Development of Hybrid Pleurotus cystidiosus Strains with Enhanced Functional Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strains

2.2. Monospore Isolation and Mating

2.3. Substrate Composition

2.4. Cultivation and Growth Evaluation

2.5. Estimate of Heritability

2.6. Measurement of Polysaccharide Content [34]

2.7. Measurement of Total Phenolic Content

2.8. Measurement of Ergothioneine Content [36]

2.9. Measurement of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.10. Measurement of α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Development of Hybrid Strains of P. cystidiosus

3.2. Cultivation Characteristics

3.3. Stage-Specific Growth Characteristics

3.4. Estimation of Heritability on Agronomic Traits

3.5. Total Polysaccharide Content

3.6. Ergothioneine Content

3.7. Total Phenolic Content

3.8. Antioxidant Activity

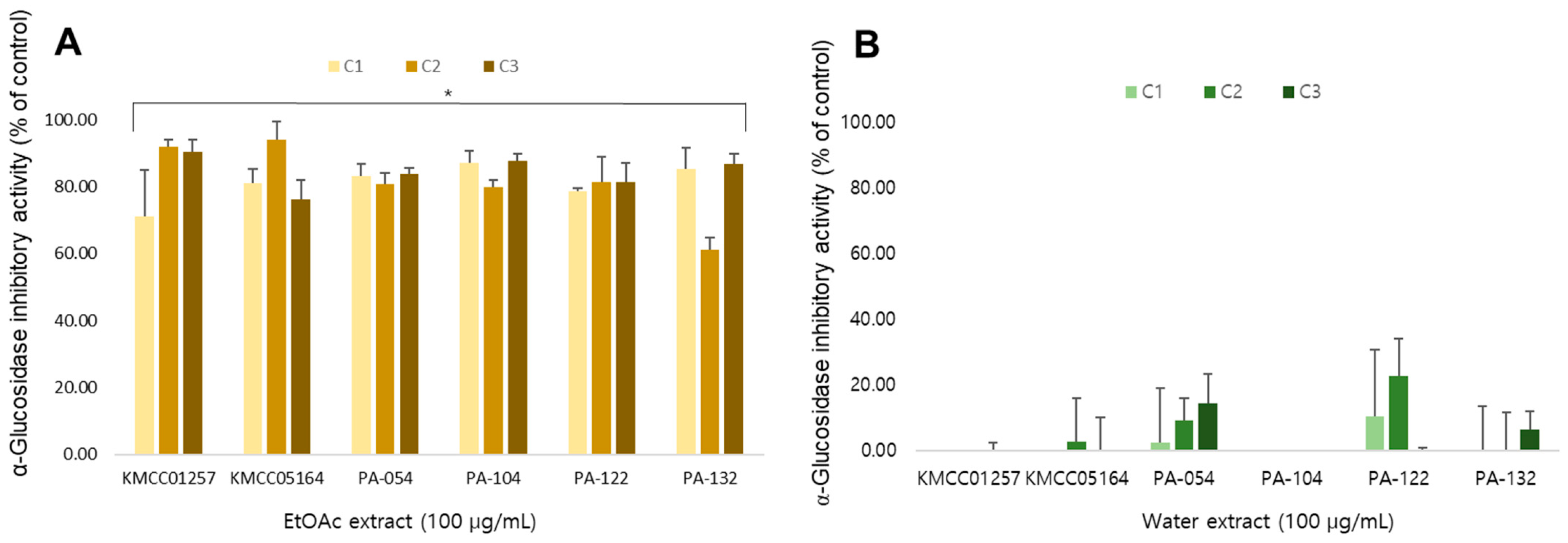

3.9. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EtOAc | Ethyl acetate |

| PDA | Potato dextrose agar |

References

- Ahmad, R.; Riaz, M.; Khan, A.; Aljamea, A.; Algheryafi, M.; Sewaket, D.; Alqathama, A. Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) an edible mushroom; a comprehensive and critical review of its nutritional, cosmeceutical, mycochemical, pharmacological, clinical, and toxicological properties. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 6030–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, M. Chemistry, nutrition, and health-promoting properties of Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane) mushroom fruiting bodies and mycelia and their bioactive compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7108–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, F.; Peng, X.; Zhao, G.; Zeng, J.; Zou, J.; Rao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, H.; Zeng, N. Structural diversity and bioactivity of polysaccharides from medicinal mushroom Phellinus spp.: A review. Food Chem. 2022, 397, 133731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, D.D.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Recent developments in Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides: Extraction, purification, structural characteristics and biological activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, S96–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Thorne, J.L.; Moore, J.B. Ergothioneine: An underrecognised dietary micronutrient required for healthy ageing? Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Zeng, N.K.; Xu, B. Chemical profiles and health-promoting effects of porcini mushroom (Boletus edulis): A narrative review. Food Chem. 2022, 390, 133199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhao, J.; Gan, B.; Feng, R.; Miao, R. Polysaccharides derived from mushrooms in immune and antitumor activity: A review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2023, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohretoglu, D.; Huang, S. Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides as an anti-cancer agent. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, I.; Bouftini, K.; Hmidouche, O.; Rchid, H.; Ursu, A.V.; Lasky, M.; Gardarin, C.; Moznine, R.; Vial, C.; Nmila, R. Crude polysaccharides from Cystoseira species: Extraction, characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2025, 31, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Ren, L.J. The current status of biotechnological production and the application of a novel antioxidant ergothioneine. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Chen, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, R.; Chen, C.; Zhang, M.; Ma, T. The roles and functions of ergothioneine in metabolic diseases. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 141, 109895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelshafy, A.M.; Belwal, T.; Liang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Luo, Z.; Li, L. A comprehensive review on phenolic compounds from edible mushrooms: Occurrence, biological activity, application and future prospective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6204–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rašeta, M.; Popović, M.; Knežević, P.; Šibul, F.; Kaišarević, S.; Karaman, M. Bioactive phenolic compounds of two medicinal mushroom species Trametes versicolor and Stereum subtomentosum as antioxidant and antiproliferative agents. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, P.S.; Khairuddin, S.; Tse, A.C.K.; Hiew, L.F.; Lau, C.L.; Tipoe, G.L.; Fung, M.L.; Wong, K.H.; Lim, L.W. Production of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) from some waste lignocellulosic materials and FTIR characterization of structural changes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, H.; Kushwaha, A.; Behera, P.C.; Shahi, N.C.; Kushwaha, K.P.S.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, K.K. The pink oyster mushroom, Pleurotus djamor (Agaricomycetes): A potent antioxidant and hypoglycemic agent. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2021, 23, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugbogu, E.A.; Israel, C.L.; Akubugwo, E.I.; Arunsi, U.O.; Nwaru, E.C.; Owumi, S.; Nwankwo, V. The king tuber medicinal mushroom Pleurotus tuberregium (Agaricomycetes): A review on nutritional composition, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, and toxicity profile. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2025, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, A.; Tripathi, A. Biological activities of Pleurotus spp. polysaccharides: A review. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barh, A.; Sharma, V.P.; Annepu, S.K.; Kamal, S.; Sharma, S.; Bhatt, P. Genetic improvement in Pleurotus (oyster mushroom): A review. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.T.; Miles, P.G. Sexuality and the genetics of basidiomycetes. In Edible Mushrooms and Their Cultivation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; Chapter 5; pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, S.; Huang, Z.; Yin, L.; Hu, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Rong, C. Development of a highly productive strain of Pleurotus tuoliensis for commercial cultivation by crossbreeding. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, S.; Theradimani, M.; Vellaikumar, S.; Paramasivam, M.; Ramamoorthy, V. Development of novel rapid-growing and delicious Pleurotus djamor strains through hybridization. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 206, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosnina, A.G.; Tan, Y.S.; Abdullah, N.; Vikineswary, S. Morphological and molecular characterization of yellow oyster mushroom, Pleurotus citrinopileatus, hybrids obtained by interspecies mating. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswal, R.K.; Sodhi, H.S.; Sharma, S. Characterization of interspecific hybrid dikaryons of the oyster mushrooms, Pleurotus florida PAU-5 and P. sajor-caju PAU-3 (higher Basidiomycetes) from India. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2014, 16, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, K.; Kar, M.E.; Maity, S.; Gantait, S.K.; Das, D.; Maiti, S.; Maiti, T.K.; Sikdar, S.R.; Islam, S.S. Chemical analysis and study of immunoenhancing and antioxidant property of a glucan isolated from an alkaline extract of a somatic hybrid mushroom of Pleurotus florida and Calocybe indica variety APK2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 49, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, D.; Kinugasa, S.; Kitamoto, Y. The biological species of Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.) from Asia based on mating compatability test. J. Wood Sci. 2004, 50, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, C.H.; Kim, M.K.; Je, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Ryu, S.J. Introduction of a speedy growing trait into Pleurotus eryngii by backcrossing. J. Mushroom 2012, 10, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, K.Y.; Jhune, C.S.; Shin, C.W.; Park, J.S.; Cheong, J.C.; Choi, S.G.; Sung, J.M. Studies on the morphological and physiological characteristics of Pleurotus cystidiosus O. K. Miller, the abalone mushroom. Korean J. Mycol. 2003, 31, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, M.J.; Im, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, D.H.; Lee, E.J.; Woo, S.I.; Oh, Y.L. Breeding a new cultivar of Pleurotus ostreatus, ‘Otari’ and its characteristics. J. Mushroom 2024, 22, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.M.; Yoo, D.R.; Oh, T.S.; Park, Y.J.; Jang, M.J. Changes in the microbial community of substrate and fruit body of Pleurotus ostreatus. J. Mushroom 2024, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, K.Y.; Jhune, C.S.; Shin, C.W.; Park, J.S.; Cheong, J.C.; Choi, S.G.; Sung, J.M. Studies on the artificial cultivation of Pleurotus cystidiosus O. K. Miller, the abalone mushroom. Korean J. Mycol. 2003, 31, 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Camel, L.; Min, Z.; Mohanad, B.; Fatoumata, T. Effects of pressurized argon and krypton treatments on the quality of fresh white mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 4, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Chaudhary, B.D. Biometrical Methods in Quantitative Genetic Analysis, 3rd ed.; Kalyani Publishers: New Delhi, India, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sary, D.N.; Badriyah, L.; Sihombing, R.D.; Syanqy, T.A.; Mustikarinini, E.D.; Prayoga, G.I.; Waluyo, R.S. Estimation of heritability and association analysis of agronomic traits contributing to yield on upland rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfias, S.V.; Cordova, A.M.S.; Ascanio, G.; Aguayo, J.P.; Pérez-Salas, K.Y.; Susunaga, N.A.D.C. Acid hydrolysis of pectin and mucilage from Cactus (Opuntia ficus) for identification and quantification of monosaccharides. Molecules 2022, 27, 5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Jo, Y.H.; Liu, Q.; Ahn, J.H.; Hong, I.P.; Han, S.M.; Hwang, B.Y.; Lee, M.K. Optimization of extraction condition of bee pollen using response surface methodology: Correlation between anti-melanogenesis, antioxidant activity, and phenolic content. Molecules 2015, 20, 19764–19774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiantas, K.; Tsiaka, T.; Koutrotsios, G.; Siapi, E.; Zervakis, G.I.; Kalogeropoulos, N.; Zoumpoulakis, P. On the identification and quantification of ergothioneine and lovastatin in various mushroom species: Assets and challenges of different analytical approaches. Molecules 2021, 26, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.H.; Lee, S.; Yeon, S.W.; Ryu, S.H.; Turk, A.; Hwang, B.Y.; Han, Y.K.; Lee, K.Y.; Lee, M.K. Anti-α-glucosidase and anti-oxidative isoflavonoids from the immature fruits of Maclura tricuspidata. Phytochemistry 2022, 194, 113016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.H.; Ahn, J.H.; Turk, A.; Kim, S.B.; Hwang, B.Y.; Lee, M.K. Argutinic acid, a new triterpenoid from the fruits of Actinidia arguta. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2024, 30, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenkom, E.; Kuznetsovam, O. The influence of complex additives on the synthesis of aroma substances by gray oyster culinary-medicinal mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus (Agaricomycetes) during the substrate cultivation. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2020, 22, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Shah, N.P. Effects of various heat treatments on phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities of Pleurotus eryngii extracts. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, C1122-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Y.; Chien, S.C.; Wang, S.Y.; Mau, J.L. Submerged cultivation of mycelium with high ergothioneine content from the culinary-medicinal golden oyster mushroom, Pleurotus citrinopileatus (Higher Basidiomycetes). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2015, 17, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monika, G.; Mirosław, M.; Marek, S.; Przemysław, N. Phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus eryngii enriched with selenium and zinc. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 723–732. [Google Scholar]

- Petraglia, T.; Latronico, T.; Fangliulo, A.; Crescenzi, A.; Liuzzi, G.M.; Rossano, R. Antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from the edible mushroom Pleurotus eryngii. Molecules 2023, 28, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Isolates | Stage | Pileus | Stipe | Productivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (mm) | Height (mm) | Thickness (mm) | Length (mm) | Individual Weight (g) | Yield (g/800 mL Bag) | ||

| KMCC 01257 | C1 | 58.5 ± 0.7 c | 58.5 ± 11.8 b | 12.9 ± 0.9 a | 34.3 ± 44.6 a | 19.4 ± 5.1 c | 58.2 ± 2.8 a |

| C2 | 72.7 ± 31.2 b | 59.1 ± 23.1 b | 11.2 ± 5.4 b | 8.7 ± 17.5 c | 20.2 ± 8.8 b | 57.8 ± 25.8 a | |

| C3 | 97.9 ± 41.8 a | 71.0 ± 19.3 a | 10.6 ± 3.8 c | 17.5 ± 22.6 b | 32.1 ± 9.7 a | 53.1 ± 17.7 b | |

| KMCC 05164 | C1 | 76.2 ± 5.1 b | 63.0 ± 21.7 c | 10.1 ± 2.1 b | 16.5 ± 6.0 b | 24.8 ± 4.9 c | 58.3 ± 11.8 b |

| C2 | 89.3 ± 33.7 a | 84.2 ± 25.4 a | 19.0 ± 7.3 a | 13.9 ± 6.0 b | 31.8 ± 10.8 b | 48.4 ± 19.1 b | |

| C3 | 95.2 ± 26.5 a | 77.0 ± 23.6 b | 14.9 ± 5.5 a | 19.4 ± 7.0 a | 36.2 ± 10.6 a | 52.5 ± 18.6 a | |

| PA-054 | C1 | 60.9 ± 6.7 b | 42.0 ± 25.2 b | 22.3 ± 5.5 a | 19.3 ± 8.0 a | 34.5 ± 3.8 a | 54.5 ± 23.6 a |

| C2 | 80.2 ± 2.6 a | 55.0 ± 7.8 ab | 14.9 ± 3.5 b | 11.4 ± 10.1 b | 29.5 ± 16.5 b | 54.7 ± 21.3 a | |

| C3 | 98.6 ± 41.8 a | 59.8 ± 23.8 a | 14.6 ± 5.8 b | 9.3 ± 1.4 b | 26.5 ± 6.1 b | 64.8 ± 27.8 a | |

| PA-104 | C1 | 59.2 ± 1.7 c | 72.3 ± 10.2 a | 12.2 ± 6.6 c | 15.2 ± 4.1 b | 18.8 ± 10.3 c | 71.0 ± 11.0 a |

| C2 | 74.9 ± 29.3 b | 58.1 ± 22.6 c | 14.6 ± 3.8 b | 17.6 ± 6.5 a | 27.0 ± 8.4 a | 57.7 ± 22.2 b | |

| C3 | 86.8 ± 25.7 a | 68.5 ± 20.5 b | 14.9 ± 4.2 a | 14.3 ± 5.9 c | 25.5 ± 9.2 b | 55.1 ± 18.4 b | |

| PA-122 | C1 | 58.9 ± 14.7 c | 51.3 ± 10.9 c | 14.9 ± 5.3 c | 22.6 ± 8.5 c | 22.4 ± 9.6 c | 42.6 ± 14.1 c |

| C2 | 64.7 ± 23.7 b | 57.2 ± 22.1 b | 17.9 ± 7.0 b | 29.8 ± 12.1 b | 27.3 ± 8.8 b | 53.8 ± 20.6 a | |

| C3 | 80.2 ± 21.2 a | 59.1 ± 17.4 a | 19.8 ± 6.4 a | 29.2 ± 9.2 a | 33.8 ± 9.2 a | 47.2 ± 16.3 b | |

| PA-132 | C1 | 58.1 ± 3.2 c | 60.7 ± 8.7 c | 14.8 ± 6.7 c | 20.8 ± 17.4 c | 30.2 ± 9.9 c | 57.2 ± 1.8 c |

| C2 | 62.9 ± 24.1 b | 64.6 ± 27.9 b | 15.5 ± 4.6 b | 28.9 ± 12.7 a | 32.1 ± 17.1 a | 77.4 ± 1.2 a | |

| C3 | 87.9 ± 26.3 a | 73.0 ± 23.1 a | 18.7 ± 5.1 a | 23.3 ± 10.2 b | 41.8 ± 12.2 a | 66.7 ± 6.4 b | |

| Isolates | Stage | Pileus Color | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | ||

| KMCC 01257 | C1 | 34.6 ± 3.0 b | 5.7 ± 0.3 c | 8.1 ± 1.1 c |

| C2 | 40.0 ± 16.1 a | 6.9 ± 2.9 b | 11.1 ± 4.3 b | |

| C3 | 36.7 ± 11.1 b | 8.0 ± 2.2 a | 12.5 ± 3.5 a | |

| KMCC 05164 | C1 | 34.9 ± 9.1 c | 4.2 ± 1.0 a | 8.5 ± 2.8 c |

| C2 | 47.6 ± 15.8 a | 3.5 ± 1.1 b | 12.6 ± 4.1 a | |

| C3 | 41.3 ± 12.5 b | 4.0 ± 1.0 ab | 11.5 ± 3.3 b | |

| PA-054 | C1 | 27.7 ± 3.9 c | 4.9 ± 0.8 c | 5.6 ± 1.5 c |

| C2 | 37.0 ± 16.0 a | 5.4 ± 1.3 b | 10.2 ± 5.1 a | |

| C3 | 35.1 ± 9.0 b | 6.5 ± 2.3 a | 10.3 ± 2.7 a | |

| PA-104 | C1 | 45.8 ± 9.5 a | 6.3 ± 0.8 a | 11.3 ± 2.8 a |

| C2 | 36.6 ± 13.8 c | 5.6 ± 2.0 b | 8.1 ± 3.3 c | |

| C3 | 41.0 ± 11.6 b | 6.5 ± 1.9 a | 10.9 ± 3.3 b | |

| PA-122 | C1 | 31.8 ± 9.9 b | 4.4 ± 2.3 b | 8.3 ± 3.9 b |

| C2 | 39.1 ± 17.0 a | 4.6 ± 2.6 a | 10.5 ± 5.5 a | |

| C3 | 28.1 ± 12.8 c | 3.1 ± 1.7 c | 6.5 ± 4.2 c | |

| PA-132 | C1 | 34.3 ± 6.9 c | 5.7 ± 1.6 a | 10.3 ± 2.6 b |

| C2 | 39.4 ± 15.7 a | 5.4 ± 2.0 ab | 11.7 ± 4.1 a | |

| C3 | 37.7 ± 12.9 b | 5.0 ± 1.6 b | 11.8 ± 3.8 a | |

| Isolate | σ2e* | σ2g | σ2p | Hbs | Criteria Hbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMCC 01257 | 271.5 | 6.42 | 277.92 | 0.024 | Very Low |

| KMCC 05164 | 70.09 | 6.07 | 76.16 | 0.080 | Low |

| PA-054 | 380.23 | 34.29 | 414.52 | 0.083 | Low |

| PA-104 | 323.88 | 49.31 | 373.19 | 0.132 | Low |

| PA-122 | 146.03 | 112.42 | 258.45 | 0.435 | Moderate |

| PA-132 | 14.83 | 43.76 | 58.59 | 0.746 | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Woo, S.-I.; Oh, M.; Lee, H.H.; Song, I.; Kim, S.J.; Oh, Y.-L.; Im, J.-H.; Lee, E.-J.; Lee, M.K. Development of Hybrid Pleurotus cystidiosus Strains with Enhanced Functional Properties. Foods 2025, 14, 4329. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244329

Woo S-I, Oh M, Lee HH, Song I, Kim SJ, Oh Y-L, Im J-H, Lee E-J, Lee MK. Development of Hybrid Pleurotus cystidiosus Strains with Enhanced Functional Properties. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4329. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244329

Chicago/Turabian StyleWoo, Sung-I, Minji Oh, Hak Hyun Lee, Inseo Song, Se Jeong Kim, Youn-Lee Oh, Ji-Hoon Im, Eun-Ji Lee, and Mi Kyeong Lee. 2025. "Development of Hybrid Pleurotus cystidiosus Strains with Enhanced Functional Properties" Foods 14, no. 24: 4329. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244329

APA StyleWoo, S.-I., Oh, M., Lee, H. H., Song, I., Kim, S. J., Oh, Y.-L., Im, J.-H., Lee, E.-J., & Lee, M. K. (2025). Development of Hybrid Pleurotus cystidiosus Strains with Enhanced Functional Properties. Foods, 14(24), 4329. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244329