Functional and Nutritional Properties of Lion’s Mane Mushrooms in Oat-Based Desserts for Dysphagia and Healthy Ageing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of Lion’s Mane Mushroom Powder (LMP)

2.2. Methods for Analysis of LMP

2.2.1. Chemical Composition, Mineral Content, and Amino Acid Analysis

2.2.2. Physical Properties

2.2.3. Bioactive Compounds

2.2.4. Analysis by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3. Preparation of the Dessert Samples

2.4. Analysis of the Dessert Samples

2.4.1. Determination of Dry Matter, Colour, and pH of the Dessert Samples

2.4.2. Measurement of Syneresis

2.4.3. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA)

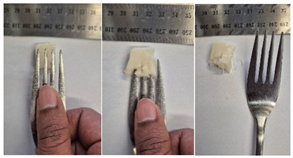

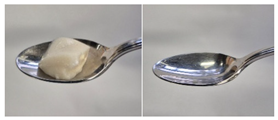

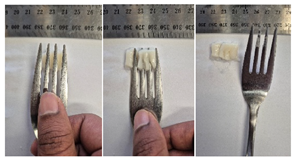

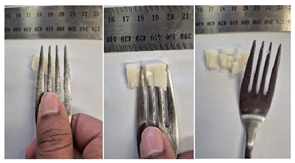

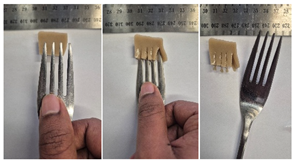

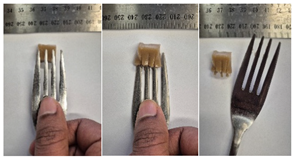

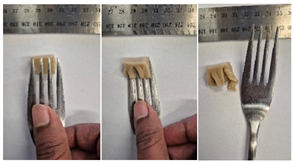

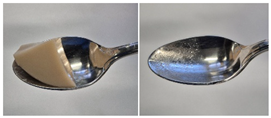

2.4.4. Assessing Dysphagia-Appropriateness of Formulated Desserts

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of LMP

3.1.1. Proximate Analysis

3.1.2. Amino Acid Analysis

3.2. Physical Properties of LMP

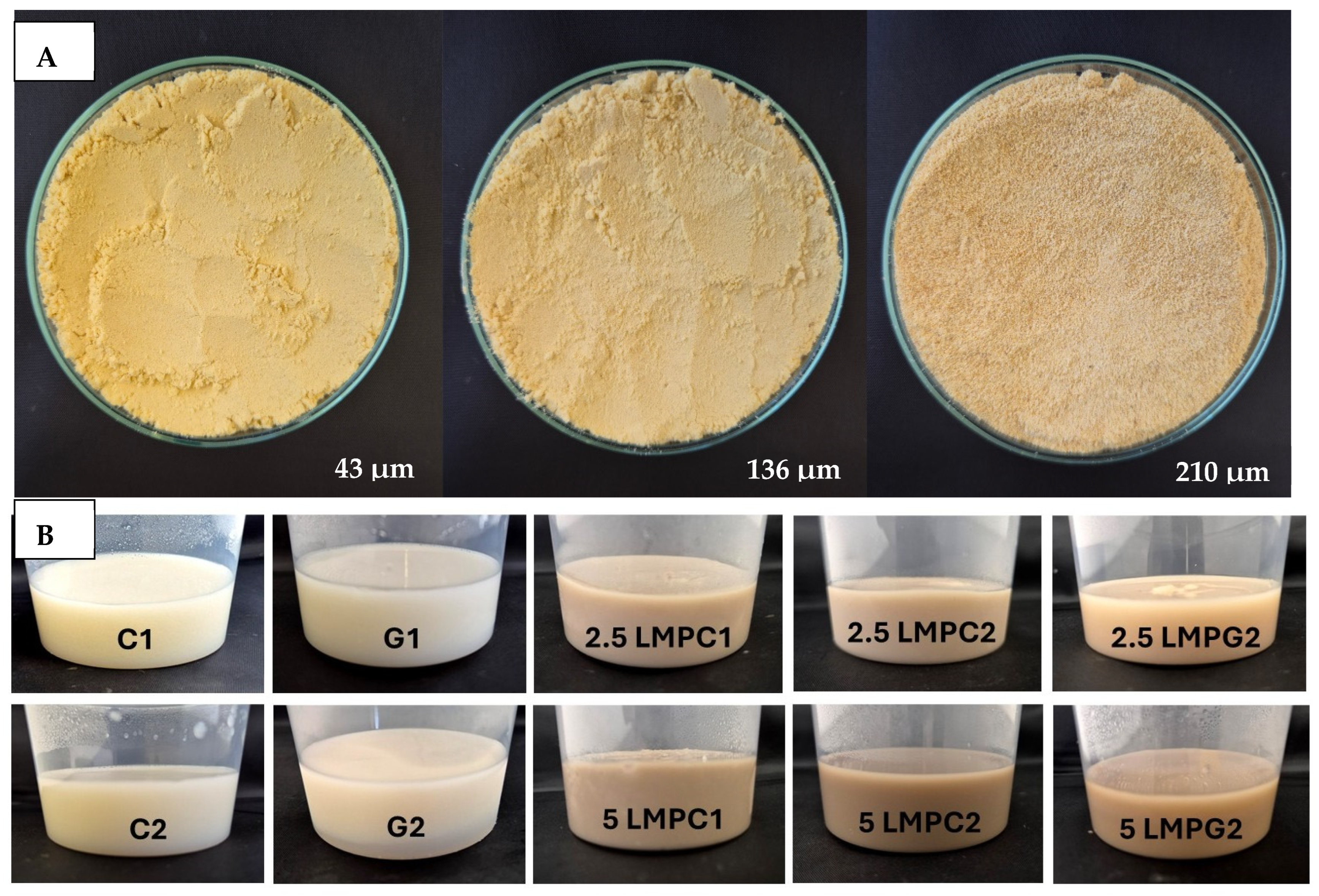

3.2.1. Colour

3.2.2. Bulk Density

3.2.3. pH

3.2.4. Water Solubility, Water Absorption, and Oil Absorption Capacity

3.3. Bioactive Compounds

3.3.1. Vitamin D2 (Ergocalciferol) Content

3.3.2. TPC

3.3.3. Antioxidant Assays

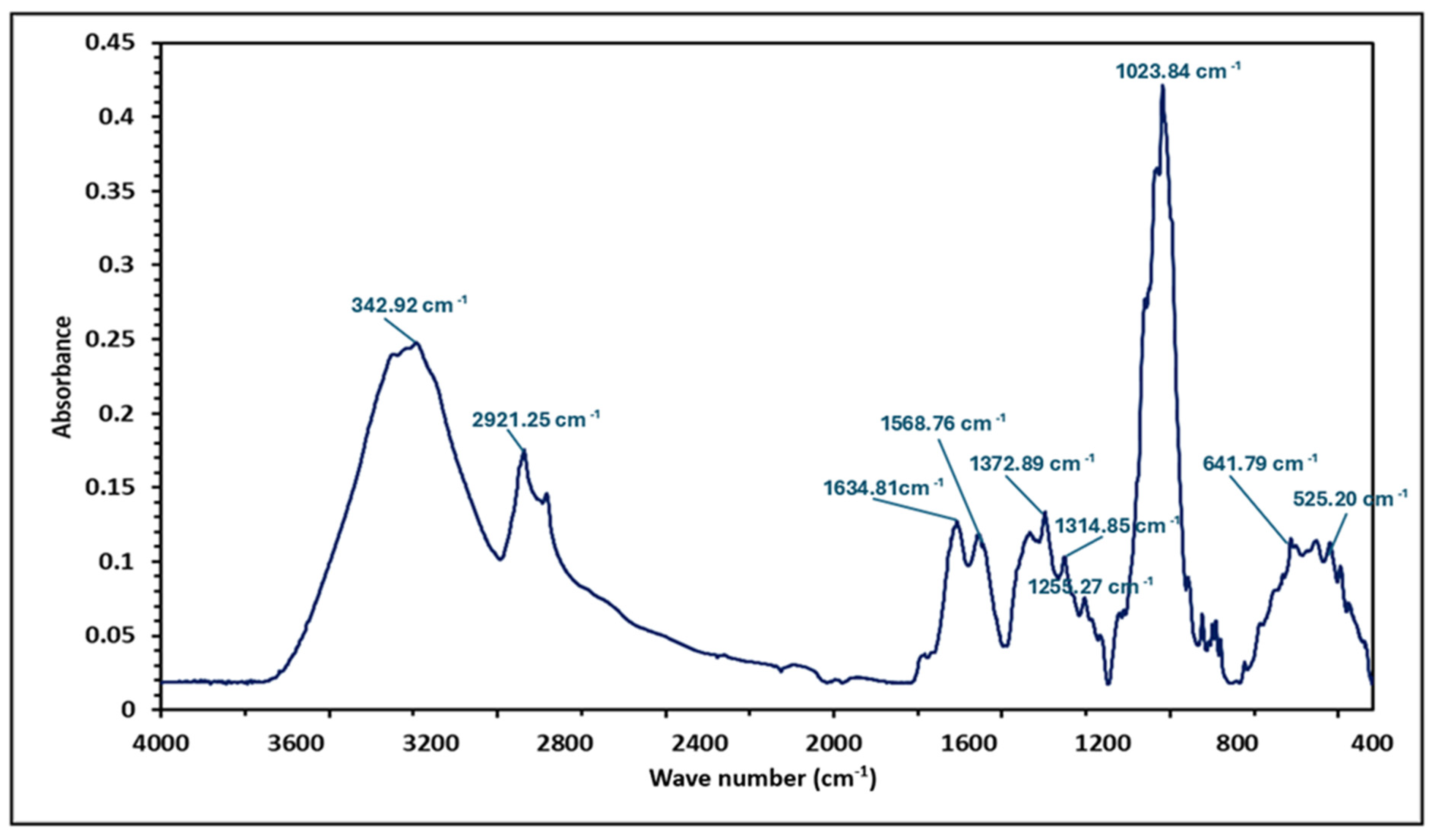

3.4. FTIR

3.5. Visual Properties of the Dessert Samples

3.6. Analysis of the Prepared Dessert Samples

3.6.1. Dry Matter

3.6.2. pH

3.6.3. Colour

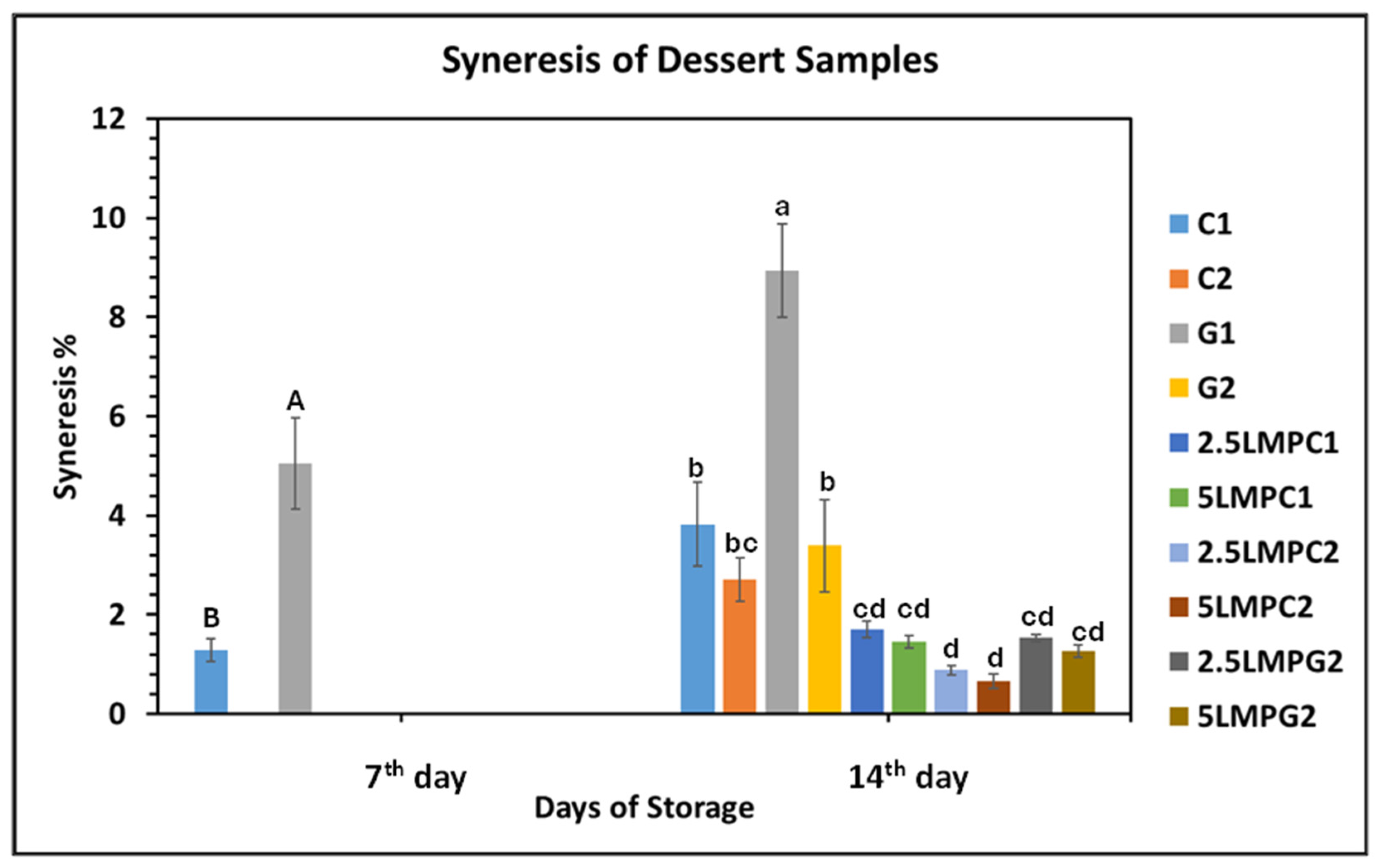

3.6.4. Syneresis

3.6.5. Texture Profile Analysis

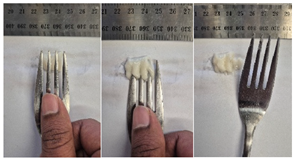

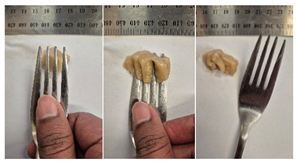

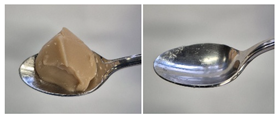

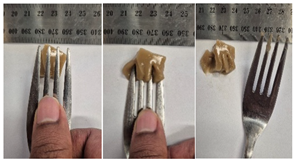

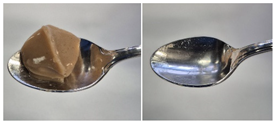

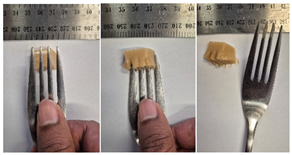

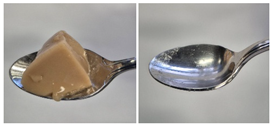

3.6.6. Dysphasia Appropriateness Test

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, A.; Baek, Y.; Lee, H.G. Impact of encapsulation position in pickering emulsions on color stability and intensity turmeric oleoresin. Foods 2025, 14, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Nandi, S.; Banerjee, A.; Sarkar, S.; Chakraborty, N.; Acharya, K. Prospecting medicinal properties of Lion’s Mane mushroom. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydłowska-Tutaj, M.; Szymanowska, U.; Tutaj, K.; Domagała, D.; Złotek, U. The addition of Reishi and Lion’s Mane mushroom powder to pasta influences the content of bioactive compounds and the antioxidant, potential anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties of pasta. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docherty, S.; Doughty, F.L.; Smith, E.F. The Acute and Chronic Effects of Lion’s Mane Mushroom Supplementation on Cognitive Function, Stress and Mood in Young Adults: A Double-Blind, Parallel Groups, Pilot Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Chemistry, nutrition, and health-promoting properties of Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane) mushroom fruiting bodies and mycelia and their bioactive compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7108–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.Y.; Ozgen, S.; Rani, S. Emerging role of edible mushrooms in food industry and its nutritional and medicinal consequences. Eurasian J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 4, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ulziijargal, E.; Yang, J.-H.; Lin, L.-Y.; Chen, C.-P.; Mau, J.-L. Quality of bread supplemented with mushroom mycelia. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lo, Y.M.; Moon, B. Feasibility of using Hericium erinaceus as the substrate for vinegar fermentation. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woraharn, S.; Lailerd, N.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Wangcharoen, W.; Sirisattha, S.; Peerajan, S.; Chaiyasut, C. Evaluation of factors that influence the L-glutamic and γ-aminobutyric acid production during Hericium erinaceus fermentation by lactic acid bacteria. CyTA-J. Food 2016, 14, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Pillidge, C.; Harrison, B.; Adhikari, B. Formulation and characterisation of protein-rich custard-like soft food intended for the elderly with swallowing difficulties. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.-N.; Ho, W.-C.; Wang, L.-H.; Chang, F.-C.; Nhu, N.T.; Chou, L.-W. Prevalence and methods for assessment of oropharyngeal dysphagia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, K.J.; Chu, H.; Chen, R.; Kang, X.L.; Jen, H.-J.; Liu, D.; Shen Hsiao, S.-T.; Chou, K.-R. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia and risk of pneumonia, malnutrition, and mortality in adults aged 60 Years and older: A meta-analysis. Gerontology 2022, 68, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiszman, S.; Laguna, L. Food design for safer swallowing: Focusing on texture-modified diets and sensory stimulation of swallowing via transient receptor potential activation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 50, 101000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Amino acids: Metabolism, functions, and nutrition. Amino Acids 2009, 37, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhapur, R.; Jayakumar, D.; McClements, D. Development and characterization of hybrid meat analogs from whey protein-mushroom composite hydrogels. Gels 2024, 10, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascrizzi, G.I.; Martini, D.; Piazza, L. Nutritional quality of dysphagia-oriented products sold on the Italian market. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1425878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACC. Approved Methods of American Association of Cereal Chemists, 10th ed.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- John, S.; Gunathilake, S.; Aluthge, S.; Farahnaky, A.; Majzoobi, M. Unlocking the potential of chia microgreen: Physicochemical properties, nutritional profile and its application in noodle production. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 5605–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, D.J. Amino acid scoring patterns for protein quality assessment. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S31–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña, M.; Turchiuli, C.; Eim, V.; Rosselló, C.; Simal, S. Stabilization of oil-in-water emulsions with a mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) by-product. J. Food Eng. 2021, 307, 110667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Liu, S.X. Evaluation of amaranth flour processing for noodle making. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Huang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X.; Yue, S.; Yang, W.; Chen, F.; Chang, X.; Chen, L. The effect of superfine grinding on physicochemical properties of three kinds of mushroom powder. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 3528–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzoobi, M.; Ghiasi, F.; Farahnaky, A. Physicochemical assessment of fresh chilled dairy dessert supplemented with wheat germ. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichero, J.A.Y.; Lam, P.; Steele, C.M.; Hanson, B.; Chen, J.; Dantas, R.O.; Duivestein, J.; Kayashita, J.; Lecko, C.; Murray, J.; et al. Development of international terminology and definitions for texture-modified foods and thickened fluids used in dysphagia management: The IDDSI framework. Dysphagia 2017, 32, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pematilleke, N.; Kaur, M.; Adhikari, B.; Torley, P.J. Instrumental method for International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative’s (IDDSI) standard fork pressure test. J. Food Eng. 2022, 326, 111040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.M.F.; Freitas, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; Vasconcelos, M.W.; Roriz, M.; Rodríguez-Alcalá, L.M.; Gomes, A.M.P.; Duarte, A.C. Chemical composition and nutritive value of Pleurotus citrinopileatus var cornucopiae, P. eryngii, P. salmoneo stramineus, Pholiota nameko and Hericium erinaceus. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6927–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulou, M.; Kolonas, A.; Mourtakos, S.; Androutsos, O.; Gortzi, O. Nutritional composition and biological properties of sixteen edible mushroom species. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J. Effects of Hericium erinaceus powder on the digestion, gelatinization of starch, and quality characteristics of Chinese noodles. Cereal Chem. 2021, 98, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D.; Li, W.; Chen, W.; Yang, Y. The prospect of mushroom as an alterative protein: From acquisition routes to nutritional quality, biological activity, application and beyond. Food Chem. 2025, 469, 142600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritota, M.; Manzi, P. Edible mushrooms: Functional foods or functional ingredients? A focus on Pleurotus spp. AIMS Agric. Food 2023, 8, 391–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitayezu, E.; Kang, Y.-H. Effect of particle size on the physicochemical and morphological properties of Hypsizygus marmoreus mushroom powder and its hot-water extracts. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2021, 28, 504–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysakowska, P.; Sobota, A.; Wirkijowska, A. Medicinal mushrooms: Their bioactive components, nutritional value and application in functional food production—A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonkhom, D.; Luangharn, T.; Stadler, M.; Thongklang, N. Cultivation and nutrient compositions of medicinal mushroom, Hericium erinaceus in Thailand. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2024, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.-H.; Naidu, M.; David, R.P.; Bakar, R.; Sabaratnam, V. Neuroregenerative potential of Lion’s Mane mushroom, Hericium erinaceus (Bull.: Fr.) Pers. (Higher Basidiomycetes), in the treatment of peripheral nerve injury (Review). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2012, 14, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhanna, M.; Lund, I.; Bromberg, M.; Wicks, P.; Benatar, M.; Barnes, B.; Pierce, K.; Ratner, D.; Brown, A.; Bertorini, T.; et al. ALSUntangled #73: Lion’s mane. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2024, 25, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yin, Y.-L.; Li, D.; Woo Kim, S.; Wu, G. Amino acids and immune function. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F. Structure, metabolism and functions of amino acids: An overview. In Nutritional and Physiological Functions of Amino Acids in Pigs; Blachier, F., Wu, G., Yin, Y., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.S.; Miles, A.; Braakhuis, A. Nutritional intake and meal composition of patients consuming texture modified diets and thickened fluids: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare 2020, 8, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meybodi, N.M.; Mirmoghtadaie, L.; Sheidaei, Z.; Mortazavian, A.M. Wheat bread: Potential approach to fortify its lysine content. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 15, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Enazi, M.; El-Bahrawy, A.; El-Khateeb, M. In vivo evaluation of the proteins in the cultivated mushrooms. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2012, 2, 1000176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, V.; Alvarez, A. Compositional and nutritional studies on two wild edible mushrooms from northwest Spain. Food Chem. 2001, 75, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreman, L.; Nommensen, P.; Pennings, B.; Laus, M.C. Comprehensive overview of the quality of plant and animal-sourced proteins based on the digestible indispensable amino acid score. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5379–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzler, S.R.; Lieblein-Boff, J.C.; Weiler, M.; Allgeier, C. Plant proteins: Assessing their nutritional quality and effects on health and physical function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Mayookha, V.P.; Geetha, V.; Chetana, R.; Suresh Kumar, G. Influence of different drying techniques on quality parameters of mushroom and its utilization in development of ready to cook food formulation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1342–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Deka, G.; Dutta, H. Effect of particle size, probe type, position and glassware geometry on laboratory-scale ultrasonic extraction of Citrus maxima flavedo. Food Phys. 2025, 2, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Peña, M.A.; Ortega-Regules, A.E.; Anaya de Parrodi, C.; Lozada-Ramírez, J.D. Chemistry, occurrence, properties, applications, and encapsulation of carotenoids—A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, X.; Fang, J.; Chang, Y.; Ning, N.; Guo, H.; Huang, L.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Z. Structures, biological activities, and industrial applications of the polysaccharides from Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane) mushroom: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 97, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, P.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. Food powders flowability characterization: Theory, methods, and applications. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, P.; Viau, M.; Tammel, K.; Innings, F.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Ahrné, L. Effect of powder densities, particle size and shape on mixture quality of binary food powder mixtures. Powder Technol. 2015, 272, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonkhom, D.; Luangharn, T.; Hyde, K.D.; Stadler, M.; Thongklang, N. Optimal conditions for mycelial growth of medicinal mushrooms belonging to the genus Hericium. Mycol. Prog. 2022, 21, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, V.L.; Kawano, D.F.; Silva, D.B.D.A.; Carvalho, I. Carrageenans: Biological properties, chemical modifications and structural analysis—A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Vida, M.; Ramos, A.C.; Lidon, F.J.; Reboredo, F.H.; Gonçalves, E.M. Storage temperature effect on quality and shelf-life of Hericium erinaceus mushroom. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikeman, C.L.; Fahey, G.C. Viscosity as related to dietary fiber: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 46, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishara, J.R.M.; Sila, D.N.; Kenji, G.M.; Buzera, A.K. Nutritional and functional properties of mushroom (Agaricus bisporus & Pleurotus ostreatus) and their blends with maize flour. Am. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 6, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joradon, P.; Rungsardthong, V.; Ruktanonchai, U.; Suttisintong, K.; Iempridee, T.; Thumthanaruk, B.; Vatanyoopaisarn, S.; Sumonsiri, N.; Uttapap, D. Ergosterol content and antioxidant activity of Lion’s Mane mushroom (Hericium erinaceus) and its induction to vitamin D2 by UVC-irradiation. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Agricultural and Biological Sciences, Shenzhen, China, 8–11 August 2022; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardwell, G.; Bornman, J.F.; James, A.P.; Black, L.J. A review of mushrooms as a potential source of dietary vitamin D. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushairi, N.; Phan, C.W.; Sabaratnam, V.; David, P.; Naidu, M. Lion’s Mane mushroom, Hericium erinaceus (Bull.: Fr.) Pers. suppresses H2O2-Induced oxidative damage and LPS-Induced inflammation in HT22 Hippocampal neurons and BV2 microglia. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gąsecka, M.; Mleczek, M.; Siwulski, M.; Niedzielski, P.; Kozak, L. Phenolic and flavonoid content in Hericium erinaceus, Ganoderma lucidum, and Agrocybe aegerita under selenium addition. Acta Aliment. 2016, 45, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Gao, H.; Yin, C.-M.; Shi, D.-F.; Lu, Q.; Fan, X.-Z. Evaluation of in vitro antioxidant and antihyperglycemic activities of extracts from the Lion’s Mane medicinal mushroom, Hericium erinaceus (Agaricomycetes). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2021, 23, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolskaitė, L.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Talou, T. Comprehensive evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of different mushroom species. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Song, D.; Zhao, D.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ou, J.; Sun, S. A study of the mushrooms of boletes by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (G. von Bally & Q. Luo (eds.)). In Proceedings of the Volume 6026, ICO20: Biomedical Optics, Changchun, China, 2 February 2006; p. 60260I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henden, Y.; Gümüş, T.; Kamer, D.D.A.; Kaynarca, G.B.; Yücel, E. Optimizing vegan frozen dessert: The impact of xanthan gum and oat-based milk substitute on rheological and sensory properties of frozen dessert. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, R.R.; Cornish, M.L.; Neish, I.C. Applications of carrageenan: With special reference to iota and kappa forms as derived from the Eucheumatoid seaweeds. In Tropical Seaweed Farming Trends, Problems and Opportunities; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-T.V.; Tsai, J.-S.; Liao, H.-H.; Sung, W.-C. Effect of hydrocolloids on penetration tests, sensory evaluation, and syneresis of milk pudding. Polymers 2025, 17, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDDSI. International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative: Complete IDDSI Framework Detailed Definitions. Available online: https://iddsi.org/framework (accessed on 20 October 2025).

| Sample Name | Gelling Agent (% w/w) | LMP (% w/w) |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | IC * 1% | - |

| C2 | IC 2% | - |

| G1 | Gelatin 1% | - |

| G2 | Gelatin 2% | - |

| 2.5LMPC1 | IC 1% | 2.5 |

| 5LMPC1 | IC 1% | 5 |

| 2.5LMPC2 | IC 2% | 2.5 |

| 5LMPC2 | IC 2% | 5 |

| 2.5LMPG2 | Gelatin 2% | 2.5 |

| 5LMPG2 | Gelatin 2% | 5 |

| 5LMP | - | 5 |

| 10LMP | - | 10 |

| Particle Size | 43 μm | 136 μm | 210 μm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ash (%) | 8.02 | 7.96 | 7.95 |

| Moisture (%) | 5.33 | 5.39 | 5.48 |

| Protein (%) | 15.4 | 16.3 | 16.6 |

| Total fibre (%) | 30.10 | 31.53 | 31.88 |

| Ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) (μg/100 g LMP) | <0.5 | 0.6 | <0.5 |

| Essential amino acids (mg/100 g LMP) | |||

| Histidine | 180 | 160 | 170 |

| Isoleucine | 380 | 380 | 380 |

| Leucine | 810 | 810 | 810 |

| Lysine | 800 | 820 | 710 |

| Methionine | 140 | 150 | 150 |

| Phenylalanine | 400 | 390 | 430 |

| Threonine | 620 | 600 | 620 |

| Valine | 530 | 530 | 510 |

| Non-essential amino acids (mg/100 g LMP) | |||

| Alanine | 890 | 910 | 850 |

| Arginine | 670 | 670 | 690 |

| Aspartic Acid | 1200 | 1200 | 1100 |

| Glutamic Acid | 2200 | 2100 | 2000 |

| Glycine | 500 | 500 | 520 |

| Hydroxyproline | 29 | 30 | 31 |

| Proline | 500 | 510 | 530 |

| Serine | 650 | 640 | 670 |

| Taurine | <5 | <5 | <5 |

| Tyrosine | 380 | 370 | 380 |

| Essential Amino Acids | Content (mg/g Protein) | Reference Amino Acids (mg/g Protein) 1 | AAS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histidine | 11.69 | 18 | 64.94 |

| Isoleucine | 24.68 | 31 | 79.60 |

| Leucine | 52.60 | 63 | 83.49 |

| Lysine | 51.95 | 52 | 99.90 |

| Methionine + Cysteine | 9.09 | 25 | 36.36 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 50.65 | 46 | 110.11 |

| Threonine | 40.26 | 27 | 149.11 |

| Valine | 34.42 | 43 | 80.04 |

| Average | 87.94 |

| LMP Particle Size | Colour | Bulk Density (g/mL) | pH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | |||

| 43 μm | 88.57 ± 0.61 a | −1.89 ± 0.07 b | 31.46 ± 0.25 b | 0.13 ± 0.01 c | 5.33 ± 0.01 c |

| 136 μm | 86.48 ± 1.25 b | −2.40 ± 0.19 c | 32.16 ± 0.62 b | 0.16 ± 0.01 b | 5.39 ± 0.01 b |

| 210 μm | 82.14 ± 1.17 c | 0.39 ± 0.20 a | 34.15 ± 0.41 a | 0.29 ± 0.01 a | 5.48 ± 0.01 a |

| Particle Size | Water Solubility % | Water Absorption % | Oil Absorption % | TPC (mg GAE/g) | DPPH (mg TE/g) | ABTS (mg TE/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43 μm | 34.64 ± 0.82 a | 340.01 ± 3.06 a | 250.89 ± 5.29 a | 72.15 ± 3.57 a | 42.27 ± 1.58 a | 23.89 ± 0.58 a |

| 136 μm | 32.52 ± 0.67 b | 275.30 ± 5.81 b | 218.59 ± 4.13 b | 61.71 ± 2.69 b | 41.54 ± 0.36 a | 24.16 ± 0.19 a |

| 210 μm | 22.24 ± 0.38 c | 243.67 ± 4.53 c | 182.63 ± 7.44 c | 58.01 ± 3.43 b | 38.39 ± 1.11 b | 23.30 ± 1.54 a |

| Sample | Dry Matter (%) | pH | Colour | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | |||

| C1 | 20.09 ± 0.96 g | 7.67 ± 0.02 b | 83.04 ± 0.96 a | −1.58 ± 0.13 e | 9.96 ± 0.39 d |

| C2 | 22.62 ± 0.17 de | 7.94 ± 0.09 a | 82.90 ± 0.58 a | −1.62 ± 0.26 e | 9.42 ± 0.57 d |

| G1 | 21.07 ± 0.03 fg | 7.23 ± 0.01 c | 78.66 ± 0.81 b | −3.10 ± 0.03 g | 1.24 ± 0.14 f |

| G2 | 21.73 ± 0.11 ef | 7.07 ± 0.01 d | 77.56 ± 0.44 b | −2.34 ± 0.08 f | 7.89 ± 0.35 e |

| 2.5LMPC1 | 23.38 ± 0.30 cd | 6.16 ± 0.03 f | 54.26 ± 1.66 f | 0.62 ± 0.01 c | 13.29 ± 0.39 b |

| 5LMPC1 | 25.08 ± 0.01 b | 5.67 ± 0.08 h | 42.75 ± 1.45 g | 1.50 ± 0.15 b | 11.67 ± 0.94 c |

| 2.5LMPC2 | 25.28 ± 0.20 b | 6.57 ± 0.03 e | 67.86 ± 1.95 d | 1.46 ± 0.05 b | 16.82 ± 0.58 a |

| 5LMPC2 | 27.29 ± 0.12 a | 6.19 ± 0.03 f | 60.04 ± 0.46 e | 2.37 ± 0.06 a | 16.34 ± 0.39 a |

| 2.5LMPG2 | 23.89 ± 0.19 c | 5.81 ± 0.05 g | 70.50 ± 1.07 c | 0.01 ± 0.04 d | 15.80 ± 0.39 a |

| 5LMPG2 | 25.49 ± 0.59 b | 5.72 ± 0.02 gh | 34.96 ± 1.18 h | 1.30 ± 0.07 b | 10.42 ± 0.48 d |

| Sample | Hardness (g) | Springiness (%) | Cohesiveness | Gumminess (g) | Chewiness (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 28.55 ± 0.18 h | 99.98 ± 0.29 a | 0.61 ± 0.03 c | 17.50 ± 0.80 g | 17.53 ± 0.83 h |

| C2 | 99.54 ± 5.08 c | 99.89 ± 0.22 a | 0.45 ± 0.02 de | 44.20 ± 1.82 d | 44.29 ± 1.85 d |

| G1 | 22.97 ± 0.89 h | 100.14 ± 0.35 a | 0.58 ± 0.01 c | 13.37 ± 0.53 g | 13.39 ± 0.52 h |

| G2 | 104.75 ± 4.00 c | 100.15 ± 0.16 a | 0.49 ± 0.01 d | 51.10 ± 1.65 c | 51.18 ± 1.63 c |

| 2.5LMPC1 | 46.22 ± 4.19 g | 100.40 ± 0.04 a | 0.85 ± 0.03 a | 39.07 ± 3.52 de | 39.23 ± 3.52 de |

| 5LMPC1 | 57.09 ± 3.25 f | 100.16 ± 0.51 a | 0.46 ± 0.04 de | 26.07 ± 1.17 f | 26.11 ± 1.11 g |

| 2.5LMPC2 | 117.78 ± 6.17 b | 100.25 ± 0.24 a | 0.82 ± 0.03 a | 97.04 ± 5.67 a | 97.28 ± 5.62 a |

| 5LMPC2 | 132.08 ± 5.03 a | 100.13 ± 0.33 a | 0.68 ± 0.05 b | 89.78 ± 6.21 b | 89.89 ± 6.16 b |

| 2.5LMPG2 | 70.12 ± 2.86 e | 99.92 ± 0.49 a | 0.45 ± 0.03 de | 31.59 ± 2.82 f | 31.55 ± 2.74 fg |

| 5LMPG2 | 78.82 ± 1.66 d | 100.29 ± 0.49 a | 0.42 ± 0.02 e | 32.80 ± 1.73 ef | 32.89 ± 1.80 ef |

| Sample | Fork Pressure Test | Spoon Tilt Test |

|---|---|---|

| C1 |  |  |

| C2 |  |  |

| G1 |  |  |

| G2 |  |  |

| 2.5LMPC1 |  |  |

| 5LMPC1 |  |  |

| 2.5LMPC2 |  |  |

| 5LMPC2 |  |  |

| 2.5LMPG2 |  |  |

| 5LMPG2 |  |  |

| Sample | Peak Positive Distance (mm) | Positive Area (g.s) | Negative Area (g.s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 5.17 ± 0.55 c | 12585.00 ± 6.10 f | −37.13 ± 9.15 de |

| C2 | 7.94 ± 0.33 ab | 12914.70 ± 64.50 cd | −12.31 ± 3.83 ab |

| G1 | 5.98 ± 0.63 bc | 12578.70 ± 26.80 f | −50.62 ± 3.60 e |

| G2 | 8.70 ± 0.81 a | 12826.00 ± 121.60 cde | −6.91 ± 2.76 a |

| 2.5LMPC1 | 6.40 ± 0.34 bc | 12636.70 ± 10.40 ef | −29.81 ± 2.45 cd |

| 5LMPC1 | 8.96 ± 1.50 a | 12767.30 ± 93.80 def | −35.04 ± 4.65 cd |

| 2.5LMPC2 | 9.46 ± 0.39 a | 13188.70 ± 146.70 b | −24.07 ± 5.31 bcd |

| 5LMPC2 | 10.04 ± 0.89 a | 13569.70 ± 36.10 a | −28.29 ± 1.58 cd |

| 2.5LMPG2 | 8.93 ± 0.60 a | 13034.70 ± 74.30 bc | −20.42 ± 6.36 abc |

| 5LMPG2 | 9.68 ± 0.96 a | 13438.70 ± 58.40 a | −24.68 ± 6.36 bcd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gunathilake, S.; Aluthge, S.; Farahnaky, A.; Huynh, T.; Ssepuuya, G.; Majzoobi, M. Functional and Nutritional Properties of Lion’s Mane Mushrooms in Oat-Based Desserts for Dysphagia and Healthy Ageing. Foods 2025, 14, 4153. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234153

Gunathilake S, Aluthge S, Farahnaky A, Huynh T, Ssepuuya G, Majzoobi M. Functional and Nutritional Properties of Lion’s Mane Mushrooms in Oat-Based Desserts for Dysphagia and Healthy Ageing. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4153. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234153

Chicago/Turabian StyleGunathilake, Samiddhi, Supuni Aluthge, Asgar Farahnaky, Tien Huynh, Geoffrey Ssepuuya, and Mahsa Majzoobi. 2025. "Functional and Nutritional Properties of Lion’s Mane Mushrooms in Oat-Based Desserts for Dysphagia and Healthy Ageing" Foods 14, no. 23: 4153. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234153

APA StyleGunathilake, S., Aluthge, S., Farahnaky, A., Huynh, T., Ssepuuya, G., & Majzoobi, M. (2025). Functional and Nutritional Properties of Lion’s Mane Mushrooms in Oat-Based Desserts for Dysphagia and Healthy Ageing. Foods, 14(23), 4153. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234153