Eurotium cristatum Ameliorates Glucolipid Metabolic Dysfunction of Obese Mice in Association with Regulating Intestinal Gluconeogenesis and Microbiome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Animal Experimentation

2.3. Biochemical Measurements

2.4. Histopathological Examination and Immunofluorescence

2.5. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) and Insulin Sensitivity Test (ITT)

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

2.7. Gut Microbiota Analysis

2.8. Analysis of SCFAs and Succinate in Colonic Contents

2.9. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

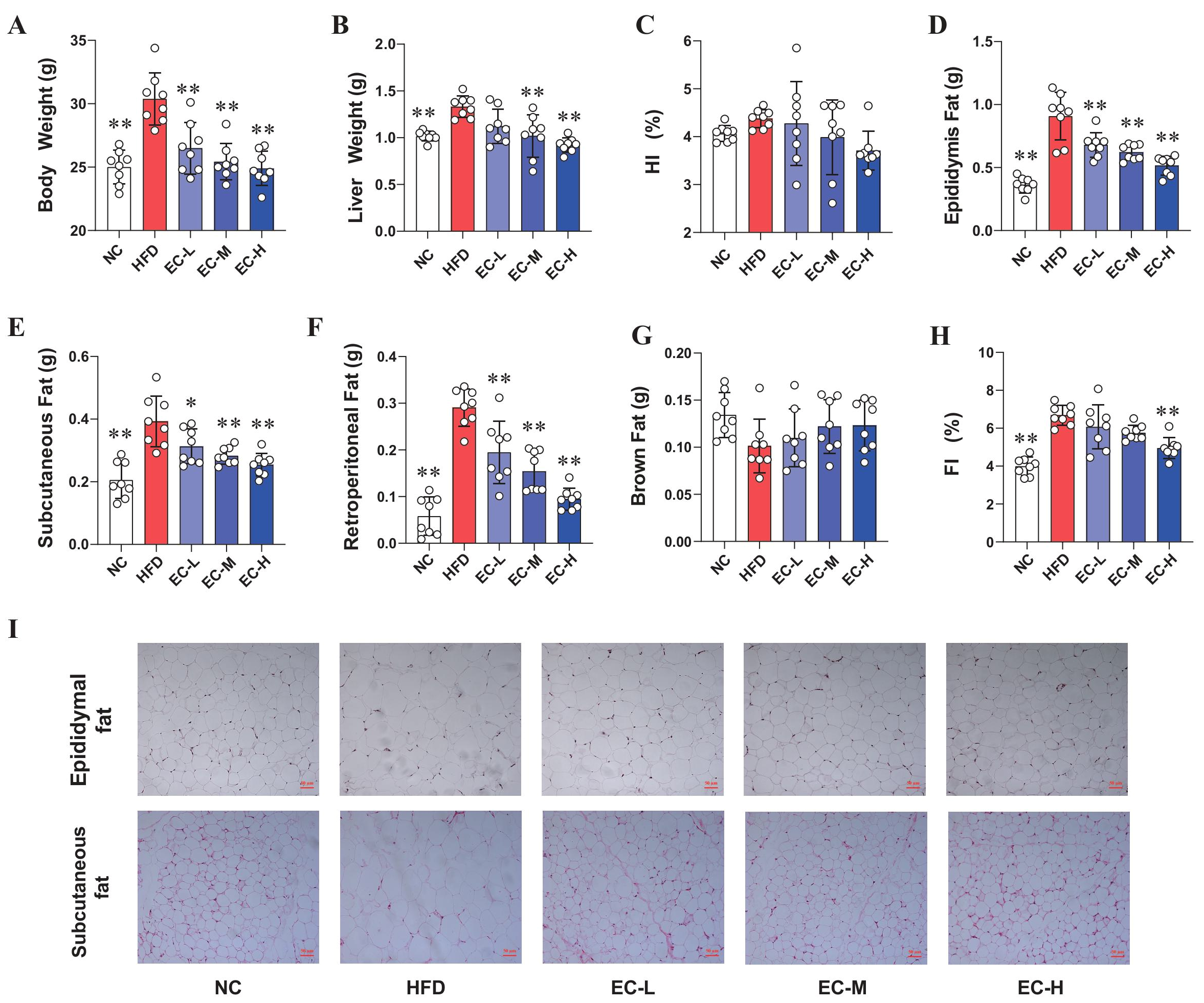

3.1. EC Inhibited Obesity in HFD Mice

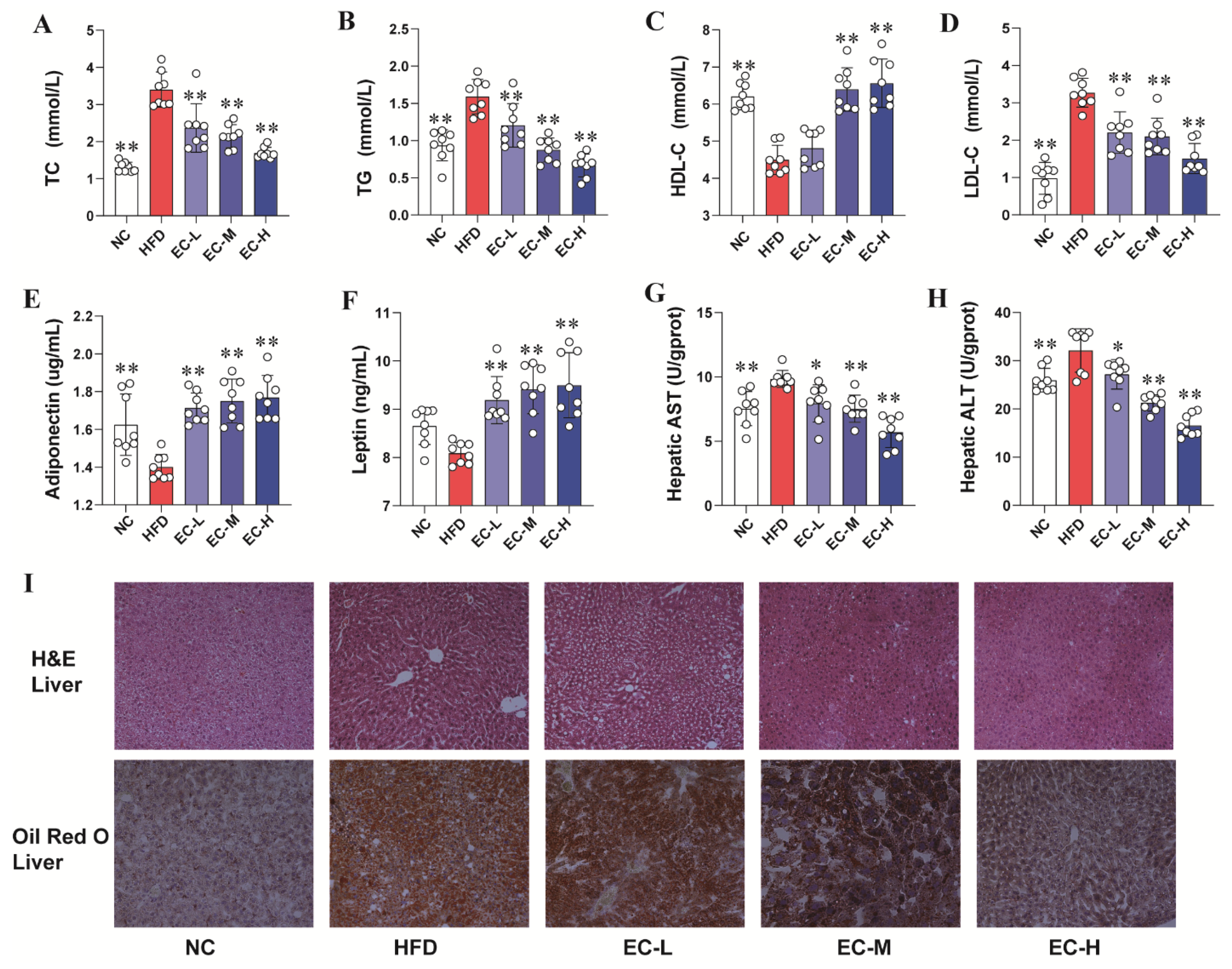

3.2. EC Alleviated Abnormal Glucolipid Metabolism and Liver Injury While Regulating Glucose Homeostasis in HFD Mice

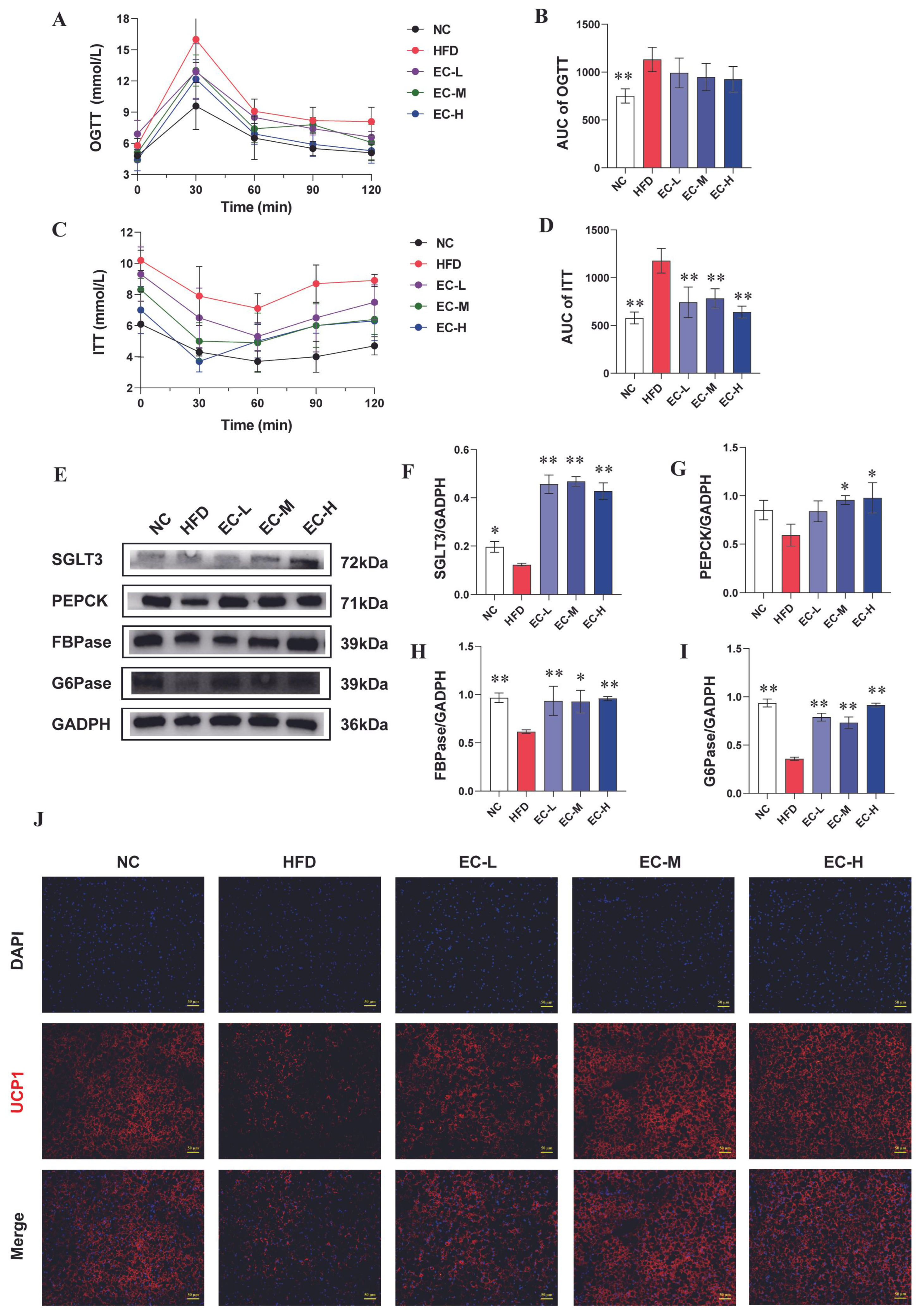

3.3. EC Activated Intestinal Gluconeogenesis (IGN) and Adipose Thermogenesis

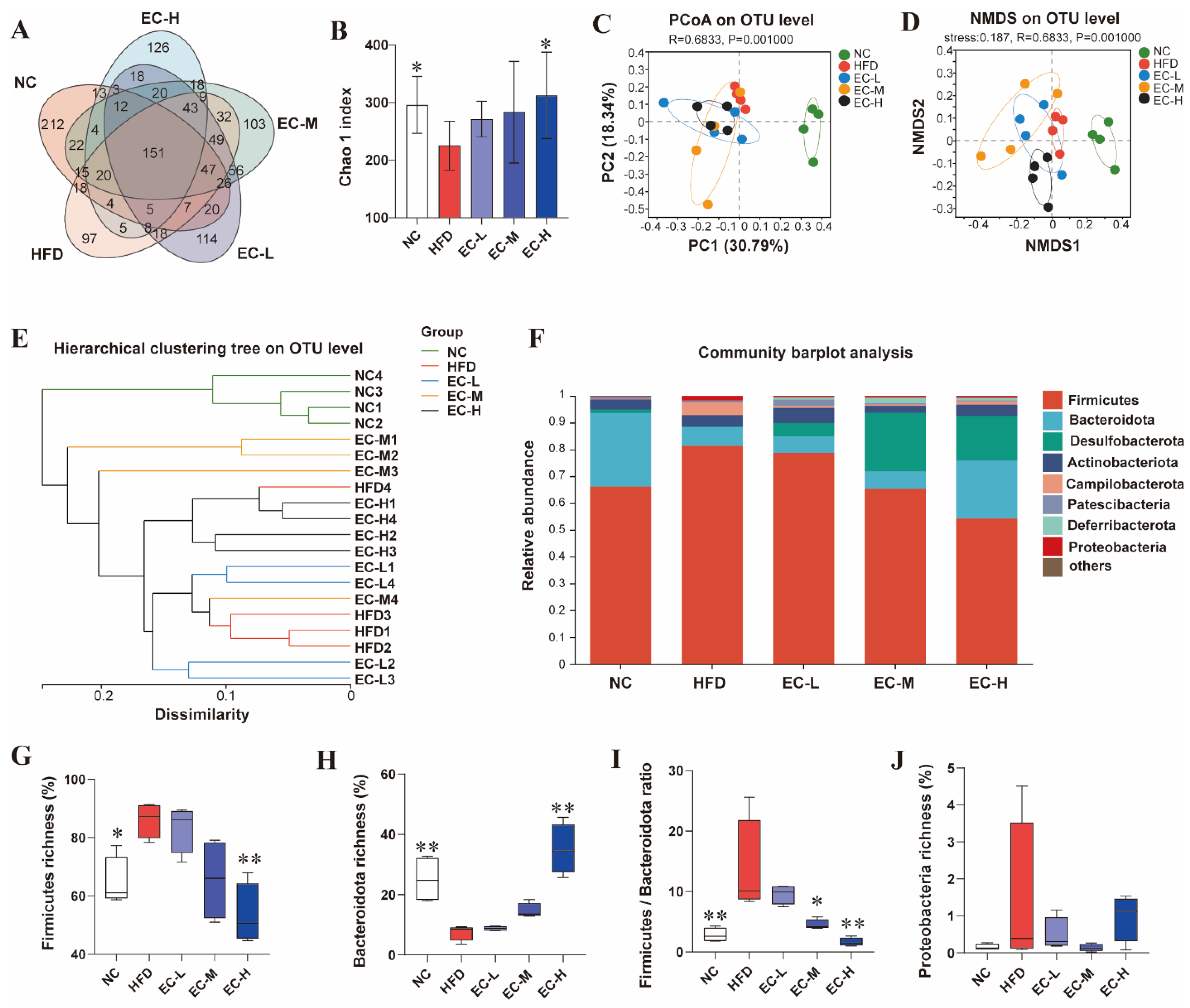

3.4. EC Reshaped the Gut Microbiota Composition of HFD Mice

3.5. EC Promotes Colonic SCFAs and Succinate Production and Alleviates Linoleic Acid Metabolism Dysregulation in HFD-Fed Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prado, C.M.; Batsis, J.A.; Donini, L.M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Siervo, M. Sarcopenic Obesity in Older Adults: A Clinical Overview. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, M.R.; Romero-Lado, M.J.; Carrasquilla, G.D.; Kilpeläinen, T.O. The Differential Impact of Abdominal Obesity on Fasting and Non-fasting Triglycerides and Cardiovascular Risk. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 17, zwaf058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingvay, I.; Cohen, R.; le Roux, C.W.; Sumithran, P. Obesity in Adults. Lancet 2024, 404, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.C.; Smith, G.I.; Palacios, H.H.; Farabi, S.S.; Yoshino, M.; Yoshino, J.; Cho, K.V.; Davila-Roman, V.G.; Shankaran, M.; Barve, R.A.; et al. Cardiometabolic Characteristics of People with Metabolically Healthy and Unhealthy Obesity. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Ianiro, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Adolph, T.E. Adipokines: Masterminds of Metabolic Inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 25, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, F.; He, X.; Huang, K. Plant Derived Exosome-Like Nanoparticles and Their Therapeutic Applications in Glucolipid Metabolism Diseases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 6385–6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Dilixiati, Y.; Xiao, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Z. Different Short-Chain Fatty Acids Unequally Modulate Intestinal Homeostasis and Reverse Obesity-Related Symptoms in Lead-Exposed High-Fat Diet Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 18971–18985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. A Metagenome-Wide Association Study of Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremaroli, V.; Backhed, F. Functional Interactions Between the Gut Microbiota and Host Metabolism. Nature 2012, 489, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, D.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Lyu, F. Effect and Mechanism of Insoluble Dietary Fiber on Postprandial Blood Sugar Regulation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 146, 104354–104363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Goncalves, D.; Vinera, J.; Zitoun, C.; Duchampt, A.; Backhed, F.; Mithieux, G. Microbiota-Generated Metabolites Promote Metabolic Benefits via Gut-brain Neural Circuits. Cell 2014, 156, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Liao, M.; Zhou, N.; Bao, L.; Ma, K.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; et al. Parabacteroides distasonis Alleviates Obesity and Metabolic Dysfunctions via Production of Succinate and Secondary Bile Acids. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Zitoun, C.; Duchampt, A.; Backhed, F.; Mithieux, G. Microbiota-Produced Succinate Improves Glucose Homeostasis via Intestinal Gluconeogenesis. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Li, S.; Yan, Q.; Huo, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A Genomic Compendium of Cultivated Human Gut Fungi Characterizes the Gut Mycobiome and Its Relevance to Common Diseases. Cell 2024, 187, 2969–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, W.; Kang, M.; Quan, W.; Qiu, G.; Tao, T.; Li, C.; Zhu, S.; Lu, B.; Liu, Z. Soluble Dietary Fiber from Fermentation of Tea Residues by Eurotium cristatum and the Effects on DSS-induced Ulcerative Colitis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 15717–15732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Lei, L.; Li, X.; Hu, W.; Zhang, T.; Yang, W.; Ma, B.; Si, S.; Xu, Y.; Yu, L. Secondary Metabolites Produced by the Dominant Fungus Eurotium cristatum in Liupao Tea and Their Hypolipidemic Activities by Regulating Liver Lipid Metabolism and Remodeling Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 27978–27990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.C.; Weir, T.L.; Broeckling, C.D.; Ryan, E.P. Antibacterial Activity and Phytochemical Profile of Fermented Camellia sinensis (Fuzhuan tea). Food Res. Int. 2013, 53, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, L.; Yao, H.; Wang, J.; An, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z. Unraveling the Unique Profile of Fu Brick Tea: Volatile Components, Analytical Approaches and Metabolic Mechanisms of Key Odor-Active Compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 156, 104879–104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhao, T.; Shao, H.; Ren, D.; Yang, X. Nonextractable Polyphenols from Fu Brick Tea Alleviates Ulcerative Colitis by Controlling Colon Microbiota-targeted Release to Inhibit Intestinal Inflammation in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 7397–7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhen, Q.; Liang, Q.; Bian, C.; Sun, W.; Lv, H.; Tian, C.; Zhao, X.; Guo, X. Roles of Gut Microbiota Metabolites and Circadian Genes in the Improvement of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in KKAy Mice by Theabrownin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 5260–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, R.; Lauss, M.; Sanna, A.; Donia, M.; Larsen, M.S.; Mitra, S.; Johansson, I.; Phung, B.; Harbst, K.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; et al. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures Improve Immunotherapy and Survival in Melanoma. Nature 2020, 577, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, C.; Wu, X.; Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiao, X.; Li, J.; Han, L.; Wang, M. Protocatechuic Acid Suppresses Lipid Uptake and Synthesis Through the PPARγ Pathway in High-fat Diet-induced NAFLD Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 4012–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Qi, Z.; Wang, G.; Wu, C.; Mumby, W.; Huang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Sun, Q. Permethrin Stimulates Fat Accumulation via Regulating Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 21352–21362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De la Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; Julieta Gonzalez, M.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1486–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ren, D.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Yang, X. Intracellular Polysaccharides of Eurotium cristatum Exhibited Anticolitis Effects in Association with Gut Tryptophan Metabolism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 16347–16358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, R.; Yang, X.; Fang, C.; Yao, L.; Lv, J.; Wang, L.; Shi, M.; Zhang, W.; et al. Effects of Prevotella copri on Insulin, Gut Microbiota and Bile Acids. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2340487–2340499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Krisnawati, D.I.; Susilowati, E.; Mutalik, C.; Kuo, T.R. Next-generation Probiotics and Chronic Diseases: A Review of Current Research and Future Directions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 27679–27700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Hussain, N.; Hameed, Z.; Lin, L. Elucidating the Role of Diet in Maintaining Gut Health to Reduce the Risk of Obesity, Cardiovascular and Other Age-related Inflammatory Diseases: Recent Challenges and Future Recommendations. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2297864–2297895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, A.; Du, H.; Liu, Y.; Qi, B.; Yang, X. Theabrownin from Fu Brick Tea Exhibits the Thermogenic Function of Adipocytes in High-fat Diet-induced Obesity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11900–11911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Shi, L.; Wang, Q.; Yan, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X. Fu Brick Tea Polysaccharides Prevent Obesity via Gut Microbiota-controlled Promotion of Adipocyte Browning and Thermogenesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 13893–13903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, M.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Z. Structural Characterization of Eurotium cristatum Spore Polysaccharide and Its Hypoglycemic and Hypolipidemic Ability in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142296–142308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, S.M.; Feeney, R.H.; Prasoodanan, P.K.V.; Puertolas-Balint, F.; Singh, D.K.; Wongkuna, S.; Zandbergen, L.; Hauner, H.; Brandl, B.; Nieminen, A.I.; et al. The Gut Commensal Blautia Maintains Colonic Mucus Function Under Low-fiber Consumption Through Secretion of Short-chain Fatty Acids. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3502–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Cheng, X.; Shen, L.; Liu, Z.; Ye, X.; Yan, Z.; Wei, W.; Wang, X. Novel Human Milk Fat Substitutes Based on Medium- and Long-chain Triacylglycerol Regulate Thermogenesis, Lipid Metabolism, and Gut Microbiota Diversity in C57BL/6J Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 6213–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Luo, L.; Wang, S.; Guan, X. Polyphenolic Extracts of Coffee Cherry Husks Alleviated Colitis-induced Neural Inflammation via NF-κB Signaling Regulation and Gut Microbiota Modification. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6467–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; O’Morain, C.A.; Gisbert, J.P.; Kuipers, E.J.; Axon, A.T.; Bazzoli, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Atherton, J.; Graham, D.Y.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori Infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2017, 66, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, L. Maternal Phlorizin Intake Protects Offspring from Maternal Obesity-induced Metabolic Disorders in Mice via Targeting Gut Microbiota to Activate the SCFA-GPR43 Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 4703–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, B. Chlorogenic Acid/Linoleic Acid-fortified Wheat-Resistant Starch Ameliorates High-fat Diet-induced Gut Barrier Damage by Modulating Gut Metabolism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 11759–11772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Z.; Lu, Z.; Li, Q.; Tong, W. Intestinal Glucose Excretion: A Potential Mechanism for Glycemic Control. Metabolism 2024, 152, 155743–155752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Fang, J.; Zhang, W.; Chan, K.; Chan, Y.; Dong, C.; Li, S.; Lyu, A.; Xu, J. Dissecting the Anti-obesity Components of Ginseng: How Ginseng Polysaccharides and Ginsenosides Target Gut Microbiota to Suppress High-fat Diet-induced Obesity. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 75, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davico, B.; Martin, M.; Condori, A.I.; Chiappe, E.L.; Gaete, L.; Tetzlaff, W.F.; Yanez, A.; Osta, V.; Saez, M.S.; Bava, A.; et al. Fatty acids in Childhood Obesity: A Link Between Nutrition, Metabolic Alterations and Cardiovascular Risk. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2025, 14, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, W.; Han, N.; Zhang, X. Eurotium cristatum Ameliorates Glucolipid Metabolic Dysfunction of Obese Mice in Association with Regulating Intestinal Gluconeogenesis and Microbiome. Foods 2025, 14, 4273. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244273

Yang W, Han N, Zhang X. Eurotium cristatum Ameliorates Glucolipid Metabolic Dysfunction of Obese Mice in Association with Regulating Intestinal Gluconeogenesis and Microbiome. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4273. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244273

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Weirong, Ning Han, and Xiangnan Zhang. 2025. "Eurotium cristatum Ameliorates Glucolipid Metabolic Dysfunction of Obese Mice in Association with Regulating Intestinal Gluconeogenesis and Microbiome" Foods 14, no. 24: 4273. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244273

APA StyleYang, W., Han, N., & Zhang, X. (2025). Eurotium cristatum Ameliorates Glucolipid Metabolic Dysfunction of Obese Mice in Association with Regulating Intestinal Gluconeogenesis and Microbiome. Foods, 14(24), 4273. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244273