Sustainable Valorization of Crickets: Optimized Low-Pressure Supercritical CO2 Extraction and the Oil’s Properties and Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Optimization of Cricket Oil Extraction Using SC-CO2

2.2.1. Cricket Oil Extraction Using the Soxhlet Extraction Method

2.2.2. Cricket Oil Extraction Using SC-CO2

2.2.3. Experimental Design

2.3. Physicochemical Analysis of Extracted Cricket Oil Using SC-CO2

2.3.1. Determination of Acid Value and Percentage of Free Fatty Acids

2.3.2. Determination of Peroxide Value

2.3.3. Determination of Iodine Value

2.3.4. Determination of Saponification Value

2.3.5. Measurement of Cricket Oil Viscosity

2.3.6. Measurement of Cricket Oil Color

2.3.7. Determination of Oil Specific Gravity

2.3.8. Smoke Point

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

Analysis of Individual Phenolic Compounds by HPLC

2.5. Determination of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6. Determination of ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

2.7. Determination of Fatty Acids Composition

2.8. Determination of Vitamin E

2.9. Determination of Cholesterol

2.10. Determination of Oxidative Stability of Cricket Oil

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of Soxhlet-Extracted Cricket Oil

3.2. Optimization of Cricket Oil Extraction Using Supercritical CO2

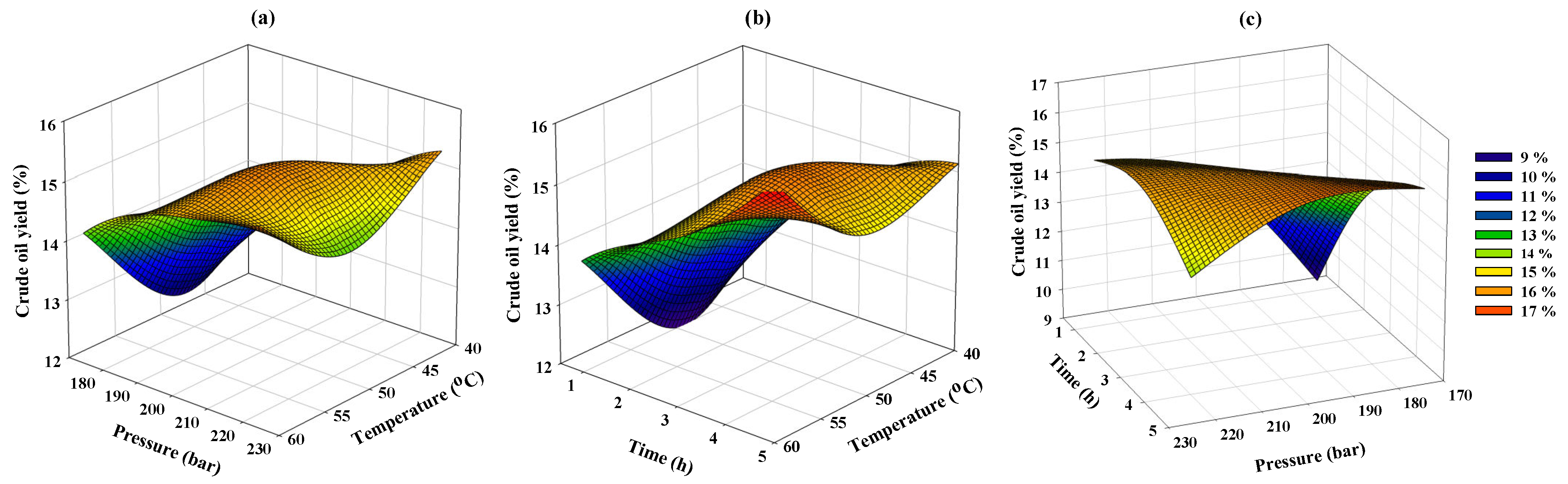

3.3. Response Surface Analysis of Cricket Oil Yield Obtained from Supercritical CO2 Extraction

3.4. Physicochemical Analysis of Extracted Cricket Oil Using Supercritical CO2

3.4.1. Acid Value and Percentage of Free Fatty Acids

3.4.2. Peroxide Value

3.4.3. Iodine Value

3.4.4. Saponification Value

3.4.5. Specific Gravity of Extracted Cricket Oil Using Supercritical CO2

3.4.6. Viscosity of Extracted Cricket Oil Using Supercritical CO2

3.4.7. Color Measurement of Extracted Cricket Oil Using Supercritical CO2

3.4.8. Smoke Point of Cricket Oil

3.5. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

3.5.1. Total Phenolic Content

3.5.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

3.5.3. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

3.6. Fatty Acids Composition

3.7. Vitamin E Content in Cricket Oil

3.8. Cholesterol Content in Cricket Oil

3.9. Optimization and Verification of Cricket Oil Extraction Process Model

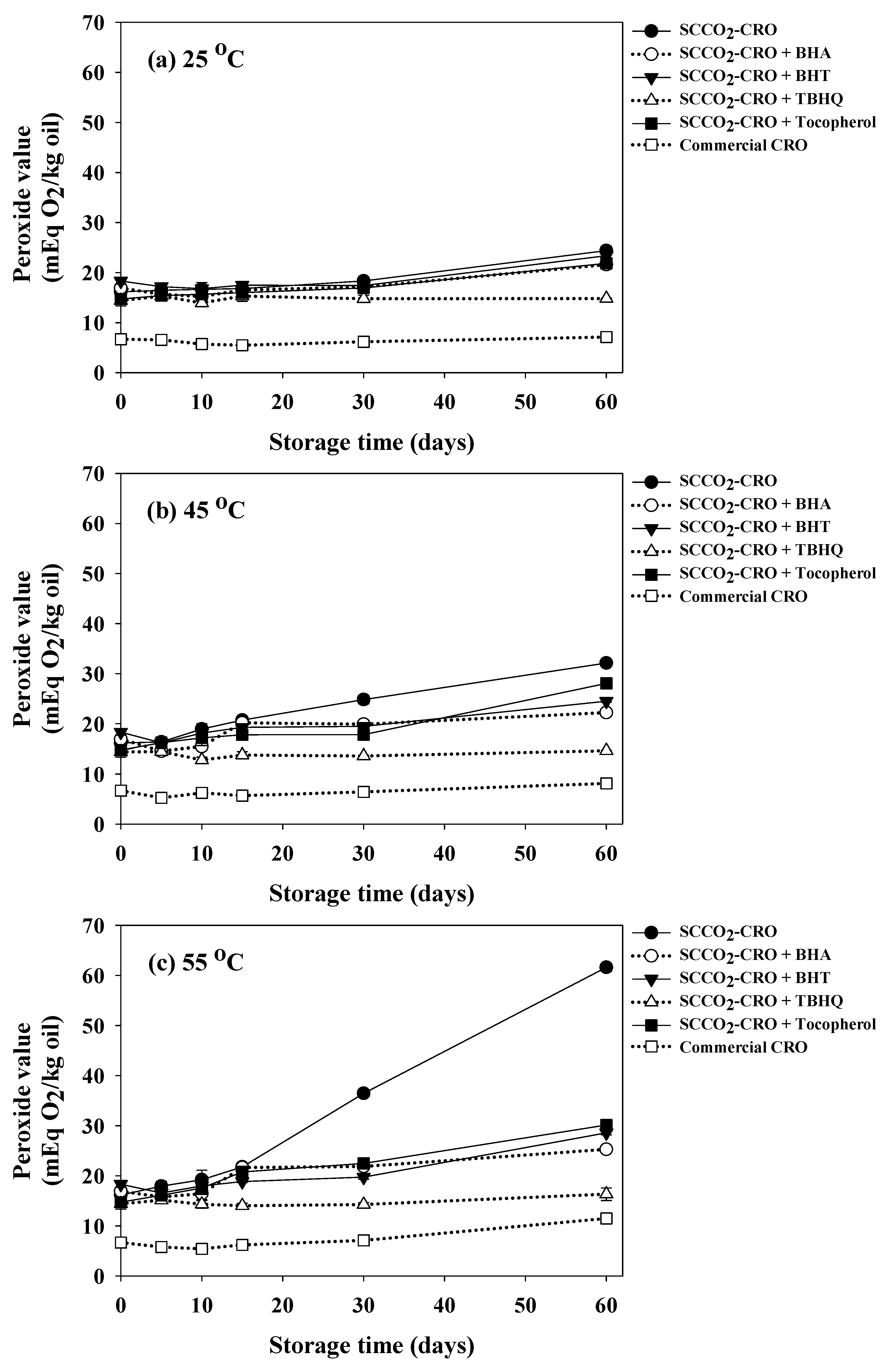

3.10. Study on Oxidative Stability of Cricket Oil

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antunes, A.L.M.; Mesquita, B.M.A.D.C.; Fonseca, F.S.A.D.; Carvalho, L.M.D.; Brandi, I.V.; Carvalho, G.G.P.D.; Coimbra, J.S.D.R. Extraction and application of lipids from edible insects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 65, 4651–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research and Markets, Global Edible Insects Market Report 2022–2030: Environmental Benefits of Edible Insects Consumption & Rising Demand for Insect Protein in the Animal Feed Industry. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2022/06/15/2462794/28124/en/Global-Edible-Insects-Market-Report-2022-2030-Environmental-Benefits-of-Edible-Insects-Consumption-Rising-Demand-for-Insect-Protein-in-the-Animal-Feed-Industry.html (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Magara, H.J.O.; Niassy, S.; Ayieko, M.A.; Mukundamago, M.; Egonyu, J.P.; Tanga, C.M.; Kimathi, E.K.; Ongere, J.O.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Hugel, S.; et al. Edible crickets (Orthoptera) around the world: Distribution, nutritional value, and other benefits—A review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, 537915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bawa, M.; Songsermpong, S.; Kaewtapee, C.; Chanput, W. Effect of diet on the growth performance, feed conversion, and nutrient content of the house cricket. J. Insect Sci. 2020, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilco-Romero, G.; Chisaguano-Tonato, A.M.; Herrera-Fontana, M.E.; Chimbo-Gándara, L.F.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M.; Vernaza, M.G.; Álvarez-Suárez, J.M. House cricket (Acheta domesticus): A review based on its nutritional composition, quality, and potential uses in the food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 142, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercola, J.; D’Adamo, C.R. Linoleic acid: A narrative review of the effects of increased intake in the standard American diet and associations with chronic disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogan, E.N.; Park, Y.-L.; Shen, C.; Matak, K.E.; Jaczynski, J. Characterization of lipids in insect powders. LWT 2023, 184, 115040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoss, K.; Glavač, N.K. Supercritical CO2 extraction vs. hexane extraction and cold pressing: Comparative analysis of seed oils from six plant species. Plants 2024, 13, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyana, W.; Inthorn, J.; Somwongin, S.; Anantaworasakul, P.; Sopharadee, S.; Yanpanya, P.; Konaka, M.; Wongwilai, W.; Dhumtanom, P.; Juntrapirom, S.; et al. The fatty acid compositions, irritation properties, and potential applications of Teleogryllus mitratus oil in nanoemulsion development. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Perreault, V.; Marciniak, A.; Gravel, A.; Chamberland, J.; Doyen, A. Comparison of conventional and sustainable lipid extraction methods for the production of oil and protein isolate from edible insect meal. Foods 2019, 8, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranil, T.; Moontree, T.; Moongngarm, A.; Loypimai, P. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of edible cricket oils from Gryllus bimaculatus and Acheta domesticus. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 6145–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugur, A.E.; Bolat, B.; Oztop, M.H.; Alpa, H. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) processing and temperature on physicochemical characterization of insect oils extracted from Acheta domesticus (house cricket) and Tenebrio molitor (yellow mealworm). Waste Biomass Valori 2021, 12, 4277–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogame, R.; Miyazawa, T.; Toda, M.; Iijima, A.; Bhaswant, M.; Miyazawa, T. Lipid composition analysis of cricket oil from crickets fed with broken rice-derived bran. Insects 2025, 16, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugu, D.K.; Onyango, A.N.; Ndiritu, A.K.; Nyangena, D.N.; Osuga, I.M.; Cheseto, X.; Subramanian, S.; Ekesi, S.; Tanga, C.M. Physicochemical properties of edible cricket oils: Implications for use in pharmaceutical and food industries. Future Foods 2024, 9, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, V.A.; Ferreira, N.J.; Cornelio-Santiago, H.P.; Santos, G.M.T.; Oliveira, A.L. Oil Extraction from black soldier fly (Hermetia Illucens L.) larvae meal by dynamic and intermittent processes of supercritical CO2—Global yield, oil characterization, and solvent consumption. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2023, 195, 105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Jung, T.S.; Ha, Y.J.; Gal, S.W.; Noh, C.W.; Kim, I.S.; Lee, J.H.; Yoo, J.H. Removal of fat from crushed black soldier fly larvae by carbon dioxide supercritical extraction. J. Anim. Feed. Sci. 2019, 28, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purschke, B.; Stegmann, T.; Schreiner, M.; Jäger, H. Pilot-scale supercritical CO2 extraction of edible insect oil from Tenebrio molitor L. Larvae—Influence of extraction conditions on kinetics, defatting performance and compositional properties. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 119, 1600134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.-K.; Kwak, B.-M.; Jang, H.W. Optimization and comparative analysis of quality characteristics and volatile profiles in edible insect oils extracted using supercritical fluid extraction and ultrasound-assisted extraction methods. Food Chem. 2025, 474, 143237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Belur, P.D.; Iyyaswami, R. Use of antioxidants for enhancing oxidative stability of bulk edible oils: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- AOCS. Official Method and Recommended Practices of the AOCS; American Oil Chemist Society: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Houshia, O.; Qutit, A. Determination of total polyphenolic antioxidants contents in west-bank olive oil. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2014, 4, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyczkowska, J.; Kozłowska, M. Effect of oils extracted from plant seeds on the growth and lipolytic activity of Yarrowia lipolytica Yeast. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mattia, C.; Battista, N.; Sacchetti, G.; Serafini, M. Antioxidant activities in vitro of water and liposoluble extracts obtained by different species of edible insects and invertebrates. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G.H.S. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, W.R.; Smith, L.M. Preparation of fatty acid methyl esters and dimethylacetals from lipids with boron fluoride–methanol. J. Lipid Res. 1964, 5, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVries, J.W.; Klipberg, D.C.; Ivroff, J.C. Concurrent Analysis of Vitamin A and Vitamin E. In Liquid Chromatographic Analysis of Food and Beverages; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hasani, S.M.; Hlavac, J.; Carpenter, M.W. Rapid determination of cholesterol in single and multicomponent prepared foods. J. AOAC Int. 1993, 76, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leila, M.; Ratiba, D.; Al-Marzouqi, A.-H. Experimental and mathematical modelling data of green process of essential oil extraction: Supercritical CO2 extraction. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-K.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, W.-J.; Hee, Y.-Y.; Zainal Abedin, N.H.; Abas, F.; Chong, G.-H. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of pomegranate peel-seed mixture: Yield and modelling. J. Food Eng. 2021, 301, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Han, S.; Jiao, Z.; Cheng, J.; Song, J. Antioxidant activity and total polyphenols content of camellia oil extracted by optimized supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2019, 96, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Shi, L.; Wu, J.; Hu, S.; Shang, Y.; Hassan, M.; Zhao, C.; Gu, Y.; Shi, L.; Wu, J.; et al. Quantitative prediction of acid value of camellia seed oil based on hyperspectral imaging technology fusing spectral and image features. Foods 2024, 13, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapuzzi, C.; Chwojnik, T.; Verotta, L.; Beretta, G.; Navarini, L.; Lupinelli, S.; Marzorati, S. Supercritical CO2 extraction of lipids from coffee silverskin: From laboratory optimization to industrial scale-up. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 45, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, N.T.; Temelli, F. Extraction conditions and moisture content of canola flakes as related to lipid composition of supercritical CO2 extracts. J. Food Sci. 1997, 62, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Matsakas, L.; Sartaj, K.; Chandra, R. In Green Sustainable Process for Chemical and Environmental Engineering and Science; Asiri, A.M.I., Isloor, A.M., Eds.; Chapter 2—Extraction of lipids from algae using supercritical carbon dioxide. Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 17–39. ISBN 978-0-12-817388-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission, Standard for Named Vegetable Oils (CXS 210-1999). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B210-1999%252FCXS_210e.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Wen, S.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Sagymbek, A.; Yu, X. Analytical methods for determining the peroxide value of edible oils: A mini-review. Food Chem. 2021, 358, 129834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pothinam, S.; Siriwoharn, T.; Jirarattanarangsri, W. Optimization of perilla seed oil extraction using supercritical CO2. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2025, 17, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Ikeya, Y.; Adachi, S.; Yagasaki, K.; Nihei, K.; Itoh, N. Extraction of strawberry leaves with supercritical carbon dioxide and entrainers: Antioxidant capacity, total phenolic content, and inhibitory effect on uric acid production of the extract. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 117, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulassery, S.; Abraham, B.; Ajikumar, N.; Munnilath, A.; Yoosaf, K. Rapid iodine value estimation using a handheld Raman spectrometer for on-site, reagent-free authentication of edible oils. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 9164–9171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, U.; Rodríguez-Seoane, P.; Díaz-Reinoso, B.; Domínguez, H. Extraction of fatty acids and phenolics from Mastocarpus stellatus using pressurized green solvents. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiriyacharee, P.; Chalermchat, Y.; Siriwoharn, T.; Jirarattanarangsri, W.; Tangjaidee, P.; Chaipoot, S.; Phongphisutthinant, R.; Pandith, H.; Muangrat, R. Utilizing supercritical CO2 for bee brood oil extraction and analysis of its chemical properties. Foods 2024, 13, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.; Hanganu, A.; Dumitriu, R.; Tociu, M.; Ivanov, G.; Stavarache, C.; Popescu, L.; Ghendov-Mosanu, A.; Sturza, R.; Deleanu, C.; et al. Saponification value of fats and oils as determined from 1H-NMR data: The case of dairy fats. Foods 2022, 11, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, J.G.; Okonkwo, P.C.; Mukhtar, B.; Baba, A. Influence of extraction temperature on the quality of neem seed oil: Preliminary investigation. ABUAD J. Eng. Res. Dev. 2024, 7, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngampeerapong, C.; Nakprasom, K.; Wangcharoen, W.; Rahong, N.; Changpradit, T.; Waseeanuruk, T.; Tangsuphoom, N. Effect of extraction methods on fatty acid composition, and chemical and physical characteristics of oil from house crickets (Acheta domesticus). J. Food Technol. Siam Univ. 2024, 19, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Muangrat, R.; Kaikonjanat, A. Comparative evaluation of hemp seed oil yield and physicochemical properties using supercritical CO2, accelerated hexane, and screw press extraction techniques. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temelli, F. Extraction of triglycerides and phospholipids from canola with supercritical carbon dioxide and ethanol. J. Food Sci. 1992, 57, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, D.N.; Lee, S.H.; Yoo, S.-H.; Lee, S. Correlation of fatty acid composition of vegetable oils with rheological behaviour and oil uptake. Food Chem. 2010, 118, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wu, G.; Li, P.; Qi, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Jin, Q. The effect of fatty acid composition on the oil absorption behavior and surface morphology of fried potato sticks via LF-NMR, MRI, and SEM. Food Chem. X 2020, 7, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwineza, P.A.; Waśkiewicz, A. Recent advances in supercritical fluid extraction of natural bioactive compounds from natural plant materials. Molecules 2020, 25, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Kumar, M.; Dwivedi, P.; Shinde, L.P. Functional and nutritional health benefit of cold-pressed oils: A review. J. Agric. Ecol. 2020, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvy, V.; Fidgett, A.L.; Preziosi, R.F. Differences in carotenoid accumulation among three feeder-cricket species: Implications for carotenoid delivery to captive insectivores. Zoo Biol. 2012, 31, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, P.; Chatterjee, M.; Bhattacharjya, A.; Lahiri, S. Smoke points: A crucial factor in cooking oil selection for public health. Curr. Funct. Foods 2024, 2, E041223224179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazina, N.; He, J. Analysis of fatty acid profiles of free fatty acids generated in deep-frying process. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3085–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, S.; Kumar, M.; Siroha, A.K.; Purewal, S.S. Rice bran oil: Emerging trends in extraction, health benefit, and its industrial application. Rice Sci. 2021, 28, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A. A comprehensive review on different classes of polyphenolic compounds present in edible oils. Food Res. Int. Ott. Ont. 2021, 143, 110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pineda, M.; Juan, T.; Antoniewska-Krzeska, A.; Vercet, A.; Abenoza, M.; Yagüe-Ruiz, C.; Rutkowska, J. Exploring the potential of yellow mealworm (Tenebrio Molitor) oil as a nutraceutical ingredient. Foods 2024, 13, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimić, I.; Pavlić, B.; Rakita, S.; Cvetanović Kljakić, A.; Zeković, Z.; Teslić, N. Isolation of cherry seed oil using conventional techniques and supercritical fluid extraction. Foods 2023, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćurko, N.; Lukić, K.; Tušek, A.J.; Balbino, S.; Vukušić Pavičić, T.; Tomašević, M.; Redovniković, I.R.; Ganić, K.K. Effect of cold pressing and supercritical CO2 extraction assisted with pulsed electric fields pretreatment on grape seed oil yield, composition and antioxidant characteristics. LWT 2023, 184, 114974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonmee, N.; Chittrakorn, S.; Detyothin, S.; Tochampa, W.; Sriphannam, C.; Ruttarattanamongkol, K. Effects of high pressure and ultrasonication pretreatments and supercritical carbon dioxide extraction on physico-chemical properties of edible insect oils. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shramko, V.S.; Polonskaya, Y.V.; Kashtanova, E.V.; Stakhneva, E.M.; Ragino, Y.I. The short overview on the relevance of fatty acids for human cardiovascular disorders. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; He, H. The role of linoleic acid in skin and hair health: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonarsa, P.; Bunyatratchata, A.; Phuseerit, O.; Phonphan, N.; Chumroenphat, T.; Dechakhamphu, A.; Thammapat, P.; Katisart, T.; Siriamornpun, S. Quality variation of house cricket (Acheta domesticus) powder from thai farms: Chemical composition, micronutrients, bioactive compounds, and microbiological safety. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, V.A.; Vicentini-Polette, C.M.; Magalhaes, D.R.; de Oliveira, A.L. Extraction, characterization, and use of edible insect oil—A review. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USA. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service FoodData Central: Fat, Beef Tallow (SR LEGACY, 171400). Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/171400/nutrients (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- USA. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service FoodData Central: Lard (SR LEGACY, 171401). Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/171401/nutrients (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Cao, Y.; Yu, Y. Associations between cholesterol intake, food sources and cardiovascular disease in chinese residents. Nutrients 2024, 16, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zio, S.; Tarnagda, B.; Tapsoba, F.; Zongo, C.; Savadogo, A. Health interest of cholesterol and phytosterols and their contribution to one health approach: Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzompa-Sosa, D.A.; Dewettinck, K.; Provijn, P.; Brouwers, J.F.; de Meulenaer, B.; Oonincx, D.G.A.B. Lipidome of cricket species used as food. Food Chem. 2021, 349, 129077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USA. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service FoodData Central: Oil, Vegetable, Soybean, Refined (SR LEGACY, 172370). Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/172370/nutrients (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration; Ministry of Public Health. Annex 3 to Notification of the Ministry of Public Health (No. 445) B.E. 2566 (2023) Issued by the Virtue of Food Act B.E. 2522 (1979), Re: Nutrition Labelling. 2023. Available online: https://food.fda.moph.go.th/media.php?id=689363893683888128&name=P445_EN.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- USA Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025, 9th ed.; U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Leonardis, A.D.; Cuomo, F.; Macciola, V.; Lopez, F. Influence of free fatty acid content on the oxidative stability of red palm oil. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 101098–101104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaino, M.; Sano, T.; Kato, S.; Shimizu, N.; Ito, J.; Rahmania, H.; Imagi, J.; Nakagawa, K. Carboxylic acids derived from triacylglycerols that contribute to the increase in acid value during the thermal oxidation of oils. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinkhani, M.; Farhoosh, R. Kinetics of chemical deteriorations over the frying protected by gallic acid and methyl gallate. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Meng, F.; Wang, B.; Cao, Y. Effects of antioxidants on physicochemical properties and odorants in heat processed beef flavor and their antioxidant activity under different storage conditions. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 966697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | Uncoded Independent Variables | Coded Independent Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (X1, °C) | Pressure (X2, bar) | Time (X3, h) | Temperature | Pressure | Time | |

| 1 | 40 | 175 | 3 | −1 | −1 | 0 |

| 2 | 60 | 175 | 3 | 1 | −1 | 0 |

| 3 | 40 | 225 | 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 60 | 225 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | 40 | 200 | 1 | −1 | 0 | −1 |

| 6 | 60 | 200 | 1 | 1 | 0 | −1 |

| 7 | 40 | 200 | 5 | −1 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | 60 | 200 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 9 | 50 | 175 | 1 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| 10 | 50 | 225 | 1 | 0 | 1 | −1 |

| 11 | 50 | 175 | 5 | 0 | −1 | 1 |

| 12 | 50 | 225 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | 50 | 200 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 50 | 200 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 50 | 200 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Physical and Chemical Properties | Cricket Oil Extracted by Soxhlet Extraction Method |

|---|---|

| % oil yield | 15.75 ± 1.07 |

| Acid value (mg KOH/g oil) | 11.54 ± 0.15 |

| Peroxide value (mEq O2/kg oil) | 40.04 ± 2.57 |

| Iodine value (g I2/100 g oil) | 68.75 ± 2.09 |

| Saponification value (mg KOH/g oil) | 168.41 ± 2.63 |

| Viscosity (cP) | 64.18 ± 0.41 |

| Density (g/cm3) | 0.901 ± 0.001 |

| Extraction Conditions | Crude Oil Yield (%) | Defatted Cricket Meal (%) | Total Mass Balance (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (X1, °C) | Pressure (X2, bar) | Time (X3, h) | |||

| 40 | 175 | 3 | 13.58 ± 0.00 ef | 87.17 ± 0.95 abc | 100.75 ± 0.95 bcde |

| 60 | 175 | 3 | 14.24 ± 0.01 cde | 84.79 ± 0.52 ef | 99.02 ± 0.52 f |

| 40 | 225 | 3 | 15.21 ± 0.34 b | 86.24 ± 0.06 cd | 101.45 ± 0.39 ab |

| 60 | 225 | 3 | 15.34 ± 0.41 ab | 84.35 ± 0.91 fg | 99.70 ± 0.50 ef |

| 40 | 200 | 1 | 13.28 ± 1.19 f | 87.69 ± 0.06 a | 100.96 ± 1.13 bcd |

| 60 | 200 | 1 | 13.87 ± 0.67 def | 86.44 ± 0.69 bcd | 100.31 ± 0.03 cde |

| 40 | 200 | 5 | 15.14 ± 0.00 bc | 85.79 ± 0.00 de | 100.93 ± 0.00 bcd |

| 60 | 200 | 5 | 16.19 ± 0.28 a | 84.94 ± 0.04 ef | 101.13 ± 0.25 abc |

| 50 | 175 | 1 | 9.35 ± 0.00 g | 87.15 ± 0.00 abc | 96.50 ± 0.00 h |

| 50 | 225 | 1 | 14.66 ± 0.00 bcd | 87.39 ± 0.00 ab | 102.05 ± 0.00 a |

| 50 | 175 | 5 | 15.54 ± 0.19 ab | 83.66 ± 0.17 g | 99.20 ± 0.03 f |

| 50 | 225 | 5 | 13.83 ± 0.00 def | 84.01 ± 0.00 fg | 97.84 ± 0.00 g |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 15.42 ± 0.23 ab | 85.06 ± 0.66 ef | 100.48 ± 0.43 bcde |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 15.01 ± 0.10 bc | 84.91 ± 0.36 ef | 99.92 ± 0.26 def |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 15.12 ± 0.35 bc | 84.89 ± 0.04 ef | 100.01 ± 0.31 def |

| Source | DF | Seq SS | Adj SS | Adj MS | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 7 | 72.243 | 72.243 | 10.321 | 63.440 | 0.000 |

| Linear | 3 | 34.296 | 34.296 | 11.432 | 70.280 | 0.000 |

| Temperature | 1 | 1.479 | 1.479 | 1.479 | 9.090 | 0.006 |

| Pressure | 1 | 10.042 | 10.042 | 10.042 | 61.730 | 0.000 |

| Time | 1 | 22.775 | 22.775 | 22.775 | 140.000 | 0.000 |

| Square | 3 | 13.299 | 13.299 | 4.433 | 27.250 | 0.000 |

| Temperature × Temperature | 1 | 1.673 | 0.863 | 0.863 | 5.310 | 0.031 |

| Pressure × Pressure | 1 | 5.541 | 6.435 | 6.435 | 39.560 | 0.000 |

| Time × Time | 1 | 6.084 | 6.084 | 6.084 | 37.400 | 0.000 |

| Interaction | 1 | 24.649 | 24.649 | 24.649 | 151.520 | 0.000 |

| Pressure × Time | 1 | 24.649 | 24.649 | 24.649 | 151.520 | 0.000 |

| Residual Error | 22 | 3.579 | 3.579 | 0.163 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 5 | 0.959 | 0.959 | 0.192 | 1.240 | 0.332 |

| Pure Error | 17 | 2.620 | 2.620 | 0.154 | ||

| Total | 29 | 75.822 |

| Temperature (°C) | Pressure (bar) | Time (h) | Acid Value (mg KOH/g Oil) | Peroxide Value (mEq O2/kg Oil) | Iodine Value ns (g I2/100 g Oil) | Saponification Value (mg KOH/g Oil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 175 | 3 | 4.76 ± 0.96 ab | 20.06 ± 1.83 j | 74.80 ± 2.32 | 178.07 ± 8.33 c |

| 60 | 175 | 3 | 3.71 ± 0.18 cde | 25.42 ± 0.03 i | 71.06 ± 5.53 | 196.76 ± 8.80 a |

| 40 | 225 | 3 | 2.97 ± 0.39 defg | 38.87 ± 1.11 g | 76.20 ± 1.02 | 189.10 ± 8.60 abc |

| 60 | 225 | 3 | 3.39 ± 0.17 cdef | 67.82 ± 0.09 a | 75.33 ± 1.31 | 193.90 ± 6.73 ab |

| 40 | 200 | 1 | 3.98 ± 0.21 bc | 32.88 ± 1.10 h | 76.19 ± 1.43 | 191.59 ± 4.48 abc |

| 60 | 200 | 1 | 5.14 ± 0.80 a | 23.36 ± 1.57 i | 72.68 ± 4.33 | 191.05 ± 7.24 abc |

| 40 | 200 | 5 | 3.18 ± 0.06 cdefg | 50.94 ± 1.78 d | 70.59 ± 5.02 | 182.31 ± 0.12 bc |

| 60 | 200 | 5 | 2.91 ± 0.32 efg | 47.29 ± 0.39 e | 75.62 ± 0.62 | 186.46 ± 1.45 abc |

| 50 | 175 | 1 | 4.79 ± 0.03 ab | 44.03 ± 0.80 f | 70.94 ± 4.41 | 181.98 ± 8.21 bc |

| 50 | 225 | 1 | 2.45 ± 0.05 g | 70.34 ± 0.82 a | 75.01 ± 3.51 | 188.97 ± 0.21 abc |

| 50 | 175 | 5 | 3.25 ± 0.08 cdefg | 32.35 ± 0.58 h | 75.46 ± 0.26 | 190.39 ± 3.85 abc |

| 50 | 225 | 5 | 2.76 ± 0.03 fg | 38.76 ± 1.60 g | 77.15 ± 0.40 | 183.74 ± 3.91 abc |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 3.33 ± 0.23 cdef | 56.61 ± 1.29 c | 75.40 ± 1.57 | 192.93 ± 3.52 ab |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 3.82 ± 0.29 cd | 57.61 ± 0.72 c | 74.96 ± 1.48 | 191.10 ± 3.04 abc |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 3.54 ± 0.27 cdef | 63.94 ± 4.02 b | 73.80 ± 1.24 | 184.57 ± 3.59 abc |

| Screw-pressed commercial cricket oil | 5.17 ± 0.03 a | 8.22 ± 0.41 k | 72.99 ± 5.99 | 190.79 ± 5.15 abc | ||

| Temperature (°C) | Pressure (bar) | Time (h) | Specific Gravity | Viscosity (cP) | Color Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | |||||

| 40 | 175 | 3 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 109.45 ± 0.35 bc | 56.99 ± 0.28 ij | 11.49 ± 0.03 i | 90.43 ± 0.38 kl |

| 60 | 175 | 3 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 101.80 ± 0.57 de | 65.71 ± 1.06 f | 11.22 ± 0.13 j | 104.93 ± 1.39 g |

| 40 | 225 | 3 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 132.35 ± 5.30 a | 70.51 ± 2.14 e | 13.75 ± 0.37 e | 113.39 ± 3.09 e |

| 60 | 225 | 3 | 0.92 ± 0.00 ab | 101.00 ± 0.57 e | 61.58 ± 0.52 g | 14.57 ± 0.08 d | 100.77 ± 0.66 h |

| 40 | 200 | 1 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 81.81 ± 1.38 hi | 72.85 ± 1.29 d | 12.25 ± 0.21 g | 116.25 ± 1.76 d |

| 60 | 200 | 1 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 91.81 ± 0.59 g | 57.69 ± 1.09 i | 10.49 ± 0.02 k | 93.35 ± 1.57 j |

| 40 | 200 | 5 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 77.36 ± 1.37 j | 78.32 ± 0.11 b | 9.55 ± 0.05 l | 122.48 ± 0.23 b |

| 60 | 200 | 5 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 83.89 ± 1.17 h | 81.34 ± 0.76 a | 8.00 ± 0.19 m | 124.96 ± 1.05 a |

| 50 | 175 | 1 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 97.07 ± 0.62 f | 66.28 ± 0.22 f | 11.69 ± 0.06 hi | 106.17 ± 0.37 fg |

| 50 | 225 | 1 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 92.08 ± 1.77 g | 55.86 ± 0.47 j | 13.29 ± 0.02 f | 91.71 ± 0.70 jk |

| 50 | 175 | 5 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 81.81 ± 1.38 hi | 75.85 ± 1.54 c | 11.75 ± 0.23 h | 120.15 ± 2.13 c |

| 50 | 225 | 5 | 0.92 ± 0.00 a | 105.00 ± 0.42 d | 66.14 ± 0.43 f | 16.39 ± 0.08 b | 107.86 ± 0.55 f |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 109.85 ± 0.21 bc | 59.93 ± 0.75 h | 16.17 ± 0.06 bc | 98.36 ± 1.16 i |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 0.91 ± 0.00 b | 108.75 ± 0.64 c | 53.68 ± 0.09 k | 14.78 ± 0.01 d | 88.75 ± 0.13 l |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 0.92 ± 0.00 ab | 112.50 ± 0.85 b | 60.03 ± 0.33 h | 15.97 ± 0.01 c | 98.76 ± 0.38 hi |

| Screw-pressed commercial cricket oil | 0.92 ± 0.00 a | 78.34 ± 0.39 ij | 74.74 ± 0.10 c | 16.85 ± 0.06 a | 112.80 ± 0.13 e | ||

| Temperature (°C) | Pressure (bar) | Time (h) | Smoke Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 200 | 5 | 144.00 ± 4.24 c |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 150.00 ± 4.24 b |

| Screw-pressed commercial cricket oil | 130.00 ± 2.83 d | ||

| Rice bran oil | 216.00 ± 1.42 a | ||

| Temperature (°C) | Pressure (bar) | Time (h) | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/kg Oil) | DPPH (mg Eq Trolox/kg Oil) | ABTS (mg Eq Trolox/kg Oil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 175 | 3 | 50.73 ± 0.47 b | 3.29 ± 0.11 k | 106.17 ± 4.14 cde |

| 60 | 175 | 3 | 27.17 ± 1.14 ef | 18.68 ± 0.06 gh | 103.88 ± 5.40 de |

| 40 | 225 | 3 | 25.71 ± 1.00 fg | 19.10 ± 0.05 gh | 111.67 ± 1.20 cd |

| 60 | 225 | 3 | 25.67 ± 1.55 fg | 17.52 ± 0.14 i | 124.57 ± 2.96 b |

| 40 | 200 | 1 | 20.83 ± 0.84 ij | 10.32 ± 1.73 j | 145.90 ± 7.77 a |

| 60 | 200 | 1 | 37.17 ± 0.68 c | 23.32 ± 0.38 f | 36.82 ± 1.97 i |

| 40 | 200 | 5 | 20.81 ± 1.45 ij | 47.58 ± 0.91 b | 120.84 ± 1.95 b |

| 60 | 200 | 5 | 21.18 ± 1.02 ij | 49.97 ± 0.56 a | 100.56 ± 1.98 e |

| 50 | 175 | 1 | 33.44 ± 1.63 d | 32.35 ± 1.82 d | 48.97 ± 1.70 h |

| 50 | 225 | 1 | 19.56 ± 0.58 k | 9.39 ± 1.52 j | 65.07 ± 0.23 f |

| 50 | 175 | 5 | 21.76 ± 0.29 i | 26.39 ± 0.08 e | 112.93 ± 2.64 c |

| 50 | 225 | 5 | 24.19 ± 0.67 gh | 31.66 ± 1.29 d | 125.85 ± 1.87 b |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 24.59 ± 0.51 gh | 18.32 ± 0.65 i | 59.48 ± 1.73 fg |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 22.75 ± 0.50 hi | 18.26 ± 0.54 i | 56.04 ± 1.27 gh |

| 50 | 200 | 3 | 28.04 ± 0.34 e | 20.43 ± 0.86 g | 63.13 ± 1.73 fg |

| Screw-pressed commercial cricket oil | 91.41 ± 0.80 a | 42.35 ± 0.59 c | 139.59 ± 6.86 a | ||

| Samples | Phenolic Compounds | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Dried cricket | Gallic acid (µg/g) | 1.30 ± 0.07 |

| Myricetin (µg/g) | 2.64 ± 0.36 | |

| Defatted cricket from supercritical CO2 extraction (50 °C, 200 bar, 3 h) | Gallic acid (µg/g) | 0.56 ± 0.00 |

| Myricetin (µg/g) | 0.93 ± 0.01 | |

| Defatted cricket from supercritical CO2 extraction (60 °C, 175 bar, 5 h) | Gallic acid (µg/g) | 0.35 ± 0.09 |

| Myricetin (µg/g) | 1.72 ± 0.08 | |

| Cricket oil from supercritical CO2 extraction (50 °C, 200 bar, 3 h) | Gallic acid (µg/mL) | 2.55 ± 0.02 |

| Cricket oil from supercritical CO2 extraction (60 °C, 175 bar, 5 h) | Gallic acid (µg/mL) | 2.50 ± 0.05 |

| Cricket oil from supercritical CO2 extraction (60 °C, 200 bar, 5 h) | Gallic acid (µg/mL) | 4.69 ± 0.20 |

| Screw-pressed commercial cricket oil | Gallic acid (µg/mL) | 3.51 ± 0.12 |

| Myricetin (µg/mL) | 28.62 ± 4.12 | |

| Trans-cinnamic acid (µg/mL) | 1.04 ± 0.24 |

| Fatty Acid Composition (%) | SC-CO2 Extraction Condition | Screw-Pressed Commercial Cricket Oil | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 °C 175 bar 3 h | 40 °C 200 bar 5 h | 40 °C 225 bar 3 h | 50 °C 175 bar 5 h | 50 °C 200 bar 3 h | 50 °C 225 bar 5 h | 60 °C 175 bar 3 h | 60 °C 200 bar 5 h | 60 °C 225 bar 3 h | ||

| Lauric acid (C12:0) | 0.11 ± 0.01 ab | 0.12 ± 0.00 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 abc | 0.11 ± 0.01 ab | 0.09 ± 0.01 cd | 0.11 ± 0.00 ab | 0.10 ± 0.00 bcd | nd | 0.09 ± 0.00 d | nd |

| Myristic acid (C14:0) | 0.57 ± 0.01 cd | 0.53 ± 0.00 e | 0.61 ± 0.01 ab | 0.56 ± 0.00 de | 0.54 ± 0.02 e | 0.54 ± 0.00 e | 0.59 ± 0.00 bcd | 0.54 ± 0.01 e | 0.62 ± 0.00 a | 0.59 ± 0.03 abc |

| Pentadecylic acid (C15:0) | 0.09 ± 0.01 bc | 0.10 ± 0.00 bc | 0.13± 0.03 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 b | 0.09 ± 0.00 bc | 0.10 ± 0.00 bc | 0.09 ± 0.00 bc | 0.09 ± 0.01 bc | 0.08 ± 0.00 c | 0.06 ± 0.00 d |

| Palmitic acid (C16:0) | 27.84 ± 0.01 cd | 27.81 ± 0.02 cd | 27.87 ± 0.05 c | 27.91 ± 0.01 c | 28.84 ± 0.01 a | 27.36 ± 0.00 d | 28.27 ± 0.03 bc | 28.50 ± 0.11 ab | 28.31 ± 0.02 bc | 28.30 ± 0.05 bc |

| Palmitoleic acid (C16:1) | 0.72 ± 0.05 de | 0.67 ± 0.00 ef | 0.99 ± 0.03 a | 0.63 ± 0.01 f | 0.67 ± 0.00 ef | 0.66 ± 0.00 f | 0.75 ± 0.00 cd | 0.74 ± 0.00 cd | 0.78 ± 0.00 bc | 0.81 ± 0.03 b |

| Margaric acid (C17:0) | 0.26 ± 0.03 abc | 0.29 ± 0.00 abc | 0.31 ± 0.00 a | 0.29 ± 0.00 ab | 0.28 ± 0.00 abc | 0.27 ± 0.00 bcd | 0.24 ± 0.00 de | 0.26 ± 0.01 cd | 0.22 ± 0.00 e | 0.16 ± 0.03 f |

| Stearic acid (C18:0) | 6.95 ± 0.42 de | 6.81 ± 0.02 e | 7.09 ± 0.04 de | 7.50 ± 0.00 c | 8.10 ± 0.01 b | 6.99 ± 0.00 de | 7.26 ± 0.02 cd | 8.17 ± 0.0 b | 8.11 ± 0.03 b | 8.53 ± 0.01 a |

| Elaidic acid (C18:1 n9t) | nd | nd | 2.00 ± 0.07 a | 0.92 ± 0.00 c | 0.83 ± 0.01 d | nd | nd | 1.13 ± 0.01 b | nd | 0.72 ± 0.07 e |

| Oleic acid (C18:1 n9c) | 28.22 ± 0.78 c | 27.16 ± 0.06 ef | 25.00 ± 0.01 g | 27.31 ± 0.00 def | 27.68 ± 0.03 cde | 27.83 ± 0.03 cd | 28.84 ± 0.08 b | 26.82 ± 0.03 f | 30.23 ± 0.03 a | 28.79 ± 0.03 b |

| Linoelaidic acid (C18:2 n6t) | nd | nd | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.09 ± 0.00 b | 0.08 ± 0.00 c | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Linoleic acid (C18:2 n6c) | 33.68 ± 1.88 a | 34.96 ± 0.00 a | 27.02 ± 0.01 e | 32.04 ± 0.00 b | 30.48 ± 0.02 c | 34.55 ± 0.01 a | 32.31 ± 0.06 b | 28.38 ± 0.04 d | 30.07 ± 0.01 c | 30.05 ± 0.06 c |

| Arachidic acid (C20:0) | 0.26 ± 0.03 c | 0.30 ± 0.00 b | 0.31 ± 0.02 b | 0.34 ± 0.00 a | 0.34 ± 0.00 a | 0.30 ± 0.01 b | 0.24 ± 0.00 c | 0.31 ± 0.01 b | 0.24 ± 0.00 c | 0.24 ± 0.00 c |

| γ-Linolenic acid (C18:3 n6) | nd | nd | 0.50 ± 0.00 a | 0.07 ± 0.01 c | 0.06 ± 0.00 d | nd | nd | 0.24 ± 0.00 b | nd | 0.06 ± 0.00 d |

| Gondoic acid (C20:1) | nd | nd | nd | 0.05 ± 0.01 b | 0.05 ± 0.00 b | nd | nd | 0.09 ± 0.02 a | nd | 0.03 ± 0.00 c |

| α-Linolenic acid (C18:3 n3) | 0.63 ± 0.05 bc | 0.58 ± 0.01 d | 0.41 ± 0.01 f | 0.52 ± 0.02 e | 0.52 ± 0.00 e | 0.60 ± 0.01 cd | 0.67 ± 0.01 ab | 0.64 ± 0.00 bc | 0.69 ± 0.00 a | 0.49 ± 0.02 e |

| Heneicosylic acid (C21:0) | 0.19 ± 0.01 a | 0.14 ± 0.00 d | nd | nd | nd | 0.15 ± 0.00 c | 0.20 ± 0.00 a | nd | 0.18 ± 0.00 b | nd |

| Eicosadienoic acid (C20:2) | 0.24 ± 0.02 fg | 0.25 ± 0.00 f | 2.25 ± 0.02 a | 0.52 ± 0.01 c | 0.49 ± 0.01 d | 0.25 ± 0.00 f | 0.26 ± 0.00 f | 1.31 ± 0.01 b | 0.22 ± 0.00 g | 0.43 ± 0.01 e |

| Behenic acid (C22:0) | 0.04 ± 0.01 d | 0.05 ± 0.00 c | nd | 0.11 ± 0.00 a | 0.10 ± 0.00 b | 0.06 ± 0.00 c | 0.04 ± 0.00 d | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 0.03 ± 0.00 d | 0.04 ± 0.00 d |

| Dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (C20:3 n6) | nd | nd | 0.12 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.00 b | 0.04 ± 0.00 b | nd | nd | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | nd | 0.02 ± 0.00 c |

| Tricosylic acid (C23:0) | nd | nd | 2.15 ± 0.00 a | 0.36 ± 0.00 c | 0.27 ± 0.00 d | nd | nd | 1.08 ± 0.03 b | nd | 0.26 ± 0.01 d |

| Arachidonic acid (C20:4 n6) | 0.10 ± 0.00 c | 0.11 ± 0.00 c | 2.15 ± 0.00 a | 0.08 ± 0.00 d | 0.08 ± 0.00 d | 0.10 ± 0.00 c | 0.10 ± 0.00 c | 0.15 ± 0.00 b | 0.08 ± 0.00 d | 0.04 ± 0.02 e |

| Docosadienoic acid (C22:2) | 0.02 ± 0.00 d | 0.03 ± 0.00 d | 1.64 ± 0.05 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 c | 0.20 ± 0.00 c | 0.02 ± 0.00 d | 0.02 ± 0.00 d | 0.81 ± 0.12 b | 0.02 ± 0.00 d | 0.20 ± 0.04 c |

| Lignoceric acid (C24:0) | 0.04 ± 0.01 efg | 0.05 ± 0.00 e | 0.43 ± 0.02 a | 0.11 ± 0.00 c | 0.10 ± 0.01 c | 0.05 ± 0.00 ef | 0.03 ± 0.00 fg | 0.29 ± 0.00 b | 0.02 ± 0.00 g | 0.08 ± 0.00 d |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5 n3) | 0.03 ± 0.02 b | 0.05 ± 0.00 a | nd | nd | nd | 0.05 ± 0.00 a | 0.01 ± 0.00 bc | nd | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | nd |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6 n3) | nd | nd | 0.72 ± 0.01 a | 0.10 ± 0.00 c | 0.09 ± 0.01 c | nd | nd | 0.32 ± 0.0 b | nd | 0.09 ± 0.01 c |

| Saturated fatty acids (SFAs) | 36.37 ± 1.18 f | 36.20 ± 0.05 f | 39.00 ± 0.19 a | 37.40 ± 0.05 de | 38.74 ± 0.06 ab | 35.94 ± 0.02 f | 37.05 ± 0.07 e | 39.33 ± 0.20 a | 37.90 ± 0.06 cd | 38.26 ± 0.15 bc |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) | 28.94 ± 0.83 de | 27.82 ± 0.06 g | 27.99 ± 0.11 fg | 28.91 ± 0.03 de | 29.23 ± 0.04 cd | 28.49 ± 0.03 ef | 29.58 ± 0.09 c | 28.77 ± 0.05 de | 31.01 ± 0.04 a | 30.36 ± 0.14 b |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) | 34.69 ± 1.97 bc | 35.98 ± 0.02 a | 33.01 ± 0.14 de | 33.69 ± 0.05 cd | 32.04 ± 0.04 ef | 35.57 ± 0.03 ab | 33.37 ± 0.07 d | 31.90 ± 0.18 ef | 31.09 ± 0.02 g | 31.38 ± 0.15 g |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sadubsarn, D.; Muangrat, R. Sustainable Valorization of Crickets: Optimized Low-Pressure Supercritical CO2 Extraction and the Oil’s Properties and Stability. Foods 2026, 15, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010114

Sadubsarn D, Muangrat R. Sustainable Valorization of Crickets: Optimized Low-Pressure Supercritical CO2 Extraction and the Oil’s Properties and Stability. Foods. 2026; 15(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadubsarn, Dolaya, and Rattana Muangrat. 2026. "Sustainable Valorization of Crickets: Optimized Low-Pressure Supercritical CO2 Extraction and the Oil’s Properties and Stability" Foods 15, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010114

APA StyleSadubsarn, D., & Muangrat, R. (2026). Sustainable Valorization of Crickets: Optimized Low-Pressure Supercritical CO2 Extraction and the Oil’s Properties and Stability. Foods, 15(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010114