Valorization of Hericium erinaceus By-Products for β-Glucan Recovery via Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Alkaline Extraction and Prebiotic Potential Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

2.2. Proximate Analysis

2.3. Pretreatment with PEF and Extraction of Crude β-Glucan

2.4. Analysis of α and β-Glucan Contents

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.6. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.7. Evaluation of Prebiotic Potential

2.7.1. Analysis of Lactic Acid Bacterial Growth Promotion

2.7.2. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) Content

2.7.3. In Vitro Resistance to Gastric and Small Intestinal Digestion

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition

3.2. Effect of PEF, Hot Water, and Alkali on β-Glucan Extraction from H. erinaceus Mushroom By-Products

3.3. Microstructural Changes

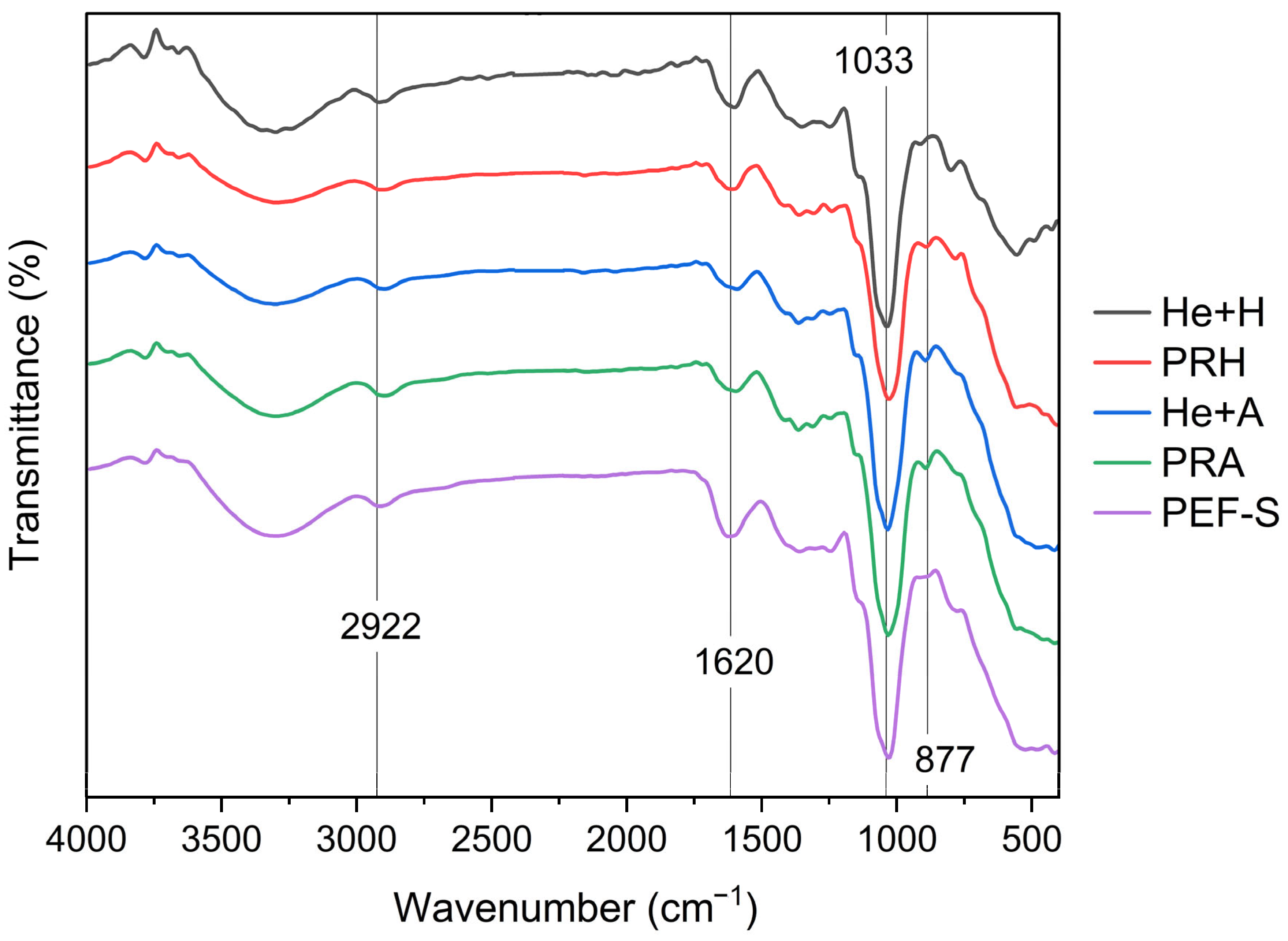

3.4. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy for Glucan Characterization

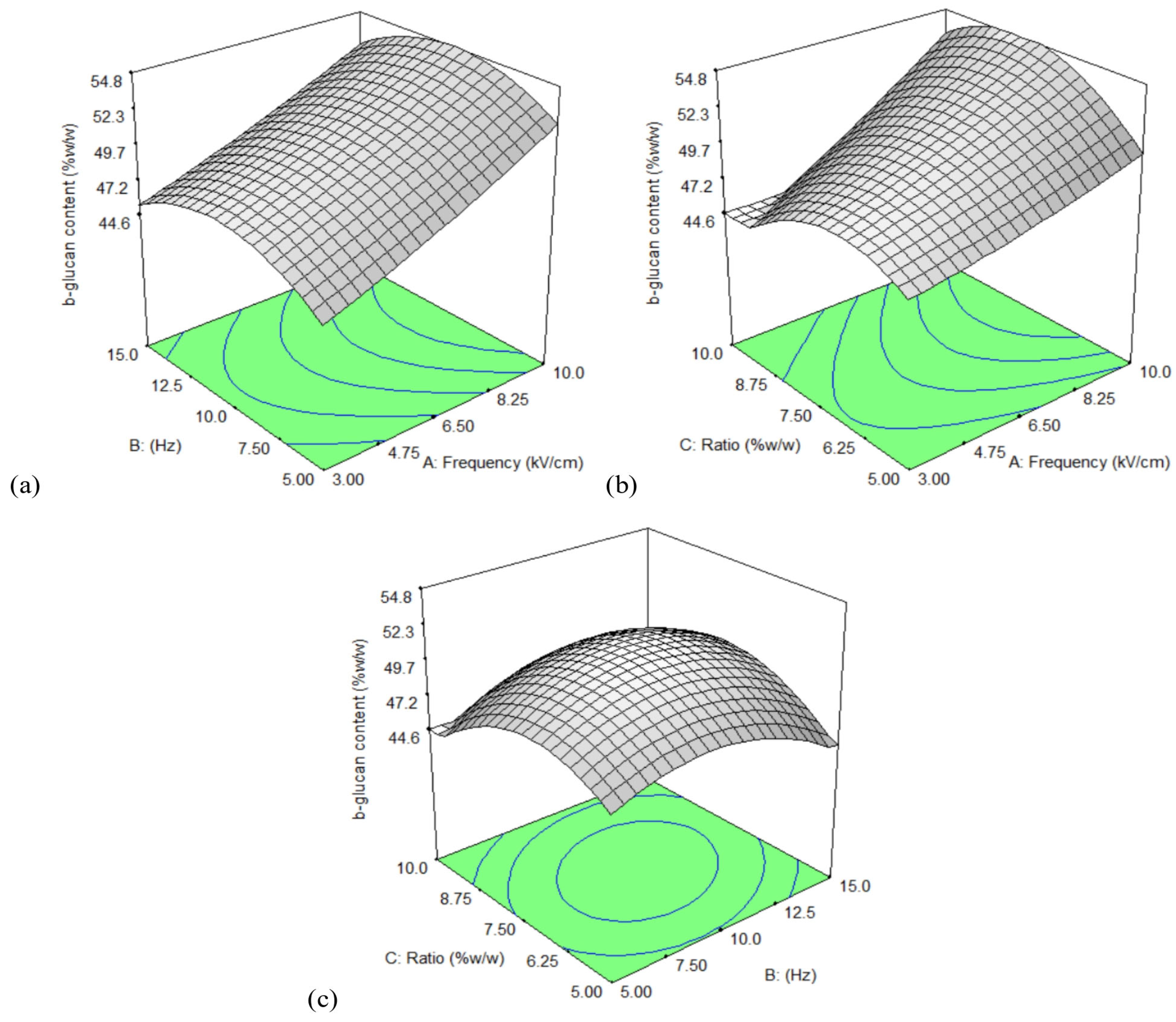

3.5. Optimization of Extraction Conditions Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

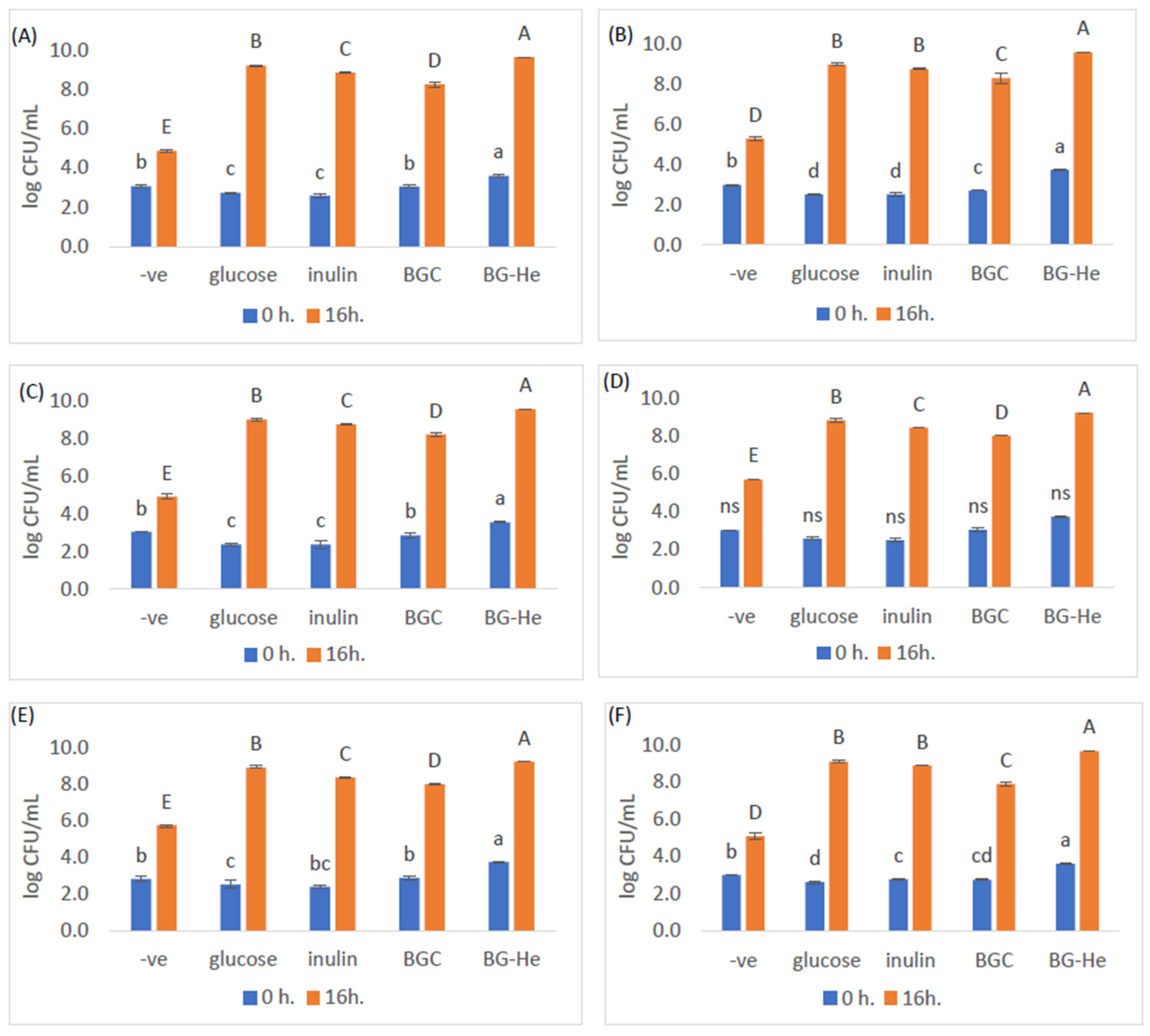

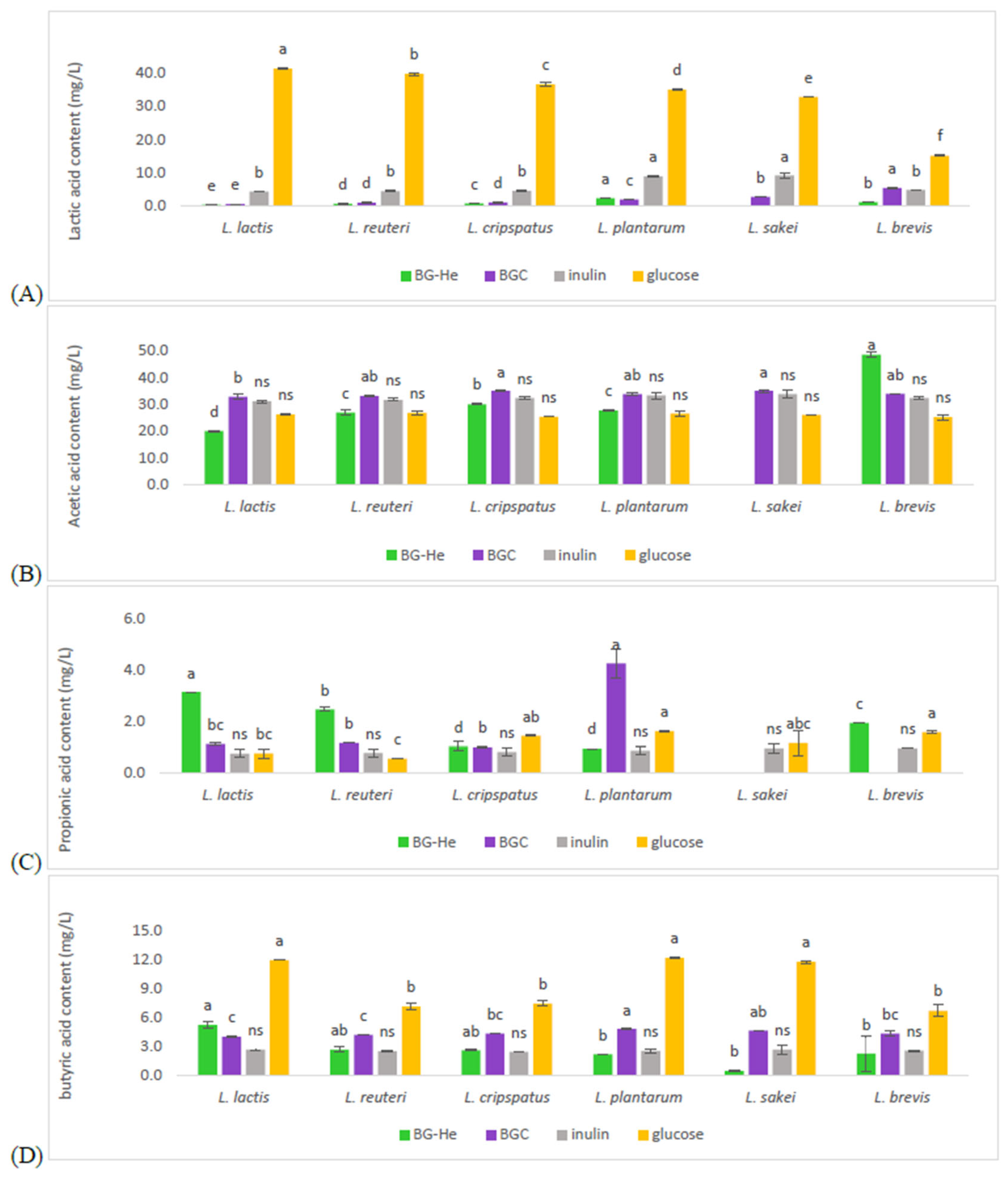

3.6. Lactic Acid Bacterial Growth Promotion

3.7. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Resistance of BG-He

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, M.A.; Tania, M.; Liu, R.; Rahman, M.M. Hericium erinaceus: An edible mushroom with medicinal values. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2013, 10, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, G.S.; De Andrade, P.; Field, R.A.; van Munster, J.M. Recent advances in enzymatic synthesis of β-glucan and cellulose. Carbohydr. Res. 2021, 508, 108411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, R.; Homayoonfal, M.; Malekjani, N.; Kharazmi, M.S.; Jafari, S.M. Interaction between β-glucans and gut microbiota: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 7804–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivieri, K.; de Oliveira, S.M.; de Souza Marquez, A.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Diniz, S.N. Insights on β-glucan as a prebiotic coadjuvant in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: A review. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2022, 2, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Zheng, F.; Zeng, X. Yeast β-glucan, a potential prebiotic, showed a similar probiotic activity to inulin. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10386–10396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatoi, H.; Singdevsachan, S.K.; Patra, J.K. Prebiotics and their production from unconventional raw materials (Mushrooms). In Therapeutic, Probiotic, and Unconventional Foods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chaikliang, C.; Wichienchot, S.; Youravoug, W.; Graidist, P. Evaluation on prebiotic properties of β-glucan and oligo-β-glucan from mushrooms by human fecal microbiota in fecal batch culture. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2015, 5, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, N. Chapter 13—The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Gut Microbiota: A Target for Dietary Intervention? In The Gut-Brain Axis; Hyland, N., Stanton, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, D.; Munekata, P.E.; Agregán, R.; Bermúdez, R.; López-Pedrouso, M.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Application of pulsed electric fields for obtaining antioxidant extracts from fish residues. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazanfari, N.; Yazdi, F.T.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Mohammadi, M. Using pulsed electric field pre-treatment to optimize coriander seeds essential oil extraction and evaluate antimicrobial properties, antioxidant activity, and essential oil compositions. LWT 2023, 182, 114852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobiev, E.; Lebovka, N. Selective extraction of molecules from biomaterials by pulsed electric field treatment. In Handbook of Electroporation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 655–670. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, V.; Dimopoulos, G.; Dermesonlouoglou, E.; Taoukis, P. Application of pulsed electric fields to improve product yield and waste valorization in industrial tomato processing. J. Food Eng. 2020, 270, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, S.; Waterhouse, G.I.; Zhou, T.; Xu, F.; Wang, R.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Wu, P. High-intensity pulsed electric field-assisted acidic extraction of pectin from citrus peel: Physicochemical characteristics and emulsifying properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 146, 109291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Kalompatsios, D.; Mantiniotou, M.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Pulsed electric field applications for the extraction of bioactive compounds from food waste and by-products: A critical review. Biomass 2023, 3, 367–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thikham, S.; Jeenpitak, T.; Shoji, K.; Phongthai, S.; Therdtatha, P.; Yawootti, A.; Klangpetch, W. Pulsed electric field-assisted extraction of mushroom ß-glucan from Pleurotus pulmonarius by-product and study of prebiotic properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 3939–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ookushi, Y.; Sakamoto, M.; Azuma, J.-i. Extraction of. BETA.-Glucan from the Water-insoluble Residue of Hericium erinaceum with Combined Treatments of Enzyme and Microwave Irradiation. J. Appl. Glycosci. 2008, 55, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiderle, F.R.; Alquini, G.; Tadra-Sfeir, M.Z.; Iacomini, M.; Wichers, H.J.; Van Griensven, L.J. Agaricus bisporus and Agaricus brasiliensis (1,6)-β-D-glucans show immunostimulatory activity on human THP-1 derived macrophages. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCleary, B.V.; Draga, A. Measurement of β-glucan in mushrooms and mycelial products. J. AOAC Int. 2016, 99, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Baere, S.; Eeckhaut, V.; Steppe, M.; De Maesschalck, C.; De Backer, P.; Van Immerseel, F.; Croubels, S. Development of a HPLC–UV method for the quantitative determination of four short-chain fatty acids and lactic acid produced by intestinal bacteria during in vitro fermentation. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013, 80, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food–an international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonkhom, D.; Luangharn, T.; Stadler, M.; Thongklang, N. Cultivation and Nutrient Compositions of Medicinal Mushroom, Hericium erinaceus in Thailand. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2024, 51, e2024028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.N.; Chang, C.S.; Yang, M.F.; Chen, S.; Soni, M.; Mahadevan, B. Subchronic toxicity and genotoxicity studies of Hericium erinaceus β-glucan extract preparation. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 3, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshyaran, A.; Babaeipour, V.; Deldar, A.A.; Mirzaei, M.; Khosravi Darani, K. Development of a High-Yield Process for Scalable Extraction of Beta-Glucan from Baker’s Yeast. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2024, 43, 3488–3497. [Google Scholar]

- Sakdasri, W.; Arnutpongchai, P.; Phonsavat, S.; Bumrungthaichaichan, E.; Sawangkeaw, R. Pressurized hot water extraction of crude polysaccharides, β-glucan, and phenolic compounds from dried gray oyster mushroom. LWT 2022, 168, 113895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.U.; Ko, M.J.; Chung, M.S. Hydrolysis of beta-glucan in oat flour during subcritical-water extraction. Food Chem. 2020, 308, 125670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radnia, M.R.; Mahdian, E.; Sani, A.M.; Hesarinejad, M.A. Comparison of microwave and pulsed electric field methods on extracting antioxidant compounds from Arvaneh plant (Hymenocrater platystegius Rech. F). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.M.; Delso, C.; Alvarez, I.; Raso, J. Pulsed electric field-assisted extraction of valuable compounds from microorganisms. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 530–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktas-Akyildiz, E.; Sibakov, J.; Nappa, M.; Hytönen, E.; Koksel, H.; Poutanen, K. Extraction of soluble β-glucan from oat and barley fractions: Process efficiency and dispersion stability. J. Cereal Sci. 2018, 81, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano Pérez, A.S.; Lozada Castro, J.J.; Guerrero Fajardo, C.A. Application of microwave energy to biomass: A comprehensive review of microwave-assisted technologies, optimization parameters, and the strengths and weaknesses. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.M.; Free, S.J. The structure and synthesis of the fungal cell wall. Bioessays 2006, 28, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carullo, D.; Abera, B.D.; Casazza, A.A.; Donsì, F.; Perego, P.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G. Effect of pulsed electric fields and high pressure homogenization on the aqueous extraction of intracellular compounds from the microalgae Chlorella vulgaris. Algal Res. 2018, 31, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja-Gómez, M.; Castagnini, J.M.; Carbó, E.; Ferrer, E.; Berrada, H.; Barba, F.J. Evaluation of Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Extraction on the Microstructure and Recovery of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds from Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Separations 2022, 9, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putranto, A.W.; Abida, S.H.; Adrebi, K.; Harianti, A. Lignocellulosic Analysis of Corncob Biomass by Using Non-Thermal Pulsed Electric Field-NaOH Pretreatment. Reaktor 2020, 20, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šandula, J.; Kogan, G.; Kačuráková, M.; Machová, E. Microbial (1→3)-β-d-glucans, their preparation, physico-chemical characterization and immunomodulatory activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 1999, 38, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, A.T.; Lee, J.; Milanovich, F.P. Laser-Raman spectroscopic study of cyclohexaamylose and related compounds: Spectral analysis and structural implications. Carbohydr. Res. 1979, 76, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Han, H.; Fan, H.; Xiao, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, G. Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro release analysis of a novel glucan-based polymer carrier. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2018, 296, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.F.; Gaspar, E.M. Simultaneous chromatographic separation of enantiomers, anomers and structural isomers of some biologically relevant monosaccharides. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1188, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, P.; Lopez, P.; Capozzi, V.; De Palencia, P.F.; Duenas, M.T.; Spano, G.; Fiocco, D. Beta-glucans improve growth, viability and colonization of probiotic microorganisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 6026–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ou, J.; Luo, Z.; Kim, I.H. Effect of dietary β-1, 3-glucan supplementation and heat stress on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, meat quality, organ weight, ileum microbiota, and immunity in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 4969–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, K.H.; Jang, K.-H.; Kang, S.A. Effects of Dietary β-Glucan on Short Chain Fatty Acids Composition and Intestinal Environment in Rats. Korean J. Food Nutr. 2016, 29, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, W.; Fan, M.; Qian, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Systematic assessment of oat β-glucan catabolism during in vitro digestion and fermentation. Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Bhardwaj, A. β-glucans: A potential source for maintaining gut microbiota and the immune system. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1143682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, B.A.; Kebede, B. Probiotics, their prophylactic and therapeutic applications in human health development: A review of the literature. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoukat, M.; Sorrentino, A. Cereal β-glucan: A promising prebiotic polysaccharide and its impact on the gut health. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 2088–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, A.; Rigby, N.; Harvey, P.; Bajka, B. Increasing dietary oat fibre decreases the permeability of intestinal mucus. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 26, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Yield (g/100 g) | β-Glucan Content (% w/w) |

|---|---|---|

| He | 43.54 ± 0.64 c | |

| PEF-S | 3.43 ± 0.43 b | 25.73 ± 4.63 d |

| PRH | 4.73 ± 1.38 b | 68.05 ± 4.24 a |

| PRA | 25.00 ± 2.96 a | 56.93 ± 5.07 b |

| Factor | Symbol | Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (−1) | Intermediate (0) | High (+1) | ||

| Electric field strength (kV/cm) | A | 3 | 6.5 | 10 |

| Frequency (Hz) | B | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| Mushroom/water ratio (% w/w) | C | 5 | 7.5 | 10 |

| Value | Optimized Process Parameters | Response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electric Field Strength (kV/cm) | Frequency (Hz) | Ratio (% w/v) | β-Glucan (% w/w) | |

| Predicted | 9.99 | 12.2 | 8.44 | 54.80 |

| Actual | 10 | 12 | 8.44 | 50.14 ± 1.36 |

| Error (%) | 0.10 | 1.64 | 0.00 | 8.51 |

| Sample | Hydrolysis (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gastric Phase | Small Intestine Phase | |

| BG-He | 9.26 ± 0.79 a | 16.55 ± 1.11 a |

| BGC | 1.82 ± 0.31 c | 11.01 ± 2.13 b |

| Inulin | 6.88 ± 0.29 b | 16.89 ± 0.60 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jeenpitak, T.; Pattarapisitporn, A.; Tangjaidee, P.; Khumsap, T.; Yawootti, A.; Phongthai, S.; Noma, S.; Klangpetch, W. Valorization of Hericium erinaceus By-Products for β-Glucan Recovery via Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Alkaline Extraction and Prebiotic Potential Analysis. Foods 2026, 15, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010145

Jeenpitak T, Pattarapisitporn A, Tangjaidee P, Khumsap T, Yawootti A, Phongthai S, Noma S, Klangpetch W. Valorization of Hericium erinaceus By-Products for β-Glucan Recovery via Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Alkaline Extraction and Prebiotic Potential Analysis. Foods. 2026; 15(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeenpitak, Tannaporn, Alisa Pattarapisitporn, Pipat Tangjaidee, Tabkrich Khumsap, Artit Yawootti, Suphat Phongthai, Seiji Noma, and Wannaporn Klangpetch. 2026. "Valorization of Hericium erinaceus By-Products for β-Glucan Recovery via Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Alkaline Extraction and Prebiotic Potential Analysis" Foods 15, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010145

APA StyleJeenpitak, T., Pattarapisitporn, A., Tangjaidee, P., Khumsap, T., Yawootti, A., Phongthai, S., Noma, S., & Klangpetch, W. (2026). Valorization of Hericium erinaceus By-Products for β-Glucan Recovery via Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Alkaline Extraction and Prebiotic Potential Analysis. Foods, 15(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010145