Toward Standardized Measurement of Active Phytohemagglutinin in Common Bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, L.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.1.1. Hemagglutination Reagents

2.1.2. ELISA Reagents

2.1.3. PAGE Reagents

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Sample Extract Homogenization and Centrifugation

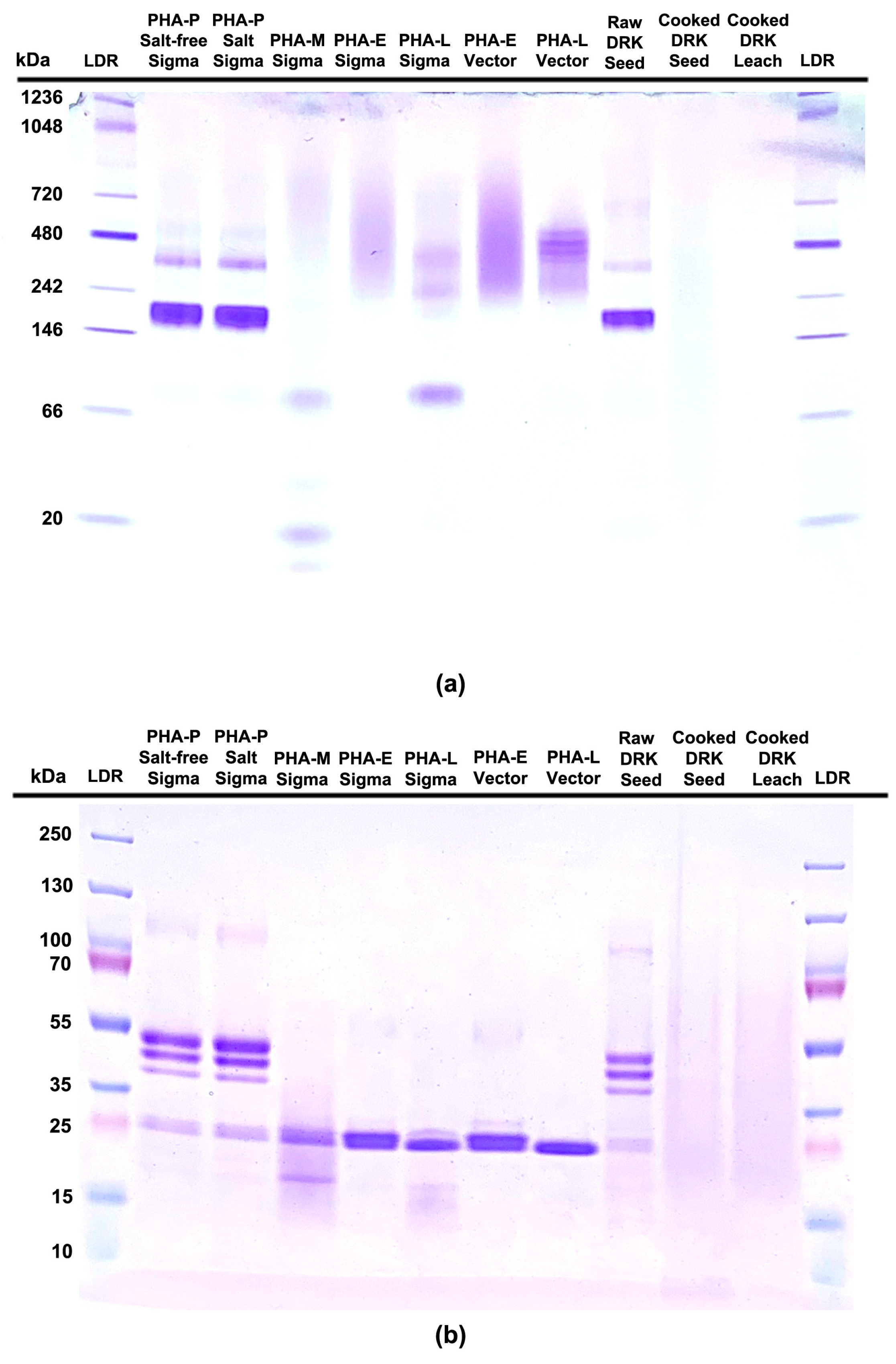

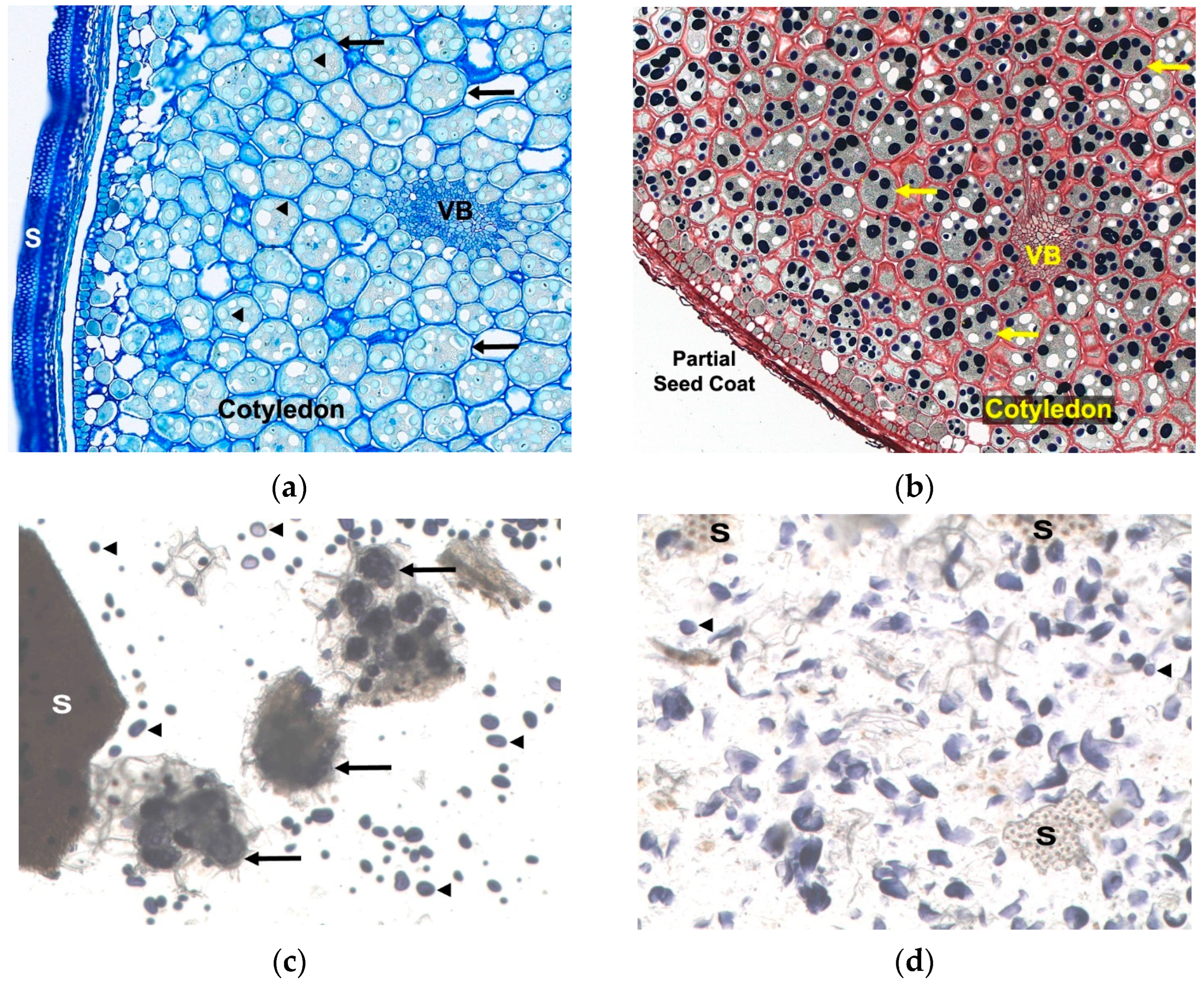

2.4. Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) to Assess Appropriate PHA Control

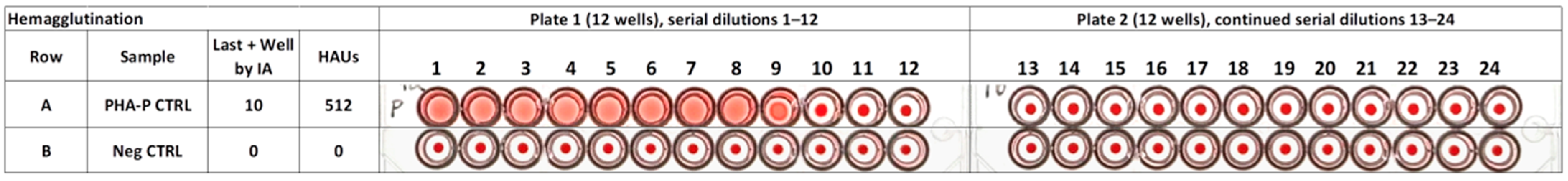

2.5. Hemagglutination Assay

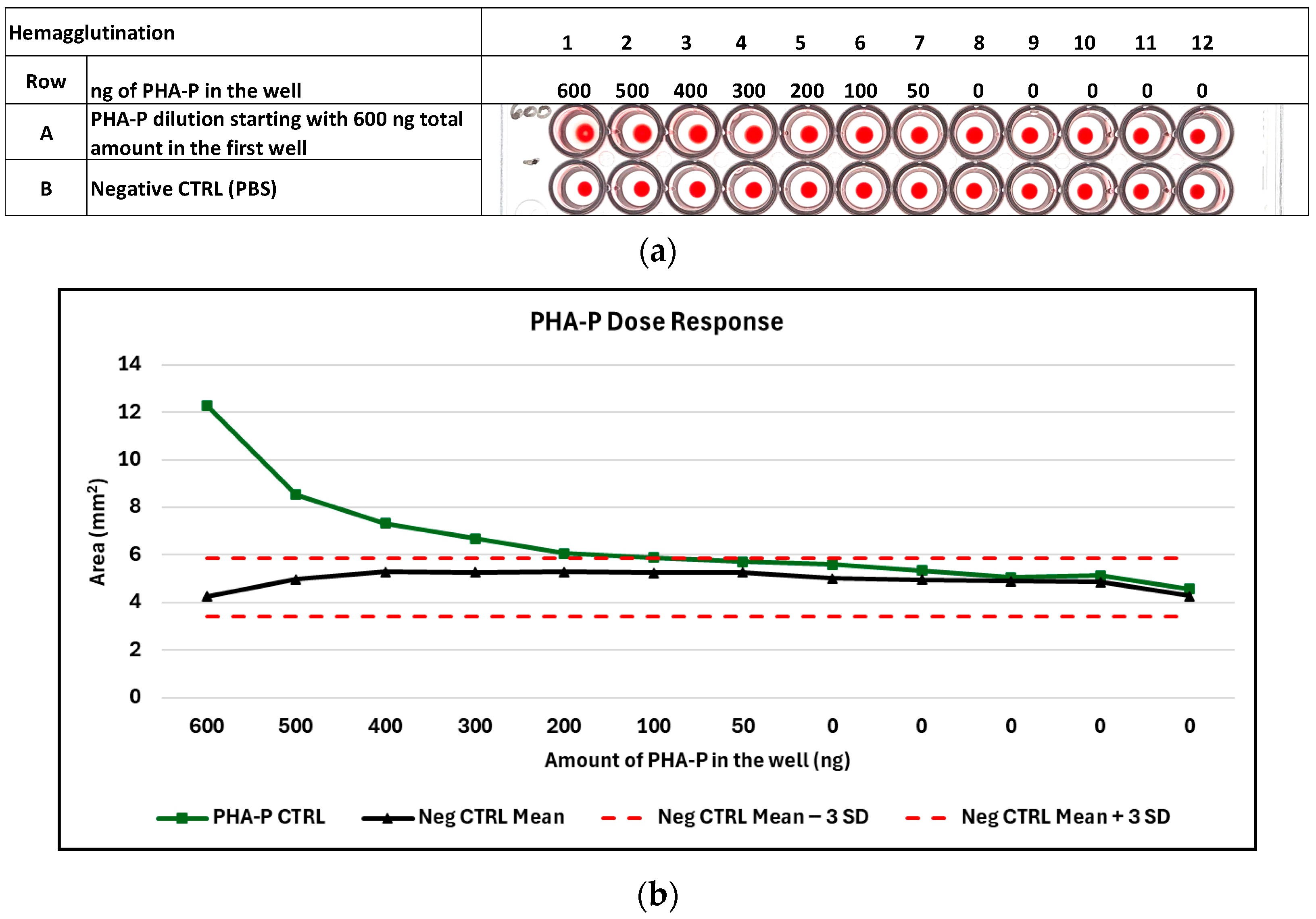

2.6. Image Analysis

2.7. ELISA Assay

3. Results

3.1. PHA Standard

3.2. Extraction and Centrifugation

Effect of Centrifugation Speed on Clarity of Sample Extracts

3.3. Analysis of PHA

3.3.1. Hemagglutination of Purified PHA-P

3.3.2. Estimated Amount of PHA-P Detectable by Hemagglutination Using the Digital Image Analysis Algorithm to Detect the Last Positive and First Negative Well

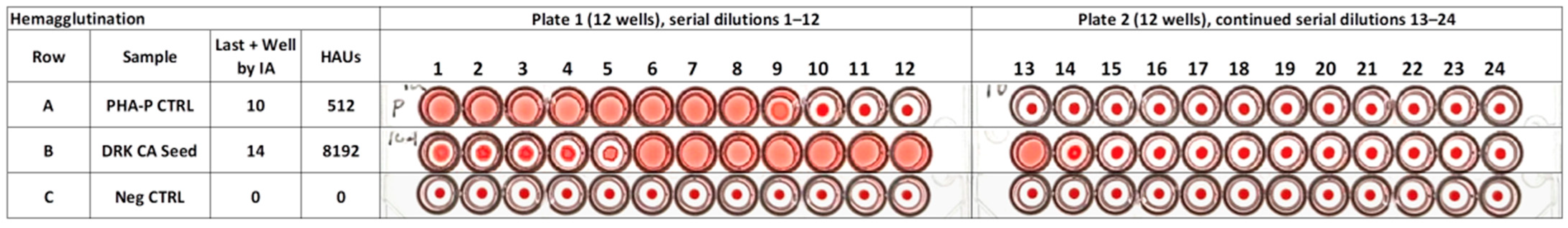

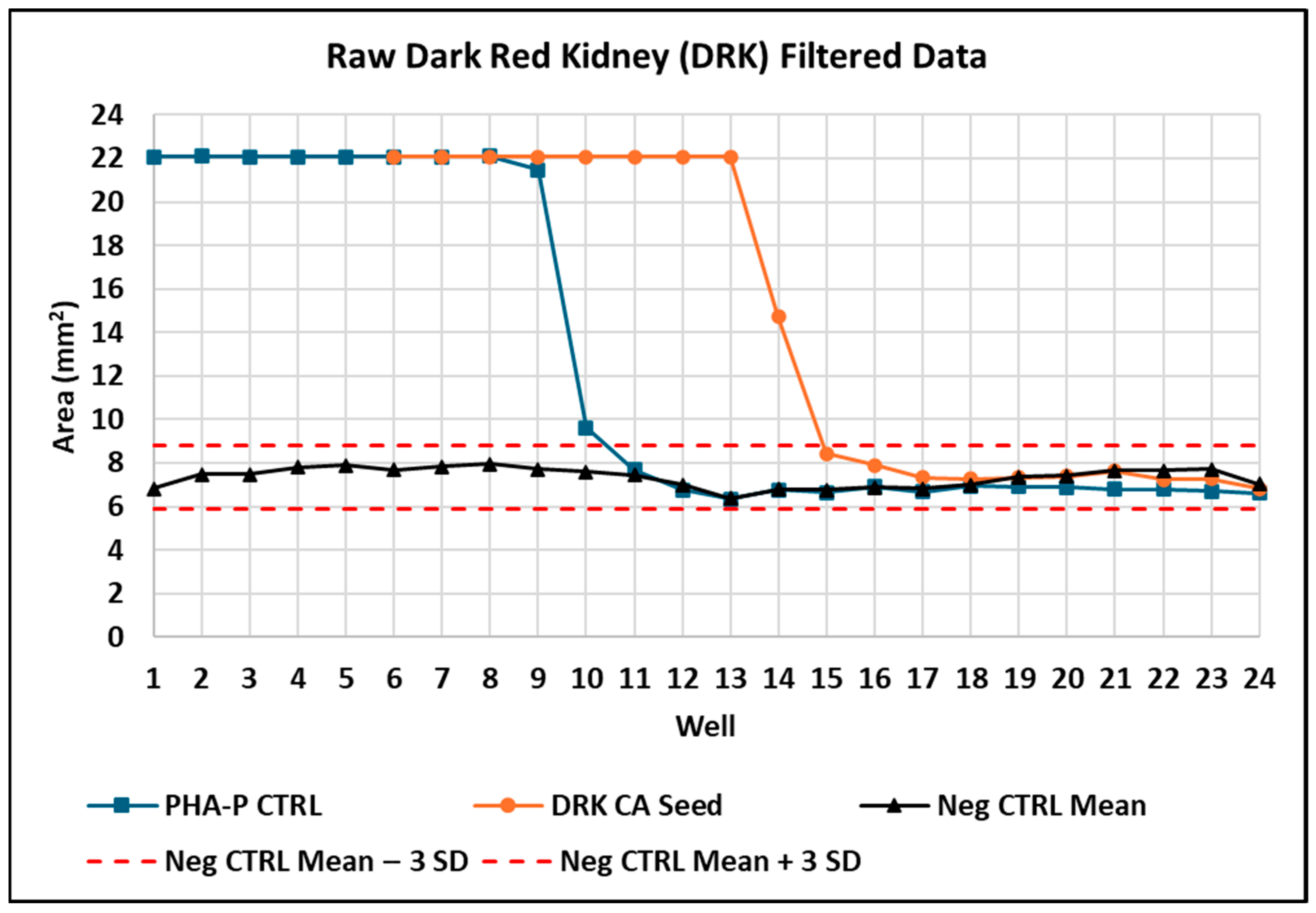

3.3.3. Hemagglutination of Raw DRK Bean Seed

3.4. ELISA

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

4.2. Sample Extraction

4.3. Positive Control/Standard: Selection and Preparation

4.4. Assessing PHA Using the Hemagglutination Assay

4.5. Assessing PHA Using an ELISA Assay

4.6. Application of the Proposed Methodology

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| DRK | Dark red kidney |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| HAU | Hemagglutination unit |

| PAGE | Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PBSB | Phosphate-buffered saline with bovine serum albumin |

| PBST | Phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 |

| PHA | Phytohemagglutinin |

| RBC | Red blood cell |

References

- Sathe, S.K. Dry Bean Protein Functionality. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2002, 22, 175–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, I.; Ahmad, A.; Masud, T.; Ahmed, A.; Bashir, S. Nutritional and Health Perspectives of Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): An Overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nciri, N.; Cho, N.; Mhamdi, F.E.; Ismail, H.B.; Mansour, A.B.; Sassi, F.H.; Aissa-Fennira, F.B. Toxicity Assessment of Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Widely Consumed by Tunisian Population. J. Med. Food 2015, 18, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Behura, A.; Mawatwal, S.; Kumar, A.; Naik, L.; Mohanty, S.S.; Manna, D.; Dokania, P.; Mishra, A.; Patra, S.K.; et al. Structure-function and application of plant lectins in disease biology and immunity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 134, 110827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, N.D.; Bender, A.E.; Reaidi, G.B.; Gilbert, R.J. Food poisoning from raw red kidney beans. Br. Med. J. 1980, 281, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodhouse, J.C.; Haugh, C.A.; Roberts, D.; Gilbert, R.J. Red kidney bean poisoning in the UK: An analysis of 50 suspected incidents between 1976 and 1989. Epidemiol. Infect. 1990, 105, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamcová, A.; Laursen, K.H.; Ballin, N.Z. Lectin Activity in Commonly Consumed Plant-Based Foods: Calling for Method Harmonization and Risk Assessment. Foods 2021, 10, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponskhe, K.; DuBois, A.; Towa, L.; Hooper, S.A.-O.; Cichy, K.; Mayhew, E.A.-O. Evaluating the Impact of Cultivar and Processing on Pulse Off-Flavor Through Descriptive Analysis, GC-MS, and E-Nose. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, N.; Lis, H. History of lectins: From hemagglutinins to biological recognition molecules. Glycobiology 2004, 14, 53r–62r. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsted, R.L.; Leavitt, R.D.; Chen, C.; Bachur, N.R.; Dale, R.M. Phytohemagglutinin isolectin subunit composition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1981, 668, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Chu, Z.; Ning, K.; Zhu, M.; Zhai, R.; Xu, P. A precise IDMS-based method for absolute quantification of phytohemagglutinin, a major antinutritional component in common bean. bioRxiv 2023. bioRxiv:2023.2012.2007.570538. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Fang, Z.; Yang, S.; Ning, K.; Xu, M.; Buhot, A.; Hou, Y.; Hu, P.; Xu, P. Innovations in measuring and mitigating phytohemagglutinins, a key food safety concern in beans. Food Qual. Saf. 2024, 8, fyae003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniglia, C.; Fedele, E.; Sanzini, E. Measurement by ELISA of Active Lectin in Dietary Supplements Containing Kidney Bean Protein. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 1283–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.; Moreira, S.I.; Assis, F.G.; Vicentini, S.N.C.; Silva, A.G.; Oliveira, T.Y.K.; Christiano, F.S.; Custódio, A.A.P.; Leite, R.P.; Gasparoto, M.C.G.; et al. An Accurate, Affordable, and Precise Resazurin-Based Digital Imaging Colorimetric Assay for the Assessment of Fungicide Sensitivity Status of Fungal Populations. Agronomy 2023, 13, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, E.J.M.; Rougé, P.; Peumans, W.J. 3.26—Plant Lectins. In Comprehensive Glycoscience; Kamerling, H., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 563–599. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, B.; Perrone, D.; Galasso, I.; Bollini, R. Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) lines devoid of major lectin proteins. Plant Breed. 2009, 128, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, D.G.; Uebersax, M.A.; Hosfield, G.L.; Brunner, J.R. Evaluation of the Hemagglutinating Activity of Low-Temperature Cooked Kidney Beans. J. Food Sci. 1985, 50, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nciri, N.; Cho, N.; El Mhamdi, F.; Ben Mansour, A.; Haj Sassi, F.; Ben Aissa-Fennira, F. Identification and Characterization of Phytohemagglutinins from White Kidney Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L., var. Beldia) in the Rat Small Intestine. J. Med. Food 2016, 19, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Abbaspourrad, A. How Much Bean Hemagglutinin Is Safe for Human Consumption? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6937–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarpazhooh, E.; Boye, J.I. Composition of Processed Dry Beans and Pulses. In Dry Beans and Pulses Production, Processing and Nutrition; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 101–128. [Google Scholar]

- Manen, J.F.; Pusztai, A. Immunocytochemical localisation of lectins in cells of Phaseolus vulgaris L. seeds. Planta 1982, 155, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, T.J.; Christie, J.; Wilson, A.; Ziegler, T.R.; Methe, B.; Flanders, W.D.; Rolls, B.J.; Loye Eberhart, B.; Li, J.V.; Huneault, H.; et al. Fibre-rich Foods to Treat Obesity and Prevent Colon Cancer trial study protocol: A randomised clinical trial of fibre-rich legumes targeting the gut microbiome, metabolome and gut transit time of overweight and obese patients with a history of noncancerous adenomatous polyps. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e081379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Irajizad, E.; Hoffman, K.L.; Fahrmann, J.F.; Li, F.; Seo, Y.D.; Browman, G.J.; Dennison, J.B.; Vykoukal, J.; Luna, P.N.; et al. Modulating a prebiotic food source influences inflammation and immune-regulating gut microbes and metabolites: Insights from the BE GONE trial. eBioMedicine 2023, 98, 104873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, T.J.; Albert, P.S.; Zhang, Z.; Bagshaw, D.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Ulbrecht, J.; Miller, C.K.; Bobe, G.; Colburn, N.H.; Lanza, E. Consumption of a legume-enriched, low-glycemic index diet is associated with biomarkers of insulin resistance and inflammation among men at risk for colorectal cancer. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lanza, E.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Colburn, N.H.; Bagshaw, D.; Rovine, M.J.; Ulbrecht, J.S.; Bobe, G.; Chapkin, R.S.; Hartman, T.J. A high legume low glycemic index diet improves serum lipid profiles in men. Lipids 2010, 45, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lanza, E.; Ross, A.C.; Albert, P.S.; Colburn, N.H.; Rovine, M.J.; Bagshaw, D.; Ulbrecht, J.S.; Hartman, T.J. A high-legume low-glycemic index diet reduces fasting plasma leptin in middle-aged insulin-resistant and -sensitive men. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Yu, N.; Hartman, T.J.; Mitchell, D.C.; Lawrence, F.R.; Aukema, H.M. Pulse consumption in Canadian adults influences nutrient intakes. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S27–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, D.C.; Lawrence, F.R.; Hartman, T.J.; Curran, J.M. Consumption of dry beans, peas, and lentils could improve diet quality in the US population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparvoli, F.; Giofré, S.; Cominelli, E.; Avite, E.; Giuberti, G.; Luongo, D.; Gatti, E.; Cianciabella, M.; Daniele, G.M.; Rossi, M.; et al. Sensory Characteristics and Nutritional Quality of Food Products Made with a Biofortified and Lectin Free Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Flour. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparvoli, F.; Laureati, M.; Pilu, R.; Pagliarini, E.; Toschi, I.; Giuberti, G.; Fortunati, P.; Daminati, M.G.; Cominelli, E.; Bollini, R. Exploitation of Common Bean Flours with Low Antinutrient Content for Making Nutritionally Enhanced Biscuits. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method of Homogenization | Mean Protein Conc in Supernatant (mg/mL) 1 | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical vortex, 30 s | 16.5 | 0.8 |

| Multi-tube vortex, 60 min | 16.8 | 0.2 |

| FastPrep-24, 6 m/s, 30 s × 10 cycles, 30 s dwell on ice cold acetone between cycles, 30 stainless steel beads | 20.6 | 0.1 |

| Bead Ruptor Elite, 6 m/s, 1 min × 1 cycle, 10 stainless steel beads | 23.1 | 0.9 |

| Market Class | DRK | WK | BLK | PNT 1 | PNT 2 | PNT Heidi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAU | 8192 | 4096 | 4096 | 2048 | 8 | 1 |

| PHA mg/g dry weight | 223.06 ± 0.07 | 144.0 ± 0.01 | 86.82 ± 0.02 | 93.78 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 3.60 × 10−5 | 0.008 ± 2.76 × 10−6 |

| Market Class | DRK | WK | BLK | PNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAU | 16 | 4 | 64 | 8 |

| PHA mg/g dry weight | 0.0049 ± 1.53 × 10−7 | 0.0047 ± 5.27 × 10−6 | 0.0038 ± 5.59 × 10−7 | 0.0038 ± 1.23 × 10−7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thompson, H.J.; Neil, E.S.; McGinley, J.N.; Lutsiv, T. Toward Standardized Measurement of Active Phytohemagglutinin in Common Bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, L. Foods 2025, 14, 4247. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244247

Thompson HJ, Neil ES, McGinley JN, Lutsiv T. Toward Standardized Measurement of Active Phytohemagglutinin in Common Bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, L. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4247. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244247

Chicago/Turabian StyleThompson, Henry J., Elizabeth S. Neil, John N. McGinley, and Tymofiy Lutsiv. 2025. "Toward Standardized Measurement of Active Phytohemagglutinin in Common Bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, L." Foods 14, no. 24: 4247. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244247

APA StyleThompson, H. J., Neil, E. S., McGinley, J. N., & Lutsiv, T. (2025). Toward Standardized Measurement of Active Phytohemagglutinin in Common Bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, L. Foods, 14(24), 4247. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244247