Preparation and Study on Sulfated Nanocellulose/Anthocyanin pH-Sensitive Packaging Materials to Track Food Freshness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Instruments

2.1.1. Materials

2.1.2. Experimental Instruments

2.2. Response Surface Analysis for Preparation of Nanocellulose

2.2.1. Preparation of CNC by Acid Hydrolysis

2.2.2. Response Surface Method Design Scheme

2.3. Preparation of Sulfated Nanocellulose/Anthocyanin pH-Sensitive Packaging Materials

2.3.1. Extraction of Anthocyanin from Blueberry

2.3.2. Preparation of pH Sensor

2.4. Structure Characterization of CNC

2.4.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.4.2. TEM Measurement

2.4.3. XRD Spectrum Analysis

2.4.4. FTIR Measurement

2.5. Performance Measurement of Intelligent Indicating Film

2.5.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Observation

2.5.2. FTIR Determination Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

2.5.3. UV–Vis Spectrum of the Thin Film in Different pH Buffer Solutions

2.5.4. Determination of Water Contact Angle

2.5.5. Water Vapor Transmission Test and Water Solubility (WS)

2.5.6. Mechanical Properties

2.5.7. Measurement of Light Stability

2.5.8. Application of Slow-Release Fiber Membrane in Pork Preservation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Establishment and Analysis of Response Surface Method Experimental Model

3.1.1. Response Surface Design and Results

3.1.2. Establishment and Analysis of Yield Model

3.1.3. Interaction of the Factors

3.1.4. Verification of Test Results

3.2. Characterization Analysis of CNC Structure

3.2.1. Observation by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

3.2.2. XRD Spectrum Analysis

3.2.3. FTIR Measurement

3.3. Performance Measurement of pH Sensor

3.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Observation

3.3.2. FTIR Measurement

3.3.3. Analysis of the Film in Different pH Buffer Solutions

3.3.4. Determination of Water Contact Angle

3.3.5. Analysis of Water Vapor Transmission Rate

3.3.6. Mechanical Properties Measurement

3.3.7. Analysis of Light Stability

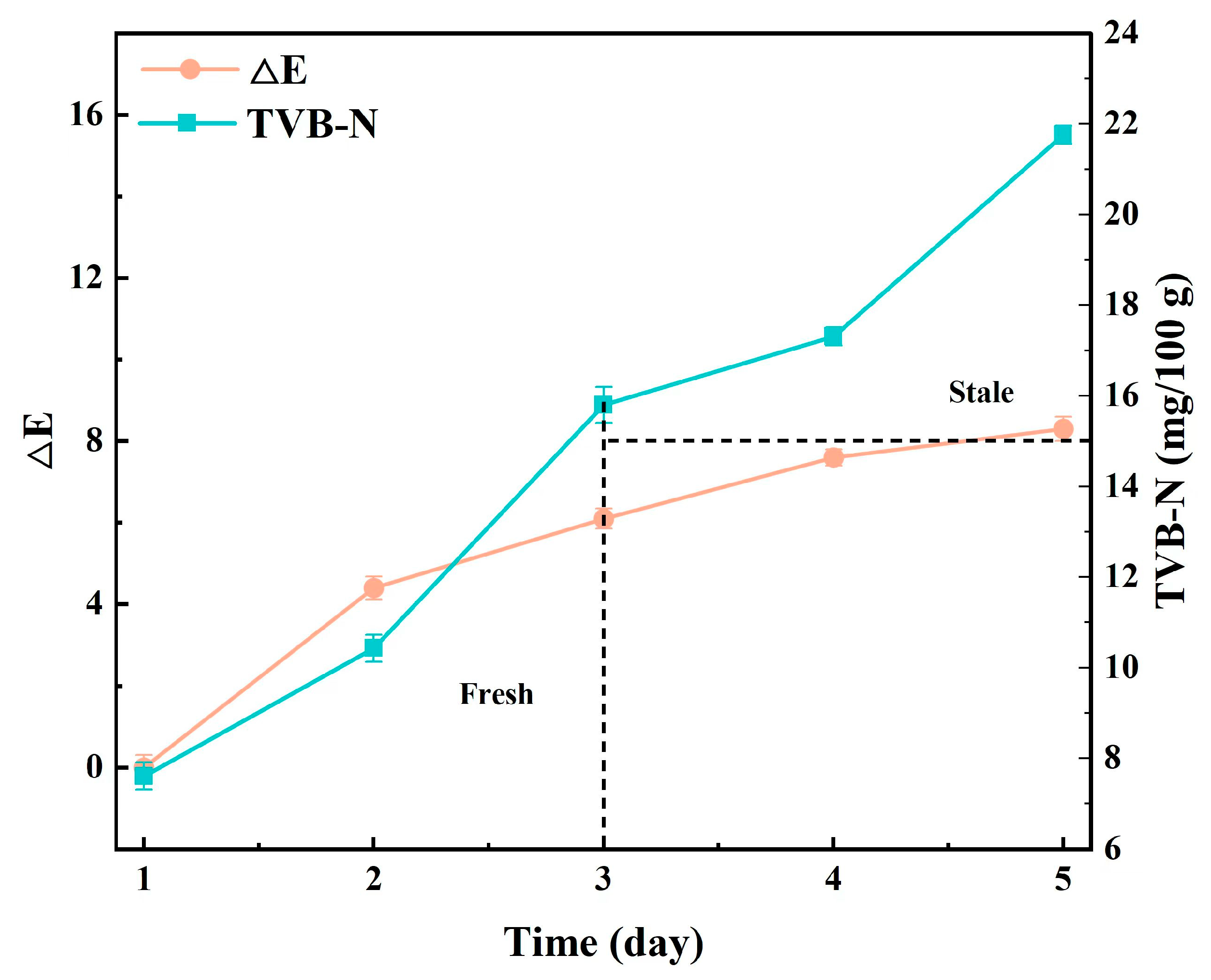

3.3.8. Visual Intelligence Perception of Pork Freshness

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sani, M.A.; Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Tavassoli, M.; Mohammadi, K.; McClements, D.J. Recent advances in the development of smart and active biodegradable packaging materials. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q. Application of Chemical Instrument Analysis Technology in Quality Control of Food Testing and Other Fields. Mod. Food 2019, 15, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, C.; Pu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, L.; Cui, Z.; Zhong, Y. Recent advances in pH-responsive freshness indicators using natural food colorants to monitor food freshness. Foods 2022, 11, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, E.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Jafari, S.M. Smart monitoring of gas/temperature changes within food packaging based on natural colorants. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2885–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pramanik, J.; Batta, K.; Bamal, P.; Prajapati, B.; Singh, S. Applications of value-added natural dye fortified with biopolymer-based food packaging: Sustainability through smart and sensible applications. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhong, J.; McClements, D.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Jin, Z.; Chen, L. Stability enhancement methods for natural pigments in intelligent packaging: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 6233–6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, I.; Yang, T. Biopolymer-based intelligent packaging integrated with natural colourimetric sensors for food safety and sustainability. Anal. Sci. Adv. 2024, 5, e2300065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, H.E.; Hashim, S.B.H.; Mahunu, G.K.; Arslan, M.; Shi, J.; Mariod, A.A.; Zhang, J.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Zhai, X.; Musa, T.H.; et al. Smart films fabricated from natural pigments for measurement of total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) content of meat for freshness evaluation: A systematic review. Food Chem. 2022, 396, 133674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Zhao, B.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Qiao, X. Research Progress on Microbial Spoilage and Volatile Odor in Packaged Chilled Meat. Shipin Kexue 2021, 42, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ramaswamy, S.; Xu, F. Smart colorimetric sensing films with high mechanical strength and hydrophobic properties for visual monitoring of shrimp and pork freshness. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 309, 127752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.V.; Dang, T.H.; Chen, B.H. Synthesis of intelligent pH indicative films from chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol)/anthocyanin extracted from red cabbage. Polymers 2019, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezati, P.; Bang, Y.J.; Rhim, J.W. Preparation of a shikonin-based pH-sensitive color indicator for monitoring the freshness of fish and pork. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; El-Sayed, S.M. Bionanocomposites materials for food packaging applications: Concepts and future outlook. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 193, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputri, L.N.; Fadhil, M.M.; Pratiwi, A.R.; Anggraini, N.; Hadisoebroto, R.; Pradana, R.A.; Nugrahapraja, H. A critical review on sustainable cellulose materials and its multifaceted applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 205, 117535. [Google Scholar]

- Tabatabaei, R.H.; Jafari, S.M.; Mirzaei, H.; Nafchi, A.M.; Dehnad, D. Preparation and characterization of nano-SiO2 reinforced gelatin-k-carrageenan biocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Huo, R.; Cui, Z. Preparation of an indicator film based on pectin, sodium alginate, and xanthan gum containing blueberry anthocyanin extract and its application in blueberry freshness monitoring. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Gao, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. Improvement and optimization of the pH difference method for the determination of anthocyanins in black wolfberry and its products. Food Ferment. Ind. 2022, 50, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Divband, B.; Ehsani, A.; McClements, D.J. Nanocomposite films consisting of functional nanoparticles (TiO2 and ZnO) embedded in 4A-Zeolite and mixed polymer matrices (gelatin and polyvinyl alcohol). Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Tavassoli, M.; Mohammadian, E.; Ehsani, A.; Khaniki, G.J.; Priyadarshi, R.; Rhim, J.-W. pH-responsive color indicator films based on methylcellulose/chitosan nanofiber and barberry anthocyanins for real-time monitoring of meat freshness. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 166, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J. A Study on the Electrical Properties of Silicone Rubber Insulating Materials at Low Temperatures. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E96-05; Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2005.

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yong, H.; Qin, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, J. Development of multifunctional food packaging films based on chitosan, TiO2 nanoparticles and anthocyanin-rich black plum peel extract. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 94, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Zou, X.; Shi, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Holmes, M.; et al. Amine-responsive bilayer films with improved illumination stability and electrochemical writing property for visual monitoring of meat spoilage. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 302, 127130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Lee, J.Y.; Lacroix, M.; Han, J. Intelligent pH indicator film composed of agar/potato starch and anthocyanin extracts from purple sweet potato. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.237-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of pH Value of Foods. National Health and Family Planning Commission: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 5009.228-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Volatile Base Nitrogen in Foods. National Health and Family Planning Commission: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 4789.2-2022; National Food Safety Standard—Food Microbiological Examination: Aerobic Plate Count. National Health Commission; State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Lu, P.-J.; Huang, S.-C.; Chen, Y.-P.; Chiueh, L.-C.; Shih, D.Y.-C. Analysis of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in cosmetics. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015, 23, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Creely, J.J.; Martin, A.E., Jr.; Conrad, C.M. An empirical method for estimating The crystallinity of native cellulose was measured using an X-ray diffractometer. Text. Res. J. 1959, 29, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asha, K.K.; Cintil, J.; Rohith, K.R.; George, K.E. Sisal nanofibril reinforced polypropylene/polystyrene blends: Morphology, mechanical, dynamic mechanical and water transmission studies. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 71, 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Xu, D.; Lan, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wu, S.; Luo, Z. Preparation and Properties of Regenerated Cellulose Membrane from Hemp Noils. Cellul. Sci. Technol. 2023, 31, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, M.A.; Tavassoli, M.; Salim, S.A.; Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Mcclements, D.J. Development of green halochromic smart and active packaging materials: TIO2 nanoparticle- and anthocyanin-loaded gelatin/κ-carrageenan films. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Chen, X.; Li, N.; Xie, T.; Guo, Y.; Fu, Y.; Jiao, T. A convenient synthesis of gold nanoparticles in Spirulina extract for rapid visual detection of dopamine in human urine. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 650, 129675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. Preparation, Characterization and Application Research of Cannabis Nanocellulose. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arfat, Y.A.; Benjakul, S.; Prodpran, T.; Sumpavapol, P.; Songtipya, P. Properties and antimicrobial activity of fish protein isolate/fish skin gelatin film containing basil leaf essential oil and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 41, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Kong, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J. Polymer grafting on cellulose nanocrystals initiated by ceric ammonium nitrate: Is it feasible under acid-free conditions? Green Chem. 2021, 23, 8581–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yao, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, H.; Liu, W. Preparation and Properties of Modified Nanocellulose/Poly(lactic acid) Composite Materials. Fine Chem. 2020, 37, 45–50+79. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Mohammadian, E.; Rhim, J.-W.; Jafari, S.M. pH-sensitive (halochromic) smart packaging films based on natural food colorants for the monitoring of food quality and safety. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 105, 93–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumee, J.; Kumpun, S.; Nimanong, N.; Banditaubol, N.; Ohama, P. Colorimetric biofilm sensor with anthocyanin for monitoring fresh pork spoilage. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Han, L.; Zhai, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, A.; Wu, T.; Hou, H. Etherification modification of microcrystalline cellulose and its application in starch films. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, K.M.M.N.; de Carvalho, D.E.L.; Valente, V.M.M.; Rubio, J.C.C.; Faria, P.E.; Silva-Caldeira, P.P. Concomitant and controlled release of furazolidone and bismuth(Ⅲ) incorporated in a cross-linked sodium alginate-carboxymethyl cellulose hydrogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberlintner, A.; Likozar, B.; Novak, U. Effect of environment on acetylated cellulose nanocrystal-reinforced biopolymers films. Polymers 2023, 15, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargarzadeh, H.; Ahmad, I.; Thomas, S.; Dufresne, A. Handbook of Nanocellulose and Cellulose Nanocomposites; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.; Sun, G.; Cao, L.; Li, J.; Wang, L. A pH and NH3 sensing intelligent film based on Artemisia sphaerocephala Krasch. gum and red cabbage anthocyanins anchored by carboxymethyl cellulose sodium added as a host complex. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, H.; Wang, X.; Bai, R.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Development of antioxidant and intelligent pH-sensing packaging films by incorporating purplefleshed sweet potato extract into chitosan matrix. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 90, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadekar, N.R.; Karande, V.S.; Vigneshwaran, N.; Bharimalla, A.K.; Mhaske, S.T. Preparation of nano cellulose fibers and its application in kappa-carrageenan based film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J. Effect of Anthocyanins on Colorimetric Indicator Film Properties. Coatings 2023, 3, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, M. Encyclopedia of Cancer; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karma, I.G.M. Determination and measurement of color dissimilarity. Int. J. Eng. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 5, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xie, D.; Mei, Y. Preparation, Modification and Application of Nano-Titanium Dioxide in Polymer-Based Composites: A Review. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 39, 17. [Google Scholar]

- GB 2707-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Fresh (Frozen) Livestock and Poultry Products. National Health and Family Planning Commission; State Food and Drug Administration: Beijing, China, 2016.

| Factor | Horizontal | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | |

| A—sulfuric acid concentration (%) | 50 | 60 | 70 |

| B—temperature (℃) | 35 | 45 | 55 |

| C—time (min) | 55 | 90 | 125 |

| Nomination of Composite Films | Composite Membrane Components |

|---|---|

| TG/GG-CNC | Tara glue (TiO2 layer)/junction cold glue (anthocyanin layer)—no cellulose added |

| TG/GG-CNC2 | Tara glue (TiO2 layer)/junction cold glue (anthocyanin layer)—added 2% cellulose |

| TG/GG-CNC4 | Tara glue (TiO2 layer)/junction cold glue (anthocyanin layer)—added 4% cellulose |

| TG/GG-CNC6 | Tara glue (TiO2 layer)/junction cold glue (anthocyanin layer)—added 6% cellulose |

| TG/GG-CNC8 | Tara glue (TiO2 layer)/junction cold glue (anthocyanin layer)—added 8% cellulose |

| TG/GG | Tara glue–set cold glue blank sample |

| TG-221AN/GG | Tara gum–anthocyanin/gelatin |

| TG/TiO2-AN/GG | Tara gum/TiO2–anthocyanin/vermicell |

| Test Number | A—Sulfuric Acid Concentration | B—Temperature | C—Time | Yield (%) | Predicted Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | 35 | 90 | 35.56 | 33.37 |

| 2 | 70 | 35 | 90 | 12.5 | 10.21 |

| 3 | 50 | 55 | 90 | 54.94 | 57.23 |

| 4 | 70 | 55 | 90 | 29.11 | 31.3 |

| 5 | 50 | 45 | 55 | 34.47 | 33.02 |

| 6 | 70 | 45 | 55 | 2.85 | 1.49 |

| 7 | 50 | 45 | 125 | 46.53 | 47.89 |

| 8 | 70 | 45 | 125 | 28.89 | 30.34 |

| 9 | 60 | 35 | 55 | 8.39 | 12.04 |

| 10 | 60 | 55 | 55 | 52.93 | 52.1 |

| 11 | 60 | 35 | 125 | 50.66 | 51.49 |

| 12 | 60 | 55 | 125 | 60.03 | 56.38 |

| 13 | 60 | 45 | 90 | 61.15 | 62.42 |

| 14 | 60 | 45 | 90 | 64.58 | 62.42 |

| 15 | 60 | 45 | 90 | 59.5 | 62.42 |

| 16 | 60 | 45 | 90 | 63.02 | 62.42 |

| 17 | 60 | 45 | 90 | 63.87 | 62.42 |

| Type | Continuous p-Value | Misfit p Value | Regulation of R2 | Predict R2 | Bear Fruit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 0.0366 | 0.0003 | 0.3460 | 0.1623 | - |

| 2FI | 0.7758 | 0.0002 | 0.2349 | −0.3150 | |

| Quadratic | <0.0001 | 0.0955 | 0.9752 | 0.8635 | Suggested |

| Variance Source | Quadratic Sum | Free Degree | Mean Square | F Price | Probability > F | Bear Fruit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean vs. Total | 31,259.52 | 1 | 31,259.52 | |||

| Linear vs. Mean | 3170.80 | 3 | 1056.93 | 3.82 | 0.0366 | |

| 2FI vs. Linear | 360.01 | 3 | 120.00 | 0.37 | 0.7758 | |

| Quadratic vs. 2FI | 3161.96 | 3 | 1053.99 | 100.65 | <0.0001 | Suggested |

| Cubic vs. Quadratic | 56.03 | 3 | 18.68 | 4.33 | 0.0955 | |

| Residual | 17.27 | 4 | 4.32 | |||

| Amount to | 38,025.60 | 17 | 2236.80 |

| Variance Source | Quadratic Sum | Free Degree | Mean Square | F Price | Probability > F | Bear Fruit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 3578.00 | 9 | 397.56 | 92.09 | 0.0003 | |

| 2FI | 3217.99 | 6 | 536.33 | 124.24 | 0.0002 | |

| Quadratic | 56.03 | 3 | 18.68 | 4.33 | 0.0955 | Suggested |

| Pure Error | 17.27 | 4 | 4.32 |

| Type | Sample Standard Deviation | Degree of Fitting | Corrected Fit | Predicted Goodness of Fit | Definition | Bear Fruit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 16.63 | 0.4686 | 0.3460 | 0.1623 | 5667.64 | |

| 2FI | 17.99 | 0.5218 | 0.2349 | −0.3150 | 8897.45 | |

| Quadratic | 3.24 | 0.9892 | 0.9752 | 0.8635 | 923.53 | Suggested |

| Cubic | 2.08 | 0.9974 | 0.9898 | + |

| Source | Sum of Squares of Deviations | Free Degree | Mean Square | F Price | p Price | Conspicuousness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 6692.77 | 9 | 743.64 | 71.01 | <0.0001 | ** |

| A—sulfuric acid concentration | 1204.18 | 1 | 1204.18 | 114.99 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B—temperature | 1010.25 | 1 | 1010.25 | 96.47 | <0.0001 | ** |

| C—time | 956.38 | 1 | 956.38 | 91.33 | <0.0001 | ** |

| AB | 1.92 | 1 | 1.92 | 0.18 | 0.6815 | |

| AC | 48.86 | 1 | 48.86 | 4.67 | 0.0676 | |

| BC | 309.23 | 1 | 309.23 | 29.53 | 0.0010 | ** |

| A2 | 2057.77 | 1 | 2057.77 | 196.51 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B2 | 223.73 | 1 | 223.73 | 21.37 | 0.0024 | ** |

| C2 | 619.73 | 1 | 619.73 | 59.18 | 0.0001 | ** |

| Residual | 73.30 | 7 | 10.47 | |||

| Fictitious term | 56.03 | 3 | 18.68 | 4.33 | 0.0955 | ns |

| Pure error | 17.27 | 4 | 4.32 | |||

| Sum | 6766.08 | 16 |

| Project | Numeric Value | Project | Numeric Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard error | 3.24 | Model correlation coefficient (R2) | 0.9892 |

| Mean | 42.88 | Adjusted coefficient of determination (R2Adj) | 0.9752 |

| Coefficient of variation/% | 7.55 | Predetermined coefficient of determination (R2Pre) | 0.8635 |

| Sum of squared prediction errors | 923.53 | Relative accuracy | 24.552 |

| Granular Type | Surface | Microscopic Morphology | Size | Crystallinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCC | White opaque powder | Dense irregular granule | 10–50 μm | 55–75% |

| MFC/NFC | Opaque to translucent gel or paste | Long and entangled fiber meshes | 10–100 nm | 50–70% |

| NFC | Opaque to translucent gel or paste | Long and entangled fiber meshes | 5–60 nm | - |

| CNC | Suspension with milky light, drying to form a transparent film | Short rod-like rigid nanocrystals | 3–50 nm, length 50–500 nm | 54–88% |

| t-CNC | Suspension or dispersion in an organic solvent | Short stick, surface chemical group changed | 3–50 nm | 80–90% |

| pH | Simple | L | a | b | pH | Simple | L | a | b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH3 |  | 49.5 | 38.8 | 4.5 | pH4 |  | 53.6 | 31.2 | 5.2 |

| pH5 |  | 48.2 | 21.1 | 5.3 | pH6 |  | 45.9 | 14.7 | 1.9 |

| pH7 |  | 40.2 | 19.3 | 4.1 | pH8 |  | 40.1 | 16.8 | −4.3 |

| pH9 |  | 29.2 | 2.1 | −3.2 | pH10 |  | 43.4 | −0.3 | −5.3 |

| pH11 |  | 53.1 | −0.5 | 7.2 | pH12 |  | 55.2 | 0.4 | 9.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Yuan, Q.; Hsieh, C.-T.; Lou, C.-W.; Lin, J.-H. Preparation and Study on Sulfated Nanocellulose/Anthocyanin pH-Sensitive Packaging Materials to Track Food Freshness. Foods 2026, 15, 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030494

Yang L, Yuan Q, Hsieh C-T, Lou C-W, Lin J-H. Preparation and Study on Sulfated Nanocellulose/Anthocyanin pH-Sensitive Packaging Materials to Track Food Freshness. Foods. 2026; 15(3):494. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030494

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lan, Qianyu Yuan, Chien-Teng Hsieh, Ching-Wen Lou, and Jia-Horng Lin. 2026. "Preparation and Study on Sulfated Nanocellulose/Anthocyanin pH-Sensitive Packaging Materials to Track Food Freshness" Foods 15, no. 3: 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030494

APA StyleYang, L., Yuan, Q., Hsieh, C.-T., Lou, C.-W., & Lin, J.-H. (2026). Preparation and Study on Sulfated Nanocellulose/Anthocyanin pH-Sensitive Packaging Materials to Track Food Freshness. Foods, 15(3), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030494