Impact of Climate Change on the Presence of Ochratoxin A in Red and White Greek Commercial Wines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wine Sampling

2.2. Physicochemical Analyses of the Wine

2.3. Sample Preparation and Mycotoxin Extraction of Wine Samples

2.4. Chromatographic Separation

2.5. Method Validation

2.6. Meteorological Data

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Characteristics of the Wine Producing Area

3.2. Assessment of Mycotoxin Contamination Levels in Red and White Wines

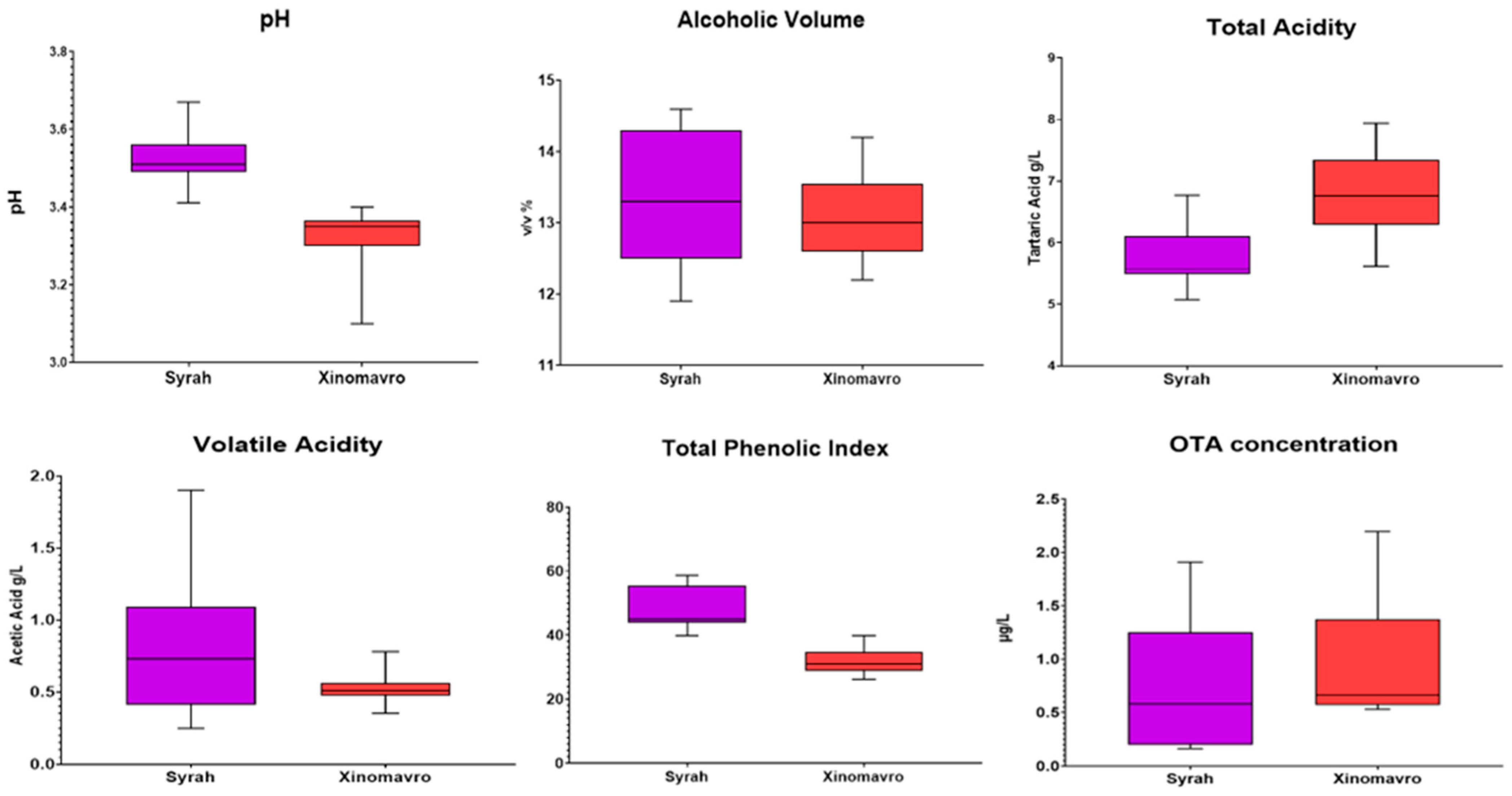

3.3. Conventional Wine Analysis and OTA Levels

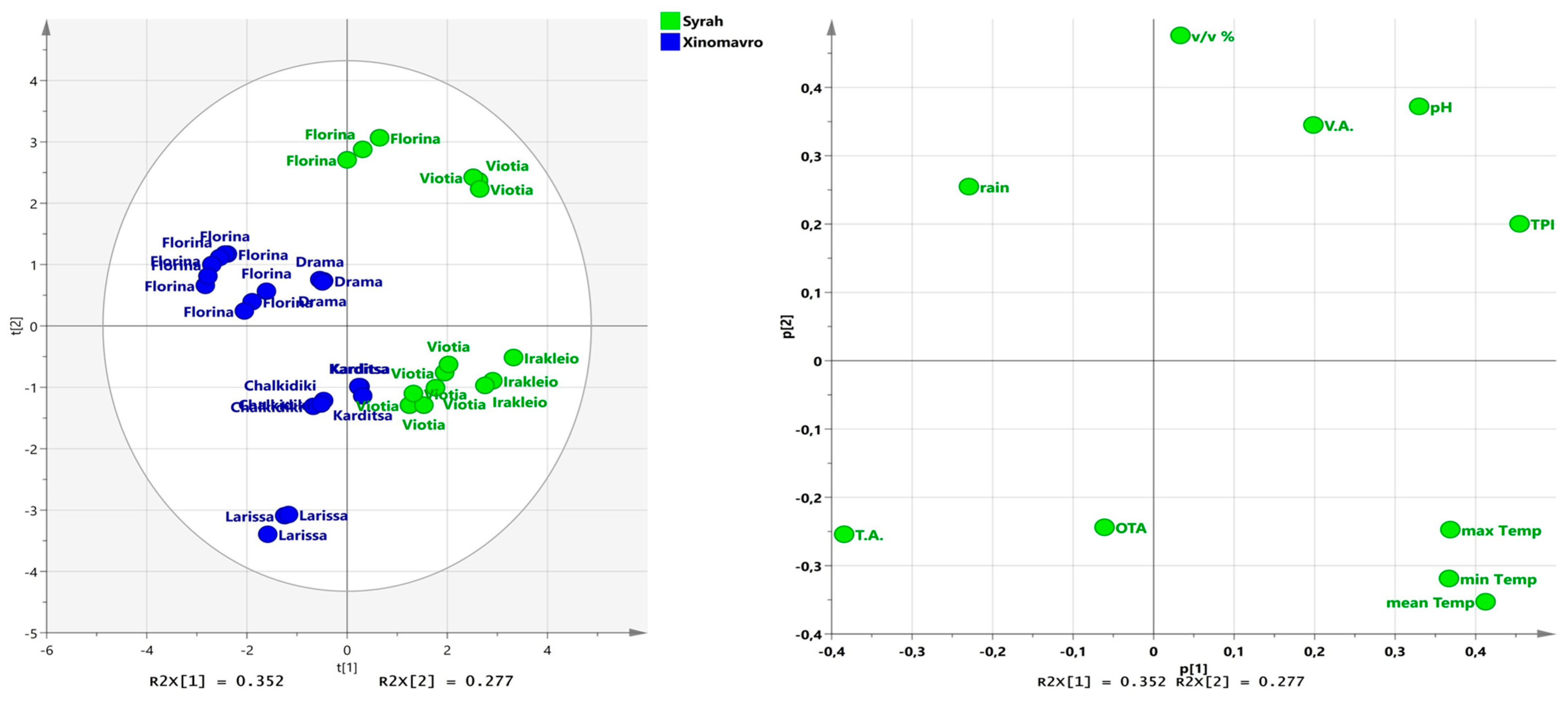

3.4. Principal Component Analysis

3.5. Correlation Between the Occurrence of OTA and Meteorological Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO-OIV. 2019 Statistical Report on World Vitiviniculture; Table and Dried Grapes; OIV Statistical Unit, International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV): Paris, France, 2019; pp. 1–23. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/6782/oiv-2019-statistical-report-on-world-vitiviniculture.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Freire, L.; Passamani, F.R.F.; Thomas, A.B.; Nassur, R.D.C.M.R.; Silva, L.M.; Paschoal, F.N.; Pereira, G.E.; Prado, G.; Batista, L.R. Influence of physical and chemical characteristics of wine grapes on the incidence of Penicillium and Aspergillus fungi in grapes and ochratoxin A in wines. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Serna, J.; Vázquez, C.; González-Jaén, M.T.; Patiño, B. Wine contamination with ochratoxins: A review. Beverages 2018, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K. Occurrence of ochratoxin A in commodities and processed food–A review of EU occurrence data. Food Addit. Contam. 2005, 22 (Suppl. S1), 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Reports on Tasks for Scientific Cooperation. Report of Experts Participating in Task 3.2.7. Assessment of Dietary Intake of Ochratoxin A by the Population of EU Member States. Directorate-General Health and Consumer Protection. 2002. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-10/cs_contaminants_catalogue_ochratoxin_task_3-2-7_en.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Zimmerli, B.; Dick, R. Ochratoxin A in table wine and grape-juice: Occurrence and risk assessment. Food Addit. Contam. 1996, 13, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellí, N.; Bau, M.; Marín, S.; Abarca, M.L.; Ramos, A.J.; Bragulat, M.R. Mycobiota and ochratoxin A producing fungi from Spanish wine grapes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 111, S40–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, R.R.M.; Venâncio, A.; Lima, N.; Guilloux-Bénatier, M.; Rousseaux, S. Predominant mycotoxins, mycotoxigenic fungi and climate change related to wine. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anli, E.; Bayram, M. Ochratoxin A in wines. Food Rev. Int. 2009, 25, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasram, S.; Mani, A.; Zaied, C.; Chebil, S.; Abid, S.; Bacha, H.; Mliki, A.; Ghorbel, A. Evolution of ochratoxin A content during red and rose vinification. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilani, P.; Magan, N.; Logrieco, A. European research on ochratoxin A in grapes and wine. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 111, S2–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintela, S.; Villarán, M.C.; López de Armentia, I.; Elejalde, E. Ochratoxin A removal in wine: A review. Food Control 2013, 30, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, A.; Atoui, A. Ochratoxin A: General Overview and Actual Molecular Status. Toxins 2010, 2, 461–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Some Naturally Occurring Substances: Food Items and Constituents, Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines and Mycotoxins. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; IARC: Lyon, France, 1993; Volume 56, pp. 489–521. Available online: https://publications.iarc.fr/_publications/media/download/1901/a815bd2f53a323de205a5e997377bc38cc80e4b9.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) on a request from the Commission related to Ochratoxin A in Food, Question N° EFSA-Q-2005-154, Adopted on 4 April 2006. EFSA J. 2006, 365, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- IARC, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Risk Assessment and Risk Management of Mycotoxins. IARC Sci. Publ. 2012, 158, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, European Food Safety Authority. The Four Steps of Risk Assessment. EFSA Multimedia. 2025. Available online: https://multimedia.efsa.europa.eu/riskassessment/index.htm (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Annunziata, L.; Campana, G.; De Massis, M.R.; Aloia, R.; Scortichini, G.; Visciano, P. Ochratoxin A in Foods and Beverages: Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment. Expo. Health 2025, 17, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 (Text with EEA relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L119, 103. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/915/2025-01-01 (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Karsauliya, K.; Yahavi, C.; Pandey, A.; Bhateria, M.; Sonker, A.K.; Pandey, H.; Sharma, M.; Singh, S.P. Co-occurrence of mycotoxins: A review on bioanalytical methods for simultaneous analysis in human biological samples, mixture toxicity and risk assessment strategies. Toxicon 2022, 218, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzazzi-Fazeli, E.; Reiter, E.V. Sample preparation and clean up strategies in the mycotoxin analysis: Principles, applications and recent developments. In Determining Mycotoxins and Mycotoxigenic Fungi in Food and Feed; De Saeger, S., Ed.; Wood Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 37–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiani, A.; Corzani, C.; Arfelli, G. Correlation between different clean-up methods and analytical techniques performances to detect ochratoxin A in wine. Talanta 2010, 8, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Perez, J.F.; Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; Garcia-Campaña, A.M.; Gamiz-Gracia, L. Solid-phase extraction as sample treatment for the determination of ochratoxin A in foods: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 57, 3405–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taher, F.; Banaszewski, K.; Jackson, L.; Zweigenbaum, J.; Ryu, D.; Cappozzo, J. Rapid method for the determination of multiple mycotoxins in wines and beers by LC-MS/MS using a stable isotope dilution assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2378–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Manzares, N.; Garcia-Campaña, A.M.; Gamiz-Gracia, L. Comparison of different sample treatments for the analysis of ochratoxin A in wine by capillary HPLC with laser-induced fluorescence detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 2987–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño-Repizo, L.; Gargantini, R.; Manzano, H.; Raba, J.; Cerutti, S. Assessment of ochratoxin A occurrence in Argentine red wines using a novel sensitive QuEChERS-solid phase extraction approach prior to ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methodology. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 97, 2487–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzutti, I.R.; de Kok, A.; Scholten, J.; Righi, L.W.; Cardoso, C.D.; Rohers, G.N.; da Silva, R.C. Development, optimization and validation of a multimethod for the determination of 36 mycotoxins in wines by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 2014, 129, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Goodman, S.; van der Lee, P.; Xu, Z.; Fortunato, A.; Yang, P. The worlds of wine: Old, new and ancient. Wine Econ. Policy 2018, 7, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkouropoulos, G.; Miliordos, D.E.; Tsimbidis, G.; Hatzopoulos, P.; Kotseridis, Y. How to Improve a Successful Product? The Case of “Asproudi” of the Monemvasia Winery Vineyard. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliordos, D.E.; Merkouropoulos, G.; Kogkou, C.; Arseniou, S.; Alatzas, A.; Proxenia, N.; Hatzopoulos, P.; Kotseridis, Y. Explore the Rare—Molecular Identification and Wine Evaluation of Two Autochthonous Greek Varieties: “Karnachalades” and “Bogialamades”. Plants 2021, 10, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markaki, P.; Delpont-Binet, C.; Grosso, F.; Dragacci, S. Determination of Ochratoxin A in Red Wine and Vinegar by Immunoaffinity High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography. J. Food Prot. 2001, 64, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanaki, I.; Foufa, E.; Tsatsou-Dritsa, A.; Dais, P. Ochratoxin A concentrations in Greek domestic wines and dried vine fruits. Food Addit. Contam. 2003, 20, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufleros, E.H.; Tricard, C.; Bouloumpasi, E.C. Occurrence of ochratoxin A in Greek wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaha, M.J.; Metafa, M.; Lanaridis, P. Ochratoxin A occurrence in Greek dry and sweet wines. OENO One 2007, 41, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrinea, E.P.; Natskoulis, P.I.; Spiropoulos, A.E.; Magan, N.; Tassou, C.C. A survey of ochratoxin A occurrence in Greek wines. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2011, 4, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarigiannis, Y.; Kapolos, J.; Koliadima, A.; Tsegenidis, T.; Karaiskakis, G. Ochratoxin A levels in Greek retail wines. Food Control 2014, 42, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testempasis, S.I.; Kamou, N.N.; Papadakis, E.N.; Menkissoglu-Spiroudi, U.; Karaoglanidis, G.S. Conventional vs. organic vineyards: Black Aspergilli population structure, mycotoxigenic capacity and mycotoxin contamination assessment in wines, using a new Q-TOF MS-MS detection method. Food Control 2022, 136, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, C.L.; Bartley, A.; Welch, A.Z.; Berry, J.P. High Incidence and Levels of Ochratoxin A in Wines Sourced from the United States. Toxins 2018, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV). Compendium of International Methods of Analysis of Wines and Musts; OIV: Paris, France, 2025; Volume 1, Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/publication/2025-03/Compendium%20of%20MA%20Wine%20Complet%202025.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Lagouvardos, K.; Kotroni, V.; Bezes, A.; Koletsis, I.; Kopania, T.; Lykoudis, S.; Mazarakis, N.; Papagiannaki, K.; Vougioukas, S. The automatic weather stations network of the National Observatory of Athens (NOANN): Operation and database. Geosci. Data J. 2017, 4, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocking, A.D.; Leong, S.L.; Kazi, B.A.; Emmett, R.W.; Scott, E.S. Fungi and mycotoxins in vineyards and grape products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 119, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.L.; Hocking, A.D.; Pitt, J.I.; Kazi, B.A.; Emmett, R.W.; Scott, E.S. Australian research on ochratoxigenic fungi and ochratoxin A. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 111, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambuti, A.; Strollo, D.; Genovese, A.; Ugliano, M.; Ritieni, A.; Moio, L. Influence of enological practices on ochratoxin A concentration in wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2005, 56, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietri, A.; Bertuzzi, T.; Pallaroni, L.; Piva, G. Occurrence of ochratoxin A in Italian wines. Food Addit. Contam. 2001, 18, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, N.; Marın, S.; Sanchis, V.; Ramos, A.J. Influence of wateractivity and temperature on growth of isolates of Aspergillus section Nigri obtained from grapes. Int. J. Food Mictobiol. 2004, 96, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, S.; Weiskirchen, R. Resveratrol: How much wine do you have to drink to stay healthy? Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunmei, J.; Junling, S.; Qian, H.; Yanlin, L. Occurrence of toxin-producing fungi in intact and rotten table and wine grapes and related influencing factors. Food Control 2013, 31, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, S.; Ramos, A.J.; Cano-Sancho, G.; Sanchis, V. Mycotoxins: Occurrence, toxicology, and exposure assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 60, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. 2018. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Full_Report_High_Res.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Wiebe, K.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Sands, R.; Tabeau, A.; van der Mensbrugghe, D.; Biewald, A.; Bodirsky, B.; Islam, S.; Kavallari, A.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; et al. Climate change impacts on agriculture in 2050 under a range of plausible socioeconomic and emissions scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 085010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehl, G.A.; Stocker, T.F.; Collins, W.D.; Friedlingstein, P.; Gaye, T.; Gregory, J.M.; Zhao, Z.C. Global climate projections. In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis; Solomon, D.S., Qin, M., Manning, Z., Chen, M., Marquis, K.B., Averyt, M., Tignor, H.L., Miller, Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 747–845. [Google Scholar]

- Soleas, G.J.; Yan, J.; Goldberg, D.M. Assay of ochratoxin A in wine and beer by high pressure liquid chromatography photodiode array and gas chromatography mass selective detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2733–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrenk, D.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L.; Leblanc, J.C.; Nebbia, C.S.; Nielsen, E.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the risk assessment of ochratoxin A in food. EFSA J. 2020, 18, 6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, W.P.P.; Mohd-Redzwan, S. Mycotoxin: Its impact on gut health and microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Apaliya, M.T.; Mahunu, G.K.; Chen, L.; Li, W. Control of ochratoxin A-producing fungi in grape berry by microbial antagonists: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarić, M.Š.; Rašić, D.; Peraica, M. Deleterious effects of mycotoxin combinations involving ochratoxin A. Toxins 2013, 5, 1965–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otteneder, H.; Majerus, P. Occurrence of ochratoxin A (OTA) in wines: Influence of the type of wine and its geographical origin. Food Addit. Contam. 2000, 17, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilani, P.; Silva, A. Controlling ochratoxin A in the vineyard and winery. In Managing Wine Quality; Reynolds, A.G., Ed.; Vitculture and Wine Quality; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 515–546. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.; Harding, J.; Vouillamoz, J. Wine Grape. A Complete Guide to 1368 Vine Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours; Ecco/Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 498–499. [Google Scholar]

- Anli, R.E.; Vural, N.; Bayram, M. Removal of ochratoxin A (OTA) from naturally contaminated wines during the vinification process. J. Inst. Brew. 2011, 117, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachery, B.; Hernandes, K.C.; Veras, F.F.; Schmidt, L.; Augusti, P.R.; Manfroi, V.; Zini, C.A.; Welke, J.E. Effect of Aspergillus carbonarius on ochratoxin A levels, volatile profile and antioxidant activity of the grapes and respective wines. Food Res. Int. 2019, 126, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayman, P.; Baker, J.L. Ochratoxins: A global perspective. Mycopathologia 2006, 162, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, F.F.; Dachery, B.; Manfroi, V.; Welke, J.E. Colonization of Aspergillus carbonarius and accumulation of ochratoxin A in Vitis vinifera, Vitis labrusca, and hybrid grapes–research on the most promising alternatives for organic viticulture. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 101, 2414–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Shi, J.; Zhu, C. Fruit spoilage and ochratoxin a production by Aspergillus carbonarius in the berries of different grape cultivars. Food Control 2013, 30, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, L.; Braga, P.A.; Furtado, M.M.; Delafiori, J.; Dias-Audibert, F.L.; Pereira, G.E.; Reyes, F.G.; Catharino, R.R.; Sant’Ana, A.S. From grape to wine: Fate of ochratoxin A during red, rose, and white winemaking process and the presence of ochratoxin derivatives in the final products. Food Control 2020, 113, 107167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.D.; Ryu, D. Practical strategies to reduce ochratoxin A in foods. Toxins 2024, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, R.; Mattivi, F.; De Rosso, M.; Arapitsas, P.; Bavaresco, L. Advanced knowledge of three important classes of grape phenolics: Anthocyanins, stilbenes and flavonols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 19651–19669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.L.; Hocking, A.D.; Pitt, J.I. Occurrence of fruit rot fungi (Aspergillus section Nigri) on some drying varieties of irrigated grapes. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2004, 10, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, A.; Abarea, M.L.; Bragnlat, M.R.; Cabanes, F.J. Effects of temperature and incubation time on production of ochratoxin A by blace Aspergilli. Res. Microbiol. 2004, 155, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; Parra, R.; Aldred, D.; Magan, N. Water and temperature relation of growth and ochratoxin A production by Aspergillus carbonarius strains from grapes in Europe and Israel. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 97, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouvel, P.; Bonvarlet, L.; Martinez, A.; Lagouarde, P.; Dieng, I.; Martin, P. Wine contamination by ochratoxin A in relation to vine environment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 123, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassemeyer, H.-H. Fungi of grapes. In Biology of Microorganisms on Grapes, in Must and in Wine; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ioriatti, C.; Anfora, G.; Bagnoli, B.; Benelli, G.; Lucchi, A. A review of history and geographical distribution of grapevine moths in Italian vineyards in light of climate change: Looking backward to face the future. Crop Prot. 2023, 173, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, W.; Petrie, P.R.; Bonada, M. Effects of vineyard management practices on winegrape yield components. A review using meta-analysis. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2024, 75, 0750007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, D.A.; Lerno, L.A.; Hjelmeland, A.K.; Ebeler, S.E.; Heymann, H.; Hopfer, H.; Block, K.L.; Brenneman, C.A.; Oberholster, A. Impact of mechanical harvesting and optical berry sorting on grape and wine composition. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 67, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R.; Kamarozaman, N.S.; Ab Dullah, S.S.; Aziz, M.Y.; Aziza, B.A. Health risks evaluation of mycotoxins in plant-based supplements marketed in Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analyte | Matrix | LOD (μg/L) | LOQ (μg/L) | Recovery Range (%) | RSDr (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ochratoxin A | Wine | 0.03 | 0.01 | 85–94 | 2.5–3.5 |

| Variety | Total Samples | Positive Samples | Positive Samples (%) | Positive Samples > 2 μg/L | Min | Max | Median | Average | STDV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syrah | 12 | 5 | 41 | 0 | 0.171 | 1.857 | 0.591 | 0.804 | 0.656 |

| Xinomavro | 23 | 7 | 30 | 1 | 0.288 | 2.078 | 0.652 | 0.930 | 0.591 |

| Sauvignon blanc | 12 | 10 | 83 | 5 | 0.149 | 7.587 | 1.188 | 2.160 | 2.427 |

| Assyrtiko | 25 | 18 | 72 | 2 | 0.160 | 2.523 | 0.601 | 0.744 | 0.639 |

| Variety | Correlation | OTA Concentration vs. Mean Temp | OTA Concentration vs. Max Temp | OTA Concentration vs. Min Temp | OTA Concentration vs. Rain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syrah | R | 0.663 | 0.776 | 0.499 | 0.251 |

| R squared | 0.440 | 0.603 | 0.249 | 0.063 | |

| p value | 0.070 | 0.0007 | 0.058 | 0.366 | |

| Xinomavro | R | 0.860 | 0.648 | 0.832 | −0.432 |

| R squared | 0.739 | 0.430 | 0.6937 | 0.187 | |

| p value | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.050 | |

| Sauvignon blanc | R | 0.639 | 0.449 | 0.7080 | 0.043 |

| R squared | 0.409 | 0.201 | 0.501 | 0.001 | |

| p value | 0.0001 | 0.012 | 0.0001 | 0.821 | |

| Assyrtiko | R | 0.488 | −0.050 | 0.501 | 0.126 |

| R squared | 0.234 | 0.002 | 0.251 | 0.016 | |

| p value | 0.0002 | 0.718 | 0.0001 | 0.361 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miliordos, D.E.; Roussi, L.; Kallithraka, S.; Panagou, E.Z.; Natskoulis, P.I. Impact of Climate Change on the Presence of Ochratoxin A in Red and White Greek Commercial Wines. Foods 2025, 14, 4157. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234157

Miliordos DE, Roussi L, Kallithraka S, Panagou EZ, Natskoulis PI. Impact of Climate Change on the Presence of Ochratoxin A in Red and White Greek Commercial Wines. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4157. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234157

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiliordos, Dimitrios Evangelos, Lamprini Roussi, Stamatina Kallithraka, Efstathios Z. Panagou, and Pantelis I. Natskoulis. 2025. "Impact of Climate Change on the Presence of Ochratoxin A in Red and White Greek Commercial Wines" Foods 14, no. 23: 4157. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234157

APA StyleMiliordos, D. E., Roussi, L., Kallithraka, S., Panagou, E. Z., & Natskoulis, P. I. (2025). Impact of Climate Change on the Presence of Ochratoxin A in Red and White Greek Commercial Wines. Foods, 14(23), 4157. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234157