1. Introduction

Sulfonamides are among the most extensively utilized classes of veterinary antibiotics in global poultry production due to their broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and cost-effectiveness [

1]. In particular, the widespread use of sulfathiazole in poultry breeding has raised concerns regarding its residues in poultry-derived products, posing potential risks to human health and food safety due to the improper use and insufficient withdrawal periods [

1,

2]. Some regulatory agencies in the worldwide, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), have set stringent maximum residue limits (MRLs) for sulfathiazole in poultry tissues to mitigate antimicrobial resistance and toxicological hazards [

2]. Although conventional detection methods such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for sulfonamides can offer excellent sensitivity and accuracy, they are associated with several practical limitations. These include laborious sample preparation, reliance on skilled personnel, high costs, and prolonged analysis times [

2,

3,

4]. The analysis time often exceeds 30 min per sample, making them unsuitable for screening or on-site detection scenarios. These limitations highlight the urgent need for developing rapid, cost-effective alternatives for routine monitoring of sulfathiazole residues in chicken blood.

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a promising alternative due to its rapid response, high sensitivity and molecular specificity [

5]. By leveraging plasmonic enhancement from metallic nanoparticles (e.g., gold or silver colloids), SERS technology can be used to detect trace analytes in complex matrices without the need for extensive purification [

6]. Recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of SERS for detecting sulfonamides in various environmental and food samples, including milk, honey and muscle tissues [

7,

8]. Its key advantages included minimal sample preparation, rapid analysis (typically 5 to 15 min), and the ability to provide molecular fingerprint information for unambiguous identification [

9,

10]. However, several challenges impede the reliable detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, primarily due to the inherent complexity of the matrix (e.g., proteins, lipids and cellular debris) and the lack of universal colloidal substrates (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles) tailored for this application.

In this study, we systematically optimized the SERS detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood by examining two aspects: the colloidal substrate system and detection parameters. Four types of colloidal substrates, i.e., gold colloid A, gold colloid B, gold colloid C and silver colloids, were evaluated for their enhancement performance. Key experimental parameters, including electrolyte type, colloidal dosage, NaCl solution dosage, adsorption time and spectral preprocessing strategies, were systematically investigated to maximize signal-to-noise ratios and minimize matrix interference. Furthermore, a prediction model integrating genetic algorithm (GA) and support vector regression (SVR) was developed to detect sulfathiazole in chicken blood. This approach aims to offer a rapid, cost-effective, and portable method for on-site screening of sulfathiazole residues in chicken blood, aligning with global food safety initiatives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

Chicken whole blood was procured from a local market at Jiangxi Agricultural University in multiple batches to ensure sample diversity and representativeness. Selected chicken blood samples were submitted to a certified testing laboratory for analysis, and the test report confirmed the absence of detectable sulfathiazole residues in the chicken blood.

All chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade or higher, unless stated otherwise. Sulfathiazole (98%, Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), food-grade sodium citrate (~99%, Shandong Ensign Industrial Co., Ltd., Weifang, China), tetrachloroauric acid trihydrate (≥49.0%, Sigma-Aldrich Trading Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), silver nitrate (≥99.8%, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and formic acid solution (98%, Shandong Keyuan Biochemical Co., Ltd., Heze, China) were used in this study. Anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4, ≥98%), sodium chloride (NaCl, ≥99.5%), calcium chloride (CaCl2, ≥99.5%) and acetonitrile solution (≥99.5%) were purchased from Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., Shantou, China.

2.2. Instruments and Equipment

A portable Raman spectroscopy acquisition system was composed of QE65 Pro Raman spectrometer (Ocean Insight, Orlando, FL, USA), 785 nm laser (Ocean Insight, USA), fiber optics, a sampling accessory and a computer. A thermostatic water bath (WB100-4F, JOANLAB Equipment Co., Ltd., Huzhou, China), an electronic balance (FA2004, Shanghai Sunny Hengping Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), an intelligent constant-temperature magnetic stirrer (ZNCL-T, Gongyi Chuanyuan Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Gongyi, China), a digital ultrasonic cleaner (KQ-500DE, Kunshan Ultrasonic Instrument Co., Ltd., Kunshan, China), a high-speed centrifuge (PK-165, Hunan Pingke Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Changsha, China), and a vortex mixer (VORTEX-6, Haimen Kylin-Bell Lab Instruments Co., Ltd., Haimen, China) were employed in the work.

2.3. Preparation of Standard Solutions

1 mL formic acid solution was diluted to 1000 mL with acetonitrile solution by thorough mixing to obtain 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. 5 mg of sulfathiazole standard was ultrasonically dissolved in 100 mL ultrapure water to yield a 50 mg/L sulfathiazole standard solution. During experiments, the above sulfathiazole standard solution was diluted with ultrapure water to prepare sulfathiazole solutions of various concentrations.

2.4. Preparation of Chicken Blood Samples

Firstly, 100 mL of food-grade sodium citrate solution (10 g/L) was mixed with chicken whole blood at a volume ratio of 1:3 (anticoagulant–blood) and stored at low temperature for subsequent use. Next, 8 mL of chicken whole blood was combined with 2 mL of sulfathiazole standard solutions at varying concentrations in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. The mixture underwent vortex mixing for 2 min followed by ultrasonic agitation for 5 min to obtain chicken blood samples containing different concentrations of sulfathiazole. Following this, 2 mL of the prepared chicken blood was combined with 2 mL of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile solution. The above mixture was vortexed for 30 s followed by ultrasonic agitation for 10 min and centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane for downstream analytical procedures.

2.5. Preparation of Colloidal Substrates

The synthesis of gold colloid A was based upon a published protocol with slight modifications [

11]. To prepare gold colloid A, a three-necked round-bottom flask containing 150 mL of 2.2 mM trisodium citrate solution was heated to boiling under reflux conditions. Upon reaching boiling, 1 mL of 25 mM HAuCl

4 solution was rapidly added, resulting in a color change from yellow to pale pink after 10 min. The reaction mixture was then maintained at 90 °C, and 1 mL of 60 mM trisodium citrate solution was immediately introduced. Subsequently, 1 mL of 25 mM HAuCl

4 solution was added after a 2 min interval. After 30 min, 2 mL of the above solution was withdrawn. After repeating the aforementioned procedure at 90 °C for 13 times, the resulting colloidal solution was cooled to room temperature to yield gold colloid A, hereafter referred to as such throughout this study.

Gold colloid B was synthesized following the modified Frens protocol [

12]. 100 mL of 1 mM HAuCl

4 solution was heated to boiling, and 3.7 mL of 1% trisodium citrate solution was rapidly injected into the boiling solution, followed by continuous stirring and heating for 30 min. Then, the resulting red-brown colloidal solution was cooled to room temperature to obtain gold colloid B.

Gold colloid C was synthesized following a modified protocol [

13]. 100 mL of HAuCl

4 solution (0.01%) was heated to boiling. Subsequently, 1 mL of 1% trisodium citrate solution was rapidly added into the boiling solution, followed by continuous magnetic stirring and heating for 15 min. The resulting colloidal solution was cooled to room temperature to obtain gold colloid C.

A silver colloid was prepared by the method of reference with a slight modification [

14]. After 100 mL of AgNO

3 solution (0.001 M) was magnetically stirred and heated to boiling, 2 mL of 1% trisodium citrate solution was rapidly introduced into the boiling solution. When the above solution changed from colorless to pale yellow, the timing began. After 60 min, the resulting colloidal solution with dark gray was cooled to room temperature to obtain silver colloid.

2.6. Raman Spectra Measurement for Samples

A certain volume of colloidal substrates (gold colloid, silver colloid), 20 μL of the prepared sample extract (as described in

Section 2.4), and a certain volume of electrolyte solution were sequentially added to the quartz bottle. The mixture was evenly placed in the Raman spectrum sampling attachment, and their Raman spectra were measured after adsorption for a certain time.

The parameters of the portable Raman spectroscopy acquisition system were set as follows: the integration time of 10 s, the laser energy of 800 mW, the average times of 2, the smoothness of 1, the spectral scanning range from 150 to 2100 cm−1, and the Raman spectra range of 400 to 1800 cm−1 used for data analysis.

2.7. Feasibility Test Scheme for SERS Detection of Sulfathiazole in Chicken Blood

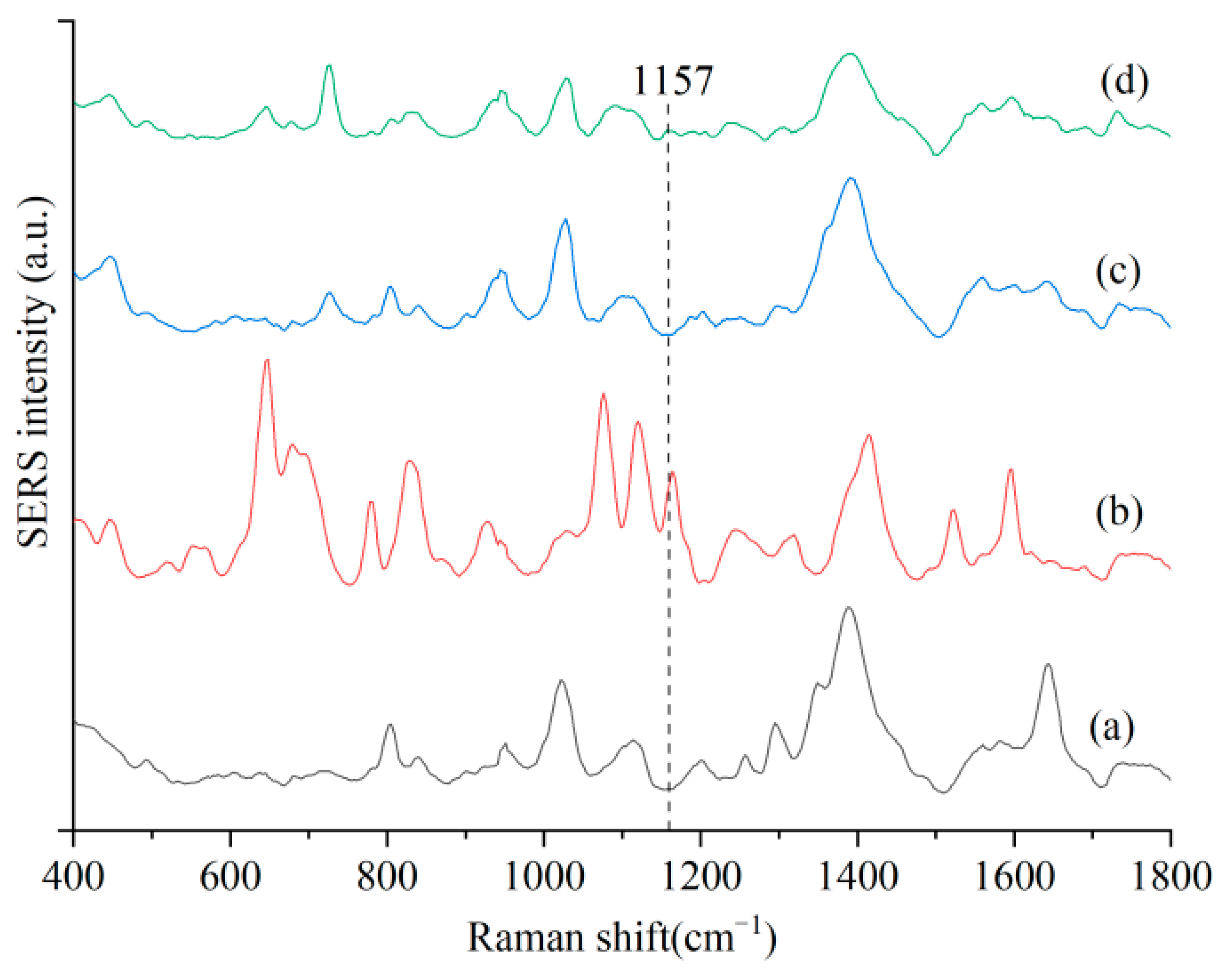

To compare the feasibility of SERS detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, the SERS spectra of the following samples were measured: gold colloid + NaCl solution, gold colloid + sulfathiazole aqueous solution (10 mg/L) + NaCl solution, gold colloid + blank chicken blood extract (without sulfathiazole) + NaCl solution, gold colloid + chicken blood extract containing sulfathiazole + NaCl solution.

2.8. Optimization Test Scheme of SERS Detection Conditions

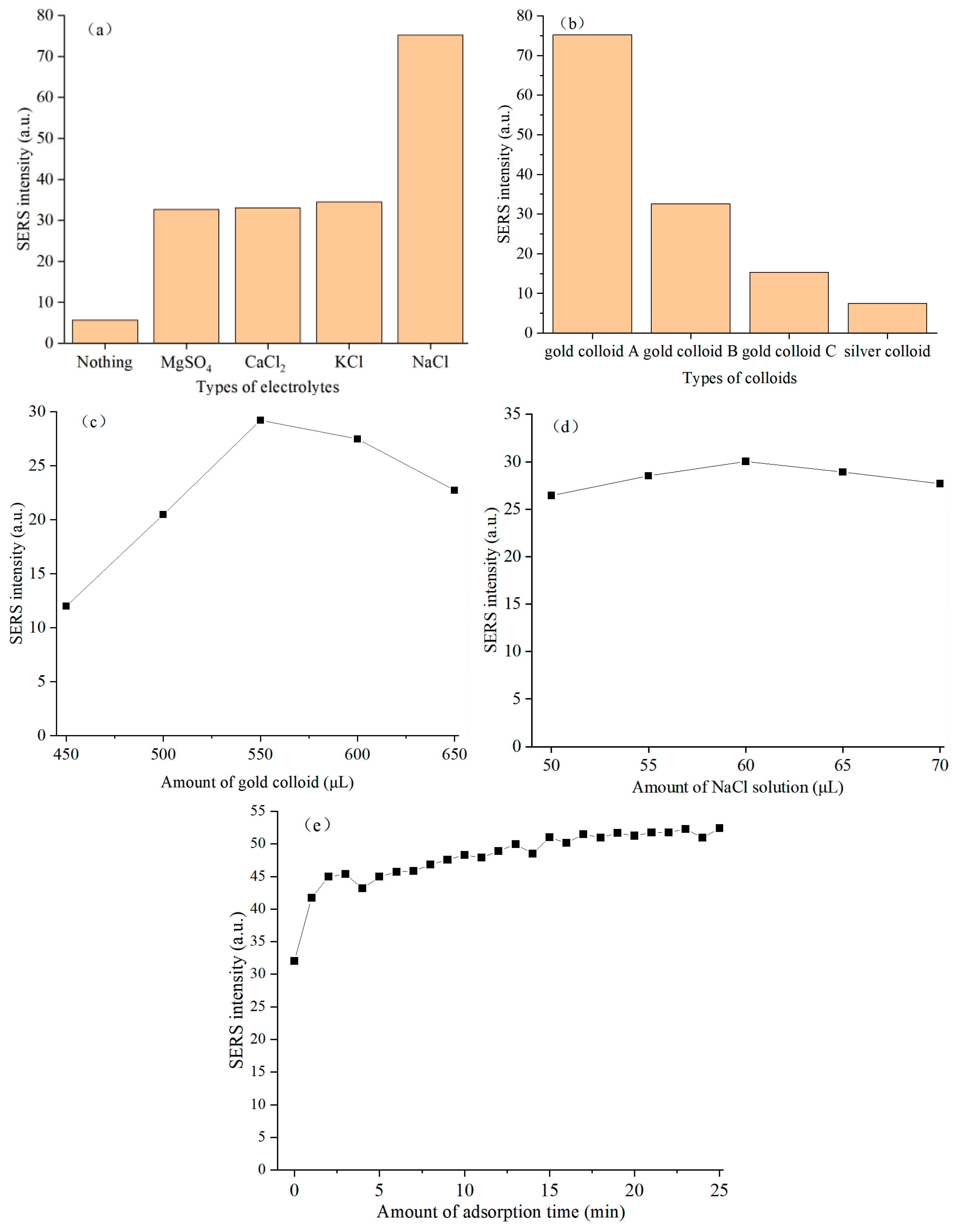

To examine the effect of different electrolytes on the SERS intensity of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, 550 μL gold colloid, 20 μL chicken blood extract containing sulfathiazole and 60 μL different kinds of electrolyte solutions (0.1 mol/L CaCl2 solution, 0.1 mol/L MgSO4 solution, 0.1 mol/L KCl solution, 0.1 mol/L NaCl solution and equal volume of ultrapure water) were added to the quartz bottle and mixed evenly. Their SERS spectra were measured after adsorption for 0 min. Five parallel samples were set under each electrolyte solution condition, and their average spectra was taken as the SERS spectra of the sample under this condition. Their SERS intensities at 1157 cm−1 were used to determine the optimal electrolyte species for detecting sulfathiazole in chicken blood sample.

To investigate the influence of different colloidal substrates on the SERS intensity of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, 550 μL different kinds of colloidal solutions (gold colloid A, gold colloid B, gold colloid C, and silver colloid) were introduced into quartz vials, followed by the addition of 20 μL chicken blood extract containing sulfathiazole and 60 μL NaCl solution (0.1 mol/L) and mixed evenly. Their SERS spectra were measured after adsorption for 0 min. Five parallel samples were set under each colloidal solution condition, and their average spectra was taken as the SERS spectra of the sample under this condition. By comparing the SERS intensities at 1157 cm−1, the optimal colloidal species were determined for the detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood samples.

To explore the effect of different amounts of gold colloid on the SERS intensity of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, different volumes (450, 500, 550, 600 and 650 μL) of gold colloid, 20 μL of chicken blood extract containing sulfathiazole and 55 μL of NaCl solution (0.1 mol/L) were added to the quartz flask and mixed evenly. Their SERS spectra were collected for 0 min. Five parallel samples were set under the condition of each gold colloid volume, and their average spectra was taken as the SERS spectra of the sample under this condition. The optimal amount of gold colloid for the detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood was determined by comparing the SERS intensities at 1157 cm−1.

To evaluate the effect of different amounts of NaCl solution on the SERS intensity of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, 550 μL gold colloid, 20 μL chicken blood extract containing sulfathiazole, and different volumes (50, 55, 60, 65 and 70 μL) of NaCl solution (0.1 mol/L) were added to the quartz flask and mixed evenly. The SERS spectra were measured for 0 min of adsorption. Five parallel samples were set under the condition of each NaCl solution volume, and their average spectra was taken as the SERS spectra of the sample under this condition. By comparing the SERS intensities at 1157 cm−1, the optimal amount of NaCl solution was determined for the detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood samples.

To determine the effect of different adsorption time on the SERS intensity of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, 550 μL gold colloid, 20 μL chicken blood extract containing sulfathiazole, and 60 μL NaCl solution (0.1 mol/L) were added to the quartz bottle and mixed evenly. The SERS spectra at different adsorption time (0 to 25 min, interval of 1 min) were measured. Five parallel samples were set up under each adsorption time condition, and their average spectra was taken as the SERS spectra of the sample under this condition. By comparing the SERS intensities at 1157 cm−1, the optimal adsorption time was determined for sulfathiazole detection in chicken blood samples.

2.9. SERS Quantitative Detection Scheme

To establish the SERS quantitative prediction model for the detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, 120 chicken blood samples containing sulfathiazole (1 to 38 mg/L) were prepared according to the procedure described in

Section 2.4. Among them, 90 samples were randomly selected as the training set samples for establishing the prediction model, and the remaining 30 samples were used as the prediction set samples. Then, under the optimal detection conditions (as determined in

Section 3.2), their SERS spectra were measured following the protocol outlined in

Section 2.6, and the SERS spectra of 400 to 1800 cm

−1 were selected to establish the prediction model.

2.10. Data Analysis Scheme

The purpose of this paper is to establish a SERS prediction model for detecting sulfathiazole in chicken blood, but its original SERS spectrum is susceptible to interference from many factors. For example, a strong broadband fluorescence background signal is generated from the chicken blood itself and the substrate, submerging the SERS characteristic peaks of the target molecule sulfathiazole. In this paper, we systematically investigated the model prediction effects of various spectral pretreatment methods and their combinations, including adaptive iterative reweighted penalized least squares (air-PLS), air-PLS combined with Savitzky–Golay smoothing (SG), air-PLS combined with first derivative, air-PLS combined with second derivative, air-PLS combined with normalization, air-PLS combined with standard normal variable transformation (SNV), air-PLS combined with multiple scattering correction (MSC). The air-PLS algorithm is implemented in Matlab R2010b, and other spectral preprocessing algorithms are implemented in Unscrambler X 10.4.

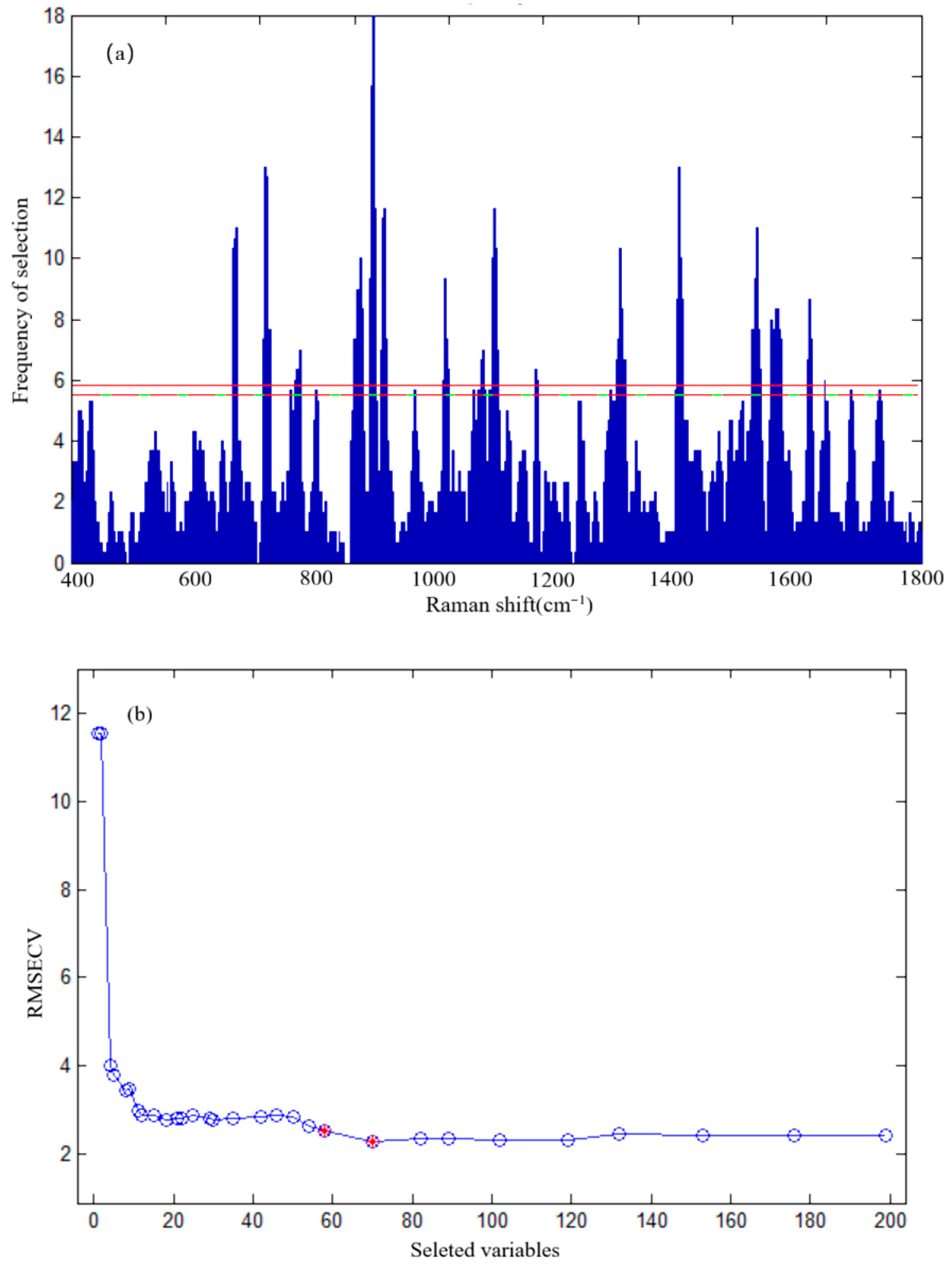

In order to screen out the characteristic variables that are most sensitive to sulfathiazole in chicken blood and most resistant to matrix interference from full-spectrum data, and to construct a more robust and more generalized quantitative analysis model, GA was used to select SERS characteristic wavelengths.

The SERS characteristic wavelengths of sulfathiazole in chicken blood were screened by Matlab GA-PLS toolkit. The relevant parameters of GA were set as follows: the initial population of 30, the mutation probability of 0.01, and the crossover probability of 0.5. The fitness function of GA was constructed by RMSECV value, and the iteration was terminated when the iteration is 100 times.

On the basis of the above characteristic wavelength selection of GA, we used SVR to establish a prediction model for sulfathiazole detection in chicken blood using Unscrambler software. The relevant parameters of SVR were set as follows: the type of SVR function of epsilon SVR, the kernel function of radial basis function (RBF), the penalty parameter C of 10, and Gamma of 0.01. In addition, two prediction models, i.e., multivariate linear regression (MLR) and partial least squares regression (PLSR), were established to objectively evaluate the prediction effect of GA-SVR model.

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimization Analysis of SERS Detection Conditions for Sulfathiazole in Chicken Blood

Although all of the four electrolyte solutions (i.e., MgSO

4, CaCl

2, KCl and NaCl) exhibited enhancement effects, there were significant differences in their enhancement magnitudes, and the order of strength was NaCl solution > KCl solution > CaCl

2 solution ≈ MgSO

4 solution. This difference was closely related to the ion type, valence state and characteristics of the electrolyte [

15,

16]. In addition, in the test sample system of chicken blood, the electrolytes might also slightly denature or precipitate the macromolecules in the tested system through the salting-out effect, reducing their non-specific adsorption on the surface of gold nanoparticles, thus indirectly providing more opportunities for sulfathiazole molecules to contact SERS hot spots. In terms of SERS detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood, NaCl was confirmed to be the optimal electrolyte type. Its excellent performance was mainly attributed to the synergistic effect of Na

+ and Cl

−, which could induce the SERS substrate to form the hot spots of the most suitable high enhancement, and effectively mitigate the interference of chicken blood matrix.

The SERS enhancement effect of gold colloid B and gold colloid C on sulfathiazole in chicken blood decreased sequentially. This trend indicated that even for gold nanocolloids, small differences in their preparation methods or physical and chemical properties, such as particle size distribution, stability and zeta potential, would greatly affect the aggregation behavior of nanoparticles in chicken blood matrix and their interaction with target molecules, eventually leading to a huge difference in enhancement efficiency [

19,

20,

21]. In addition, the SERS enhancement effect of silver colloid on sulfathiazole in chicken blood was the weakest. This might be attributed to the following primary factors. First, silver nanoparticles were prone to uncontrollable agglomeration or surface coating by biological macromolecules in the complex chicken blood matrix, resulting in the loss of plasma characteristics and the decrease in stability [

22]. Second, the chemical interaction, such as chemical adsorption, between silver colloid and the target molecule sulfathiazole was weak, and the sulfathiazole molecule could not be effectively fixed in the enhanced region [

23].

As shown from

Figure 2c, the main reason for the positive enhancement in SERS intensity of characteristic peak at this stage was as follows [

24,

25]. With the increasing of the number of gold nanoparticles, the number of SERS hot spots formed in the system increased, and the probability of effective interaction with sulfathiazole increased, thereby improving the overall enhancement efficiency. The significant downward trend was mainly due to the following two reasons [

26,

27]. Firstly, excessive gold nanoparticles were more prone to non-specific and uncontrollable agglomeration in complex chicken blood matrix to form large-sized aggregates, resulting in red shift or broadening of their local surface plasmon resonance characteristics, which reduced the enhancement factor of a single hot spot. Secondly, the high concentration of gold colloid made the laser over-scattered or absorbed when penetrating the measured system, and the generated SERS signal was re-absorbed in the path of the measured system, ultimately resulting in a decrease in the detected SERS intensity of sulfathiazole in chicken blood. In summary, more gold colloids did not necessarily result in better performance in this SERS detection system.

The positive enhancement of SERS intensity of characteristic peak with the increase in amount of NaCl solution was primarily attributed to the following reasons [

15,

16,

28]: an appropriate amount of NaCl neutralized the negative charges on the surface of gold nanoparticles, reduced the electrostatic repulsion between particles, and induced the controlled and moderate aggregation. This aggregation generated a large number of hot spots at the gaps between gold nanoparticles, thereby significantly enhancing SERS intensity of characteristic peak for sulfathiazole. The primary cause for the downward trend with the increase in amount of NaCl solution was as follows [

15,

16,

29]: excess NaCl solution further reduced the zeta potential on the surface of gold nanoparticles, further overcoming the electrostatic repulsion, leading to nonspecific and uncontrolled vigorous aggregation of gold nanoparticles and forming large-sized inactive aggregates. This process would cause redshift or broadening of their localized surface plasmon resonance properties with the enhancement factor of individual hot spots decreasing sharply. Meanwhile, large aggregates might precipitate from the system solution, further reducing surface area of the effective enhancement. Based on the above reasons, the amount of NaCl solution was a critical parameter for regulating the aggregation state of nanoparticles and optimizing the formation of hot spots in this SERS detection system.

The initial rapid increase in SERS intensity with prolonged adsorption time can be attributed to the abundance of highly active hot spots and unoccupied adsorption sites on the gold nanoparticle surfaces. During this stage, sulfathiazole molecules diffused and rapidly occupied these sites, leading to a significant SERS intensity amplification. The phenomenon of the second stage (5 to 25 min) indicated saturation of available adsorption sites on the gold nanoparticles. As equilibrium was approached, newly introduced sulfathiazole molecules faced the prolonged diffusion times to access residual sites or compete with pre-adsorbed molecules, slowing adsorption kinetics and establishing an adsorption–desorption dynamic equilibrium.

It is noteworthy that biological matrices like chicken blood were highly complex. Some factors such as the concentration of plasma proteins and the degree of hemolysis could potentially affect the aggregation behavior of gold nanoparticles and their interaction with sulfathiazole. In this study, the sample preparation step aimed to minimize such interferences by removing the majority of proteins, cellular debris and other interfering components.

Furthermore, while previous studies have primarily focused on sulfonamides detection of matrices like milk or honey [

7,

8], our work represents the first comprehensive optimization of SERS detection specifically for sulfathiazole in chicken whole blood. Its successful application in sulfathiazole detection in chicken whole blood demonstrates its potential for clinical and veterinary diagnostic applications.

4.2. Analysis of SERS Predictive Models for Sulfathiazole Detection in Chicken Blood

By comprehensive comparison of each evaluation index for spectral preprocessing, air-PLS combined with MSC emerged as the optimal preprocessing method. The resulting GA-SVR model achieved the highest fitness, lowest prediction error, and best precision and stability, confirming its ability to reflect true sulfathiazole concentration variations in chicken blood. Five replicate measurements were performed on chicken blood samples containing sulfathiazole at three concentration levels (12, 28 and 36 mg/L), with relative standard deviations ranging from 2.88% to 6.93%. The average recovery rates of spiked samples were 92.3% to 117.6%. By leveraging the characteristic peak at 1157 cm−1, this method could achieve the detection of sulfathiazole in chicken blood with a minimum concentration of 1 mg/L. In addition, future validation should include blood samples collected with different anticoagulants (e.g., EDTA) to assess the adopted method’s broad applicability.

In three models established, R2c and R2p values of SVR were the highest and most closely matched, indicating strong learning ability and optimal generalization performance, thereby effectively avoiding overfitting of SVR model. But the risk of overfitting was assessed through 10-fold cross-validation and a prediction set (30 samples). Additionally, its RMSEC and RMSEP were the lowest among all models, further confirming minimal prediction errors and high accuracy. The MLR model exhibited exceptional training set fitting (R2c value of 0.9900), but its prediction performance deteriorated markedly, with R2p dropping sharply to 0.8206 and RMSEP rising from 1.9635 to 5.0826. This substantial gap between training set and prediction set performance was a hallmark of overfitting, suggesting potential overfitting in the MLR model. The PLSR model underperformed compared to the other two models, with the lowest R2c and R2p values and the highest RMSEC and RMSEP. This indicated that while PLSR excelled in handling collinear data, its predictive capacity for sulfathiazole quantification in chicken blood was limited.