Exploring Instant Noodle Consumption Patterns and Consumer Awareness in Kosovo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Respondent Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Perceptions of Pre-Packaged Noodles

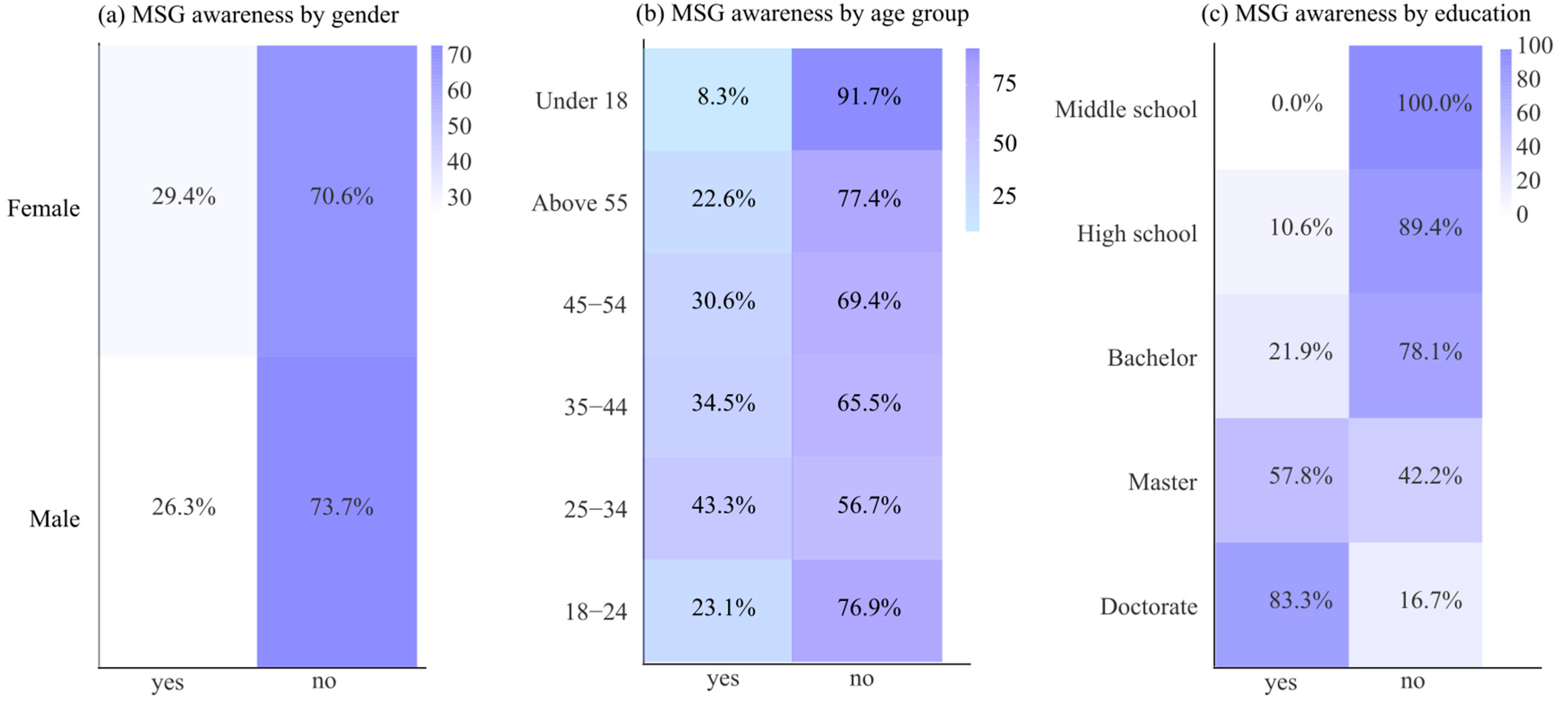

3.2. Knowledge and Health Concerns

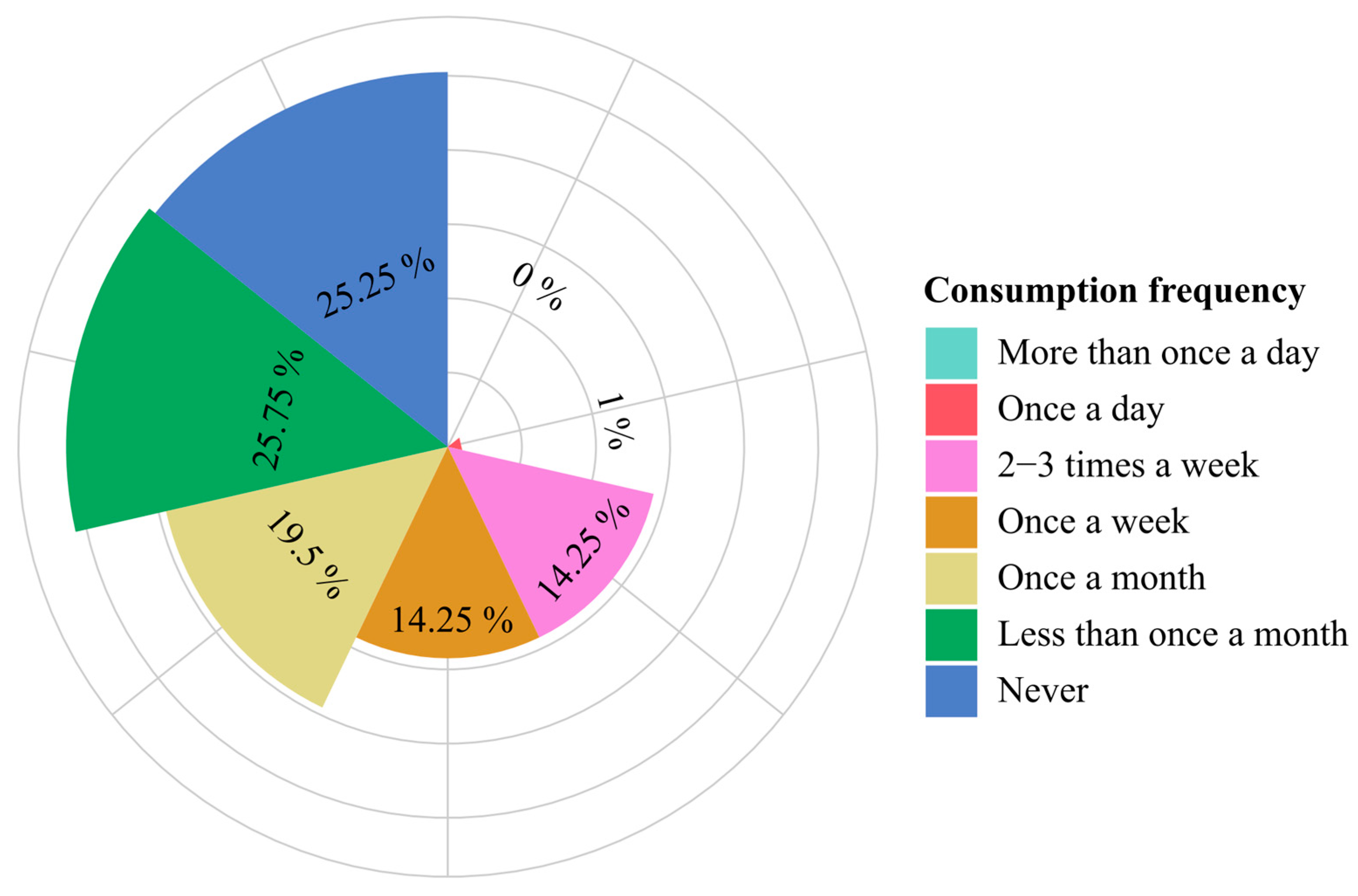

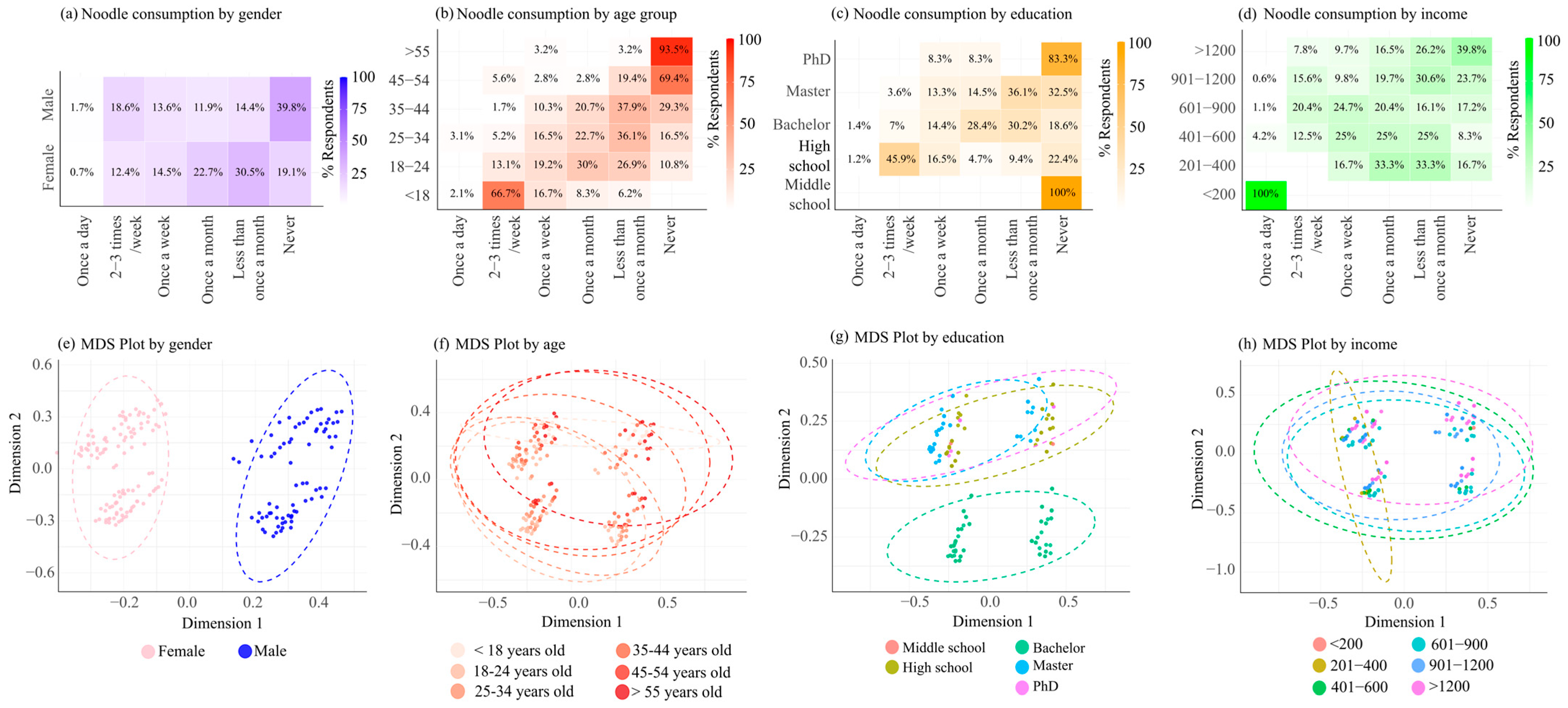

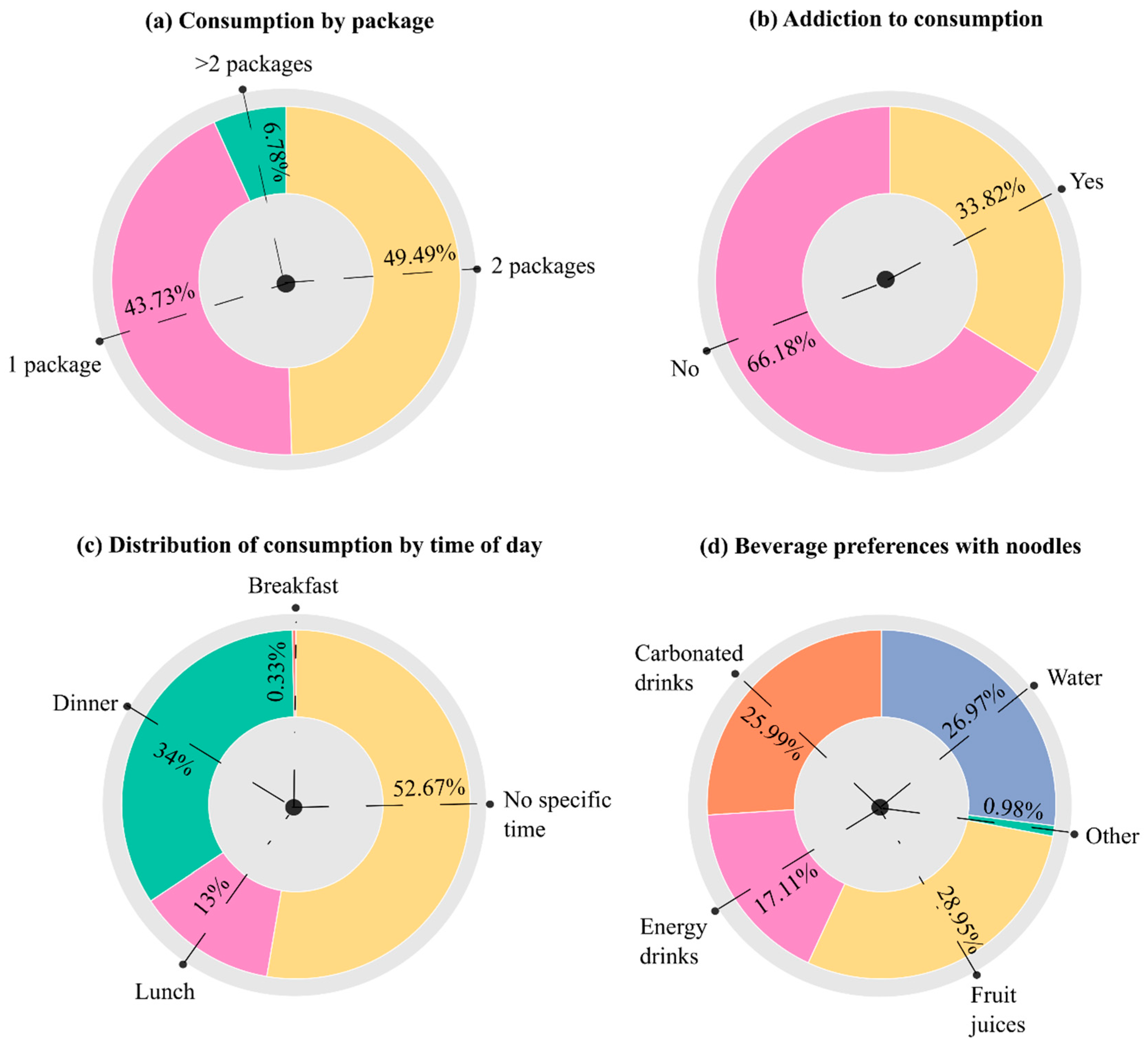

3.3. Consumption Behavior of Pre-Packaged Noodles

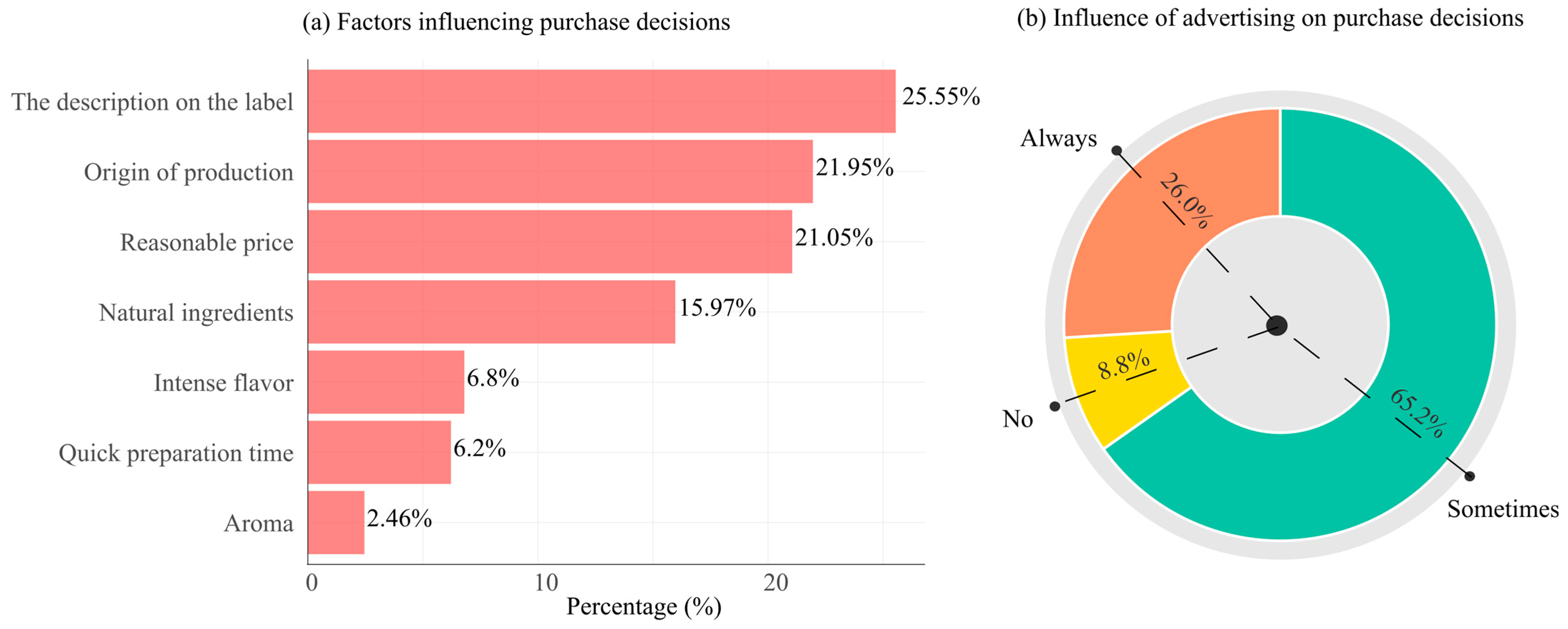

3.4. Factors Influencing Noodle Purchases

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gulia, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Khatkar, B. Instant Noodles: Processing, Quality, and Nutritional Aspects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1386–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Instant Noodles Association. 世界ラーメン協会 2021, Ikeda, Osaka, Japan. Available online: https://instantnoodles.org/en/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Koh, W.Y.; Matanjun, P.; Lim, X.X.; Kobun, R. Sensory, Physicochemical, and Cooking Qualities of Instant Noodles Incorporated with Red Seaweed (Eucheuma denticulatum). Foods 2022, 11, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, S.U. Role of Food Additives on Functional and Nutritional Properties of Noodles: A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2021, 10, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation-231/2012-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2012/231/oj/eng (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Kamal, A.H.; El-Malla, S.F.; Elattar, R.H.; Mansour, F.R. Determination of Monosodium Glutamate in Noodles Using a Simple Spectrofluorometric Method Based on an Emission Turn-on Approach. J. Fluoresc. 2023, 33, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adejuwon, O.H.; Jideani, A.I.O.; Falade, K.O. Quality and Public Health Concerns of Instant Noodles as Influenced by Raw Materials and Processing Technology. Food Rev. Int. 2020, 36, 276–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Park, J.; Jung, H.; Jeong, J.; Lim, K.; Shin, S. Association of Hypertension with Noodle Consumption Among Korean Adults Based on the Health Examinees (HEXA) Study. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2024, 18, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colozza, D. A Qualitative Exploration of Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption and Eating out Behaviours in an Indonesian Urban Food Environment. Nutr. Health 2022, 30, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, A.; Hu, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. Effect of Frying Process on Nutritional Property, Physicochemical Quality, and In Vitro Digestibility of Commercial Instant Noodles. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 823432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.O.; Akinnusi, E.; Ottu, P.O.; Bridget, K.; Oyubu, G.; Ajiboye, S.A.; Waheed, S.A.; Collette, A.C.; Adebimpe, H.O.; Nwokafor, C.V.; et al. The Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Cardiovascular Diseases and Cancer: Epidemiological and Mechanistic Insights. Asp. Mol. Med. 2025, 5, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, V.J.P.D. Food Marketing as a Special Ingredient in Consumer Choices: The Main Insights from Existing Literature. Foods 2020, 9, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guner, C.; Basdogan, H.; Eris, A. Consumption Behaviors and Factors Influencing Preferences for Instant Noodles: The Case of Turkiye. Int. J. Gastron. Res. 2024, 3, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, J.Y.; Loo, B.W.; Boon, J.G.; Ahmad, N.; Abu Bakar, T.H.S.T.; Lum, W.C. Influential Factors on Consumer Intention of Instant Noodle Consumption: Evidence from Kelantan Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1397, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarga, M.F.; Muhandri, T.; Hasanah, U. Effectiveness, Consumer’s Perception, and Behavior Towards Healthier Choice Logo on Indonesian Instant Noodles in Jakarta. J. Gizi Pangan 2024, 19, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, C.J. Influential Factors on Consumer Purchase Intentions: Cases of Instant Noodle Products in the Hungarian Market. J. East. Eur. Cent. Asian Res. (JEECAR) 2018, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. Statistics, an Introductory Analysis; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation-2016/679-EN-Gdpr-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj/eng (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Bolhuis, D.P.; Roodenburg, A.J.C.; Groen, A.P.J.P.; Huybers, S. Dutch Consumers’ Attitude towards Industrial Food Processing. Appetite 2024, 201, 107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, V.; Raghupathi, W. The Influence of Education on Health: An Empirical Assessment of OECD Countries for the Period 1995–2015. Arch. Public Health 2020, 78, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Using the Nutrition Facts Label: For Older Adults|FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-facts-label/using-nutrition-facts-label-older-adults (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Miller, L.M.S.; Applegate, E.; Beckett, L.A.; Wilson, M.D.; Gibson, T.N. Age Differences in the Use of Serving Size Information on Food Labels: Numeracy or Attention? Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Chung, S.-J.; Wong, R.; Lee, B.; Kim, H.; Zhu, B. Effect of Familiarity, Brand Loyalty and Food Neophobicity on Food Acceptance: A Case Study of Instant Noodles with Consumers in Seoul, Beijing, and Shanghai. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 10, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancone, S.; Corrado, S.; Tosti, B.; Spica, G.; Di Siena, F.; Misiti, F.; Diotaiuti, P. Enhancing Nutritional Knowledge and Self-Regulation Among Adolescents: Efficacy of a Multifaceted Food Literacy Intervention. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1405414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiefer, I.; Rathmanner, T.; Kunze, M. Eating and Dieting Differences in Men and Women. J. Men’s Health Gend. 2005, 2, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P. Enhancing Adolescent Food Literacy Through Mediterranean Diet Principles: From Evidence to Practice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, T.E.; Brennan, S.F.; Woodside, J.V.; McKinley, M.C. What Makes Interventions Aimed at Improving Dietary Behaviours Successful in the Secondary School Environment? A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2448–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Peschel, A.O. How Circular Will You Eat? The Sustainability Challenge in Food and Consumer Reaction to Either Waste-to-Value or yet Underused Novel Ingredients in Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreani, G.; Banovic, M.; Dagevos, H.; Sogari, G. Chapter 25—Consumer Perceptions and Market Analysis of Plant-Based Foods: A Global Perspective. In Handbook of Plant-Based Food and Drinks Design; Boukid, F., Rosell, C.M., Gasparre, N., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 393–408. ISBN 978-0-443-16017-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanu, M.-M.; Flocea, E.-I.; Boișteanu, P.-C. The Impact of Artificial and Natural Additives in Meat Products on Neurocognitive Food Perception: A Narrative Review. Foods 2024, 13, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaharini, S.; Ganapathy, D. Knowledge and Awareness of Monosodium Glutamate (Ajinomoto Salt) Among Students. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2020, 32, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.E.; Lee, K.W.; Cho, M.S. Noodle Consumption Patterns of American Consumers: NHANES 2001–2002. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2010, 4, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsubhi, M.; Blake, M.; Nguyen, T.; Majmudar, I.; Moodie, M.; Ananthapavan, J. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Healthier Food Products: A Systematic Review. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Consumer Science in the Balkans: Frameworks, Protocols and Networks for a Better Knowledge of Food Behaviours|FP7|CORDIS|Europäische Kommission. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/212579/reporting/de (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Milošević, J.; Žeželj, I.; Gorton, M.; Barjolle, D. Understanding the Motives for Food Choice in Western Balkan Countries. Appetite 2012, 58, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.J.; Cho, E.; Lee, H.-J.; Fung, T.T.; Rimm, E.; Rosner, B.; Manson, J.E.; Wheelan, K.; Hu, F.B. Instant Noodle Intake and Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Distinct Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Korea. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prameswari, S.A.; Toiba, H.; Andriani, D.R.; Noor, A.Y.M. Millennial Consumer Preferences for Healthy Instant Noodle Products in East Java (Choice Experiment Method). Habitat 2025, 36, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock University Research Portal. Available online: https://researchportal.babcock.edu.ng/publication/view/4664 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Bogard, J.R.; Downs, S.; Casey, E.; Farrell, P.; Gupta, A.; Miachon, L.; Naughton, S.; Staromiejska, W.; Reeve, E. Convenience as a Dimension of Food Environments: A Systematic Scoping Review of Its Definition and Measurement. Appetite 2024, 194, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joya, K.; Orth, U.R. Consumers’ Lay Theories on Food Safety: Insights from a Q-Methodology Study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 133, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, A.O.E.; Shofa, H.M.; Shani, N.N.; Wulandari, W.; Aini, L.N.; Rosyada, T.A.; Ikaningtyas, M. Planning and Development of INROLL Noodle Business as an Innovation of Instant Noodle-Based Snacks among the Younger Generation. J. Pemberdaya. Ekon. Masy. 2025, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjarnahor, S.; Hardini, S.Y.P.K.; Gandhy, A. The Effect of Positioning and Product Differentiation on Consumer Loyalty of Indomie Instant Noodles. Proceeding Int. Semin. Sci. Technol. 2024, 3, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuraini, R.; Sinaga, V.L.; Yusnanto, T.; Kusnadi, I.H.; Hadayanti, D. Analysis of The Influence of Online Selling, Digital Brand Image and Digital Promotion on Purchase Intention of Instant Noodle Products. J. Sistim Inf. Teknol. 2024, 6, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabelessy, W. The Ability of Brand Trust as a Mediator on the Determinants of Customer Loyalty: Study on Mie Sagu Waraka (SAWA) in Ambon, Indonesia. Open Access Indones. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 400) | Percentage 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 282 | 70.5 |

| Male | 118 | 29.5 | |

| Age | Under 18 | 48 | 12.0 |

| 18–24 | 130 | 32.5 | |

| 25–34 | 97 | 24.3 | |

| 35–44 | 58 | 14.5 | |

| 45–54 | 36 | 9.0 | |

| Above 55 | 31 | 7.8 | |

| Education | Middle school | 5 | 1.3 |

| High school | 85 | 21.3 | |

| Bachelor | 215 | 53.8 | |

| Master | 83 | 20.8 | |

| PhD | 12 | 3.0 | |

| Income (euro) | <200 | 1 | 0.3 |

| 201–400 | 6 | 1.5 | |

| 401–600 | 24 | 6.0 | |

| 601–900 | 93 | 23.3 | |

| 901–1200 | 173 | 43.2 | |

| Above 1200 | 103 | 25.7 | |

| Statements | Categories (%) | Correlations 1 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Education | Age | ||||||||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean ± SD | Mann-Whitney U | p-Value | Kruskal-Wallis H | p-Value | Spearman’s Rho | p-Value | |

| They are healthy. | 7.4 | 23.2 | 45.2 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 2.59 ± 0.76 | 16,207.5 | 0.65 | 39.81 | 0.00 | −0.40 | 0.00 |

| Pre-packaged noodles are a less healthy alternative compared to traditional cooking. | 1.8 | 3.2 | 19.8 | 50.0 | 5.2 | 3.67 ± 0.75 | 16,357.0 | 0.76 | 32.17 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| The salt content is low. | 6.4 | 25.4 | 42.8 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 2.61 ± 0.78 | 13,462.0 | 0.001 | 42.52 | 0.00 | −0.44 | 0.00 |

| They contribute to weight gain. | 1.6 | 4.0 | 37.2 | 32.0 | 5.2 | 3.44 ± 0.77 | 16,067.0 | 0.55 | 26.59 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.00 |

| The list of ingredients on the packaging is easy to understand. | 1.8 | 8.4 | 21.8 | 43.8 | 4.2 | 3.50 ± 0.84 | 14,825.5 | 0.06 | 18.378 | 0.001 | −0.16 | 0.001 |

| Frequent consumption of pre-packaged noodles may negatively affect my health. | 1.2 | 1.8 | 14.4 | 47.4 | 15.2 | 3.92 ± 0.77 | 15,060.0 | 0.09 | 51.47 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 |

| Statements | Responses (%) | Correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Education | Age | |||||

| Chi-Square | p-Value | Chi-Square | p-Value | Chi-Square | p-Value | ||

| Salt content | 20.36 | 11.208 | 0.011 | 48.291 | 0.00 | 134.627 | 0.00 |

| Additives and preservatives | 32.05 | ||||||

| Fat and calories | 37.14 | ||||||

| No, I have no concerns | 10.45 | ||||||

| Statements | Responses (%) | Correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Education | Age | |||||

| Chi-Square | p-Value | Chi-Square | p-Value | Chi-Square | p-Value | ||

| Yes | 28.5 | 0.408 | 0.523 | 72.775 | 0.00 | 23.508 | 0.00 |

| No | 71.5 | ||||||

| Statements | Responses (%) | Correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | ||||

| Chi-Square | p-Value | Chi-Square | p-Value | ||

| I don’t have time to prepare meals. | 75.17 | 33.629 | 0.00 | 60.550 | 0.00 |

| I don’t know how to cook so I choose ready-made meals. | 19.54 | ||||

| It’s a convenient choice on breaks. | 5.29 | ||||

| Statements | Responses (%) | Correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption Frequency | Packages Consumed | ||||

| Chi-Square | p-Value | Chi-Square | p-Value | ||

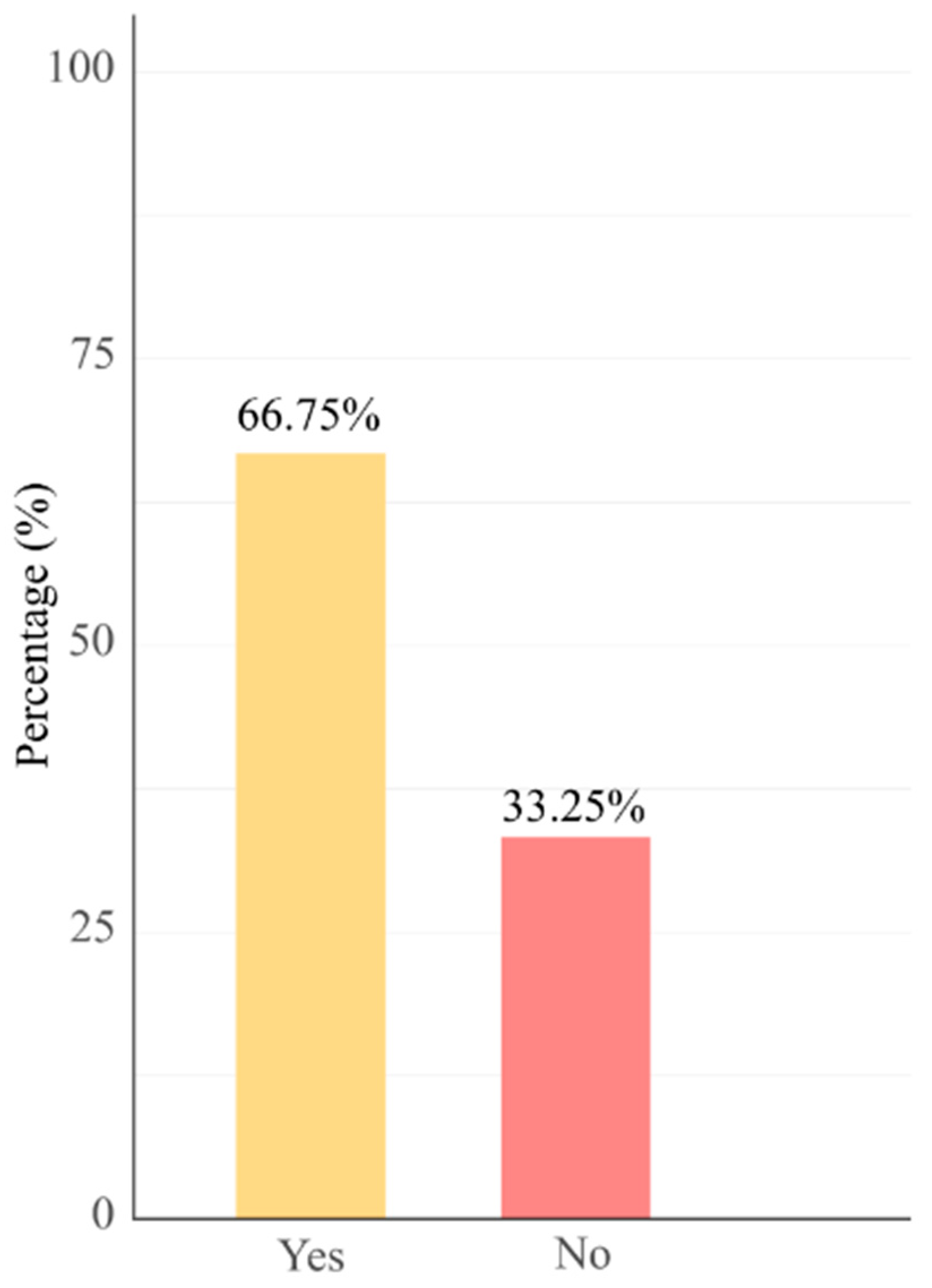

| Yes | 33.82 | 321.773 | 0.00 | 194.557 | 0.00 |

| No | 66.18 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salihu, S.; Elezaj, B.; Qorri, D.; Gashi, N. Exploring Instant Noodle Consumption Patterns and Consumer Awareness in Kosovo. Foods 2025, 14, 4245. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244245

Salihu S, Elezaj B, Qorri D, Gashi N. Exploring Instant Noodle Consumption Patterns and Consumer Awareness in Kosovo. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4245. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244245

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalihu, Salih, Besjana Elezaj, Dejsi Qorri, and Njomza Gashi. 2025. "Exploring Instant Noodle Consumption Patterns and Consumer Awareness in Kosovo" Foods 14, no. 24: 4245. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244245

APA StyleSalihu, S., Elezaj, B., Qorri, D., & Gashi, N. (2025). Exploring Instant Noodle Consumption Patterns and Consumer Awareness in Kosovo. Foods, 14(24), 4245. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244245