Nanoemulsion Encapsulation of Fat-Soluble Vitamins: Advances in Technology, Bioaccessibility and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Conventional Emulsion | Nanoemulsion | |

|---|---|---|

| Droplet diameter | >500 nm | 10–500 nm |

| Thermodynamic stability | unstable | approaching thermodynamic stability |

| Kinetic stability | unstable | stability |

| Appearance | turbid to opaque | transparent or translucent or milky liquid |

| shape | spherical | spherical |

| polydispersity | often high (>40%) | typically low (<10–20%) |

| rheological properties | pseudoplastic/plastic flow | general Newtonian flow |

| emulsifiers | surfactants | surfactants plus co-surfactants |

2. Fat-Soluble Vitamins

2.1. Vitamin A

2.2. Vitamin D

2.3. Vitamin E

2.4. Vitamin K

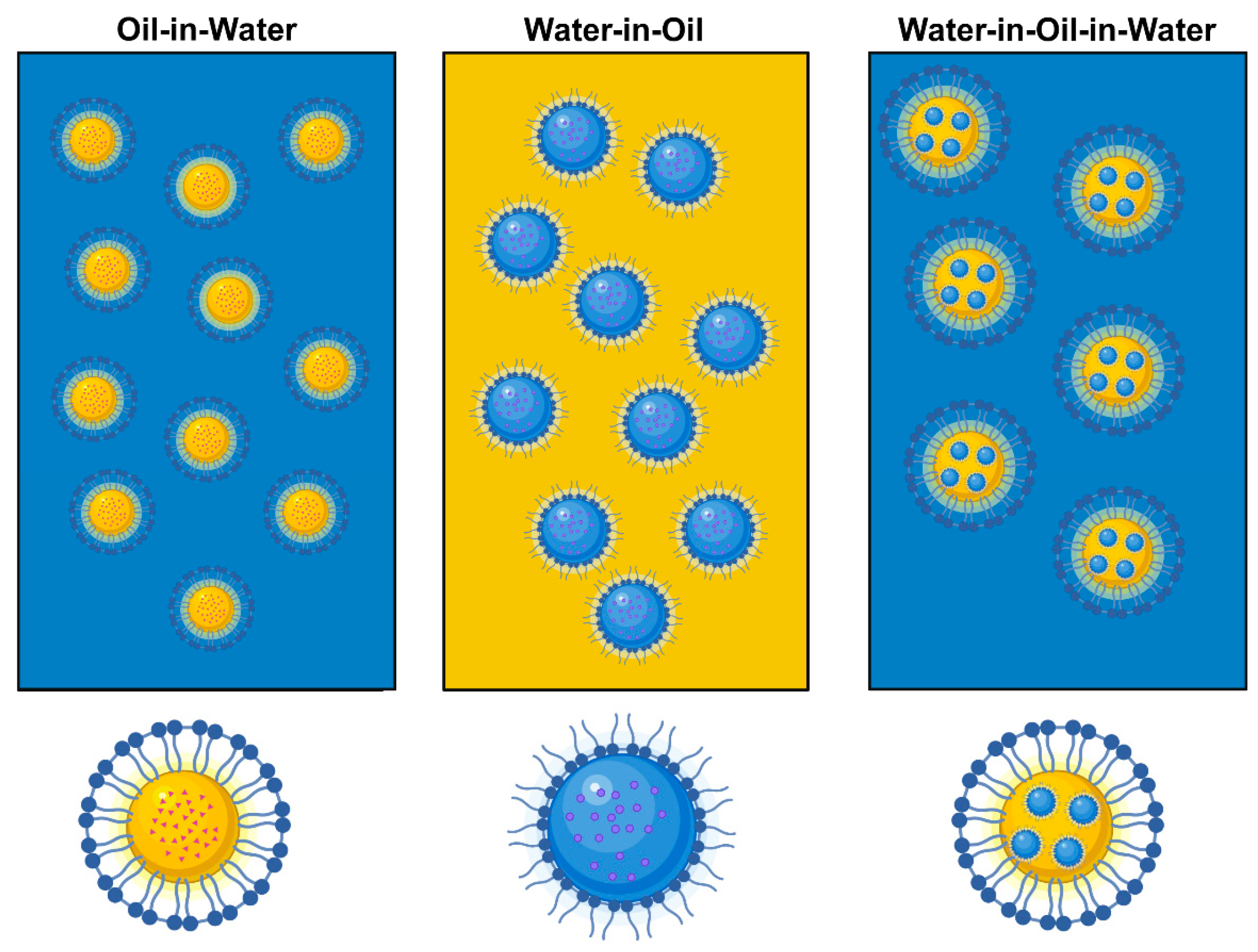

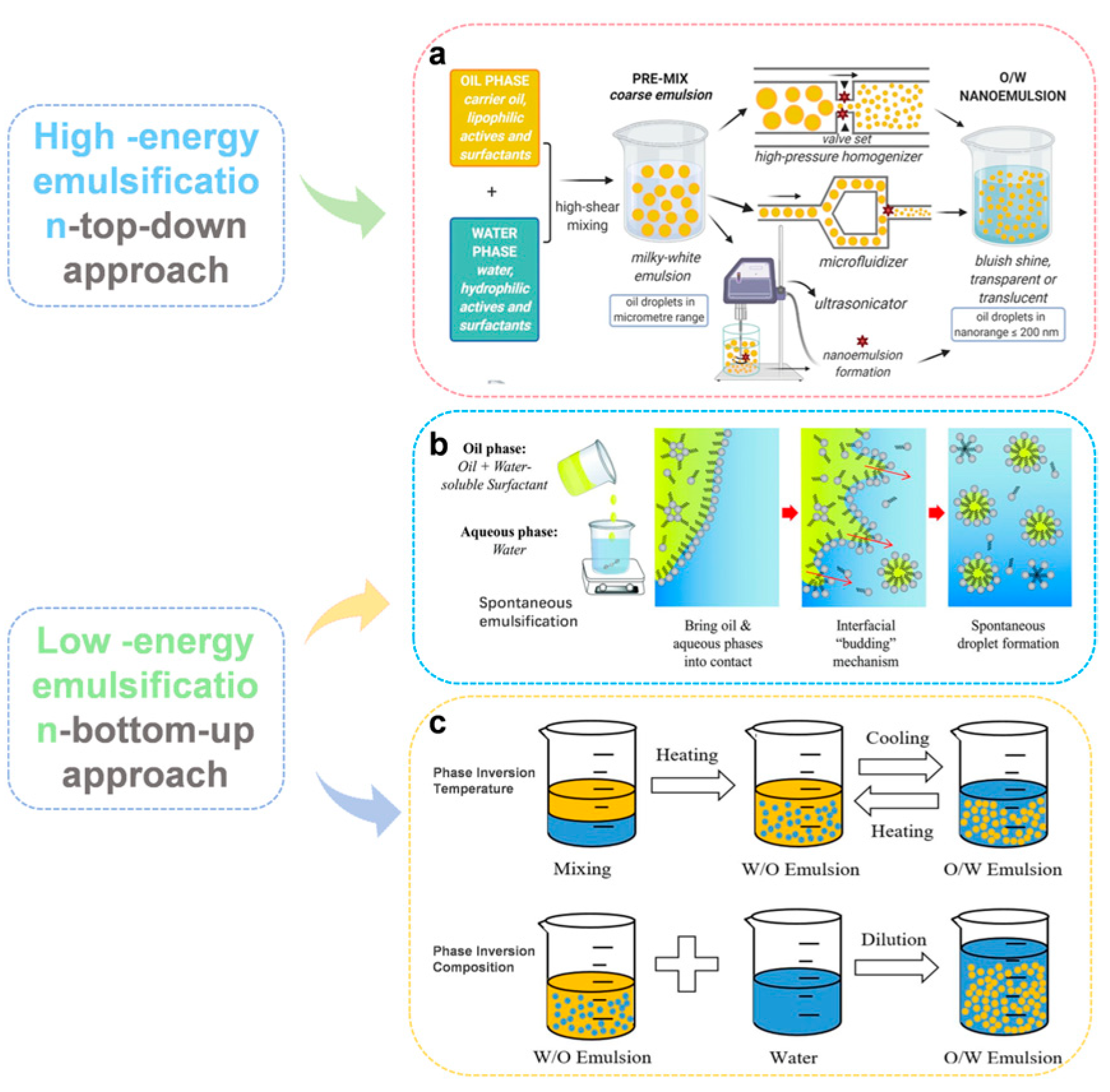

3. Preparation of Nanoemulsions

3.1. High-Energy Methods

3.1.1. High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH)

3.1.2. Ultrasonic Homogenization (USH)

3.1.3. Microfluidic Homogenization (MFH)

3.2. Low-Energy Methods

3.2.1. Spontaneous Emulsification (SE)

3.2.2. Phase Inversion Temperature (PIT)

3.2.3. Phase Inversion Composition (PIC)

4. Impact of Nanoemulsion Encapsulation on FSVs

4.1. Factors Affecting the Stability of FSVs Encapsulated in Nanoemulsions

4.2. Effect on Bioavailability of FSVs Encapsulated in Nanoemulsions

4.2.1. Carrier Oil Type

4.2.2. Oil Phase Composition and Concentration

4.2.3. Emulsifier Type

4.2.4. Droplet Size

5. Safety

6. Applications in the Food Industry

6.1. Nutritional Fortification

6.2. Dairy Product Fortification

6.3. Functional Beverage Fortification

6.4. Edible Packaging Materials

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amimo, J.O.; Michael, H.; Chepngeno, J.; Raev, S.A.; Saif, L.J.; Vlasova, A.N. Immune Impairment Associated with Vitamin A Deficiency: Insights from Clinical Studies and Animal Model Research. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennour, I.; Haroun, N.; Sicard, F.; Mounien, L.; Landrier, J.-F. Recent insights into vitamin D, adipocyte, and adipose tissue biology. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Sui, X. Dietary bioactive lipids: A review on absorption, metabolism, and health properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 8929–8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrštná, K.; Turoňová, D.; Suwanvecho, C.; Švec, F.; Krčmová, L.K. The power of modern extraction techniques: A breakthrough in vitamin K extraction from human serum. Microchem. J. 2024, 198, 110170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, M.M.J.O.; Mahmood, K.; Ariffin, F.; Nafchi, A.M.; Zulkurnain, M. Recent advances in encapsulation of fat-soluble vitamins using polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids: A review on delivery systems, formulation, and industrial applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Feng, T.; Wang, X.; Xia, S.; John Swing, C. Liposomes for encapsulation of liposoluble vitamins (A, D, E and K): Comparation of loading ability, storage stability and bilayer dynamics. Food Res. Int. 2023, 163, 112264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamisaye, A.; Adegoke, K.A.; Alli, Y.A.; Bamidele, M.O.; Idowu, M.A.; Ogunjinmi, O.E. Recent advances in nanoemulsion for sustainable development of farm-to-fork systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Rao, J. Food-grade nanoemulsions: Formulation, fabrication, properties, performance, biological fate, and potential toxicity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 285–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Martín-Belloso, O.; McClements, D.J. Excipient nanoemulsions for improving oral bioavailability of bioactives. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixé-Roig, J.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Martín-Belloso, O. Enhancing in vivo retinol bioavailability by incorporating β-carotene from alga Dunaliella salina into nanoemulsions containing natural-based emulsifiers. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, N.; Chen, L. Pea protein based vitamin D nanoemulsions: Fabrication, stability and in vitro study using Caco-2 cells. Food Chem. 2020, 305, 125475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, L.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, G.; Decker, E.A.; McClements, D.J. Enhancing Nutraceutical Bioavailability from Raw and Cooked Vegetables Using Excipient Emulsions: Influence of Lipid Type on Carotenoid Bioaccessibility from Carrots. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 10508–10517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; McClements, D.J.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Liu, X. Improvement of carotenoid bioaccessibility from spinach by co-ingesting with excipient nanoemulsions: Impact of the oil phase composition. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 5302–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Xiao, J.; Liu, X.; McClements, D.J.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, H. The gastrointestinal behavior of emulsifiers used to formulate excipient emulsions impact the bioavailability of β-carotene from spinach. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; McClements, D.J. Improving the bioavailability of oil-soluble vitamins by optimizing food matrix effects: A review. Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, C.; Mundo, J.M.; Zhou, H.; Liu, J.; McClements, D.J. Chitosan reduces vitamin D bioaccessibility in food emulsions by binding to mixed micelles. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biehler, E.; Kaulmann, A.; Hoffmann, L.; Krause, E.; Bohn, T. Dietary and host-related factors influencing carotenoid bioaccessibility from spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Food Chem. 2011, 125, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donsì, F.; Velikov, K.P. Encapsulation of food ingredients by single O/W and W/O nanoemulsions. In Encapsulation of Food Ingredients by Single O/W and W/O Nanoemulsions; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 37–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Eral, H.B.; Hatton, T.A.; Doyle, P.S. Nanoemulsions: Formation, properties and applications. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 2826–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carazo, A.; Macáková, K.; Matoušová, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Protti, M.; Mladěnka, P. Vitamin A Update: Forms, Sources, Kinetics, Detection, Function, Deficiency, Therapeutic Use and Toxicity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wayenbergh, E.; Verkempinck, S.H.E.; Courtin, C.M.; Grauwet, T. The impact of wheat bran on vitamin A bioaccessibility in lipid-containing systems. Food Chem. 2025, 490, 145082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvant, P.; Cansell, M.; Sassi, A.H.; Atgié, C. Vitamin A enrichment: Caution with encapsulation strategies used for food applications. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlotti, M.E.; Sapino, S.; Trotta, M.; Battaglia, L.; Vione, D.; Pelizzetti, E. Photostability and Stability over Time of Retinyl Palmitate in an O/W Emulsion and in SLN Introduced in the Emulsion. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2005, 26, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, V.K.; Shakya, A.; Bashir, K.; Kushwaha, S.C.; McClements, D.J. Vitamin A fortification: Recent advances in encapsulation technologies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 2772–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wayenbergh, E.; Struyf, N.; Rezaei, M.N.; Sagalowicz, L.; Bel-Rhlid, R.; Moccand, C.; Courtin, C.M. Cereal bran protects vitamin A from degradation during simmering and storage. Food Chem. 2020, 331, 127292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomhoff, R.; Blomhoff, H.K. Overview of retinoid metabolism and function. J. Neurobiol. 2006, 66, 606–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. Microencapsulation of vitamin A: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Zhang, F.; Lv, W.; Chen, W.; He, J.; Alouk, I.; Hou, Z.; Ren, S.; Gong, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. Fabrication of emulsion microparticles to improve the physicochemical stability of vitamin A acetate. Food Chem. 2025, 469, 142620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Hasan, M.R.; Furquani, J.M.J.; Begum, R. Stability of vitamin A in fortified soybean oil during prolonged storage and heating. Food Humanit. 2025, 4, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, N.; Dong, T.; Xing, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, W.; et al. Systematic metabolic engineering enables highly efficient production of vitamin A in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2025, 10, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.R.; Xu, W.; Mráz, J. Fabrication, stability and rheological properties of zein/chitosan particles stabilized Pickering emulsions with antioxidant activities of the encapsulated vit-D3. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, S.J.; Calvo, M.S. Vitamin D: Nutrition Information Brief. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2037–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, M.A.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Gonçalves, C.; Amado, I.R.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pastrana, L. Encapsulation of vitamin D3 using rhamnolipids-based nanostructured lipid carriers. Food Chem. 2023, 427, 136654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemery, Y.M.; Fontan, L.; Moench-Pfanner, R.; Laillou, A.; Berger, J.; Renaud, C.; Avallone, S. Influence of light exposure and oxidative status on the stability of vitamins A and D3 during the storage of fortified soybean oil. Food Chem. 2015, 184, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behjati, J.; Yazdanpanah, S. Nanoemulsion and emulsion vitamin D3 fortified edible film based on quince seed gum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 262, 117948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, K.; Jopek, Z.; Święcicka-Füchsel, E.; Kutyła, A.; Namo Ombugadu, J.; Wojciechowski, K. A new RPLC-ESI-MS method for the determination of eight vitamers of vitamin E. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, T.; Munné-Bosch, S. Vitamin E, total antioxidant capacity and potassium in tomatoes: A triangle of quality traits on the rise. Food Chem. 2025, 475, 143375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Nocella, C.; Loffredo, L.; Carnevale, R.; Pignatelli, P. Interventional study with vitamin E in cardiovascular disease and meta-analysis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 178, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosso, L.M.; Anderson, C.; Dafre, A.L.; Rodrigues, A.L.S. Vitamin E for the management of major depressive disorder: Possible role of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant systems. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 1310–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. The progress and application of vitamin E encapsulation—A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 121, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, T.; El Aoud, A.; Alvarado-Ramos, K.; Halimi, C.; Vairo, D.; Georgé, S.; Reboul, E. Impact of pulses, starches and meat on vitamin D and K postprandial responses in mice. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 133922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.; Kim, T.-E.; Jang, H.W.; Chun, Y.G.; Kim, B.-K. Physical and turbidimetric properties of cholecalciferol- and menaquinone-loaded lipid nanocarriers emulsified with polysorbate 80 and soy lecithin. Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallenahalli, S.; Rogers, B.D. Intracranial hemorrhage due to late-onset vitamin K deficiency bleeding. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2025, 95, 287.e285–287.e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, I.; Wani, S.M.; Jan, N.; Ali, A.; Rouf, A.; Sidiq, H.; Masood, S.; Mustafa, S. Optimizing ultrasonic parameters for development of vitamin D3-loaded gum arabic nanoemulsions—An approach for vitamin D3 fortification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, O.; Spotti, M.J. Nutraceutical delivery through nano-emulsions: General aspects, recent applications and patented inventions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 200, 111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Liao, W.; Charcosset, C. Recent advances in encapsulation of curcumin in nanoemulsions: A review of encapsulation technologies, bioaccessibility and applications. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, M.; Chen, X.G.; Kweon, D.K.; Park, H.J. Investigations on skin permeation of hyaluronic acid based nanoemulsion as transdermal carrier. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsions as delivery systems for lipophilic nutraceuticals: Strategies for improving their formulation, stability, functionality and bioavailability. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, A.; Wani, S.M.; Malik, A.R.; Gull, A.; Ramniwas, S.; Nayik, G.A.; Ercisli, S.; Marc, R.A.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A. Recent insights into Nanoemulsions: Their preparation, properties and applications. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Qian, C.; Martín-Belloso, O.; McClements, D.J. Modulating β-carotene bioaccessibility by controlling oil composition and concentration in edible nanoemulsions. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; McClements, D.J. Vitamin E bioaccessibility: Influence of carrier oil type on digestion and release of emulsified α-tocopherol acetate. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascrizzi, G.I.; Fuenmayor, C.A.; Piazza, L. Ultrasound-assisted nanoemulgel preparation: A one-step approach for enhanced rheo-tribological properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 106, 104246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.M.; Decker, E.A.; McClements, D.J. Physical and oxidative stability of fish oil nanoemulsions produced by spontaneous emulsification: Effect of surfactant concentration and particle size. J. Food Eng. 2015, 164, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, I.; Gledović, A.; Tamburić, S.; Major, T.; Savić, S. Nanoemulsions as Carriers for Natural Antioxidants: Formulation Development and Optimisation, 1st ed.; Aboudzadeh, M.A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 149–195. [Google Scholar]

- Komaiko, J.; McClements, D.J. Low-energy formation of edible nanoemulsions by spontaneous emulsification: Factors influencing particle size. J. Food Eng. 2015, 146, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Sun, Q.; Xue, S.; Shi, J.; Scanlon, M.G.; Wang, D.; Sun, Q. Emulsion-based formulations for delivery of vitamin E: Fabrication, characterization, in vitro release, bioaccessibility and bioavailability. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 3283–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoener, A.L.; Zhang, R.; Lv, S.; Weiss, J.; McClements, D.J. Fabrication of plant-based vitamin D3-fortified nanoemulsions: Influence of carrier oil type on vitamin bioaccessibility. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1826–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B.; Argin, S.; Ozilgen, M.; McClements, D.J. Formation and stabilization of nanoemulsion-based vitamin E delivery systems using natural surfactants: Quillaja saponin and lecithin. J. Food Eng. 2014, 142, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Ahmed, A. Tween 80 and Soya-Lecithin-Based Food-Grade Nanoemulsions for the Effective Delivery of Vitamin D. Langmuir 2020, 36, 2886–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, Y.; Al-Keridis, L.A.; Malik, M.; Haq, A.; Ahmad, S.; Kaur, J.; Adnan, M.; Alshammari, N.; Ashraf, S.A.; Panda, B.P. Preparation, modelling, characterization and release profile of vitamin D3 nanoemulsion. LWT 2022, 169, 113980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, L.; Liu, F.; Deng, Y.; McClements, D.J. Fabrication of β-carotene nanoemulsion-based delivery systems using dual-channel microfluidization: Physical and chemical stability. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 490, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Cuartas, C.; Granda-Restrepo, D.; Sobral, P.J.A.; Hernandez, H.; Castro, W. Characterization of whey protein-based films incorporated with natamycin and nanoemulsion of α-tocopherol. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, A.H.; Fang, Y.; McClements, D.J. Fabrication of vitamin E-enriched nanoemulsions: Factors affecting particle size using spontaneous emulsification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 391, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttoff, M.; Saberi, A.H.; McClements, D.J. Formation of vitamin D nanoemulsion-based delivery systems by spontaneous emulsification: Factors affecting particle size and stability. Food Chem. 2015, 171, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, N.; Zhang, S.; Wismer, W.; Chen, L. A low energy approach to develop nanoemulsion by combining pea protein and Tween 80 and its application for vitamin D delivery. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2022, 2, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, V.K.; Aggarwal, M. A phase inversion based nanoemulsion fabrication process to encapsulate vitamin D3 for food applications. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 190, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, N.; Ranjan, S.; Mundra, S.; Ramalingam, C.; Kumar, A. Fabrication of food grade vitamin E nanoemulsion by low energy approach, characterization and its application. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, M.S.; Sandhu, M.A. Optimization of mixed surfactants-based β-carotene nanoemulsions using response surface methodology: An ultrasonic homogenization approach. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, Z. Optimization of olive oil based O/W nanoemulsions prepared through ultrasonic homogenization: A response surface methodology approach. Food Chem. 2017, 229, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, N.H.C.; Wahab, R.A.; Hamid, M.A. An overview of nanoemulsion: Concepts of development and cosmeceutical applications. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2019, 33, 779–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, S.; Salem, M. Nanoemulsions in Food Industry, 1st ed.; Milani, J.M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S.; Yaoyao, M.; Hui, J.; Obadi, M.; Zhongwei, C.; Bin, X. Effects of single- and dual-frequency ultrasound on the functionality of egg white protein. J. Food Eng. 2020, 277, 109902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, M.S.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Ahmad, J. Investigation of Factors Influencing Formation of Nanoemulsion by Spontaneous Emulsification: Impact on Droplet Size, Polydispersity Index, and Stability. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, N.; Vandamme, T.F. The universality of low-energy nano-emulsification. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 377, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Nguyen, A.T.; Vu, H.Q.; Tran, N.N.; Sareela, M.; Fisk, I.; Hessel, V. Microfluidic Spontaneous Emulsification for Generation of O/W Nanoemulsions—Opportunity for In-Space Manufacturing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2203363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneha, K.; Kumar, A. Nanoemulsions: Techniques for the preparation and the recent advances in their food applications. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 76, 102914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushani, A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Food-Grade Nanoemulsions for Protection and Delivery of Nutrients, 1st ed.; Ranjan, N.D.S., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 99–139. [Google Scholar]

- Espitia, P.J.P.; Fuenmayor, C.A.; Otoni, C.G. Nanoemulsions: Synthesis, characterization, and application in bio-based active food packaging. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Rojas-Graü, M.A.; McClements, D.J.; Martín-Belloso, O. Edible nanoemulsions as carriers of active ingredients: A review. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 439–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, L.; Yang, J.; Xu, D.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Effects of Homogenization Models and Emulsifiers on the Physicochemical Properties of β-Carotene Nanoemulsions. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2010, 31, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shi, J.; Du, X.; McClements, D.J.; Chen, X.; Duan, M.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Shao, Y.; Cheng, Y. Polysaccharide conjugates from Chin brick tea (Camellia sinensis) improve the physicochemical stability and bioaccessibility of β-carotene in oil-in-water nanoemulsions. Food Chem. 2021, 357, 129714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasa-Falcon, A.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Martín-Belloso, O. Impact of emulsifier nature and concentration on the stability of β-carotene enriched nanoemulsions during in vitro digestion. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Decker, E.A.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsion delivery systems: Influence of carrier oil on β-carotene bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Han, Y.; Du, H.; McClements, D.J.; Tang, Z.; Xiao, H. Exploring the effects of carrier oil type on in vitro bioavailability of β-carotene: A cell culture study of carotenoid-enriched nanoemulsions. LWT 2020, 134, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; McClements, D.J.; Yan, C.; Xiao, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Hou, X.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Liu, X. In vitro and in vivo study of the enhancement of carotenoid bioavailability in vegetables using excipient nanoemulsions: Impact of lipid content. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Factors impacting lipid digestion and β-carotene bioaccessibility assessed by standardized gastrointestinal model (INFOGEST): Oil droplet concentration. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7126–7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Qian, C.; Martín-Belloso, O.; McClements, D.J. Influence of particle size on lipid digestion and β-carotene bioaccessibility in emulsions and nanoemulsions. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadappan, A.S.; Guo, C.; Gumus, C.E.; Bessey, A.; Wood, R.J.; McClements, D.J.; Liu, Z. The Efficacy of Nanoemulsion-Based Delivery to Improve Vitamin D Absorption: Comparison of In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Mundo, J.M.; McClements, D.J. Impact of an indigestible oil phase (mineral oil) on the bioaccessibility of vitamin D3 encapsulated in whey protein-stabilized nanoemulsions. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R.; Chang, M.; Wang, X. Medium and long-chain structured triacylglycerol enhances vitamin D bioavailability in an emulsion-based delivery system: Combination of in vitro and in vivo studies. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 1762–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Fumiaki, B.; Park, Y.; McClements, D.J. The influence of lipid droplet size on the oral bioavailability of vitamin D2 encapsulated in emulsions: An in vitro and in vivo study. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthasarathi, S.; Muthukumar, S.P.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. The influence of droplet size on the stability, in vivo digestion, and oral bioavailability of vitamin E emulsions. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2294–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Impact of lipid phase on the bioavailability of vitamin E in emulsion-based delivery systems: Relative importance of bioaccessibility, absorption, and transformation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3946–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhang, R.; McClements, D.J. Vitamin E encapsulation within oil-in-water emulsions: Impact of emulsifier type on physicochemical stability and bioaccessibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campani, V.; Biondi, M.; Mayol, L.; Cilurzo, F.; Pitaro, M.; De Rosa, G. Development of nanoemulsions for topical delivery of vitamin K1. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 511, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Mao, L. Characterization and stability evaluation of β-carotene nanoemulsions prepared by high pressure homogenization under various emulsifying conditions. Food Res. Int. 2008, 41, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Wang, D.; Liu, F.; Gao, Y. Emulsion design for the delivery of β-carotene in complex food systems. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Cao, C.; Liu, Y.; Cao, P.; Li, Q. Triglyceride structure modulates gastrointestinal digestion fates of lipids: A comparative study between typical edible oils and triglycerides using fully designed in vitro digestion model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6227–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Decker, E.A.; McClements, D.J. Influence of lipid type on gastrointestinal fate of oil-in-water emulsions: In vitro digestion study. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Decker, E.A.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Nutraceutical nanoemulsions: Influence of carrier oil composition (digestible versus indigestible oil) on β-carotene bioavailability. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3175–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Edible nanoemulsions: Fabrication, properties, and functional performance. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 2297–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Decker, E.A.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Physical and chemical stability of β-carotene-enriched nanoemulsions: Influence of pH, ionic strength, temperature, and emulsifier type. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, H.R.; Goff, H.D.; Majeed, H.; Liu, F.; Nsor-Atindana, J.; Haider, J.; Liang, R.; Zhong, F. Physicochemical stability of β-carotene and α-tocopherol enriched nanoemulsions: Influence of carrier oil, emulsifier and antioxidant. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 529, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Kumar, R.; Arpita; Goel, S.; Uppal, S.; Bhatia, A.; Mehta, S.K. Physiochemical and cytotoxicity study of TPGS stabilized nanoemulsion designed by ultrasonication method. Ultrason. Sonochem 2017, 34, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooster, T.J.; Moore, S.C.; Chen, W.; Andrews, H.; Addepalli, R.; Seymour, R.B.; Osborne, S.A. Biological fate of food nanoemulsions and the nutrients they carry—Internalisation, transport and cytotoxicity of edible nanoemulsions in Caco-2 intestinal cells. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 40053–40066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Escobar, M.P.; Pascual-Mathey, L.I.; Beristain, C.I.; Flores-Andrade, E.; Jiménez, M.; Pascual-Pineda, L.A. In vitro and In vivo antioxidant properties of paprika carotenoids nanoemulsions. LWT 2020, 118, 108694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Leser, M.E.; Sher, A.A.; McClements, D.J. Formation and stability of emulsions using a natural small molecule surfactant: Quillaja saponin (Q-Naturale®). Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 30, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, T.A.; Masoodi, F.A.; Jafari, S.M.; McClements, D.J. Chapter 19—Safety of Nanoemulsions and Their Regulatory Status, 1st ed.; Jafari, S.M., McClements, D.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 613–628. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, G.; Panigrahi, C.; Agarwal, S.; Khuntia, A.; Sahoo, M. Recent trends and advancements in nanoemulsions: Production methods, functional properties, applications in food sector, safety and toxicological effects. Food Phys. 2024, 1, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borel, T.; Sabliov, C.M. Nanodelivery of Bioactive Components for Food Applications: Types of Delivery Systems, Properties, and Their Effect on ADME Profiles and Toxicity of Nanoparticles. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockburn, A.; Bradford, R.; Buck, N.; Constable, A.; Edwards, G.; Haber, B.; Hepburn, P.; Howlett, J.; Kampers, F.; Klein, C.; et al. Approaches to the safety assessment of engineered nanomaterials (ENM) in food. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 2224–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriramavaratharajan, V.; Chellappan, D.R.; Karthi, S.; Ilamathi, M.; Murugan, R. Multi target interactions of essential oil nanoemulsion of Cinnamomum travancoricum against diabetes mellitus via in vitro, in vivo and in silico approaches. Process Biochem. 2022, 118, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.S.D.; Bazana, M.T.; Deus, C.D.; Machado, M.L.; Cordeiro, L.M.; Soares, F.A.A.; Libreloto, D.R.N.; Rolim, C.M.B.; Menezes, C.R.D.; Codevilla, C.F. Physicochemical characterization and evaluation of in vitro and in vivo toxicity of goldenberry extract nanoemulsion. Ciência Rural 2019, 49, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, Z.; Ahmad, M.S. Optimization of soya lecithin and Tween 80 based novel vitamin D nanoemulsions prepared by ultrasonication using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, C.M.; Tavares, M.N.; Macedo, L.P.; Araújo, G.S.; Furlong, E.B.; Dora, C.L.; Burkert, J.F.M. Physical and chemical stability of β-carotene nanoemulsions during storage and thermal process. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Butt, M.S.; Pasha, I.; Saeed, M.; Yasmin, I.; Ali, M.; Azam, M.; Khan, M.S. Bioavailability, rheology, and sensory evaluation of mayonnaise fortified with vitamin D encapsulated in protein-based carriers. J. Texture Stud. 2020, 51, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golfomitsou, I.; Mitsou, E.; Xenakis, A.; Papadimitriou, V. Development of food grade O/W nanoemulsions as carriers of vitamin D for the fortification of emulsion based food matrices: A structural and activity study. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 268, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; He, L.; McClements, D.J. Fortification of Plant-Based Milk with Calcium May Reduce Vitamin D Bioaccessibility: An In Vitro Digestion Study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 4223–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikos, V. Encapsulation of vitamin E in edible orange oil-in-water emulsion beverages: Influence of heating temperature on physicochemical stability during chilled storage. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 72, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkam, Y.; Rababah, T.; Costa, R.; Almajwal, A.; Feng, H.; Laborde, J.E.A.; Abulmeaty, M.M.; Razak, S. Pea Protein Nanoemulsion Effectively Stabilizes Vitamin D in Food Products: A Potential Supplementation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artiga-Artigas, M.; Acevedo-Fani, A.; Martín-Belloso, O. Effect of sodium alginate incorporation procedure on the physicochemical properties of nanoemulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 70, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, P.; Yazdanpanah, S.; Shahamirian, M.; Shirazinejad, A. Fabrication and analysis of nanoemulsion-based edible films loaded with vitamin D3 and Cordia myxa mucilage. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, M.; Li, L.; Jia, P.; Bu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Development of functional gelatin-based composite films incorporating oil-in-water lavender essential oil nano-emulsions: Effects on physicochemical properties and cherry tomatoes preservation. LWT 2021, 142, 110987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, R.; Zheng, T.; Tang, P.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, C.; Gu, M.; Li, G. Antioxidant and antimicrobial collagen films incorporating Pickering emulsions of cinnamon essential oil for pork preservation. Food Chem. 2023, 420, 136108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Surfactant(s) (w/w%) | Oil (w/w%) | Vitamin Concentration (w/w%) | Emulsification Process | DZ (nm)/PDI | ZP (mV) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSH | Lecithin (2 a) and Q-Naturale (0.5 a) | 10 a (VE:orange oil = 1:1) | 0.5 a | High-speed blending followed by high pressure homogenization (12,000 psi, 3 passes) | <200/- | −60 | [58] |

| Pea Protein (2 a) | 10 a (99 a flaxseed oil/corn oil/fish oil + 1 a vitamin D3) | 0.1 a | High-speed blending followed by high pressure homogenization (12,000 psi, 5 passes) | 200~550/- | - | [57] | |

| Pea Protein (1 a) and Soy Lecithin (1 a) | 0.5~5 a canola oil | 0.5 a | High-speed blending followed by high pressure homogenization (20 kpsi, 2 cycles) | <350/<0.3 | −25 | [11] | |

| USH | Tween 80 and soya lecithin (2.64–9.36%) | olive oil (10%) | 5.48–10.52% | Mixing with magnetic stirrer (8000 rpm, 7 min) followed by Sonication (20 kHz, 2.98–8.02 min) | 119.33 nm/- | - | [59] |

| KolliphorRH-40 (600 μL) + Ethylene Glycol (400 μL) | MCT Oil (100 μL) | - | Mixing with magnetic stirrer (1500 rpm, 10 min) followed by ultrasonication (50 kHz, 30 s) | 169/0.288 | −22.6 | [60] | |

| MFH | Quillaja Saponins (1 a) and Whey Protein Isolate (1 a) | 10 a corn oil | 0.1 a | Dual-channel microfluidizer (13 kpsi, 1 pass) | <150/- | −22.6 | [61] |

| Tween 80 (0.30 a) + Span 60 (0.19 a) | 1.29 a α-TOC | 1.29 a | Spontaneous emulsification followed by microfluidization (70 MPa, 3 cycles) | <200/- | - | [62] | |

| SE | TWEENÒ 80 (10 a) | 10 a (8 a VE + 2 a MCT oil) | 0.8 a | Magnetic stirring (500 rpm, 25 °C) | <200/<0.3 | - | [63] |

| Tween 80 (10 a) | 10 a MCT oil | 2.5 a | Magnetic stirring (500 rpm, 25 °C) | <200/<0.3 | - | [64] | |

| Tween 80 (3 b) + Pea Protein (3 b) | 3 b canola oil | 1 c | Magnetic stirring (800 rpm, 25 °C) | 207.7/0.31 | 3.7 | [65] | |

| PIT | Kolliphor®HS15 (10–40 b) + CCTG (10–25 b) | 10–30 b Leciva S70 | 0.2 b | Magnetic stirring (five temperature cycles, 85 °C–65 °C–85 °C–65 °C–85 °C–65 °C–85 °C–65 °C–85 °C–65 °C–85 °C) | <100/- | <20 | [66] |

| PIC | Tween 80 (5 a) | 3 a Mustard oil | 2 a | Magnetic stirring (400 rpm, 25 °C) | 86.45 ± 3.61/0.391 + 0.43 | - | [67] |

| Bioactive Compound | Fabrication Method | Surfactant(s) (w/w%) | Oil (w/w%) | Vitamin Dispersion Method and Concentration (w/w%) | Emulsification Process | DZ (nm)/PDI | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-carotene | MSH and HPH | OSA/Tween 20/WPI/TW, DML (10 a) | Medium chain triglyceride (MCT) oil (10 d) | β-carotene was dissolved in MCT (140 °C, several seconds)/1 d | High speed blender (5000 rpm), HPH (100 MPa, 3 passes)/MSH (100 MPa, 3 passes) | <300 nm/(0.12 < PDI < 0.26) | Small molecule emulsifiers produce smaller droplets in nanoemulsions than large molecule ones, but macromolecular emulsifiers have better stability for β-carotene. | [80] |

| β-carotene | HPH | TPC (2.0 d)/WPI (1.0 d)/Tween 80 (1.0 d) | Corn oil (8 d) | β-carotene was dissolved in corn oil (sonicating 10 min, 50 °C, 30 min)/0.1 a | High-speed shearer (25,000 rpm, 3 min), HPH (75 MPa, 3 passes) | <140 nm/- | The stability in TPC stabilized nanoemulsions significantly higher than Tween 80 and WPI. | [81] |

| β-carotene | USH | Tween 80 and soya lecithin (2.64–9.36 a) | Olive oil (10 a) | β-carotene was dissolved in olive oil (−)/5.48–10.52 a | Magnetic stirrer (8000 rpm, 7 min), USH (20 kHz, 2.98–8.02 min) | 119.33 nm/- | As the surfactant concentration rises, the rate of β-carotene degradation diminishes. | [68] |

| β-carotene | MSH | Tween 20/lecithin/sodium caseinate/sucrose palmitate (2–8%) | Corn oil (4 a) | β-carotene was dissolved in corn oil (−)/0.5 a | High-speed shearer (9500 rpm, 2 min), MSH (30,000 psi, 5 times) | -/- | The stability and particle size behavior of β-carotene nanoemulsions during in vitro digestion are significantly influenced by the type and concentration of emulsifiers used. | [82] |

| β-carotene | MSH | SBL (0.25 a/0.75 a)/WPI (0.25 a/0.75 a) | Corn oil (10 a/30 a) | β-carotene was mixed with corn oil (65 °C, 3000 rpm for 1 min; 17,500 for rpm 2 min, sonication bath for 5 min repeated twice; 9000 rpm for 15 min)/20 d | Homogenizer (11,000 rpm, 2 min), MSH (130 MPa, 5 passes) | <500 nm/- | WPI (Cmax685 ng/mL) enhances retinol bioavailability more than SBL (Cmax394 ng/mL) due to better gut absorption. | [10] |

| VD3 | HPH | Pea protein (1 b, 5 b and 10 b) | Canola oil (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 b) | Vitamin D3 was dissolved in canola oil/(11.7 e) | High-speed mixer (30,000 rpm, 2 min), HPH (10, 20 and 30 kpsi, 1–5 cycles) | 170–350 nm/(PDI < 0.3) | Pea protein nanoemulsions (P 230) exhibited approximately 5.3-fold higher transport efficiency across Caco-2 cells (Cancer coli-2) compared to free vitamin D suspension; The cellular uptake efficiency was also about 2.5 times higher than that of pea protein nanoemulsions (P 350) | [11] |

| β-carotene | MSH | Tween 20 (1.5 a) | Corn oil/MCT/orange oil (4 a) | Crystalline β-carotene was dissolved in oil phase (50 °C, <5 min, 1 h)/0.5 a | High-speed blender (2 min), MSH (9000 psi, 3 times) | 140–170 nm/- | The bioaccessibility was much higher for LCT (68%) nanoemulsions than for MCT (2%) nanoemulsions. | [83] |

| β-carotene | MSH | Tween 20 (0.5 a) | Olive or flaxseed oil (4 a) | β-carotene was dissolved in olive or flaxseed oil (−)/0.04 b | High-shear mixer (3 min), MSH (9000 psi, 3 times. | <200 nm/- | β-carotene bioaccessibility was greater for olive oil (65.2%) than for flaxseed oil (47.8%). | [84] |

| β-carotene | MSH | Tween 20 (1.5 a) | MCT or LCT (1 a/4 a) | β-carotene was dissolved in MCT or LCT (sonicating 1 min, 50 °C, 5 min)/0.5 a | High-shear mixer (10,000 rpm, 2 min), MSH (9000 psi, 3 times) | <500 nm/- | When the oil concentration was 4% (w/w), the bioaccessibility of the nanoemulsions first decreased and then increased with the increase in LCT content. When the oil concentration was 1% (w/w), the bioaccessibility increased from about 14% to 86% with the increase of LCT content. | [50] |

| β-carotene | HPH | Sodium caseinate (1 a) | MCT:LCT = 1:1 (10 a) | β-carotene was dissolved in oil phase (−)/0.6 a | High-shear blender (10,000 rpm, 2 min), HPH (12,000 psi, five times) | <180 nm/(PDI < 0.2) | The bioavailability increased with increasing lipid content. | [85] |

| β-carotene | MSH | Tween 20 (2 d) | Corn oil (20 d) | β-carotene was dissolved in corn oil (sonication 40 kHz, 1 min, 50 °C, 5 min)/0.1 d | High-shear blender (10,000 rpm, 2 min), MSH (12,000 psi, 3 passes) | <200 nm/- | The bioavailability of β-carotene shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with oil concentration | [86] |

| β-carotene | MSH | Tween 20 (1.5 a) | Corn oil (4 a) | β-carotene was dissolved in corn oil (sonicating 1 min, <50 °C, 5 min)/0.5 a | High-speed blender (10,000 rpm, 2 min), MSH (4 kpsi/9 kpsi, 5 times) | <400 nm/- | β-carotene bioaccessibility was found to decline progressively with a reduction in droplet size, with values dropping from approximately 59% (small emulsion) to 34% (large emulsion). | [87] |

| VD3 | HPH | Quillaja saponin (2 a) | Corn oil (10 a) | VD3 was dissolved in corn oil (−)/0.1 a | High-speed blender (2 min), HPH (12,000 psi, 3 cycles) | <400 nm/- | In vitro studies showed that the VD3 concentration of nanoemulsion was 3.94 times higher than traditional crude emulsion group. In vivo studies have shown that crude emulsion increases serum 25 (OH) VD levels by 36.04%, while supplementing VD with nanoemulsion increases VD levels by 73.10% | [88] |

| VD3 | MSH | Whey protein isolate (1 d) | Corn or mineral oil (10 a) | Vitamin D3 was dissolved in either corn oil (digestible oil) or mineral oil (indigestible oil) (−)/0.2 d | High-speed mixer (10,000 rpm, 2 min), MSH (12,000 psi, 5 times) | <170 nm/- | The extent of bioaccessibility was markedly greater in the nanoemulsions samples containing solely digestible oil (75.2%) compared to those with only indigestible oil (20.7%). | [89] |

| VD | HPH | Tween 20 (1 b) | STG or MCT/LCT (10 a) | Vitamin D was dissolved in STG or MCT/LCT (−)/0.1 a | High-speed ultra-Turrax blender (19.2 bar, 2 min), HPH (600 MPa, 5 cycles) | <200 nm/- | In comparison to MCT/LCT (45.40 ± 2.85%), STG (61.31 ± 2.90%) demonstrated a significantly greater VD bioaccessibility. | [90] |

| VD3 | HPH | Pea protein (2 a) | Flaxseed oil, corn oil, or fish oil (10 a) | Vitamin D3 was dissolved in oil phase (−)/1 a | High-shear blender (2 min), HPH (12,000 psi, 5 passes) | 200~550 nm/- | Vitamin bioaccessibility was notably superior in MUFA-emulsions (78%) compared with PUFA-emulsions (43%). | [57] |

| VD | USH | Tween 80 (20 c of buffer) | Corn oil20 a | Vitamin D was dissolved in corn oil (magnetic stirrer 30 min)/0.5 c of oil | High speed blender (10,000 rpm, 2 min), MSH (6000 psi, 15,000 psi, 3 times) | <600 nm/- | In vitro studies have demonstrated that the bioaccessibility of vitamin D is inversely related to droplet size. In vivo studies have indicated that emulsions with the largest droplet size have higher vitamin D absorption. | [91] |

| VE | MSH | Saponins (0.1 d) | Sunflower oil (10 d) | vitamin E was dissolved in sunflower oil (−)/2 d | High-speed homogenizer (15,500 rpm, 5 min), MSH (12,000 psi, four cycles) | 277 nm/- | The bioavailability of nanoemulsions is three times higher than that of traditional emulsions. | [92] |

| VE | MSH | Q-Natural® (1 d) | Corn oil (LCT) or MCT (10 d) | Vitamin E was dissolved in either corn oil (LCT) or MCT oil (−)/2.5 d | High-speed mixer (2 min), MSH (9000 psi, 4 cycles) | 228–270 nm/- | The bioaccessibility and conversion of a-tocopherol acetate to a-tocopherol was markedly greater in LCT (39% and 29%)-emulsions than in MCT (17% and 17%)-emulsions. | [51] |

| VE | MSH | Q-Naturale (0.5 d) | Corn oil (LCT) or MCT (10 a) | Vitamin E was dissolved in either corn oil (LCT) or MCT oil (−)/25 d | High-speed mixer (2 min), MSH (9000 psi, 5 cycles) | - | The bioaccessibility of LCT-emulsions (46%) than MCT-emulsions (19%) The conversion of α-tocopherol acetate to α-tocopherol was more pronounced in LCT (90%) than MCT (75%). | [93] |

| VE | MSH | Gum arabic or quillaja saponin or whey protein isolate (1.5 a) | Corn oil (10 a) | Vitamin E was dissolved in corn oil (−)/2 a | (−)/MSH (12,000 psi, 3 times) | - | The bioaccessibility of WPI-emulsions (85%) was higher for other two emulsions (65%). | [94] |

| VK1 | SE | Tween 80 (5–20%) | α-TOC | VK1 was dissolved in α-TOC (−)/5.48–10.52% | Organic phase slowly added into an aqueous phase under magnetic stirring at 700 rpm, stirred for 5 min at 1400 rpm. | <300 nm/(PDI < 0.2) | With the increases in the concentration of surfactant, there is a corresponding decline in droplets size. | [95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, T.; Song, F.; Yang, Z.; Yan, X.; Jiang, L.; Li, D.; Huang, Z. Nanoemulsion Encapsulation of Fat-Soluble Vitamins: Advances in Technology, Bioaccessibility and Applications. Foods 2026, 15, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010156

Zeng T, Song F, Yang Z, Yan X, Jiang L, Li D, Huang Z. Nanoemulsion Encapsulation of Fat-Soluble Vitamins: Advances in Technology, Bioaccessibility and Applications. Foods. 2026; 15(1):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010156

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Ting, Fei Song, Zhen Yang, Xianghui Yan, Lianzhou Jiang, Dongze Li, and Zhaoxian Huang. 2026. "Nanoemulsion Encapsulation of Fat-Soluble Vitamins: Advances in Technology, Bioaccessibility and Applications" Foods 15, no. 1: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010156

APA StyleZeng, T., Song, F., Yang, Z., Yan, X., Jiang, L., Li, D., & Huang, Z. (2026). Nanoemulsion Encapsulation of Fat-Soluble Vitamins: Advances in Technology, Bioaccessibility and Applications. Foods, 15(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010156