Analysis of Elemental Concentrations and Risk Assessment of Prepared Livestock and Poultry Meat Dishes Sold in Zhejiang Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instruments and Reagents

2.2. Sample Pretreatment

2.3. ICP-MS Parameters

2.4. Quality Control

2.5. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

2.6. Risk Assessment Methods

2.7. Health Risk Assessment of Hazardous Elements

- (1)

- Non-carcinogenic risk assessment

- (2)

- Carcinogenic risk assessment

2.8. Data Processing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Linear Range and LOD

3.2. Accuracy and Precision

3.3. Multi-Element Concentrations in Prepared Livestock and Poultry Meat Products

3.4. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

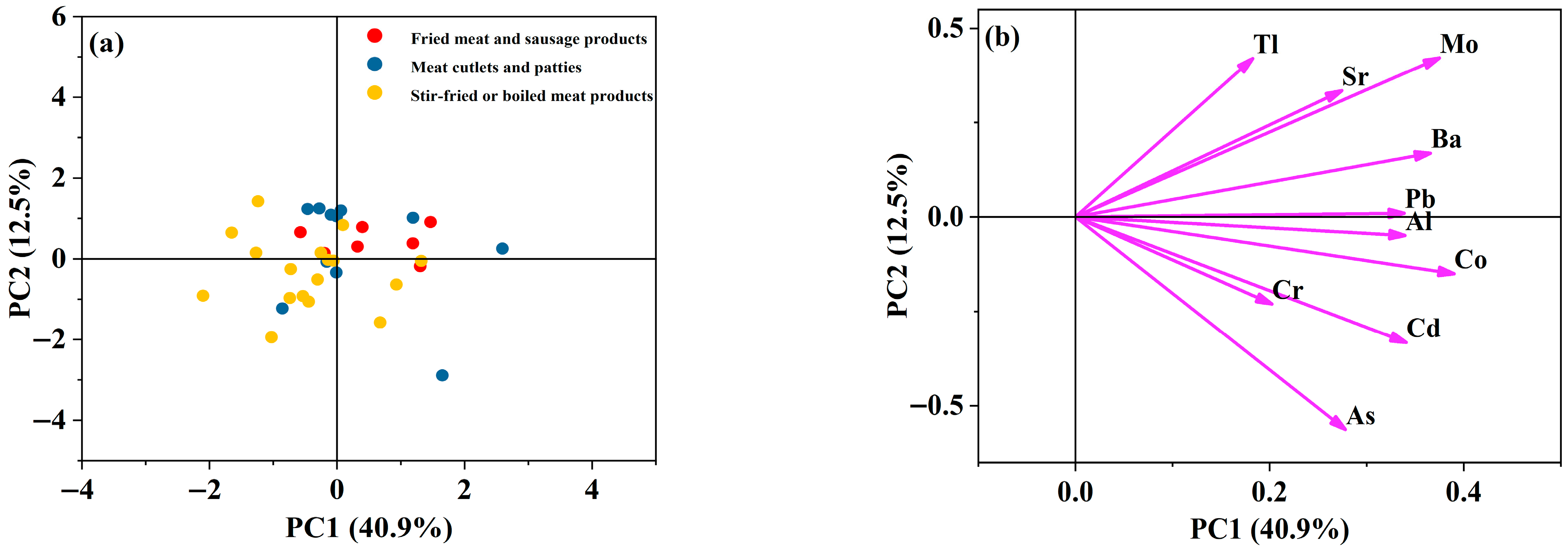

3.4.1. PCA of Contamination Patterns

3.4.2. HCA of Clustering Patterns

3.5. Assessment of Hazardous Element Contamination

3.6. Dietary Exposure Risk Assessment of Hazardous Elements

3.6.1. Non-Carcinogenic Risk Assessment

3.6.2. Carcinogenic Risk Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- People’s Daily Online Research Institute. Pre-Made Dishes Industry Development Report. 2023. Available online: http://yjy.people.com.cn/n1/2023/0710/c440911-40031856.html (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- IiMedia Research. White Paper on the Development of China’s Prefabricated Vegetable Industry in 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/92015.html (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- State Administration for Market Regulation. Notice on Strengthening Food Safety Supervision of Prepared Dishes to Promote High-Quality Development of the Industry. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202403/content_6940808.htm (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- U.S. FDA. Control of Listeria Monocytogenes in Ready-to-Eat Foods: Guidance for Industry Draft Guidance; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017.

- UKHSA. Guidelines for Assessing the Microbiological Safety of Ready-to-Eat Foods Placed on the Market; UK Health Security Agency: London, UK, 2024.

- Wu, R.-T.; Cai, Y.-F.; Chen, Y.-X.; Yang, Y.-W.; Xing, S.-C.; Liao, X.-D. Occurrence of Microplastic in Livestock and Poultry Manure in South China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 277, 116790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fx361 Industry Research Center. Development Status and Market Structure of China’s Prepared Food (Prefabricated Dishes) Industry in 2022. 2024. Available online: https://m.fx361.com/news/2024/0101/25858483.html (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Human. 2024. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/ (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y. Human Health Risk Assessment of Cadmium via Dietary Intake by Children in Jiangsu Province, China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2017, 39, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfferth, A.L.; Limmer, M.A.; Runkle, B.R.K.; Chaney, R.L. Mitigating Toxic Metal Exposure Through Leafy Greens: A Comprehensive Review Contrasting Cadmium and Lead in Spinach. Geohealth 2024, 8, e2024GH001081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.I.; Alam, M.R. Health Effects of Heavy Metals in Meat and Poultry Consumption in Noakhali, Bangladesh. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 12, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hassanin, A.S.; Samak, M.R.; Abdel-Rahman, G.N.; Abu-Sree, Y.H.; Saleh, E.M. Risk Assessment of Human Exposure to Lead and Cadmium in Maize Grains Cultivated in Soils Irrigated Either with Low-Quality Water or Freshwater. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahir, A.; Ge, Z.; Khan, I.A. Public Health Risks Associated with Food Process Contaminants—A Review. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, G.K.; Panjagari, N.R. Review on Metal Packaging: Materials, Forms, Food Applications, Safety and Recyclability. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2377–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-T.; Linh, T.T.T.; Vo, T.-K.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Van, T.-K. Analytical Techniques for Determination of Heavy Metal Migration from Different Types of Locally Made Plastic Food Packaging Materials Using ICP-MS. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 4030–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaly, H.F.; Sharkawy, A.A. Health Risk Assessment of Metals in Chicken Meat and Liver in Egypt. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrauch, K.; Duverna, R.; Sisco, P.N.; Domesle, A.; Bilanovic, I. A Survey of the Levels of Selected Metals in U.S. Meat, Poultry, and Siluriformes Fish Samples Taken at Slaughter and Retail, 2017–2022. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.268-2025; Determination of Multi-Elements in Foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2025.

- Bernardin, M.; Bessueille-Barbier, F.; Le Masle, A.; Lienemann, C.-P.; Heinisch, S. Suitable Interface for Coupling Liquid Chromatography to Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry for the Analysis of Organic Matrices. 1 Theoretical and Experimental Considerations on Solute Dispersion. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1565, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S.; Levstek, L.; Žigon, D.; Ščančar, J.; Milačič, R. Speciation and Bio-Imaging of Chromium in Taraxacum Officinale Using HPLC Post-Column ID-ICP-MS, High Resolution MS and Laser Ablation ICP-MS Techniques. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 863387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Second Workshop on Reliable Evaluation of Low-Level Contamination of Food; WHO: Rome, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, S.; Hamadi, K.; Zergui, A.; Djouad, M.E. Multi-Element Analysis of Food Dyes and Assessment of Consumer’s Health. Food Addit. Contam. Part B Surveill. 2024, 17, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 2762-2022; National Food Safety Standard-Maximum Levels of Contaminants in Foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2024; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2024/indexch.htm (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/AtoZ/?list_type=alpha (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China. Chinese Exposure Factors Handbook (Adults); China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Saleem, M.; Wang, Y.; Pierce, D.; Sens, D.A.; Somji, S.; Garrett, S.H. Concentration and Potential Non-Carcinogenic and Carcinogenic Health Risk Assessment of Metals in Locally Grown Vegetables. Foods 2025, 14, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Toxicological Review of Hexavalent Chromium (Cr(VI)) (Final Report); Integrated Risk Information System, EPA (ORD), U.S. EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/ChemicalLanding/%26substance_nmbr%3D144 (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Toxicological Review of Inorganic Arsenic (Final Report); Integrated Risk Information System, EPA (ORD), U.S. EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/ChemicalLanding/%26substance_nmbr%3D278 (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Evaluate the Evidence to Examine Cancer Effects. In-Depth Toxicological Analysis, Public Health Assessment Guidance Manual; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, ATSDR: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pha-guidance/conducting_scientific_evaluations/indepth_toxicological_analysis/EvaluateEvidenceCancerEffects.html (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA). Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants: Ninety-First Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; WHO Technical Report Series No. 1023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Millour, S.; Noël, L.; Chekri, R.; Vastel, C.; Kadar, A.; Sirot, V.; Leblanc, J.-C.; Guérin, T. Strontium, Silver, Tin, Iron, Tellurium, Gallium, Germanium, Barium and Vanadium Levels in Foodstuffs from the Second French Total Diet Study. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2012, 25, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.J.; Ashmore, E. Risk Assessment of Antimony, Barium, Beryllium, Boron, Bromine, Lithium, Nickel, Strontium, Thallium and Uranium Concentrations in the New Zealand Diet. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredi, A.; Varrà, M.O.; Zanardi, E.; Vitellino, M.; Peloso, M.; Lorusso, P.; Ghidini, S.; Bonerba, E.; Accurso, D. Dietary Exposure Assessment to Nickel through the Consumption of Poultry, Beef, and Pork Meat for Different Age Groups in the Italian Population. Ital. J. Food Safety 2025, 14, 13840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhanardakani, S.; Tayebi, L.; Hosseini, S.V. Health Risk Assessment of Arsenic and Heavy Metals (Cd, Cu, Co, Pb, and Sn) through Consumption of Caviar of Acipenser Persicus from Southern Caspian Sea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 2664–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwegbue, C.M.A. Metal Concentrations in Selected Brands of Canned Fish in Nigeria: Estimation of Dietary Intakes and Target Hazard Quotients. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, M.S.; Rana, S.; Yamazaki, S.; Aono, T.; Yoshida, S. Health Risk Assessment for Carcinogenic and Non-Carcinogenic Heavy Metal Exposures from Vegetables and Fruits of Bangladesh. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2017, 3, 1291107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, C.; Yu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yao, W.; Guo, Y.; Qian, H. Chemical Food Contaminants during Food Processing: Sources and Control. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latunde-Dada, G.O.; Kajarabille, N.; Rose, S.; Arafsha, S.M.; Kose, T.; Aslam, M.F.; Hall, W.L.; Sharp, P.A. Content and Availability of Minerals in Plant-Based Burgers Compared with a Meat Burger. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.L. Toxic Trace Elements in Meat and Meat Products Across Asia: A Comprehensive Literature Review and Implications for Human Health. Foods 2024, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.I.; Shill, L.C.; Raihan, M.M.; Rashid, R.; Bhuiyan, M.N.H.; Reza, S.; Alam, M.R. Human Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Vegetables of Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakody, J.A.K.S.; Edirisinghe, E.M.R.K.B.; Senevirathne, S.A.; Senarathna, L. Total Arsenic and Arsenic Species in Selected Seafoods: Analysis Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography—Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry and Health Risk Assessment. J. Chromatogr. Open 2024, 6, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Tan, H.; Cheng, C.; Li, P.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, Y. Development of a Fast Method Using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry Coupled with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Exploration of the Reduction Mechanism of Cr(VI) in Foods. Toxics 2024, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ICP-MS Parameters | |

|---|---|

| RF power | 1300 W |

| Nebulier flow rate | 1.05 L min−1 |

| Plasma gas flow rate | 18.0 L min−1 |

| Auxiliary gas flow rate | 1.2 L min−1 |

| Cell gas B flow rate | 1.4 mL min−1 5% H2 in He |

| RPQ | 0.45 |

| Sampling cone/ Skimmer cone | 1.0/0.4 (Pt) |

| Isotopes monitored | 27Al, 52Cr, 59Co, 60Ni, 75As, 88Sr, 95Mo, 111Cd, 137Ba, 205Tl, 208Pb, 45Sc, 73Ge, 89Y, 115In, 209Bi |

| Dwell time | 50 ms |

| Sweeps | 40 |

| Data acquisition mode | Time resolved analysis |

| Elements | Food Category | ML (mg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Pb | Meat products (excluding livestock and poultry offal products) | 0.3 |

| Livestock and poultry offal products | 0.5 | |

| Cd | Meat and meat products (excluding livestock and poultry offal and their products) | 0.1 |

| Livestock and poultry liver and liver products | 0.5 | |

| Livestock and poultry kidney and kidney products | 1.0 | |

| Cr | Meat and meat products | 1.0 |

| As | Meat and meat products | 0.5 |

| Elements | Linear Equation | Linear Range (μg L−1) | Correlation Coefficient (r) | LOD (mg kg−1) | LOQ (mg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | y = 301.97x + 736.63 | 10.0–500.0 | 0.9999 | 0.50 | 1.67 |

| Cr | y = 11,777.62x + 604.81 | 1.0–50.0 | 1.0000 | 0.051 | 0.17 |

| Co | y = 32,024.79x + 38.37 | 1.0–50.0 | 0.9999 | 0.0010 | 0.0033 |

| Ni | y = 8008.09x + 358.12 | 1.0–50.0 | 0.9999 | 0.20 | 0.67 |

| As | y = 1612.19x + 37.08 | 1.0–50.0 | 1.0000 | 0.0021 | 0.0070 |

| Sr | y = 9050.98x + 111.65 | 1.0–50.0 | 1.0000 | 0.20 | 0.67 |

| Mo | y = 10,306.13x + 10.01 | 1.0–50.0 | 0.9998 | 0.010 | 0.033 |

| Cd | y = 5565.07x + 4.98 | 1.0–50.0 | 0.9999 | 0.0021 | 0.0071 |

| Ba | y = 4418.21x + 148.00 | 1.0–50.0 | 0.9999 | 0.020 | 0.067 |

| Tl | y = 173,927.43x + 141.66 | 1.0–50.0 | 0.9998 | 0.00018 | 0.00060 |

| Pb | y = 1,034,842.83x + 3458.30 | 1.0–50.0 | 0.9999 | 0.020 | 0.067 |

| Elements | SRM1577c | GBW10018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certified Values | Measured Average Values | RSD (%) | Certified Values | Measured Average Values | RSD (%) | |

| Al | 160 ± 30 | 152 | 4.50 | |||

| Cr | 0.053 ± 0.014 | 0.049 | 15.1 | 0.59 ± 0.11 | 0.56 | 3.23 |

| Co | 0.300 ± 0.018 | 0.303 | 3.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.57 |

| Ni | 0.044 ± 0.009 | 0.048 | 6.63 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.14 | 4.90 |

| As | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 0.020 | 9.20 | 0.109 ± 0.013 | 0.107 | 4.02 |

| Sr | 0.095 ± 0.004 | 0.097 | 4.29 | 0.64 ± 0.08 | 0.69 | 5.91 |

| Mo | 3.3 ± 0.13 | 3.27 | 1.77 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.12 | 3.65 |

| Cd | 0.097 ± 0.001 | 0.096 | 2.12 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 2.32 |

| Ba | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.7 | 6.60 | |||

| Tl | 0.014 | 0.014 | 3.20 | |||

| Pb | 0.063 ± 0.001 | 0.064 | 5.85 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.12 | 6.77 |

| Elements | Detection Rate (%) | Median | Q1 | Q3 | IQR | Outliers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 100 | 3.88 | 2.92 | 6.77 | 3.85 | 22.4 |

| Cr | 48.6 | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.066 | 0.040 | 0.18; 0.29; 0.62 |

| Co | 94.3 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.021; 0.030 |

| Ni | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.00 | |

| As | 88.6 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.012; 0.47 |

| Sr | 97.1 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 1.27 | 0.76 | 2.49; 2.93 |

| Mo | 91.4 | 0.036 | 0.022 | 0.052 | 0.030 | 0.15; 0.15; 0.44 |

| Cd | 25.7 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.0013 | 0.0003 | 0.003; 0.005; 0.013; 0.020 |

| Ba | 100 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.26 | |

| Tl | 42.9 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.002; 0.003; 0.007 |

| Pb | 48.6 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.031 | 0.021 | 0.066; 0.072; 0.084; 0.167 |

| Dishes | Pi | Pollution Level | Pc | Safety Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cd | Cr | As | ||||

| Fried meat and sausage products | 0.033–0.11 | 0.011–0.026 | 0.026–0.11 | 0.002–0.014 | Unpolluted | 0.027–0.087 | Safe |

| Stir-fried or boiled meat products | 0.033–0.14 | 0.011–0.022 | 0.026–0.085 | 0.002–0.025 | Unpolluted | 0.027–0.10 | Safe |

| Meat cutlets and patties | 0.033–0.086 | 0.011–0.020 | 0.026–0.059 | 0.004–0.009 | Unpolluted | 0.027–0.065 | Safe |

| Black pepper chicken nuggets | 0.28 | 0.011 | 0.081 | 0.014 | Slight Pb pollution | 0.21 | Safe |

| Quinoa chicken steak | 0.24 | 0.018 | 0.059 | 0.010 | Slight Pb pollution | 0.18 | Safe |

| Vegetable chicken patty | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.011 | Slight Pb pollution | 0.19 | Safe |

| Sweet and sour pork | 0.56 | 0.016 | 0.085 | 0.013 | Slight Pb pollution | 0.41 | Safe |

| Braised meat paste | 0.033 | 0.052 | 0.29 | 0.012 | Slight Cr pollution | 0.22 | Safe |

| Pork-tripe chicken | 0.033 | 0.011 | 0.62 | 0.005 | Moderate Cr pollution | 0.46 | Safe |

| Codfish cake (containing pork loin) | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.026 | 0.94 | Moderate As pollution | 0.70 | Safe |

| Dishes | Population | THQ | TTHQ | Risk Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cd | Cr | As | ||||

| Fried meat and sausage products | Adults | 0.007–0.058 | 0.003–0.006 | 0.021–0.086 | 0.009–0.057 | 0.039–0.18 | Acceptable |

| Children | 0.014–0.12 | 0.006–0.012 | 0.043–0.18 | 0.018–0.12 | 0.080–0.37 | Acceptable | |

| Stir-fried or boiled meat products | Adults | 0.007–0.12 | 0.003–0.013 | 0.021–0.50 | 0.009–0.10 | 0.039–0.54 | Acceptable |

| Children | 0.014–0.25 | 0.006–0.027 | 0.043–1.03 | 0.018–0.21 | 0.080–1.11 | Potential Risk (Pork-tripe chicken) | |

| Meat cutlets and patties | Adults | 0.007–0.050 | 0.003–0.048 | 0.026–0.18 | 0.017–3.8 | 0.049–3.9 | Potential Risk (Codfish cake (containing pork loin)) |

| Children | 0.014–0.10 | 0.006–0.099 | 0.054–0.37 | 0.035–0.093 | 0.10–8.0 | Potential Risk (Codfish cake (containing pork loin)) | |

| Dishes | R | Risk Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr(VI) | iAs | Cr(VI) | iAs | |

| Fried meat and sausage products | 1.0 × 10−5–4.1 × 10−5 | 4.0 × 10−6–2.5 × 10−5 | Acceptable | Acceptable |

| Stir-fried or boiled meat products | 1.0 × 10−5–3.3 × 10−5 | 4.0 × 10−6–4.5 × 10−5 | Acceptable | Acceptable |

| Meat cutlets and patties | 1.0 × 10−5–7.1 × 10−5 | 8.0 × 10−6–2.0 × 10−5 | Acceptable | Acceptable |

| Braised meat paste | 1.0 × 10−4 | 2.2 × 10−5 | Risky | Acceptable |

| Pork-tripe chicken | 2.4 × 10−4 | 9.0 × 10−6 | Risky | Acceptable |

| Codfish cake (containing pork loin) | 1.0 × 10−5 | 1.7 × 10−3 | Acceptable | Risky |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, C.; Tan, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J. Analysis of Elemental Concentrations and Risk Assessment of Prepared Livestock and Poultry Meat Dishes Sold in Zhejiang Province. Foods 2026, 15, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010073

Zheng C, Tan Y, Hu Z, Zhang J, Tang J. Analysis of Elemental Concentrations and Risk Assessment of Prepared Livestock and Poultry Meat Dishes Sold in Zhejiang Province. Foods. 2026; 15(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Chenyang, Ying Tan, Zhengyan Hu, Jingshun Zhang, and Jun Tang. 2026. "Analysis of Elemental Concentrations and Risk Assessment of Prepared Livestock and Poultry Meat Dishes Sold in Zhejiang Province" Foods 15, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010073

APA StyleZheng, C., Tan, Y., Hu, Z., Zhang, J., & Tang, J. (2026). Analysis of Elemental Concentrations and Risk Assessment of Prepared Livestock and Poultry Meat Dishes Sold in Zhejiang Province. Foods, 15(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010073