The Impact of Sulfite Reduction Alternatives with Various Antioxidants on the Quality of Semi-Sweet Wines

Abstract

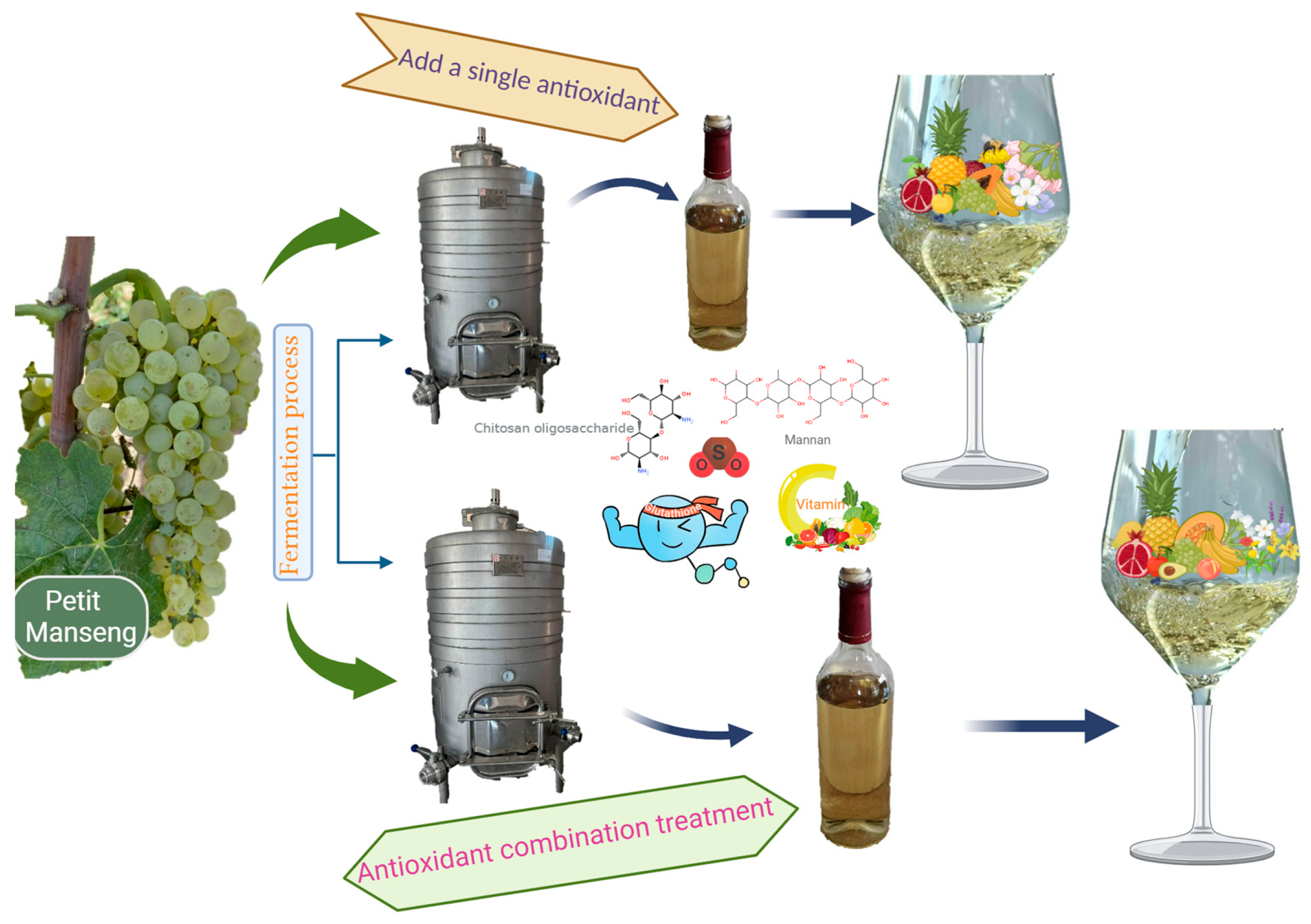

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Winemaking Materials and Conditions

2.2. Experimental Treatments

2.3. Analyses of Wines After the Addition of Antioxidants

2.3.1. Determination of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.3.2. Determination of Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity

2.3.3. Determination of Wine Color

2.3.4. Determination of Total Phenols and Total Flavonoids

2.3.5. Determination of Monomeric Phenols

2.3.6. Determination of Amino Acids

2.3.7. Determination of Volatile Compounds

2.4. Sensory Evaluation Method

| Birth Year | Number and Gender |

|---|---|

| born after 2000 | 1 male and 1 female |

| born between 1990 and 1999 | 2 males and 1 female |

| born between 1980 and 1989 | 1 male and 2 females |

| born between 1970 and 1979 | 1 female |

| born after 1969 | 1 male |

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Different Antioxidants on Semi-Sweet Wines

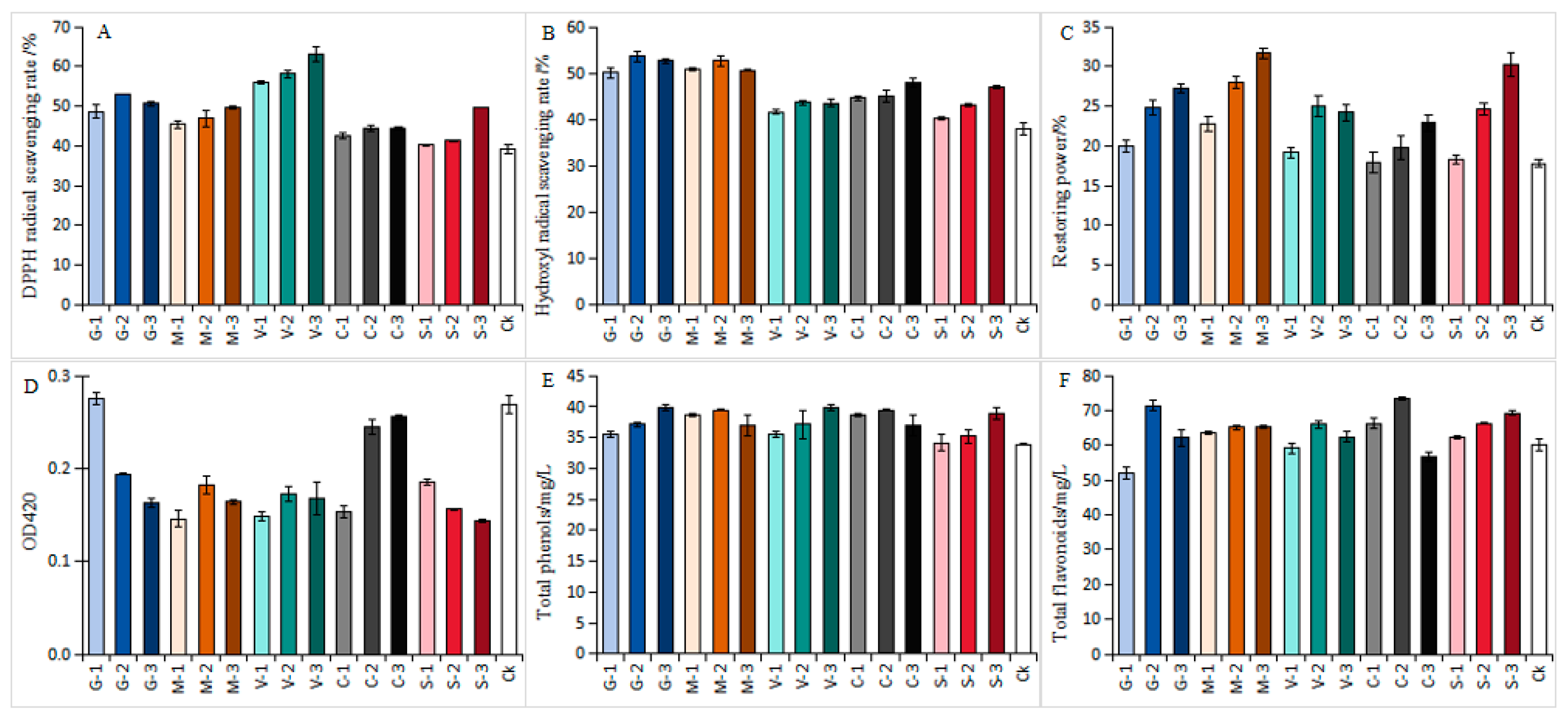

3.1.1. Effects of Different Antioxidants on the Antioxidant Capacity of White Wines

3.1.2. Sensory Evaluation of Semi-Sweet Wine Under Different Antioxidants

3.2. Treatment of Semi-Sweet White Wine with Combinations of Various Antioxidants

3.2.1. The Combined Effects of Various Antioxidants on the Polyphenol Content in Semi-Sweet Wine

3.2.2. The Combined Effects of Different Antioxidants on the Amino Acid Content in Semi-Sweet Wine

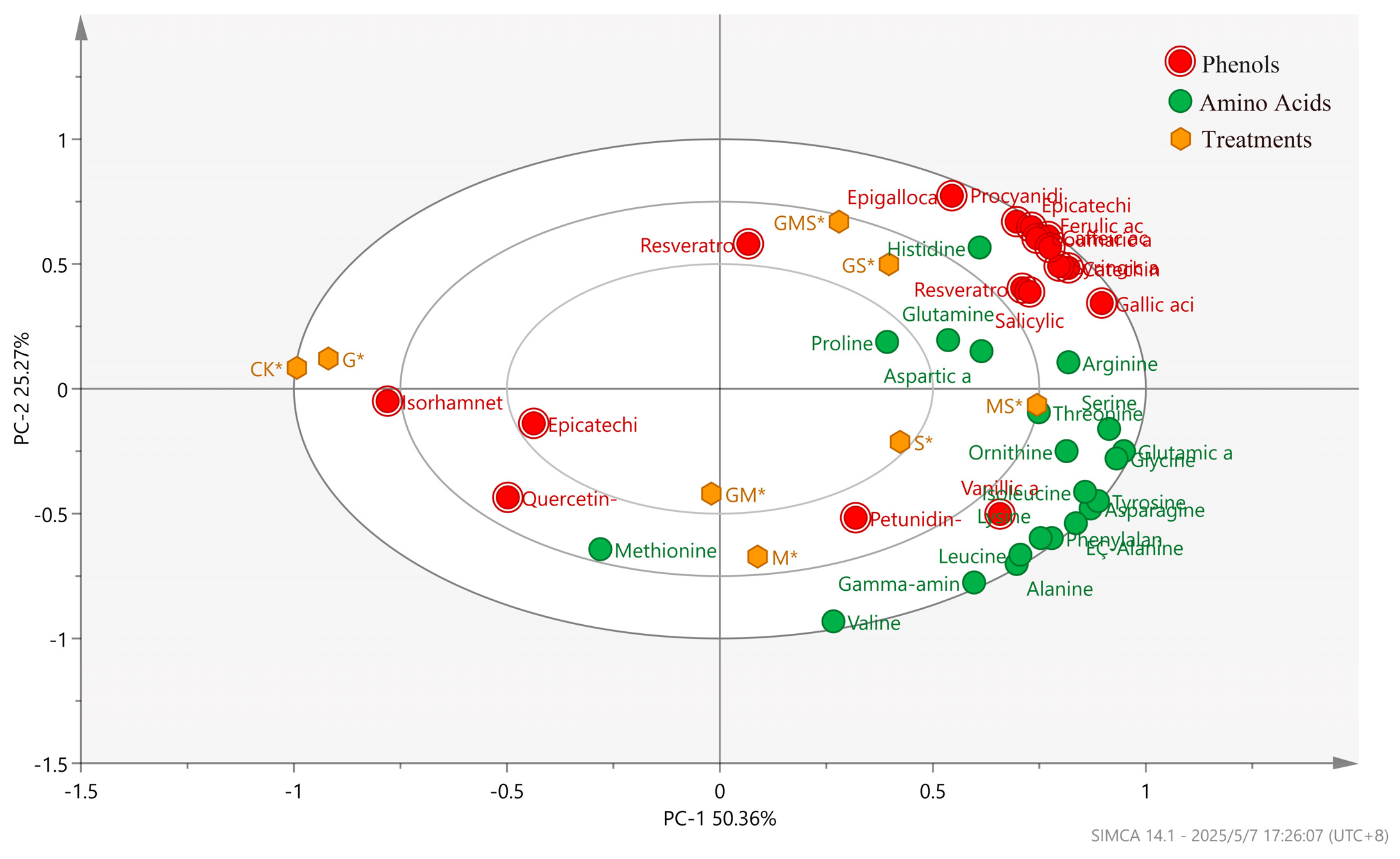

3.2.3. PCA of Monophenols and Amino Acids in Semi-Sweet Wine Under the Combined Effects of Different Antioxidants

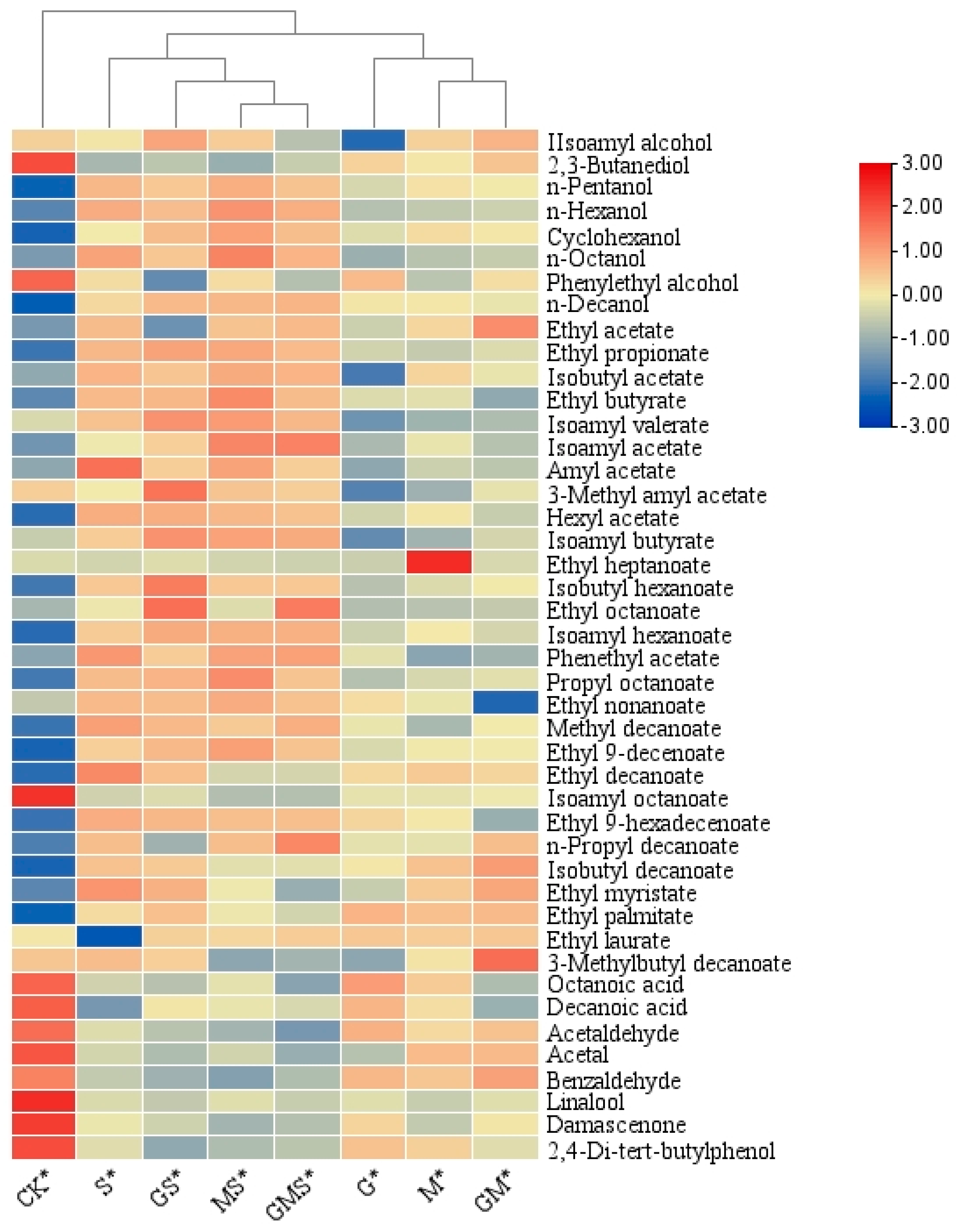

3.2.4. Analysis of the Differences in Aroma Compounds in Semi-Sweet Wine Treated with Various Antioxidants

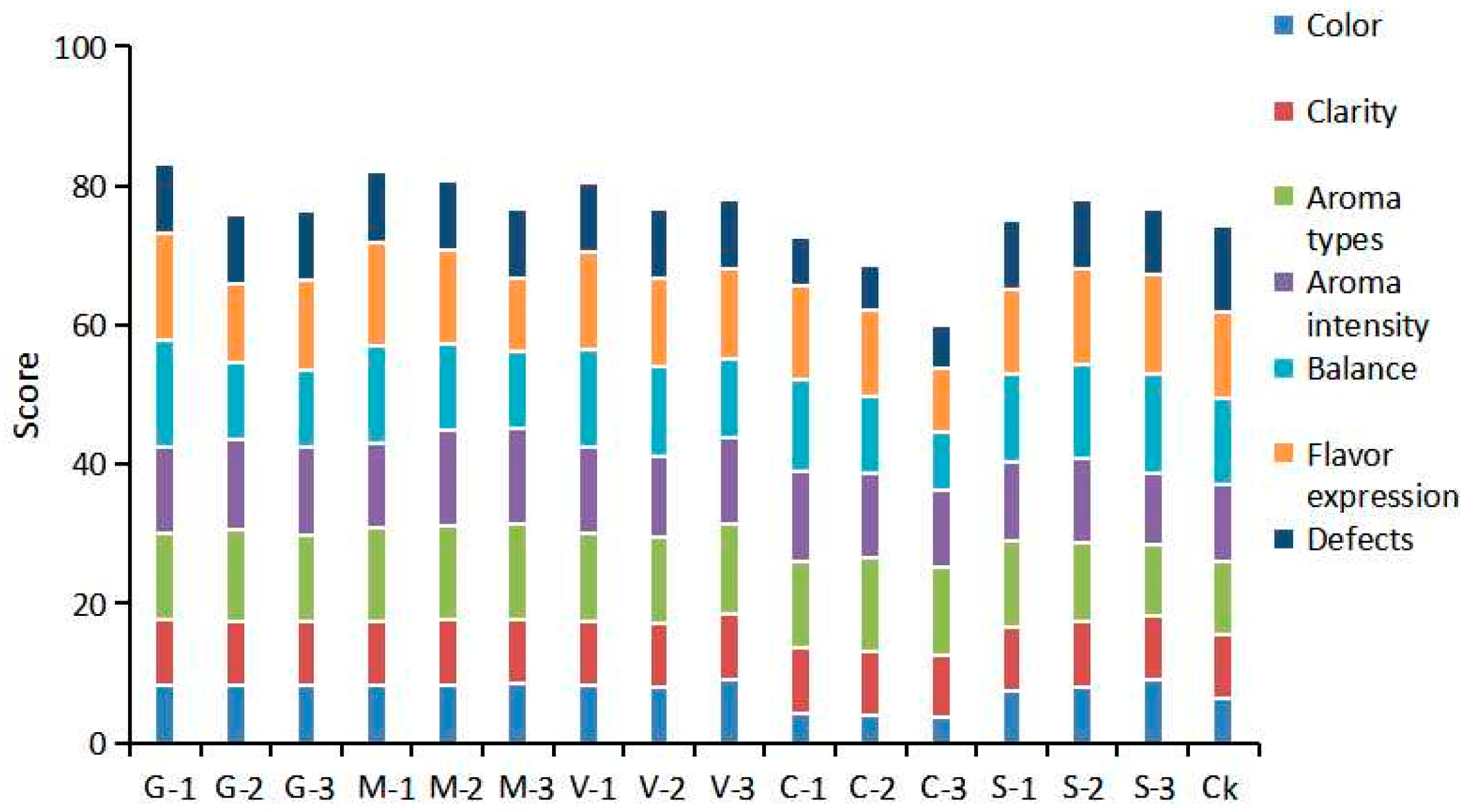

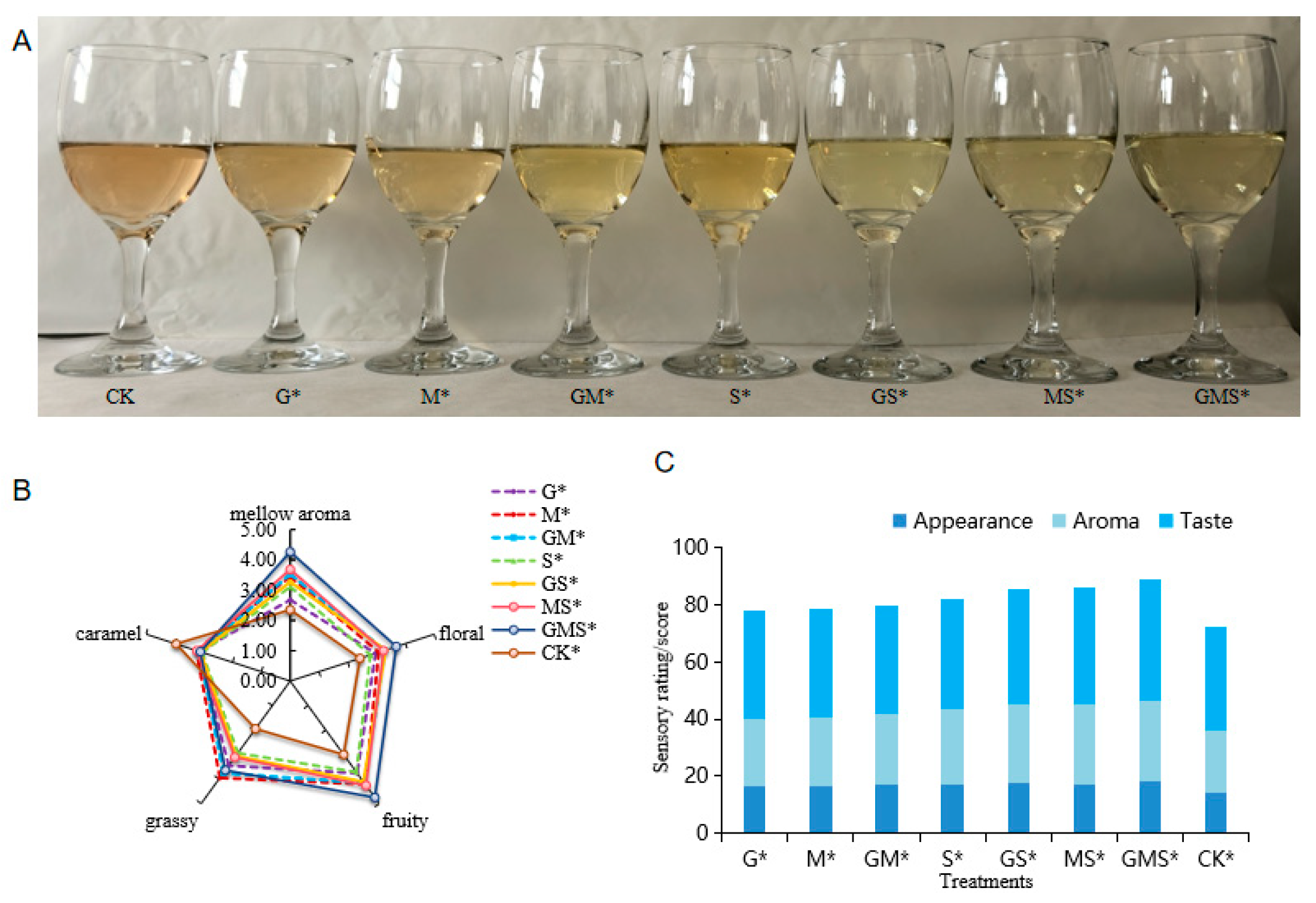

3.2.5. Sensory Evaluation

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GSH | Glutathione |

| Man | Mannan |

| VC | Vitamin C |

| COS | Chitosan oligosaccharide |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- Tarko, T.; Duda-Chodak, A.; Sroka, P.; Siuta, M. The impact of oxygen at various stages of vinification on the chemical composition and the antioxidant and sensory properties of white and red wines. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 1, 7902974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, K.; Dai, X. Safety risks and quality control in huangjiu: From raw materials to fermentation process. Agric. Commun. 2025, 3, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranto, F.; Pasqualone, A.; Mangini, G.; Tripodi, P.; Miazzi, M.M.; Pavan, S.; Montemurro, C. Polyphenol Oxidases in Crops: Biochemical, Physiological and Genetic Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnock, H.M.; Pickering, G.J.; Kemp, B.S. Effect of Amino Acid, Sugar, Ca2+, and Mg2+ on Maillard Reaction-Associated Products in Modified Sparkling Base Wines During Accelerated Aging. Molecules 2025, 30, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, A.M.; Cosme, F. Grapes and Wines: Advances in Production, Processing, Analysis and Valorization; BoD–Books on Demand; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018; ISBN 9535138332. [Google Scholar]

- Barrio-Galán, R.; Nevares, I.; del Alamo-Sanza, M. Characterization and Control of Oxygen Uptake in the Blanketing and Purging of Tanks with Inert Gases in the Winery. Beverages 2023, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.V.A.; Pereira, C.; Martins, N.; Cabrita, M.J.; Gomes Da Silva, M. Different SO2 Doses and the Impact on Amino Acid and Volatile Profiles of White Wines. Beverages 2023, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.; Li, Q.; Xin, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhao, R.; Wang, M.; Xun, L.; Xia, Y. Rhodaneses minimize the accumulation of cellular sulfane sulfur to avoid disulfide stress during sulfide oxidation in bacteria. Redox Biol. 2022, 53, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food Labeling: Sulfite Allergen Labeling Requirements; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1986.

- Federal Register; 2World Health Organization. Safety Evaluation of Certain Food Additives (39th JECFA Report); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/f301e610-8576-469a-bef0-bd30eff52344/content (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Geneva: WHO. 3International Organization of Vine and Wine. Code of Oenological Practices; OIV: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.oiv.int/standards/international-code-of-oenological-practices (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Barril, C.; Rutledge, D.N.; Scollary, G.R.; Clark, A.C. Ascorbic acid and white wine production: A review of beneficial versus detrimental impacts. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2016, 22, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, P.; Just-Borras, A.; Pons, P.; Gombau, J.; Heras, J.M.; Sieczkowski, N.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F. Biotechnological tools for reducing the use of sulfur dioxide in white grape must and preventing enzymatic browning: Glutathione; inactivated dry yeasts rich in glutathione; and bioprotection with Metschnikowia pulcherrima. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.F.; Ribani, R.H.; Stafussa, A.P.; Makara, C.N.; Branco, I.G.; Maciel, G.M.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Exploratory analysis of bioactive compounds and antioxidant potential of grape (Vitis vinifera) pomace. Acta Scientiarum Technol. 2022, 44, e56934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, A.; Palma, M. Sweet Red Wine Production: Effects of Fermentation Stages and Ultrasound Technology on Wine Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellini, A.; Samoggia, A. Millennial consumers’ wine consumption and purchasing habits and attitude towards wine innovation. Wine Econ. Policy 2018, 7, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Guo, J.; Qian, X.; Zhu, B.; Shi, Y.; Wu, G.; Duan, C. Characterization of key odor-active compounds in sweet Petit Manseng (Vitis vinifera L.) wine by gas chromatography–olfactometry, aroma reconstitution, and omission tests. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 1258–1272.1750–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.; Gill Giese, W.; Velasco-Cruz, C.; Lawson, L.; Ma, S.; Wright, M.; Zoecklein, B. Effect of foliar nitrogen and sulfur on petit manseng (Vitis vinifera L.) grape composition. J. Wine Res. 2017, 28, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Del Prado, D.R.; Araujo, L.D.; Quek, S.Y.; Kilmartin, P.A. Effect of glutathione addition at harvest on Sauvignon Blanc wines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2021, 27, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoce, A.O.; Cojocaru, G.A. Sensory profile changes induced by the antioxidant treatments of white wines-the case of glutathione, ascorbic acid and tannin treatments on Feteasca regala wines produced in normal cellar conditions. Agrolife Sci. J. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Guo, Z.; Ma, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhai, H.; Ren, D.; Li, S.; Yi, L. Organoleptic modulation functions and physiochemical characteristics of mannoproteins: Possible correlations and precise applications in modulating color evolution and orthonasal perception of wines. Food Res. Int. 2024, 192, 114803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Marín, A.; Colangelo, D.; Lambri, M.; Riponi, C.; Chinnici, F. Relevance and perspectives of the use of chitosan in winemaking: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 3450–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, W.; Wang, H.; Ma, T.; Li, K.; Wang, B.; Ma, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, B. Enhancing Phenolic Profiles in ‘Cabernet Franc’Grapes Through Chitooligosaccharide Treatments: Impacts on Phenolic Compounds Accumulation Across Developmental Stages. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Chen, F.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Chung, H.Y.; Jin, Z. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of Australian tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil and its components. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2849–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cao, X.; Zhuang, X.; Han, W.; Guo, W.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, X. Rice bran polysaccharides and oligosaccharides modified by Grifola frondosa fermentation: Antioxidant activities and effects on the production of NO. Food Chem. 2017, 223, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, P.; Tomaino, A.; Lo Cascio, R.; Bonina, F.; De Pasquale, A.; Saija, A. Antioxidant effectiveness as influenced by phenolic content of fresh orange juices. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 4718–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wang, Y.; Du, G.; Li, Y. Changes in contents and antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds during gibberellin- induced development in Vitis vinifera L. ‘Muscat’. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 2467–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Gao, H.; Lan, M.; Wang, J.; Dong, Z. Metabolomics and flavor diversity of Viognier wines co-fermented with Saccharomyces cerevisiae from different sources of Metschnikowia pulcherrima strains. J. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard’s GB/T 15038-2006; Analytical Methods of Wine and Fruit Wine. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Andrea-Silva, J.; Cosme, F.; Ribeiro, L.F.; Moreira, A.S.; Malheiro, A.C.; Coimbra, M.A.; Domingues, M.R.M.; Nunes, F.M. Origin of the pinking phenomenon of white wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5651–5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comuzzo, P.; Battistutta, F.; Vendrame, M.; Páez, M.S.; Luisi, G.; Zironi, R. Antioxidant properties of different products and additives in white wine. Food Chem. 2015, 168, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.Z.; Huang, G.Q.; Xu, T.C.; Xu, T.C.; Liu, L.N.; J, X. Comparative study on the Maillard reaction of chitosan oligosaccharide and glucose with soybean protein isolate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xu, J.; Cao, Y.; Qi, Y.; Yang, K.; Wei, X.; Xu, Y.; Fan, M. Effect of glutathione-enriched inactive dry yeast on color, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant activity of kiwi wine. J. Food Process Preserv. 2020, 44, e14347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Casas, M.; Pajaro, M.; Lores, M.; Garcia-Jares, C. Polyphenolic composition and antioxidant activity of Galician monovarietal wines from native and experimental non-native white grape varieties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 2307–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, H. Polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of selected China wines. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonni, F.; Clark, A.C.; Prenzler, P.D.; Riponi, C.; Scollary, G.R. Antioxidant action of glutathione and the ascorbic acid/glutathione pair in a model white wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3940–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguela, J.M.; Teuf, O.; Bicca, S.A.; Vernhet, A. Impact of mannoprotein N-glycosyl phosphorylation and branching on the sorption of wine polyphenols by yeasts and yeast cell walls. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, P.R.; Menezes, L.R.A.; Sassaki, G.L. Structural characterization and physicochemical properties of wine and yeast mannans and evaluation of their interactions with catechin and epicatechin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, F.; Yuan, D.; Yi, L.; Min, Z. Effect of SO2, glutathione, and glutathione-rich inactive dry yeast on the color, phenolic compounds, ascorbic acid, and antioxidant activity of Roxburgh rose wine. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 2814–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buțerchi, I.; Colibaba, L.C.; Luchian, C.E.; Lipșa, F.D.; Ulea, E.; Zamfir, C.I.; Scutarașu, E.C.; Nechita, C.B.; Irimia, L.M.; Cotea, V.V. Impact of Sulfur Dioxide and Dimethyl Dicarbonate Treatment on the Quality of White Wines: A Scientific Evaluation. Fermentation 2025, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, M.P.; Scollary, G.R.; Prenzler, P.D. Examination of the sulfur dioxide–ascorbic acid anti-oxidant system in a model white wine matrix. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, C.; Oliboni, L.S.; Agostini, F.; Funchal, C.; Serafini, L.; Henriques, J.A.; Salvador, M. Phenolic content of grapevine leaves (Vitis labrusca var. Bordo) and its neuroprotective effect against peroxide damage. Toxicol. Vitro 2010, 24, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassetti, D.; Ballabio, D.; Mastro, M.; Tirelli, A.; Jeffery, D.W. Response surface methodology approach to evaluate the effect of transition metals and oxygen on photo-degradation of methionine in a model wine system containing riboflavin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 16347–16357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, P.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; He, I.; Duan, C. The influence of caffeic acid addition before aging on the chromatic quality and phenolic composition of dry red wines. J. Chin. Inst. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 19, 153–160.1009–7848. [Google Scholar]

- Charnock, H.M.; Pickering, G.J.; Kemp, B.S. The Maillard reaction in traditional method sparkling wine. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 979866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temerdashev, Z.A.; Khalafyan, A.A.; Yakuba, Y.F. Comparative assessment of amino acids and volatile compounds role in the formation of wines sensor properties by means of covariation analysis. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhao, M. Six categories of amino acid derivatives with potential taste contributions: A review of studies on soy sauce. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 7981–7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, S.; Su, J.; Tao, Y. Correlation analysis between amino acids and fruity esters during spine grape fermentation. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2020, 53, 2272–2284. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pinilla, O.; Guadalupe, Z.; Hernández, Z.; Ayestarán, B. Amino acids and biogenic amines in red varietal wines: The role of grape variety, malolactic fermentation and vintage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 237, 887–895.s00217–013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procopio, S.; Krause, D.; Hofmann, T.; Becker, T. Significant amino acids in aroma compound profiling during yeast fermentation analyzed by PLS regression. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, X.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, B. Investigation of volatile compounds, microbial succession, and their relation during spontaneous fermentation of Petit Manseng. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 717387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Xu, Y.; An, C.; Peng, B.; Wang, J. Impacts of glutathione-enriched inactive dry yeast preparations on the quality of ‘viognier’ dry white wine. Food Ferment. Ind. 2019, 45, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Alcohol Content (% vol) | pH | Residual Sugar (g/L) | Total Acidity (g/L) | Dry Extract (g/L) | Free Sulfur (mg/L) | Bound Sulfur (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single treatment | 13.0 | 3.1 | 17.7 | 5.3 | 27.7 | 2.2 | 12.0 |

| Combined treatment | 12.0 | 3.2 | 17.5 | 5.1 | 27.3 | 1.7 | 13.2 |

| Treatment Code | Treatment Method |

|---|---|

| CK | Distilled water blank |

| G-1 | 10 mg/L GSH |

| G-2 | 20 mg/L GSH |

| G-3 | 30 mg/L GSH |

| M-1 | 10 mg/L Man |

| M-2 | 20 mg/L Man |

| M-3 | 30 mg/L Man |

| V-1 | 50 mg/L VC |

| V-2 | 100 mg/L VC |

| V-3 | 200 mg/L VC |

| C-1 | 50 mg/L COS |

| C-2 | 100 mg/L COS |

| C-3 | 200 mg/L COS |

| S-1 | 10 mg/L SO2 |

| S-2 | 20 mg/L SO2 |

| S-3 | 30 mg/L SO2 |

| CK* | Distilled water blank |

| G* | 10 mg/L GSH |

| M* | 10 mg/L Man |

| GM* | 10 mg/L GSH and 10 mg/L Man |

| S* | 20 mg/L SO2 |

| GS* | 10 mg/L GSH and 20 mg/L SO2 |

| MS* | 10 mg/L Man and 20 mg/L SO2 |

| GMS* | 5 mg/L GSH, 5 mg/L Man and 20 mg/L SO2 |

| Chemical Substance | Concentration (µg/L) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK* | G* | M* | GM* | S* | GS* | MS* | GMS* | |

| Caffeic acid | 1217.5 ± 50.8 f | 1594.6 ± 281.9 d | 1500.3 ± 129.7 d | 1479.2 ± 47.1 d | 3443.3 ± 543.9 c | 4058.2 ± 197.5 ab | 3889.2 ± 214.1 b | 4265.8 ± 111.3 a |

| Gallic acid | 356.0 ± 26.3 f | 394.2 ± 8.4 f | 1078.0 ± 102.1 e | 2115.8 ± 22.4 d | 2527.4 ± 457.2 c | 3018.9 ± 283.6 a | 2699.2 ± 230.7 b | 3089.9 ± 289.7 a |

| Coumaric acid | 278.1 ± 9.1 b | 278.5 ± 19.1 b | 278.0 ± 10.2 b | 272.8 ± 10.7 b | 416.3 ± 36.2 a | 427.9 ± 28.6 a | 424.2 ± 24.2 a | 459.1 ± 31.1 a |

| Gallocatechin | 213.3 ± 10.3 d | 209.4 ± 21.9 d | 372.1 ± 18.3 c | 411.3 ± 31.2 b | 368.4 ± 39.4 c | 427.7 ± 42.1 b | 543.8 ± 44.3 a | 567.4 ± 36.4 a |

| Vanillic acid | 177.5 ± 13.2 a | 179.1 ± 5.3 a | 185.9 ± 6.3 a | 180.3 ± 3.6 a | 189.3 ± 4.3 a | 179.9 ± 9.1 a | 185.8 ± 2.4 a | 180.3 ± 10.3 a |

| Ferulic acid | 158.8 ± 2.8 d | 171.4 ± 11.2 d | 167.3 ± 8.4 d | 167.7 ± 3.2 d | 229.6 ± 15.2 c | 231.1 ± 7.1 bc | 236.5 ± 7.1 ab | 247.1 ± 5.9 a |

| Syringic acid | 150.1 ± 2.9 b | 149.1 ± 3.4 b | 150.3 ± 3.1 b | 151.9 ± 1.2 b | 170.9 ± 5.1 a | 167.6 ± 3.9 a | 170.1 ± 5.9 a | 171.7 ± 2.2 a |

| Salicylic acid | 147.1 ± 6.2 b | 153.5 ± 1.7 ab | 150.4 ± 6.3 ab | 151.7 ± 6.4 ab | 160.4 ± 2.2 a | 155.1 ± 5.1 ab | 160.6 ± 0.6 a | 161.4 ± 1.5 a |

| Catechin | 117.7 ± 14.5 d | 147.6 ± 32.2 c | 128.8 ± 10.5 cd | 136.6 ± 12.9 c | 531.6 ± 214.5 b | 672.2 ± 69.6 a | 558.4 ± 41.1 b | 663.5 ± 58.4 a |

| Epicatechin | 108.1 ± 10.2 f | 166.2 ± 40.1 d | 137.4 ± 13.6 d | 145.4 ± 8.1 d | 570.4 ± 0.6 c | 730.1 ± 75.4 a | 610.6 ± 51.1 b | 738.2 ± 52.6 a |

| Resveratrol 3-O-glucoside | 103.4 ± 1.8 c | 104.4 ± 11.7 c | 107.5 ± 5.2 c | 105.1 ± 2.7 c | 153.2 ± 9.9 a | 133.7 ± 13.4 b | 127.9 ± 9.1 b | 140.5 ± 17.1 ab |

| Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | 71.3 ± 0.2 b | 71.2 ± 0.4 b | 71.1 ± 0.5 b | 71.2 ± 0.3 b | 72.2 ± 0.9 a | 69.7 ± 0.5 c | 69.1 ± 0.6 c | 70.1 ± 0.4 bc |

| Epigallocatechin | 36.2 ± 3.7 d | 42.8 ± 9.5 cd | 45.3 ± 1.6 c | 39.7 ± 6.1 cd | 72.1 ± 4.5 b | 122.9 ± 16.3 a | 74.7 ± 15.7 b | 119.1 ± 12.6 a |

| Petunidin-3-O-glucoside | 32.1 ± 0.5 a | 32.1 ± 1.1 a | 32.5 ± 0.2 a | 31.9 ± 0.6 a | 32.3 ± 0.6 a | 32.3 ± 0.7 a | 32.4 ± 0.4 a | 31.6 ± 0.3 a |

| Procyanidin B1 | 17.9 ± 0.6 c | 22.1 ± 0.6 c | 18.7 ± 2.1 c | 19.8 ± 2.2 c | 142.7 ± 10.2 ab | 149.0 ± 10.7 a | 97.4 ± 7.1 b | 146.9 ± 26.5 ab |

| Resveratrol | 13.5 ± 0.1 b | 13.7 ± 0.1 a | 13.5 ± 0.1 b | 13.7 ± 0.1 a | 13.6 ± 0.1 a | 13.8 ± 0.1 a | 13.5 ± 0.1 a | 13.7 ± 0.4 ab |

| Epicatechin gallate | 6.1 ± 0.3 a | 4.9 ± 0.2 b | 4.6 ± 0.1 b | 4.6 ± 0.1 b | 5.8 ± 1.2 ab | 4.7 ± 0.2 b | 4.6 ± 0.1 b | 4.3 ± 0.1 c |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | 1.2 ± 0.2 a | 1.1 ± 0.1 a | 1.1 ± 0.1 a | 1.1 ± 0.1 a | 1.1 ± 0.1 a | 1.1 ± 0.1 a | 1.1 ± 0.1 a | 1.1 ± 0.1 a |

| Chemical Substance | Concentration (mg/L) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK* | G* | M* | GM* | S* | GS* | MS* | GMS* | |

| Prolin | 2691.1 ± 338.5 ab | 2353.1 ± 287.1 b | 2671.1 ± 299.1 ab | 2444.2 ± 228.4 b | 2558.6 ± 109.2 ab | 2547.5 ± 150.8 b | 2733.6 ± 285.7 ab | 2777.3 ± 222.1 a |

| Arginin | 110.3 ± 3.3 b | 107.8 ± 4.9 b | 112.2 ± 3.4 ab | 110.5 ± 3.4 b | 111.3 ± 2.8 b | 114.4 ± 2.9 ab | 116.5 ± 0.6 a | 112.1 ± 3.5 ab |

| G-aminobutyric acid | 81.1 ± 2.4 a | 80.4 ± 3.2 a | 84.7 ± 2.5 a | 84.2 ± 2.5 a | 84.5 ± 1.8 a | 82.1 ± 2.1 a | 83.6 ± 0.8 a | 81.1 ± 2.4 a |

| Alanin | 39.6 ± 1.3 a | 39.4 ± 1.6 a | 41.6 ± 1.2 a | 41.3 ± 1.2 a | 41.4 ± 0.9 a | 40.3 ± 1.0 a | 41.1 ± 1.2 a | 40.1 ± 1.4 a |

| Valin | 29.4 ± 1.1 ab | 29.2 ± 1.1 ab | 30.8 ± 0.8 a | 30.2 ± 0.8 a | 30.5 ± 0.6 a | 29.3 ± 0.9 ab | 29.8 ± 0.3 ab | 28.6 ± 0.9 b |

| Glutamic acid | 27.1 ± 0.8 a | 27.1 ± 1.1 a | 28.2 ± 0.9 a | 28.1 ± 0.9 a | 28.2 ± 0.6 a | 28.2 ± 0.7 a | 28.8 ± 0.2 a | 27.9 ± 0.8 a |

| β-Alanin | 23.2 ± 0.6 a | 23.1 ± 0.8 a | 24.3 ± 0.7 a | 24.2 ± 0.7 a | 24.2 ± 0.5 a | 23.8 ± 0.6 a | 24.3 ± 0.7 a | 23.6 ± 0.6 a |

| Lysin | 22.3 ± 1.1 a | 22.3 ± 1.4 a | 23.7 ± 0.3 a | 23.9 ± 1.3 a | 23.8 ± 0.4 a | 23.2 ± 0.8 a | 23.7 ± 0.8 a | 22.8 ± 0.7 a |

| Ornithin | 14.4 ± 0.3 ab | 14.1 ± 0.7 b | 14.7 ± 0.4 ab | 14.9 ± 0.5 ab | 14.8 ± 0.1 ab | 14.8 ± 0.6 ab | 15.2 ± 0.6 a | 14.5 ± 0.2 ab |

| Aspartic acid | 14.2 ± 1.5 a | 14.4 ± 1.4 a | 15.1 ± 1.2 a | 13.6 ± 1.2 a | 14.3 ± 2.1 a | 15.1 ± 0.9 a | 15.7 ± 1.4 a | 14.4 ± 1.3 a |

| Leucin | 13.8 ± 0.4 a | 13.8 ± 0.5 a | 14.6 ± 0.4 a | 14.6 ± 0.4 a | 14.6 ± 0.3 a | 14.1 ± 0.3 a | 14.4 ± 0.1 a | 14.1 ± 0.4 a |

| Asparagin | 13.2 ± 0.3 a | 13.2 ± 0.4 a | 13.8 ± 0.4 a | 13.8 ± 0.4 a | 13.8 ± 0.3 a | 13.6 ± 0.3 a | 13.9 ± 0.1 a | 13.6 ± 0.4 a |

| Glycin | 12.1 ± 0.1 b | 12.1 ± 0.3 b | 12.6 ± 0.4 ab | 12.6 ± 0.4 ab | 12.6 ± 0.3 a | 12.6 ± 0.3 a | 12.9 ± 0.1 a | 12.5 ± 0.3 ab |

| Histidin | 11.1 ± 0.5 b | 11.1 ± 0.6 b | 11.3 ± 0.4 b | 11.3 ± 0.4 b | 11.3 ± 0.3 ab | 13.3 ± 0.3 a | 12.1 ± 0.8 ab | 12.1 ± 0.4 ab |

| Glutamin | 10.4 ± 0.3 c | 10.4 ± 0.4 c | 11.1 ± 0.3 b | 11.1 ± 0.3 b | 11.1 ± 0.2 b | 12.1 ± 0.2 a | 10.6 ± 0.3 c | 10.9 ± 0.3 c |

| Phenylalanin | 9.9 ± 0.3 a | 10.0 ± 0.4 a | 10.6 ± 0.3 a | 10.5 ± 0.2 a | 10.5 ± 0.2 a | 10.2 ± 0.1 a | 10.5 ± 0.2 a | 10.2 ± 0.2 a |

| Tyrosin | 9.1 ± 0.3 a | 9.1 ± 0.4 a | 9.6 ± 0.3 a | 9.5 ± 0.3 a | 9.5 ± 0.2 a | 9.4 ± 0.1 a | 9.6 ± 0.3 a | 9.3 ± 0.2 a |

| Serin | 6.6 ± 0.2 b | 6.7 ± 0.2 b | 7.1 ± 0.1 a | 7.0 ± 0.1 a | 7.1 ± 0.1 a | 6.9 ± 0.1 a | 7.2 ± 0.1 a | 7.0 ± 0.1 a |

| Methionin | 5.3 ± 1.2 b | 6.1 ± 1.2 ab | 6.5 ± 0.4 a | 4.6 ± 0.4 b | 5.6 ± 1.4 ab | 4.7 ± 1.6 b | 5.2 ± 1.7 ab | 4.2 ± 1.2 b |

| Threonin | 3.1 ± 0.3 b | 3.4 ± 0.3 ab | 3.4 ± 0.1 ab | 3.5 ± 0.1 a | 3.4 ± 0.1 ab | 3.4 ± 0.1 ab | 3.4 ± 0.1 ab | 3.4 ± 0.1 ab |

| Isoleucin | 2.6 ± 0.1 a | 2.7 ± 0.1 a | 2.8 ± 0.1 a | 2.8 ± 0.1 a | 2.8 ± 0.1 a | 2.7 ± 0.1 a | 2.8 ± 0.1 a | 2.8 ± 0.1 a |

| Retention Time | Volatile Chemical Substances | Concentration (µg/L) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK* | G* | M* | GM* | S* | GS* | MS* | GMS* | ||

| 3.93 | Isoamyl alcohol | 1390.4 ± 214.2 ab | 1026.5 ± 109.2 d | 1388.2 ± 108.9 b | 1453.3 ± 217.3 a | 1346.2 ± 37.9 b | 1488.3 ± 27.4 a | 1395.1 ± 79.2 ab | 1227 ± 73.2 c |

| 5.5 | 2,3-Butanediol | 35.4 ± 8.2 a | 20.1 ± 2.1 b | 18.5 ± 2.8 bc | 21.4 ± 3.8 b | 13.5 ± 1.1 cd | 14.7 ± 2.c | 12.8 ± 1.2 d | 15.3 ± 1.2 c |

| 5.75 | n-Pentanol | 31.4 ± 2.3 d | 54.8 ± 2.9 c | 62.4 ± 1.3 b | 60.5 ± 3.8 b | 72.5 ± 3.1 a | 68.4 ± 1.5 b | 75.2 ± 2.7 a | 69.5 ± 0.8 b |

| 7.75 | n-Hexanol | 194.6 ± 13.9 e | 264.8 ± 14.3 d | 276.8 ± 8.4 d | 288.4 ± 15.2 d | 425.9 ± 13.7 a | 395.1 ± 9.3 c | 468.5 ± 21.3 a | 421.5 ± 11.9 b |

| 14.43 | Cyclohexanol | 2.6 ± 1.8 e | 10.6 ± 1.8 d | 14.2 ± 1.8 c | 12.9 ± 2.1 d | 12.4 ± 1.1 d | 18.1 ± 1.8 b | 22.6 ± 2.3 a | 17.8 ± 2.1 b |

| 16.89 | n-Octanol | 16.8 ± 1.3 e | 18.6 ± 2.3 de | 20.5 ± 1.1 d | 21.5 ± 0.4 d | 32.7 ± 2.9 b | 28.5 ± 1.7 bc | 36.8 ± 2.3 a | 30.7 ± 2.8 bc |

| 18.85 | Phenylethyl alcohol | 91.8 ± 3.4 a | 66.4 ± 3.2 b | 45.6 ± 2.1 d | 58.2 ± 3.1 c | 58.3 ± 2.1 c | 34.3 ± 2.1 e | 58.5 ± 2.9 c | 44.6 ± 2.1 d |

| 26.37 | n-Decanol | 7.4 ± 0.3 d | 24.4 ± 1.2 bc | 24.2 ± 2.1 bc | 22.3 ± 1.1 c | 26.3 ± 2.1 b | 31.5 ± 1.9 a | 31.9 ± 0.3 a | 32.5 ± 1.2 a |

| 2.28 | Ethyl acetate | 318.2 ± 1.3 e | 420.7 ± 5.9 d | 518.3 ± 21.8 c | 687.4 ± 15.3 a | 574.1 ± 30.2 b | 308.1 ± 15.3 e | 558.4 ± 12.4 b | 578 ± 3.8 b |

| 3.43 | Ethyl propionate | 32.8 ± 2.8 d | 50.6 ± 5.9 c | 48.7 ± 3.8 c | 52.5 ± 3.8 c | 67.6 ± 3.1 b | 72.8 ± 2.1 a | 71.7 ± 1.4 a | 66.8 ± 2.2 b |

| 4.62 | Isobutyl acetate | 20.7 ± 2.3 e | 12.5 ± 3.2 f | 50.2 ± 2.7 c | 38.9 ± 2.1 d | 65.1 ± 3.2 b | 56.4 ± 3.1 c | 70.7 ± 2.1 a | 65.2 ± 2.1 b |

| 5.32 | Ethyl butyrate | 120.9 ± 13.8 e | 233.5 ± 15.9 c | 239.5 ± 11.9 c | 155.4 ± 7.3 d | 354.2 ± 3.9 b | 359.2 ± 3.5 b | 472.1 ± 15.2 a | 350.1 ± 8.3 b |

| 7.01 | Isoamyl valerate | 2.6 ± 0.3 bc | 1.9 ± 0.1 d | 2.2 ± 0.2 c | 2.3 ± 0.1 c | 3.2 ± 0.1 c | 3.7 ± 0.2 a | 3.6 ± 1.1 a | 3.3 ± 1.3 b |

| 7.9 | Isoamyl acetate | 1529.2 ± 34.8 e | 1811.5 ± 104.2 d | 2210.5 ± 207.2 c | 1880.7 ± 128.8 d | 2253.6 ± 117.3 c | 2524.2 ± 47.1 b | 3297.3 ± 142.8 a | 3352.1 ± 231.2 a |

| 9.35 | Amyl acetate | 0.8 ± 0.2 d | 0.8 ± 0.3 d | 1.2 ± 0.1 d | 1.1 ± 0.2 d | 3.0 ± 0.2 a | 1.8 ± 0.1 c | 2.3 ± 0.2 b | 1.8 ± 0.2 c |

| 12.35 | 3-Methyl amyl acetate | 5.6 ± 0.1 b | 4.1 ± 0.1 e | 4.6 ± 0.1 d | 5.2 ± 0.1 c | 5.3 ± 0.1 bc | 6.6 ± 0.15 a | 5.7 ± 0.2 b | 5.6 ± 0.1 b |

| 13.83 | Hexyl acetate | 555.1 ± 34.1 d | 928.7 ± 104.2 c | 1071.2 ± 73.2 b | 900.1 ± 25.3 c | 1335.8 ± 74.1 a | 1334.6 ± 109.0 a | 1276.6 ± 134.3 a | 1225.6 ± 93.2 a |

| 15.89 | Isoamyl butyrate | 2.5 ± 0.1 b | 1.8 ± 0.1 c | 2.2 ± 0.2 c | 2.6 ± 0.1 b | 3.2 ± 0.1 ab | 3.9 ± 0.1 a | 3.7 ± 0.1 a | 3.6 ± 0.2 a |

| 17.91 | Ethyl heptanoate | 1.2 ± 0.1 a | 0.7 ± 0.1 c | 0.9 ± 0.1 b | 1.1 ± 0.1 b | 0.9 ± 0.1 b | 1.3 ± 0.1 a | 0.9 ± 0.1 b | 0.8 ± 0.1 bc |

| 20.44 | Isobutyl hexanoate | 2.2 ± 0.1 e | 3.2 ± 0.1 d | 3.6 ± 0.1 c | 3.9 ± 0.1 c | 4.4 ± 0.1 b | 5.7 ± 0.1 a | 4.4 ± 0.1 b | 4.4 ± 0.1 b |

| 22.82 | Ethyl octanoate | 5682.3 ± 538.9 g | 7043.2 ± 338.2 f | 7603.1 ± 834.1 f | 9107.5 ± 593.1 e | 17,839.1 ± 398.3 c | 199,028.3 ± 903.2 a | 13,961.2 ± 739.3 d | 157,220 ± 1098.3 b |

| 25.11 | Isoamyl hexanoate | 51.8 ± 5.9 c | 80.1 ± 5.9 d | 90.2 ± 9.3 b | 81.7 ± 3.9 c | 99.4 ± 4.9 b | 111.1 ± 3.8 a | 109.3 ± 7.9 a | 108.9 ± 6.1 ab |

| 25.38 | Phenethyl acetate | 25.2 ± 2.9 e | 42.1 ± 3.3 d | 25.1 ± 3.3 e | 28.6 ± 3.9 e | 80.2 ± 2.9 a | 55.9 ± 3.9 c | 74.7 ± 2.7 b | 75.5 ± 3.2 b |

| 27.04 | Propyl octanoate | 2.7 ± 0.2 c | 3.5 ± 0.1 b | 3.8 ± 0.2 b | 3.9 ± 0.7 b | 4.6 ± 0.2 a | 4.7 ± 0.2 a | 5.2 ± 0.3 a | 4.5 ± 0.3 ab |

| 27.21 | Ethyl nonanoate | 6.3 ± 0.3 e | 10.3 ± 0.7 c | 8.6 ± 1.1 d | 1.9 ± 0.1 f | 13.5 ± 1.2 b | 13.2 ± 0.3 b | 15.2 ± 0.9 a | 12.8 ± 0.8 b |

| 28.46 | Methyl decanoate | 5.6 ± 0.9 e | 10.4 ± 0.2 c | 8.2 ± 0.3 d | 10.7 ± 0.4 c | 14.6 ± 0.2 a | 13.1 ± 0.3 ab | 12.2 ± 0.2 b | 13.7 ± 0.7 a |

| 29.96 | Ethyl 9-decenoate | 264.5 ± 23.9 f | 585.1 ± 38.1 e | 650.1 ± 76.2 d | 655.3 ± 33.7 d | 764.9 ± 23.9 c | 861.7 ± 29.3 b | 994.6 ± 39.2 a | 813.8 ± 34.9 b |

| 31.72 | Ethyl decanoate | 12,272.1 ± 428.3 d | 15,043.2 ± 38.9 b | 15,275.2 ± 870.6 b | 15,092.3 ± 637.3 b | 16,425.8 ± 398.2 a | 15,443.9 ± 329.2 b | 14,275.5 ± 378.1 c | 14,271.3 ± 398.2 c |

| 33.64 | Isoamyl octanoate | 61.6 ± 12.9 a | 15.6 ± 2.9 b | 15.6 ± 0.3 c | 16.4 ± 1.9 b | 13.4 ± 1.2 b | 14.6 ± 0.8 bc | 11.1 ± 0.3 d | 11.2 ± 1.2 d |

| 35.15 | Ethyl 9-hexadecenoate | 6.4 ± 0.4 c | 11.21 ± 0.35 a | 10.6 ± 0.7 b | 8.2 ± 0.3 b | 12.7 ± 1.1 a | 12.3 ± 0.3 a | 12.0 ± 0.7 a | 12.0 ± 0.5 a |

| 35.37 | n-Propyl decanoate | 0.4 ± 0.1 c | 0.6 ± 0.1 a | 0.6 ± 0.1 a | 0.7 ± 0.1 a | 0.7 ± 0.1 a | 0.5 ± 0.1 ab | 0.7 ± 0.1 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 a |

| 37.29 | Isobutyl decanoate | 0.2 ± 0.1 d | 1.5 ± 0.1 c | 1.9 ± 0.1 b | 2.4 ± 0.2 a | 1.9 ± 0.1 b | 1.8 ± 0.1 b | 1.3 ± 0.1 c | 1.3 ± 0.1 c |

| 37.54 | Ethyl myristate | 0.5 ± 0.1 d | 1.3 ± 0.1 cd | 2.2 ± 0.1 b | 2.8 ± 0.1 a | 3.1 ± 0.1 a | 2.6 ± 0.1 ab | 1.7 ± 0.1 c | 0.9 ± 0.1 d |

| 37.88 | Ethyl palmitate | 1.1 ± 0.1 c | 3.7 ± 0.1 a | 3.5 ± 0.2 a | 3.6 ± 0.2 a | 3.1 ± 0.3 ab | 3.5 ± 0.3 a | 2.8 ± 0.1 b | 2.5 ± 0.3 b |

| 38.91 | Ethyl laurate | 1103.1 ± 74.2 c | 1525.6 ± 105.3 a | 1426.7 ± 78.1 a | 1516.1 ± 78.1 a | 1417.4 ± 78.2 ab | 1389.4 ± 107.2 b | 1298.7 ± 78.8 b | 1435.2 ± 36.9 a |

| 40.52 | 3-Methylbutyl decanoate | 6.9 ± 02 b | 4.6 ± 0.6 c | 6.3 ± 0.2 b | 9.1 ± 0.2 a | 7.1 ± 0.3 b | 6.7 ± 0.1 b | 4.6 ± 0.7 c | 4.9 ± 0.3 c |

| 24.56 | Octanoic acid | 6.2 ± 0.2 a | 4.7 ± 0.3 b | 3.7 ± 0.1 bc | 2.2 ± 0.1 cd | 2.6 ± 0.1 c | 2.3 ± 0.1 c | 2.9 ± 0.1 c | 1.8 ± 0.1 d |

| 32.64 | Decanoic acid | 5.4 ± 0.1 a | 3.8 ± 0.1 b | 3.2 ± 0.1 b | 2.1 ± 0.3 bc | 1.8 ± 0.1 c | 3.1 ± 0.2 b | 2.9 ± 0.1 b | 2.7 ± 0.1 b |

| 1.68 | Acetaldehyde | 71.4 ± 2.9 a | 54.5 ± 3.9 b | 46.4 ± 5.1 b | 50.8 ± 2.3 b | 40.8 ± 5.9 bc | 35.2 ± 4.2 c | 32.6 ± 7.24 c | 28.1 ± 2.2 d |

| 3.64 | Acetal | 122.1 ± 11.8 a | 45.7 ± 4.3 c | 74.7 ± 4.2 b | 75.2 ± 2.9 b | 51.6 ± 5.3 c | 44.3 ± 3.2 c | 51.1 ± 5.2 c | 40.2 ± 5.2 c |

| 19.18 | Benzaldehyde | 15.5 ± 2.1 a | 10.6 ± 1.2 b | 9.6 ± 1.1 b | 12.6 ± 2.3 a | 5.4 ± 0.3 c | 4.2 ± 0.7 c | 3.5 ± 0.3 c | 4.8 ± 0.2 c |

| 13.05 | Linalool | 10.3 ± 3.2 a | 2.2 ± 0.1 c | 1.8 ± 0.3 a | 2.2 ± 0.7 b | 2.1 ± 0.2 b | 1.7 ± 0.1 b | 2.2 ± 0.3 b | 1.8 ± 0.1 b |

| 30.65 | Damascenone | 32.1 ± 1.2 a | 16.5 ± 1.1 b | 12.2 ± 1.2 b | 15.3 ± 2.1 b | 14.4 ± 0.2 b | 12.8 ± 1.2 c | 10.7 ± 0.3 c | 11.5 ± 1.2 c |

| 33.64 | 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol | 3.9 ± 0.1 a | 1.8 ± 0.1 b | 1.6 ± 0.1 b | 1.1 ± 0.1 c | 1.1 ± 0.1 c | 0.5 ± 0.1 d | 0.7 ± 0.1 c | 0.8 ± 0.1 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Tang, P.; Wang, C.; Ye, S.; Xiao, F.; Luo, X.; Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Ji, W.; Dong, Z.; et al. The Impact of Sulfite Reduction Alternatives with Various Antioxidants on the Quality of Semi-Sweet Wines. Foods 2026, 15, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010053

Liu Z, Tang P, Wang C, Ye S, Xiao F, Luo X, Wang J, Lu J, Ji W, Dong Z, et al. The Impact of Sulfite Reduction Alternatives with Various Antioxidants on the Quality of Semi-Sweet Wines. Foods. 2026; 15(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhenghai, Ping Tang, Chenyu Wang, Shaosong Ye, Feng Xiao, Xueru Luo, Jun Wang, Jiang Lu, Wei Ji, Zhigang Dong, and et al. 2026. "The Impact of Sulfite Reduction Alternatives with Various Antioxidants on the Quality of Semi-Sweet Wines" Foods 15, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010053

APA StyleLiu, Z., Tang, P., Wang, C., Ye, S., Xiao, F., Luo, X., Wang, J., Lu, J., Ji, W., Dong, Z., & Zhao, Q. (2026). The Impact of Sulfite Reduction Alternatives with Various Antioxidants on the Quality of Semi-Sweet Wines. Foods, 15(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010053