Fabrication and Characterization of Pickering High Internal Phase Emulsions (P-HIPEs) Stabilized by a Complex of Soy Protein Isolate and a Newly Extracted Coix Polysaccharide

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Preparation of CP

2.3. Molecular Weight Analysis of CP

2.4. Monosaccharide Composition Analysis of CP

2.5. FT-IR Analysis of CP

2.6. Preparation and Characterization of SPI/CP Complex

2.7. Preparation of P-HIPEs

2.8. Optimization of SPI/CP Concentrations and pH in P-HIPEs

2.9. Characterization of P-HIPEs

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

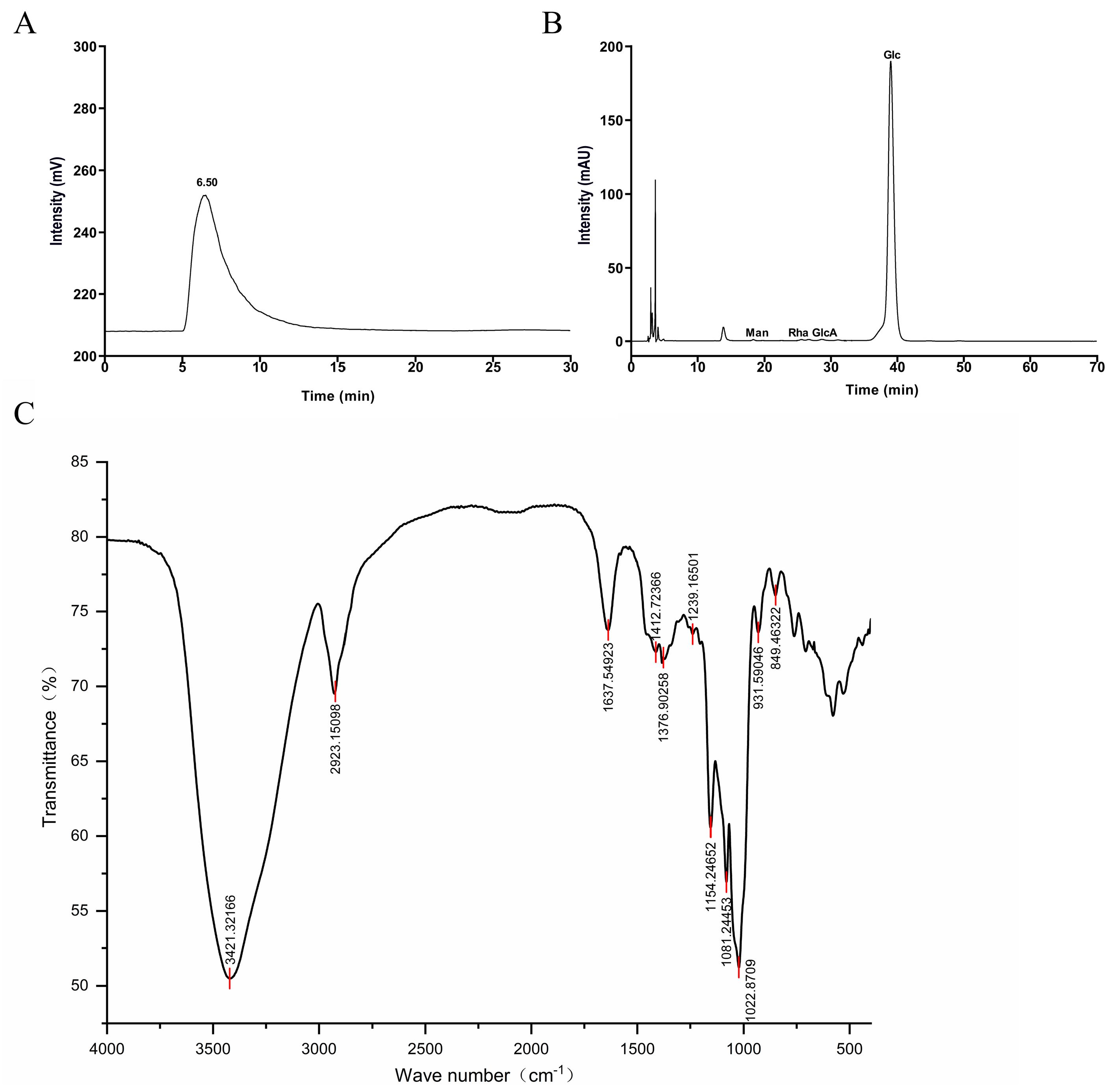

3.1. Molecular Weight and Monosaccharide Composition Analysis of CP

3.2. FT-IR Spectrometric Analysis of CP

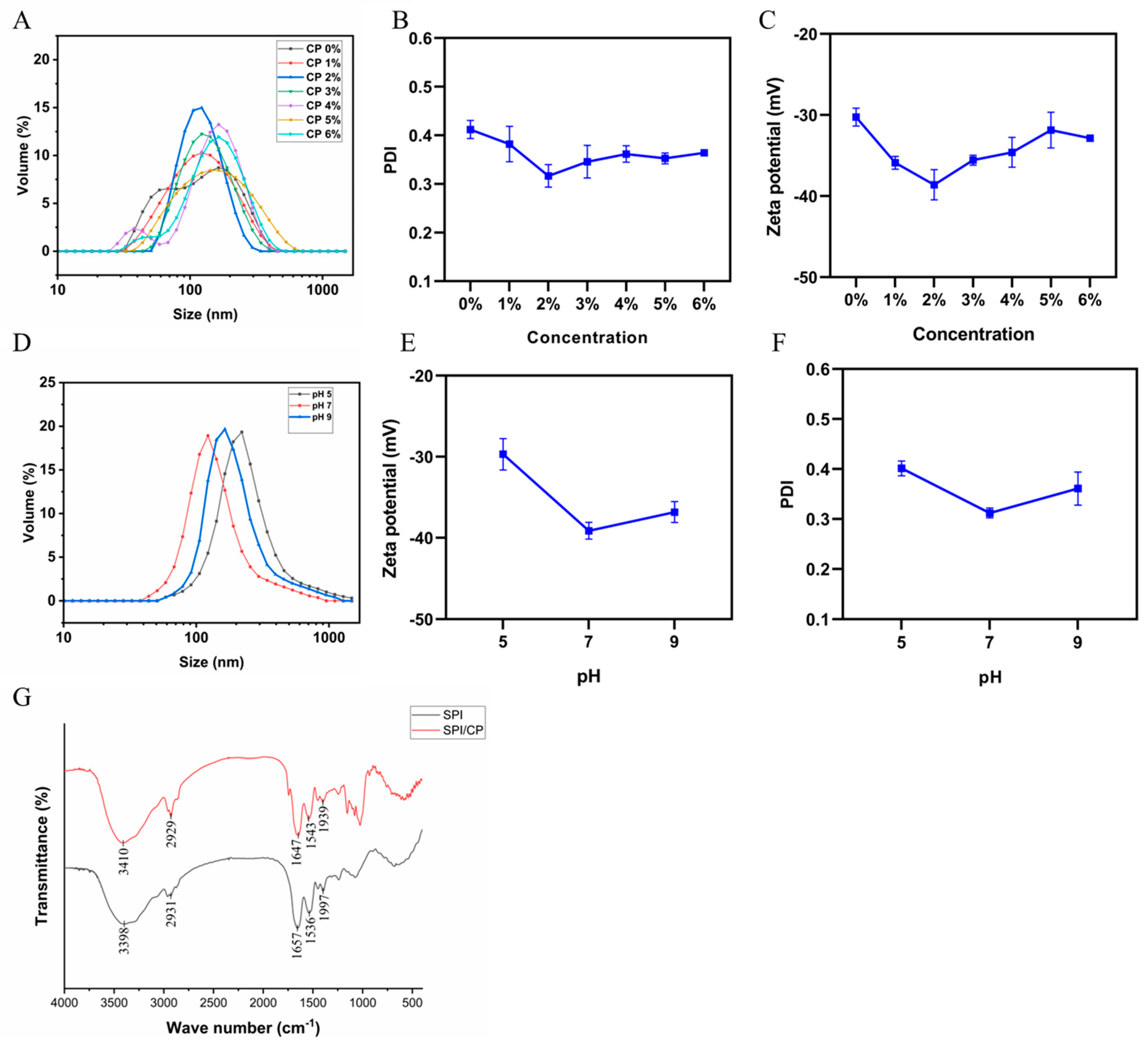

3.3. Characteristics of SPI/CP Complex

3.4. Characteristics of SPI/CP P-HIPEs

3.4.1. Visual Appearance and Creaming Index

3.4.2. Particle Size and Zeta Potential

3.4.3. Microstructure

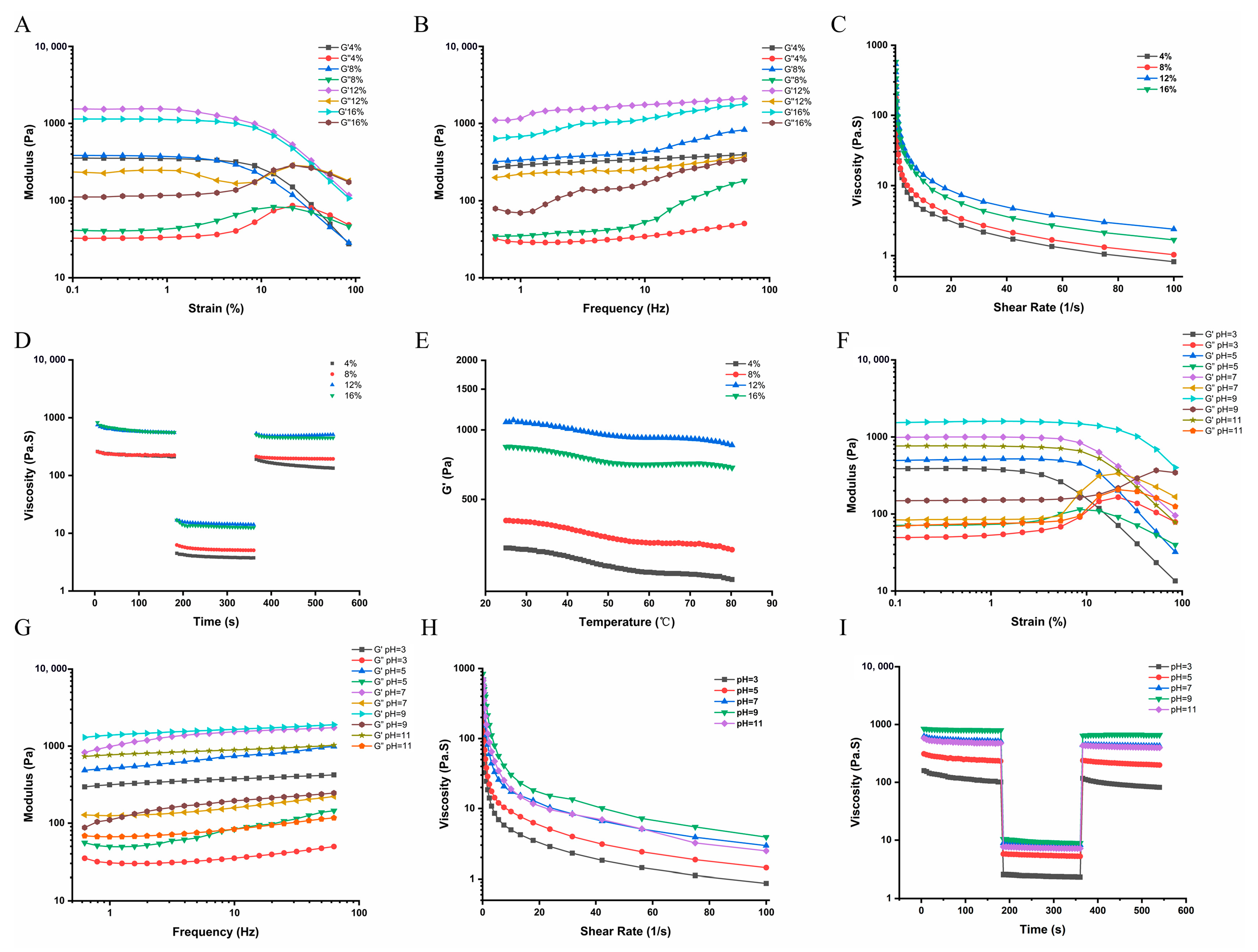

3.4.4. Rheological Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Zhao, J.; Yang, J.; Xie, Y. Improvement strategies for the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble flavonoids: An overview. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 570, 118642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassani, L.; Gomez-Zavaglia, A. Pickering emulsions in food and nutraceutical technology: From delivering hydrophobic compounds to cutting-edge food applications. Explor. Foods Foodomics 2024, 2, 408–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Chen, W.; Marchioni, E. Protein-Based High Internal Phase Pickering Emulsions: A Review of Their Fabrication, Composition and Future Perspectives in the Food Industry. Foods 2023, 12, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Fan, L.; Li, J.; Zhong, S. Pickering emulsions stabilized by biopolymer-based nanoparticles or hybrid particles for the development of food packaging films: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 146, 109185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Yang, S.; Cheng, L.; Liao, P.; Dai, S.; Tong, X.; Tian, T.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L. Emulsifying properties and oil–water interface properties of succinylated soy protein isolate: Affected by conformational flexibility of the interfacial protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Feng, X.; Kong, Q.; Ren, X. Efficient binding paradigm of protein and polysaccharide: Preparation of isolated soy protein-chitosan quaternary ammonium salt complex system and exploration of its emulsification potential. Food Chem. 2023, 407, 135111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, T.; Wu, G. Characteristic of the interaction mechanism between soy protein isolate and functional polysaccharide with different charge characteristics and exploration of the foaming properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 150, 109615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wen, A.; Qin, L.; Zhu, Y. Effect of Coix Seed Extracts on Growth and Metabolism of Limosilactobacillus reuteri. Foods 2022, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Liu, C.-S.; Hu, Y.-N.; Luo, Z.-Y.; Chen, F.-L.; Yuan, L.-X.; Tan, X.-M. Coix seed polysaccharides alleviate type 2 diabetes mellitus via gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids activation of IGF1/PI3K/AKT signaling. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Xu, D. Isolation and identification of anti-inflammatory and analgesic polysaccharides from Coix seed (Coix lacryma-jobi L.var. Ma-yuen (Roman.) Stapf). Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 38, 2165–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Xu, F.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Mo, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from coix seeds: Optimization, purification, and in vitro digestibility. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Wu, C.; Fan, G.; Kou, X.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Dou, J.; Zhou, Y. Rheological properties, gel properties and 3D printing performance of soy protein isolate gel inks added with different types of apricot polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Song, H.; Liu, H. Metal cation-induced conformational changes of soybean protein isolate/soybean soluble polysaccharide and their effects on high-internal-phase emulsion properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 3341–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejaszek, I.; Surówka, K. Protein-polysaccharide complexes from soy protein and carrageenan obtained by electrosynthesis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 368, 124188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyaya, M.; Bolzinger, M.-A.; Chevalier, Y.; Bordes, C. Rheological properties and stability of Pickering emulsions stabilized with differently charged particles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 687, 133514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, C.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Luo, D.; Shah, B.R. Stability, microstructural and rheological properties of Pickering emulsion stabilized by xanthan gum/lysozyme nanoparticles coupled with xanthan gum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.S. Phenol-Sulfuric Acid Method for Total Carbohydrates. In Food Analysis Laboratory Manual; Nielsen, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Xiong, L.; Shen, X. Extraction optimization, purification, characterization, and hypolipidemic activities of polysaccharide from pumpkin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 141907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirgarian, B.; Farmani, J.; Farahmandfar, R.; Milani, J.M.; Van Bockstaele, F. Ultra-stable high internal phase emulsions stabilized by protein-anionic polysaccharide Maillard conjugates. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, D.; Tan, M. Pickering emulsions stabilized by Chlorella pyrenoidosa protein–chitosan complex for lutein encapsulation. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 2807–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, L.-M. Chemical structural and chain conformational characterization of some bioactive polysaccharides isolated from natural sources. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 76, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, Z. Structural characteristics of polysaccharide from Zingiber striolatum and its effects on gut microbiota composition in obese mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Linhardt, R.J. Structural and immunological studies on the polysaccharide from spores of a medicinal entomogenous fungus Paecilomyces cicadae. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjati, M.; Noshad, M.; Sorourian, R.; Askari, H.; Feghhi, S. Effect of gamma irradiation on structure, physicochemical and functional properties of bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia) seeds polysaccharides. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2023, 202, 110569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, Z.; Hao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, G.; Guo, X. Structural characterization of a new high molecular weight polysaccharide from jujube fruit. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1012348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Hua, D.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, C. Characterization of a new heteropolysaccharide from green guava and its application as an α-glucosidase inhibitor for the treatment of type II diabetes. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3997–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Zhu, P.; Ma, S.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y. Purification, characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from stem lettuce. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 188, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Huang, R.; Wen, P.; Song, Y.; He, B.; Tan, J.; Hao, H.; Wang, H. Structural characterization and immunological activity of pectin polysaccharide from kiwano (Cucumis metuliferus) peels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yin, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W. A glucomannogalactan from Pleurotus geesteranus: Structural characterization, chain conformation and immunological effect. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 287, 119346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.; Ma, W.; Kuang, J.; Huang, J.; Xiong, Y.L. Textural properties, microstructure and digestibility of mungbean starch–flaxseed protein composite gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 126, 107482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.-M.; Yi, Y.; Wang, H.-X.; Huang, F. Investigation of the Maillard Reaction between Polysaccharides and Proteins from Longan Pulp and the Improvement in Activities. Molecules 2017, 22, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, M.; Tian, Y.; Lou, F.; Liu, J.; Jiang, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z. Conformational changes induced by nanocellulose with different morphologies and aspect ratios enhance the solubility of acidic soy protein isolate at pH=4.0. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 168, 111542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.Y.; Zhong, S.L.; He, S.H.; Gao, Y.; Cui, X.J. Constructing of pH and reduction dual-responsive folic acid-modified hyaluronic acid-based microcapsules for dual-targeted drug delivery via sonochemical method. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 44, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, S.; Li, B.; Li, Y. Complex of raw chitin nanofibers and zein colloid particles as stabilizer for producing stable pickering emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 97, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, X.-W.; Guo, J.; Yin, S.-W.; Yang, X.-Q. Wheat gluten based percolating emulsion gels as simple strategy for structuring liquid oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 61, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Liu, C.; Shi, J.; Ni, F.; Qi, J.; Shen, Q.; Huang, M.; Ren, G.; Tian, S.; Lin, Q.; et al. Fabrication and characterization of oil-in-water pickering emulsions stabilized by ZEIN-HTCC nanoparticles as a composite layer. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Cao, Y.; Song, H. Fabrication and Characterization of Pickering High Internal Phase Emulsions (P-HIPEs) Stabilized by a Complex of Soy Protein Isolate and a Newly Extracted Coix Polysaccharide. Foods 2026, 15, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010079

Li H, Cao Y, Song H. Fabrication and Characterization of Pickering High Internal Phase Emulsions (P-HIPEs) Stabilized by a Complex of Soy Protein Isolate and a Newly Extracted Coix Polysaccharide. Foods. 2026; 15(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010079

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hong, Yubo Cao, and Haizhao Song. 2026. "Fabrication and Characterization of Pickering High Internal Phase Emulsions (P-HIPEs) Stabilized by a Complex of Soy Protein Isolate and a Newly Extracted Coix Polysaccharide" Foods 15, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010079

APA StyleLi, H., Cao, Y., & Song, H. (2026). Fabrication and Characterization of Pickering High Internal Phase Emulsions (P-HIPEs) Stabilized by a Complex of Soy Protein Isolate and a Newly Extracted Coix Polysaccharide. Foods, 15(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010079