Interaction of Hazelnut-Derived Polyphenols with Biodegradable Film Matrix: Structural, Barrier, and Functional Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

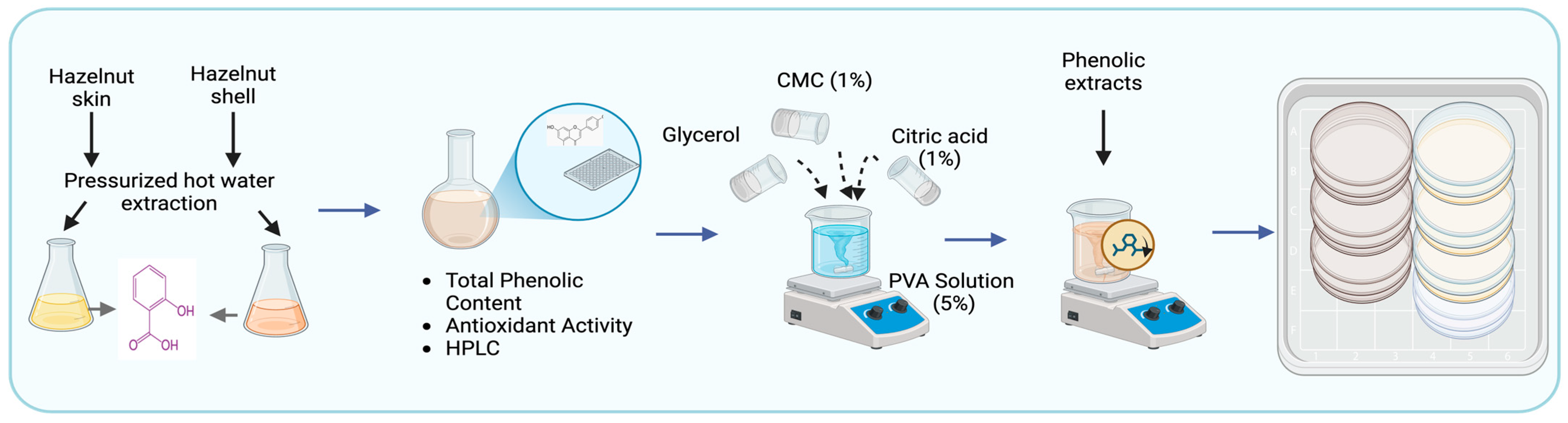

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Extraction of Polyphenols from Hazelnut Shell (HSh) and Skin (HSk)

2.3. Characterization of Hazelnut Shell (HShE) and Hazelnut Skin Extract (HSkE)

2.3.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.3.2. Total Antioxidant Activity (TAA)

2.3.3. High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

2.4. Fabrication of Biodegradable Composite Films

2.5. Film Properties

2.5.1. Structural Properties (FTIR, XRD)

2.5.2. Thermal Properties (DSC)

2.5.3. Optical Properties

2.5.4. Mechanical Properties

2.5.5. Barrier Properties (Water Vapor Permeability (WVP), Oxygen Permeability (OP))

2.5.6. Antioxidant Activity (AA) of Films

DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl)

CUPRAC (Copper (II) Reducing Antioxidant Capacity)

2.5.7. Biodegradation Analysis

2.6. Applications of the Films on Fresh Fruits and Chicken

2.6.1. Appearance

2.6.2. Weight Loss

2.6.3. Antibacterial Activity (AbA) of Composite Films

2.6.4. Lipid Oxidation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

3.2. Total Antioxidant Activity (TAA)

3.3. Quantification and Identification of Phenolic Compounds in Hazelnut By-Products by High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

3.4. Film Properties

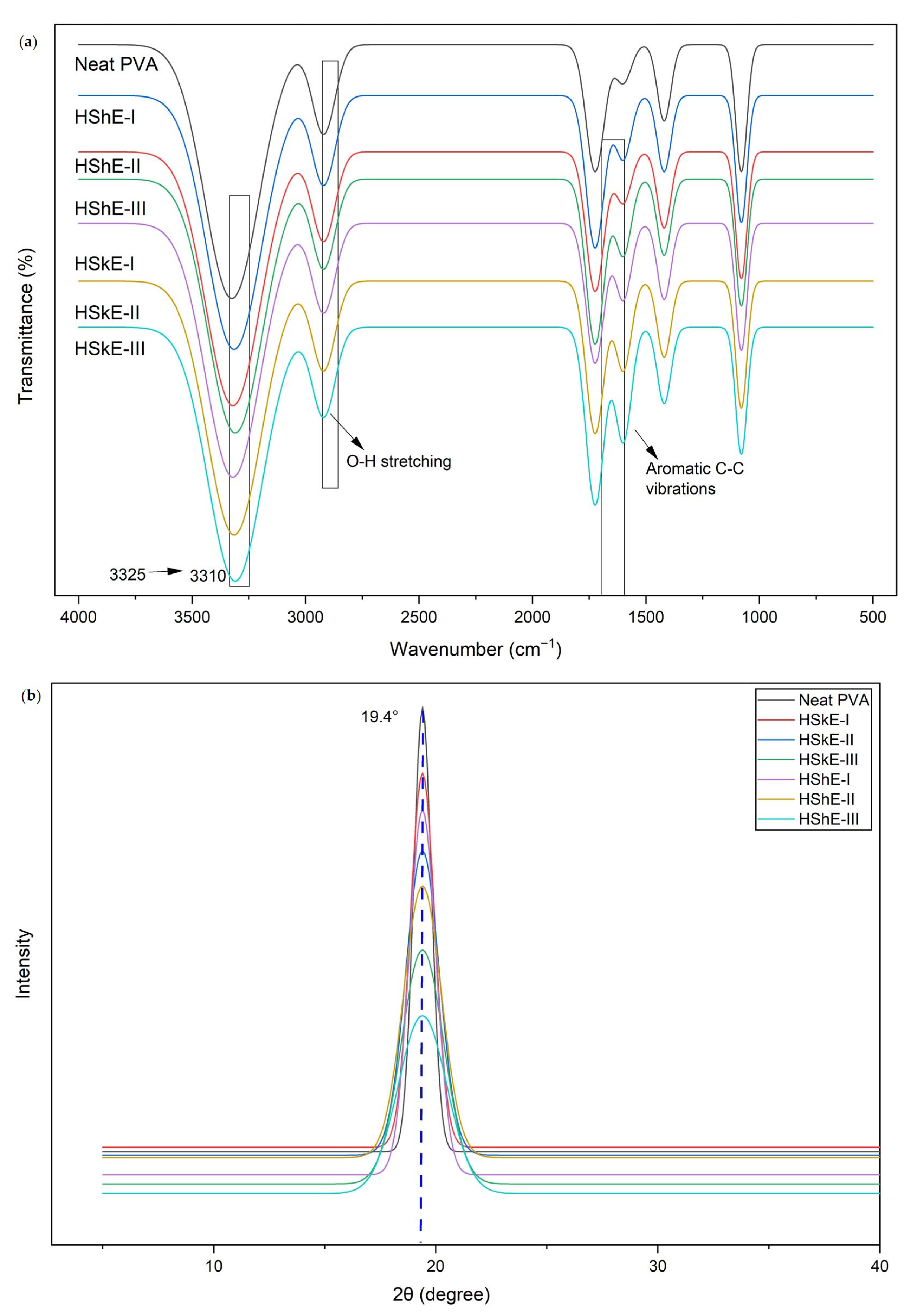

3.4.1. Structural Analysis (FTIR, XRD)

3.4.2. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

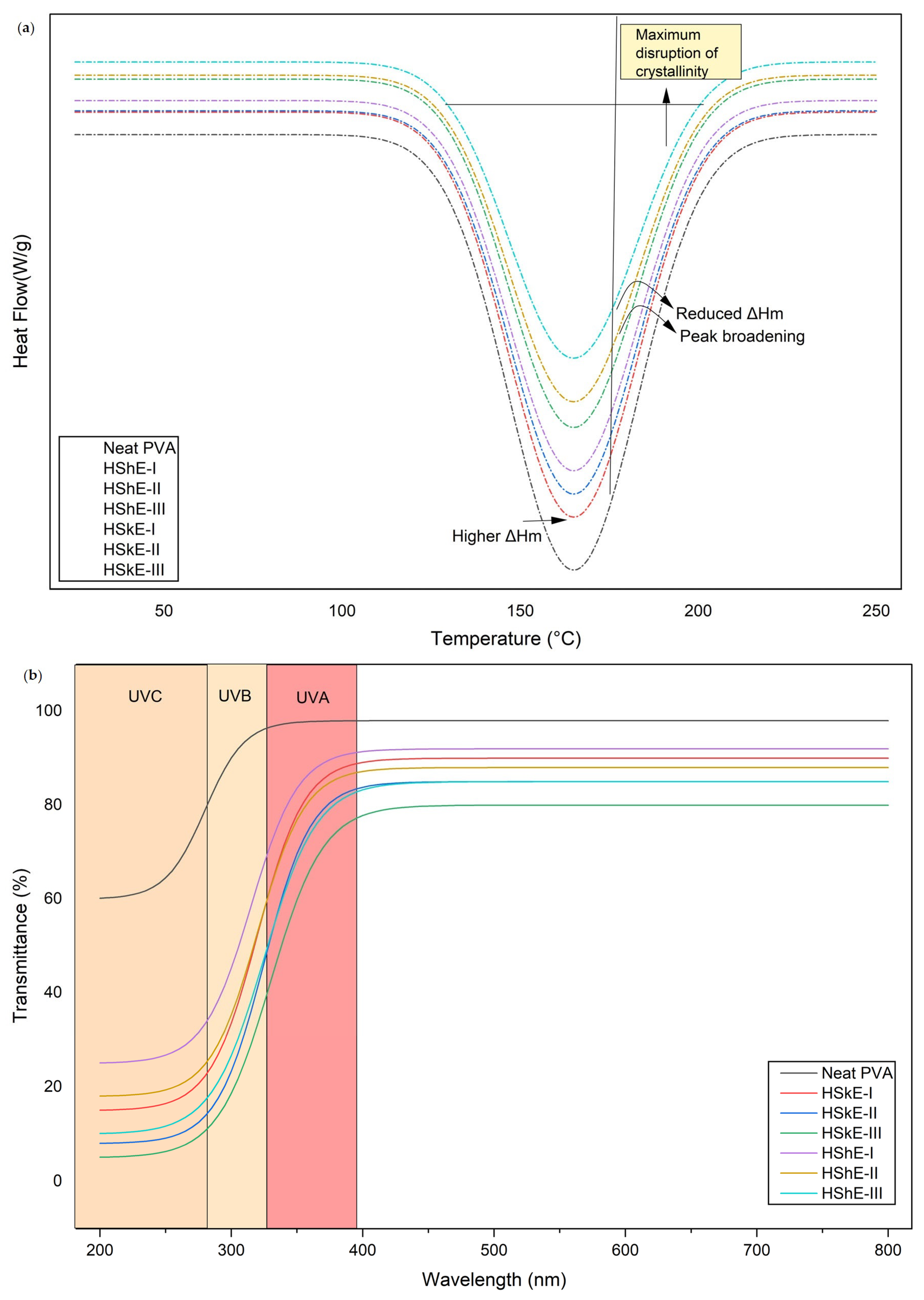

3.4.3. Thermal Properties (DSC)

3.4.4. Optical Properties

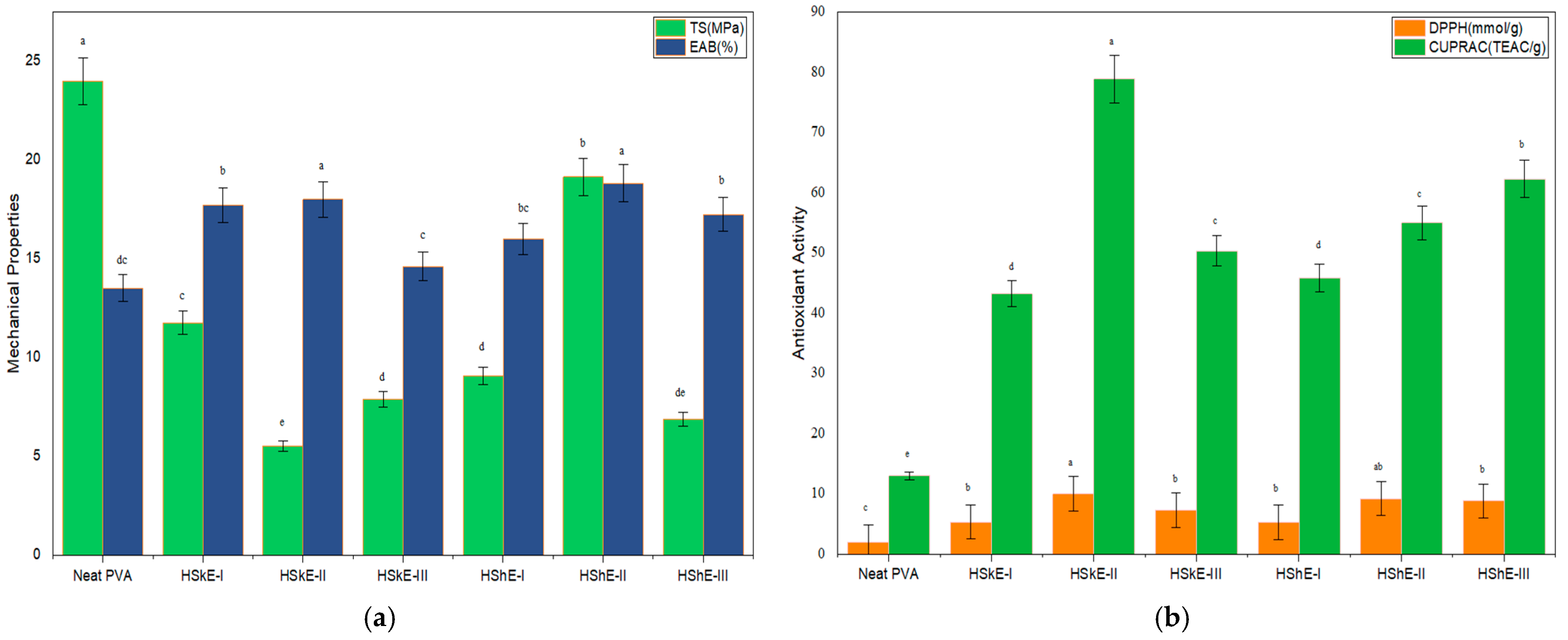

3.4.5. Mechanical Properties

3.4.6. Barrier Properties (WVP, OP)

3.4.7. Antioxidant Activity (AA)

3.4.8. Biodegradation Analysis

3.5. Applications of the Films on Fresh Fruits and Chicken

3.5.1. Appearance and Color

3.5.2. Weight Loss

3.5.3. Microbial Evaluation

3.5.4. Lipid Oxidation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The State of Food and Agriculture—2019 Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdfFAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U. Global Food Losses and Food Waste; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Manterola-Barroso, C.; Contreras, D.P.; Ondrasek, G.; Horvatinec, J.; Gavilán Cui, G. Hazelnut and Walnut Nutshell Features as Emerging Added-Value by Products of the Nut Industry: A review. Plants 2024, 13, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, N.; Gökmen, V.; Jaros, D. Bioactive Compounds in Different Hazelnut Varieties and Their Skins; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanović, S.; Avramović, N.; Dojčinović, B.; Trifunović, S.; Novaković, M.; Tešević, V.; Mandić, B. Chemical Composition, Total Phenols and Flavonoids Contents and Antioxidant Activity as Nutritive Potential of Roasted Hazelnut Skins (Corylus avellana L.). Foods 2020, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Armada, L.; Rivas, S.; González, B.; Moure, A. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Hazelnut Shells by Green Processes. J. Food Eng. 2019, 255, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, R.; Hemming, J.; Smeds, A.; Gordobil, O.; Willför, S.; Labidi, J. Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from Hazelnuts and Walnuts Shells: Quantitative–Qualitative Analysis and Chromatographic Purification. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montella, R.; Coïsson, J.D.; Travaglia, F.; Locatelli, M.; Malfa, P.; Martelli, A.; Arlorio, M. Bioactive Compounds from Hazelnut Skin (Corylus avellana L.): Effects on Lactobacillus Plantarum P17630 and Lactobacillus Crispatus P17631. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasalvar, C.; Shahidi, F.; Amarai, J.S.; Oliveira, B.P.P. Compositional Characteristics and Health Effects of Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.): An Overview. In Tree Nuts; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Murphy, R.J.; Narayan, R.; Davies, G.B.H. Biodegradable and Compostable Alternatives to Conventional Plastics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2127–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaikwad, K.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S. Development of Polyvinyl Alcohol and Apple Pomace Bio-Composite Film with Antioxidant Properties for Active Food Packaging Application. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, S.A.; Pulikkalparambil, H.; Rangappa, S.M.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Siengchin, S. Antimicrobial active packaging based on PVA/Starch films incorporating basil leaf extracts. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 72, 3056–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Gaikwad, K.K.; Lee, Y.S. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol Bio Composite Films Containing Seaweed Extracted Cellulose Nano-Crystal and Basil Leaves Extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1879–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkede, F.N.; Wardana, A.A.; Phuong, N.T.H.; Takahashi, M.; Koga, A.; Wardak, M.H.; Fanze, M.; Tanaka, F. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan/Lemongrass Oil/Cellulose Nanofiber Pickering Emulsions Active Packaging and Its Application on Tomato Preservation. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 4930–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, G.; Voss, M.; Tabasso, S.; Stefanetti, V.; Branciari, R.; Chaji, S.; Grillo, G.; Cravotto, C.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Fiego, D.P.L.; et al. Upgrading Hazelnut Skins: Green Extraction of Polyphenols from Lab to Semi-Industrial Scale. Food Chem. 2024, 463, 140999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Michele, A.; Pagano, C.; Allegrini, A.; Blasi, F.; Cossignani, L.; Di Raimo, E.; Faieta, M.; Oliva, E.; Pittia, P.; Primavilla, S.; et al. Hazelnut Shells as Source of Active Ingredients: Extracts Preparation and Characterization. Molecules 2021, 26, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertdinç, Z.; Aydar, E.F.; Kadı, İ.H.; Demircan, E.; Koca Çetinkaya, S.; Özçelik, B. A New Plant-Based Milk Alternative of Pistacia Vera Geographically Indicated in Türkiye: Antioxidant Activity, in Vitro Bio-Accessibility, and Sensory Characteristics. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Karademir, S.E. Novel Total Antioxidant Capacity Index for Dietary Polyphenols and Vitamins C and E, Using Their Cupric Ion Reducing Capability in the Presence of Neocuproine: CUPRAC Method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7970–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, R.; Shruthy, R.; Preetha, R.; Sreejit, V. Biodegradable Nano Composite Reinforced with Cellulose Nano Fiber from Coconut Industry Waste for Replacing Synthetic Plastic Food Packaging. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.H.; Hung, C.Y.; Chiang, P.C.; Lee, H.; Lin, I.T.; Lai, P.C.; Chan, Y.H.; Feng, S.W. Physicochemical Characterization, Biocompatibility, and Antibacterial Properties of CMC/PVA/Calendula Officinalis Films for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchaiyaphum, P.; Chotichayapong, C.; Kajsanthia, K.; Saengsuwan, N. Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Based Active Film Incorporated with Tamarind Seed Coat Waste Extract for Food Packaging Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 255, 126858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, S. Improved Hydrophobic, UV Barrier and Antibacterial Properties of Multifunctional PVA Nanocomposite Films Reinforced with Modified Lignin Contained Cellulose Nanofibers. Polymers 2022, 14, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E96-00; Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2000.

- Rhim, J.W.; Hong, S.I.; Ha, C.S. Tensile, Water Vapor Barrier and Antimicrobial Properties of PLA/Nanoclay Composite Films. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3985-95; Standard Test Method for Oxygen Gas Transmission Rate Through Plastic Film and Sheeting Using a Coulometric Sensor. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Jridi, M.; Hajji, S.; Ben Ayed, H.; Lassoued, I.; Mbarek, A.; Kammoun, M.; Souissi, N.; Nasri, M. Physical, Structural, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Gelatin–Chitosan Composite Edible Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 67, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5988-12; Standard Test Method for Determining Aerobic Biodegradation of Plastic Materials in Soil. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2000.

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmad, M.; Swami, B.L.; Ikram, S. A Review on Plants Extract Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles for Antimicrobial Applications: A Green Expertise. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, J.; Holt, D.; Aldrich, C.G.; Knueven, C. Effects of Antimicrobial Addition on Lipid Oxidation of Rendered Chicken Fat. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2022, 6, txac011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, F.D.; Adrar, N.; Bolling, B.W.; Capanoglu, E. Valorisation of Hazelnut by-Products: Current Applications and Future Potential. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2023, 39, 586–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, B.; Lu, M.; Eskridge, K.M.; Isom, L.D.; Hanna, M.A. Extraction, Identification, and Quantification of Antioxidant Phenolics from Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) Shells. Food Chem. 2018, 244, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, B.; Lu, M.; Eskridge, K.M.; Hanna, M.A. Valorization of Hazelnut Shells into Natural Antioxidants by Ultrasound-assisted Extraction: Process Optimization and Phenolic Composition Identification. J. Food Process. Eng. 2018, 41, e12692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, A.; Aguilera, J.M. Size Reduction and Particle Size Influence the Quantification of Phenolic-Type Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Plant Food Matrices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 162, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmas, E.; Şen, F.B.; Kublay, I.Z.; Baş, Y.; Tüfekci, F.; Derman, H.; Bekdeşer, B.; Aşçı, Y.S.; Capanoglu, E.; Bener, M.; et al. Green Extraction of Antioxidants from Hazelnut By-Products Using Microwave-Assisted Extraction, Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction, and Pressurized Liquid Extraction. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 5388–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Alasalvar, C.; Liyana-Pathirana, C.M. Antioxidant Phytochemicals in Hazelnut Kernel (Corylus avellana L.) and Hazelnut Byproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stévigny, C.; Rolle, L.; Valentini, N.; Zeppa, G. Optimization of Extraction of Phenolic Content from Hazelnut Shell Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 2817–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, M.; Baccelloni, S.; Massantini, R.; Anelli, G. Extraction of Natural Antioxidants from Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) Shell and Skin Wastes by Long Maceration at Room Temperature. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, M.; Cerulli, A.; Mari, A.; de Souza Santos, C.C.; Pizza, C.; Piacente, S. LC-MS Profiling Highlights Hazelnut (Nocciola Di Giffoni PGI) Shells as a Byproduct Rich in Antioxidant Phenolics. Food Res. Int. 2017, 101, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, M.; Belviso, S.; Dal Bello, B.; Ghirardello, D.; Giordano, M.; Rolle, L.; Gerbi, V.; Zeppa, G. Influence of the addition of different hazelnut skins on the physicochemical, antioxidant, polyphenol and sensory properties of yogurt. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, T.; Sansone, F.; Franceschelli, S.; Del Gaudio, P.; Picerno, P.; Aquino, R.P.; Mencherini, T. Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) Shells Extract: Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant Effect and Cytotoxic Activity on Human Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Calani, L.; Dall’Asta, M.; Brighenti, F. Polyphenolic Composition of Hazelnut Skin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9935–9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Jiao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lv, Z.; Yang, W.; Chen, D.; Liu, H. Polysaccharide-Based Packaging Coatings and Films with Phenolic Compounds in Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables—A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harun-Or-Rashid, M.D.; Rahaman, M.D.S.; Kabir, S.E.; Khan, M.A. Effect of Hydrochloric Acid on the Properties of Biodegradable Packaging Materials of Carboxymethylcellulose/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 42870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Jiao, C.; Li, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Yuan, X. A Facile Strategy for Development of pH-Sensing Indicator Films Based on Red Cabbage Puree and Polyvinyl Alcohol for Monitoring Fish Freshness. Foods 2022, 11, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Wang, H.; Xia, L.; Chen, M.; Li, L.; Cheng, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, S. Colorimetric Film Based on Polyvinyl Alcohol/Okra Mucilage Polysaccharide Incorporated with Rose Anthocyanins for Shrimp Freshness Monitoring. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Tu, L.; Xu, A.; Zhao, Y.; Ye, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, P. Structural Diversity of Tea Phenolics Modulates Physicochemical Properties and Digestibility of Wheat Starch: Insights into Gallic Acid Group-Dependent Interactions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 364, 123763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanzada, B.; Akhtar, N.; Haq, I.U.; Mirza, B.; Ullah, A. Polyphenol Assisted Nano-Reinforced Chitosan Films with Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 153, 110010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Khan, M.R.; Ahmad, N.; Zhang, W.; Goksen, G. Preparation of Polysaccharide-Based Films Synergistically Reinforced by Tea Polyphenols and Graphene Oxide. Food Chem. X 2025, 27, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Hsu, Y.-I.; Asoh, T.-A.; Uyama, H. Antioxidant Activity and Physical Properties of pH-Sensitive Biocomposite Using Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Incorporated with Green Tea Extract. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 178, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zuo, D.; Deng, Z.; Ji, A.; Xia, G. Effects of Heat Treatment and Tea Polyphenols on the Structure and Properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofiber Films for Food Packaging. Coatings 2020, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, B.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, Y.; Essawy, H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J. Facile Fabrication of High-Performance Composite Films Comprising Polyvinyl Alcohol as Matrix and Phenolic Tree Extracts. Polymers 2023, 15, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordoñez, R.; Atarés, L.; Chiralt, A. Biodegradable Active Materials Containing Phenolic Acids for Food Packaging Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3910–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Cao, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Kong, B. Preparation and Functional Properties of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Ethyl Cellulose/Tea Polyphenol Electrospun Nanofibrous Films for Active Packaging Material. Food Control 2021, 130, 108331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhaboot, P.; Kraisuwan, W.; Chatkumpjunjalearn, T.; Kroeksakul, P.; Chongkolnee, B. Development and Characterization of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Bacterial Cellulose Composite for Environmentally Friendly Film. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, S.; Eyüboğlu, S.; Karkar, B.; Ata, G.D. Development of Bioactive Films Loaded with Extract and Polysaccharide of Pinus brutia Bark. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 3649–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, S.P.; Kanatt, S.R.; Sharma, A.K. Chitosan. In Polysaccharides; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, V.; Rocculi, P.; Romani, S.; Rosa, M.D. Biodegradable Polymers for Food Packaging: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.; Muntean, A.; Mesic, B.; Lestelius, M.; Javed, A. Oxygen Barrier Performance of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Coating Films with Different Induced Crystallinity and Model Predictions. Coatings 2021, 11, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripatrawan, U.; Harte, B.R. Physical Properties and Antioxidant Activity of an Active Film from Chitosan Incorporated with Green Tea Extract. Food Hydrocoll. 2010, 24, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P. Effect of Plasticizer and Antimicrobial Agents on Functional Properties of Bionanocomposite Films Based on Corn Starch-Chitosan for Food Packaging Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wei, J.; Wang, C.; Ren, J. Preparation, Physicochemical Properties, Biological Activity of a Multifunctional Composite Film Based on Zein/Citric Acid Loaded with Grape Seed Extract and Its Application in Solid Lipid Packaging. Foods 2025, 14, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Wang, N.; Lu, Y.; Wang, C. Preparation and Characterization of Antioxidative and pH-Sensitive Films Based on κ-Carrageenan/Carboxymethyl Cellulose Blended with Purple Cabbage Anthocyanin for Monitoring Hairtail Freshness. Foods 2025, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suyatma, N.E.; Copinet, A.; Tighzert, L.; Coma, V. Mechanical and Barrier Properties of Biodegradable Films Made from Chitosan and Poly (Lactic Acid) Blends. J. Polym. Environ. 2004, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Hu, W.; Jiang, A.; Tian, M.; Li, Y. Extending Shelf-Life of Fresh-Cut ‘Fuji’ apples with Chitosan-Coatings. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2011, 12, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Yang, X.; He, C. Influence of Multiple Environmental Factors on the Quality and Flavor of Watermelon Juice. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 15289–15297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, S.; Benjakul, S.; Abushelaibi, A.; Alam, A. Phenolic Compounds and Plant Phenolic Extracts as Natural Antioxidants in Prevention of Lipid Oxidation in Seafood: A Detailed Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Silva, M.; Farinha, D.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J. Edible Coatings and Future Trends in Active Food Packaging–Fruits’ and Traditional Sausages’ Shelf Life Increasing. Foods 2023, 12, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HShE | HSkE | |

|---|---|---|

| TPC (mg GAE/g dw) (Folin–Ciocalteu) | 25.44 ± 1.42 a | 83.68 ± 2.69 b |

| TAA (mg TEAC/g dw) (CUPRAC) | 331.23 ± 10.5 a | 638.47 ± 9.8 b |

| Phenolic Compound (mg/100 mL) | ||

| Gallic Acid | 6.89 | 36.05 |

| Catechin | 0.90 | 438 |

| Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) | 11.27 | 88.84 |

| Vanillic Acid | 3.65 | 29.13 |

| Syringic Acid | <0.1 | 12.71 |

| Vanillin | 6.32 | ND |

| Rutin | ND | 16.68 |

| Trans-Cinnamic Acid | 0.13 | <0.1 |

| Sample Name | L* | a* | b* | ΔE | Thickness (mm) | WVP (g·mm/m2·h·kPa) | OP (cm3mm/m2·day·atm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat PVA | 85.05 b | 0.98 e | −1.39 d | 1.10 d | 0.045 d | 10.4 × 10−2 a | 0.048 a |

| HSkE-I | 85.23 b | 1.007 d | 1.78 b | 3.17 c | 0.079 b | 9.88 × 10−2 b | 0.031 b |

| HSkE-II | 84.22 d | 1.007 d | 1.28 b | 4.03 b | 0.084 a | 9.48 × 10−2 b | 0.023 c |

| HSkE-III | 83.28 e | 1.25 c | 1.007 c | 6.24 a | 0.090 a | 11.5 × 10−2 a | 0.015 d |

| HShE-I | 86.29 a | 1.64 a | 2.79 a | 5.52 a | 0.069 c | 8.8 × 10−2 c | 0.035 b |

| HShE-II | 86.37 a | 1.68 a | 2.30 a | 5.53 a | 0.076 b | 9.5 × 10−2 b | 0.025 c |

| HShE-III | 84.84 c | 1.51 b | 2.27 a | 5.12 a | 0.084 a | 10.7 × 10−2 a | 0.016 d |

| Sample Name | Storage Time (Days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | |

| Uncoated | 6.21 ± 0.1 a | 7.19 ± 0.2 a | 8.23 ± 0.8 a | 107.23 ± 9.8 a |

| Stretch film | 6.25 ± 0.3 a | 4.23 ± 0.25 a | 4.52 ± 0.23 a | 67.02 ± 0.2 b |

| Neat PVA | 6.24 ± 0.2 a | 6.21 ± 0.12 a | 7.01 ± 0.23 c | 55.12 ± 1.8 c |

| HShE-I | 6.32 ± 0.32 a | 4.79 ± 0.18 a | 5.02 ± 1.8 d | 47.19 ± 0.8 d |

| HShE-II | 6.28 ± 0.23 a | 4.01 ± 0.13 a | 5.19 ± 0.28 d | 27.9 ± 0.38 d |

| HShE-III | 6.2 ± 0.21 a | 5.53 ± 0.23 a | 6.07 ± 0.8 e | 37.12 ± 0.5 e |

| HSkE-I | 6.25 ± 0.18 a | 5.32 ± 0.13 a | 7.22 ± 0.23 c | 53.17 ± 0.3 c |

| HSkE-II | 6.29 ± 0.31 a | 4.21 ± 0.28 a | 5.24 ± 0.21 cd | 45.23 ± 2.1 cd |

| HSkE-III | 6.19 ± 0.27 a | 5.29 ± 0.28 a | 6.02 ± 0.4 d | 53.2 ± 0.8 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hızır-Kadı, I.; Demircan, E.; Özçelik, B. Interaction of Hazelnut-Derived Polyphenols with Biodegradable Film Matrix: Structural, Barrier, and Functional Properties. Foods 2026, 15, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010107

Hızır-Kadı I, Demircan E, Özçelik B. Interaction of Hazelnut-Derived Polyphenols with Biodegradable Film Matrix: Structural, Barrier, and Functional Properties. Foods. 2026; 15(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleHızır-Kadı, Ilayda, Evren Demircan, and Beraat Özçelik. 2026. "Interaction of Hazelnut-Derived Polyphenols with Biodegradable Film Matrix: Structural, Barrier, and Functional Properties" Foods 15, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010107

APA StyleHızır-Kadı, I., Demircan, E., & Özçelik, B. (2026). Interaction of Hazelnut-Derived Polyphenols with Biodegradable Film Matrix: Structural, Barrier, and Functional Properties. Foods, 15(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010107