1. Introduction

The global demand for sustainable, health-conscious, and allergen-friendly foods has accelerated the development of plant-based dairy alternatives, with yogurt alternatives made from plant proteins becoming increasingly popular [

1]. These products offer numerous advantages, including lower environmental impact, compatibility with vegan and lactose-intolerant diets, and high nutritional value from legumes, seeds, and grains such as soy, pea, chickpea, mung bean, fava bean, hemp, rice, and barley [

2]. Despite their promise, the commercial success of plant-based yogurt alternatives remains hindered by persistent issues with off-odors that negatively affect consumer acceptance [

3].

These off-odors, often described as beany, grassy, earthy, sulfurous, or cereal-like, originate from a diverse array of volatile compounds that are either inherent to plant materials during cultivation or formed during processing, extraction, or storage and are influenced by both enzymatic and non-enzymatic pathways [

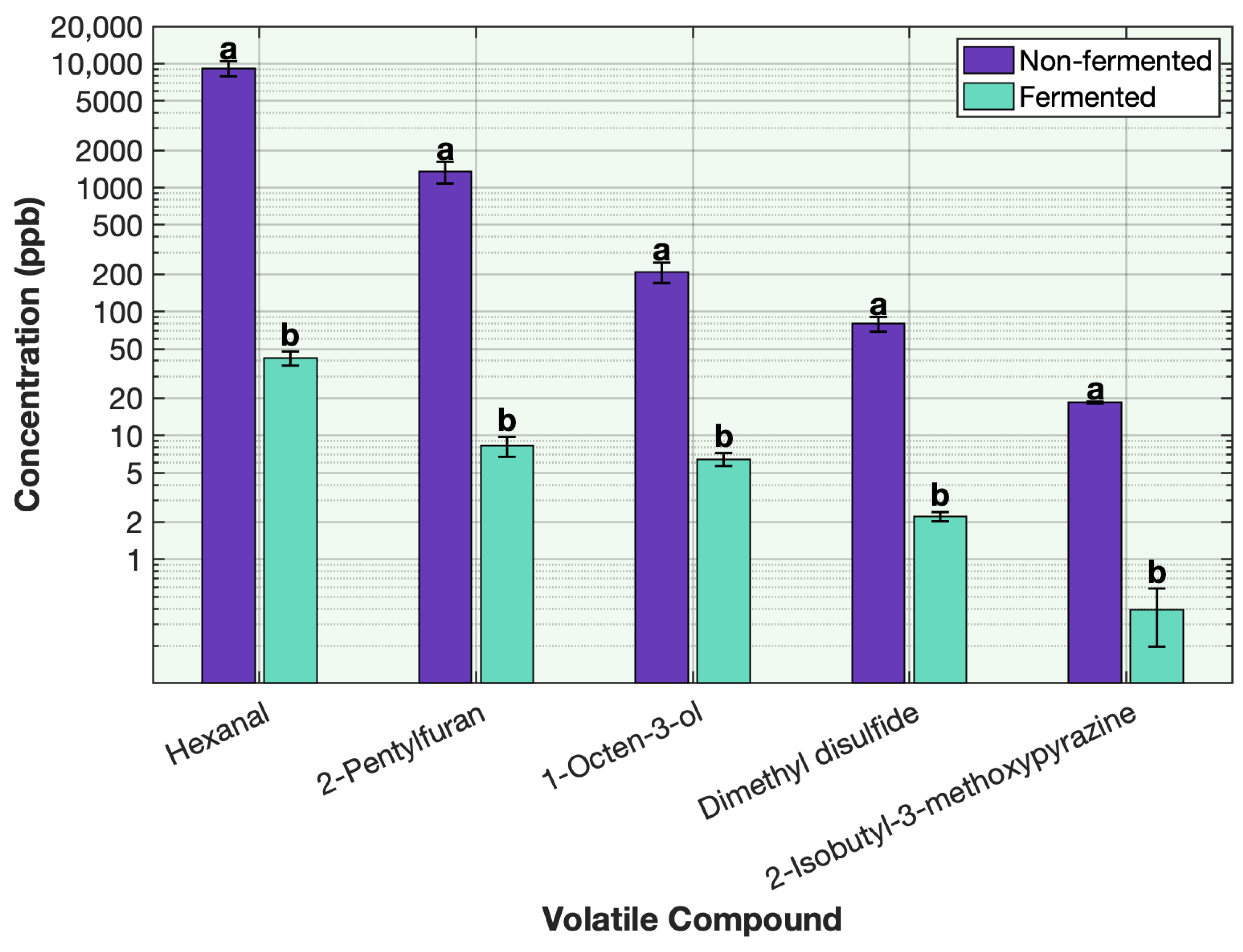

3]. Among the volatile compounds responsible are aldehydes (e.g., hexanal, pentanal, nonanal), alcohols (e.g., 1-hexanol, 1-octen-3-ol), ketones (e.g., 2-heptanone), furans (e.g., 2-pentylfuran), pyrazines, and sulfur-containing volatiles (e.g., dimethyl disulfide, dimethyl trisulfide, hydrogen sulfide) [

4].

Each plant protein contributes its own specific profile of off-odors. Soy and pea proteins are commonly associated with aldehydes such as hexanal, heptanal, nonanal, and pentanal, primarily derived from oxidative degradation of unsaturated fatty acids via the lipoxygenase pathway [

4]. These aldehydes impart strong green, grassy, and fatty odors [

4]. Chickpea, mung bean, and fava bean proteins also contain these aldehydes, but additionally produce methoxypyrazines such as 2-isobutyl-3-methoxypyrazine and 2-isopropyl-3-methoxypyrazine, which contribute earthy, pea-like, and pungent off-odors [

4,

5]. Hemp protein, due to its high lipid and sulfur amino acid content, often releases 1-octen-3-ol, 1-octen-3-one, octanal, decanal, and sulfurous compounds such as dimethyl trisulfide and hydrogen sulfide, resulting in musty, mushroom-like, or burnt rubber odors [

4,

5]. Rice proteins, while generally more neutral, still contribute off-notes from 1-hexanol, which can smell starchy, sweet-green, or cereal-like [

5,

6]. In addition to aldehydes and alcohols, other problematic volatiles include nitrogen and sulfur compounds, which are typically formed through amino acid degradation [

4,

5].

Extensive efforts have been made to mitigate these off-odors, ranging from breeding low-lipoxygenase varieties to thermal and chemical treatments [

4]. However, these approaches often fall short. Thermal processing can denature proteins and alter texture, while chemical extraction may strip nutritional components or violate clean label expectations [

4]. Most critically, these methods often target only a subset of volatiles or fail to eliminate bound compounds that release unpleasant aromas during storage or rehydration [

4]. Fermentation has emerged as a natural and multifunctional strategy to reduce off-odor volatiles while enhancing sensory properties and probiotic value [

4,

7,

8]. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are known for metabolizing undesirable aldehydes, sulfur volatiles, and short-chain amines into less odorous compounds or masking them with the production of pleasant acidic or fruity notes [

8]. However, previous studies have typically relied on single-stage fermentation, with different lactic acid bacteria [

8,

9,

10,

11]. While effective in some cases, this approach may lack the enzymatic diversity needed to neutralize a broad spectrum of off-odor-producing volatile compounds, as each bacterial strain produces a distinct set of enzymes that target specific volatile compounds.

The potential of a sequential fermentation strategy, employing different microbial cultures at different stages to broaden deodorization capacity, remains underexplored. To address this gap, the present study investigates a two-stage microbial fermentation approach designed to reduce off-odor volatiles across a range of plant protein bases. In the first stage, L. plantarum is employed for its capacity to degrade aldehydes, amines, and sulfur-containing compounds. In the second stage, a traditional yogurt starter culture comprising Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, and Lactobacillus acidophilus are added to further modulate aroma and develop desirable yogurt-like sensory characteristics. This combination leverages the complementary metabolic activities of both microbial groups by the robust deodorizing potential of L. plantarum, followed by the flavor-enhancing and odor-reducing functions of the standard yogurt cultures. We hypothesize that this sequential fermentation will be more effective at reducing a broad spectrum of off-odor volatile compounds in plant proteins. Sequential fermentation will work better than fermentation with both cultures co-inoculated in a single-step fermentation. This improved efficacy is expected due to the stepwise deodorization of off-odor-producing volatile compounds.

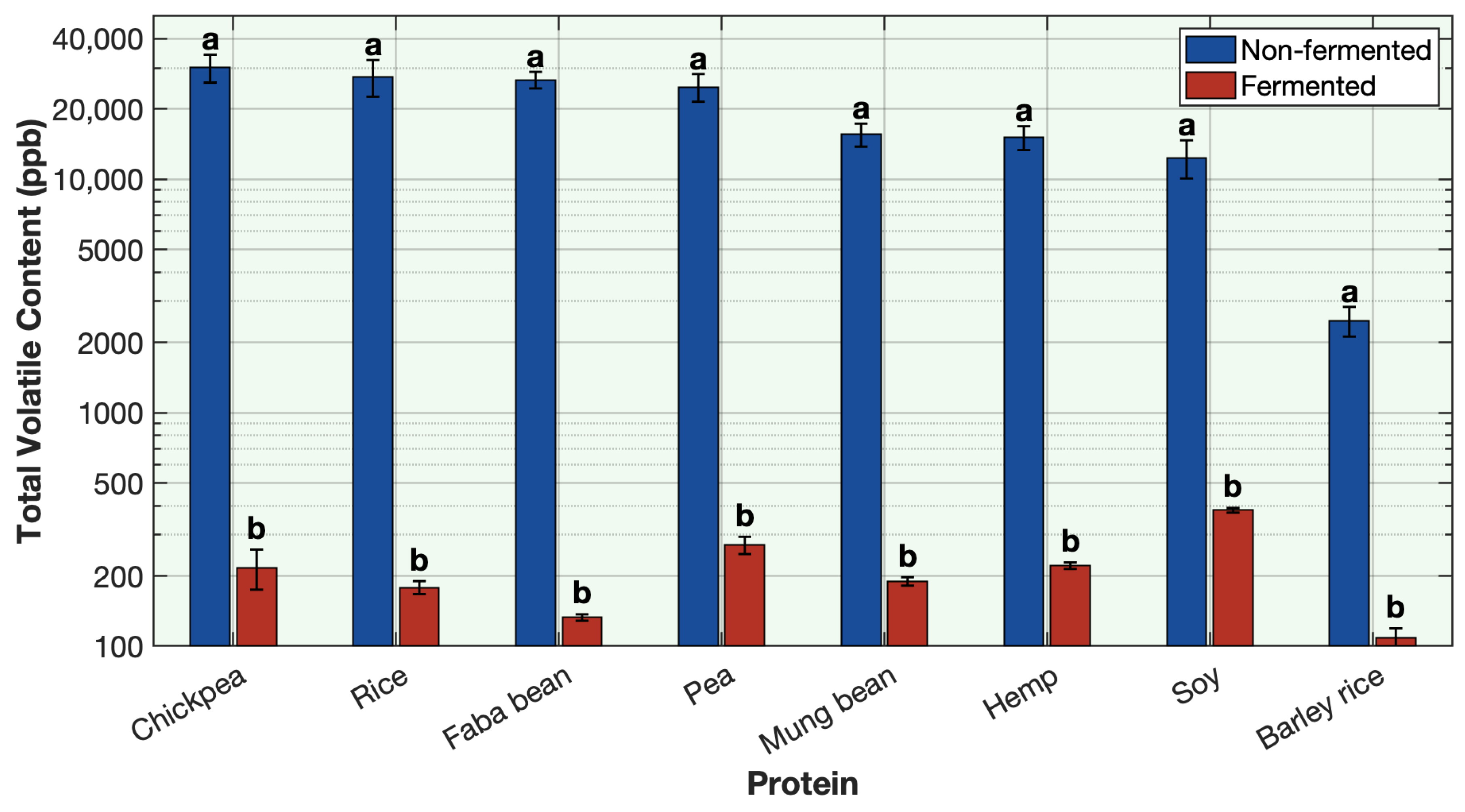

To evaluate the effectiveness of this method, key volatile compounds representing alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, sulfur volatiles, amines, pyrazines, and furans were quantified in yogurt alternatives produced from soy, pea, fava bean, chickpea, mung bean, hemp, rice, and barley-rice protein bases through sequential fermentation. The findings aim to demonstrate that sequential fermentation can serve as an effective strategy for deodorizing plant protein off-odors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Hydration of Plant Protein Solution

Plant proteins including pea (ProdEIM PEA 7028, Kerry Group, Sevilla, Spain) and rice (ProdEIM RICE 5020, Kerry Group, Sevilla, Spain), soy (ADM, Decatur, IL, USA), barley–rice (EverPro™, EverGrain Ingredients, St. Louis, MO, USA), mung bean (MB80C, Yantai T.Full Biotech Co., Ltd., Yantai, China), chickpea (CK80B, Yantai T.Full Biotech Co., Ltd., Yantai, China) and fava bean (FB90B, Yantai T.Full Biotech Co., Ltd., Yantai, China), and hemp protein (PurHP 75, Applied Food Sciences, Kerrville, TX, USA) were used in this study. To prepare the base mixture, plant protein powder was mixed with stabilizers (xanthan gum (Xan-80, AEP Colloids, Hadley, NY, USA) and/or low-methoxy pectin (GENU

® pectin type LM-101 AS, CPKelco, Lille Skensved, Denmark)) and allulose (It’s Just!™, Farmhouse Creative Foods, Fremont, CA, USA and Simple Truth™, The Kroger Co., Cincinnati, OH, USA) to ensure uniform distribution of all dry ingredients. This dry blend was gradually added to distilled water preheated to 55–60 °C, followed by high-shear blending using a high-speed blender (Ninja

® Professional 1100 W, SharkNinja Operating LLC, Needham, MA, USA) for 1 min to promote rapid dispersion and prevent clumping. During this blending step, 3% (

w/

v) extra virgin olive oil (Kroger™, The Kroger Co., Cincinnati, OH, USA) was also incorporated. The resulting mixture, containing 9% (

w/

v) plant protein and 10% (

w/

v) allulose, was then transferred to a beaker and maintained at 60 °C for 60 min on a magnetic hot plate stirrer (Guardian™ 5000, OHAUS Corporation, Parsippany, NJ, USA) set to 1100 rpm. Stabilizer concentrations were optimized by protein type, as shown in

Table 1:

Table 1.

Stabilizer composition by protein source.

Table 1.

Stabilizer composition by protein source.

| Proteins | Xanthan Gum % (w/v) | LM Pectin % (w/v) | Calcium Chloride% (w/v) |

|---|

| Soy, Pea, Fava Bean, Chickpea | 0.15 | - | - |

| Hemp, Rice protein, Barley rice, Mung bean | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.04 |

2.2. Pasteurization of the Plant Protein Solution

Following the 60-min hydration step, the protein solution was subjected to pasteurization to eliminate microbial contaminants and deactivate native enzymes that could interfere with fermentation. The solution was gradually heated to 72 °C over 20 min using the heating function of a magnetic hot plate stirrer (Guardian™ 5000, OHAUS Corporation, Parsippany, NJ, USA), while maintaining continuous stirring at 1100 rpm to ensure uniform temperature distribution and prevent localized overheating. Once the solution reached 72 °C, it was held at this temperature for 15 s to complete pasteurization. Immediately following pasteurization, the mixture was cooled to 50 °C, and for formulations containing low-methoxy pectin, 0.01% (w/v) calcium chloride (CaCl2·2H2O; ACS Certified, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA; Cat. No. C79-500) was added to initiate controlled gelation. Stirring was maintained during this step to ensure uniform calcium distribution and pectin activation without clumping.

2.2.1. Fermentation Stage 1—With Lactobacillus Plantarum

Following pasteurization, the mixture was cooled to 37 °C using a cold-water bath to initiate the first fermentation stage. Freeze-dried Lactobacillus plantarum (strain PRBT-022; Creative Enzymes, Shirley, NY, USA) was rehydrated in sterile lukewarm water and allowed to stand for 10 min with gentle stirring. A final concentration of 0.5% (w/v) was achieved upon addition to the protein solution.

2.2.2. Fermentation Setup and Incubation Conditions

The prepared plant protein solution was transferred into a sterile glass beaker for the first-stage fermentation. To minimize heat loss during incubation, the outer surface of the beaker was wrapped with aluminum foil layered with absorbent tissue paper, functioning as thermal insulation. The beaker was sealed with a layer of parafilm, and a sterile needle was inserted through the film and left in place to allow the controlled release of volatile compounds generated during fermentation. A thermometer probe was also inserted through the film to enable continuous monitoring and control of the internal temperature, which was maintained at 37 ± 1 °C. A PTFE-coated oval magnetic stir bar was used to gently agitate the viscous mixture at 500 rpm. This level of mixing ensured uniform acidification and homogeneity without introducing excess aeration, thus providing optimal conditions for the growth and metabolic activity of Lactobacillus plantarum. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 12 h under continuous stirring to ensure uniform exposure of the microbial cells to the substrate and promote effective deodorization.

2.3. Blending with Strawberry Preserve

Upon completion of the stage 1 fermentation step with Lactobacillus plantarum, 10% (w/v) strawberry preserve (Kroger™, The Kroger Co., Cincinnati, OH, USA) was added to approximately 20% of the stage 1 fermented mixture. This portion was blended in four cycles of 30 s blending followed by 30 s resting to ensure thorough dispersion of the preserve while minimizing heat generation. The blending was intentionally limited to a small portion of the mixture to reduce the risk of temperature-induced damage to the bacterial culture. Even if localized heating occurred during blending, only the blended 20% would be affected, while the remaining 80% of the stage 1 fermented mixture would retain a viable population of L. plantarum.

2.3.1. Fermentation Stage 2—With Yogurt Cultures—Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, and Lactobacillus acidophilus

Following recombination of the blended and unblended fractions, the second fermentation stage was initiated by adding a rehydrated commercial freeze-dried yogurt starter culture (Yogourmet®, Product of France; imported by C.A.P.Y.B.A.R.A Distributors Inc., Calgary, AB, Canada) containing Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, and Lactobacillus acidophilus. The freeze-dried culture was rehydrated in sterile lukewarm distilled water and rested for 10 min with gentle agitation before being added at a final concentration of 0.83% (w/v).

2.3.2. Incubation of Second Fermentation

The pre-fermented protein-strawberry preserve mixture was transferred into the container and sealed with its original tight-fitting lid, which helped maintain a controlled environment during incubation. The samples were incubated under static conditions at 37 ± 1 °C for 8 h (Soy, Pea, Fava Bean, Chickpea proteins) or 12 h (Hemp, Rice protein, Barley rice, Mung bean proteins) using a temperature-controlled yogurt maker (ULTIMATE™, Wilton, CT, USA), to support optimal texture development and controlled flavor formation.

2.4. Post-Fermentation Cooling

Following fermentation, the samples were first cooled at room temperature (approximately 25 °C) for 15 min to gradually transition from incubation temperature. This was followed by freezing at −18 °C for 30 min to halt microbial activity. The samples were then transferred to refrigeration at 4 °C and held for ~12 h to allow complete stabilization of the gel matrix.

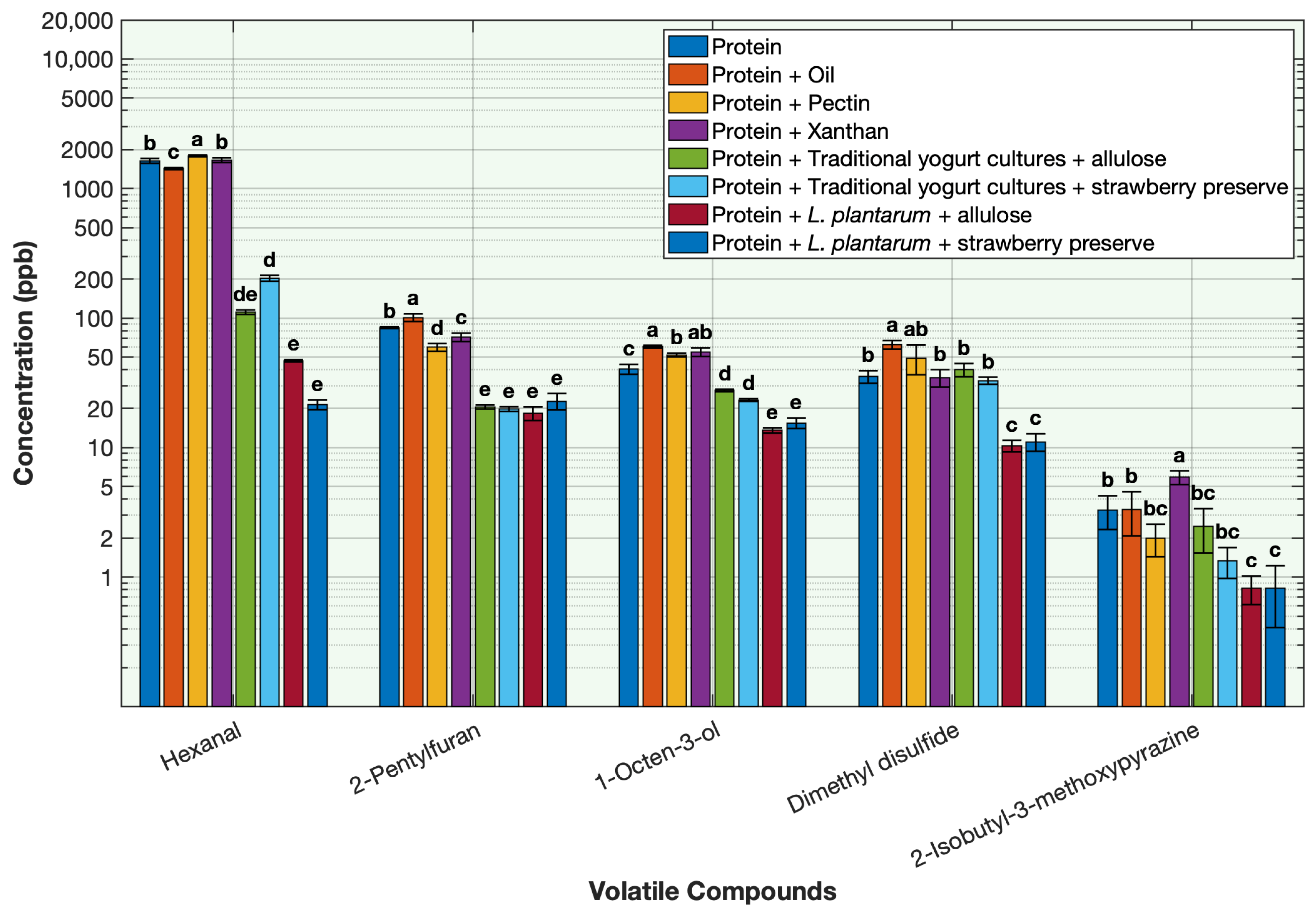

2.5. Effect of the Ingredients on the Deodorization of Off-Odor Producing Volatiles in Pea Protein

To evaluate the contribution of each ingredient used in the formulation of the protein solution on deodorization, volatile concentrations were measured in the base protein solution and compared across treatments containing each ingredient individually. The ingredients included L. plantarum with allulose, L. plantarum with strawberry preserve, traditional yogurt cultures with allulose, traditional yogurt cultures with strawberry preserve, oil, xanthan gum, and pectin. Each treatment was prepared using the same sample quantities as those used in the sequential fermentation formulation and processed under similar conditions to ensure comparability.

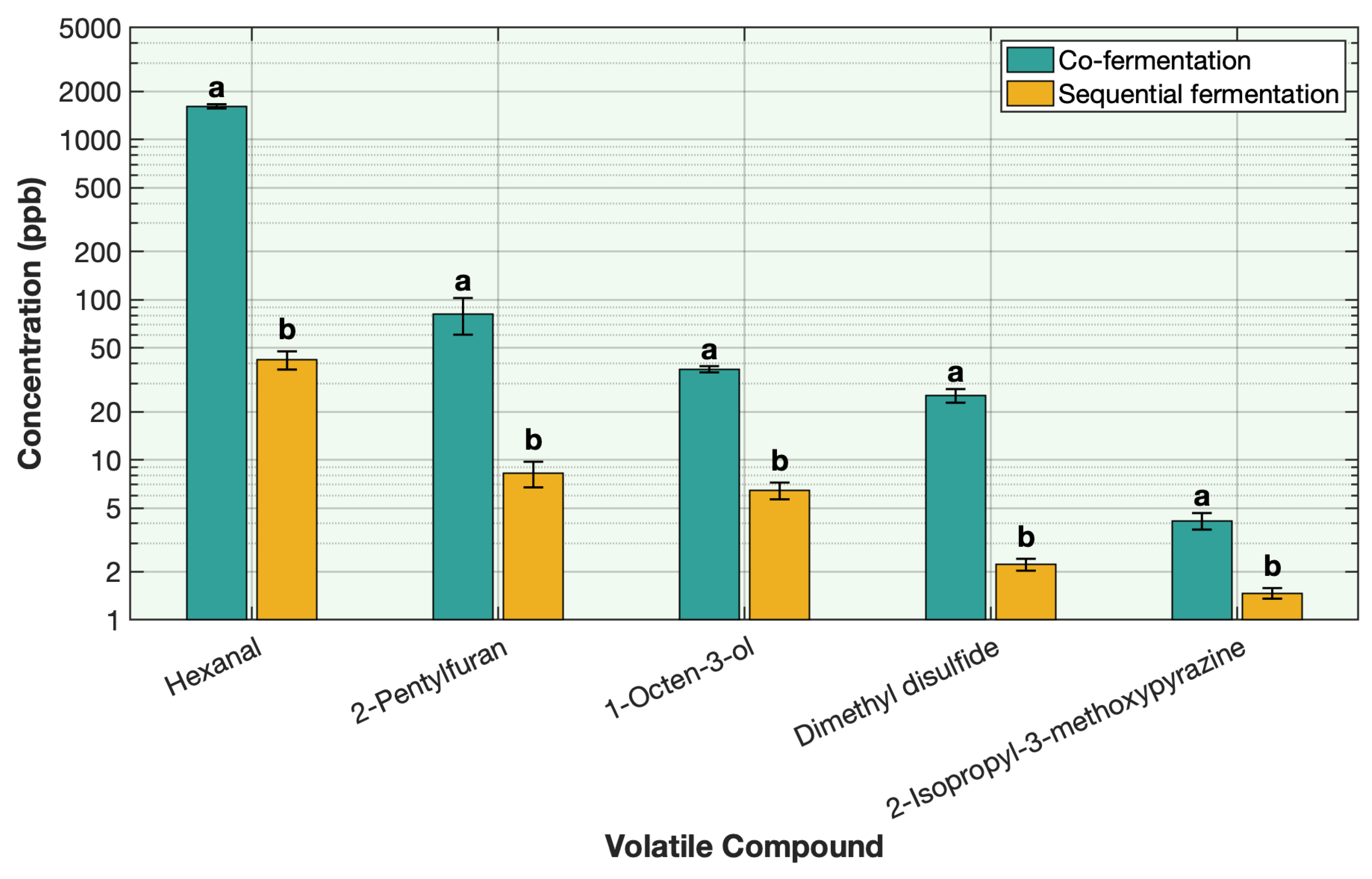

2.6. Effect of Co-Fermentation Versus Sequential Fermentation on the Deodorization of Off-Odor Producing Volatiles in Different Plant Proteins

All steps for sample preparation were the same as described previously for the protein solution, including hydration, heating, and ingredient incorporation. Pea protein was used as the representative protein for this comparison. The only variation between treatments was the fermentation approach. For the sequential fermentation, the sample was first fermented with

L. plantarum for 12 h, followed by the addition of strawberry preserve and inoculation with traditional yogurt cultures (

Streptococcus thermophilus and

Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp.

bulgaricus) for 8 h under similar conditions as explained in

Section 2.1. For the co-fermentation, all ingredients were added to the pea protein solution simultaneously, followed by inoculation with

L. plantarum and the traditional yogurt cultures at the same time. The mixture was then fermented for 20 h under similar conditions.

2.7. SIFT-MS Headspace Analysis

A 100 mL sample from each protein solution or its fermented yogurt was placed in a 500 mL Pyrex bottle. The bottle was sealed using an open-top septum-lined cap. Samples were equilibrated at room temperature for 30 min to allow headspace volatiles to stabilize. Volatile compounds (

Table 2) were analyzed using Selected Ion Flow Tube–Mass Spectrometry (SIFT-MS) (Voice200ultra, Syft Technologies, Christchurch, New Zealand). Analyses were conducted in Selected Ion Mode (SIM), employing precursor ions H

3O

+, NO

+, and O

2+. Quantification of volatile compounds was performed using known reaction rate coefficients for ion–molecule reactions. Calibration of the instrument was conducted using a certified gas standard containing benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, and xylene isomers. The instrument’s response was validated against known concentrations to ensure accuracy prior to sample analysis. During the test, a 14-gauge passivated needle was used to pierce the septum for sampling, with the inlet temperature maintained at 175 °C. Each sample was analyzed over a 120-s run. Three replicates were analyzed per sample type. Background levels were determined using an empty Pyrex bottle as a blank.

2.8. Sensory Evaluation

Based on Gacula and Rutenbeck (2006) [

12], 42 untrained consumer panelists were recruited for the sensory study. The panelists consisted of students at The Ohio State University. Participants were screened to ensure they did not have allergies to plant proteins and were free from known gustatory, severe vision, or olfactory deficits and had refrained from smoking for at least two hours prior to the start of the experiment.

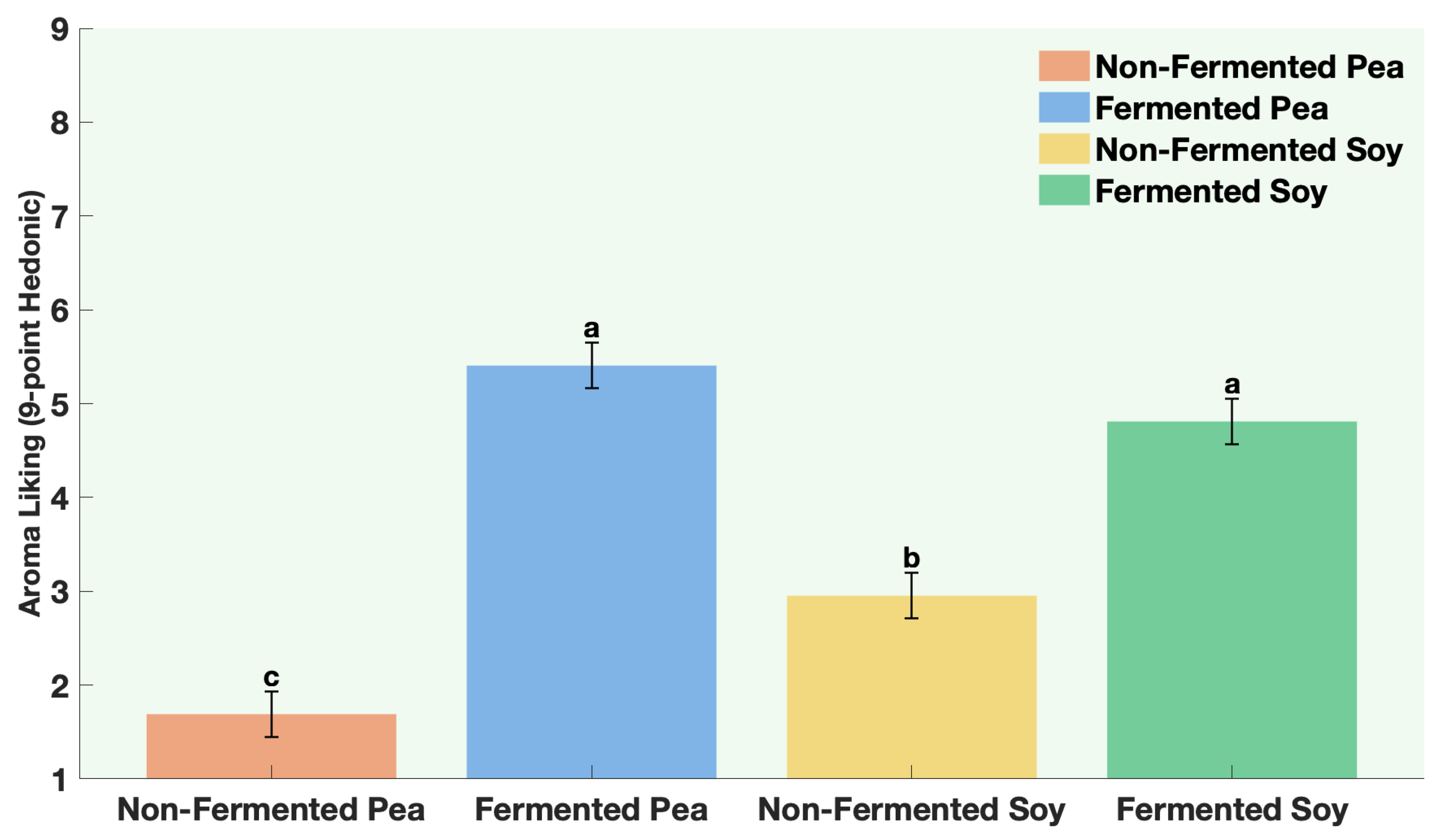

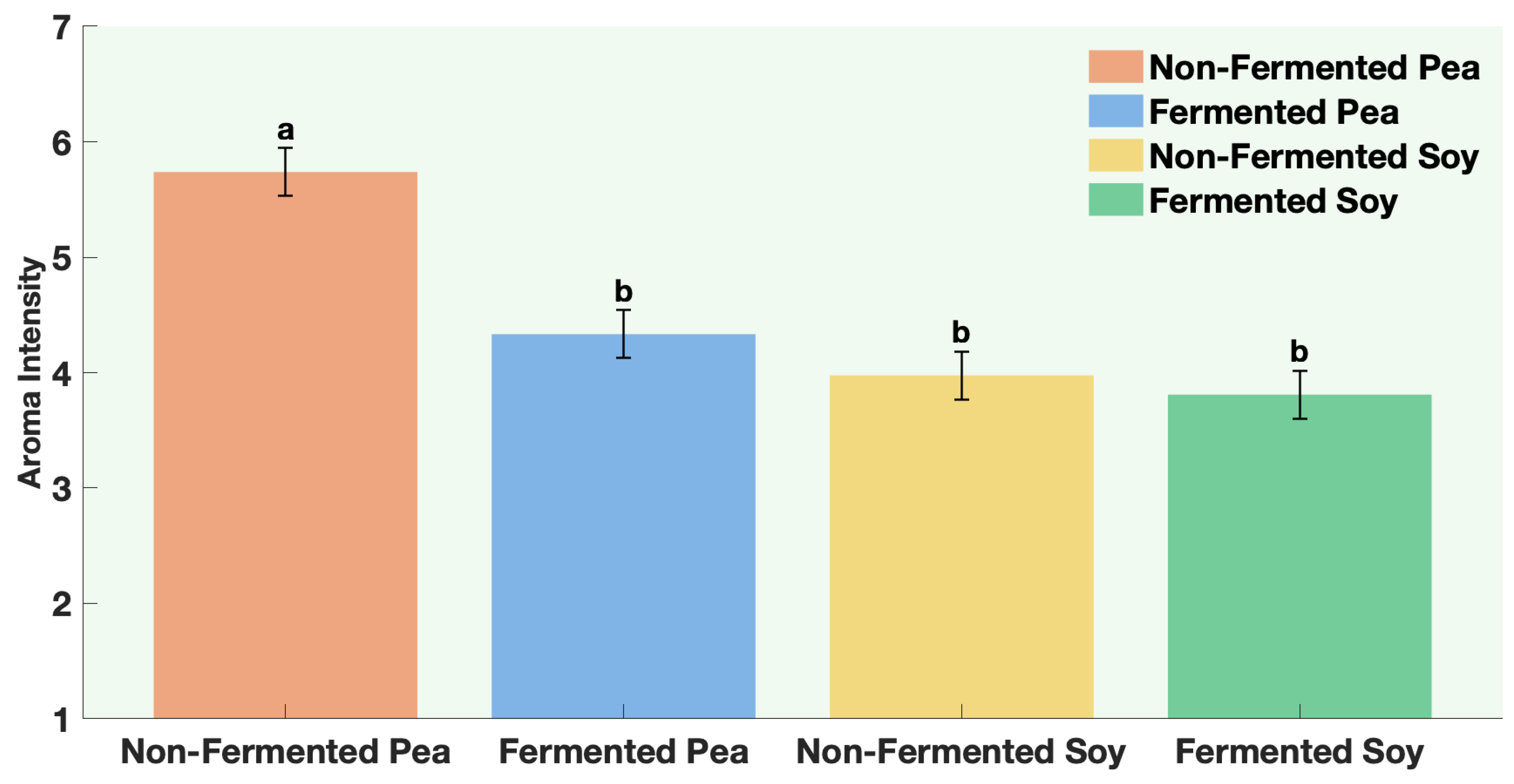

Samples consisted of 20 g of fermented or non-fermented protein samples and were evaluated at room temperature. Samples were presented in 100 mL Pyrex bottles with a lid and wrapped in aluminum foil to prevent the color of the sample from affecting the panelist’s feedback. The sample was labeled with random three-digit blinding codes and served in a fully randomized order to each participant. The experiments were conducted with a within-subjects design wherein each panelist served as his/her own control.

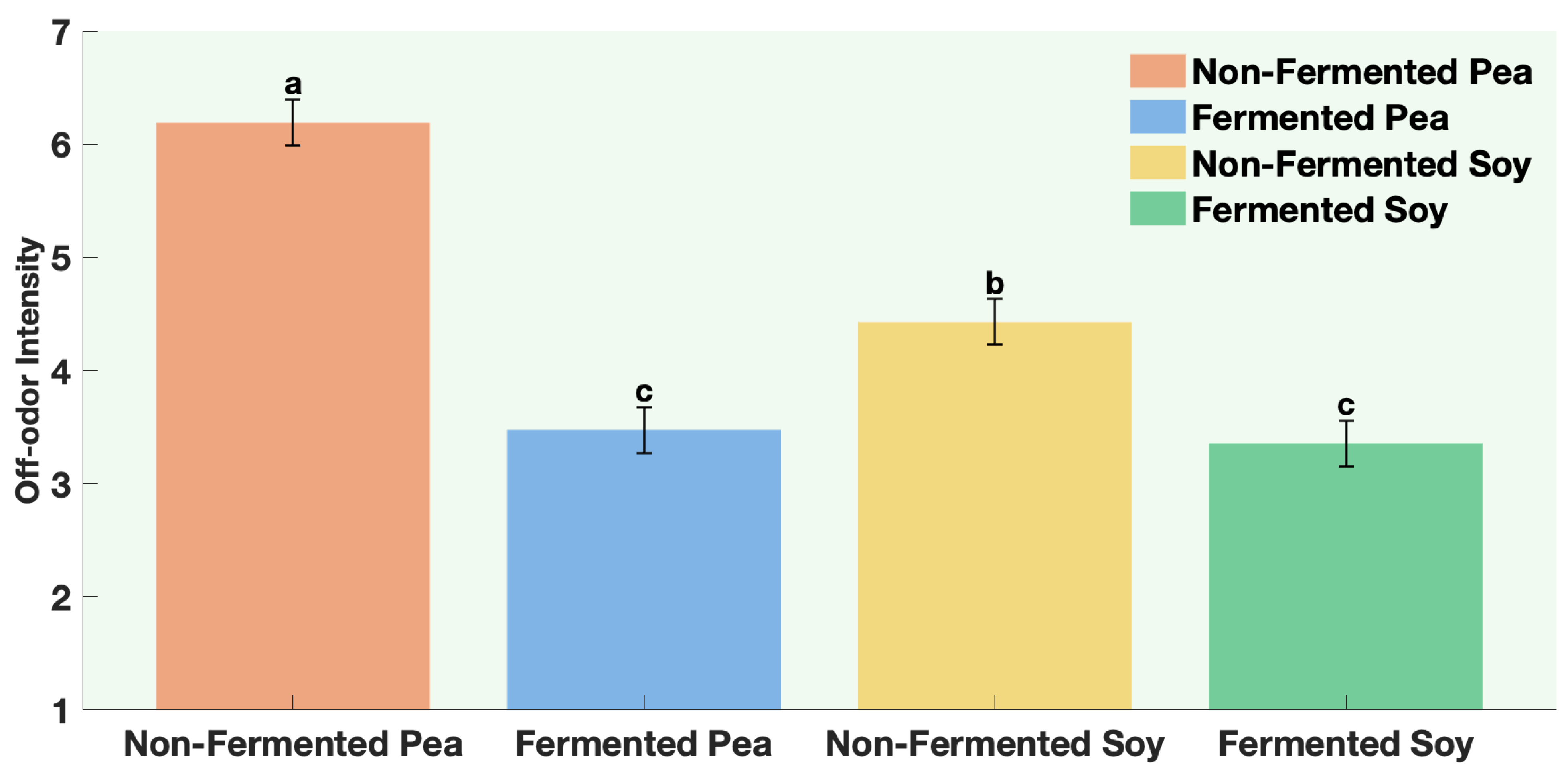

The samples were non-fermented pea protein, non-fermented soy protein, fermented pea protein, and fermented soy protein. Panelists were instructed to evaluate aroma only (no tasting) and to pause briefly between samples to minimize sensory fatigue. Participants evaluated four aroma attributes. Aroma liking was assessed on a 9-point hedonic scale from 1 = Dislike extremely to 9 = Like extremely. Aroma intensity and off-odor intensity were assessed on a 7-point descriptive scale from 1 = not perceptible to 7 = extremely strong. Panelists were also asked to rank the samples according to aroma preference from 1 = most preferred to 4 = least preferred.

All participants gave written informed consent prior to participation. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board (Study Number 20251170).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP® Pro Version 16.0.0 (Statistical Discovery, Cary, NC, USA). Graphical representations were generated using MATLAB® R2024b Update 5 (Version 24.2.0.2863752, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). A one-way ANOVA was performed for each protein to compare volatile concentrations between fermented and non-fermented samples, as well as to evaluate the effects of individual ingredients and co-fermentation versus sequential fermentation treatments. Post hoc comparisons were performed using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test, with statistical significance established at p ≤ 0.05. All analyses were based on triplicate samples (n = 3) for each tested factor. For sensory data, way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test, with statistical significance established at p ≤ 0.0001.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the remarkable effectiveness of sequential fermentation as a strategy for deodorizing plant-based proteins. By employing a two-stage sequential fermentation process initially with Lactobacillus plantarum followed by a traditional yogurt culture, the formulation achieved a broad and substantial reduction in off-odor volatile compounds across eight different plant proteins, including soy, pea, chickpea, mung bean, faba bean, rice, barley-rice, and hemp. The SIFT-MS headspace analysis and sensory results revealed consistent and often near-complete reductions in key off-odor volatiles such as aldehydes, alcohols, methoxypyrazines, ketones, and sulfur volatiles. Among the volatile classes, aldehydes, alcohols, and sulfur compounds showed the most dramatic decreases. This outcome is attributed to the synergistic enzymatic activities of the microbial cultures, supported by matrix acidification, redox effects, protein denaturation, and strategic venting during fermentation. The use of LAB cultures with specific sugar sources, such as allulose with L. plantarum and strawberry preserve with yogurt cultures, further enhanced the deodorization efficiency and contributed desirable sensory qualities to the final product. The co-fermentation approach, where all ingredients and cultures were combined simultaneously, was less effective. Although some deodorization was observed, it was not as effective as sequential fermentation. The simultaneous presence of multiple microbial strains likely led to early competition for nutrients and suboptimal enzymatic activity, highlighting the importance of sequential fermentation. This work not only advances the understanding of how fermentation can mitigate the sensory challenges associated with plant protein ingredients but also offers a practical, clean-label solution for the development of flavorful plant-based dairy alternatives. By combining microbiological expertise with food chemistry, the proposed method achieves deodorization without reliance on artificial additives. The successful application across diverse protein types reinforces the potential of this approach to be generalized in future plant-based product innovations.