A Cross-Cultural Study of Health Interests and Pleasure by Consumers in 10 Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Reliability and Correlation of the GHI and Pleasure Subscales

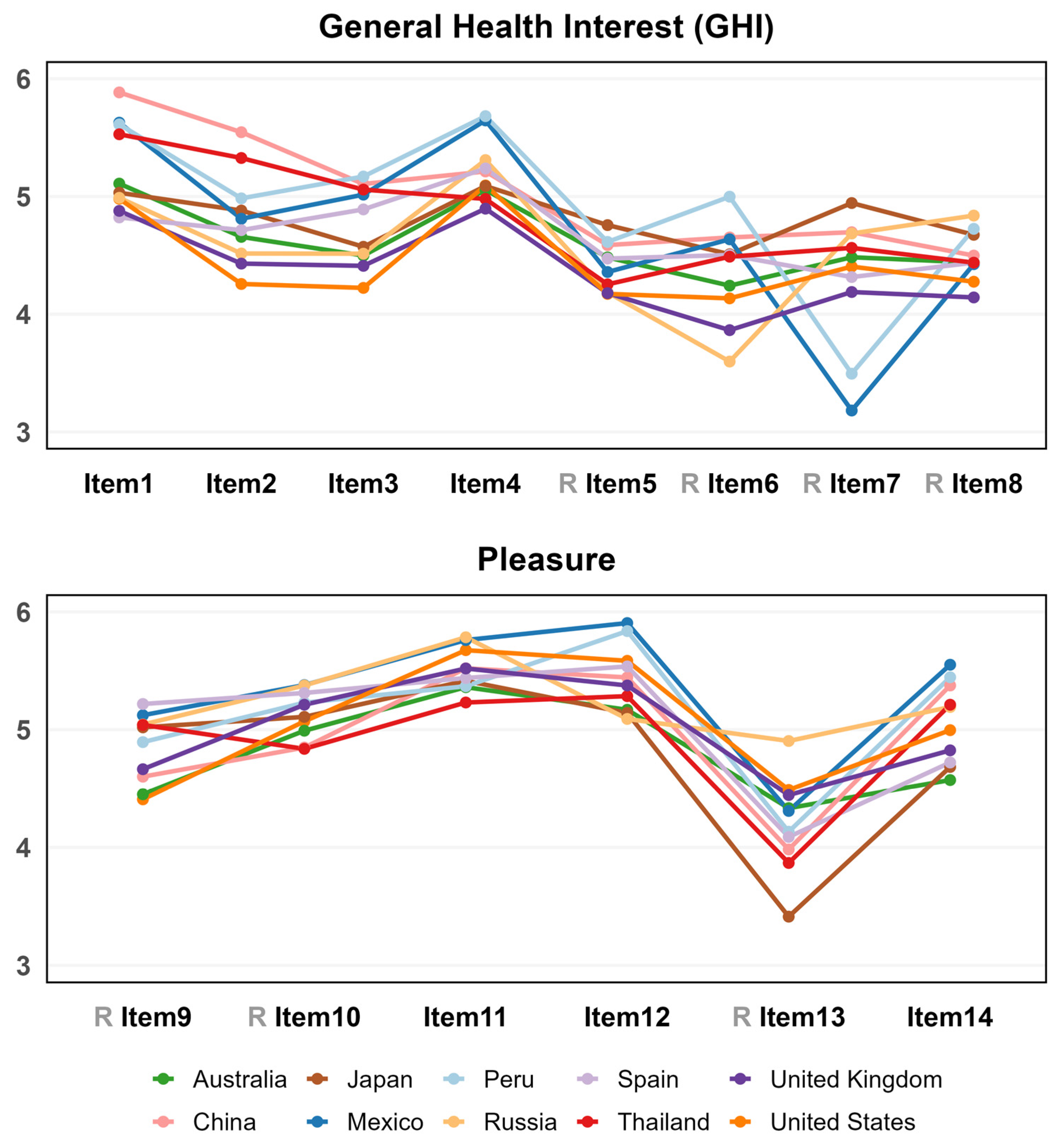

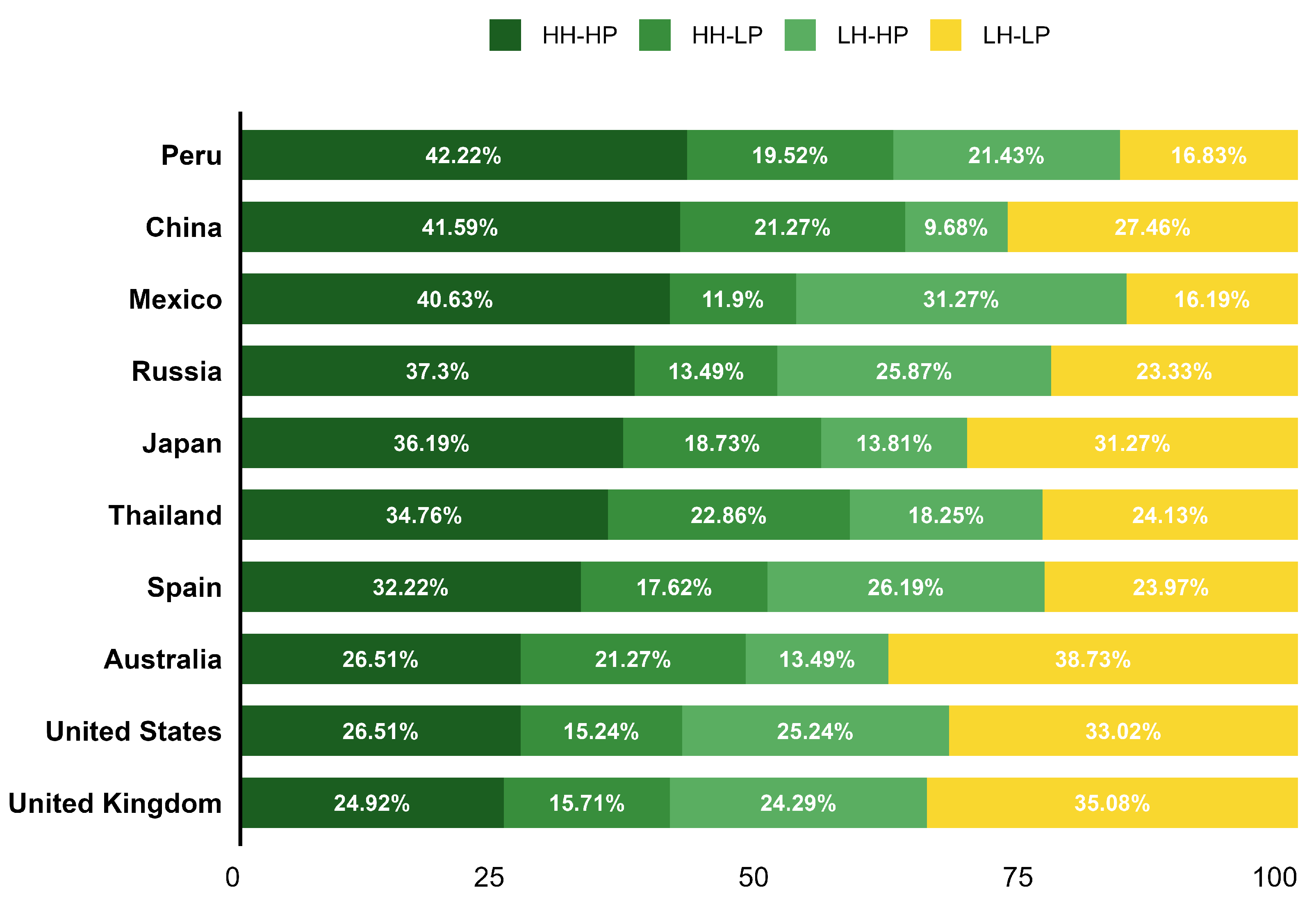

3.2. Cross-Cultural Differences in Health and Pleasure Attitudes

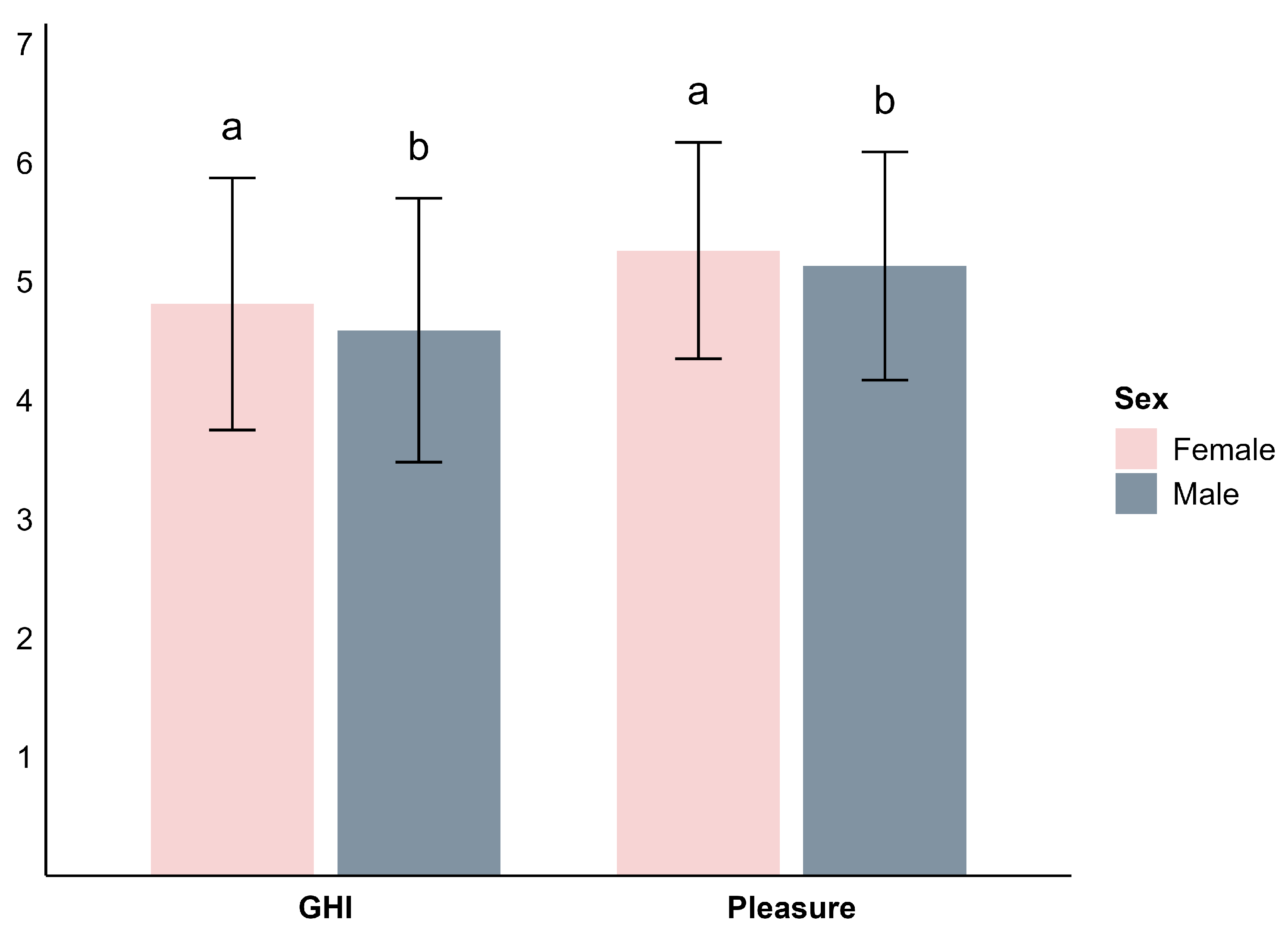

3.3. Demographic Differences in Health and Pleasure Attitudes

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Cross-Cultural Differences in Health and Pleasure Attitudes

4.2. Influence of Demographic Factors on GHI and Pleasure

4.3. Applicability and Limitations of the Health and Taste Attitude Subscales

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fanzo, J.; Davis, C. Can diets be healthy, sustainable, and equitable? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2019, 8, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebylski, M.L.; Redburn, K.A.; Duhaney, T.; Campbell, N.R. Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition 2015, 31, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, S.; Madureira, L. Can healthier food demand be linked to farming systems’ sustainability? The case of the Mediterranean diet. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2019, 10, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumanyika, S.; Afshin, A.; Arimond, M.; Lawrence, M.; McNaughton, S.A.; Nishida, C. Approaches to defining healthy diets: A background paper for the international expert consultation on sustainable healthy diets. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 7S–30S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajetunmobi, O.A.; Laobangdisa, S. The effect of cultural and socio-economic factors on consumer perception. In Consumer Perceptions and Food; Bogueva, D., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, C.; Byrne, D.V.; Andersen, B.V. Sensing the snacking experience: Bodily sensations linked to the consumption of healthy and unhealthy snack foods—A comparison between body mass index levels. Foods 2024, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, L.; Fatemi, H.; Lu, J.; Hertzer, C. The healthier the tastier? USA–India comparison studies on consumer perception of a nutritious agricultural product at different food processing levels. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, M.; Lemieux, S.; Lapointe, A.; Bédard, A.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Bégin, C.; Provencher, V.; Desroches, S. Is eating pleasure compatible with healthy eating? A qualitative study on Quebecers’ perceptions. Appetite 2018, 125, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.; Sinesio, F.; Moneta, E.; Dinnella, C.; Laureati, M.; Torri, L.; Peparaio, M.; Saggia Civitelli, E.; Endrizzi, I.; Gasperi, F.; et al. Measuring consumers attitudes towards health and taste and their association with food-related life-styles and preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorinczi, K. The effect of health conscious trends on food consumption. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Congress, Ghent, Belgium, 26–29 August 2008; European Association of Agricultural Economists: Leuven, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourouniotis, S.; Keast, R.S.J.; Riddell, L.J.; Lacy, K.; Thorpe, M.G.; Cicerale, S. The importance of taste on dietary choice, behaviour and intake in a group of young adults. Appetite 2016, 103, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luomala, H.T.; Paasovaara, R.; Lehtola, K. Exploring consumers’ health meaning categories: Towards a health consumption meaning model. J. Consum. Behav. 2006, 5, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.; Bell, G. Cross-cultural determinants of food acceptability: Recent research on sensory perceptions and preferences. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 6, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. The socio-cultural context of eating and food choice. In Food Choice, Acceptance and Consumption; Meiselman, H.L., MacFie, H.J.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunathan, R.; Naylor, R.W.; Hoyer, W.D. The unhealthy = tasty intuition and its effects on taste inferences, enjoyment, and choice of food products. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werle, C.O.C.; Trendel, O.; Ardito, G. Unhealthy food is not tastier for everybody: The “healthy = tasty” French intuition. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, P.; Frewer, L. Russian consumers’ motives for food choice. Appetite 2009, 52, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervellon, M.-C.; Dubé, L. Cultural Influences in the Origins of Food Likings and Dislikes. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Yang, E.C.L.; Lai, M.Y. Comparing the meanings of food in different Chinese societies: The cases of Taiwan and Malaysia. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 954–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Lai, M.Y. Eat to live or live to eat? Mapping food and eating perception of Malaysian Chinese. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roininen, K.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Tuorila, H. Quantification of consumer attitudes to health and hedonic characteristics of foods. Appetite 1999, 33, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roininen, K.; Tuorila, H.; Zandstra, E.H.; de Graaf, C.; Vehkalahti, K.; Stubenitsky, K.; Mela, D.J. Differences in health and taste attitudes and reported behaviour among Finnish, Dutch and British consumers: A cross-national validation of the health and taste attitude scales (HTAS). Appetite 2001, 37, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M. Consumers’ health and taste attitude in Taiwan: The impacts of modern tainted food worries and gender difference. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubor, A.; Djokic, N.; Djokic, I.; Kovac-Znidersic, R. Application of health and taste attitude scales in Serbia. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 840–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, N.; du Rand, G.; de Kock, H. Perception of gluten-free bread as influenced by information and health and taste attitudes of Millennials. Foods 2022, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G. Methodological issues in cross-cultural sensory and consumer research. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerlund, M.; Andersen, B.V.; Wang, K.; Chan, R.C.K.; Byrne, D.V. Post-ingestive sensations driving post-ingestive food pleasure: A cross-cultural consumer study comparing Denmark and China. Foods 2020, 9, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiselman, H.L. The future in sensory/consumer research: Evolving to a better science. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Chambers, E., IV. Willingness to eat an insect based product and impact on brand equity: A global perspective. J. Sens. Stud. 2019, 34, e12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seninde, D.R.; Chambers, E. Comparing four question formats in five languages for on-line consumer surveys. Methods Protoc. 2020, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtarelli, M.; van Houten, G. Questionnaire translation in the European Company Survey: Conditions conducive to the effective implementation of a TRAPD-based approach. Int. J. Transl. Interpret. Res. 2018, 10, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, J.A. Questionnaire translation. In Cross-Cultural Survey Methods; Harkness, J.A., Van de Vijver, F.J.R., Mohler, P.P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Koppel, K.; Higa, F.; Godwin, S.; Gutierrez, N.; Shalimov, R.; Cardinal, P.; Di Donfrancesco, B.; Sosa, M.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A.; Timberg, L.; et al. Food leftover practices among consumers in selected countries in Europe, South and North America. Foods 2016, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, K.; Suwonsichon, S.; Chambers, D.; Chambers, E., IV. Determination of intrinsic appearance properties that drive dry dog food acceptance by pet owners in Thailand. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 830–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J. Pers. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G.E.; Szodorai, E.T. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luomala, H.; Jokitalo, M.; Karhu, H.; Hietaranta-Luoma, H.-L.; Hopia, A.; Hietamäki, S. Perceived health and taste ambivalence in food consumption. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearty, Á.P.; McCarthy, S.N.; Kearney, J.M.; Gibney, M.J. Relationship between attitudes towards healthy eating and dietary behaviour, lifestyle and demographic factors in a representative sample of Irish adults. Appetite 2007, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiza, H.A.B.; Casavale, K.O.; Guenther, P.M.; Davis, C.A. Diet quality of Americans differs by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education level. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Country Comparison Tool. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool?countries=australia%2Cthailand%2Cunited+kingdom%2Cunited+states (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Shi, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ye, X.; Xue, S.J.; Kakuda, Y. Traditional Chinese medicated diets. In Functional Foods of the East; Shi, J., Ho, C.T., Shahidi, F., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Hernandez, A.; Galagarza, O.A.; Álvarez Rodriguez, M.V.; Pachari Vera, E.; Valdez Ortiz, M.D.C.; Deering, A.J.; Oliver, H.F. Food safety in Peru: A review of fresh produce production and challenges in the public health system. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3323–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayora-Diaz, S.I. Taste, Politics, and Identities in Mexican Food; Bloomsbury Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Honkanen, P. Food preference based segments in Russia. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehaus, A.; Walravens, T. (Eds.) Feeding Japan: The Cultural and Political Issues of Dependency and Risk; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulkerd, S.; Thapsuwan, S.; Thongcharoenchupong, N.; Chamratrithirong, A.; Gray, R.S. Linking fruit and vegetable consumption, food safety and health risk attitudes and happiness in Thailand: Evidence from a population-based survey. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2021, 60, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küster-Boluda, I.; Vidal-Capilla, I. Consumer attitudes in the election of functional foods. Span. J. Mark.—ESIC 2017, 21, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, E.; Pontecorvo, C.; Fasulo, A. Socializing taste. Ethnos 1996, 61, 7–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, P.N. Fat History: Bodies and Beauty in the Modern West; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-8147-9824-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin, P.; Fischler, C.; Imada, S.; Sarubin, A.; Wrzesniewski, A. Attitudes to food and the role of food in life in the U.S.A., Japan, Flemish Belgium and France: Possible implications for the diet-health debate. Appetite 1999, 33, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Haase, A.M.; Steptoe, A.; Nillapun, M.; Jonwutiwes, K.; Bellisle, F. Gender differences in food choice: The contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2004, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, I.; Rathmanner, T.; Kunze, M. Eating and dieting differences in men and women. J. Mens Health Gend. 2005, 2, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-S.; Seo, H.-S. Effects of age group, gender, and consumption frequency on texture perception and liking of cooked rice or bread. Foods 2023, 12, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckett, C.R.; Seo, H.-S. Consumer attitudes toward texture and other food attributes. J. Texture Stud. 2015, 46, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, J.D.; Tylleskär, T.; Lampert, T.; Mensink, G.B.M. Dietary behaviour and socioeconomic position: The role of physical activity patterns. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallinoja, P.; Pajari, P.; Absetz, P. Negotiated pleasures in health-seeking lifestyles of participants of a health promoting intervention. Health 2010, 14, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvy, S.-J.; Pliner, P.P. Social influences on eating in children and adults. In Obesity Prevention; Dubé, L., Bechara, A., Dagher, A., Drewnowski, A., Lebel, J., James, P., Yada, R.Y., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapin, T.; Moreira, C.C.; Fiates, G.M.R. Children’s influence over family food purchases of ultra processed foods: Interference of nutritional status. Mundo Saude 2015, 39, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer-Perez, E.I.; Musher-Eizenman, D. Children’s influence on parents: The bidirectional relationship in family meal selection. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 2974–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weems, G.H.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Collins, K.M.T. The role of reading comprehension in responses to positively and negatively worded items on rating scales. Eval. Res. Educ. 2006, 19, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sonderen, E.; Sanderman, R.; Coyne, J.C. Ineffectiveness of reverse wording of questionnaire items: Let’s learn from cows in the rain. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, T.; Schönberger, G. Eating food we dislike? Situations and reasons for eating distasteful food against personal preferences. Ernahrungs Umsch. 2015, 62, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, U.X.T.; Chambers, E., IV. Motivations for meal and snack times: Three approaches reveal similar constructs. Food Qual. Pref. 2018, 68, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, J.; Lewis, J.R. When designing usability questionnaires, does it hurt to be positive? In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 7 May 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 2215–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.J. Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M.S.; Oliver, M.; Simnadis, T.; Beck, E.J.; Coltman, T.; Iverson, D.; Caputi, P.; Sharma, R. The theory of planned behaviour and dietary patterns: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachan, R.R.C.; Conner, M.; Taylor, N.J.; Lawton, R.J. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 5, 97–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Australia | China | Japan | Mexico | Peru | Russia | Spain | Thailand | UK | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.00 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 49.8 | 49.8 |

| Male | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.00 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.2 | 50.2 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 18–34 years old | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.2 |

| 35–54 years old | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.5 |

| 55 years old or older | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 |

| Education (Highest Degree) | ||||||||||

| Primary school or less | 3.7 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.32 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 12.9 | 1.3 |

| High School | 36.2 | 20.6 | 33.2 | 4.13 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 42.4 | 12.5 | 26.0 | 45.4 |

| College/Univ. grad. | 60.2 | 78.7 | 64.8 | 95.6 | 90.3 | 91.1 | 53.0 | 85.7 | 61.1 | 53.3 |

| Number of Adult(s) in Household | ||||||||||

| 1 | 21.0 | 2.2 | 17.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 11.8 | 0.2 | 11.4 | 19.5 | 21.0 |

| 2 | 54.9 | 20.5 | 35.7 | 5.7 | 3.3 | 51.9 | 9.8 | 18.9 | 55.9 | 54.9 |

| 3 | 14.6 | 51.8 | 24.8 | 40.2 | 29.4 | 21.9 | 50.5 | 22.4 | 15.1 | 14.6 |

| 4 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 15.6 | 22.1 | 22.2 | 10.0 | 23.0 | 28.1 | 6.8 | 6.2 |

| 5 | 3.3 | 13.0 | 6.7 | 17.6 | 23.7 | 4.4 | 13.8 | 19.2 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.0 | 20.6 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Number of Child(ren) in Household | ||||||||||

| 0 | 66.5 | 42.5 | 75.1 | 37.8 | 39.4 | 51.8 | 58.4 | 47.8 | 63.7 | 66.5 |

| 1 | 17.3 | 50.3 | 16.8 | 28.4 | 27.0 | 26.8 | 25.9 | 30.2 | 16.8 | 17.3 |

| 2 | 11.9 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 25.6 | 23.0 | 17.5 | 13.5 | 17.0 | 14.0 | 11.9 |

| 3 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 6.0 | 8.3 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 3.7 |

| 4 or more | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.6 |

| General Health Interest | ||

| 1 | I am very particular about the healthiness of food | |

| 2 | I always follow a healthy and balanced diet | |

| 3 | It is important for me that my diet is low in fat | |

| 4 | It is important for me that my daily diet contains a lot of vitamins and minerals | |

| 5 | R * | I eat what I like, and I do not worry much about the healthiness of food |

| 6 | R | I do not avoid foods, even if they may raise my cholesterol |

| 7 | R | The healthiness of food has little impact on my food choices |

| 8 | R | The healthiness of snacks makes no difference to me |

| Pleasure | ||

| 9 | R | I do not believe that food should always be a source of pleasure |

| 10 | R | The appearance of food makes no difference to me |

| 11 | I need to eat delicious food on weekdays as well as weekends | |

| 12 | When I eat, I concentrate on enjoying the taste of food | |

| 13 | R | I finish my meal even when I do not like the taste of a food |

| 14 | An essential part of my weekend is eating delicious food | |

| Age | Mean ± std | Grouping | F Value | Pr (>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Health Interest | 18–34 years old | 4.50 ± 1.07 | c | 62.8 | <0.001 |

| 35–54 years old | 4.71 ± 1.10 | b | |||

| 55 years old or older | 4.88 ± 1.08 | a | |||

| Pleasure | 18–34 years old | 5.18 ± 0.92 | b | 12.4 | <0.001 |

| 35–54 years old | 5.27 ± 0.91 | a | |||

| 55 years old or older | 5.13 ± 0.98 | b |

| Education (Highest Degree Awarded) | Mean ± std | Grouping | F Value | Pr (>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Health Interest | College or University graduate | 4.77 ± 1.05 | a | 36.36 | <0.001 |

| High School | 4.51 ± 1.17 | b | |||

| Primary school or less | 4.46 ± 1.21 | b | |||

| Pleasure | College or University graduate | 5.24 ± 0.94 | a | 19.88 | <0.001 |

| High School | 5.10 ± 0.91 | b | |||

| Primary school or less | 4.93 ± 0.95 | c |

| Number of Adult(s) in Household | Mean ± std | Grouping | F Value | Pr (>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Health Interest | 1 | 4.52 ± 1.23 | c | 8.12 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 4.65 ± 1.10 | b | |||

| 3 | 4.75 ± 1.08 | ab | |||

| 4 | 4.70 ± 1.05 | b | |||

| 5 | 4.85 ± 1.01 | a | |||

| 6 | 4.75 ± 1.03 | ab | |||

| Pleasure | 1 | 5.01 ± 0.97 | e | 15.8 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 5.13 ± 0.94 | d | |||

| 3 | 5.24 ± 0.93 | c | |||

| 4 | 5.22 ± 0.93 | cd | |||

| 5 | 5.35 ± 0.90 | b | |||

| 6 | 5.45 ± 0.86 | a |

| Number of Child(ren) in Household | Mean ± std | Grouping | F Value | Pr (>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Health Interest | 0 | 4.67 ± 1.13 | – | 1.96 | 0.098 |

| 1 | 4.76 ± 1.03 | – | |||

| 2 | 4.70 ± 1.05 | – | |||

| 3 | 4.69 ± 1.11 | – | |||

| 4 or more | 4.67 ± 1.17 | – | |||

| Pleasure | 0 | 5.10 ± 0.96 | b | 21.12 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 5.32 ± 0.89 | a | |||

| 2 | 5.33 ± 0.91 | a | |||

| 3 | 5.30 ± 0.88 | a | |||

| 4 or more | 5.06 ± 1.00 | b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, C.; Chambers, E., IV; Lee, J. A Cross-Cultural Study of Health Interests and Pleasure by Consumers in 10 Countries. Foods 2025, 14, 3615. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213615

Pan C, Chambers E IV, Lee J. A Cross-Cultural Study of Health Interests and Pleasure by Consumers in 10 Countries. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3615. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213615

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Chunxiao, Edgar Chambers, IV, and Jeehyun Lee. 2025. "A Cross-Cultural Study of Health Interests and Pleasure by Consumers in 10 Countries" Foods 14, no. 21: 3615. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213615

APA StylePan, C., Chambers, E., IV, & Lee, J. (2025). A Cross-Cultural Study of Health Interests and Pleasure by Consumers in 10 Countries. Foods, 14(21), 3615. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213615