1. Introduction

Eggshell cracks significantly compromise both the visual quality and structural integrity of eggs, leading to moisture loss, nutrient degradation, and increased risk of microbial contamination (e.g.,

Salmonella). Such defects not only shorten shelf life and reduce commercial value, but may also cause food safety incidents [

1,

2]. Current eggshell crack detection methods mainly include manual inspection, acoustic techniques, and machine vision. However, manual inspection is prone to subjective bias and fatigue, resulting in low efficiency and low speed [

3]; acoustic detection is susceptible to interference from industrial vibrations and noise, and it may cause secondary damage [

4]; although machine vision offers high speed, its ability to detect invisible or micro-scale cracks, especially under varying shell colors, dirt contamination, and changing lighting conditions [

5].

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) technology captures sequential spectral reflectance at each pixel, enabling simultaneous analysis of the composition and structural characteristics of the target material. This “joint spectral-spatial feature extraction” characteristic makes HSI highly sensitive to micro-cracks on eggshells. In crack regions, stress concentration and microstructural damage alter the local optical properties (reflection, absorption, and transmission), resulting in shifts in reflectance at specific wavelengths or changes in spectral shape. Consequently, even cracks that are nearly invisible under visible light can be detected in the near-infrared or short-wave infrared region [

6]. Previous studies have shown that HSI outperforms conventional RGB imaging in agricultural product defect detection, offering significant advantages in both accuracy and robustness [

7,

8]. For instance, Huang et al. (2021) integrated hyperspectral spectral features with texture features in nectarine quality assessment [

9]. Using a Least Squares Support Vector Machine model, they achieved simultaneous identification of external defects and prediction of soluble solids content [

9]. Xu et al. (2023) integrated HSI in the range of 866.4–1701 nm with an attention-based convolutional neural network to classify corn seed defects, reaching over 90% accuracy with the optimal model [

10]. In the field of non-destructive detection of eggshell cracks, Ahmed et al. systematically reviewed recent advances in optical sensing technologies for the egg industry and emphasized the potential of combining HSI with deep learning to improve crack detection accuracy and enable automated grading [

11]. Yao et al. proposed a method that captures images at different wavelengths via HSI to detect cracked eggshells; however, crack tips that are too thin remain difficult to detect due to minimal brightness contrast with surrounding areas [

12]. Han et al. employed visible–near-infrared spectroscopy for egg sorting and crack detection, finding that eggshell color differences significantly affect spectral data acquisition, with the high reflectance of white shells causing spectral information loss and reduced detection accuracy [

13]. Chen et al. integrated HSI with band selection and deep learning algorithms to develop the HEDIT system, capable of real-time operation on production lines [

14]. So et al. utilized visible–near-infrared surface HSI to capture multi-dimensional spectral data from both the eggshell surface and interior. By combining multivariate analysis with pattern recognition algorithms, they realized non-destructive and high-precision microcrack detection, providing crucial technical support for replacing manual inspection and enhancing automated grading [

15].

Although HSI combined with machine learning or shallow neural networks can achieve object-level localization of eggshell cracks, such coarse detection remains inadequate for industrial grading applications. Accurate quality control requires not only identifying the presence of cracks but also evaluating their severity, spatial extent, and distinction from surface artifacts (e.g., blood spots and calcification lines). These objectives can only be fulfilled through pixel-level segmentation, which enables precise delineation of crack boundaries and regions, and provides morphological details that serve as quantitative evidence for grading and safety evaluation—information that object-level localization cannot deliver. Despite these advances, several key challenges remain. Variations in shell color and complex backgrounds often lead to feature confusion and missed detections. Shallow models relying on hand-crafted features struggle to integrate joint spectral-spatial feature extraction and to represent the subtle characteristics of microcracks. Furthermore, the high-dimensional and nonlinear nature of hyperspectral data frequently results in information loss in shallow or single-task models, thereby constraining detection sensitivity and overall accuracy.

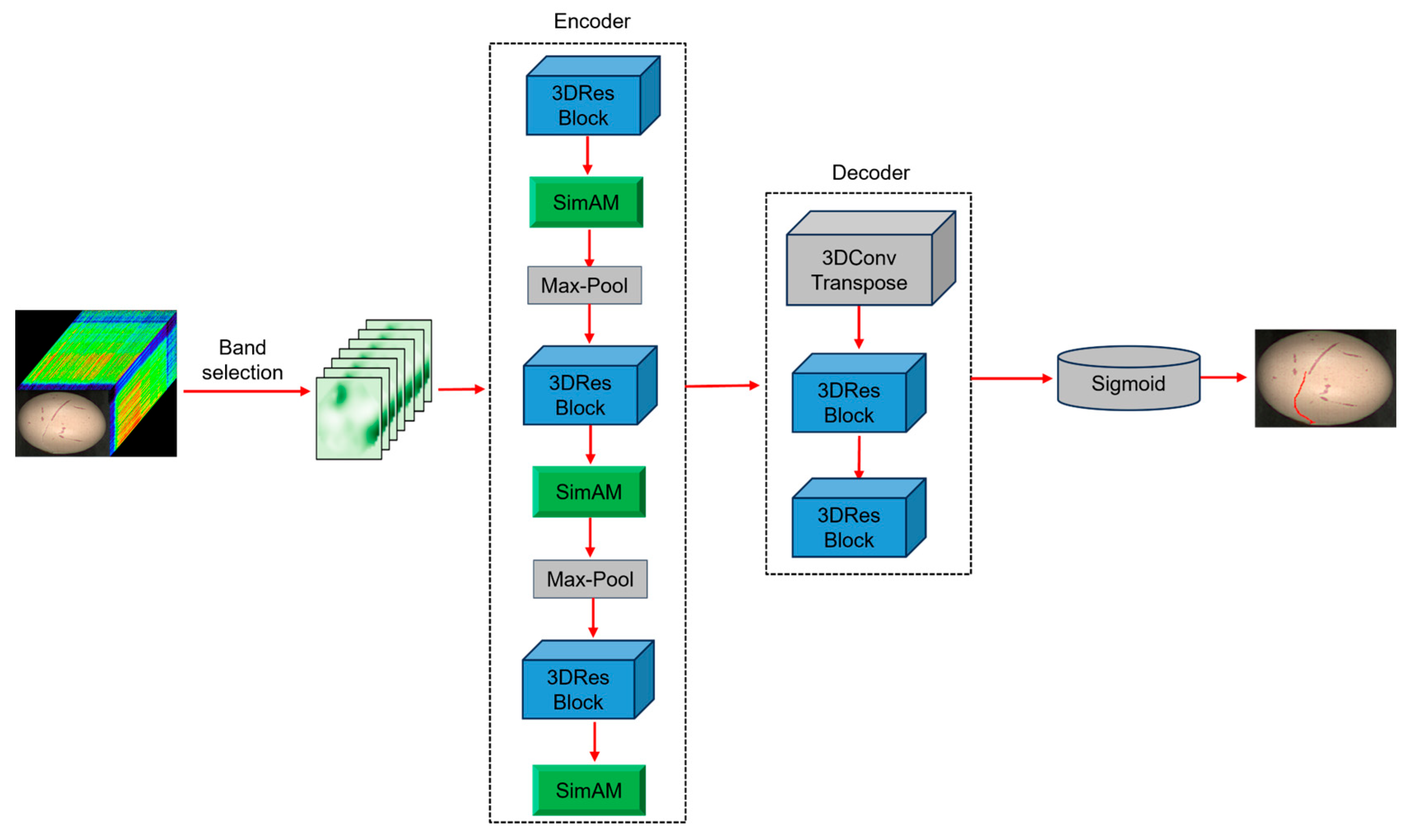

With the advancement of deep learning, three-dimensional convolutional neural networks (3D-CNNs) have shown advantages in hyperspectral image analysis as they can simultaneously process spatial and spectral information. 3D-CNNs enhance the detection of minute defects while preserving spectral continuity and spatial texture features. Li et al. systematically reviewed 3D-CNN-based hyperspectral image classification approaches, emphasizing their advantage in spectral–spatial feature extraction [

16]. Compared with one-dimensional or two-dimensional CNNs, 3D-CNNs significantly reduce information loss and perform excellently in detecting subtle defects such as plant disease identification [

17]. Zhang et al. incorporated 3D-CNN and deformable convolution in agricultural product crack detection, further optimizing spectral feature processing to suit the detection of subtle defects such as produce cracks [

18]. However, in eggshell crack detection, the standard 3D-CNN still faces limitations: complex background noise, shell color variation, and gradient vanishing or feature degradation as network depth increases, all of which reduce detection accuracy.

To address these issues, this paper proposes a non-destructive eggshell crack detection method that integrates HSI with an improved 3D-CNN to fully exploit joint spectral–spatial features, thereby addressing the limitations of conventional methods in microcrack recognition. Specifically, within the 3D-CNN framework, we incorporate a lightweight SimAM attention mechanism to enhance the response to key spectral–spatial crack regions while suppressing background noise. Additionally, residual modules are adopted to replace standard convolution layers, mitigating gradient attenuation and feature degradation in deeper networks and thus balancing detection accuracy with computational efficiency. Experimental results under varied shell colors and complex background conditions confirm that the proposed method achieves high-precision crack detection and accurate localization, offering a feasible technical pathway for online egg quality grading and intelligent inspection.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Spectral Feature Analysis of Intact and Cracked Targets

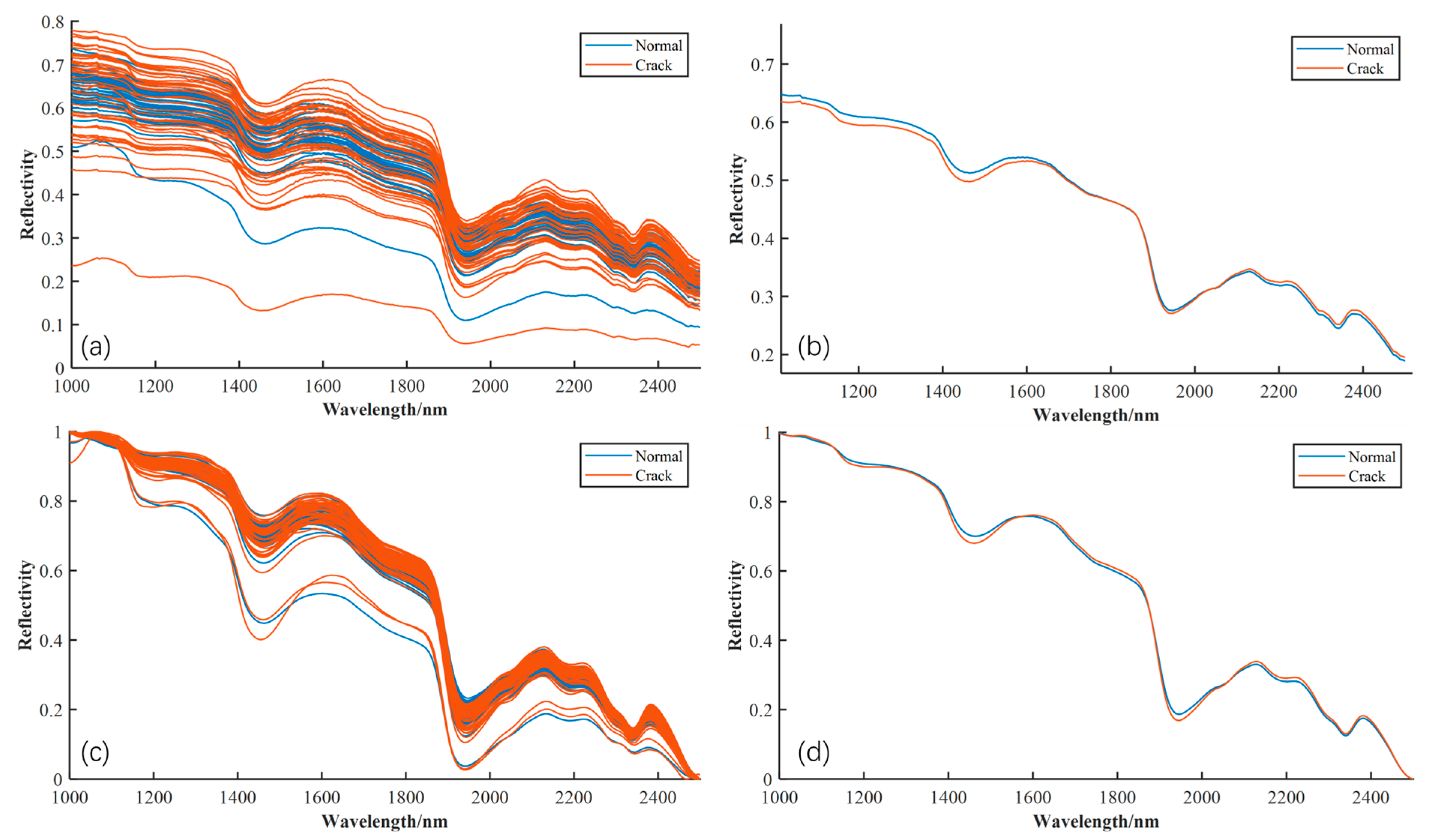

A systematic analysis of hyperspectral reflectance data from cracked and intact eggshell regions was conducted.

Figure 7a illustrates the raw spectral curves for the two sample types in the 1000–2500 nm wavelength range. As observed, the raw data exhibit baseline drift and scattering effects, leading to considerable intra-class variation. To highlight the overall trend, the mean spectra for each class were calculated, as shown in

Figure 7b. The spectral shapes demonstrate high consistency with significant overlap, with only slight variations in reflectance intensity. Specifically, cracked eggshells generally exhibit lower reflectance than intact eggshells, yet the overall spectral pattern remains consistent across all bands. To enhance spectral quality and accentuate subtle differences, the raw spectral data were pre-processed using the Savitzky–Golay (SG) smoothing algorithm, combined with Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) [

25,

26]. The results of this preprocessing are shown in

Figure 7c, where the spectral curves are more compact and concentrated. This indicates that the preprocessing method effectively reduces baseline drift, scattering effects, and other non-chemical interferences. As a result, the mean spectral curve in

Figure 7d is smoother and more standardized.

From a biochemical perspective, spectral characteristics at different wavelengths are closely tied to the primary chemical constituents of the eggshell and its underlying structures. Considering that the average eggshell thickness is approximately 0.30–0.40 mm, the incident near-infrared light (1000–2500 nm) exhibits sufficient penetration depth to pass through the calcified layer and interact with the shell membrane and outer albumen [

27,

28]. Consequently, the recorded spectra represent a composite signal of the shell and subsurface components. Previous studies have demonstrated that the absorption valleys near 1450 nm and 1940 nm correspond to the first and second overtone water absorption bands [

29,

30], which are detectable due to the presence of bound moisture in the underlying organic membrane and albumen. Although the calcified shell itself contains limited water, micro-cracks may increase the optical contribution of the exposed membrane, thereby influencing reflectance in these bands. Furthermore, the region between 2100 and 2300 nm has been linked to combination absorptions of C=O and N–H functional groups associated with the protein-rich eggshell membrane [

31]. Micro-cracks can alter the scattering path and partially expose this membrane material, resulting in subtle spectral differences within this range. Additionally, near-infrared scattering features related to the crystalline CaCO

3 structure may also be affected by microstructural disruption of the shell.

Despite the preprocessing, the spectral curves of both classes still exhibit significant overlap across most wavelengths, indicating weak separability. Despite the preprocessing, the spectral curves of both classes still exhibit significant overlap across most wavelengths, indicating weak separability. The main challenge in hyperspectral crack detection lies in the high spectral redundancy across the broad 1000–2500 nm wavelength range, where adjacent bands are strongly correlated, with many contributing minimally to biochemical discrimination. This redundancy in-creases the computational complexity of data processing and model training and can obscure subtle spectral variations caused by cracks.

4.2. Feature Band Extraction and Performance Analysis for Crack Detection

Given the spectral redundancy and weak separability identified in

Section 4.1, three feature band selection methods—CARS, SPA, and RF—were applied to reduce dimensionality, mitigate multicollinearity, and enhance crack detection performance.

- (1)

Feature Band Selection Using the CARS Algorithm

For the CARS algorithm, the number of iterations was set to 50, and the sampling ratio was set to 0.8. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the feature selection process significantly reduces the number of wavelengths. In

Figure 8a, the initial count of approximately 280 wavelengths rapidly decreases as iterations progress, indicating the efficient removal of redundant and irrelevant features.

Figure 8b shows that the RMSECV, calculated via Monte Carlo cross-validation (MCCV), decreases steadily until reaching a minimum at the 30th iteration, suggesting optimal predictive performance at this point. After the 30th iteration, the RMSECV slightly increases as some critical features are inadvertently discarded. The regression coefficients in

Figure 8c confirm that the 30th iteration marks the optimal selection, resulting in the identification of 15 key wavelengths.

- (2)

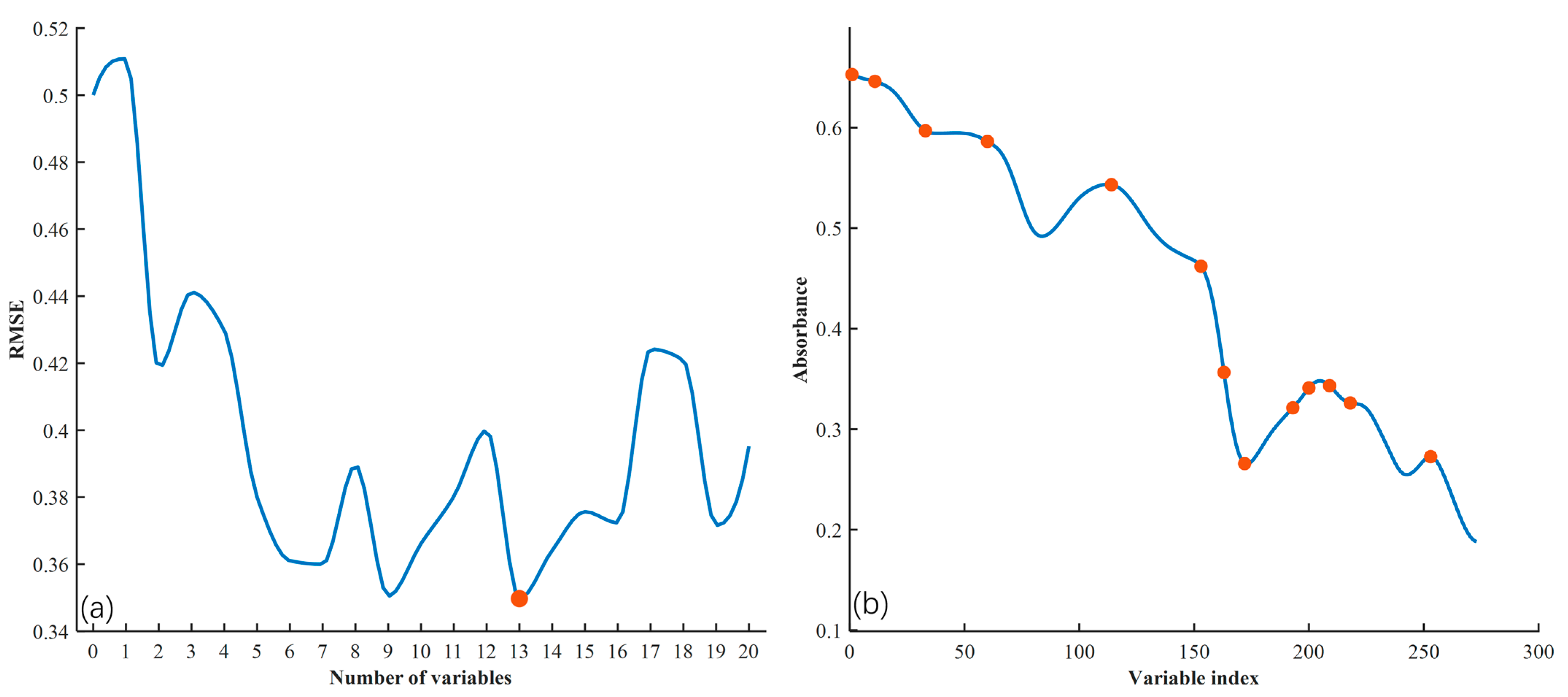

Feature Band Selection Using the SPA Algorithm

For the SPA algorithm, the maximum number of wavelengths was set to 20. As shown in

Figure 9a, the RMSE value decreases sharply at first as more wavelengths are added, then plateaus, indicating the elimination of redundant information. For the SG + MSC preprocessed spectral data, 13 key wavelengths were selected, achieving the lowest RMSE and optimal predictive accuracy, as shown in

Figure 9b. These 13 wavelengths cover multiple crucial regions of the spectrum, providing a comprehensive representation of the samples’ spectral characteristics.

- (3)

Feature Band Selection Using the RF Algorithm

The RF algorithm obtains the selection probability distribution of each wavelength variable through multiple iterations of sampling (

Figure 10). The horizontal axis represents the full-spectrum wavelength index, while the vertical axis denotes the probability of a variable being selected. To identify highly important bands, a selection probability threshold of 0.2 was set, with variables exceeding this threshold considered to be strongly correlated with the modeling objective. The RF method ultimately selected 23 key wavelengths, providing an alternative feature selection approach.

- (4)

Method Comparison and Performance Evaluation

To evaluate the effectiveness of the three feature selection methods, the selected wavelengths from CARS, SPA, and RF were used as model inputs and compared with the full-band input. The results, summarized in

Table 1, demonstrate that the CARS method outperforms all other methods across all evaluation metrics. Specifically, the IoU and F1 scores for CARS reached 59.99% and 74.99%, respectively—an improvement of approximately 8.2% and 6.8% over the full-band input—while reducing training time to 35.5 min. Despite a reduction of over 90% in data dimensionality, CARS maintained or even improved segmentation performance, effectively eliminating noise and redundancy while preserving the most discriminative features. In contrast, while the SPA method offers a training efficiency advantage, its accuracy metrics are slightly lower than those of CARS. The RF method performed well in terms of Precision but had a low Recall, resulting in overall performance inferior to both CARS and SPA. The full-band input method achieved the lowest scores across all metrics and incurred significantly higher training costs. In conclusion, similar to the spectral feature analysis in

Section 4.1, the results from this feature band selection process demonstrate that the CARS method strikes the optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency. Therefore, the feature bands selected by CARS were adopted as model inputs for all subsequent experiments.

4.3. Ablation Experiment

To evaluate the individual contributions of the core components—3D-ResBlock and the SimAM attention mechanism—in the proposed 3D-CrackNet model, a comprehensive ablation study was conducted. A standard 3D-CNN served as the baseline. The performance impact of each component was assessed by progressively integrating them into the baseline model. All models were trained and tested under identical conditions using the 15 feature bands selected by the CARS method. To statistically validate the performance improvements, a paired t-test was performed on the evaluation metrics (IoU, Precision, Recall, F1-score) obtained from five independent runs of each model configuration. The results are summarized in

Table 2.

The baseline 3D-CNN model achieved IoU, Precision, Recall, and F1-score values of 52.08%, 71.09%, 66.07%, and 68.49%, respectively, serving as a reference for subsequent performance improvements. With the integration of the SimAM attention mechanism, the IoU increased to 53.95%, and Precision rose to 72.70%. Statistical analysis confirmed that the improvement in Precision was statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating that this mechanism effectively enhances feature representation and spatial dependency modeling, thereby improving feature extraction performance. When the ResBlock module was incorporated, the IoU improved to 56.77%, and the F1-score increased to 72.42%. Both of these improvements were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05), demonstrating its positive effect in strengthening deep feature propagation and mitigating gradient vanishing. By integrating both SimAM and ResBlock to form the complete 3D-CrackNet model, overall performance reached its peak: IoU, Precision, Recall, and F1-score achieved 60.62%, 75.09%, 75.89%, and 75.49%, respectively. These represent improvements of 8.54%, 4%, 9.82%, and 7% over the baseline model. All of these improvements over the baseline model were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Despite the increase in model parameters and training time, the performance gains significantly outweighed the additional computational cost, reflecting the model’s rational and efficient design. In conclusion, the ablation results fully demonstrate the complementarity and critical roles of ResBlock and SimAM. The complete 3D-CrackNet model significantly outperforms other combinations of components in terms of accuracy, recall, and overall performance, achieving an excellent balance between performance improvement and computational complexity. This validates the effectiveness and practical value of the proposed model for hyperspectral egg crack segmentation tasks.

4.4. Comparative Experiment

To further validate the structural advantages of 3D-CrackNet in spatial–spectral feature extraction and crack detection, a series of comparative experiments were conducted with several representative convolutional neural network models as benchmarks. All models used the 15 feature bands selected by the CARS method as input, and training environments, hyperparameter settings, and data preprocessing were kept consistent. The 1D-CNN model classified solely based on pixel-level spectral vectors, ignoring spatial contextual features. The 2D-CNN model took single-band images as input and relied on spatial information, but it almost entirely lost spectral dimension features. The 3D-CNN (baseline) model jointly leveraged spatial and spectral information to achieve integrated spatial–spectral modeling. Building upon the 3D-CNN, the proposed 3D-CrackNet model incorporates a ResBlock and the SimAM attention mechanism to further enhance spatial–spectral feature representation.

As shown in the training curves (

Figure 11), 3D-CrackNet converges to a stable and significantly higher F1-score (approximately 0.75) after about 25 epochs, while also exhibiting the most rapid loss reduction and the lowest final loss value. According to the quantitative results in

Table 3, the IoU of the 1D-CNN is only 29.29%, the lowest among all models, suggesting that relying solely on spectral information is insufficient for crack detection. With the incorporation of spatial information, the 2D-CNN shows a marked improvement over the 1D-CNN, achieving an IoU of 40.37% and an F1-score of 57.33%. However, due to the absence of spectral dimension features, it still suffers from significant limitations. The 3D-CNN, which simultaneously leverages spatial and spectral information, significantly outperforms the previous two models, attaining an IoU of 52.51% and an F1-score of 68.86%. Building upon this, 3D-CrackNet achieves a further breakthrough, with IoU and F1-score increasing to 60.62% and 75.49%, respectively—representing improvements of 8.11% and 6.63% over the baseline 3D-CNN. These results place 3D-CrackNet’s performance among the leading results in deep learning-based crack detection.

The fundamental reason for the performance enhancement lies in the ResBlock’s ability to mitigate network degradation and strengthen deep feature propagation, while the SimAM attention mechanism allows the model to focus on small crack regions, thereby significantly improving its capability to detect subtle defects. Based on the comparative results and training curve analysis, it is evident that 3D-CrackNet demonstrates significant advantages in joint spatial–spectral feature representation and crack segmentation tasks using hyperspectral data, surpassing common CNN models in both accuracy and stability. This fully validates its effectiveness and feasibility for practical applications.

4.5. Visualization Analysis of Crack Detection Results

To visually evaluate the performance of the enhanced 3D-CrackNet model in egg crack detection tasks, representative samples were selected for comparative visualization analysis. The comparison involved three models: the 1D-CNN, which relies solely on spectral information, and the 2D-CNN, which utilizes only spatial information. The results are shown in

Figure 12, where green lines represent the true crack positions (Ground Truth), and red regions denote the predicted outputs of each model. To provide a quantitative reference for these visual comparisons, the instance-level F1-score and Intersection over Union (IoU) metrics for each prediction are annotated at the bottom of the corresponding sub-images.

As observed in the figure, the 1D-CNN, which depends exclusively on spectral information, struggles to capture spatial structural features. It tends to produce incomplete detections and false alarms, particularly for slender and low-contrast cracks, often misclassifying background spots as cracks.(e.g., resulting in a low IoU of 0.2301 for the spotted egg in the second row) The 2D-CNN, by leveraging spatial context, depicts crack shapes more accurately; however, due to its neglect of fine-grained spectral features, it fails to detect smaller cracks and generates false positives in regions with complex textures. The 3D-CNN model, which integrates both spectral and spatial information, shows clear improvements over both the 1D-CNN and 2D-CNN, yet some missed and false detections still remain. In contrast, the 3D-CrackNet model effectively integrates multi-dimensional information through joint spatial–spectral modeling, which is crucial for distinguishing structural cracks from superficial interferences. The ResBlock module ensures stable deep feature propagation, while the SimAM attention mechanism dynamically weights discriminative spectral–spatial characteristics, thereby specifically enhancing crack-related features and suppressing responses from irrelevant background variations such as stains and natural shell textures. Quantitative analysis of the representative samples displayed in

Figure 12 further confirms these visual observations. Specifically, for challenging scenarios with complex spotted backgrounds (Row 2), while the comparative models struggled with IoUs below 0.45, 3D-CrackNet achieved a remarkable IoU of 0.8478 and an F1-score of 0.9176. Across all displayed samples, the proposed model consistently maintained high metric scores (e.g., F1 > 0.68 and IoU > 0.51), significantly outperforming the baseline models. As a result, the predictions exhibit optimal performance in terms of crack contour integrity, positional accuracy, and robustness against false positives caused by non-crack regions. The model successfully segments fine cracks while effectively avoiding the misclassification of eggshell spots, stains, or texture patterns as cracks, demonstrating a clear advantage in handling real-world variability.

In summary, the visualization results in

Figure 12 clearly highlight the superiority of pixel-level segmentation. They not only validate the robustness and accuracy of 3D-CrackNet under complex background conditions but also underscore why precise pixel-wise delineation is essential for reliable and quantitative assessment of eggshell cracks—something that object-level detection alone cannot achieve. The visualization results corroborate the quantitative findings, demonstrating that 3D-CrackNet provides a robust and precise solution for automated, pixel-level egg crack inspection, which is essential for reliable quality assessment.

5. Discussion

This study addresses the application requirements of HSI in non-destructive egg crack detection by proposing the 3D-CrackNet model, which integrates feature band selection, deep spatial–spectral fusion, and a lightweight attention mechanism for high-precision recognition of fine cracks. Comprehensive experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method substantially improves detection accuracy, robustness, and generalization capability compared to existing models. These findings not only validate the effectiveness of individual techniques but also highlight several key scientific challenges and technical principles involved in integrating hyperspectral data with deep learning models for agricultural and food inspection applications.

At the dataset level, hyperspectral imagery, despite its rich spectral information, faces challenges such as high-dimensional redundancy, noise sensitivity, and the “curse of dimensionality.” These issues make the rational selection of feature bands critical to model performance. In this study, dimensionality reduction was achieved using the CARS algorithm, which retained spectral channels strongly correlated with crack defects, thus improving both computational efficiency and recognition accuracy. This indicates that data-driven feature compression is not only an effective means for algorithm acceleration but also crucial for enhancing a model’s generalization ability. In future efforts to construct larger-scale, multi-variety, and multi-condition datasets, band selection and feature refinement will remain central steps for improving model stability and performance.

At the methodological level, 3D-CrackNet demonstrates the efficacy of joint spatial–spectral modeling for crack detection. Traditional classification methods such as Botta et al. [

5] achieve high accuracy by making a single binary decision per egg. In contrast, 3D-CrackNet performs pixel-wise segmentation—a more challenging task that requires precise localization of crack boundaries. Although the pixel-wise F1-score (75.49%) is numerically lower than classification accuracy, it provides critical morphological information (e.g., crack dimensions and location) essential for industrial grading. This capability allows differentiation between cosmetic and structural cracks, which binary classification cannot achieve. Thus, while direct metric comparison may be misleading, the proposed method offers superior utility for fine-grained quality control in practical applications.

At the application level, the proposed method provides technical support for automated, non-destructive egg crack detection. Compared with traditional manual inspection or single optical methods, the hyperspectral imaging–deep learning combined approach significantly enhances detection consistency and objectivity. While the current model performs excellently in laboratory settings, further optimization is required in terms of computational efficiency, hardware compatibility, and real-time processing capabilities to meet the demands of large-scale industrial production. Furthermore, to achieve industrial-grade full-shell inspection, the proposed method can be extended to a multi-view system, for instance, by employing a rotary mechanism or a multi-camera array for data acquisition. The core algorithm of this study, 3D-CrackNet, is well-suited for processing multi-view data. The primary subsequent challenge will focus on the fusion of multi-view segmentation results and the generation of a comprehensive defect map.

Finally, while hyperspectral imaging provides rich spectral information, its deployment in industrial production lines may be constrained by hardware cost, system integration complexity, and the need for high-speed acquisition modules. Furthermore, industrial grading requires continuous inspection on conveyor belts, necessitating a total processing time per egg that is significantly faster than achieved here. Although the core 3D-CrackNet model inference shows promise with a latency of approximately 0.9 s, future work must focus on developing a synchronized, high-throughput pipeline. This entails integrating high-speed cameras, real-time preprocessing hardware (e.g., FPGAs), and further model optimization to bridge the gap between laboratory proof-of-concept and commercial-scale application. These factors should be considered when translating the proposed approach into large-scale commercial applications.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a non-destructive egg crack detection method based on HSI and the improved 3D-CrackNet model, which integrates the CARS algorithm for feature band selection, a 3D residual module, and the SimAM attention mechanism. The CARS algorithm effectively reduced dimensionality, retaining 15 key bands that enhanced detection accuracy and computational efficiency. Experimental results demonstrate that 3D-CrackNet outperforms 1D-CNN, 2D-CNN, and conventional 3D-CNN models, achieving an F1-score of 75.49% and an IoU of 60.62%. Ablation studies confirmed that the integration of ResBlock and SimAM significantly improved model performance, particularly in fine crack detection under complex backgrounds.

These findings highlight the potential of HSI and deep learning for automated, high-precision crack detection in agricultural products. Future work will focus on further model optimization for real-time industrial application and expanding the detection capabilities to multiple defect categories.