Co-Fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pichia pastoris: A Novel Approach to Enhance Flavor and Quality of Fermented Tea Beverage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Fermented Tea Beverage Preparation

2.3. Determination of Dynamic Changes in Physicochemical Properties

2.3.1. Determination of Viable Count

2.3.2. Determination of pH, Reducing Sugars, Titratable Acidity, and Total Esters

2.4. Determination of Alcohol Content

2.5. Determination of Antioxidant Properties

2.6. Determination of Organic Acids

2.7. Sensory Evaluation

2.8. Determination of Volatile Compounds Using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

2.9. Determination of Microbial Diversity

2.10. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dynamic Changes Analysis of Fermentation Process

3.1.1. Changes in Viable Counts During Fermentation Process

3.1.2. Changes in pH and Titratable Acidity During Fermentation Process

3.1.3. Changes in Total Esters and Reducing Sugars During Fermentation Process

3.2. Analysis of Changes in Antioxidant Properties

3.3. Analysis of Changes in Alcohol Content

3.4. Analysis of Changes in Organic Acid

3.5. Analysis of the Sensory Evaluation

3.6. Analysis of the Volatile Compounds

3.7. Analysis of Microbial Diversity and Composition in FTB

3.7.1. Analysis of Bacterial Diversity and Composition

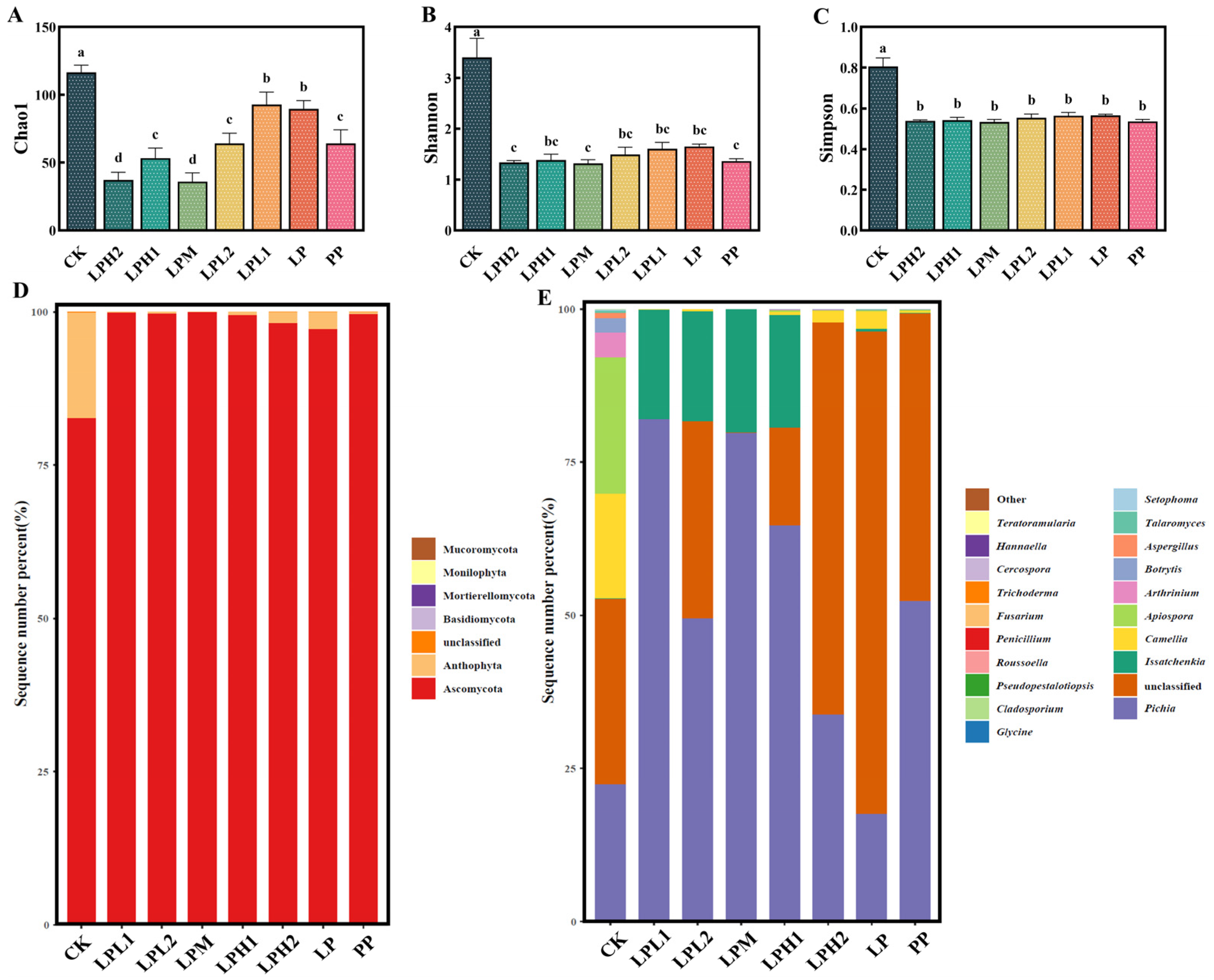

3.7.2. Analysis of Fungal Diversity and Composition

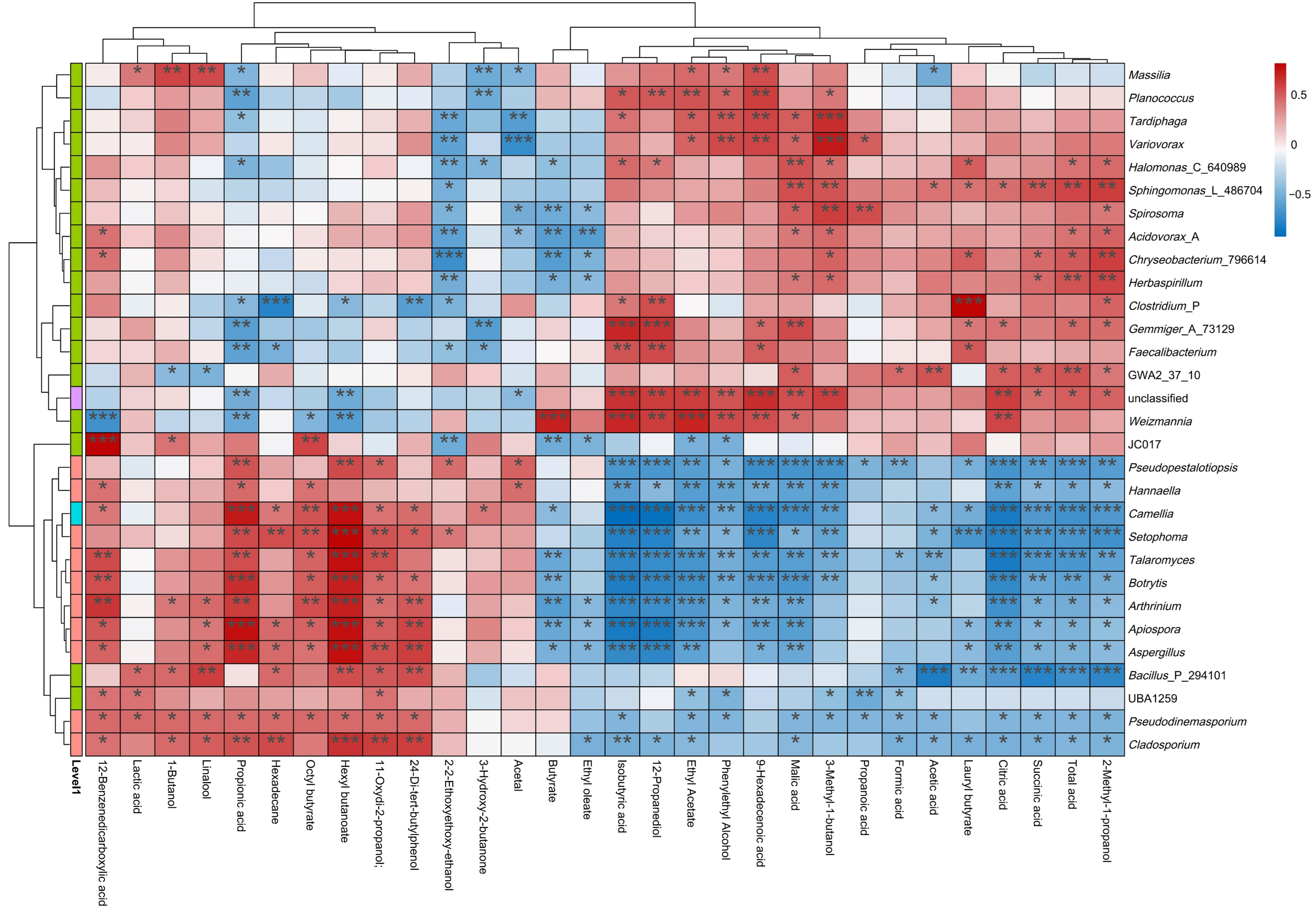

3.8. Correlation of FTB Flavor Characteristic Metabolites and Active Microflora

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, Z.; Chi-Tang, H.; Jie, Z.; Santos, J.S.; Armstrong, L.; Granato, D. Chemistry and biological activities of processed Camellia sinensis teas: A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1474–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Granato, D.; Zou, C.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yin, J.-F.; Zhou, W.; Xu, Y.-Q. Processing technologies for manufacturing tea beverages: From traditional to advanced hybrid processes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ma, W.L.; Hu, S.N.; Qian, Z.Y.; Shen, C.; Mao, J. Neuroprotective effects of Chinese rice wine fermented with Fu Brick Tea on H2O2-induced PC12 Cells. FASEB J. 2021, 35, 01966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, L.; Tunyaluk, B.; Li, P. Dynamic changes in volatile components during dark tea wine processing. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 194, 115783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Qin, Y.; Pathirana, S.; Araujo, L.D.; Culley, N.J.; Kilmartin, P.A. Effects of post-fermentation addition of green tea extract for sulfur dioxide replacement on Sauvignon Blanc wine phenolic composition, antioxidant capacity, colour, and mouthfeel attributes. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Gao, Y.; Fu, Y.-Q.; Chen, J.-X.; Yin, J.-F.; Xu, Y.-Q. Innovative technologies in tea-beverage processing for quality improvement. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 47, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Bian, C.; Zhao, L.-L.; Chen, Q.; Bi, H.-J.; Yang, X.-H.; et al. Enhancement of ester biosynthesis in blueberry wines through co-fermentation via cell–cell contact between Torulaspora delbrueckii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Res. Int. 2024, 179, 114029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fan, G.; Peng, Y.; Xu, N.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liang, H.; Zhan, J.; Huang, W.; You, Y. Mechanisms and effects of non-Saccharomyces yeast fermentation on the aromatic profile of wine. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 124, 105660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-y.; Yao, Q.-b.; Jia, X.-z.; Chen, B.-r.; Abdul, R.; Wang, L.-h.; Zeng, X.-a.; Liu, D.-m. Characterization and application in yogurt of genipin-crosslinked chitosan microcapsules encapsulating with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum DMDL 9010. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-y.; Huang, F.; Huang, J.-y.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.-n.; Yao, Q.-b.; Zeng, X.-a.; Chen, B.-r. Repercussions of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HYY-DB9 and Levilactobacillus brevis GIM 1.773 on the degradation of nitrite, volatile compounds, and sensory assessment of traditional Chinese paocai. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 6522–6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Shah, N.P. Lactic acid bacterial fermentation modified phenolic composition in tea extracts and enhanced their antioxidant activity and cellular uptake of phenolic compounds following in vitro digestion. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 20, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, X.; Youyi, H.; Wenpeng, Y.; Bowei, Z.; Xiaoxia, Q. Screening lactic acid bacteria with high yielding-acid capacity from pickled tea for their potential uses of inoculating to ferment tea products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6727–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jiang, J.; Yin, R.; Xie, Y.; Ma, X.; Cui, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Niu, J.; Cheng, W.; et al. Effects of cofermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and different lactic acid bacteria on the organic acid content, soluble sugar content, biogenic amines, phenol content, antioxidant activity and aroma of prune wine. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, D.; Ren, L.; Song, S.; Ma, X.; Rong, Y. Effects of simultaneous and sequential cofermentation of Wickerhamomyces anomalus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on physicochemical and flavor properties of rice wine. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-y.; Jia, X.-z.; Yu, J.-j.; Chen, Y.-h.; Liu, D.-m.; Liang, M.-h. Effect of different lactic acid bacteria on nitrite degradation, volatile profiles, and sensory quality in Chinese traditional paocai. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 147, 111597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Hai, H.; Sun, D.; Yuan, W.; Liu, W.; Ding, R.; Teng, M.; Ma, L.; Tian, J.; Chen, C. A high throughput method for total alcohol determination in fermentation broths. BMC Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Peng, Q.; Yang, H.; Hu, B.; Shen, C.; Tian, R. Influence of different carbohydrate sources on physicochemical properties and metabolites of fermented greengage (Prunus mume) wines. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 121, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Zhu, B.; Liu, R.; Gao, Q.; Lin, G.; Wu, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, B. Comparison of volatile composition and color attributes of mulberry wine fermented by different commercial yeasts. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, J.; Burger, R.; Schulze, M. Statistical evaluation of DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and Folin-Ciocalteu assays to assess the antioxidant capacity of lignins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.S.; Furtado, I.; Bastos, M.d.L.; de Pinho, P.G.; Pinto, J. The influence of different closures on volatile composition of a white wine. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 23, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Mitchell, A.L.; Tarkowska, A.; Finn, R.D. Benchmarking taxonomic assignments based on 16S rRNA gene profiling of the microbiota from commonly sampled environments. Gigascience 2018, 7, giy054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2′s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Oliveira, R.P.; Perego, P.; De Oliveira, M.N.; Converti, A. Effect of inulin as a prebiotic to improve growth and counts of a probiotic cocktail in fermented skim milk. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontoin, H.; Saucier, C.; Teissedre, P.-L.; Glories, Y. Effect of pH, ethanol and acidity on astringency and bitterness of grape seed tannin oligomers in model wine solution. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hu, W.; Jiang, A.; Xiu, Z.; Ji, Y.; Guan, Y.; Sarengaowa; Yang, X. Effect of salt concentration on quality of Chinese northeast sauerkraut fermented by Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Biosci. 2019, 30, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, L.; Foo, H.L.; Cao, Z.; Lin, Q. Changes in microbial diversity and volatile metabolites during the fermentation of Bulang pickled tea. Food Chem. 2024, 458, 140293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-y.; Yu, J.-j.; Zhou, Q.-y.; Sun, L.-n.; Liu, D.-m.; Liang, M.-h. Preparation of yogurt-flavored bases by mixed lactic acid bacteria with the addition of lipase. LWT 2020, 131, 109577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, T.; Perestrelo, R.; Bordiga, M.; Locatelli, M.; Coïsson, J.D.; Câmara, J.S. The flavor chemistry of fortified wines—A comprehensive approach. Foods 2021, 10, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, X.; Jia, W.; Wen, B.; Liao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, Q.; Li, K.; Hua, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Dynamic changes in the major chemical and volatile components during the “Ziyan” tea wine processing. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 186, 115273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorello, F.; Jose Valera, M.; Martin, V.; Parada, A.; Salzman, V.; Camesasca, L.; Farina, L.; Boido, E.; Medina, K.; Dellacassa, E.; et al. Genomic and transcriptomic basis of Hanseniaspora vineae’s impact on flavor diversity and wine quality. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01959-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Guo, T.; Lu, Y.; Hadiatullah, H.; Li, P.; Ding, K.; Zhao, G. Effects of amino acid composition of yeast extract on the microbiota and aroma quality of fermented soy sauce. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, T.; Wang, D.; Jin, R.L.; Zhang, H.P.; Zhou, T.T.; Sung, T.S. Characterization of volatile compounds in fermented milk using solid-phase microextraction methods coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 2488–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdis, C.; Sumby, K.; Bartowsky, E.; Jiranek, V. Lactic acid bacteria in wine: Technological advances and evaluation of their functional role. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 612118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, E.J.; Teixeira, J.A.; Brányik, T.; Vicente, A.A. Yeast: The soul of beer’s aroma—A review of flavour-active esters and higher alcohols produced by the brewing yeast. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G. Lactic metabolism revisited: Metabolism of lactic acid bacteria in food fermentations and food spoilage. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.-J.; Song, L.; Han, Y.; Zhen, P.; Han, D.-Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, X.; Wei, Y.-H.; Yu, H.-X.; Han, P.-J.; et al. Microbial communities and their correlation with flavor compound formation during the mechanized production of light-flavor Baijiu. Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Li, Z. Polysaccharides isolated from Nostoc commune Vaucher inhibit colitis-associated colon tumorigenesis in mice and modulate gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 6873–6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, L.; Yin, J.; Ma, N.; Tao, Y. Adjustment of impact odorants in Hutai-8 rose wine by co-fermentation of Pichia fermentans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Res. Int. 2022, 153, 110959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, D.; Mu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Qi, Q.; Mu, Y.; Su, W. Exploring the heterogeneity of community and function and correspondence of “species-enzymes” among three types of Daqu with different fermentation peak-temperature via high-throughput sequencing and metagenomics. Food Res. Int. 2024, 176, 113805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archana, K.M.; Ravi, R.; Anu-Appaiah, K.A. Correlation between ethanol stress and cellular fatty acid composition of alcohol producing non-Saccharomyces in comparison with Saccharomyces cerevisiae by multivariate techniques. J. Food Sci. Technol. Mysore 2015, 52, 6770–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Yu, H.; Fu, X.; Li, Z.; Dong, W.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Qu, B.; Bi, X. Characterization of volatile compounds and microbial diversity of Arabica coffee in honey processing method based on different mucilage retention treatments. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredient | LPH2 | LPH1 | LPM | LPL1 | LPL2 | LP | PP | CK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutinous rice (g) | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Distilled water (mL) | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Amylase (g) | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Glucoamylase (g) | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Green tea leaves (g) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| L. plantarum (log CFU/mL) | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | - | - |

| P. pastoris (log CFU/mL) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | - | 6 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, F.; Liang, Y.-T.; Chen, W.-J.; Cai, Y.-H.; Wang, L.-H.; Huang, Y.-Y. Co-Fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pichia pastoris: A Novel Approach to Enhance Flavor and Quality of Fermented Tea Beverage. Foods 2025, 14, 4251. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244251

Li J, Chen Y, Huang F, Liang Y-T, Chen W-J, Cai Y-H, Wang L-H, Huang Y-Y. Co-Fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pichia pastoris: A Novel Approach to Enhance Flavor and Quality of Fermented Tea Beverage. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4251. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244251

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jian, Yan Chen, Fang Huang, Yan-Tong Liang, Wei-Jian Chen, Yi-Han Cai, Lang-Hong Wang, and Yan-Yan Huang. 2025. "Co-Fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pichia pastoris: A Novel Approach to Enhance Flavor and Quality of Fermented Tea Beverage" Foods 14, no. 24: 4251. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244251

APA StyleLi, J., Chen, Y., Huang, F., Liang, Y.-T., Chen, W.-J., Cai, Y.-H., Wang, L.-H., & Huang, Y.-Y. (2025). Co-Fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pichia pastoris: A Novel Approach to Enhance Flavor and Quality of Fermented Tea Beverage. Foods, 14(24), 4251. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244251