Comparative Study on the In Vitro Fermentation Characteristics of Three Plant-Derived Polysaccharides with Different Structural Compositions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Component Analysis of Polysaccharides

2.3. Structural Characteristics Analysis of Polysaccharides

2.4. Monosaccharide Composition and Molecular Weight Distribution of Polysaccharides Analysis

2.5. Morphological Characteristics Analysis of Polysaccharides

2.6. Antioxidant Activity Analysis

2.7. In Vitro Fermentation of Polysaccharides

2.7.1. Colony Collection and In Vitro Fermentation Modelling

2.7.2. Measurements of Gas Production, OD600, pH, and Sugar Content During the Fermentation Process

2.7.3. Determination of SCFAs During Fermentation

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Composition Analysis of Different Polysaccharides

3.2. Structural Characteristics Analysis of Different Polysaccharides

3.3. Morphological Characteristics Analysis of Different Polysaccharides

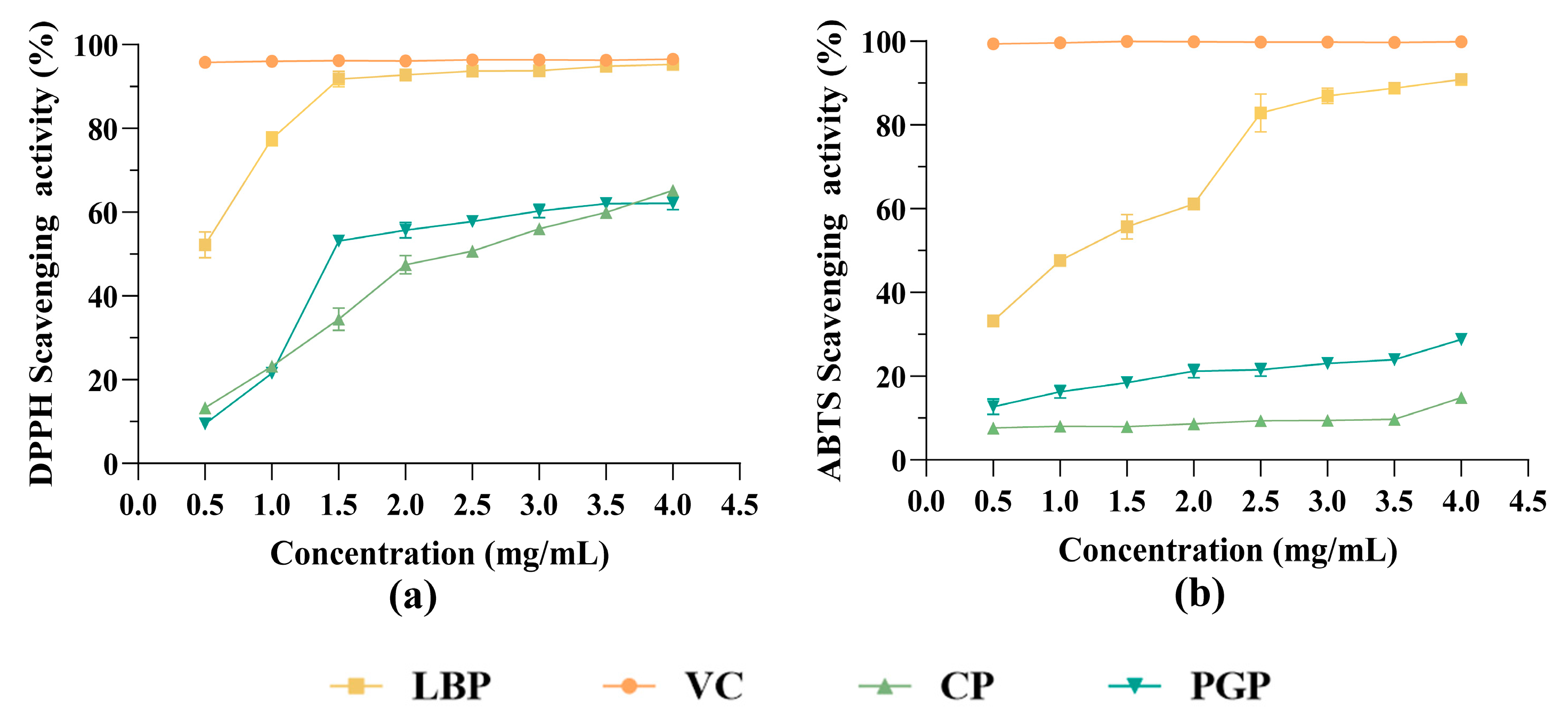

3.4. Antioxidant Activity Analysis of Different Polysaccharides

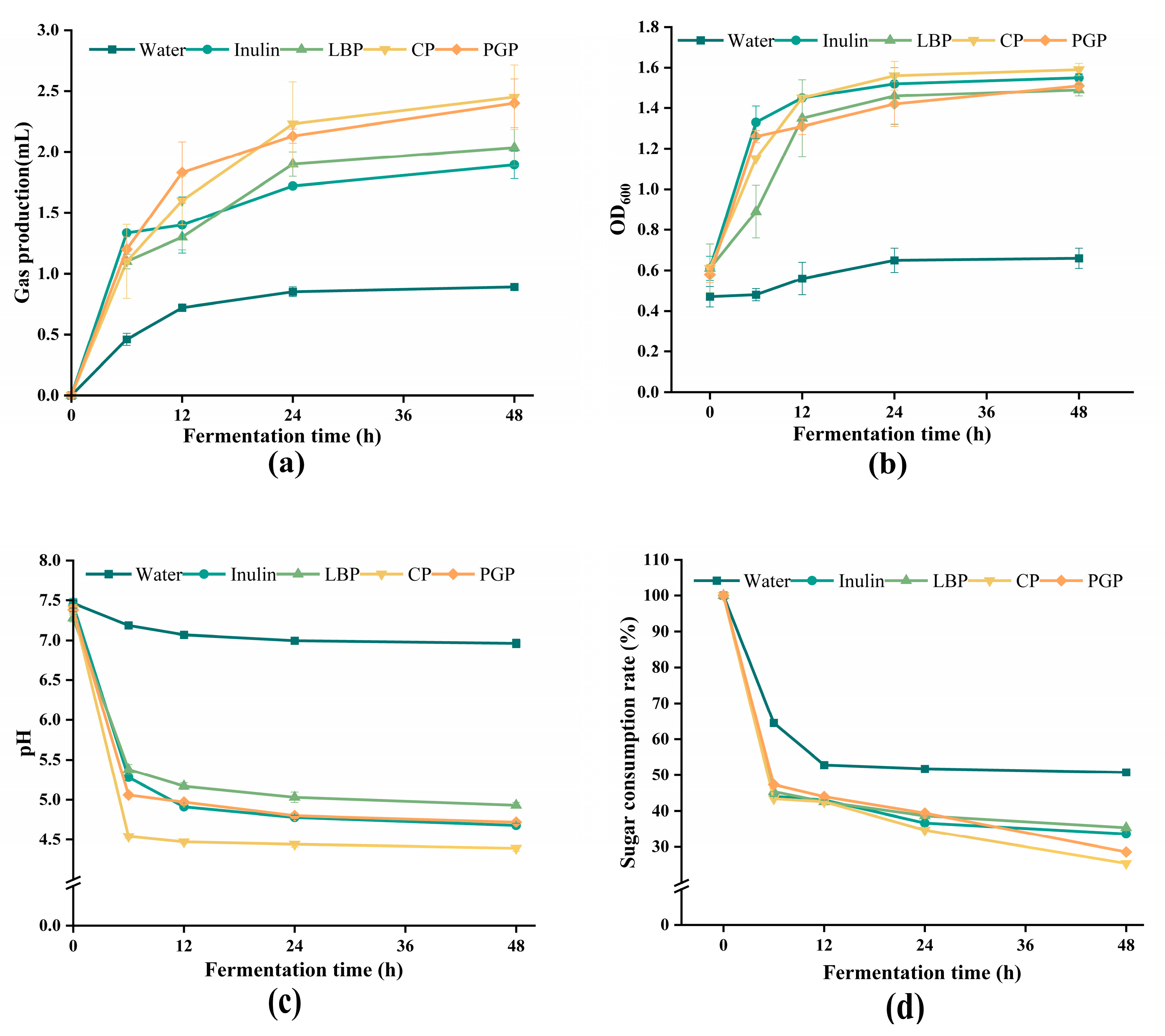

3.5. In Vitro Fermentation Analysis of Different Polysaccharides

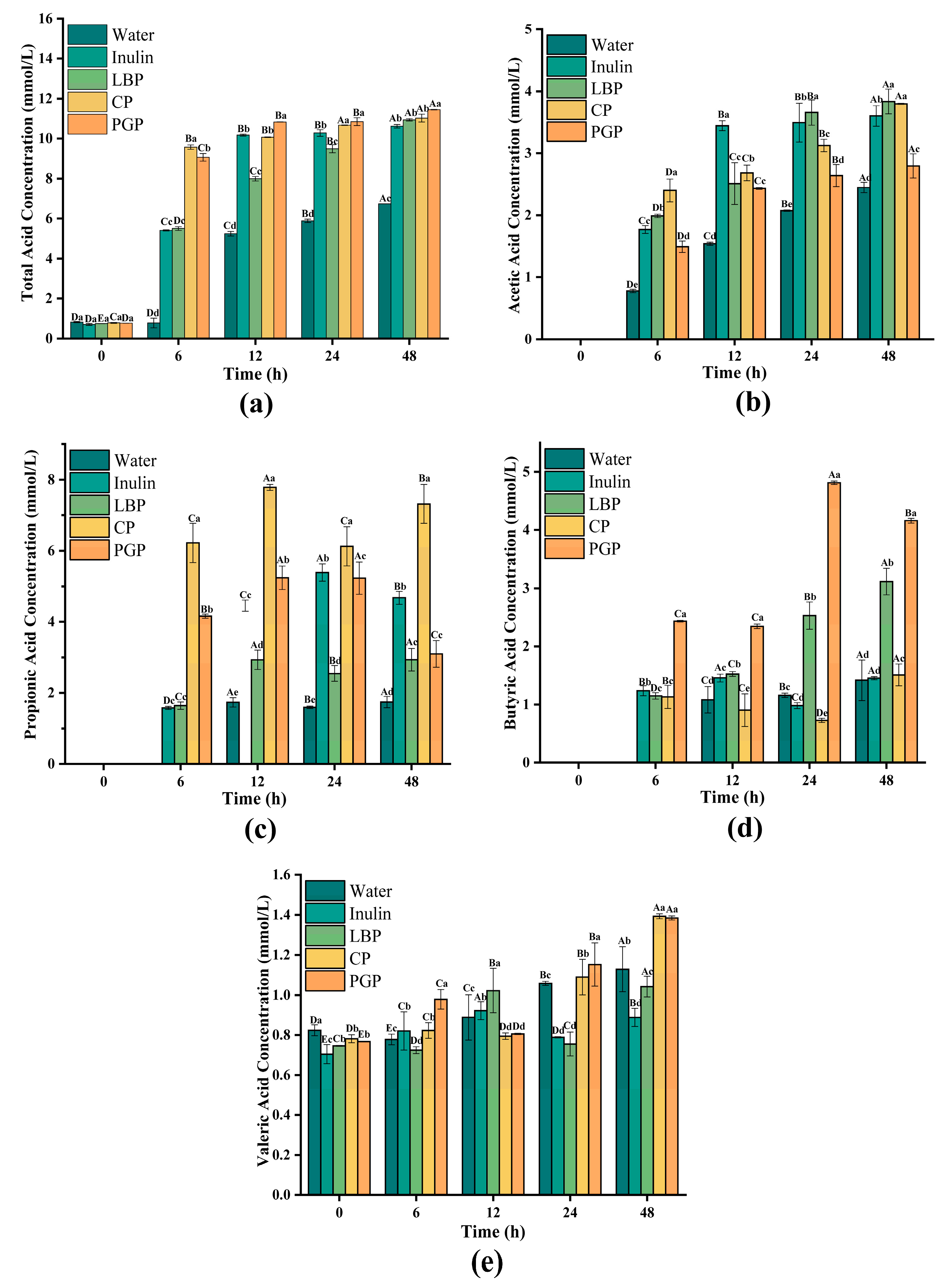

3.6. SCFAs Production Analysis During Fermentation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhou, J.; Duan, Y.; Kong, T.; Ma, H.; Zhang, H. Recent progress of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides on intestinal microbiota, microbial metabolites and health: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 2917–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nai, J.; Zhang, C.; Shao, H.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Gao, L.; Dai, M.; Zhu, L.; Sheng, H. Extraction, structure, pharmacological activities and drug carrier applications of Angelica sinensis polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 2337–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L. The structures and biological functions of polysaccharides from traditional Chinese herbs. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 163, 423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh, M.; Keshavarz Lelekami, A.; Khedmat, L. Plant/algal polysaccharides extracted by microwave: A review on hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, prebiotic, and immune-stimulatory effect. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 266, 118134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, T.K.O.; da Silva, F.F.A.; Bernardes, E.S.; Paulo Fabi, J. Plant-derived polyphenolic compounds: Nanodelivery through polysaccharide-based systems to improve the biological properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 11894–11918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, P.; Zeng, X.; Kang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xie, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Efficient adsorption of methylene blue by xanthan gum derivative modified hydroxyapatite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenas, I.; Camacho-Barcia, L.; Miranda-Olivos, R.; Solé-Morata, N.; Misiolek, A.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F. Probiotic and prebiotic interventions in eating disorders: A narrative review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2024, 32, 1085–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Yu, D.; Chen, X.; Song, G. Preparation, characterization and controlled-release property of Fe3+ cross-linked hydrogels based on peach gum polysaccharide. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y. Chemical structure and prebiotic activity of a Dictyophora indusiata polysaccharide fraction. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobden, M.R.; Martin-Morales, A.; Guérin-Deremaux, L.; Wils, D.; Costabile, A.; Walton, G.E.; Rowland, I.; Kennedy, O.B.; Gibson, G.R. In vitro fermentation of NUTRIOSE® FB06, a wheat dextrin soluble fibre, in a continuous culture human colonic model system. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.M.; Raqib, R.; Huda, M.N.; Alam, M.J.; Monirujjaman, M.; Akhter, T.; Wagatsuma, Y.; Qadri, F.; Zerofsky, M.S.; Stephensen, C.B. High-Dose Neonatal vitamin a supplementation transiently decreases thymic function in early infancy. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaninia, M.H.; Yan, N. Catalyst-free pH-responsive chitosan-based dynamic covalent framework materials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 301, 120332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zeng, R.; Tang, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, C. The “crosstalk” between microbiota and metabolomic profile in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice supplemented with Bletilla striata polysaccharides and composite polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashi, T.; Taharabaru, T.; Motoyama, K. Synthesis of cyclodextrin-based polyrotaxanes and polycatenanes for supramolecular pharmaceutical sciences. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 337, 122143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Jiang, F.; Cong, H.; Zhu, S. Molecular weight determination of low molecular weight hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate by gel permeation chromatography. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 311, 120488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Zhang, G.; Li, S.; Gong, H.; Liu, M.; Dai, X. Structure characteristics of low molecular weight pectic polysaccharide and its anti-aging capability by modulating the intestinal homeostasis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 303, 120467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumpf, J.; Burger, R.; Schulze, M. Statistical evaluation of DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and Folin-Ciocalteu assays to assess the antioxidant capacity of lignins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Jing, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, B.; Hu, H.; Cong, H.; Shen, Y. A chitosan derivative-crosslinked hydrogel with controllable release of polydeoxyribonucleotides for wound treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel, G.; David, L. Induction of human trophoblast stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 2760–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Shim, Y.S.; Lee, K.G. Determination of alcohols in various fermented food matrices using gas chromatography-flame ionization detector for halal certification. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 31, 1639–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soylak, M.; Uzcan, F.; Goktas, O.; Gumus, Z.P. Fe3O4-SiO2-MIL-53 (Fe) nanocomposite for magnetic dispersive micro-solid phase extraction of cadmium (II) at trace levels prior to HR-CS-FAAS detection. Food Chem. 2023, 429, 136855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, R.M.; Adessi, A.; Caldara, F.; De Philippis, R.; Dalla Valle, L.; La Rocca, N. In vivo anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of microbial polysaccharides extracted from Euganean therapeutic muds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 1710–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, A.; Jin, C.; Li, M.; Ding, K. RG-I pectin-like polysaccharide from Rosa chinensis inhibits inflammation and fibrosis associated to HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway to improve non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 337, 122139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Wang, B.; Lv, W.; Li, B.; Xiao, H.; Lin, R. Physicochemical properties, structure and biological activity of ginger polysaccharide: Effect of microwave infrared dual-field coupled drying. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezus, B.; Esquivel, J.C.C.; Cavalitto, S.; Cavello, I. Pectin extraction from lime pomace by cold-active polygalacturonase-assisted method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidetzky, B.; Zhong, C. Phosphorylase-catalyzed bottom-up synthesis of short-chain soluble cello-oligosaccharides and property-tunable cellulosic materials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 51, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z.; Tan, C. Morphology, Morphology, Solid structure and antioxidant activity in vitro of Angelica sinensis polysaccharide-Ce(IV). Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202200813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swackhamer, C.; Jang, S.; Park, B.R.; Hamaker, B.R.; Jung, S.K. Structure-based standardization of prebiotic soluble dietary fibers based on monosaccharide composition, degree of polymerization, and linkage composition. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 367, 123949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X. Interfacial structure modification and enhanced emulsification stability of microalgae protein through interaction with anionic polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.Y.; Lam, K.L.; Li, X.; Kong, A.P.; Cheung, P.C. Circadian disruption-induced metabolic syndrome in mice is ameliorated by oat β-glucan mediated by gut microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 267, 118216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.A.R.; Coimbra, M.A. The antioxidant activity of polysaccharides: A structure-function relationship overview. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 314, 120965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bai, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kan, J.; Jin, C. Isolation, structural characterization and bioactivities of naturally occurring polysaccharide-polyphenolic conjugates from medicinal plants—A reivew. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 2242–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wen, C.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Y. Review of isolation, structural properties, chain conformation, and bioactivities of psyllium polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xiao, X.; Yu, W.; Yu, B.; He, J.; Zheng, P.; Yu, J.; Luo, J.; Luo, Y.; Yan, H.; et al. Yucca schidigera purpurea-sourced arabinogalactan polysaccharides augments antioxidant capacity facilitating intestinal antioxidant functions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 326, 121613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Deji; Zhu, M.; Chen, D.; Lu, Y. Juniperus pingii var. wilsonii acidic polysaccharide: Extraction, characterization and anticomplement activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 231, 115728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Zhang, R.; You, L.; Ma, Y.; Liao, L.; Pedisić, S. In vitro fermentation characteristics of polysaccharide from Sargassum fusiforme and its modulation effects on gut microbiota. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2021, 151, 112145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, L. In vitro dynamic digestion properties and fecal fermentation of Dictyophora indusiata polysaccharide: Structural characterization and gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Hong, Z.; Wong, K.H.; Chiou, J.C.; Xu, B.; Cespedes-Acuña, C.L.; Bai, W.; Tian, L. Structural characteristics and in vitro fermentation patterns of polysaccharides from Boletus mushrooms. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 7912–7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Bai, Y.; Dong, L.; Liu, L.; Jia, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M. Structural characterization and in vitro gastrointestinal digestion and fermentation of litchi polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Pang, B.; Yan, X.; Shang, X.; Hu, X.; Shi, J. Prebiotic properties of different polysaccharide fractions from Artemisia sphaerocephala Krasch seeds evaluated by simulated digestion and in vitro fermentation by human fecal microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.H.; Huang, S.C.; Hou, C.Y.; Chen, Y.Z.; Chen, Y.H.; Hakkim Hazeena, S.; Hsu, W.H. Effect of polysaccharide derived from dehulled adlay on regulating gut microbiota and inhibiting Clostridioides difficile in an in vitro colonic fermentation model. Food Chem. 2023, 410, 135410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, B.; Zhao, C.; Wang, M. Integrated microbiota and metabolite profiling analysis of prebiotic characteristics of Phellinus linteus polysaccharide in vitro fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Hong, R.; Yi, Y.; Bai, Y.; Dong, L.; Jia, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.; Wu, J. In vitro digestion and human gut microbiota fermentation of longan pulp polysaccharides as affected by Lactobacillus fermentum fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangan, R.J.; Alsina, F.C.; Mosti, F.; Sotelo-Fonseca, J.E.; Snellings, D.A.; Au, E.H.; Carvalho, J.; Sathyan, L.; Johnson, G.D.; Reddy, T.E.; et al. Adaptive sequence divergence forged new neurodevelopmental enhancers in humans. Cell 2022, 185, 4587–4603.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Peng, D.; Kasimumali, A.; Rong, S. Gut microbial metabolites SCFAs and chronic kidney disease. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorbara, M.T.; Dubin, K.; Littmann, E.R.; Moody, T.U.; Fontana, E.; Seok, R.; Leiner, I.M.; Taur, Y.; Peled, J.U.; van den Brink, M.R.M.; et al. Inhibiting antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae by microbiota-mediated intracellular acidification. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Iersel, L.E.J.; Beijers, R.; Simons, S.O.; Schuurman, L.T.; Shetty, S.A.; Roeselers, G.; van Helvoort, A.; Schols, A.; Gosker, H.R. Characterizing gut microbial dysbiosis and exploring the effect of prebiotic fiber supplementation in patients with COPD. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovalino-Córdova, A.M.; Fogliano, V.; Capuano, E. In vitro colonic fermentation of red kidney beans depends on cotyledon cells integrity and microbiota adaptation. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 4983–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ye, B.; Ma, J.H.; Ji, S.; Sheng, W.; Ye, S.; Ou, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Sodium butyrate ameliorates diabetic retinopathy in mice via the regulation of gut microbiota and related short-chain fatty acids. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.W.; Huang, Z.Q.; Liu, K.; Li, D.Z.; Mo, T.L.; Liu, Q. The role of intestinal microbiota and metabolites in intestinal inflammation. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 288, 127838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Monosaccharide | LBP | CP | PGP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rha (%) | 21.73 ± 0.3 a | 0.44 ± 0.43 c | 2.05 ± 0.05 b |

| Ara (%) | 2.49 ± 0.34 b | NA | 26.38 ± 0.15 a |

| Gal (%) | 33.08 ± 1.24 a | 13.04 ± 0.01 c | 19.62 ± 0.23 b |

| Glc (%) | 18.91 ± 0.6 c | 70.77 ± 0.69 a | 51.60 ± 0.12 b |

| Man (%) | 0.60 ± 0.12 b | 14.02 ± 0.87 a | NA |

| Glca (%) | NA | NA | 0.35 ± 0.04 a |

| Gala (%) | 20.78 ± 1.39 a | 1.24 ± 1.44 b | NA |

| Samples | LBP | CP | PGP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral sugars | 46.47 ± 5.03% b | 87.05 ± 0.42% a | 80.06 ± 0.15% a |

| Acid sugars | 36.76 ± 4.63% a | 9.34 ± 0.64% b | 6.61 ± 0.12% b |

| Mw (×104 g/mol) | 6.57 ± 0.30 b | 3.40 ± 0.15 c | 37.92 ± 0.58 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Hu, J. Comparative Study on the In Vitro Fermentation Characteristics of Three Plant-Derived Polysaccharides with Different Structural Compositions. Foods 2026, 15, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010137

Gao X, Zhao X, Huang J, Liu H, Hu J. Comparative Study on the In Vitro Fermentation Characteristics of Three Plant-Derived Polysaccharides with Different Structural Compositions. Foods. 2026; 15(1):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010137

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Xingyue, Xinming Zhao, Jie Huang, Huan Liu, and Jielun Hu. 2026. "Comparative Study on the In Vitro Fermentation Characteristics of Three Plant-Derived Polysaccharides with Different Structural Compositions" Foods 15, no. 1: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010137

APA StyleGao, X., Zhao, X., Huang, J., Liu, H., & Hu, J. (2026). Comparative Study on the In Vitro Fermentation Characteristics of Three Plant-Derived Polysaccharides with Different Structural Compositions. Foods, 15(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010137