Improving Lipid Profiles Through Lactobacillus rhamnosus Supplementation in Dyslipidemic Animal Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Criteria for Eligibility

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.5. Meta-Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias in Included Studies

3.4. Meta-Analysis of Lipid Outcomes

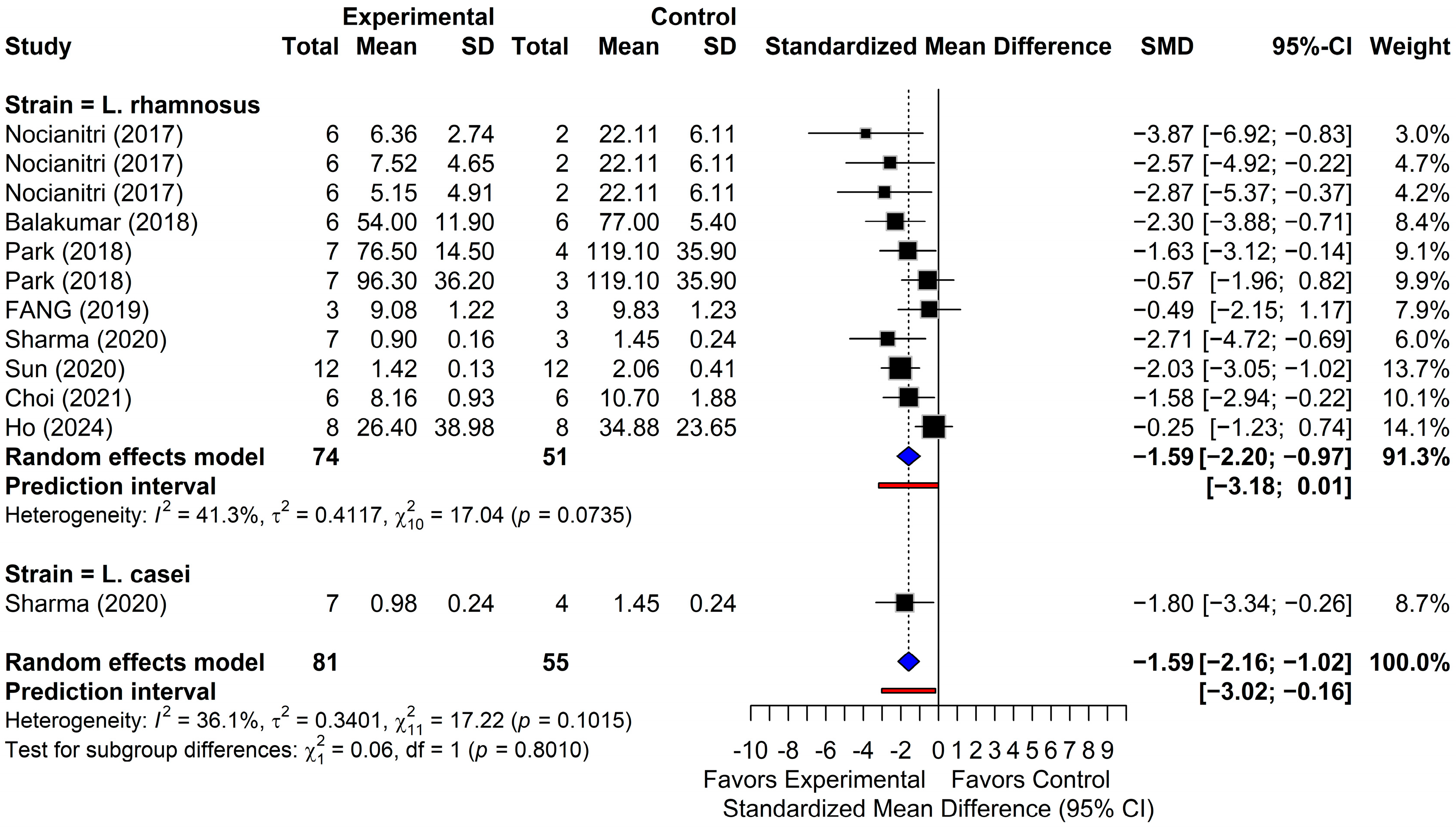

3.4.1. Triglycerides

3.4.2. Total Cholesterol

3.4.3. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

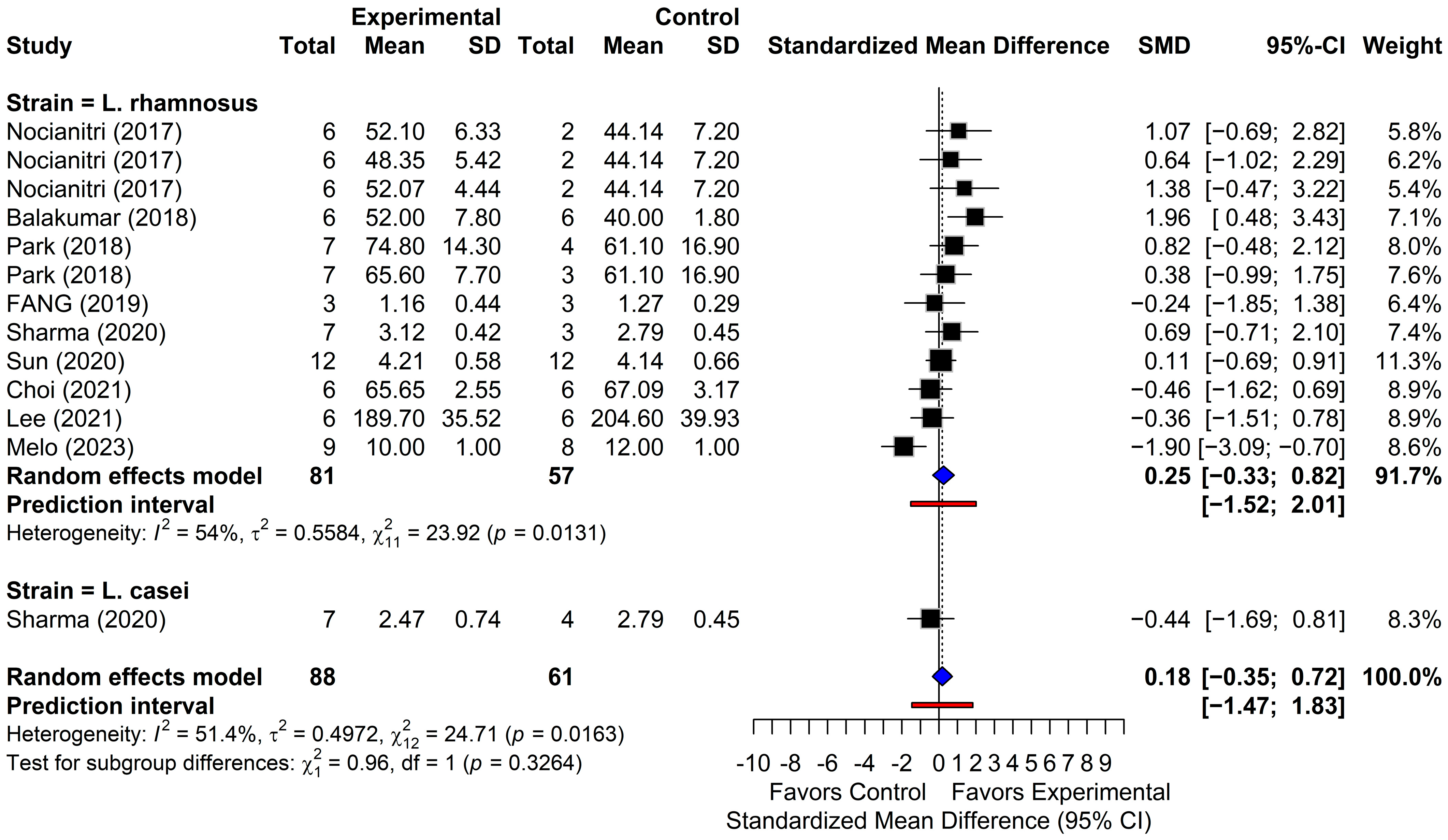

3.4.4. High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

3.4.5. Subgroup Analyses by Intervention Duration, Animal Species, and Diet Type

3.5. Publication Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TG | Triglyceride |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| BSH | Bile salt hydrolase |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SE | Standard error |

| PI | Prediction interval |

References

- Pirillo, A.; Casula, M.; Olmastroni, E.; Norata, G.D.; Catapano, A.L. Global epidemiology of dyslipidaemias. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, M.J.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Amarenco, P.; Andreotti, F.; Borén, J.; Catapano, A.L.; Descamps, O.S.; Fisher, E.; Kovanen, P.T.; Kuivenhoven, J.A.; et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: Evidence and guidance for management. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1345–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N.C.; Watts, G.F.; Eckel, R.H. Statin toxicity: Mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 328–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, E.J.B.; Thongtang, N.; Lee, Z.V.; Hoa, T.; Yee, O.H.; Sukmawan, R. Addressing adherence challenges in long-term statin treatment among Asian populations: Current gaps and proposed solutions. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 23, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-C.; Ki, S.-W.; Kim, H.; Kang, S.; Kim, H.; Go, G.-w. Recent advances in nutraceuticals for the treatment of sarcopenic obesity. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Shi, B. Gut microbiota as a potential target of metabolic syndrome: The role of probiotics and prebiotics. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus beijerinck 1901, and union of lactobacillaceae and leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazalpour, A.; Cespedes, I.; Bennett, B.J.; Allayee, H. Expanding role of gut microbiota in lipid metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2016, 27, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Seaton, S.C.; Ndousse-Fetter, S.; Adhikari, A.A.; DiBenedetto, N.; Mina, A.I.; Banks, A.S.; Bry, L.; Devlin, A.S. A selective gut bacterial bile salt hydrolase alters host metabolism. eLife 2018, 7, e37182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhao, H.-P.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.-H.; Zhang, X.-J.; Guo, Z.-Q.; Jiang, W.-Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, L. From gut microbial ecology to lipid homeostasis: Decoding the role of gut microbiota in dyslipidemia pathogenesis and intervention. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 108680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Covián, D.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Margolles, A.; Gueimonde, M.; De Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Salazar, N. Intestinal short chain fatty acids and their link with diet and human health. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitkunat, K.; Schumann, S.; Nickel, D.; Kappo, K.A.; Petzke, K.J.; Kipp, A.P.; Blaut, M.; Klaus, S. Importance of propionate for the repression of hepatic lipogenesis and improvement of insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2611–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liong, M.T.; Shah, N.P. Bile salt deconjugation ability, bile salt hydrolase activity and cholesterol co-precipitation ability of lactobacilli strains. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, W.; Xia, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. Cholesterol-lowering effect of bile salt hydrolase from a Lactobacillus johnsonii strain mediated by FXR pathway regulation. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriaa, A.; Bourgin, M.; Potiron, A.; Mkaouar, H.; Jablaoui, A.; Gérard, P.; Maguin, E.; Rhimi, M. Microbial impact on cholesterol and bile acid metabolism: Current status and future prospects. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleishman, J.S.; Kumar, S. Bile acid metabolism and signaling in health and disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douillard, F.P.; Ribbera, A.; Järvinen, H.M.; Kant, R.; Pietilä, T.E.; Randazzo, C.; Paulin, L.; Laine, P.K.; Caggia, C.; von Ossowski, I.; et al. Comparative genomic and functional analysis of Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains marketed as probiotics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Zhou, L.; Wu, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, S.X.; Zhang, H.X. Probiotics for the treatment of hyperlipidemia: Focus on gut-liver axis and lipid metabolism. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 214, 107694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olotu, T.; Ferrell, J.M. Lactobacillus sp. For the attenuation of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in mice. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Kang, J.; Choi, S.; Park, H.; Hwang, E.; Kang, Y.; Kim, A.; Holzapfel, W.; Ji, Y. Cholesterol-lowering effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus BFE5264 and its influence on the gut microbiome and propionate level in a murine model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Sun, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Dou, S.; Hua, Q.; Ma, A.; Cai, J. Regulation of gut microflora by Lactobacillus casei zhang attenuates liver injury in mice caused by anti-tuberculosis drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: From biology to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C.E. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Lin, L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: Practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine 2019, 98, e15987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrois, T.L. Systematic reviews: What do you need to know to get started? Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 68, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.-Y.; Li, M.-Y.; Chen, C.; Kang, E.; Cochrane, T. Ten circumstances and solutions for finding the sample mean and standard deviation for meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Aloe, A.M. Evaluation of various estimators for standardized mean difference in meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murad, M.H.; Wang, Z.; Chu, H.; Lin, L. When continuous outcomes are measured using different scales: Guide for meta-analysis and interpretation. BMJ 2019, 364, k4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M. How to understand and report heterogeneity in a meta-analysis: The difference between i-squared and prediction intervals. Integr. Med. Res. 2023, 12, 101014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, G.; Cates, C.J.; Schwarzer, G. Methods for including information from multi-arm trials in pairwise meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2017, 8, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.A.; Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, ED000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2010, 1, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliavaca, C.B.; Stein, C.; Colpani, V.; Barker, T.H.; Ziegelmann, P.K.; Munn, Z.; Falavigna, M.; Group, P.E.R.S.R.M. Meta-analysis of prevalence: I2 statistic and how to deal with heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 2022, 13, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-García, L.; Macarulla, M.T.; Cuevas-Sierra, A.; Martínez, J.A.; Portillo, M.P.; Milton-Laskibar, I. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG administration partially prevents diet-induced insulin resistance in rats: A comparison with its heat-inactivated parabiotic. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 8865–8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocianitri, K.A.; Antara, N.S.; Sugitha, I.M.; Sukrama, I.D.M.; Ramona, Y.; Sujaya, I.N. The effect of two Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains on the blood lipid profile of rats fed with high fat containing diet. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 795. [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar, M.; Prabhu, D.; Sathishkumar, C.; Prabu, P.; Rokana, N.; Kumar, R.; Raghavan, S.; Soundarajan, A.; Grover, S.; Batish, V.K.; et al. Improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity by probiotic strains of indian gut origin in high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6J mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, H.Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xia, J.; Ding, K.; Fang, Z.Y. Probiotic administration of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 attenuates atherosclerotic plaque formation in ApoE-/- mice fed with a high-fat diet. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 3533–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Navik, U.; Tikoo, K. Unveiling the presence of epigenetic mark by Lactobacillus supplementation in high-fat diet-induced metabolic disorder in Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 84, 108442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Wu, T.; Zhang, G.; Liu, R.; Sui, W.; Zhang, M.; Geng, J.; Yin, J.; Zhang, M. Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 improves lipid accumulation in mice fed with a high fat diet via regulating the intestinal microbiota, reducing glucose content and promoting liver carbohydrate metabolism. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9514–9525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-I.; You, S.; Kim, S.; Won, G.; Kang, C.-H.; Kim, G.-H. Weissella cibaria MG5285 and Lactobacillus reuteri MG5149 attenuated fat accumulation in adipose and hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet-induced C57BL/6J obese mice. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 65, 8087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Park, M.H.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, S.H. Antiobesity effect of novel probiotic strains in a mouse model of high-fat diet–induced obesity. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 1054–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, S.Ç.; Saka, M.; Turhan, N.; Hortaç Iştar, E.; Mirza, C.; Bayraktar, N.; Akçil Ok, M. Protective effects of oral Lactobacillus rhamnosus on liver steatosis in rats on high-fat diet. Curr. Top. Nutraceutical Res. 2020, 19, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroline De Oliveira Melo, N.; Cuevas-Sierra, A.; Arellano-Garcia, L.; Portillo, M.P.; Milton-Laskibar, I.; Alfredo Martinez, J. Oral administration of viable or heat-inactivated lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG influences on metabolic outcomes and gut microbiota in rodents fed a high-fat high-fructose diet. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 109, 105808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.-Y.; Chou, Y.-C.; Koh, Y.-C.; Lin, W.-S.; Chen, W.-J.; Tseng, A.-L.; Gung, C.-L.; Wei, Y.-S.; Pan, M.-H. Lactobacillus rhamnosus 069 and Lactobacillus brevis 031: Unraveling strain-specific pathways for modulating lipid metabolism and attenuating high-fat-diet-induced obesity in mice. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 28520–28533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; De Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chu, H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2018, 74, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarezadeh, M.; Musazadeh, V.; Faghfouri, A.H.; Roshanravan, N.; Dehghan, P. Probiotics act as a potent intervention in improving lipid profile: An umbrella systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-B.; Lee, B.H. Biochemical and molecular insights into bile salt hydrolase in the gastrointestinal microflora—A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 18, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M. III. Regulation of bile acid synthesis: Past progress and future challenges. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003, 284, G551–G557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, H.M.; Jarrett, K.E.; De Aguiar Vallim, T.Q.; Tarling, E.J. Pathways and molecular mechanisms governing LDL receptor regulation. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go, G.-w. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6) is a novel nutritional therapeutic target for hyperlipidemia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and atherosclerosis. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4453–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, M. Regulation of cholesterol transporters by nuclear receptors. Receptors 2023, 2, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.; Huang, J.; Wen, S.; Chai, X.; Zhang, S.; Yu, H.; Lin, B.; Liang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zeng, J. Lactobacillus rhamnosus B16 regulates lipid metabolism homeostasis by producing acetic acid. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.s.; Ju, J.h.; Lee, J.e.; Park, H.j.; Lee, J.m.; Shin, H.k.; Holzapfel, W.; Park, K.y.; Do, M.S. The probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus BFE5264 and Lactobacillus plantarum NR74 promote cholesterol efflux and suppress inflammation in thp-1 cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, K.P.; Lim, H.Y.; Angeli, V. Leukocyte trafficking via lymphatic vessels in atherosclerosis. Cells 2021, 10, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, P.; Shen, L.; Niu, L.; Tan, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, L.; Hao, X.; Li, X.; et al. Short-chain fatty acids and their association with signalling pathways in inflammation, glucose and lipid metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Park, Y.; Shin, M.; Kim, J.-M.; Go, G.-w. Betulinic acid suppresses de novo lipogenesis by inhibiting insulin and IGF1 signaling as upstream effectors of the nutrient-sensing mTOR pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 12465–12473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lv, X.; Qi, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, M.; Wang, B.; Cao, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supernatant improves GLP-1 secretion through attenuating l cell lipotoxicity and modulating gut microbiota in obesity. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, T.; Sun, Z.; Pan, Y.; Deng, X.; Yuan, G. Glucagon-like peptide-1: New regulator in lipid metabolism. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liang, H. Effect of Lactobacillus casei on lipid metabolism and intestinal microflora in patients with alcoholic liver injury. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stogiannis, D.; Siannis, F.; Androulakis, E. Heterogeneity in meta-analysis: A comprehensive overview. Int. J. Biostat. 2024, 20, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, L.; Ikeda, N.; Fukui, N.; Yaju, Y.; Tsuruta, H.; Moons, K.G.M. More than numbers: The power of graphs in meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 169, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.G.; Higgins, J.P.T. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Ikewaki, K. Beyond high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol: Unraveling the complexity of high-density lipoprotein functionality. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2025, 32, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, M. HDL, cholesterol efflux, and ABCA1: Free from good and evil dualism. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 150, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, H.R.; Sahoo, D. SR-B1’s next top model: Structural perspectives on the functions of the HDL receptor. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2022, 24, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Li, H.; Wen, K.; Bao, J.; Wu, X.; Sun, R.; Abudukeremu, A.; Wang, Y.; et al. Proteomic and functional analysis of HDL subclasses in humans and rats: A proof-of-concept study. Lipids Health Dis. 2023, 22, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, L.; Bielczyk-Maczynska, E. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol: How studying the ‘good cholesterol’ could improve cardiovascular health. Open Biol. 2025, 15, 240372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohatgi, A.; Westerterp, M.; von Eckardstein, A.; Remaley, A.; Rye, K.A. HDL in the 21st century: A multifunctional roadmap for future HDL research. Circulation 2021, 143, 2293–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, K.; Ikewaki, K. Microbiota and HDL metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2018, 29, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.A.; Kim, J. Effect of probiotics on blood lipid concentrations: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2015, 94, e1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lith, H.A.; Laarakker, M.C.; Lozeman-van’t Klooster, J.G.; Ohl, F. Chromosomal assignment of quantitative trait loci influencing baseline circulating total cholesterol level in male laboratory mice: Report of a consomic strain survey and comparison with published results. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadzadeh, K.; Roshdi Dizaji, S.; Yousefifard, M. Lack of concordance between reporting guidelines and risk of bias assessments of preclinical studies: A call for integrated recommendations. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 2557–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilkenny, C.; Parsons, N.; Kadyszewski, E.; Festing, M.F.W.; Cuthill, I.C.; Fry, D.; Hutton, J.; Altman, D.G. Survey of the quality of experimental design, statistical analysis and reporting of research using animals. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Almada, G.; Mejía-León, M.E.; Salazar-López, N.J. Probiotic, postbiotic, and paraprobiotic effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus as a modulator of obesity-associated factors. Foods 2024, 13, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Jia, W. Lactobacillus casei-derived postbiotics inhibited digestion of triglycerides, glycerol phospholipids and sterol lipids via allosteric regulation of BSSL, PTL and PLA2 to prevent obesity: Perspectives on deep learning integrated multi-omics. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 7439–7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amobonye, A.; Pillay, B.; Hlope, F.; Asong, S.T.; Pillai, S. Postbiotics: An insightful review of the latest category in functional biotics. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Year | Animal | Sex (M 2)/F 3)) | Age (wk) | n | Strain | Duration (wk 1)) | Dose (as Reported) | Disease Induction | Outcomes (Lipid Profile) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nocianitri et al. [39] | 2017 | Wistar rats | M | - | 6 | L. rhamnosus SKG34, L. rhamnosus FBB42, L. rhamnosus (SKG34 + FBB42) | 4 | 0.5 mL of cell suspension (108 cells/mL) | HFD 5) | Serum TG 10), TC 11), LDL-C 12), HDL-C 13) |

| Balakumar et al. [40] | 2018 | B6 4) | M | 8–10 | 6 | L. rhamnosus GG | 24 | 1.5 × 109 colonies/mouse/day | HFD | Serum TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C |

| Park et al. [22] | 2018 | B6TacN | M | 3 | 7–8 | L. rhamnosus GG, L. rhamnosus BFE5264 | 9 | 1 × 1010 CFU 9) | HC 6) | Serum TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C |

| FANG et al. [41] | 2019 | ApoE −/− mice | M | 8 | 3 | L. rhamnosus GR-1 (L) L. rhamnosus GR-1 (H) | 12 | L: 5 × 107 CFU H: 5 × 108 CFU | HFCD 7) | Serum TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C |

| Sharma et al. [42] | 2020 | SD rats | M | 6 | 7 | L. casei ATCC 393, L. rhamnosus ATCC53103 | 12 | 1 × 109 CFU | HFD | Plasma TG, TC LDL-C, HDL-C |

| Sun et al. [43] | 2020 | B6 | F | 4 | 12 | L. rhamnosus LRa05 | 8 | 1 × 109 CFU | HFD | Serum TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C |

| Choi et al. [44] | 2021 | B6 | M | 4 | 6 | L. rhamnosus MG4502 | 8 | 2 × 108 CFU | HFD | Serum TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C |

| Lee et al. [45] | 2021 | B6 | M | 10 | 6 | L. rhamnosus 86 | 12 | 1 × 1010 CFU | HFD | Serum TG, TC, HDL-C |

| Özbek et al. [46] | 2021 | SD rats | M | 6–8 | 8 | L. rhamnosus GG | 12 | 1 × 109 CFU | HFD | Serum TC |

| Arellano-García et al. [38] | 2023 | Wistar rats | M | 8–9 | 8–9 | L. rhamnosus GG | 6 | 1 × 109 CFU | HFHF 8) | Serum TG |

| Melo et al. [47] | 2023 | Wistar rats | M | 8–9 | 8–9 | L. rhamnosus GG | 6 | 1 × 109 CFU | HFHF | Serum TG, TC, HDL-C |

| Ho et al. [48] | 2024 | B6 | M | 4 | 8 | L. rhamnosus SG069 | 12 | 5 × 108 CFU | HFD | Serum TG, TC, LDL-C |

| Outcome | Moderator | Subgroup | k (Comparisons) | Pooled SMDs (95% CI 1)) | I2 (%) | p-Value (Subgroup Difference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG 3) | Duration | ≥8 wk | 10 | −1.21 (−1.87 to −0.55) | 57.1 | 0.3134 |

| <8 wk | 5 | −1.78 (−2.68 to −0.89) | 32.8 | |||

| Species | Mice | 8 | −1.02 (−1.75 to −0.29) | 60.7 | 0.0985 | |

| Rats | 7 | −1.86 (−2.53 to −1.19) | 6.1 | |||

| Diet type | HFD 2) | 10 | −1.56 (−2.14 to −0.97) | 33.7 | p < 0.05 | |

| HFD + Fructose | 2 | −2.27 (−4.52 to −0.02) | 81.2 | |||

| Other/Combined | 3 | −0.22 (−1.02 to 0.59) | 0.0 | |||

| TC 4) | Duration | ≥8 wk | 11 | −0.87 (−1.44 to −0.31) | 51.9 | 0.8303 |

| <8 wk | 4 | −0.78 (−1.48 to −0.07) | 0.0 | |||

| Species | Mice | 8 | −1.02 (−1.55 to −0.49) | 34.5 | 0.3636 | |

| Rats | 7 | −0.62 (−1.30 to 0.05) | 35.8 | |||

| Diet type | HFD | 11 | −1.01 (−1.59 to −0.42) | 50.2 | 0.3027 | |

| Other/Combined | 4 | −0.55 (−1.19 to 0.08) | 0.0 | |||

| LDL-C 5) | Duration | ≥8 wk | 9 | −1.39 (−1.98 to −0.81) | 35.8 | 0.0503 |

| <8 wk | 3 | −2.99 (−4.48 to −1.50) | 0.0 | |||

| Species | Mice | 7 | −1.24 (−1.89 to −0.59) | 40.7 | p < 0.05 | |

| Rats | 5 | −2.48 (−3.42 to −1.53) | 0.0 | |||

| Diet type | HFD | 9 | −1.88 (−2.58 to −1.17) | 41.2 | 0.0892 | |

| Other/Combined | 3 | −0.91 (−1.77 to −0.04) | 0.0 | |||

| HDL-C 6) | Duration | ≥8 wk | 9 | 0.19 (−0.24 to 0.62) | 23.2 | 0.9994 |

| <8 wk | 4 | 0.19 (−1.38 to 1.76) | 77.8 | |||

| Species | Mice | 7 | 0.24 (−0.30 to 0.77) | 32.9 | 0.8509 | |

| Rats | 6 | 0.12 (−0.91 to 1.15) | 66.9 | |||

| Diet type | HFD | 9 | 0.34 (−0.19 to 0.87) | 32.6 | 0.3877 | |

| Other/Combined | 4 | −0.26 (−1.49 to 0.98) | 71.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chung, S.; Jeong, J.; Park, Y.; Lee, B.; Kang, S.; Go, G.-w. Improving Lipid Profiles Through Lactobacillus rhamnosus Supplementation in Dyslipidemic Animal Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2026, 15, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030465

Chung S, Jeong J, Park Y, Lee B, Kang S, Go G-w. Improving Lipid Profiles Through Lactobacillus rhamnosus Supplementation in Dyslipidemic Animal Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods. 2026; 15(3):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030465

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Sungmin, Jiill Jeong, Yeonwoo Park, Bogyeong Lee, Sumin Kang, and Gwang-woong Go. 2026. "Improving Lipid Profiles Through Lactobacillus rhamnosus Supplementation in Dyslipidemic Animal Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Foods 15, no. 3: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030465

APA StyleChung, S., Jeong, J., Park, Y., Lee, B., Kang, S., & Go, G.-w. (2026). Improving Lipid Profiles Through Lactobacillus rhamnosus Supplementation in Dyslipidemic Animal Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods, 15(3), 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030465