Influence of Heat Treatment Prior to Fortification on Goitrogenic Compounds, Iodine Stability and Antioxidant Activity in Cauliflower

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Iodine Matrix

2.1.2. HPLC

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation Conditions

- cooking in boiling water covered (100 °C; 15 min)—BWC,

- cooking in boiling water uncovered (100 °C; 15 min)—BWU,

- steamed (100 °C; 100% steam/10 min) in a convection oven (Rational, Landsberg am Lech, Germany)—CO.

2.2.2. Impregnation Conditions

2.2.3. Storage Conditions of Fortified Vegetables

2.2.4. Stability of Iodine

2.2.5. Sample Preparation for HPLC

2.2.6. HPLC Analysis

2.2.7. Antioxidant Activity

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

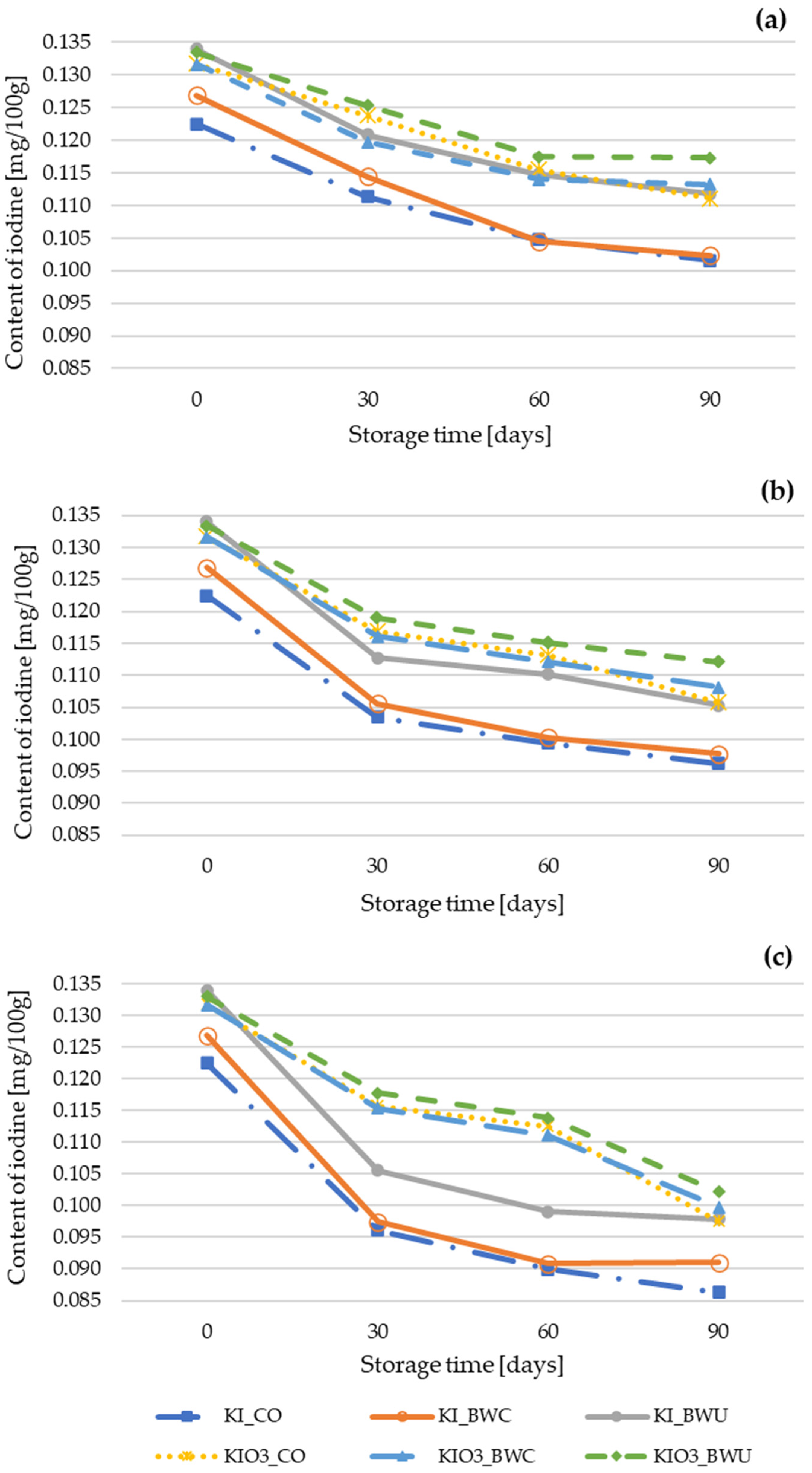

3.1. The Influence of Cauliflower Heat Treatment Conditions on Iodine Retention and Storage Stability

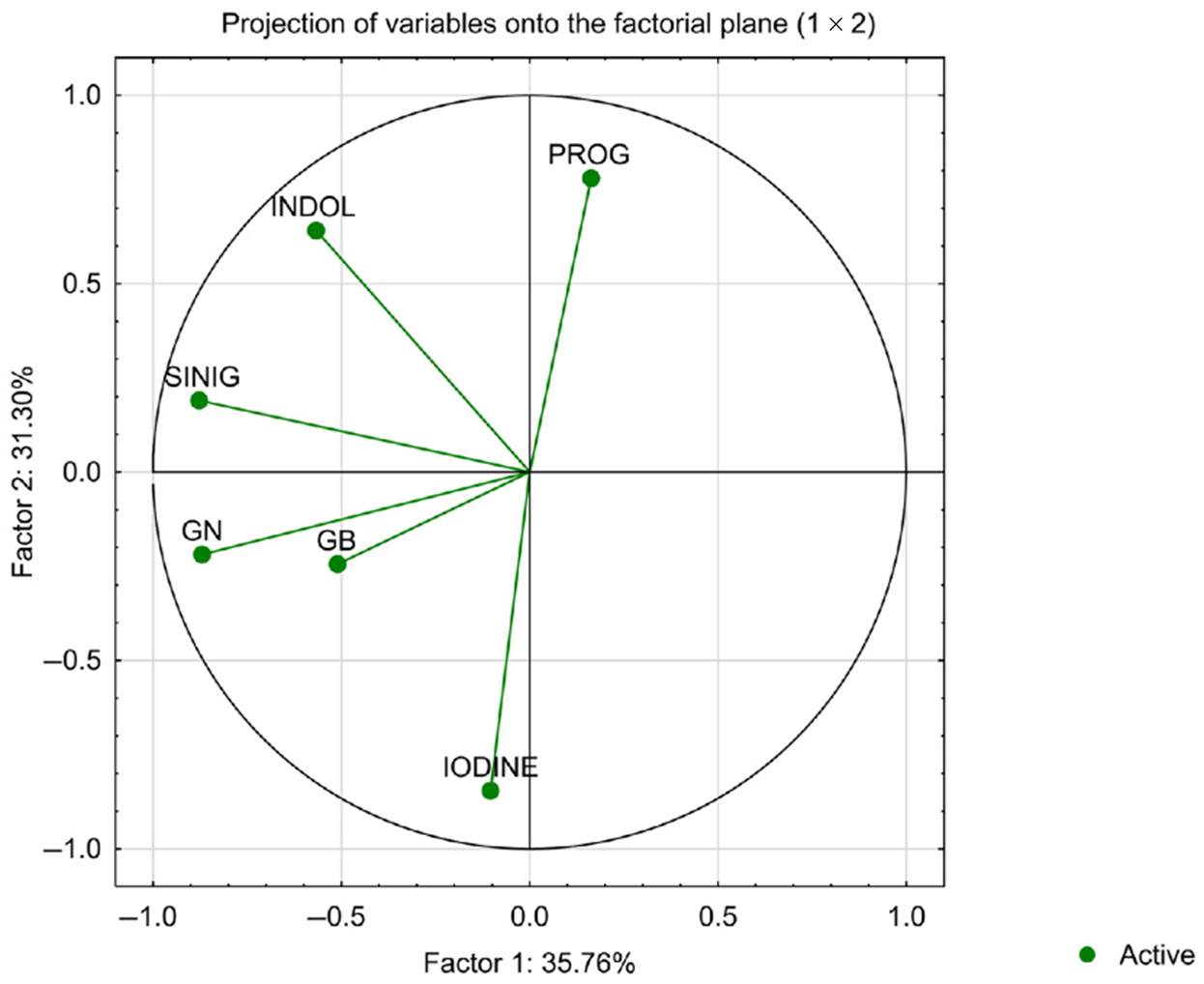

3.2. Associations Between Iodine Content and Selected Phenolic Compounds

3.3. Antioxidant Activity

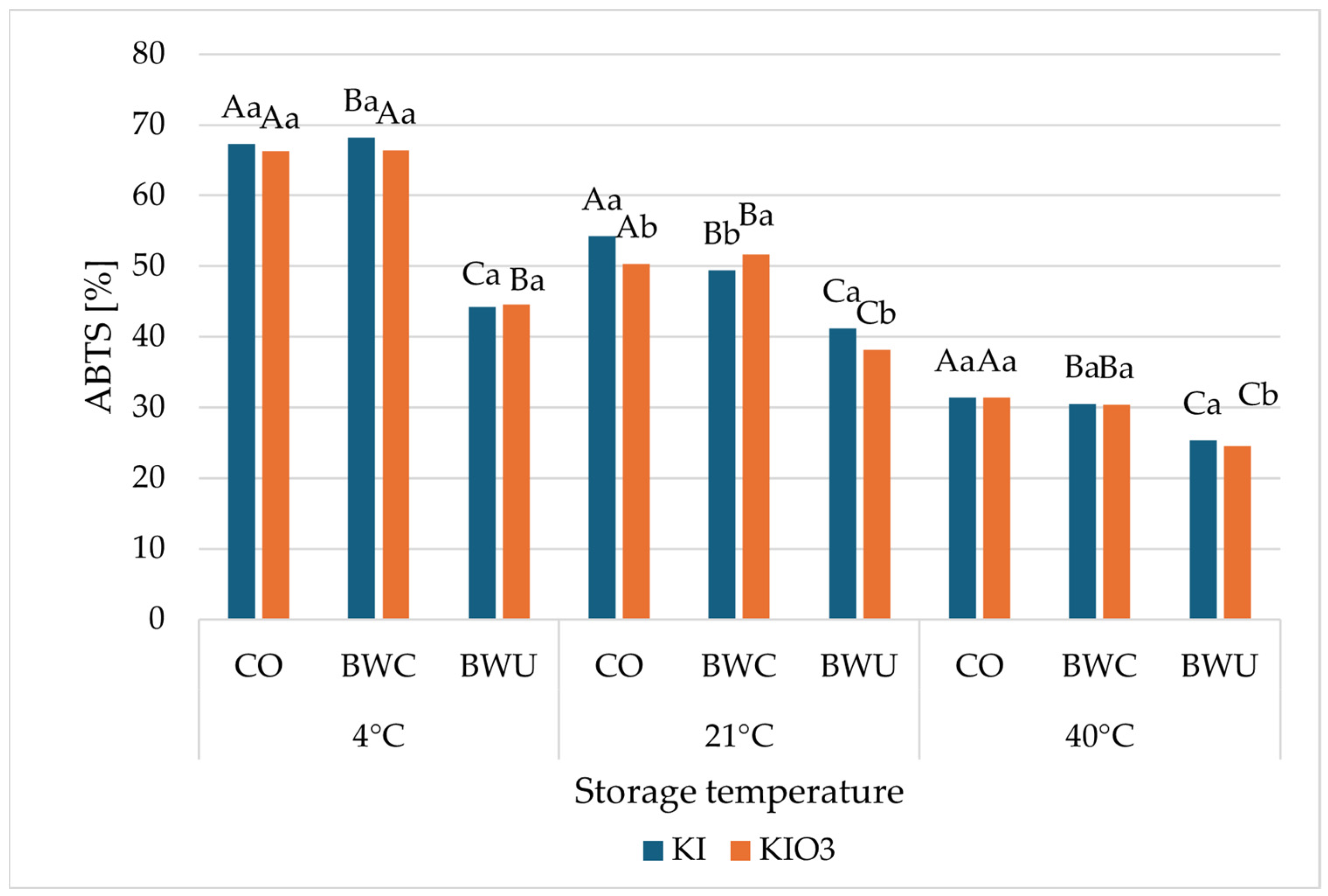

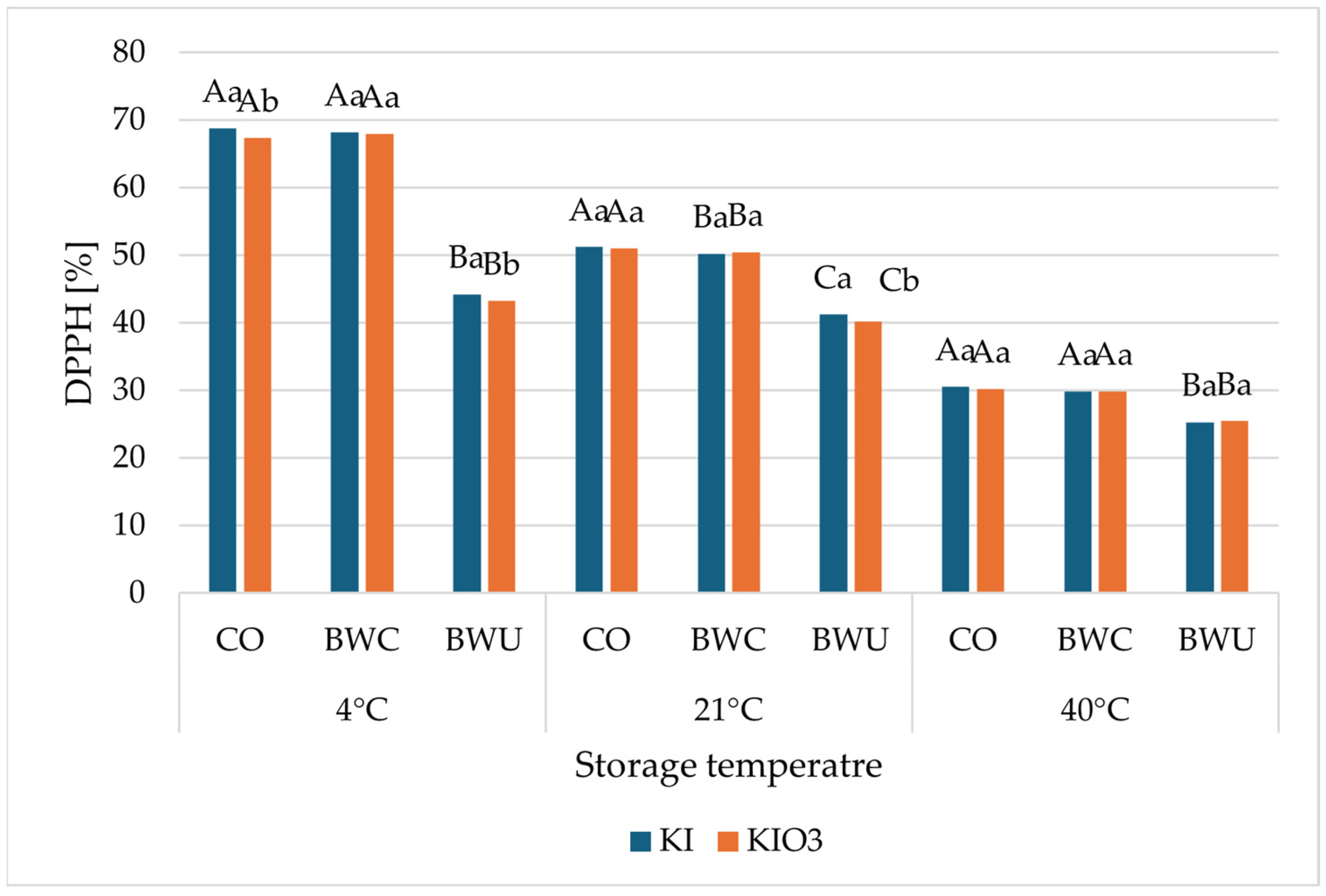

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO | Steamed in a convection oven |

| BWC | Cooking in boiling water covered |

| BWU | Cooking in boiling water uncovered |

| PROG | Progoitrin |

| GB | Glucobrassicin |

| GN | Gluconapin |

| SINIG | Sinigrin |

| IK | Indole-3-carbinol |

Appendix A

| Dynamic of Change in Iodine Content During 90 Days | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature of Storage [°C] | Method of Preparation | T25% [Days] | R2 | RMSE | k | A0 * | T25% [Days] | R2 | RMSE | K * | A0 * |

| KIO3 | KI | ||||||||||

| 4 °C | CO | 150.14 | 0.89 | 0.050 | −0.004 | 11.38 | 96.84 | 0.86 | 0.076 | −0.006 | 14.63 |

| BWC | 174.07 | 0.94 | 0.073 | −0.004 | 12.42 | 118.59 | 0.94 | 0.150 | −0.005 | 10.42 | |

| BWU | 187.56 | 0.90 | 0.034 | −0.004 | 15.93 | 119.75 | 0.88 | 0.045 | −0.005 | 14.45 | |

| 21 °C | CO | 118.81 | 0.86 | 0.085 | −0.005 | 11.12 | 76.36 | 0.79 | 0.114 | −0.006 | 13.12 |

| BWC | 131.78 | 0.87 | 0.135 | −0.005 | 11.96 | 83.97 | 0.83 | 0.184 | −0.006 | 13.78 | |

| BWU | 147.61 | 0.88 | 0.085 | −0.005 | 15.29 | 91.79 | 0.82 | 0.124 | −0.006 | 13.95 | |

| 40 °C | CO | 87.44 | 0.87 | 0.070 | −0.007 | 10.88 | 55.06 | 0.72 | 0.114 | −0.008 | 12.30 |

| BWC | 92.06 | 0.86 | 0.293 | −0.007 | 11.61 | 58.78 | 0.75 | 0.372 | −0.008 | 12.90 | |

| BWU | 98.0 | 0.86 | 0.063 | −0.007 | 14.74 | 64.90 | 0.79 | 0.096 | −0.008 | 13.33 | |

References

- Lisco, G.; De Tullio, A.; Triggiani, D.; Zupo, R.; Giagulli, V.A.; De Pergola, G.; Piazzolla, G.; Guastamacchia, E.; Sabbà, C.; Triggiani, V. Iodine Deficiency and Iodine Prophylaxis: An Overview and Update. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winder, M.; Kosztyła, Z.; Boral, A.; Kocełak, P.; Chudek, J. The Impact of Iodine Concentration Disorders on Health and Cancer. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, M.; Braegger, C.P. The Role of Iodine for Thyroid Function in Lactating Women and Infants. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 469–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuge, R.; Johnson, C.C. Iodine and Human Health, the Role of Environmental Geochemistry and Diet. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 63, 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch-McChesney, A.; Lieberman, H.R. Iodine and Iodine Deficiency: A Comprehensive Review of a Re-Emerging Issue. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Andersson, M. GLOBAL ENDOCRINOLOGY: Global Perspectives in Endocrinology: Coverage of Iodized Salt Programs and Iodine Status in 2020. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 185, R13–R21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Fortification of Food-Grade Salt with Iodine for the Prevention and Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–54.

- Rigutto-Farebrother, J.; Zimmermann, M.B. Salt Reduction and Iodine Fortification Policies Are Compatible: Perspectives for Public Health Advocacy. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinger, E.; Neuenschwander, M.; Koller, A.; Gojda, J.; Kühn, T.; Schwingshackl, L.; Barbaresko, J.; Schlesinger, S. Evidence of a Vegan Diet for Health Benefits and Risks–an Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Observational and Clinical Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 9926–9936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Bailey, R.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; Burton-Freeman, B.; Chen, C.Y.O.; Crowe-White, K.M.; Drewnowski, A.; Hooshmand, S.; Johnson, E.; Lewis, R.; et al. Fruits, Vegetables, and Health: A Comprehensive Narrative, Umbrella Review of the Science and Recommendations for Enhanced Public Policy to Improve Intake. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2174–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, K.; Nugent, A.P.; Woodside, J.V.; Hart, K.H.; Bath, S.C. Iodine and Plant-Based Diets: A Narrative Review and Calculation of Iodine Content. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, L.; Rotondi, M.; Ruggeri, R.M. Modern Challenges of Iodine Nutrition: Vegan and Vegetarian Diets. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1537208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaremba, A.; Gramza-Michałowska, A.; Pal, K.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. The Effect of a Vegan Diet on the Coverage of the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for Iodine among People from Poland. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eveleigh, E.R.; Coneyworth, L.; Welham, S.J.M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Iodine Nutrition in Modern Vegan and Vegetarian Diets. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 130, 1580–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eveleigh, E.R.; Coneyworth, L.J.; Avery, A.; Welham, S.J.M. Vegans, Vegetarians, and Omnivores: How Does Dietary Choice Influence Iodine Intake? A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzepiłko, A.; Zych-Wężyk, I.; Molas, J. Alternative Ways of Enriching the Human Diet with Iodine. J. Pre-Clin. Clin. Res. 2015, 9, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kelly, F.C. Studies on the Stability of Iodine Compounds in Iodized Salt. Bull. World Health Organ. 1953, 9, 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Pahuja, D.N.; Rajan, M.G.; Borkar, A.V.; Samuel, A.M. Potassium Iodate and Its Comparison to Potassium Iodide As a Blocker of 131I Uptake by the Thyroid in Rats. Health Phys. 1993, 65, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, A.; Szymandera-Buszka, K.E. The Effect Of Iodine Fortification On—The Antioxidant Activity Of Carrots And Cauliflower. J. Res. Appl. Agric. Eng. 2024, 23, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremba, A.; Hęś, M.; Jędrusek-Golińska, A.; Przeor, M.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. The Antioxidant Properties of Selected Varieties of Pumpkin Fortified with Iodine in the Form of Potassium Iodide and Potassium Iodate. Foods 2023, 12, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winger, R.J.; König, J.; House, D.A. Technological Issues Associated with Iodine Fortification of Foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwan, P.; Stępniak, J.; Karbownik-Lewińska, M. Pro-Oxidative Effect of KIO3 and Protective Effect of Melatonin in the Thyroid—Comparison to Other Tissues. Life 2021, 11, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouad, A.A.; Rehab, A.F.M. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Fresh and Processed White Cauliflower. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 367819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panduang, T.; Phucharoenrak, P.; Karnpanit, W.; Trachootham, D. Cooking Methods for Preserving Isothiocyanates and Reducing Goitrin in Brassica Vegetables. Foods 2023, 12, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drabińska, N.; Jeż, M.; Nogueira, M. Variation in the Accumulation of Phytochemicals and Their Bioactive Properties among the Aerial Parts of Cauliflower. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B. The Remarkable Impact of Iodisation Programmes on Global Public Health. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgin, N.; El, S.N. Effects of Cooking on in Vitro Sinigrin Bioaccessibility, Total Phenols, Antioxidant and Antimutagenic Activity of Cauliflower (Brassica oleraceae L. var. Botrytis). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 37, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.S. Effect of Cooking Method on Antioxidant Compound Contents in Cauliflower. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 24, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Dalmazi, G.; Giuliani, C. Plant Constituents and Thyroid: A Revision of the Main Phytochemicals That Interfere with Thyroid Function. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 152, 112158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanty, A.; Grudzińska, M.; Paździora, W.; Służały, P.; Paśko, P. Do Brassica Vegetables Affect Thyroid Function?—A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwata, E.T.; Onipe, O.O.; Naicker, O.; Tsakani, M.M.; Mashifane, D.C. A Survey of Goitrogenic Compounds in Selected Millets and Cruciferous Vegetables. In Food Security and Nutrition: Utilizing Undervalued Food Plants; Bvenura, C., Kambizi, L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mezdoud, A.; Agli, S.; Agli, A.N.; Bahchachi, N.; Oulamara, H. Consumption of Cruciferous Foods, Ingestion of Glucosinolates and Goiter in a Region of Eastern Algeria. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 10, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobiecka, D.P.; Moskwa, J.; Markiewicz-żukowska, R.; Socha, K.; Naliwajko, S.K. Cruciferous Vegetables in Hashimoto’s Disease Diet. Postep. Biochem. 2024, 70, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapusta-Duch, J.; Szelag-Sikora, A.; Sikora, J.; Niemiec, M.; Gródek-Szostak, Z.; Kuboń, M.; Leszczyńska, T.; Borczak, B. Health-Promoting Properties of Fresh and Processed Purple Cauliflower. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousumi, J.S.; Sharmin, A.S.; Tusar, K.R.; Keya, A.; Shishir, R.; Mostofa, J.D.; Masum, A.; Nesar, U. Nutrition and Antioxidant Potential of Three Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L. var. Botrytis) Cultivars Cultivated in Southern Part of Bangladesh. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 13, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Dou, J.; Lv, J.; Jin, N.; Jin, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Tang, Z.; Yu, J. A Comparative Study on the Nutrients, Mineral Elements, and Antioxidant Compounds in Different Types of Cruciferous Vegetables. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, Q.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Sun, X.; Min, L.; Liu, Z.; Ma, W.; Zhao, J. Brassica Vegetables—An Undervalued Nutritional Goldmine. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremba, A.; Waszkowiak, K.; Kmiecik, D.; Jędrusek-Golińska, A.; Jarzębski, M.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. The Selection of the Optimal Impregnation Conditions of Vegetable Matrices with Iodine. Molecules 2022, 27, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, D.; Wirth, F.; Wagner, H. Iodine Determination in Iodized Meat Products. Fleischwirtschaft 1993, 73, 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- Moxon, R.E.; Dixon, E.J. Semi-Automatic Method for the Determination of Total Iodine in Food. Analyst 1980, 105, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszkowiak, K.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. The Application of Wheat Fibre and Soy Isolate Impregnated with Iodine Salts to Fortify Processed Meats. Meat Sci. 2008, 80, 1340–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2483:1973; Sodium Chloride for Industrial Use—Determination of the Loss of Mass at 110 Degrees C (Reviewed and Confirmed in 2018). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Iswaldi, I.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Profiling of Phenolic and Other Polar Compounds in Zucchini (Cucurbita pepo L.) by Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuutila, M.A.; Puupponen-Pimia, R.; Aarni, M.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.-M. Comparison of Antioxidant Activities of Onion and Garlic Extracts by Inhibition of Lipid Peroxidation and Radical Scavenging Activity. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-L.; Hsu, H.-F. Flavonoid Content of Several Vegetables and Their Antioxidant Activity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying An Improved Abts Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymandera-Buszka, K.; Waszkowiak, K.; Kaczmarek, A.; Zaremba, A. Wheat Dietary Fibre and Soy Protein as New Carriers of Iodine Compounds for Food Fortification—The Effect of Storage Conditions on the Stability of Potassium Iodide and Potassium Iodate. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 137, 110424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lena, J.; Maisam, S.; Zaid, A. Study of the Effect of Storage Conditions on Stability of Iodine in Iodized Table Salt. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2015, 7, 701–706. [Google Scholar]

- Diosady, L.L.; Alberti, J.O.; Venkatesh Mannar, M.G.; Fitzgerald, S. Stability of Iodine in Iodized Salt Used for Correction of Iodine-Deficiency Disorders. II. Food Nutr. Bull. 1998, 19, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszkowiak, K.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. Effect of Storage Conditions on Potassium Iodide Stability in Iodised Table Salt and Collagen Preparations. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, S.H.; Khalilpour, A.; Amouei, A.; Rezapour, M.; Tabarinia, H. Stability of Iodine in Iodized Salt Against Heat, Light and Humidity. Int. J. Health Life Sci. 2020, 6, e100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Raghuvanshi, R.S. Effect of Different Cooking Methods on Iodine Losses. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jankowska, A.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. Antioxidant Properties of Beetroot Fortified with Iodine. J. Res. Appl. Agric. Eng. 2023, 68, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Pérez, A.; Núñez-Gómez, V.; Baenas, N.; Di Pede, G.; Achour, M.; Manach, C.; Mena, P.; Del Rio, D.; García-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A.; et al. Systematic Review on the Metabolic Interest of Glucosinolates and Their Bioactive Derivatives for Human Health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Lombardo, M.; D’Amato, A.; Karav, S.; Tripodi, G.; Aiello, G. Glucosinolates in Human Health: Metabolic Pathways, Bioavailability, and Potential in Chronic Disease Prevention. Foods 2025, 14, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melim, C.; Lauro, M.R.; Pires, I.M.; Oliveira, P.J.; Cabral, C. The Role of Glucosinolates from Cruciferous Vegetables (Brassicaceae) in Gastrointestinal Cancers: From Prevention to Therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felker, P.; Bunch, R.; Leung, A.M. Concentrations of Thiocyanate and Goitrin in Human Plasma, Their Precursor Concentrations in Brassica Vegetables, and Associated Potential Risk for Hypothyroidism. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska, A.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. Nutritional Adequacy of Flour Product Enrichment with Iodine-Fortified Plant-Based Products. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymandera-Buszka, K.; Jankowska, A.; Jędrusek-Golińska, A. Mapping Consumer Preference for Vegan and Omnivorous Diets for the Sensory Attributes of Flour Products with Iodine-Fortified Plant-Based Ingredients. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobosy, P.; Nguyen, H.T.P.; Záray, G.; Streli, C.; Ingerle, D.; Ziegler, P.; Radtke, M.; Buzanich, A.G.; Endrédi, A.; Fodor, F. Effect of Iodine Species on Biofortification of Iodine in Cabbage Plants Cultivated in Hydroponic Cultures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassano, S.; Di Gaudio, F.; Sabatino, L.; Caldarella, R.; De Pasquale, C.; Di Rosa, L.; Nuzzo, D.; Picone, P.; Vasto, S. Biofortification: Effect of Iodine Fortified Food in the Healthy Population, Double-Arm Nutritional Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 871638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, M.; Formisano, L.; El-Nakhel, C.; Zarrelli, A.; Giordano, M.; De Pascale, S.; Kyriacou, M.; Rouphael, Y. Iodine Biofortification of Four Microgreens Species and Its Implications for Mineral Composition and Potential Contribution to the Recommended Dietary Intake of Iodine. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzemińska, J.; Kapusta-Duch, J.; Smoleń, S.; Kowalska, I.; Słupski, J.; Skoczeń-Słupska, R.; Krawczyk, K.; Waśniowska, J.; Koronowicz, A. Iodine Enriched Kale (Brassica oleracea var. Sabellica L.)—The Influence of Heat Treatments on Its Iodine Content, Basic Composition and Antioxidative Properties. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waśniowska, J.; Leszczyńska, T.; Kopeć, A.; Piątkowska, E.; Smoleń, S.; Krzemińska, J.; Kowalska, I.; Słupski, J.; Piasna-Słupecka, E.; Krawczyk, K.; et al. Curly Kale (Brassica oleracea var. Sabellica L.) Biofortified with 5,7-Diiodo-8-Quinolinol: The Influence of Heat Treatment on Iodine Level, Macronutrient Composition and Antioxidant Content. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridullah, F.; Shabbir, H.; Iqbal, A.; Bacha, A.-U.-R.; Arifeen, A.; Bhatti, Z.A.; Mujtaba, G. Iodine Supplementation through Its Biofortification in Brassica Species Depending on the Type of Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 37208–37218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Iodine Form | Method of Preparation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | BWC | BWU | ||||

| % | Standard Deviation | % | Standard Deviation | % | Standard Deviation | |

| After drying | ||||||

| 4 °C | ||||||

| KI | 86.25 bC* | 0.16 | 91.25 bB | 0.22 | 93.05 bA | 0.11 |

| KIO3 | 90.85 aC | 0.21 | 93.36 aB | 0.21 | 95.98 aA | 0.14 |

| After storage (90 days) | ||||||

| 4 °C | ||||||

| KI | 82.92 bA* | 0.12 | 80.70 bB | 0.22 | 83.39 bA | 0.11 |

| KIO3 | 84.32 aC | 0.11 | 86.02 aB | 0.21 | 87.92 aA | 0.14 |

| 21 °C | ||||||

| KI | 78.56 bA* | 0.11 | 77.06 bB | 0.20 | 78.61 bA | 0.11 |

| KIO3 | 80.28 aC | 0.14 | 82.14 aB | 0.21 | 83.96 aA | 0.14 |

| 40 °C | ||||||

| KI | 70.49 bC* | 0.12 | 71.76 bB | 0.19 | 73.02 bA | 0.11 |

| KIO3 | 74.04 aC | 0.13 | 75.76 aB | 0.21 | 76.82 aA | 0.14 |

| Predictors | SS | df | MSE | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodine form | 67.10 | 1 | 67.10 | 2.93 | 0.11 |

| KI | |||||

| Heat treatment | 5.06 | 2 | 2.53 | 0.09 | 0.92 |

| Storage temperature | 170.03 | 2 | 85.01 | 57.44 | 0.00 |

| KIO3 | |||||

| Heat treatment | 16.89 | 2 | 8.44 | 0.30 | 0.75 |

| Storage temperature | 170.24 | 2 | 85.12 | 29.69 | 0.00 |

| Type of Phenolic Compounds | Iodine Form and Temperature of Storage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 °C | 21 °C | 40 °C | ||||

| KI | KIO3 | KI | KIO3 | KI | KIO3 | |

| After storage (30 days) | ||||||

| PG | −0.796 *** | −1.000 **** | −0.705 *** | −0.978 **** | −0.726 *** | −0.972 **** |

| GB | −0.314 * | −0.874 *** | 0.132 NS | −0.561 ** | −0.764 *** | −0.390 * |

| GN | 0.434 ** | −0.498 ** | 0.150 NS | −0.070 NS | 0.079 NS | −0.750 *** |

| SG | 0.877 *** | 0.998 **** | 0.755 *** | 0.633 ** | −0.718 *** | 0.791 *** |

| IK | 0.644 ** | 0.990 **** | 0.870 *** | 0.978 **** | 0.779 *** | 0.922 **** |

| After storage (60 days) | ||||||

| PG | 0.870 *** | −0.827 *** | −0.949 **** | −0.954 **** | −0.969 **** | −0.896 *** |

| GB | −0.702 *** | −0.755 *** | −0.374 * | −0.481 ** | −0.407 ** | −0.845 *** |

| GN | −0.373 * | 0.079 NS | −0.722 *** | 0.998 **** | −0.622 ** | 0.572 ** |

| SG | 0.912 **** | 0.976 **** | 0.755 *** | 0.994 **** | 0.990 **** | 0.999 **** |

| IK | 0.872 *** | 0.917 **** | 0.956 **** | 0.908 **** | 0.822 *** | 0.995 **** |

| After storage (90 days) | ||||||

| PG | −0.830 *** | −0.756 *** | −0.956 **** | −0.984 **** | −0.987 **** | −0.878 *** |

| GB | −0.999 **** | −0.439 ** | −0.709 *** | 0.080 NS | −0.574 ** | −0.400 ** |

| GN | −0.168 NS | 0.826 *** | −0.603 ** | 0.822 *** | −0.809 *** | −0.739 ** |

| SG | 0.465 ** | 0.892 *** | 0.996 **** | 0.995 **** | 0.953 **** | 0.648 ** |

| IK | 0.990 **** | 0.914 **** | 0.904 **** | 0.835 *** | 0.890 *** | 0.675 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jankowska, A.; Przeor, M.; Waszkowiak, K.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. Influence of Heat Treatment Prior to Fortification on Goitrogenic Compounds, Iodine Stability and Antioxidant Activity in Cauliflower. Foods 2026, 15, 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020315

Jankowska A, Przeor M, Waszkowiak K, Szymandera-Buszka K. Influence of Heat Treatment Prior to Fortification on Goitrogenic Compounds, Iodine Stability and Antioxidant Activity in Cauliflower. Foods. 2026; 15(2):315. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020315

Chicago/Turabian StyleJankowska, Agata, Monika Przeor, Katarzyna Waszkowiak, and Krystyna Szymandera-Buszka. 2026. "Influence of Heat Treatment Prior to Fortification on Goitrogenic Compounds, Iodine Stability and Antioxidant Activity in Cauliflower" Foods 15, no. 2: 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020315

APA StyleJankowska, A., Przeor, M., Waszkowiak, K., & Szymandera-Buszka, K. (2026). Influence of Heat Treatment Prior to Fortification on Goitrogenic Compounds, Iodine Stability and Antioxidant Activity in Cauliflower. Foods, 15(2), 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020315