Explaining Food Waste Dissimilarities in the European Union: An Analysis of Economic, Demographic, and Educational Dimensions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Food Waste and the Economic, Social and Demographic Factors

2.2. Convergences and Disparities Among EU Member States

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Selected Variables

3.3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Factor Analysis Results and Interpretation

4.2. Testing Hypothesis H1: Nonlinear Relationships Explored Through the MLP Model

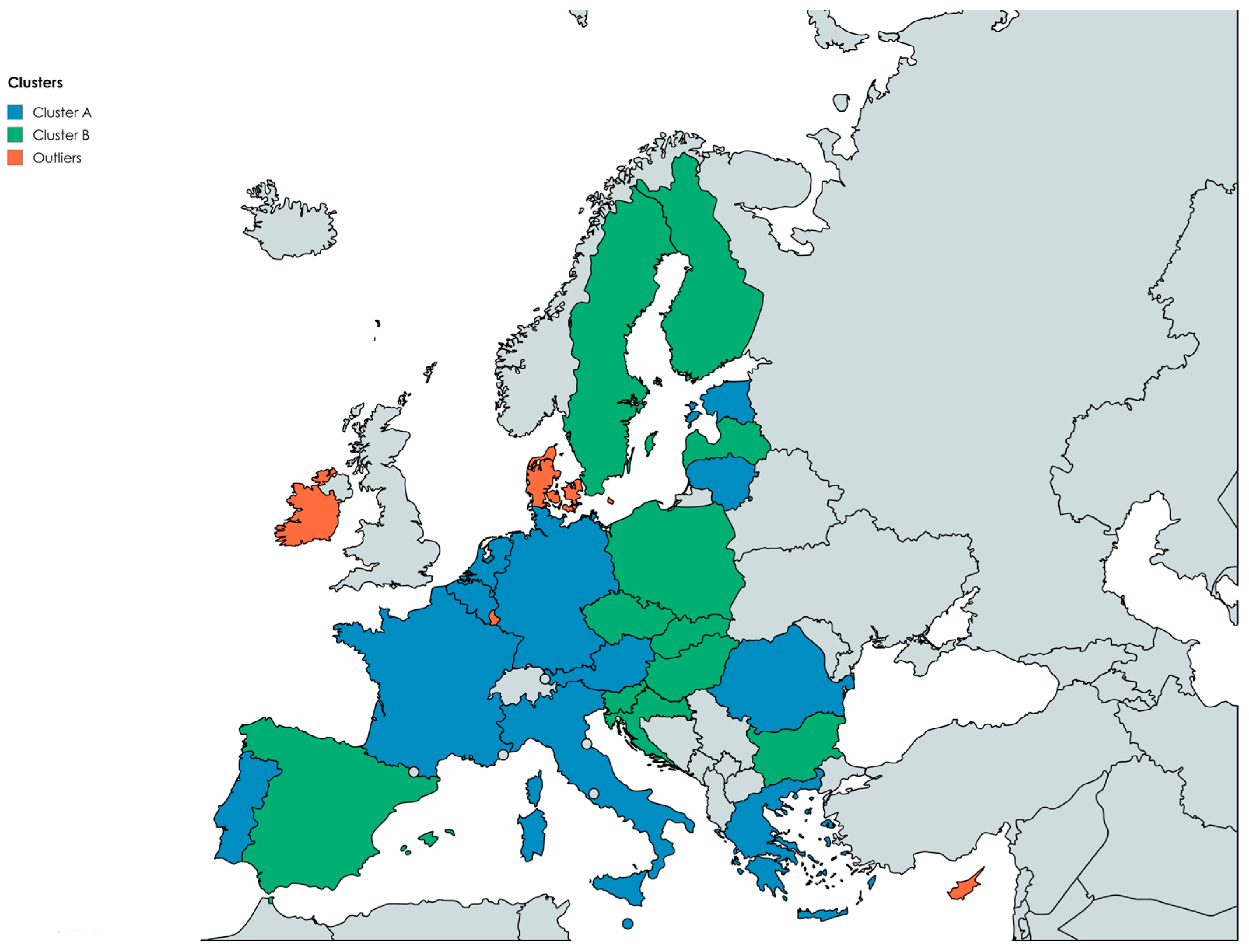

4.3. Testing Hypothesis H2: Cluster-Based Differences in Food Waste Patterns

5. Discussions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| FW | Food waste |

| PD | Population density |

| GDPpc | Gross domestic product per capita |

| PTE | Percentage of tertiary education (levels 5–8) |

| FCEH | Final consumption expenditure of households |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2021; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Tutar, H.; Streimikiene, D.; Mutlu, H.T.; Kloudova, J.; Bilan, Y. Global food waste as an anti-sustainability trend: Analysis of economic and environmental impacts across countries. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 674–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencia, A.D.; Bălan, I.M. Reevaluating Economic Drivers of Household Food Waste: Insights, Tools, and Implications Based on European GDP Correlations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Grebski, W.W. Analysis of Waste Trends in the European Union (2021–2023): Sectorial Contributions, Regional Differences, and Socioeconomic Factors. Foods 2025, 14, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, C.; De Laurentiis, V.; Corrado, S.; van Holsteijn, F.; Sala, S. Quantification of Food Waste per Product Group along the Food Supply Chain in the European Union. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, S.; Sala, S. Food waste accounting along global and European food supply chains: State of the art and outlook. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, L.; Williams, H. Avoidance of Supermarket Food Waste—Employees’ Perspective on Causes and Measures to Reduce Fruit and Vegetables Waste. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunditsakulchai, P.; Liu, C. Integrated Strategies for Household Food Waste Reduction in Bangkok. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanussen, H.; Loy, J.-P.; Egamberdiev, B. Determinants of Food Waste from Household Food Consumption: A Case Study from Field Survey in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittuari, M.; Garcia Herrero, L.; Masotti, M.; Iori, E.; Caldeira, C.; Qian, Z.; Bruns, H.; van Herpen, E.; Obersteiner, G.; Kaptan, G.; et al. How to reduce consumer food waste at household level: A literature review on drivers and levers for behavioural change. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E.; Choedron, K.T.; Ajai, O.; Duke, O.; Jijingi, H.E. Systematic review of factors influencing household food waste behaviour: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Manage. Res. 2024, 43, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloha, R.; Dace, E. Research on quantification of food loss and waste in Europe: A systematic literature review and synthesis of methodological limitations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2025, 28, 200287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekavičius, V.; Bobinaitė, V.; Kliaugaitė, D.; Rimkūnaitė, K. Socioeconomic Impacts of Food Waste Reduction in the European Union. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canali, M.; Amani, P.; Aramyan, L.; Gheoldus, M.; Moates, G.; Östergren, K.; Silvennoinen, K.; Waldron, K.; Vittuari, M. Food Waste Drivers in Europe, from Identification to Possible Interventions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.; Lucas, M.R.; Marta-Costa, A. Food Waste Reduction: A Systematic Literature Review on Integrating Policies, Consumer Behavior, and Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.; Brown, C.; Arneth, A.; Finnigan, J.; Rounsevell, M.D. Losses, inefficiencies, and waste in the global food system. Agric. Syst. 2017, 153, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vărzaru, A.A. Digital Revolution in Agriculture: Using Predictive Models to Enhance Agricultural Performance Through Digital Technology. Agriculture 2025, 15, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hebrok, M.; Boks, C. Household food waste: Drivers and potential intervention points for design—An extensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Secondi, L.; Pratesi, C.A. Reducing food waste: An investigation on the behavior of Italian youths. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, E.; Sahin, H.; Topaloglu, Z.; Oledinma, A.; Huda, A.K.S.; Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M.; van’t Wout, T.; Kamrava, M. A Consumer Behavioural Approach to Food Waste. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesiranta, N.; Närvänen, E.; Mattila, M. Framings of Food Waste: How Food System Stakeholders Are Responsibilized in Public Policy Debate. J. Public Policy Mark. 2021, 41, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaziani, S.; Ghodsi, D.; Schweikert, K.; Dehbozorgi, G.; Rasekhi, H.; Faghih, S.; Doluschitz, R. The Need for Consumer-Focused Household Food Waste Reduction Policies Using Dietary Patterns and Socioeconomic Status as Predictors: A Study on Wheat Bread Waste in Shiraz, Iran. Foods 2022, 11, 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpino, G. Household food waste behavior: Avenues for future research. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Matthies, E. Where to start fighting the food waste problem? Identifying most promising entry points for intervention programs to reduce household food waste and overconsumption of food. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laurentiis, V.; Corrado, S.; Sala, S. Quantifying household waste of fresh fruit and vegetables in the EU. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, S.; Rather, M.I.; Zargar, U.R. Understanding the Food Waste Behaviour in University Students: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaryani, R.L.; Palouj, M.; Gholami, H.; Baghestany, A.A.; Damirchi, M.J.; Dadar, M.; Seifollahi, N. Predicting Household Food Waste Behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vărzaru, A.A.; Simion, D. Exploring the Drivers of Food Waste in the EU: A Multidimensional Analysis Using Cluster and Neural Network Models. Foods 2025, 14, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slorach, P.C.; Jeswani, H.K.; Cuellar-Franca, R.; Azapagic, A. Environmental and economic implications of recovering resources from food waste in a circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazli, N.A.A.; Hapiz, H.Y.; Ghazali, M.S. Determinants of Consumer Food Waste Behaviour in Malaysia Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 131, 05020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.-X.; Wu, X.-Q.; Cui, T.; Yang, Z.-N.; Chen, Y.-H. New Insights into the Link between Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Household Food Waste Behaviours in China. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 42, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Identifying Motivations and Barriers to Minimizing Household Food Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; Ujang, Z.B. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtokunnas, T.; Mattila, M.; Närvänen, E.; Mesiranta, N. Towards a Circular Economy in Food Consumption: Food Waste Reduction Practices as Ethical Work. J. Consum. Cult. 2020, 22, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Fuchs, D. Strong sustainable consumption governance—Precondition for a degrowth path? J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 38, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrello, M.; Caracciolo, F.; Lombardi, A.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. Consumers’ Perspective on Circular Economy Strategy for Reducing Food Waste. Sustainability 2017, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M.; Lee, H.; Aktas, E.; Topaloglu, Z.; van’t Wout, T.; Huda, S. Managing Food Security through Food Waste and Loss: Small Data to Big Data. Comput. Oper. Res. 2018, 98, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhong, D.; Zhou, W.; Alami, M.J.; Huang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, B.; Cui, S. Environmental-Economic Effects on Agricultural Applications of Food Waste Disposal Products. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 209, 107797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H.G.; Kan, M. For Sustainability Environment: Some Determinants of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Agricultural Sector in EU-27 Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 32441–32448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamasiga, P.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H.; Hart, A. Food Waste and Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimnadis, K.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Arabatzis, G.; Leontopoulos, S.; Zervas, E. An Innovative and Alternative Waste Collection Recycling Program Based on Source Separation of Municipal Solid Wastes (MSW) and Operating with Mobile Green Points (MGPs). Sustainability 2023, 15, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimnadis, K.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L. Investigating the Role of Municipal Waste Treatment within the European Union through a Novel Created Common Sustainability Point System. Recycling 2024, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimnadis, K.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Leontopoulos, S. Practical Improvement Scenarios for an Innovative Waste-Collection Recycling Program Operating with Mobile Green Points (MGPs). Inventions 2023, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimnadis, K.; Katsenios, G.; Fanourakis, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Kyriakakis, A.; Kyriakakis, D.; Tsagkaropoulos, D. Evaluating the Effects of Irrigation with Reused Water and Compost from a Pilot Wastewater Treatment Unit on the Experimental Growth of Two Common Ornamental Plant Species in the City of Athens. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Strid, I.; Hansson, P.A. Carbon footprint of food waste management options in the waste hierarchy—A Swedish case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 93, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoy-Muñoz, P.; Cardenete, M.A.; Delgado, M.C. Economic impact assessment of food waste reduction on European countries through social accounting matrices. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2019/1597 Supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC on Waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, 248, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Handbook on Supply and Use Tables and Input-Output Tables with Extensions and Applications; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/SUT_IOT_HB_Final_Cover.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources—Summary Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i3347e/i3347e.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Pelau, C.; Sarbu, R.; Serban, D. Cultural Influences on Fruit and Vegetable Food-Wasting Behavior in the European Union. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macková, M.; Hazuchová, N.; Stávková, J. Czech Consumers’ Attitudes to Food Waste. Agric. Econ. 2019, 65, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vărzaru, A.A. Unveiling Digital Transformation: A Catalyst for Enhancing Food Security and Achieving Sustainable Development Goals at the European Union Level. Foods 2024, 13, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaqué, L.G. French and Italian Food Waste Legislation: An Example for Other EU Member States to Follow? Eur. Food Feed Law Rev. 2017, 12, 224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Black, D.; Wei, T.; Eaton, E.; Hunt, A.; Carey, J.; Schmutz, U.; He, B.; Roderick, I. Testing Food Waste Reduction Targets: Integrating Transition Scenarios with Macro-Valuation in an Urban Living Lab. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggi, G.; Principato, L.; Castellacci, F. Food Waste Reduction, Corporate Responsibility and National Policies: Evidence from Europe. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 470–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippidis, G.; Sartori, M.; Ferrari, E.; M’Barek, R. Waste not, want not: A bio-economic impact assessment of household food waste reductions in the EU. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campoy-Muñoz, P.; Cardenete, M.A.; Delgado, M.D.C.; Sancho, F. Food Losses and Waste: A Needed Assessment for Future Policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. From Farm to Fork: Our Food, Our Health, Our Planet, Our Future; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Food Donation Guidelines; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste/food-donation_en (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Friman, A.; Hyytiä, N. The Economic and Welfare Effects of Food Waste Reduction on a Food-Production-Driven Rural Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boni, A.; Ottomano Palmisano, G.; De Angelis, M.; Minervini, F. Challenges for a Sustainable Food Supply Chain: A Review on Food Losses and Waste. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albizzati, P.F.; Rocchi, P.; Cai, M.; Tonini, D.; Astrup, T.F. Rebound effects of food waste prevention: Environmental impacts. Waste Manag. 2022, 153, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Tian, Y. A Comprehensive Survey of Clustering Algorithms. Ann. Data Sci. 2015, 2, 165–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, E.L.; Hertel, T. Global Food Waste across the Income Spectrum: Implications for Food Prices, Production and Resource Use. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabró, G.; Vieri, S. Food waste and the EU target: Effects on the agrifood systems’ sustainability. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2025, 28, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, C.; Langen, N.; Blumenthal, A.; Teitscheid, P.; Ritter, G. Cutting Food Waste through Cooperation along the Food Supply Chain. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1429–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, Z.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Lyu, L.; An, C.; Peng, H. An Integrated Environmental and Economic Assessment for the Disposal of Food Waste from Grocery Retail Stores towards Resource Recovery. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 63325–63342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usubiaga, A.; Butnar, I.; Schepelmann, P. Wasting Food, Wasting Resources: Potential Environmental Savings through Food Waste Reductions. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 22, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, D.; Laso, J.; Margallo, M.; Ruiz-Salmón, I.; Amo-Setién, F.J.; Abajas-Bustillo, R.; Sarabia, C.; Quiñones, A.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Bala, A.; et al. Introducing a Degrowth Approach to the Circular Economy Policies of Food Production, and Food Loss and Waste Management: Towards a Circular Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helander, H.; Bruckner, M.; Leipold, S.; Petit-Boix, A.; Bringezu, S. Eating Healthy or Wasting Less? Reducing Resource Footprints of Food Consumption. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 054033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santeramo, F.G.; Lamonaca, E. Food Loss–Food Waste–Food Security: A New Research Agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenegger, L.; Hübner, A. Reducing Food Waste at Retail Stores—An Explorative Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Food Waste and Food Waste Prevention by NACE Rev. 2 Activity. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_wasfw__custom_18351658/default/table?page=time:2022 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Population Density. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00003/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Main Components per Capita. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nama_10_pc/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Population in Private Households by Educational Attainment Level—Main Indicators. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/edat_lfse_03__custom_18351776/default/table (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Household Final Consumption Expenditure by Durability. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nama_10_fcs__custom_18351808/default/table (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, J.O. Using IBM SPSS Statistics: An Interactive Hands-On Approach, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Penn State, Eberly College of Science. Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering. Available online: https://online.stat.psu.edu/stat505/lesson/14/14.4 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 3rd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Data | Measures | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| FW | Food waste | Kilograms per capita | [77] |

| PD | Population density | Persons per square kilometer | [78] |

| GDPpc | Gross domestic product per capita | Percentage of EU27 (from 2020) total per capita (based on million purchasing power standards, EU27 from 2020), current prices | [79] |

| PTE | Percentage of tertiary education (levels 5–8) | Percentage | [80] |

| FCEH | Final consumption expenditure of households | Percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) | [81] |

| FW | GDPpc | PTE | FCEH | PD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | Food Waste (FW), kg/capita | 1.000 | 0.111 | 0.205 | 0.043 | 0.119 |

| GDP per capita (GDPpc), % of EU average | 0.111 | 1.000 | 0.582 | −0.823 | 0.126 | |

| Tertiary Education (PTE), % of population | 0.205 | 0.582 | 1.000 | −0.527 | −0.039 | |

| Final Consumption Expenditure of Households (FCEH), % of GDP | 0.043 | −0.823 | −0.527 | 1.000 | −0.226 | |

| Population Density (PD), persons/km2 | 0.119 | 0.126 | −0.039 | −0.226 | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (1-tailed) | Food Waste (FW), kg/capita | 0.163 | 0.033 | 0.353 | 0.144 | |

| GDP per capita (GDPpc), % of EU average | 0.163 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.131 | ||

| Tertiary Education (PTE), % of population | 0.033 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.366 | ||

| Final Consumption Expenditure of Households (FCEH), % of GDP | 0.353 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.021 | ||

| Population Density (PD), persons/km2 | 0.144 | 0.131 | 0.366 | 0.021 | ||

| Initial | Extraction | Factor 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Waste (FW), kg/capita | 1.000 | 0.068 | 0.261 |

| GDP per capita (GDPpc), % of EU average | 0.674 | 0.821 | |

| Tertiary Education (PTE), % of population | 1.000 | 0.259 | 0.509 |

| Final Consumption Expenditure of Households (FCEH), % of GDP | 1.000 | 0.539 | −0.734 |

| Population Density (PD), persons/km2 | 1.000 | 0.045 | 0.211 |

| Parameter Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hidden Layer 1 | Output Layer | Importance | Normalized Importance | ||

| H(1:1) | Food Waste (FW), kg/Capita | ||||

| Input Layer | (Bias) | 0.008 | |||

| Population Density (PD), persons/km2 | 0.233 | 0.157 | 41.4% | ||

| GDP per capita (GDPpc), % of EU average | 0.422 | 0.218 | 57.4% | ||

| Tertiary Education (PTE), % of population | 0.533 | 0.245 | 64.5% | ||

| Final Consumption Expenditure of Households (FCEH), % of GDP | 0.868 | 0.380 | 100.0% | ||

| Hidden Layer 1 | (Bias) | −2.057 | |||

| H(1:1) | 2.597 | ||||

| Clusters | Countries | Food Waste (FW), kg/Capita | Population Density (PD), Persons/km2 | GDP Per Capita (GDPpc), % of EU Average | Tertiary Education (PTE), % of Population | Final Consumption Expenditure of Households (FCEH), % of GDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A | Austria | 131 | 109.6 | 122.9 | 32.5 | 50.4 |

| Germany | 129 | 235.4 | 120.1 | 28.0 | 50.0 | |

| Netherlands | 129 | 517.8 | 133.8 | 38.8 | 43.0 | |

| Belgium | 151 | 383.6 | 118.2 | 40.2 | 48.3 | |

| Estonia | 134 | 31.3 | 83.7 | 36.7 | 51.5 | |

| Lithuania | 140 | 45.2 | 87.1 | 41.3 | 57.0 | |

| France | 139 | 107.6 | 97.2 | 36.9 | 52.2 | |

| Italy | 139 | 198.1 | 97.6 | 18.1 | 59.1 | |

| Malta | 162 | 1696.8 | 103.1 | 29.4 | 49.0 | |

| Portugal | 184 | 115.0 | 77.0 | 26.8 | 68.6 | |

| Romania | 181 | 81.3 | 73.2 | 17.1 | 61.5 | |

| Greece | 196 | 80.3 | 66.7 | 30.5 | 76.1 | |

| Cluster A mean | 151.25 | 300.17 | 98.38 | 31.36 | 55.56 | |

| Cluster B | Slovenia | 71 | 104.8 | 88.7 | 35.1 | 55.4 |

| Spain | 65 | 95.1 | 87.7 | 36.5 | 58.2 | |

| Hungary | 84 | 105.3 | 76.1 | 25.6 | 50.2 | |

| Croatia | 72 | 69.0 | 71.6 | 22.8 | 75.0 | |

| Latvia | 124 | 29.7 | 69.0 | 34.5 | 58.6 | |

| Poland | 123 | 119.8 | 77.9 | 30.0 | 57.3 | |

| Bulgaria | 95 | 58.8 | 62.1 | 26.3 | 59.5 | |

| Slovakia | 106 | 111.5 | 71.0 | 26.0 | 58.3 | |

| Finland | 109 | 18.3 | 106.4 | 35.9 | 48.6 | |

| Sweden | 117 | 25.7 | 113.7 | 41.1 | 44.5 | |

| Czechia | 101 | 138.2 | 89.0 | 23.5 | 48.2 | |

| Cluster B men | 97.00 | 79.65 | 83.02 | 30.66 | 55.80 | |

| Outliers | Cyprus | 294 | 100.6 | 94.3 | 44.0 | 62.0 |

| Denmark | 254 | 140.6 | 133.6 | 35.0 | 43.0 | |

| Ireland | 144 | 75.9 | 236.6 | 46.1 | 23.7 | |

| Luxembourg | 122 | 252.6 | 247.9 | 46.0 | 33.0 | |

| Eu mean | 136.89 | 186.96 | 103.93 | 32.77 | 53.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bocean, C.G. Explaining Food Waste Dissimilarities in the European Union: An Analysis of Economic, Demographic, and Educational Dimensions. Foods 2025, 14, 4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244244

Bocean CG. Explaining Food Waste Dissimilarities in the European Union: An Analysis of Economic, Demographic, and Educational Dimensions. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244244

Chicago/Turabian StyleBocean, Claudiu George. 2025. "Explaining Food Waste Dissimilarities in the European Union: An Analysis of Economic, Demographic, and Educational Dimensions" Foods 14, no. 24: 4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244244

APA StyleBocean, C. G. (2025). Explaining Food Waste Dissimilarities in the European Union: An Analysis of Economic, Demographic, and Educational Dimensions. Foods, 14(24), 4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244244