, Y. Genotoxic effect of 6-gingerol on human hepatoma g2 cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 185, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Park, H.; Yang, J.; Shin, T.; Kim, Y.; Baek, N.; Kim, S.; Choi, S.; Kwon, B.; et al. Cytotoxic components from the dried rhizomes of zingiber officinale roscoe. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008, 31, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Tao, Q.; Wu, X.; Dou, H.; Spencer, S.; Mang, C.; Xu, L.; Sun, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Cytotoxic, cytoprotective and antioxidant effects of isolated phenolic compounds from fresh ginger. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 568–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zick, S.M.; Djuric, Z.; Ruffin, M.T.; Litzinger, A.J.; Normolle, D.P.; Alrawi, S.; Feng, M.R.; Brenner, D.E. Pharmacokinetics of 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, 10-gingerol, and 6-shogaol and conjugate metabolites in healthy human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2008, 17, 1930–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zick, S.; Li, X.; Zou, P.; Wright, B.; Sun, D. Examination of the pharmacokinetics of active ingredients of ginger in humans. AAPS J. 2011, 13, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soudamini, K.K.; Unnikrishnan, M.C.; Sukumaran, K.; Kuttan, R. Mutagenicity and anti-mutagenicity of selected spices. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995, 39, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nagabhushan, M.; Amonkar, A.J.; Bhide, S.V. Mutagenicity of gingerol and shogaol and antimutagenicity of zingerone in salmonella/microsome assay. Cancer Lett. 1987, 36, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIrmala, K.; Prasanna Krishna, T.; Polasa, K. In vivo antimutagenic potential of ginger on formation and excretion of urinary mutagens in rats. Int. J. Cancer Res. 2007, 3, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, X.; Peng, G.; Suzuki, T.; Yang, Q.; Yamahara, J.; Li, Y. A 35-day gavage safety assessment of ginger in rats. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 54, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Z.; Sharmaa, P. Attenuation of high-fat diet induced body weight gain, adiposity and biochemical anomalies after chronic administration of ginger (zingiber officinale) in wistar rats. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 7, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Zingiberis rhizome. In Escop Monographs; Stuttgart, T.P., Ed.; European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 547–553. [Google Scholar]

- Weidner, M.; Sigwart, K. Investigation of the teratogenic potential of a zingiber officinale extract in the rat. Reprod. Toxicol. 2001, 15, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, M.; Chen, Y.D.; Saito, K.; Kano, Y. Cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitory component from zingiber officinale roscoe. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1993, 41, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeena, K.; Liju, V.B.; Kuttan, R. A preliminary 13-week oral toxicity study of ginger oil in male and female wistar rats. Int. J. Toxicol. 2011, 30, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojewole, J.A. Analgesic, antiinflammatory and hypoglycaemic effects of ethanol extract of zingiber officinale (roscoe) rhizomes (zingiberaceae) in mice and rats. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suekawa, M.; Ishige, A.; Yuasa, K.; Sudo, K.; Aburada, M.; Hosoya, E. Pharmacological studies on ginger. I. Pharmacological actions of pungent constitutents, (6)-gingerol and (6)-shogaol. J. Pharmacobiodyn. 1984, 7, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Ye, D.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, Y. Effect of dry ginger and roasted ginger on experimental gastric ulcers in rats. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 1990, 15, 278–280, 317–318. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J.M. Effect of ginger tea on the fetal development of sprague-dawley rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 2000, 14, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukandar, E.; Qowiyah, A.; Purnamasari, R. Teratogenicity study of combination of ginger rhizome extract and noni fruit extract in wistar rat. Indones. J. Pharm. 2009, 20, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Rasmussen, W.; Kjaer, S.K.; Dahl, C.; Asping, U. Ginger treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1991, 38, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrubasik, S.; Pittler, M.H.; Roufogalis, B.D. Zingiberis rhizoma: A comprehensive review on the ginger effect and efficacy profiles. Phytomedicine 2005, 12, 684–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, O.; Kranke, P.; Geldner, G.; Wulf, H.; Eberhart, L.H. Is ginger a clinically relevant antiemetic? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Res. Complement. Nat. Class. Med. 2005, 12, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haniadka, R.; Saldanha, E.; Sunita, V.; Palatty, P.L.; Fayad, R.; Baliga, M.S. A review of the gastroprotective effects of ginger (zingiber officinale roscoe). Food Funct. 2013, 4, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viljoen, E.; Visser, J.; Koen, N.; Musekiwa, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, W.; McKavanagh, D.; McCarthy, A.L.; Bird, R.; Ried, K.; Chan, A.; Isenring, L. The effect of ginger (zingiber officinale) on platelet aggregation: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141119. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Q.; Guo, X.; Li, S.; Li, R.; Chu, D.; Ma, Y. Evaluation of daily ginger consumption for the prevention of chronic diseases in adults: A cross-sectional study. Nutrition 2017, 36, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifzadeh, F.; Kashanian, M.; Koohpayehzadeh, J.; Rezaian, F.; Sheikhansari, N.; Eshraghi, N. A comparison between the effects of ginger, pyridoxine (vitamin b6) and placebo for the treatment of the first trimester nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (nvp). J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portnoi, G.; Chng, L.A.; Karimi-Tabesh, L.; Koren, G.; Tan, M.P.; Einarson, A. Prospective comparative study of the safety and effectiveness of ginger for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 189, 1374–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, K.; Nordeng, H.; Holst, L. Safety of ginger use in pregnancy: Results from a large population-based cohort study. Eur J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 69, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.S.; Han, J.Y.; Ahn, H.K.; Lee, S.W.; Koong, M.K.; Velazquez-Armenta, E.Y.; Nava-Ocampo, A.A. Assessment of fetal and neonatal outcomes in the offspring of women who had been treated with dried ginger (zingiberis rhizoma siccus) for a variety of illnesses during pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 35, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paritakul, P.; Ruangrongmorakot, K.; Laosooksathit, W.; Suksamarnwong, M.; Puapornpong, P. The effect of ginger on breast milk volume in the early postpartum period: A randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Breastfeed. Med. 2016, 11, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongrojpaw, D.; Somprasit, C.; Chanthasenanont, A. A randomized comparison of ginger and dimenhydrinate in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. J. Med. Assoc. Thai 2007, 90, 1703–1709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saberi, F.; Sadat, Z.; Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi, M.; Taebi, M. Acupressure and ginger to relieve nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: A randomized study. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2013, 15, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberi, F.; Sadat, Z.; Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi, M.; Taebi, M. Effect of ginger on relieving nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2014, 3, e11841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, A.; Chez, R.A. Ginger syrup as an antiemetic in early pregnancy. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2002, 8, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.; Crowther, C.; Willson, K.; Hotham, N.; McMillian, V. A randomized controlled trial of ginger to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 103, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vutyavanich, T.; Kraisarin, T.; Ruangsri, R. Ginger for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: Randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chittumma, P.; Kaewkiattikun, K.; Wiriyasiriwach, B. Comparison of the effectiveness of ginger and vitamin b6 for treatment of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2007, 90, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozgoli, G.; Goli, M.; Simbar, M. Effects of ginger capsules on pregnancy, nausea, and vomiting. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensiyeh, J.; Sakineh, M.A. Comparing ginger and vitamin b6 for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: A randomised controlled trial. Midwifery 2009, 25, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadbeigi, R.; Shahgeibi, S.; Soufizadeh, N.; Rezaiie, M.; Farhadifar, F. Comparing the effects of ginger and metoclopramide on the treatment of pregnancy nausea. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 14, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Willetts, K.E.; Ekangaki, A.; Eden, J.A. Effect of a ginger extract on pregnancy-induced nausea: A randomised controlled trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2003, 43, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basirat, Z.; Moghadamnia, A.; Kashifard, M.; Sharifi-Ravazi, A. The effect of ginger biscuit on nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Acta Medica Iran. 2009, 47, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Boltman-Binkowski, H. A systematic review: Are herbal and homeopathic remedies used during pregnancy safe? Curationis 2016, 39, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLay, J.S.; Izzati, N.; Pallivalapila, A.R.; Shetty, A.; Pande, B.; Rore, C.; Al Hail, M.; Stewart, D. Pregnancy, prescription medicines and the potential risk of herb-drug interactions: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lete, I.; Allue, J. The effectiveness of ginger in the prevention of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy and chemotherapy. Integr. Med. Insights 2016, 11, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Leach, M.; Bradley, H. The effectiveness and safety of ginger for pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting: A systematic review. Women Birth 2013, 26, e26–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, M.; Corbin, R.; Leung, L. Effects of ginger for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2014, 27, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, K.; Rowe, H.; Azzam, H.; Lane, C.A. The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2016, 38, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwertner, H.A.; Rios, D.C.; Pascoe, J.E. Variation in concentration and labeling of ginger root 39 dietary supplements. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukkavilli, R.; Yang, C.; Tanwar, R.S.; Saxena, R.; Gundala, S.R.; Zhang, Y.; Ghareeb, A.; Floyd, S.D.; Vangala, S.; Kuo, W.W.; et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlations in the development of ginger extract as an anticancer agent. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA); Committee on herbal medicinal products (HMPC). Opinion of the HPMC on a Community Herbal Monograph on Zingiber Officinale Roscoe, Rhizome; EMA/HPMC/216956/2012; European Medicines Agency (EMA): London, UK, 2012.

- Shawahna, R.; Taha, A. Which potential harms and benefits of using ginger in the management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy should be addressed? A consensual study among pregnant women and gynecologists. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Men (%) | Women (%) |

|---|---|---|

| France | 17–21.6 | 26.3–28.5 |

| Belgium | 11–14 | 22.5–30 |

| Australia | 34.9 | 50.3 |

| USA | 45 | 58 |

| Greece | 2 | 6.7 |

| Spain | 5.9 | 12.1 |

| Italy | 6.8 | 12.6 |

| Germany | 20.7 | 27 |

| The Netherlands | 16 | 32.1 |

| UK | 36.3 | 47.5 |

| Denmark | 51 | 65.8 |

| Sweden | 30.5 | 42.4 |

| Country | Composition | Daily Dose | Claims |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | Cellulose; standardized ginger extract 50 mg with 10% gingerols (equal to 500 mg of powder); calcium phosphate; silicon dioxide, magnesium stearate; hypromellose, titanium dioxide; talc; glycerol | 2/day for pregnant women | Helps you regain optimal digestive balance in the following situations: - in case of overeating - in case of unusual diets - when agitated or on trips - too much stress Can be used in pregnant women who wish to return to digestive well-being during pregnancy |

| Ginger bio extract (6 × concentrated) 200 mg | 1/day | Digestive comfort | |

| 500 mg of ginger rhizome powder and 5 mg of ginger rhizome extract per caps | 1/day | Sexual fatigue; nausea in pregnant women; travel sickness | |

| Ginger rhizome extract: 67 mg, eq. to 1 g of ginger rhizome, magnesium carbonate, vitamin B6 | 1/day | Ginger contributes to the normal functioning of the stomach in case of early pregnancy (Claim under consideration (EFSA)) Magnesium contributes to a reduction of tiredness and fatigue Vitamin B6 contributes to the regulation of hormonal activity | |

| France | Organic ginger rhizome powder: 250 mg | 4/day | Nausea in pregnant women |

| Ginger rhizome powder (Zingiber officinale R): 365 mg/hard caps | 4/day | Lower bowel contractions and digestive acids; prevent motion-induced nausea and vomiting | |

| Organic ginger rhizome extract (Zingiber officinale R): 200 mg | 2/day | Ginger contributes to the normal functioning of the stomach in case of early pregnancy | |

| Organic ginger rhizome extract (Zingiber officinale R): 200 mg | 5/day | Travel sickness | |

| Zingiber officinalis R (roots): 230 mg. | 6/day | Helps to support the digestion/contributes to the normal function of intestinal tract Travel sickness Joint mobility Libido in men | |

| Sorbitol, rhizome ginger extract (Zingiber officinale R), natural orange flavor, sodium starch glycolate, microcrystalline cellulose, natural lemon flavor, magnesium stearate, silica, sucralose. | 2/day | - | |

| Ginger, lemon, B6, magnesium, iron, B9 | 5 biscuits/day | - | |

| B6, folates, cocoa, strawberry pulp, ginger | 1/day | - | |

| Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum J. Presl), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.), lemon (Citrus limon (L.) Burm f.), Tumeric (Curcuma longa L.), hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.), liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L), natural lemon flavor and natural vanilla flavor | 1–3 sachets /day | - | |

| Cellulose, silicon dioxide, magnesium stearate, standardized ginger extract (Zingiber officinale R) 50 mg; HPMC, titanium dioxide, talc, copper complexes of chlorophyllins | Pregnant women: 2/day Children from 6 to 11 years old: 1 to 4/day Adults and Children >12 years old: 2 to 8/day | Nausea in pregnant women; travel sickness Ginger contributes to the normal functioning of the stomach (Claim under consideration (EFSA)) | |

| Cellulose, standardized ginger extract (10% of gingerols) 50 mg eq. to 500 mg of ginger powder; calcium phosphate; silicon dioxide; magnesium stearate; HMPC; titanium dioxide, talc, glycerol. | 2/day for pregnant women | Helps to support the digestion/contributes to the normal function of intestinal tract/contributes to the normal functioning of the stomach in case of early pregnancy or travel sickness For adults and children aged 12 years and above | |

| Microcrystalline cellulose, standardized ginger extract 50 mg, eq. to 500 mg of rhizome powder, silicon dioxide, fatty acid magnesium salts, hypromellose, titanium dioxide, talc, glycerol | 2 hard caps 3 times per day | Helps to support the digestion Contributes to decrease discomforts in case of travel nausea, pregnant women nausea, or chemotherapy | |

| Bach flowers, essential oils, and plant extracts | 5 sprays if nauseous | Quick-acting oral spray against discomfort, apprehension and transport. | |

| Ginger root extract (160 mg of extract, 16 mg of gingerols); lemon balm extract (100 mg) | 4/day | Stomach; antiemetic; pregnant women | |

| Italy | Standardized root extract: 300 mg (5% gingerols) Whole root pulverized: 1500 mg | 2/day | Regulate the gastro-intestinal motility and gas elimination of in case of nausea Promotes joint function and counteracts the localized states of tension Counter menstrual cycle disorders |

| Hydro-alcoholic standardized ginger extract (5% of gingerols) | 2/day | Reducing nausea, gas, bloating and intestinal spasms | |

| Poland | Ginger rhizome extract 75 mg (eq. to 300 mg of powder); Vitamin B6: 0.5 mg | 3/day | Adults and children poorly tolerating travel by vehicles and craft: cars, buses, trains, ships, planes |

| UK | Ginger extract 55 mg eq. to 1.1 g of root powder | 1/day | Helps calm a queasy stomach; an excellent stomach soother; excellent travel companion |

| Ginger extract 120 mg eq. to 14 g of root powder (24 mg of gingerols) (120:1 extract) | 1/day | Do not take if pregnant or breastfeeding | |

| Ginger extract 138 mg eq. to 550 mg | 2/day | - | |

| Ginger root 500 mg | 2/day | - | |

| Ginger root extract (Zingiber officinale R) 500 mg, vitamin B6 25 mg, vitamin D 200 IU, calcium (carbonate and lactate) 240 mg, red raspberry leaf 25 mg, mint leaf 25 mg Citrus aurantifolia 10 mg Contains no artificial colors or flavors. | 2/day | - | |

| US | Ginger root powder | 2/day | - |

| Ginger root powder | 2/day | May soothe an upset stomach and support digestion Promotes a healthy inflammation response May help reduce nausea, vomiting and dizziness | |

| Ginger root powder | 2/day | Helps calm a queasy tummy an excellent stomach soother Excellent travel companion |

| USDA (National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference) | ANSES (Table Ciqual 2016 Composition Nutritionnelle des Aliments) | DTU (Fødevaredatabanken Version 7.01) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginger type | Ginger Root, Raw | Ginger, Powder | Ginger Root, Raw |

| Phosphorus (mg/100 g) | 34 | 168 | 34 |

| Magnesium (mg/100 g) | 43 | 214 | 43 |

| Potassium (mg/100 g) | 415 | 1 320 | 415 |

| Manganese (mg/100 g) | - | 33.3 | 0.229 |

| Zinc (mg/100 g) | 0.34 | 3.64 | 0.34 |

| Iron (mg/100 g) | 0.60 | 19.8 | 0.60 |

| Calcium (mg/100 g) | 16 | 114 | 16 |

| Niacin (mg/100 g) | 0.750 | 9.62 | 0.950 |

| Folate (μg/100 g) | 11 | 13 | 11 |

| Australia | Eastern Europe | Eastern Europe | Western Europe | North America | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cranberries | |||||

| Ginger | |||||

| Eggs | |||||

| Paracetamol | |||||

| OTC (against nausea | |||||

| Antibiotics | |||||

| Swine flu vaccine | |||||

| Blue-veined cheese | |||||

| Dental X-ray | |||||

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Alcohol (1st trimester) | |||||

| Smoking | |||||

| Thalidomide |

| Ginger, Ginger Extracts, or Related Compounds | Cell Line | IC50 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol extract of ginger | CL-6–Calcein assay | 10.95 µg/mL | Plengsuriyakarn et al., 2012 [38] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | CL-6–Hoechst 33342 assay | 53.13 µg/mL | Plengsuriyakarn et al., 2012 [38] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | HepG2–Calcein assay | 71.89 µg/mL | Plengsuriyakarn et al., 2012 [38] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | HepG2–Hoechst 33342 assay | 92.88 µg/mL | Plengsuriyakarn et al., 2012 [38] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | HepG2 | 358.71 µg/mL | Harliansyah et al., 2007 [39] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | HRE–Calcein assay | 198.15 µg/mL | Plengsuriyakarn et al., 2012 [38] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | HRE–Hoechst 33342 assay | 245.91 µg/mL | Plengsuriyakarn et al., 2012 [38] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | Hamster ovary | 245 µg/mL | Unnikrishnan et al., 1988 [40] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | Vero cells | 120 µg/mL | Unnikrishnan et al., 1988 [40] |

| Ethanol extract of ginger | Dalton’s Lymphoma Ascites | 200 µg/mL | Unnikrishnan et al., 1988 [40] |

| Aqueous extract of ginger | Dalton’s Lymphoma Ascites | 420 µg/mL | Unnikrishnan et al., 1988 [40] |

| Aqueous extract of ginger | NRK-52E Cells (MTT test) | No cytotoxicity | Abudayyak et al., 2015 [41] |

| Chloroform extract of ginger | NRK-52E Cells (MTT test) | 9.08 mg/mL | Abudayyak et al., 2015 [41] |

| Methanol ginger extract | MCF7 (Breast) | 75 µg/mL | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42] |

| Methanol ginger extract | LS174T (Colon) | 80 µg/mL | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42] |

| Volatile oil of ginger | MCF7 (Breast) | 14.2 µg/mL | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42] |

| Volatile oil of ginger | LS174T (Colon) | 15.9 µg/mL | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42] |

| Related compounds | |||

| Diarylheptanoids and gingerol-related compounds | HL-60 | <50 µmol/L | Wei et al., 2005 [43] |

| 6-gingerol | HepG2 | 431.7 µg/mL | Harliansyah et al., 2007 [39] |

| 6-gingerol | MCF7 (Breast) | 31.6 µg/mL | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42] |

| 6-gingerol | LS174T (Colon) | 30.6 µg/mL | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42] |

| 6-gingerol | HepG2 | 89.58 µg/mL | Yang et al., 2010 [44] |

| 6-shogaol | MCF7 (Breast) | 6 µg/mL | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42] |

| 6-shogaol | LS174T (Colon) | 4.2 µg/mL | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42] |

| Ginger Related-Compounds | IC50 (µg/mL) | Plasma Concentration after 1.5 or 2 g of Ginger (µg/mL) | Ratio IC50/Concentration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-gingerol | 15.72 to 431.7 | 1.69 | 9.3 to 255.4 | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42]; Harliansyah et al., 2007 [39]; Kim et al., 2008 [45]; Zick et al., 2008 [47] |

| 6-shogaol | 1.05 to 6 | 0.0136 to 0.15 | 7 to 441.2 | Zaeoung et al., 2005 [42]; Kim et al., 2008 [45]; Zick et al., 2008 [47]; Yu et al., 2011 [48] |

| 8-gingerol | 8.85 to 12.57 | 0.23 | 38.5 to 54.7 | Kim et al., 2008 [45]; Zick et al., 2008 [47] |

| 10-gingerol | 4.2 to 6.57 | 0.0095 to 0.53 | 7.9 to 691.6 | Kim et al., 2008 [45]; Zick et al., 2008 [47]; Yu et al., 2011 [48] |

| Test Object | Concentration | Results | References | |

| In Vitro | ||||

| Ginger | ||||

| Ames assay | Salmonella typhimurium strains TA 100, TA 98, TA 1535, and TA 1538 with and without activation | 5 to 200 µg/plate | Mutagenic on metabolic activation in strains TA 100 and TA 1535 | Nagabhushan et al., 1987 [50] |

| Ames assay | S. typhimurium TA 100 and TA 1535, with and without activation | 25 and 50 mg/mL | Mutagenic in both TA, at both concentrations | Soudamini et al., 1995 [49] |

| Ames assay | S. typhimurium TA 100 and TA 98, with and without activation | 0.78 to 25 mg/mL | Mutagenic on TA 98 activated cells from 3.13 mg/mL | Abudayyak et al., 2015 [41] |

| 6-gingerol | ||||

| Comet assay | HepG2 | 0 to 80 µmol/L | DNA strand breaks from 5.89 mg/mL (20 µmol/L) | Yang et al., 2010 [44] |

| Ames assay | Salmonella typhimurium strains TA 100, TA 98, TA 1535, and TA 1538 with and without activation | 5 to 200 µg/plate | Mutagenic on metabolic activation in strains TA 100 and TA 1535 | Nagabhushan et al., 1987 [50] |

| Shogaol | ||||

| Ames assay | Salmonella typhimurium strains TA 100, TA 98, TA 1535, and TA 1538 with and without activation | 5 to 200 µg/plate | Mutagenic on metabolic activation in strains TA 100 and TA 1535 | Nagabhushan et al., 1987 [50] |

| Zingerone | ||||

| Ames assay | Salmonella typhimurium strains TA 100, TA 98, TA 1535, and TA 1538 with and without activation | 5 to 200 µg/plate | No mutagenic effect | Nagabhushan et al., 1987 [50] |

| Administration | Species | Oral LD50 | References | |

| Ginger dried rhizome powder | ||||

| Ginger powder | per os | Rats | No mortality | Rong et al., 2009 [52] |

| Ginger dried rhizomes extracts | ||||

| Ginger dried rhizomes ethanol extract | intraperitoneal | Mice | 1551 ± 75 mg/kg | Ojewole et al., 2006 [58] |

| Ginger dried rhizomes ethanol extract | per os | Hamsters | No mortality | Plengsuriyakarn et al., 2012 [38] |

| Patented standardized ethanol extract of dried rhizomes of ginger (EV.EXT 33) | per os | Pregnant rats | No mortality | Weidner et al., 2001 [55] |

| Freeze-dried ginger powder | per os | Rats | No mortality | Malik et al., 2011 [53] |

| Dry ginger decoction | per os | Rats: Gastric ulcer models | 250 g/kg | Wu et al., 1990 [60] |

| Roasted ginger decoction | per os | Rats: Gastric ulcer models | 170.6 g/kg | Wu et al., 1990 [60] |

| Ginger dried rhizomes ethanol extract | Mice | No mortality at 2.5 g/kg | Anonymous, 2003 [54] | |

| Ginger oil | per os | Rabbits | 5 g/kg | Anonymous, 2003 [54] |

| Ginger oil | per os | Rats | No mortality | Jeena et al., 2011 [57] |

| Related compounds | ||||

| (E)-8 beta,17-epoxylabd-12-ene-15,16-dial (ZT) | ||||

| (E)-8 beta,17-epoxylabd-12-ene-15,16-dial (ZT) from ginger | per os (25 mg/kg) | Mice | No mortality | Tanabe et al., 1993 [56] |

| (E)-8 beta,17-epoxylabd-12-ene-15,16-dial (ZT) from ginger | Intra-abdominal (25 mg/kg) | Mice | No mortality | Tanabe et al., 1993 [56] |

| 6-shogaol | ||||

| 6-shogaol | intravenous | Mice | 50.9 mg/kg | Suekawa et al., 1984 [59] |

| 6-shogaol | intraperitoneal | Mice | 109.2 mg/kg | Suekawa et al., 1984 [59] |

| 6-shogaol | per os | Mice | 687 mg/kg | Suekawa et al., 1984 [59] |

| 6-gingerol | ||||

| 6-gingerol | intravenous | Mice | 25.5 mg/kg | Suekawa et al., 1984 [59] |

| 6-gingerol | intraperitoneal | Mice | 58.1 mg/kg | Suekawa et al., 1984 [59] |

| 6-gingerol | per os | Mice | 250 mg/kg | Suekawa et al., 1984 [59] |

| Objective | Population | Number | Treatment | Ginger Definition | Duration | Results | Adverse Events | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To determine the effectiveness of ginger for the treatment of NVP | Women NVP < 17 weeks of gestation | n = 67 35 placebo 32 ginger | 1000 mg/day (4 × 250 mg) of ginger (powder capsules) vs. placebo | Fresh ginger root | 4 days + follow-up visit 7 days later | Significant decrease of nausea in the ginger group vs. placebo group (p = 0.014) Significant decrease of vomiting in the ginger group vs. placebo group (p < 0.001) Follow-up visits:Significant symptom improvement in the ginger group vs. placebo group (p < 0.001) | Headache: - 5 in the placebo group - 6 in the ginger group. Ginger group: - 1 abdominal discomfort - 1 heartburn - 1 diarrhoea for one day Side effects reported as minor. Spontaneous abortions: - 3 in the placebo group - 1 in the ginger group Term delivery: - 91.4% in the placebo group - 96.9% in the ginger group Cesarean deliveries: - 4 in the placebo group - 6 in the ginger group No infants had any congenital anomalies recognized. No significant adverse effect of ginger on pregnancy outcome was reported. | Vutyavanich et al., 2001 [80] |

| To compare the effectiveness of ginger and vitamin B6 for treatment of NVP | Women NVP < 16 weeks of gestation | n = 123 62 vit. B6 61 ginger | 1950 mg/day of ginger (3 × 650 mg) or 75 mg/day of vitamin B6 (3 × 25 mg) | Fresh ginger root | 4 days | Nausea/vomiting: Improvement of nausea vomiting scores in both group from baseline The average score change in the ginger group was better than that of vitamin B6 group (p < 0.05) | Side effects: - 16 in ginger group - 15 in B6 group (NS) Heartburn: - 8 in ginger group - 2 in B6 group Sedation: - 7 in ginger group - 11 in B6 group Arrhythmia: - 1 in ginger group Headache: - 2 in B6 group Side effects were reported to be minor | Chittumma et al., 2007 [81] |

| To determine the effectiveness of ginger for the treatment of NVP | Women NVP < 20 weeks of gestation | n = 67 35 placebo 32 ginger | 1000 mg/day (4 × 250 mg) of ginger (powder capsules) | Ginger root powder (Zintoma, Goldaroo Company, Tehran, Iran) | 4 days | Nausea: Significant improvement in 84% of ginger users vs. 56% in the control group (p < 0.05) Vomiting: Significant improvement in the treated group vs. the control group (p < 0.05) | No complication during the treatment period was reported Reported as a safe remedy to improve the nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. | Ozgoli et al., 2009 [82] |

| To compare the effectiveness of ginger and vitamin B6 for the treatment of NVP | Women with nausea with or without vomiting < 17 weeks of gestation | n = 69 34 vit. B6 35 ginger | 1000 mg/day (2 × 500 mg) of ginger (powder capsules) or 40 mg/day of vitamin B6 (2 × 20 mg) | Fresh ginger root | 4 days + follow-up visit 7 days later | Nausea score: Better score in the ginger group vs. the vitamin group (p = 0.024) Vomiting episodes: No significant difference between the groups Follow-up visits: 82.8% reported an improvement in the ginger group vs. 67.6% in the vitamin group (p = 0.52) | Spontaneous abortions: - 2 in the ginger group - 1 in the B6 group (p > 0.05) Term birth: - 82.9% in the ginger group - 82.4% in the B6 group Caesarean deliveries: - 4 in the ginger group - 6 in the B6 group (p > 0.05) No babies had any congenital anomalies All were discharged in good condition No adverse effects of ginger on pregnancy outcome were reported | Ensiyeh et al., 2009 [83] |

| To compare the effects of ginger on nausea and vomiting caused by pregnancy and compares it with metoclopramide medicine | Women NVP < 20 weeks of gestation | n = 102 34 placebo 34 metoclopramide 34 ginger | 600 mg/day (3 × 200 mg) ginger;30 mg/day (3 × 10 mg) metoclopramide;600 mg/day (3 × 200 mg) placebo | Ginger essence | 5 days | Intensity of nausea: Significant difference in the two supplemented groups (ginger or metoclopramide) vs. placebo (p < 0.05) Not statistically significant between treated groups | - | Mohammadbeigi et al., 2011 [84] |

| To determine if ginger syrup mixed in water is an effective remedy for the relief of NVP | Women with nausea with or without vomiting first trimester | n = 23 10 placebo 13 ginger | 1 g/day (4 × 250 mg) ginger (tablespoon) vs placebo | Ginger including 1 mg pungent compounds from ginger rhizome juice, 1 mg of 20% pungent compounds and 5% zingiberene coming from CO2 supercritical extract of ginger rhizome | 2 weeks | Nausea: 77% improvement in ginger group vs. 20% in placebo group Vomiting: 67% in ginger group stop vomiting at day 6 vs 20% in placebo group | Delivered viable infant at term without major complications Safe option in the treatment of NVP | Keating et al., 2002 [78] |

| To investigate the effect of a ginger extract (EV.EXT35) on the symptoms of morning sickness. | Women with morning sickness < 20 weeks of gestation | n = 9951 placebo48 ginger | 500 mg/day (4 × 125 mg) eq. 6 g/day ginger vs. placebo | EV.EXT35: ginger extract (125 mg eq to 1.5 g of dried ginger) | 4 days | Nausea experience score: - except for day 3, the difference parameter for each day post-baseline, was significantly less than zero Vomiting: - no significant difference between the groups | Spontaneous abortion: - 3 in the ginger group - 1 in the placebo group Intolerance of the treatment: - 4 in the ginger group Worsening of treatment requiring further medical assistance: - 1 in the ginger group - 2 in the placebo group Allergic reaction to treatment: - 1 ginger group No apparent increased risk of fetal abnormalities or low birth weight. | Willetts et al., 2003 [85] |

| To estimate whether the use of ginger to treat nausea or vomiting in pregnancy is equivalent to pyridoxine hydrochloride (vitamin B6) | Women NVP Between 8 and 16 weeks of gestation | n = 235 115 vit. B6 120 ginger | 1.05 g/day ginger (3 × 350 mg) vs. 75 mg/day vitamin B6 (3 × 25 mg) | - | 3 weeks | 53% reported an improvement taking ginger, and 55% reported an improvement with vitamin B6 Ginger was equivalent to vitamin B6 for improving nausea, dry retching, and vomiting | Belching: - ginger (9%) vs. B6 (0%) (p < 0.05) Dry retching after swallowing: - ginger (52%) vs. B6 (56%) Vomiting after ingestion: - ginger (2%) vs. B6 (1%) Burning sensation: - ginger (2%) vs. B6 (2%) Pregnancy outcome: - 272 (93%) gave birth to 278 infants - 12 women with spontaneous abortion (first or second trimester) - 3 women with stillbirth - No differences were found between study groups - 9 babies born with congenital abnormality (3 ginger, 6 B6) (NS) - 6 cases of urogenital disorders - 2 cases of minor gastrointestinal abnormalities -1 case of a minor congenital heart defect | Smith et al., 2004 [79] |

| To examine the evidence for the safety and effectiveness of ginger for NVP | Women NVP Between 7 and 17 weeks of gestation | n = 62 30 placebo 32 ginger | 5 biscuits/day (2.5 g of ginger) vs. placebo | - | 4 days + follow-up visit 7 days later | Nausea scores: - significantly greater in the ginger group vs. in placebo group (p = 0.01) Vomiting episodes: - no significant difference (p = 0.243) No vomiting after 4 days: - 34% in ginger group vs. 18% in placebo group Follow-up visits: - 87.5% ginger group reported improvement vs. 70% in placebo group (p = 0.043) | In ginger group: - 1 dizziness - 1 heartburn The side effects reported as minor. No abnormal pregnancy and delivery outcome occurred. No infants had any congenital abnormalities recognized. All discharged in good condition | Basirat et al., 2009 [86] |

| To compare the breast milk volume during the early postpartum period between women receiving dried ginger capsules with those receiving placebo | Women ≥ 37 weeks gestation | n = 63 33 placebo 30 ginger | 1 g of ginger (500 mg × 2) vs. placebo | Dried ginger powder | 7 days | Breast milk volume: - day 3 ginger group has higher milk volume than the placebo group (p < 0.01) - day 7, the ginger group does not differ from the placebo group Prolactin levels is similar in both groups | No notable side effects | Paritakul et al., 2016 [74] |

| To study the efficacy of ginger and dimenhydrinate in the treatment of NVP | Women NVP < 16 weeks of gestation | n = 170 85 dimenhydrinate 85 ginger | 1 g (500 mg × 2) of ginger vs. 100 mg (50 mg × 2) of dimenhydrinate | - | 1 week | Nausea: - the mean score in day 1-7 decreased in both groups - daily mean scores between both groups were not statistically different Vomiting: - frequency of vomiting times in day 1-7 decreased in both groups - daily mean vomiting times in the dimenhydrinate group in day 1-2 were less than the ginger group (p < 0.05) - after day 3–7 post treatment, the daily mean vomiting times in both groups were not statistically different | Drowsiness: - 5/85 in the ginger group vs. 66/85 in dimenhydrinate group (p < 0.01) Heart burn: - 13/85 in the ginger group vs. 9/85 in dimenhydrinate group (p = 0.403) No other adverse effect was reported in both groups | Pongrojpaw et al., 2007 [75] |

| To study the efficacy of ginger and placebo in hyperemesis gravidarum. | Women hyperemesis gravidarum < 20 weeks of gestation | n = 27 13 lactose 14 ginger | 1 g (250 mg × 4) of ginger vs. placebo | Powdered root | 2 × 4 days 2 days washout | The preference: - ginger treatment period was statistically significant (p = 0.003) Relief of the hyperemesis symptoms: - significantly greater in ginger group vs. placebo (p = 0.035) | One spontaneous abortion, which was not a suspicious high rate of fetal wastage in early pregnancy No side effects were observed All infants were without deformities and discharged in good condition. | Fischer-Rasmussen et al., 1991 [63] |

| To compare the effectiveness of ginger and acupressure in the treatment of NVP | Women NVP < 16 weeks of gestation | n = 143 45 control 48 acupressure | 750 mg (250 mg × 3) of ginger vs. acupressure | - | 7 days - 3 with no intervention - 4 with treatment | Rhodes index scores: - better in the ginger group vs. acupressure and control (p < 0.001) - reduced 49% in ginger group and 29% in acupressure group. - increased up to 0.06% in control group Post hoc test showed significant differences in vomiting, nausea, retching, and total scores between the groups except for vomiting score between acupressure and control groups and for retching score between acupressure and ginger groups | 1 case of heartburn with ginger capsules | Saberi et al., 2013 [76] |

| To determine the effect of ginger to relieve NVP | Women NVP < 16 weeks of gestation | n = 106 36 placebo 33 control 37 ginger | 750 mg (250 mg × 3) of ginger vs. acupressure | - | 7 days - 3 with no intervention - 4 with treatment | Rhodes index scores: - greater in the ginger group vs. placebo and control (p < 0.001) - reduced 48% in ginger group,13% in placebo group and -10% in control group Post hoc test showed significant difference between the groups in reduction of vomiting, nausea, retching and total Rhodes Index scores (p < 0.001) | 1 case of heartburn with ginger capsules | Saberi et al., 2014 [77] |

| To compare the effects of ginger, pyridoxine (vitamin B6), and placebo for the treatment of NVP | Women between 6 and 16 weeks of pregnancy; mild and moderate NVP | n = 77 23 placebo 26 vit. B6 28 ginger | 1 g (500 mg × 2) ginger capsules 80 mg (40 mg × 2) Vit. B6 capsules | - | 4 days | Rhodes index scores: - ginger > placebo (p = 0.039) - Vit. B6 > placebo (p = 0.007) - ginger = Vit. B6 (p = 0.128) Ginger was more effective for - nausea intensity - nausea distress - distress of vomiting | Ginger is effective and safe | Sharifzadeh et al., 2017 [70] |

| Study Type | Objective | Population | Number | Treatment | Ginger Definition | Duration | Results | Adverse Events | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective cohort study (Korean Motherisk Program) | To determine if ginger exposure during pregnancy would increase the risk of adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes | Women Cough and cold preparations (49.7%) Functional gastrointestinal disorders (37.7%) 3 days to 20.7 weeks | 159 306 (control group) | Median dose: 470 mg/day Maximum dose: 7.2 g/day | Dried ginger | Median length: 2 days | Spontaneous abortion: - 7 in the ginger group vs. 17 in the control group (NS) Stillbirths: - 2.7% in the ginger group vs. 0.3% in the control group (NS) NICU admission: - 4.7% in the ginger group vs. 1.7% in the control group (NS) The admission rate was marginally different between cases and controls however, no difference was observed when admission rate was compared with that reported in 2012 at the hospital. They concluded that dried ginger is not a major human teratogen | Choi et al., 2014 [73] | |

| The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study | To evaluate the safety of ginger use during pregnancy on congenital malformations | Women NVP first trimester | n = 68 522 - 1020 (use ginger) - 466 (use ginger during 1st trimester) | - | - | - | Not increase the risk of malformations No significant associations between ginger use risk of: - Stillbirth - Perinatal death - Low birth weight - Preterm birth - Low Apgar score | Heitmann et al., 2013 [72] | |

| Prospective cohort study (The Motherisk Program) | The primary objective: - to examine the safety The secondary objective: - to examine the effectiveness of ginger for NVP | Women first trimester | 187 (ginger group) 187 (comparison group) | Various types of ginger: - Capsules (49%) - Ginger tea - Fresh ginger - Pickled ginger - Ginger cookies - Ginger candy - Inhaled powdered ginger - Ginger crystals - Sugared ginger | - | Minimum 3 days | Ginger effectiveness scores (overall) on 66 women - 3.6 ± 2.4 (SD) Scale range of effectiveness: - 0 => 29 (43.9%) - 2–4 => 19 (28.8%) - 5–7 => 13 (19.7%) - 8–10 => 6 (7.6%) 0 = No effect; 1–4 = mild effect; 5–7 = moderate effect; 8–10 = best effect. | - 3 spontaneous abortions - 2 stillbirths - 1 therapeutic abortion (Down syndrome) 3 major malformations in the ginger group: - ventricular septal defect - lung abnormality - kidney abnormality (pelviectasis) - 1 idiopathic central precocious puberty at 2 years old No significant differences between the groups in terms of live births, spontaneous abortions, stillbirths, therapeutic abortions, birth weight, or gestational age. Eight sets of twins in the ginger group. More babies < 2.5 Kg in the control group | Portnoi et al., 2003 [71] |

| Adverse Effects Identified (No Significance) | References |

|---|---|

| Headache, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, heartburn, spontaneous abortion | Vutyavanich et al., 2001 [80] |

| Sedation, arrhythmia, heartburn | Chitumma et al., 2007 [81] |

| Intolerance, allergic reaction, medical assistance, spontaneous abortion | Willets et al., 2003 [85] |

| Dry retching, vomiting, burning sensation, belching, spontaneous abortion | Smith et al., 2004 [79] |

| Dizziness, heartburn | Basirat et al., 2009 [86] |

| Drowsiness, heartburn | Pongrojpaw et al., 2007 [75] |

| Spontaneous abortion | Ensiyehh et al., 2009 [83] |

| Spontaneous abortion | Fisher Rasmussen et al., 1991 [63] |

| Heartburn | Saberie et al., 2013 [76] |

| Heartburn | Saberie et al., 2014 [77] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanisiere, J.; Mousset, P.-Y.; Lafay, S. How Safe Is Ginger Rhizome for Decreasing Nausea and Vomiting in Women during Early Pregnancy? Foods 2018, 7, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7040050

Stanisiere J, Mousset P-Y, Lafay S. How Safe Is Ginger Rhizome for Decreasing Nausea and Vomiting in Women during Early Pregnancy? Foods. 2018; 7(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanisiere, Julien, Pierre-Yves Mousset, and Sophie Lafay. 2018. "How Safe Is Ginger Rhizome for Decreasing Nausea and Vomiting in Women during Early Pregnancy?" Foods 7, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7040050

APA StyleStanisiere, J., Mousset, P.-Y., & Lafay, S. (2018). How Safe Is Ginger Rhizome for Decreasing Nausea and Vomiting in Women during Early Pregnancy? Foods, 7(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7040050