Maca (Lepidium meyenii) as a Functional Food and Dietary Supplement: A Review on Analytical Studies

Abstract

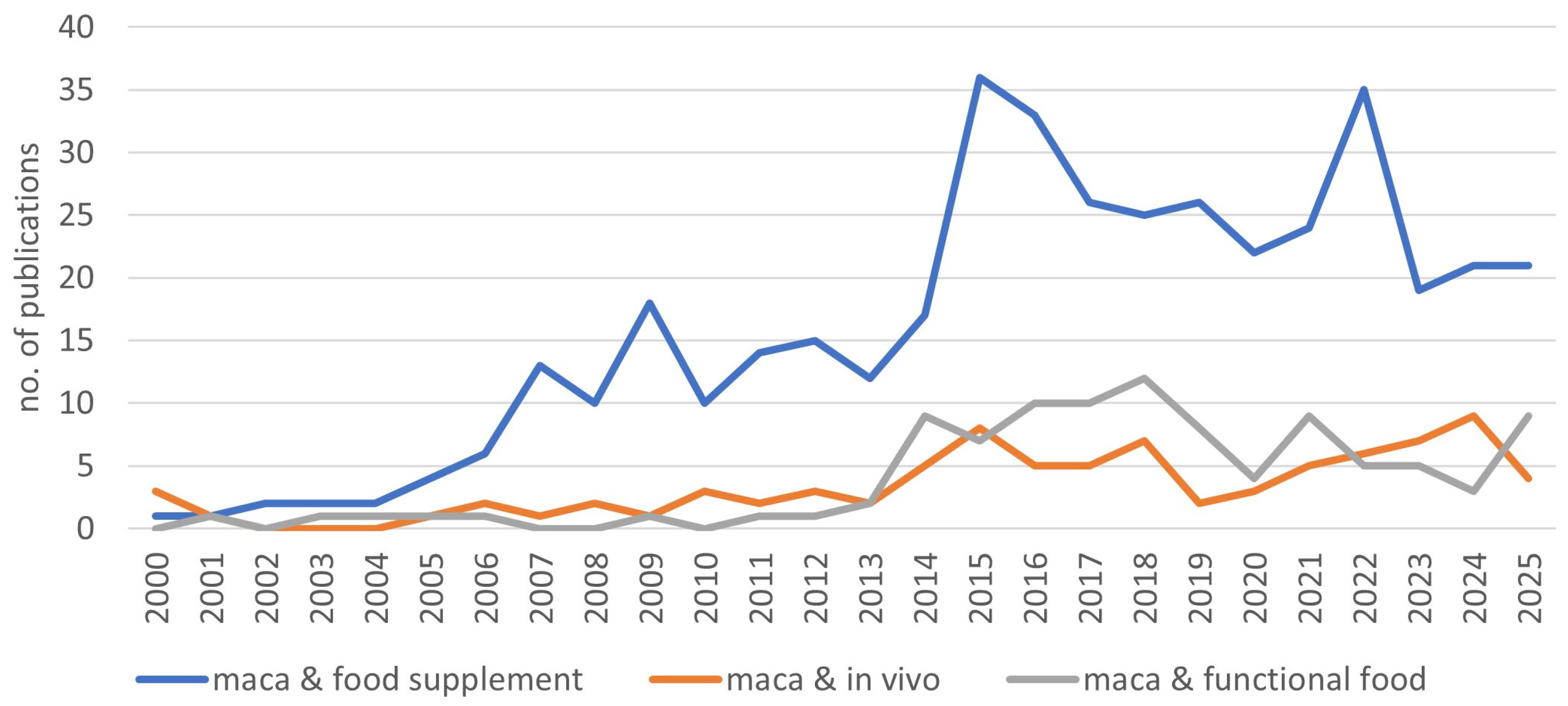

1. Introduction

2. Chemical Constituents

2.1. Macamides and Macaenes

2.2. Sulfur-Containing Compounds: Glucosinolates, Thiohydantoins, and Related Compounds

2.3. Alkaloids

2.4. Miscellaneous Compounds

3. Analytical Techniques

3.1. Qualitative Analysis

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

| Study No. | Sample | Extraction Solvent | Extraction Method | Quantitation Method | Conditions | Investigated Compounds | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-A | Dried and powdered hypocotyl | 70% Aqueous ethanol | n. d. | HPLC-UV 1 (235 nm) | Bondapak C18, H2O + 0.1% TEA/MeOH, gradient, 70 min, 4 mL/min, 2 | Glucosinolates (28, 29, 33, 38) | [26] |

| I-B | n-Hexane | n. d. | GC-MS 1 (QqQ) | DB-5 column, helium, gradient, 57 min, 1 mL/min | Isothiocyanates | ||

| II | Dried hypocotyl, dietary supplements | Methanol | Sonication (10 min) | HPLC-UV (210, 280 nm) | Synergi Max-RP (C12), H2O + 0.025 TFA/ACN + 0.025% TFA, gradient, 35 min, 40 °C, 1.0 mL/min | Macamides (1, 8), macaene (22), fatty acids (26, 27) | [27] |

| III | Dried and powdered hypocotyl, dietary supplements | Petroleum ether | Shaking (24 h, 150 rpm) | HPLC-UV (210 nm) | Zorbax XDB C18, H2O + 0.005 TFA/ACN + 0.005% TFA, gradient, 30 min, 40 °C, 0.8 mL/min | Macamide (1) | [19] |

| IV | Dried and powdered red hypocotyls | Water | Decoction (60 min) | HPLC-UV (230 nm) | C18 column, H2O/20% aqueous ACN, gradient, 31 min, 1.5 mL/min, 2 | Glucosinolate (28) | [58] |

| V | Dried and powdered hypocotyls of different color | Methanol | Sonication (20 min) | HPLC-UV (210, 280 nm) | Synergi Max-RP (C12), H2O + 0.025 TFA/ACN + 0.025% TFA, gradient, 60 min, 40 °C, 1.0 mL/min | Macamides (1, 8, 9), macaene (22) | [13] |

| VI | Dried and powdered hypocotyls of different color and origin | Petroleum ether | Ultrasonication | HPLC-UV (210 nm) | Zorbax XDB C18, H2O/ACN, gradient, 30 min, 40 °C, 0.8 mL/min | Macamides (1–7, 14–17), fatty acids (26, 27) | [56] |

| VII | Powdered hypocotyls of different origin | Methanol | Ultrasonication (30 min) | UHPLC-MS (ESI, QqQ) | Thermo Hypersil-Gold C18, H2O + 0.2% FA/ACN, gradient, 15 min, 30 °C, 0.3 mL/min | Macamides (1, 14), glucosinolates (28–30), alkaloid (75) | [54] |

| VIII | Dried and powdered hypocotyls | Petroleum ether | Ultrasonication (50 °C, 15 min) | HPLC-MS (QTOF) | XTerra C18, H2O/ACN/FA, isocratic, 35 min, 30 °C, 0.6 mL/min | Macamides (1, 4–7, 15–16) | [59] |

| IX | Dried and powdered hypocotyls | Methanol | Ultrasonication (40 °C, 60 min) | HPLC-UV (210, 280 nm) | Zorbax XBD-C18, H2O/ACN + 0.005% TFA, gradient, 45 min, 40 °C, 1 mL/min | Macamides (1, 6, 7, 11, 12), macaenes (23, 24) | [23] |

| X | Dried and powdered hypocotyls | Ethyl acetate/methanol (2:1) | Ultrasonication (60 min), column chromatography | 1H qNMR | 600 MHz, cryoprobe, CDCl3 | Total macamides | [57] |

| XI | Hypocotyls dried in different conditions | Methanol | Ultrasonication (40 °C, 60 min) | HPLC-UV (210, 280 nm) | Zorbax XDB C18, H2O/ACN + 0.005% TFA, gradient, 45 min, 40 °C, 1 mL/min | Macamides (1, 6, 7, 11, 12), macaenes (23–25) | [55] |

| XII | Dietary supplements | 70% Aqueous methanol | Sonication (10 min) | HPLC-UV (227 nm) | Luna C18(2), H2O + 0.1% TFA/ACN + 0.1% TFA, gradient, 30 min, 23 °C, 1.0 mL/min | Glucosinolates (28–31) | [32] |

| XIII-A | Dried and powdered hypocotyls | 75% Aqueous methanol | Ultrasonication (30 min) | UHPLC-UV (210 nm) | Acquity HSST3 column (C18), 10 mM aqueous (NH4)3PO3/ACN, gradient, 14 min, 35 °C, 0.3 mL/min | Macamides (1, 3, 5–7, 14, 16, 17), glucosinolates (28, 29) | [30] |

| XIII-B | Ethyl acetate | Ultrasonication (60 min) | GC-MS (EI) | SH-Rxi-1 MS column, helium, gradient, 27 min, 1 mL/min | Isothiocyanates | ||

| XIV | Powdered hypocotyls | Methanol | n. d. | UHPLC-MS (ESI, TOF) | AcclaimTM RSLC 120C18, H2O/75% aqueous ACN + 0.05% FA, isocratic, 9 min, 35 °C, 0.4 mL/min | Macamides (1, 5–7, 16), fatty acids (26, 27) | [29] |

| XV | Dried hypocotyls | 50% Aqueous ethanol | Ultrasonication (3 × 30 min) | HPLC-MS (ESI-QTOF) | Zorbax Eclipse Puls RP-18, H2O + 0.1% FA/ACN + 0.1% FA, gradient, 45 min, 0.2 mL/min, 2 | Glucosinolate (28) | [60] |

| XVI | Dried and powdered hypocotyls | Deep eutectic solvents | Ultrasonication (40 °C, 30 min) | HPLC-UV (210 nm) | Zorbax XDB C18, H2O/ACN, gradient, 30 min, 40 °C, 0.8 mL/min | Macamides (1, 6, 7, 16, 17) | [61] |

| XVII | Powdered hypocotyls, dietary supplements | 75% Methanol | Sonication (30 min) | UHPLC-MS (ESI, QqQ) | Acquity BEH C18, H2O + 0.1% FA/ACN + 0.1% FA, gradient, 10 min, 40 °C, 0.5 mL/min | Alkaloids (73, 75, 80, 90–94, 97, 98) | [3] |

3.3. Chemometric Methods Applied for Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses

4. Maca Ecotypes and Geographical Differences

5. Potential Toxicity, Limitations, and Problems of Adulteration

6. Methods of Literature Search

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DAD | Diode array detection |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| HCA | Hierarchical cluster analysis |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| IR | Infrared spectroscopy |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PLS | Partial least squares regression |

| TLC | Thin layer chromatography |

| U(H)PLC | Ultra-(high)performance liquid chromatography |

References

- Chen, R.; Wei, J.; Gao, Y. A review of the study of active components and their pharmacology value in Lepidium meyenii (Maca). Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 6706–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, G.F. Ethnobiology and ethnopharmacology of Lepidium meyenii (Maca), a plant from the Peruvian highlands. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 2012, 193496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, N.T.; Foubert, K.; Theunis, M.; Naessens, T.; Bozdag, M.; Van Der Veken, P.; Pieters, L.; Tuenter, E. UPLC-TQD-MS/MS method validation for quality control of alkaloid content in Lepidium meyenii (Maca)-containing food and dietary supplements. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 15971–15981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Leitao Peres, N.; Cabrera Parra Bortoluzzi, L.; Medeiros Marques, L.L.; Formigoni, M.; Fuchs, R.H.B.; Droval, A.A.; Reitz Cardoso, F.A. Medicinal effects of Peruvian maca (Lepidium meyenii): A review. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Das, M. Functional foods: An overview. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 20, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.K.; Sharma, V.; Krishna, G. Superfoods in drug discovery: Nutrient profiles and their emerging health benefits. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2025, 22, e15701638355532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damián, M.R.; Cortes-Perez, N.G.; Quintana, E.T.; Ortiz-Moreno, A.; Garfias Noguez, C.; Cruceño-Casarrubias, C.E.; Sánchez Pardo, M.E.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G. Functional foods, nutraceuticals and probiotics: A focus on human health. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.; Wilairatana, P.; Saqib, F.; Nasir, B.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M.F.; Iqbal, A.; Naz, R.; Mubarak, M.S. Plant polyphenols and their potential benefits on cardiovascular health: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Lone, A.N.; Khan, M.S.; Virani, S.S.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Nasir, K.; Miller, M.; Michos, E.D.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Boden, W.E.; et al. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beharry, S.; Heinrich, M. Is the hype around the reproductive health claims of maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) justified? J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 211, 126–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa Del Carpio, N.; Alvarado-Corella, D.; Quinones-Laveriano, D.M.; Araya-Sibaja, A.; Vega-Baudrit, J.; Monagas-Juan, M.; Navarro-Hoyos, M.; Villar-Lopez, M. Exploring the chemical and pharmacological variability of Lepidium meyenii: A comprehensive review of the effects of maca. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1360422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.V.; Ribeiro, P.R. Structural diversity, biosynthetic aspects, and LC-HRMS data compilation for the identification of bioactive compounds of Lepidium meyenii. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, C.; Diaz Grados, D.A.; Avula, B.; Khan, I.A.; Mayer, A.C.; Ponce Aguirre, D.D.; Manrique, I.; Kreuzer, M. Influence of colour type and previous cultivation on secondary metabolites in hypocotyls and leaves of maca (Lepidium meyenii Walpers). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.J.; Zhao, Q.S.; Liu, Y.L.; Zha, S.H.; Zhao, B. Identification of maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) and its adulterants by a DNA-barcoding approach based on the ITS sequence. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2015, 13, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhou, H. Combining targeted metabolites analysis and transcriptomics to reveal chemical composition difference and underlying transcriptional regulation in Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) ecotypes. Genes 2018, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Avula, B.; Chan, M.; Clement, C.; Kreuzer, M.; Khan, I.A. Metabolomic differentiation of maca (Lepidium meyenii) accessions cultivated under different conditions using NMR and chemometric analysis. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Sun, X.; Gao, Y.; Chen, R. Differentiation of Lepidium meyenii (Maca) from different origins by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry with principal component analysis. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 16493–16500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, A.; Migliuolo, G.; Rastrelli, L.; Saturnino, P.; Schettino, O. Chemical composition of Lepidium meyenii. Food Chem. 1994, 49, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollom, M.M.; Villinski, J.R.; McPhail, K.L.; Craker, L.E.; Gafner, S. Analysis of macamides in samples of maca (Lepidium meyenii) by HPLC-UV-MS/MS. Phytochem. Anal. 2005, 16, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.L.; Yan, H.; Xu, H.D.; Muhammad, N.; Yan, W.D. Preparation from Lepidium meyenii Walpers using high-speed countercurrent chromatography and thermal stability of macamides in air at various temperatures. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 164, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Zhao, J.; Dunbar, D.C.; Khan, I.A. Constituents of Lepidium meyenii ‘maca’. Phytochemistry 2002, 59, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Muhammad, I.; Dunbar, D.C.; Mustafa, J.; Khan, I.A. New alkamides from maca (Lepidium meyenii). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Deng, J.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, C. Simultaneous determination of macaenes and macamides in maca using an HPLC method and analysis using a chemometric method (HCA) to distinguish maca origin. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2019, 29, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chain, F.E.; Grau, A.; Martins, J.C.; Catalán, C.A.N. Macamides from wild ‘Maca’, Lepidium meyenii Walpers (Brassicaceae). Phytochem. Lett. 2014, 8, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.Q.; Ma, Z.H.; Yang, Q.F.; Sun, Y.Q.; Zhang, R.Q.; Wu, R.F.; Ren, X.; Mu, L.J.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Zhou, M. Isolation and synthesis of a new benzylated alkamide from the roots of Lepidium meyenii. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 2731–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacente, S.; Carbone, V.; Plaza, A.; Zampelli, A.; Pizza, C. Investigation of the tuber constituents of maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5621–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzera, M.; Zhao, J.; Muhammad, I.; Khan, I.A. Chemical profiling and standardization of Lepidium meyenii (Maca) by reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, B.; Hua, H.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yao, W.; Qian, H. Macamides: A review of structures, isolation, therapeutics and prospects. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Wei, J.; Gao, Y.; Chen, R. Antioxidant and antitumoral activities of isolated macamide and macaene fractions from Lepidium meyenii (maca). Talanta 2021, 221, 121635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Q.; Qiao, S.Y.; Wang, Z.Q.; Cui, M.Y.; Tan, D.P.; Feng, H.; Mei, X.S.; Li, G.; Cheng, L. Quantitative determination of 15 active components in Lepidium meyenii with UHPLC-PDA and GC-MS. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2021, 2021, 6333989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yábar, E.; Pedreschi, R.; Chirinos, R.; Campos, D. Glucosinolate content and myrosinase activity evolution in three maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) ecotypes during preharvest, harvest and postharvest drying. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Monagas, M.J.; Kassymbek, Z.K.; Belsky, J.L. Controlling the quality of maca (Lepidium meyenii) dietary supplements: Development of compendial procedures for the determination of intact glucosinolates in maca root powder products. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 199, 114063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ammermann, U.; Quirós, C.F. Glucosinolate contents in maca (Lepidium peruvianum Chacón) seeds, sprouts, mature plants and several derived commercial products. Econ. Bot. 2001, 55, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-Y.; Qin, X.-J.; Peng, X.-R.; Wang, X.; Tian, X.-X.; Li, Z.-R.; Qiu, M.-H. Macathiohydantoins B–K, novel thiohydantoin derivatives from Lepidium meyenii. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 4392–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Yan, H.; Peng, X.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, M. Macathiohydantoin L, a novel thiohydantoin bearing a thioxohexahydroimidazo [1,5-a] pyridine moiety from maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.). Molecules 2021, 26, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.-C.; Wang, X.-S.; Liao, Y.-J.; Qiu, S.-Y.; Fang, H.-X.; Chen, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-M.; Zhou, M. Macathiohydantoins P–R, three new thiohydantoin derivatives from maca (Lepidium meyenii). Phytochem. Lett. 2022, 51, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-Y.; Qin, X.-J.; Shao, L.-D.; Peng, X.-R.; Li, L.; Yang, H.; Qiu, M.-H. Macahydantoins A and B, two new thiohydantoin derivatives from maca (Lepidium meyenii): Structural elucidation and concise synthesis of macahydantoin A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 1684–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Ma, H.Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Yang, G.Y.; Du, G.; Ye, Y.Q.; Li, G.P.; Hu, Q.F. (+)-Meyeniins A-C, novel hexahydroimidazo[1,5-c]thiazole derivatives from the tubers of Lepidium meyenii: Complete structural elucidation by biomimetic synthesis and racemic crystallization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 1887–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-X.; Li, J.; Liao, C.-J.; Yang, F.-W.; Geng, H.-C.; Zhou, M. New thiohydantoin derivatives from the roots of Lepidium meyenii. Phytochem. Lett. 2025, 67, 102964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.-R.; Zhang, R.-R.; Liu, J.-H.; Li, Z.-R.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M.-H. Lepithiohydimerins A—D: Four pairs of neuroprotective thiohydantoin dimers bearing a disulfide bond from maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.). Chin. J. Chem. 2021, 39, 2738–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarigul, S.; Dogan, I. Atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral thiohydantoin derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 5895–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Peng, X.; Yu, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M. Hydantoin and thioamide analogues from Lepidium meyenii. Phytochem. Lett. 2018, 25, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, R.-Q.; Chen, Y.-J.; Liao, L.-M.; Sun, Y.-Q.; Ma, Z.-H.; Yang, Q.-F.; Li, P.; Ye, Y.-Q.; Hu, Q.-F. Three new pyrrole alkaloids from the roots of Lepidium meyenii. Phytochem. Lett. 2018, 23, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.T.N.; Van Roy, E.; Dendooven, E.; Peeters, L.; Theunis, M.; Foubert, K.; Pieters, L.; Tuenter, E. Alkaloids from Lepidium meyenii (Maca), structural revision of macaridine and UPLC-MS/MS feature-based molecular networking. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purnomo, K.A.; Korinek, M.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Hu, H.-C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Backlund, A.; Hwang, T.-L.; Chen, B.-H.; Wang, S.-W.; Wu, C.-C.; et al. Decoding multiple biofunctions of maca on its anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, and pro-angiogenic activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11856–11866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.; Zhang, R.R.; Peng, X.R.; Ding, Z.T.; Qiu, M.H. Lepipyrrolins A-B, two new dimeric pyrrole 2-carbaldehyde alkaloids from the tubers of Lepidium meyenii. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 112, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Zheng, B.L.; He, K.; Zheng, Q.Y. Imidazole alkaloids from Lepidium meyenii. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1101–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Chen, X.; Dai, P.; Yu, L. Lepidiline C and D: Two new imidazole alkaloids from Lepidium meyenii Walpers (Brassicaceae) roots. Phytochem. Lett. 2016, 17, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, G.F.; Gonzales-Castaneda, C. The methyltetrahydro-β-carbolines in Maca (Lepidium meyenii). Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 6, 315–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herraiz, T. 1-Methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline-3-carboxylic acid and 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-β-carboline-3-carboxylic acid in fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 4883–4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Ren, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Min, T.; Lai, F.; Wu, H. Structural characterization of a novel polysaccharide from Lepidium meyenii (Maca) and analysis of its regulatory function in macrophage polarization in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.Y.; Wang, D.W.; Yan, Y.M.; Cheng, Y.X. Lignans from Lepidium meyenii and their anti-inflammatory activities. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, N.; He, K.; Roller, M.; Lai, C.S.; Bai, L.; Pan, M.H. Flavonolignans and other constituents from Lepidium meyenii with activities in anti-inflammation and human cancer cell lines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 2458–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, P.; Brantner, A.; Wang, H.; Shu, X.; Yang, J.; Si, N.; Han, L.; Zhao, H.; Bian, B. Chemical profiling analysis of maca using UHPLC-ESI-Orbitrap MS coupled with UHPLC-ESI-QqQ MS and the neuroprotective study on its active ingredients. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Deng, J.; Pan, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhu, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, B.; et al. Comprehensive profiling of macamides and fatty acid derivatives in maca with different postharvest drying processes using UPLC-QTOF-MS. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24484–24492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Li, K.K.; Pubu, D.; Jiang, S.P.; Chen, B.; Chen, L.R.; Yang, Z.; Ma, C.; Gong, X.J. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction, HPLC and UHPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS/MS analysis of main macamides and macaenes from maca (cultivars of Lepidium meyenii Walp). Molecules 2017, 22, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.-R.; Huang, Y.-J.; Liu, J.-H.; Zhang, R.-R.; Li, Z.-R.; Zhou, L.; Qiu, M.-H. 1H qNMR-based quantitative analysis of total macamides in five maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) dried naturally. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 100, 103917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasco, M.; Villegas, L.; Yucra, S.; Rubio, J.; Gonzales, G.F. Dose-response effect of red maca (Lepidium meyenii) on benign prostatic hyperplasia induced by testosterone enanthate. Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-j.; Zhao, Q.-s.; Liu, Y.-l.; Gong, P.-f.; Cao, L.-l.; Wang, X.-d.; Zhao, B. Macamides present in the commercial maca (Lepidium meyenii) products and the macamide biosynthesis affected by postharvest conditions. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 3112–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabasz, D.; Szczeblewski, P.; Laskowski, T.; Płaziński, W.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Szwajgier, D.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Meissner, H.O. The distribution of glucosinolates in different phenotypes of Lepidium peruvianum and their role as acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors—in silico and in vitro studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, Z.; Men, L.; Li, J.; Gong, X. Deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasound-assisted strategy for simultaneous extraction of five macamides from Lepidium meyenii Walp and in vitro bioactivities. Foods 2023, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Tuli, H.S.; Mittal, S.; Shandilya, J.K.; Tiwari, A.; Sandhu, S.S. Isothiocyanates: A class of bioactive metabolites with chemopreventive potential. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 4005–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza, E.; Hadzich, A.; Kofer, W.; Mithofer, A.; Cosio, E.G. Bioactive maca (Lepidium meyenii) alkamides are a result of traditional Andean postharvest drying practices. Phytochemistry 2015, 116, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.V.; Fonseca Santana, L.; Diogenes, A.d.S.V.; Costa, S.L.; Zambotti-Villelae, L.; Colepicolo, P.; Ferraz, C.G.; Ribeiro, P.R. Combination of a multiplatform metabolite profiling approach and chemometrics as a powerful strategy to identify bioactive metabolites in Lepidium meyenii (Peruvian maca). Food Chem. 2021, 364, 130453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Bao, X.; Wang, Y.; Rasheed, M.; Guo, B. Authentication of the geographical origin of Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) at different regional scales using the stable isotope ratio and mineral elemental fingerprints. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 126058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.Z.; Li, W.Y. Characteristic fingerprinting based on macamides for discrimination of maca (Lepidium meyenii) by LC/MS/MS and multivariate statistical analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4475–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Yu, L.X.; Qu, H. Batch-to-batch quality consistency evaluation of botanical drug products using multivariate statistical analysis of the chromatographic fingerprint. AAPS PharmSciTech 2013, 14, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebiai, A.; Hemmami, H.; Zeghoud, S.; Ben Seghir, B.; Kouadri, I.; Eddine, L.S.; Elboughdiri, N.; Ghareba, S.; Ghernaout, D.; Abbas, N. Current application of chemometrics analysis in authentication of natural products: A review. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2022, 25, 945–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmaier, M.P.; Bernart, M.W.; Brinckmann, J.A. Advanced methodologies for the quality control of herbal supplements and regulatory considerations. Phytochem. Anal. 2025, 36, 2417–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, H.O.; Xu, L.; Wan, W.; Yi, F. Glucosinolates profiles in Maca phenotypes cultivated in Peru and China (Lepidium peruvianum syn. L. meyenii). Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 31, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dording, C.M.; Fisher, L.; Papakostas, G.; Farabaugh, A.; Sonawalla, S.; Fava, M.; Mischoulon, D. A double-blind, randomized, pilot dose-finding study of maca root (L. meyenii) for the management of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2008, 14, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okulicz, M.; Hertig, I.; Szkudelski, T. Differentiated effects of allyl isothiocyanate in diabetic rats: From toxic to beneficial action. Toxins 2022, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Wei, J.; Chen, R. Evaluation of the biological activity of glucosinolates and their enzymolysis products obtained from Lepidium meyenii Walp. (Maca). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Cao, N.; Wang, C. A review on β-carboline alkaloids and their distribution in foodstuffs: A class of potential functional components or not? Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Jahangeer, M.; Bouyahya, A.; El Omari, N.; Ghchime, R.; Balahbib, A.; Aboulaghras, S.; Mahmood, Z.; Akram, M.; Ali Shah, S.M.; et al. Heavy metal contamination of natural foods is a serious health issue: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilissao, L.E.B.; Rodrigues, C.F.; Porto, D.; Brabo, G.R.; Tassinari da Silva, A.; Puntel, R.L.; Paim, C.S.; Denardin, C.C.; Avila, D.S. Reprotoxicity induced by acute exposure to aqueous tuber extract of Peruvian Maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, H.O.; Kedzia, B.; Mrozikiewicz, P.M.; Mscisz, A. Short and long-term physiological responses of male and female rats to two dietary levels of pre-gelatinized maca (Lepidium peruvianum Chacon). Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006, 2, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Arimborgo, C.; Yupanqui, I.; Montero, E.; Alarcón-Yaquetto, D.E.; Zevallos-Concha, A.; Caballero, L.; Gasco, M.; Zhao, J.; Khan, I.A.; Gonzales, G.F. Acceptability, safety, and efficacy of oral administration of extracts of black or red maca (Lepidium meyenii) in adult human subjects: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta Ojeda, A.; Rodriguez Rojas, J.; Cancino-Lopez, J.; Barahona-Fuentes, G.; Pavez, L.; Yeomans-Cabrera, M.M.; Jorquera-Aguilera, C. Effects of maca (Lepidium meyenii Walp.) on physical performance in animals and humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2024, 17, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Lee, H.C.; Lin, Y.L.; Lin, Y.T.; Tsai, C.F.; Cheng, H.F. Identification of a new sildenafil analogue adulterant, desethylcarbodenafil, in a herbal supplement. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2016, 33, 1637–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaukuu, J.-L.Z.; Adams, Z.S.; Donkor-Boateng, N.A.; Mensah, E.T.; Bimpong, D.; Amponsah, L.A. Non-invasive prediction of maca powder adulteration using a pocket-sized spectrophotometer and machine learning techniques. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, I.; Gafner, S.; Techen, N.; Murch, S.J.; Khan, I.A. DNA barcoding for the identification of botanicals in herbal medicine and dietary supplements: Strengths and limitations. Planta Med. 2016, 82, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibitz Eisath, N.; Sturm, S.; Stuppner, H. Supercritical fluid chromatography in natural product analysis - An update. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study No. | Method Validation | Sensitivity a | Selectivity b | Throughput c | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-A | no | n. d. d | moderate | low | [26] |

| I-B | no | n. d. d | moderate-high | low | |

| II | partially | moderate-low | moderate | low | [27] |

| III | yes | moderate | moderate | moderate | [19] |

| IV | no | n. d. d | moderate | low | [58] |

| V | no | n. d. d | moderate | low | [13] |

| VI | yes | moderate-low | moderate | moderate | [56] |

| VII | yes | high-moderate | moderate-high | high | [54] |

| VIII | no | n. d. d | high | low | [59] |

| IX | yes | high | moderate | low | [23] |

| X | yes | low | low | n. a. e | [57] |

| XI | partially | high | moderate | low | [55] |

| XII | yes | low | moderate | moderate | [32] |

| XIII-A | yes | high | moderate | high | [30] |

| XIII-B | yes | moderate | high | moderate | |

| XIV | yes | high-moderate | high | high | [29] |

| XV | partially | n. d. d | high | low | [60] |

| XVI | yes | moderate | moderate | moderate | [61] |

| XVII | yes | high | high | high | [3] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wasilewicz, A.; Grienke, U. Maca (Lepidium meyenii) as a Functional Food and Dietary Supplement: A Review on Analytical Studies. Foods 2026, 15, 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020306

Wasilewicz A, Grienke U. Maca (Lepidium meyenii) as a Functional Food and Dietary Supplement: A Review on Analytical Studies. Foods. 2026; 15(2):306. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020306

Chicago/Turabian StyleWasilewicz, Andreas, and Ulrike Grienke. 2026. "Maca (Lepidium meyenii) as a Functional Food and Dietary Supplement: A Review on Analytical Studies" Foods 15, no. 2: 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020306

APA StyleWasilewicz, A., & Grienke, U. (2026). Maca (Lepidium meyenii) as a Functional Food and Dietary Supplement: A Review on Analytical Studies. Foods, 15(2), 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020306