Metabolic Engineering Strategy for Bacillus subtilis Producing MK-7

Abstract

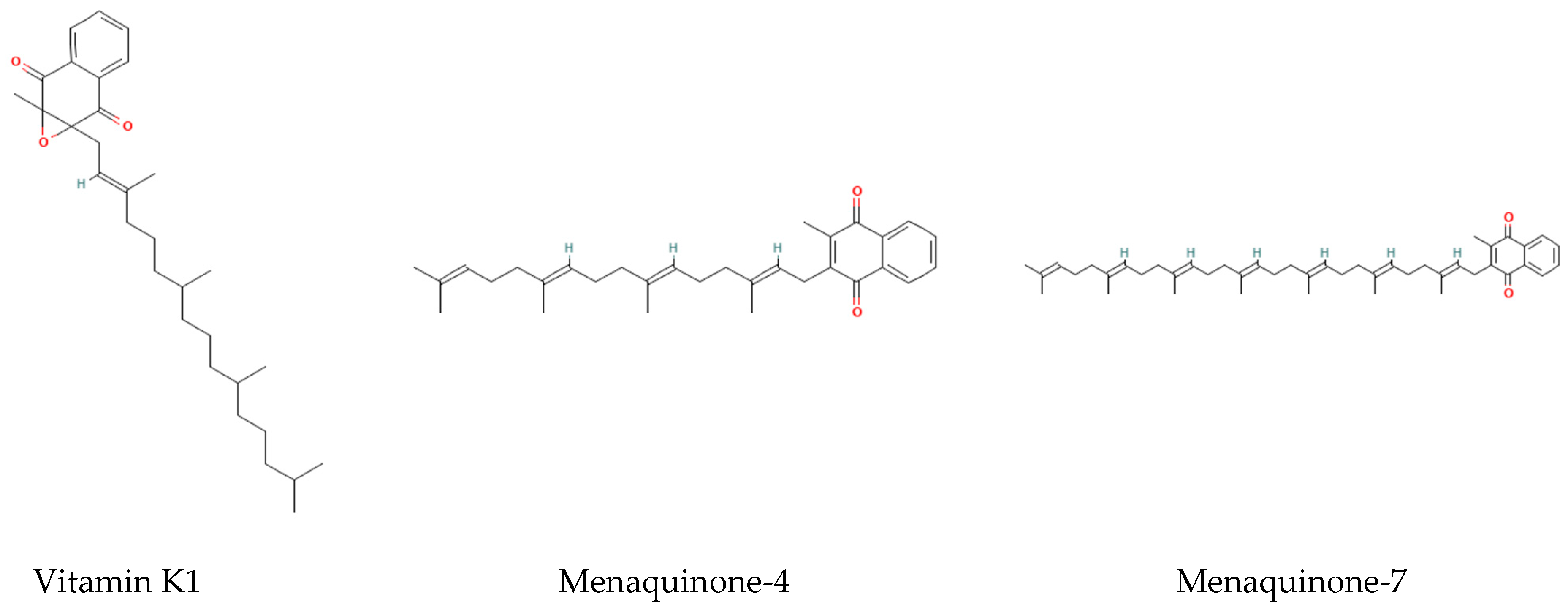

1. Introduction

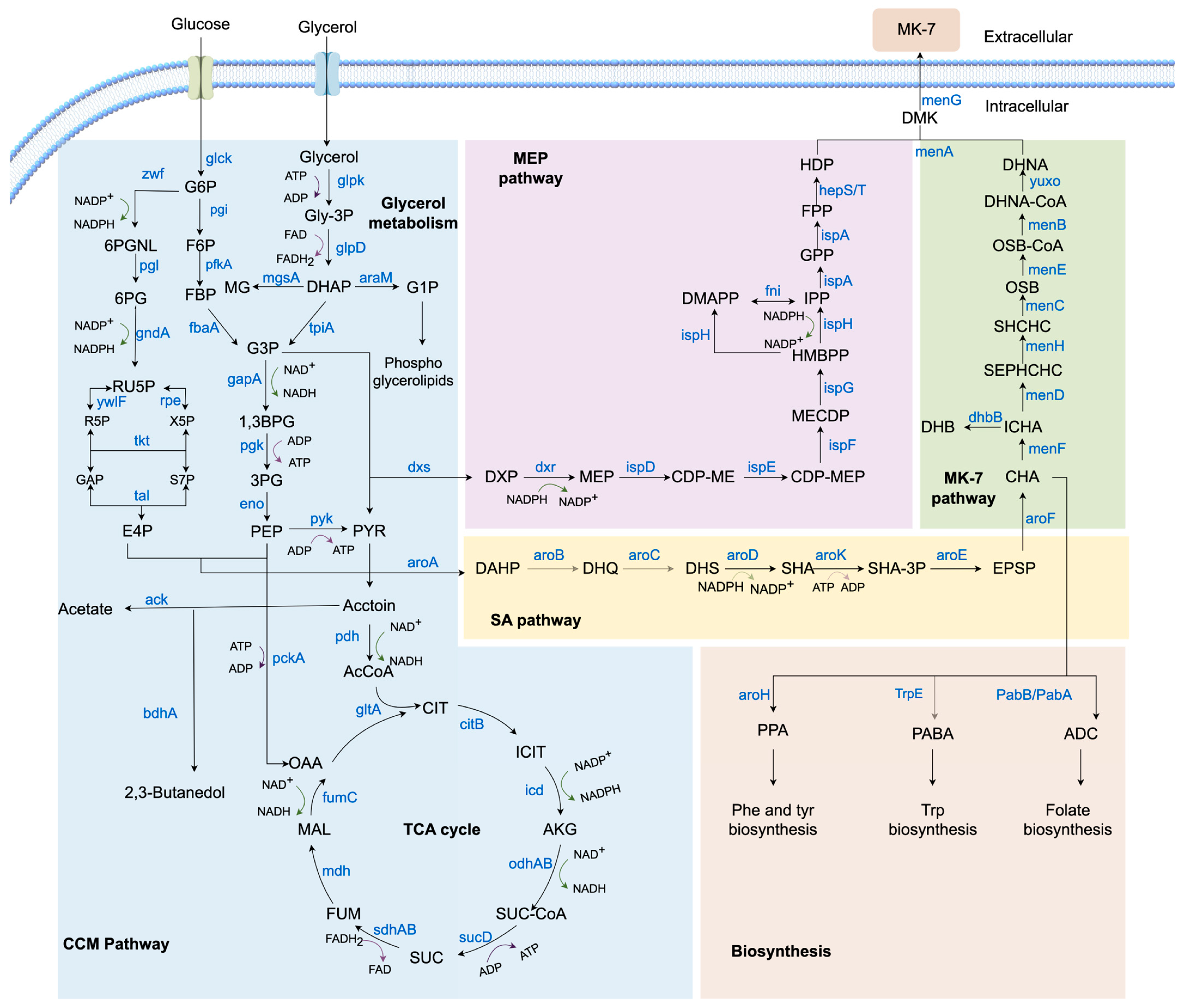

2. Biosynthetic Pathway of MK-7 in Bacillus subtilis

2.1. CCM Pathway

2.1.1. Glycerol Metabolism Pathway

2.1.2. EMP Pathway

2.1.3. PPP Pathway

2.1.4. TCA Cycle

2.2. MEP Pathway

2.3. SA Pathway

2.4. MK-7 Pathway

2.5. Biosynthesis

3. Metabolic Pathway Modification

3.1. Substrate Metabolism Module

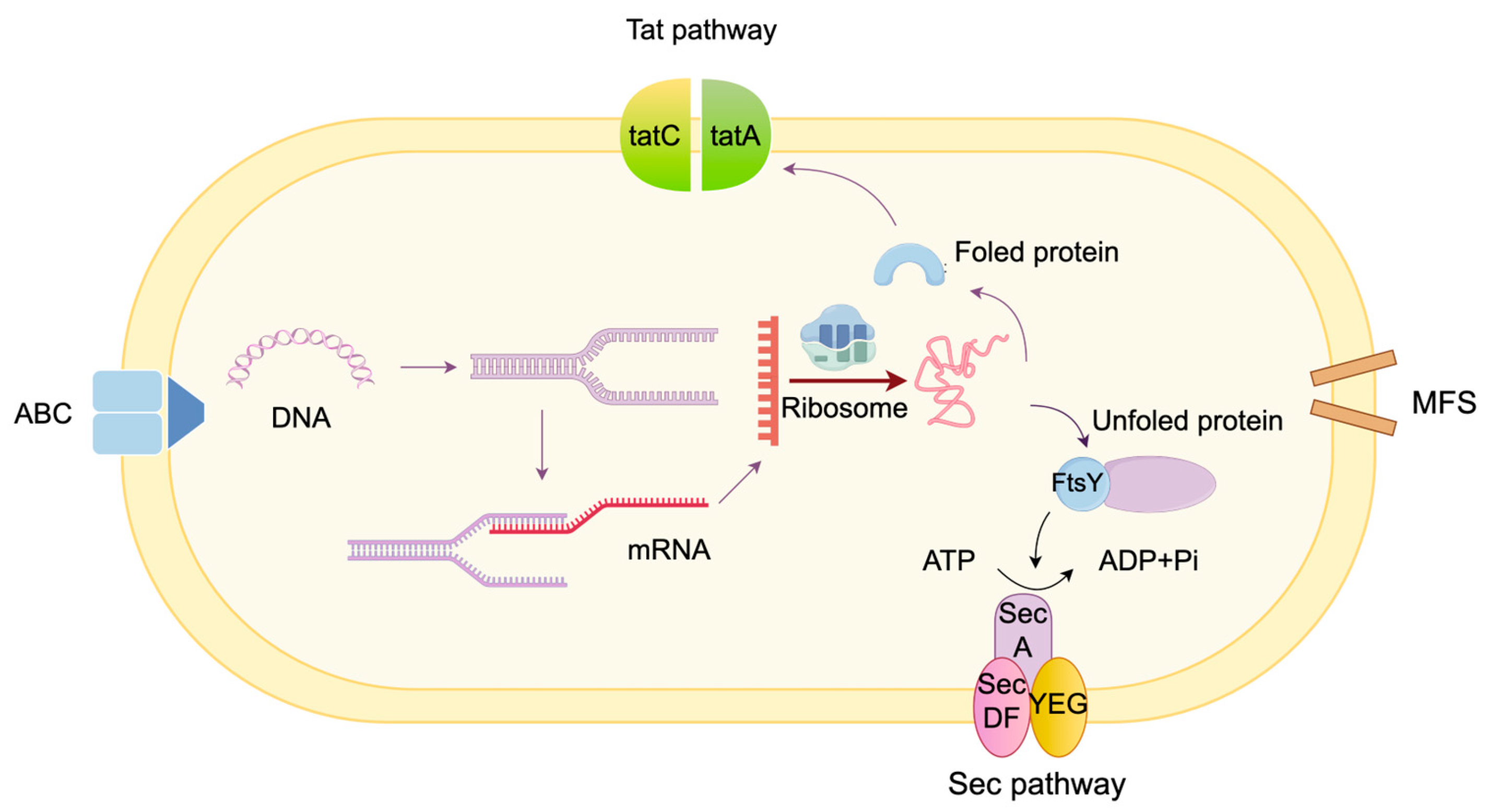

3.2. Secretion Pathway Module

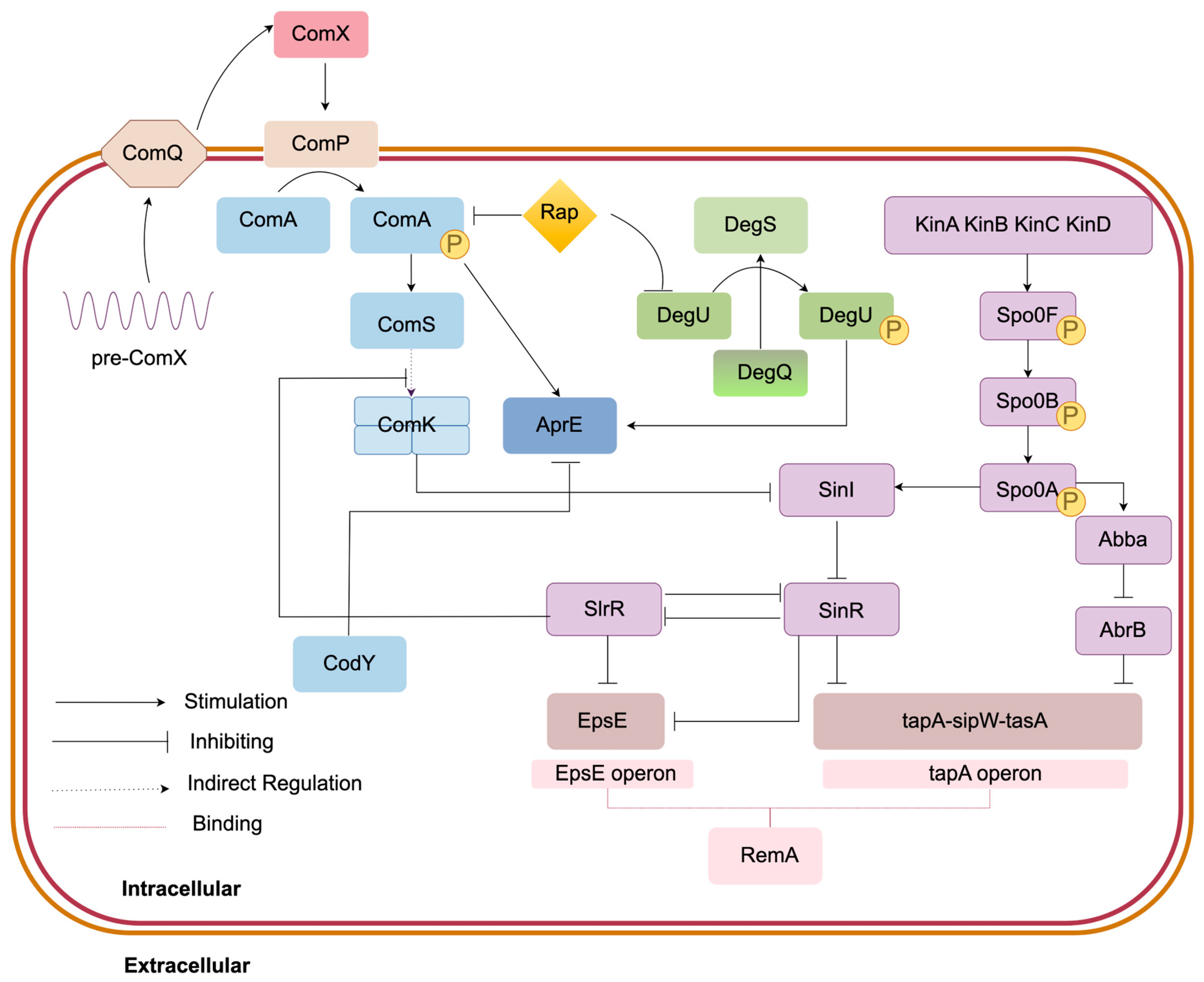

3.3. Spore and Biofilm Formation Module

3.3.1. Spo0A-KinA-E Regulation Mechanism

3.3.2. SinI/SinR Regulatory System

| Target Gene | Method | Strain Background | MK-7 Improvement | MK-7 Titers or Yields | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glpk | PlapS promoter | BSMK | 6% | 58.9 ± 1.0 mg/L | [49] |

| glpD | PlapS promoter | BSMK-1 | 10% | 61.1 ± 0.5 mg/L | [49] |

| mgsA | Deletion | BSMK-2 | 12% | 62.3 ± 0.5 mg/L | [49] |

| araM | Deletion | BSMK-3 | 15% | 70.3 ± 0.8 mg/L | [49] |

| dxs, fni, dxr, menF | P43 promoter | Bacillus subtilis168 | 2.8 | 32.93 mg/L | [50] |

| aroA | Phbs promoter | ||||

| menA | PglgV promoter | ZQ12 | 2.9 | 177.38 mg/L | [52] |

| menD | PcspD promoter | BSW01 | 1.75 | 101.36 mg/L | [52] |

| bdhA | Deletion | Bacillus subtilis 168 | 2 | 30.6 mg/L | [54] |

| ispD | P43 promoter | BS20 | 10% | 353.2 ± 1.2 mg/L | [55] |

| ispF | P43 promoter | BS20D | 3.9% | 332.6 ± 3 mg/L | [55] |

| ispH | P43 promoter | BS20DF | 15.8% | 370.8 ± 5.2 mg/L | [55] |

| ispG | P43 promoter | BS20DFH | 29.3% | 415 ± 3.2 mg/L | [55] |

| spo0A | PabrB promoter | Bacillus subtilis 168 | 40 | 360 mg/L | [67] |

| PspoiiA promoter | |||||

| sinR | Deletion | Bacillus subtilis 168 | 2.6 | 102.56 ± 2.84 mg/L | [70] |

3.3.3. AbA/AbrB Regulation Mechanism

3.3.4. RemA/RemB Regulation Mechanism

3.4. Antioxidant Module

4. Synergistic Effect of Fermentation Process Optimization and Metabolic Engineering Modification

5. Challenges and Prospects

5.1. The Discharge Mechanism Is Not Clear

5.2. Insufficient Supply of Precursors

5.3. Limitations of Metabolic Pathway Modification

5.4. Challenges in Applying Bioinformatics Tools

6. Research Needs

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovács, Á.T. Bacillus subtilis. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 724–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Begum, F.; Rabaan, A.A.; Aljeldah, M.; Al Shammari, B.R.; Alawfi, A.; Alshengeti, A.; Sulaiman, T.; Khan, A. Classification and multifaceted potential of secondary metabolites produced by Bacillus subtilis group: A comprehensive review. Molecules 2023, 28, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, D.L.; Nosal, D.G.; Swetha, R.; Jifang, Z.; Luying, C.; Hershow, R.C.; van Breemen, R.B.; Erik, W.; Hafner, J.W.; Rubinstein, I. Effects of vitamin K1 treatment on plasma concentrations of long-acting anticoagulant rodenticide enantiomers following inhalation of contaminated synthetic cannabinoids. Clin. Toxicol. 2020, 58, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Inaba, N.; Yamashita, T. MK-7 and Its Effects on Bone Quality and Strength. Nutrients 2020, 12, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Schurgers, L.J.; Uenishi, K. Comparison of menaquinone-4 and menaquinone-7 bioavailability in healthy women. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orticello, M.; Cavallaro, R.A.; Antinori, D.; Raia, T.; Lucarelli, M.; Fuso, A. Amyloidogenic and Neuroinflammatory Molecular Pathways Are Contrasted Using Menaquinone 4 (MK4) and Reduced Menaquinone 7 (MK7R) in Association with Increased DNA Methylation in SK-N-BE Neuroblastoma Cell Line. Cells 2024, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rønn, S.H.; Harsløf, T.; Oei, L.; Pedersen, S.B.; Langdahl, B.L. The effect of vitamin MK-7 on bone mineral density and microarchitecture in postmenopausal women with osteopenia, a 3-year randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Osteoporos. Int. 2021, 32, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifzadeh, M.; Mottaghi-Dastjerdi, N.; Soltany-Rezaee-Rad, M.; Shariatpanahi, M.; Khalid AL-Yasari, I.; Noroozi Eshlaghi, S. Optimization of culture condition for the production of menaquinone-7 by Bacillus subtilis Natto. Res. Mol. Med. 2022, 10, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapen, M.H.; Braam, L.A.; Drummen, N.E.; Bekers, O.; Hoeks, A.P.; Vermeer, C. Menaquinone-7 supplementation improves arterial stiffness in healthy postmenopausal women. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 113, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwakenberg, S.R.; de Jong, P.A.; Bartstra, J.W.; van Asperen, R.; Westerink, J.; de Valk, H.; Slart, R.; Luurtsema, G.; Wolterink, J.M.; de Borst, G.J.; et al. The effect of menaquinone-7 supplementation on vascular calcification in patients with diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdinia, E.; Demirci, A.; Berenjian, A. Production and application of menaquinone-7 (vitamin K2): A new perspective. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 33, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smajdor, J.; Jedlińska, K.; Porada, R.; Górska-Ratusznik, A.; Policht, A.; Śróttek, M.; Więcek, G.; Baś, B.; Strus, M. The impact of gut bacteria producing long chain homologs of vitamin K2 on colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, X.; Zuo, S.; Tang, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, H. Metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica to produce menaquinone-7. Process Biochem. 2025, 157, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baj, A.; Wałejko, P.; Kutner, A.; Kaczmarek, Ł.; Morzycki, J.W.; Witkowski, S. Convergent synthesis of menaquinone-7 (MK-7). Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, G.; Yang, W.; Zhong, X.; Liu, J.; Huo, X.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Tao, Y. Highly efficient production of menaquinone-7 from glucose by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 2021, 10, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, J.; Meng, R.; Yu, T.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, P.; Gao, Z. Screening and identification of genes involved in β-alanine biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 743, 109664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaldo, F.; Leroy, F. Review: Bacterially produced vitamin K2 and its potential to generate health benefits in humans. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 147, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guan, N.; Li, J.; Shin, H.-D.; Du, G.; Chen, J. Development of GRAS strains for nutraceutical production using systems and synthetic biology approaches: Advances and prospects. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Niu, P.; Liu, L.; Ye, T.; Ding, W.; Wei, X.; Zhu, T.; Li, Z.; Fang, H.; Liu, H. Multivariate Modular Metabolic Engineering for the Enhanced Biosynthesis of Cytidine in Bacillus subtilis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 12776–12786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Chen, Q.; Luo, J.; Cui, W.; Zhou, Z. Development of a glycerol-inducible expression system for high-yield heterologous protein production in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01322-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, C.; Beijer, L.; Rutberg, B.; Rutberg, L. Glycerol catabolism in Bacillus subtilis: Nucleotide sequence of the genes encoding glycerol kinase (glpK) and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (glpD). Microbiology 1990, 136, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, M.; Liu, L.; Hui, X.; Wang, B.; Ma, K.; Yang, X. Improvement of the catalytic performance of glycerol kinase from Bacillus subtilis by chromosomal site-directed mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2022, 44, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, K.; Chen, Z.; Shen, L.; Gao, X.-D.; Nakanishi, H.; Li, Z. Efficient biosynthesis of rare sugars using glycerol as a sole carbon source in metabolic engineered Bacillus subtilis. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldan, H.; Sterner, R.; Babinger, P. Identification and characterization of a bacterial glycerol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase: Ni2+-dependent AraM from Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 7376–7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldan, H. Nachweis Archaea-typischer Lipide in Bacteria über die Aufklärung der Funktion von AraM und PcrB aus Bacillus subtilis. Ph.D. Thesis, University in Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Shin, H.-D.; Chen, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Combinatorial promoter engineering of glucokinase and phosphoglucoisomerase for improved N-acetylglucosamine production in Bacillus subtilis. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Yan, D.; Miao, L.; Cai, D.; Ma, X.; Chen, S. High Production of Nattokinase via Fed-Batch Fermentation of the γ-PGA-Deficient Strain of Bacillus licheniformis. Fermentation 2023, 9, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blencke, H.-M.; Homuth, G.; Ludwig, H.; Mäder, U.; Hecker, M.; Stülke, J. Transcriptional profiling of gene expression in response to glucose in Bacillus subtilis: Regulation of the central metabolic pathways. Metab. Eng. 2003, 5, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Valladares, N.; Martínez, L.M.; Flores, N.; Hernández-Chávez, G.; Martínez, A.; Bolívar, F.; Gosset, G. Physiologic Consequences of Glucose Transport and Phosphoenolpyruvate Node Modifications in Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 22, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Sun, Y.; Fu, S.; Xia, M.; Su, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, D. Improving the Production of Riboflavin by Introducing a Mutant Ribulose 5-Phosphate 3-Epimerase Gene in Bacillus subtilis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 704650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.M.; Gerwig, J.; Hammer, E.; Herzberg, C.; Commichau, F.M.; Völker, U.; Stülke, J. Physical interactions between tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes in Bacillus subtilis: Evidence for a metabolon. Metab. Eng. 2011, 13, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, W.; Nomura, C.T.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q. Increased flux through the TCA cycle enhances bacitracin production by Bacillus licheniformis DW2. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 6935–6946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tännler, S.; Decasper, S.; Sauer, U. Maintenance metabolism and carbon fluxes in Bacillus species. Microb. Cell Factories 2008, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiffin, R.M.; Sullivan, S.M.; Carlson, G.M.; Holyoak, T. Differential inhibition of cytosolic PEPCK by substrate analogues. Kinetic and structural characterization of inhibitor recognition. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 2099–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, D.; Pu, Z.; Bao, Y. Integration of metabolic pathway manipulation and promoter engineering for the fine-tuned biosynthesis of malic acid in Bacillus coagulans. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 2597–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, N.; Maaheimo, H.; Szyperski, T.; Hohmann, H.-P.; Sauer, U. The phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase also catalyzes C3 carboxylation at the interface of glycolysis and the TCA cycle of Bacillus subtilis. Metab. Eng. 2004, 6, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, J.; Pratzka, I.; Meyer, H.; Albrecht, D.; Lalk, M.; Ehrenreich, A.; Schweder, T. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for growth on overflow metabolites. Microb. Cell Factories 2013, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Xue, D.; Abdallah, I.I.; Dijkshoorn, L.; Setroikromo, R.; Lv, G.; Quax, W.J. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for terpenoid production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 9395–9406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Ahring, B.K. Enhancing isoprene production by genetic modification of the 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway in Bacillus subtilis. Applied and environmental microbiology 2011, 77, 2399–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.-J.; Gao, T.-T.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Sun, D.-M.; Song, F.-P. Transcriptional profile of gene clusters involved in the methylerythritol phosphate pathway in Bacillus subtilis 916. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramastya, H.; Song, Y.; Elfahmi, E.Y.; Sukrasno, S.; Quax, W.J. Positioning Bacillus subtilis as terpenoid cell factory. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 1839–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; He, S.; Abdallah, I.I.; Jopkiewicz, A.; Setroikromo, R.; van Merkerk, R.; Tepper, P.G.; Quax, W.J. Engineering of Multiple Modules to Improve Amorphadiene Production in Bacillus subtilis Using CRISPR-Cas9. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 4785–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBee, D.P.; Hulsey, Z.N.; Hedges, M.R.; Baccile, J.A. Stable Isotopic Labeling of Dimethylallyl Pyrophosphate (DMAPP) Reveals Compartmentalization of Isoprenoid Biosynthesis during Sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 19777–19787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwedt, I.; Schöne, K.; Eckert, M.; Pizzinato, M.; Winkler, L.; Knotkova, B.; Richts, B.; Hau, J.-L.; Steuber, J.; Mireles, R.; et al. The low mutational flexibility of the EPSP synthase in Bacillus subtilis is due to a higher demand for shikimate pathway intermediates. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 3604–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicke, D.; Schulz, L.M.; Lentes, S.; Scholz, P.; Poehlein, A.; Gibhardt, J.; Daniel, R.; Ischebeck, T.; Commichau, F.M. Identification of the first glyphosate transporter by genomic adaptation. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 1287–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Peng, C.; Lu, J.; Hu, X.; Ren, L. Enhancing menaquinone-7 biosynthesis by adaptive evolution of Bacillus natto through chemical modulator. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.A.; Nester, E.W. The regulatory significance of intermediary metabolites: Control of aromatic acid biosynthesis by feedback inhibition in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 1965, 12, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Ajo-Franklin, C.M.; Igoshin, O.A. The growth benefits and toxicity of quinone synthesis are balanced by a dual regulatory mechanism and substrate limitations. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, G.; Song, H. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for high-titer production of menaquinone-7. AIChE J. 2020, 66, e16754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, G.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Wang, P. Bottom-up synthetic biology approach for improving the efficiency of menaquinone-7 synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Microb. Cell Factories 2022, 21, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A.; Chen, M.; Fyfe, P.K.; Guo, Z.; Hunter, W.N. Structure and Reactivity of Bacillus subtilis MenD Catalyzing the First Committed Step in Menaquinone Biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 401, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Li, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lv, J.; Zhu, R.; Pu, C.; Zhao, H.; Fu, G.; Zhang, D. Increasing Vitamin K2 Synthesis in Bacillus subtilis by Controlling the Expression of MenD and Stabilizing MenA. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 22672–22681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harirchi, S.; Sar, T.; Ramezani, M.; Aliyu, H.; Etemadifar, Z.; Nojoumi, S.A.; Yazdian, F.; Awasthi, M.K.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Bacillales: From Taxonomy to Biotechnological and Industrial Perspectives. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Gao, X.; Huang, J.; Luo, Y.; Tao, W.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Study on the effects of bdhA knockout on coproduction of menaquinone-7 and nattokinase by Bacillus subtilis based on RNA-Seq analysis. Process Biochem. 2024, 144, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xia, H.; Cui, S.; Lv, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Combinatorial Methylerythritol Phosphate Pathway Engineering and Process Optimization for Increased Menaquinone-7 Synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Gong, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Production of proteins and commodity chemicals using engineered Bacillus subtilis platform strain. Essays Biochem. 2021, 65, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling Lin, F.; Zi Rong, X.; Wei Fen, L.; Jiang Bing, S.; Ping, L.; Chun Xia, H. Protein secretion pathways in Bacillus subtilis: Implication for optimization of heterologous protein secretion. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fu, G.; Gai, Y.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, D.; Wen, J. Combinatorial Sec pathway analysis for improved heterologous protein secretion in Bacillus subtilis: Identification of bottlenecks by systematic gene overexpression. Microb. Cell Factories 2015, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Guo, L.; Li, L.; Yang, R.; Zhao, W.; Lyu, X. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals the underlying mechanism for over-accumulation of menaquinone-7 in Bacillus subtilis natto mutant. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 174, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, E.; Monterrosa, R.G.; Kovács, Á.T. From environmental signals to regulators: Modulation of biofilm development in Gram-positive bacteria. J. Basic Microbiol. 2014, 54, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špacapan, M.; Danevčič, T.; Štefanic, P.; Porter, M.; Stanley-Wall, N.R.; Mandic-Mulec, I. The ComX quorum sensing peptide of Bacillus subtilis affects biofilm formation negatively and sporulation positively. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spacapan, M.; Danevčič, T.; Mandic-Mulec, I. ComX-Induced Exoproteases Degrade ComX in Bacillus subtilis PS-216. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Put, H.; Gerstmans, H.; Vande Capelle, H.; Fauvart, M.; Michiels, J.; Masschelein, J. Bacillus subtilis as a host for natural product discovery and engineering of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2024, 41, 1113–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Palma, C.S.D.; Chen, Z.; Zarazúa-Osorio, B.; Fujita, M.; Igoshin, O.A. Biophysical modeling reveals the transcriptional regulatory mechanism of Spo0A, the master regulator in starving Bacillus subtilis. mSystems 2025, 10, e0007225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Zhu, S.; Lu, J.; Hu, X.; Ren, L. Transcriptomic analysis of gene expression of menaquinone-7 in Bacillus subtilis natto toward different oxygen supply. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tojo, S.; Hirooka, K.; Fujita, Y. Expression of kinA and kinB of Bacillus subtilis, necessary for sporulation initiation, is under positive stringent transcription control. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 1656–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Lv, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Liu, L. Engineering a bifunctional Phr60-Rap60-Spo0A quorum-sensing molecular switch for dynamic fine-tuning of menaquinone-7 synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 1826–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.A.; Rodrigues, C.; Lewis, R.J. Molecular Basis of the Activity of SinR Protein, the Master Regulator of Biofilm Formation in Bacillus subtilis*♦. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 10766–10778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yang, N.; Zheng, S.; Yan, F.; Jiang, C.; Yu, Y.; Guo, J.; Chai, Y.; Chen, Y. The spo0A-sinI-sinR regulatory circuit plays an essential role in biofilm formation, nematicidal activities, and plant protection in Bacillus cereus AR156. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2017, 30, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, W.; Zhao, S.-G.; Qian, S.-H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, M.-J.; Hu, W.-S.; Wang, J.; Hu, L.-X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of the quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator SinR affects the biosynthesis of menaquinone in Bacillus subtilis. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Luo, Y.; Adinkra, E.K.; Chen, Y.; Tao, W.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Wu, J.; Wu, C.; Liu, Y. Engineering a PhrC-RapC-SinR quorum sensing molecular switch for dynamic fine-tuning of menaquinone-7 synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Microb. Cell Factories 2025, 24, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, S.; Roessle, M.; Borriss, R.; Makarewicz, O.; Klinikum, A. AbrB antirepressor AbbA is a competitive inhibitor of AbrB-phyC interaction. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, E.; Morris, R.J.; Schor, M.; Earl, C.; Gillespie, R.M.; Bromley, K.M.; Sukhodub, T.; Clark, L.; Fyfe, P.K.; Serpell, L.C. Formation of functional, non-amyloidogenic fibres by recombinant Bacillus subtilis TasA. Mol. Microbiol. 2018, 110, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkelman, J.T.; Blair, K.M.; Kearns, D.B. RemA (YlzA) and RemB (YaaB) regulate extracellular matrix operon expression and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 3981–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkelman, J.T.; Bree, A.C.; Bate, A.R.; Eichenberger, P.; Gourse, R.L.; Kearns, D.B. RemA is a DNA-binding protein that activates biofilm matrix gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 88, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.-C.; Zhu, S.-Y.; Luo, M.-M.; Hu, X.-C.; Peng, C.; Huang, H.; Ren, L.-J. Intracellular response of Bacillus natto in response to different oxygen supply and its influence on menaquinone-7 biosynthesis. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, G.; Tang, H.; Sun, X.; Ni, W.; Yang, Q.; Wang, P.; Zheng, Z. Improvement of menaquinone-7 production by Bacillus subtilis natto in a novel residue-free medium by increasing the redox potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 7519–7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill-Bates, D.A. Chapter Five—The antioxidant glutathione. In Vitamins and Hormones; Litwack, G., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Volume 121, pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xue, S.; Dong, N.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S. Enhancing menaquinone-7 biosynthesis by optimized fermentation strategies and fed-batch cultivation of food-derived Bacillus subtilis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 5973–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneesha, M.; Subathra, D.C. A bioprocess optimization study to enhance the production of Menaquinone-7 using Bacillus subtilis MM26. Microb. Cell Factories 2025, 24, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, N.; Seifan, M.; Novin, D.; Berenjian, A. Development of a Menaquinone-7 enriched product through the solid-state fermentation of Bacillus licheniformis. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdinia, E.; Mamouri, S.J.; Puri, V.M.; Demirci, A.; Berenjian, A. Modeling of vitamin K (Menaquinoe-7) fermentation by Bacillus subtilis natto in biofilm reactors. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 17, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R.; Pan, G. Study on Fermentation Kinetics and Optimization of Feeding Strategy for Menaquinone-7 (Vitamin K2) Production by Bacillus subtilis. Adv. Comput. Mater. Sci. Res. 2025, 1, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Chen, M.; Coldea, T.E.; Yang, H.; Zhao, H. Soy protein hydrolysates induce menaquinone-7 biosynthesis by enhancing the biofilm formation of Bacillus subtilis natto. Food Microbiol. 2024, 124, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.-C.; Liu, W.-M.; Luo, M.-M.; Ren, L.-J.; Ji, X.-J.; Huang, H. Enhancing Menaquinone-7 Production by Bacillus natto R127 Through the Nutritional Factors and Surfactant. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 182, 1630–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.-X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.-P.; Tao, W.; Gao, X.-L.; Wu, C.-C.; Zhang, H.-M.; Han, R.-M.; Li, Y.-Q.; Liu, Y. Combination of SPH and SP80 prolongs the lifespan of Bacillus subtilis natto to enhance industrial menaquinone-7 biosynthesis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1578160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinker, A.; Babaria, D.; Jha, A.; Bajad, G.; Sukhanandi, J.; Patel, Y. Production of Vitamin K2-7 from Soybean Using Bacterial Fermentation and its Optimization at Different Salt Concentrations. Ind. Biotechnol. 2024, 20, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhao, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Zheng, Z. Coproduction of menaquinone-7 and nattokinase by Bacillus subtilis using soybean curd residue as a renewable substrate combined with a dissolved oxygen control strategy. Ann. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Cui, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; DU, G.; Lü, X.; Liu, L. Functional analysis of functional membrane microdomains in the biosynthesis of menaquinone-7. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 2215–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.-Y.; Qiu, Y.-B.; Zhang, X.-M.; Su, C.; Shi, J.-S.; Xu, Z.-H.; Li, H. The efficient green bio-manufacturing of Vitamin K2: Design, production and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 6336–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Peng, C.; Zhang, B.; Hu, X.; Milon, R.B.; Ren, L. Enhancing menaquinone-7 biosynthesis through strengthening precursor supply and product secretion. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 47, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushmitha, J.; Tharun Kumar, C.J.; Hrishikeshan, K.N.; Singh, T.; Kavya, T.; Vinutha, T. Metabolic Modeling and Flux Analysis: Intersection with Other Omics Techniques. In Microbial Metabolomics: Recent Developments, Challenges and Future Opportunities; Kaur, S., Dhiman, S., Tripathi, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 89–110. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-96-4824-5_5 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Kaste, J.A.M.; Shachar-Hill, Y. Accurate flux predictions using tissue-specific gene expression in plant metabolic modeling. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdo, N.; Volke, D.C.; McCloskey, D.; Nikel, P.I. Automating the design-build-test-learn cycle towards next-generation bacterial cell factories. New Biotechnol. 2023, 74, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, J.D.; Thiele, I.; Palsson, B.Ø. What is flux balance analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Bi, X.; Li, G.; Cui, S.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Lv, X.; Liu, L. Combinatorial metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for menaquinone-7 biosynthesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 3338–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikromvarasiri, N.; Noda, S.; Shirai, T.; Kondo, A. Investigation of two metabolic engineering approaches for (R,R)-2,3-butanediol production from glycerol in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Eng. 2023, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Source | Half-Life | Function | Metabolic Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K1 | Green leafy vegetables | Short (1–2 h) | Coagulation factor synthesis | Taking up by the liver for clotting | [4,5] |

| Vitamin K2 MK-4 | Animal liver | Middle (2.5 h) | Local tissue calcium regulation | Tachymetabolism | [4,5] |

| Egg yolk | |||||

| Vitamin K2 MK-7 | Natto Fermented foods | Long (68 h) | Systemic calcium metabolism regulation | Slow release | [4,5] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, S.; Sun, X.; Fan, T.; Lin, F.; Chi, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhao, C. Metabolic Engineering Strategy for Bacillus subtilis Producing MK-7. Foods 2025, 14, 4150. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234150

Wu S, Sun X, Fan T, Lin F, Chi Y, Yang H, Zhao C. Metabolic Engineering Strategy for Bacillus subtilis Producing MK-7. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4150. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234150

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Shiying, Xiuwen Sun, Tingwen Fan, Fei Lin, Yuan Chi, Huaiyi Yang, and Chunhui Zhao. 2025. "Metabolic Engineering Strategy for Bacillus subtilis Producing MK-7" Foods 14, no. 23: 4150. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234150

APA StyleWu, S., Sun, X., Fan, T., Lin, F., Chi, Y., Yang, H., & Zhao, C. (2025). Metabolic Engineering Strategy for Bacillus subtilis Producing MK-7. Foods, 14(23), 4150. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234150