Evolution of Secondary Metabolites in Eruca sativa from the Microgreen to the Reproductive Stage: An Integrative Multi-Platform Metabolomics Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Germplasm and Growing Conditions

2.2. Reagents and Solvents

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. UHPLC-Q-Exactive/MS and UHPLC-Q-Exactive/MS/MS Analysis

2.5. Compound Discoverer Data Analysis

2.6. GC-qMS Analysis

2.7. Multivariate Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. UHPLC-Q-Exactive/MS and UHPLC-Q-Exactive/MS/MS Analysis

| N° | Rt (min) | [M − H]− (m/z) | Molecular Formula | RMS Error (ppm) | MS/MS (m/z) | Compound | M | V | R | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.57 | 195.0502 | C6H12O7 | 0.9 | 75.0073/129.0180 | Gluconic acid | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [19] |

| 2 | 1.66 | 341.1088 | C12H22O11 | 2.9 | 179.0549/161.0444/143.0337 | Sucrose | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [20] |

| 3 | 1.82 | 333.0594 | C9H19O11P | −3.2 | 152.9950/241.0120/259.0239/181.0056/78.9576 | Phosphatidyl-myoinositol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [21] |

| 4 | 2.11 | 191.0187 | C6H8O7 | 0.3 | 111.0074/87.0073/129.0181 | Isocitric acid | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [22] |

| 5 | 2.36 | 323.0289 | C9H13O9N2P | 2.5 | 211.0010/78.9579/111.0189/96.9685 | 5′-UMP | ND | ND | ✓ | [23] |

| 6 | 2.57 | 436.0409 | C12H23O10NS3 | 0.7 | 96.9587/95.9509/178.0170/372.0423/74.9895/79.9558/259.0118 | Glucoraphanin | ✓ | ND | ✓ | [14] |

| 7 | 3.19 | 565.0479 | C15H24O17N2P2 | 2.2 | 323.0276/78.9577/96.9681/241.0116/158.9246/211.0012/ 272.9576/305.0149 | Uridine-5′-diphospho glucose | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [24] |

| 8 | 3.56 | 344.0402 | C10H12O7N5P | 3.2 | 150.0409/133.0148 | Cyclic GMP | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [25] |

| 9 | 4.66 | 315.0724 | C13H16O9 | 4.0 | 152.0102/108.0202 | Genistic acid glucoside | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [14] |

| 10 | 10.51 | 406.0307 | C11H21O9NS3 | 2.9 | 96.9587/95.9508/74.9896/79.9560/259.0119/114.0547 | Glucoiberverin | ✓ | ND | ✓ | [14] |

| 11 | 11.76 | 461.1311 | C19H26O13 | 3.4 | 163.0392/167.0338 | Saccharumoside C | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [26] |

| 12 | 11.89 | 711.0999 | C21H36O15N4S4 | 3.1 | 96.9587/306.0763/143.0451/179.0452/456.1617 | Glutathione disulfanyl butyl-GLS | ✓ | ND | ✓ | [27] |

| 13 | 12.20 | 209.9895 | C5H9O4NS2 | 2.8 | 95.9509 | Sulfuric acid, mono[(1-thioxo-4-penten-1-yl)azanyl] ester | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [14] |

| 14 | 12.92 | 395.0291 | C13H16O12S | −3.2 | 153.0181/241.0020 | Protocatechuic acid-O-sulfate-O-glucoside | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [28] |

| 15 | 13.71 | 325.0930 | C15H18O8 | 3.4 | 145.0282/163.0391 | p-Coumaric acid 4-O-glucoside | ✓ | ND | ND | [29] |

| 16 | 14.15 | 420.0465 | C12H23O9NS3 | 2.0 | 96.9587/74.9896/95.9508/128.0341/79.9560/259.0119 | Glucoerucin | ✓ | ND | ND | [14] |

| 17 | 14.32 | 817.2048 [(M + FA) − H]− | C33H40O21 | 1.8 | 609.1461/447.0930/285.0402 | Kaempferol 3-diglucoside 7-glucoside | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [30] |

| 18 | 14.91 | 355.1037 | C16H20O9 | 3.8 | 175.0391/193.0505 | Ferulic acid 4-O-glucoside | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [31] |

| 19 | 15.19 | 385.1143 | C17H22O10 | 2.1 | 205.0499/190.0263 | Sinapic acid glucoside | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [14] |

| 20 | 16.10 | 371.0986 | C16H20O10 | 3.4 | 121.0282/249.0620/113.0230 | Deacetylasperuloside | ✓ | ND | ND | [32] |

| 21 | 16.28 | 771.2015 | C33H40O21 | 4.0 | 285.0403 | Kaempferol 3-triglucoside | ND | ✓ | ✓ | [33,34] |

| 22 | 17.27 | 609.1442 | C27H30O16 | −1.2 | 285.0404/283.0243/476.0854 | Kaempferol-3,4′-diglucoside | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [30] |

| 23 | 17.58 | 639.1570 | C28H32O17 | 1.4 | 313.0352/476.0952/477.1036/285.0403 | Isorhamnetin-3,4′-diglucoside | ✓ | ND | ND | [30] |

| 24 | 17.70 | 993.2512 | C44H50O26 | 0.5 | 301.0349/463.0876 | Quercetin-3,4′-diglucoside 3′-(6-sinapoylglucoside) | ✓ | ND | ND | [14] |

| 25 | 17.79 | 977.2557 | C44H50O25 | 0.2 | 285.0399/653.1470/447.0950/429.0864 | Kaempferol 3-O-sinapoylsophoroside 7-O-glucoside | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [35] |

| 26 | 18.41 | 521.2034 | C26H34O11 | 2.1 | 341.1386 | Lariciresinol-4′-glucoside | ND | ✓ | ✓ | [36] |

| 27 | 18.8 | 477.0646 | C17H22O10N2S2 | 2.8 | 96.9587/95.9509/74.9896/79.9559/259.0110 | Neoglucobrassicin | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [14] |

| 28 | 19.22 | 187.0971 | C9H16O4 | 0.1 | 125.0959/123.0800/143.1068 | Azelaic acid | ND | ✓ | ND | [19] |

| 29 | 20.31 | 831.2001 | C38H40O21 | 2.7 | 301.0349/463.0883 | Quercetin 3-(6‴-sinapylhexoside-hexoside | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [37] |

| 30 | 20.67 | 815.2028 | C38H40O20 | −0.1 | 285.0403/447.0930 | Kaempferol 3-(2-sinapoylglucoside) 4′-glucoside | ND | ✓ | ND | [30] |

| 31 | 20.67 | 386.0406 | C12H21O9NS2 | 2.1 | 74.98974/96.9587/95.9508/79.9560/259.0119 | Glucobrassicanapin | ND | ✓ | ND | [38] |

| 32 | 20.72 | 405.0229 [M − 2H]2− | C22H40O18N2S6 | −1.5 | 96.9587/95.9509/74.9896/259.0131 | DMB-GLS | ✓ | ND | ✓ | [14] |

| 33 | 20.85 | 785.1945 | C37H38O19 | 2.7 | 285.0401 | Kaempferol 3-(feruloyldiglucoside) | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [39] |

| 34 | 24.39 | 327.2176 | C18H32O5 | 2.9 | 211.1331/229.1440/171.1019 | Trihydroxy octadecadienoic acid | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [14] |

| 35 | 22.49 | 504.1045 | C17H31O10NS3 | 2.6 | 96.9590/74.9898 | Unknown | ND | ND | ✓ | - |

| 36 | 22.78 | 507.0754 | C18H24O11N2S2 | 2.3 | 96.9588 | 1,4-Dimethoxyglucobrassicin | ND | ✓ | ✓ | [40] |

| 37 | 25.35 | 242.1760 | C13H25O3N | 3.2 | 225.1494/181.1587 | N-Octanoyl-L-valine | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [41] |

| 38 | 25.56 | 329.2335 | C18H34O59 | 1.2 | 211.1333/229.1438 | Trihydroxy-octadecanoic acid | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [14] |

| 39 | 27.04 | 253.1446 | C14H22O4 | 4.7 | 209.1540 | β-caryophyllinic acid | ND | ✓ | ND | [42] |

| 40 | 28.54 | 713.0869 | - | - | 96.9587/95.9509/456.8649/373.2574 | Unknown | ✓ | ND | ND | - |

| 41 | 29.26 | 293.1761 | C17H26O4 | 4.2 | 211.1540/236.1047/96.9586 | Gingerol | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [14] |

| 42 | 30.37 | 531.2808 [(M + FA) − H]− | C25H42O9 | 1.5 | 249.1855 | MGMG 16:3 | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [14] |

| 43 | 30.61 | 721.3648 [(M + FA) − H]− | C33H56O14 | 1.3 | 277.2169/397.1354/89.0230/59.0125/101.0230/71.0125 | DGMG 18:3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [14] |

| 44 | 31.65 | 723.3821 [(M + FA) − H]− | C33H58O14 | 3.9 | 279.2327 | Gingerglycolipid B | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [43] |

| 45 | 32.25 | 699.3821 [(M + FA) − H]− | C31H58O14 | 2.7 | 255.2331/89.0232/397.1351 | DGMG (16:0) | ND | ND | ✓ | [44] |

| 46 | 32.37 | 551.03198 | - | - | 96.9587/95.9509/74.9896/259.0125 | Unknown | ✓ | ND | ✓ | |

| 47 | 32.70 | 559.3117 [(M + FA) − H]− | C27H465O9 | 0.7 | 277.2169/253.0930 | MGMG 18:3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [14] |

| 48 | 33.07 | 452.2789 | C21H44O7NP | 4.0 | 255.2327/196.0372/214.0482 | l-PE 16:0 | ✓ | ✓ | ND | [45] |

| 49 | 33.63 | 291.1970 | C18H28O3 | 5.0 | 185.1177 | Oxo octadecatetraenoic acid | ✓ | ND | ND | [14] |

| 50 | 38.66 | 263.1291 | C15H20O4 | 5.0 | 219.1384 | (±)-Abscisic acid | ✓ | ND | ND | |

| 51 | 41.27 | 953.5477 [(M + FA) − H]− | C50H82O17 | 0.8 | 277.2169/249.1856/397.1350/101.0230 | DGDG (16:3; 18:3) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [14] |

| 52 | 43.19 | 981.5782 [(M + FA) − H]− | C52H86O17 | 0.1 | 277.2168/397.1349/101.0231 | DGDG (18:3; 18:3) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [14] |

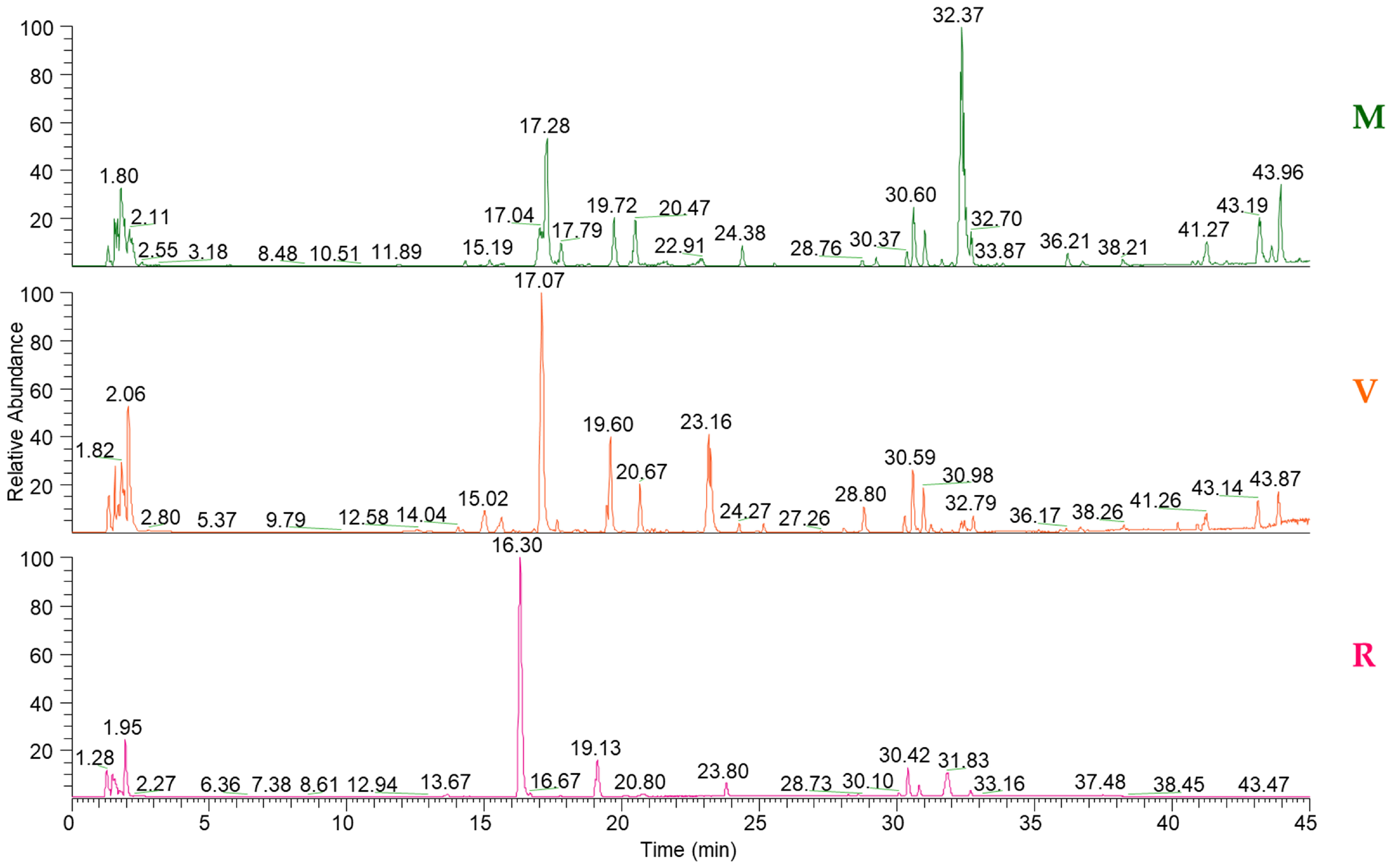

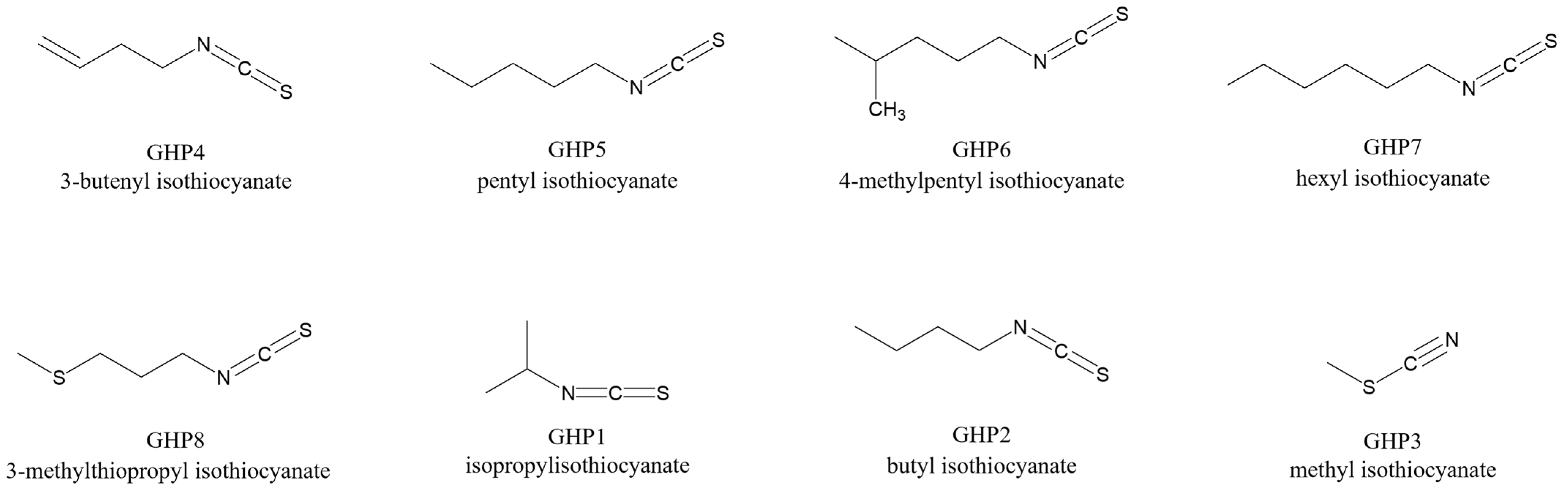

3.2. GC-qMS Analysis

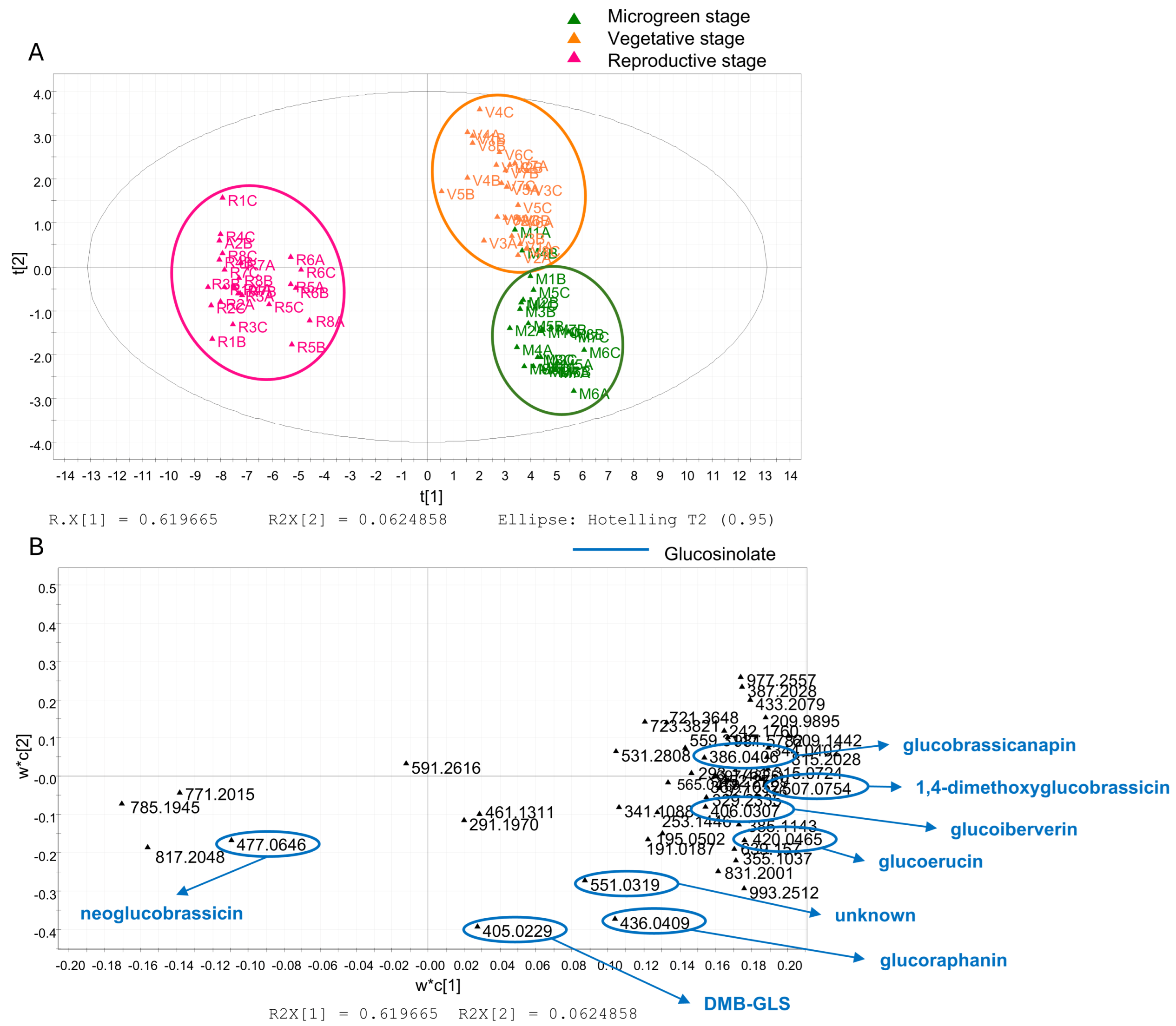

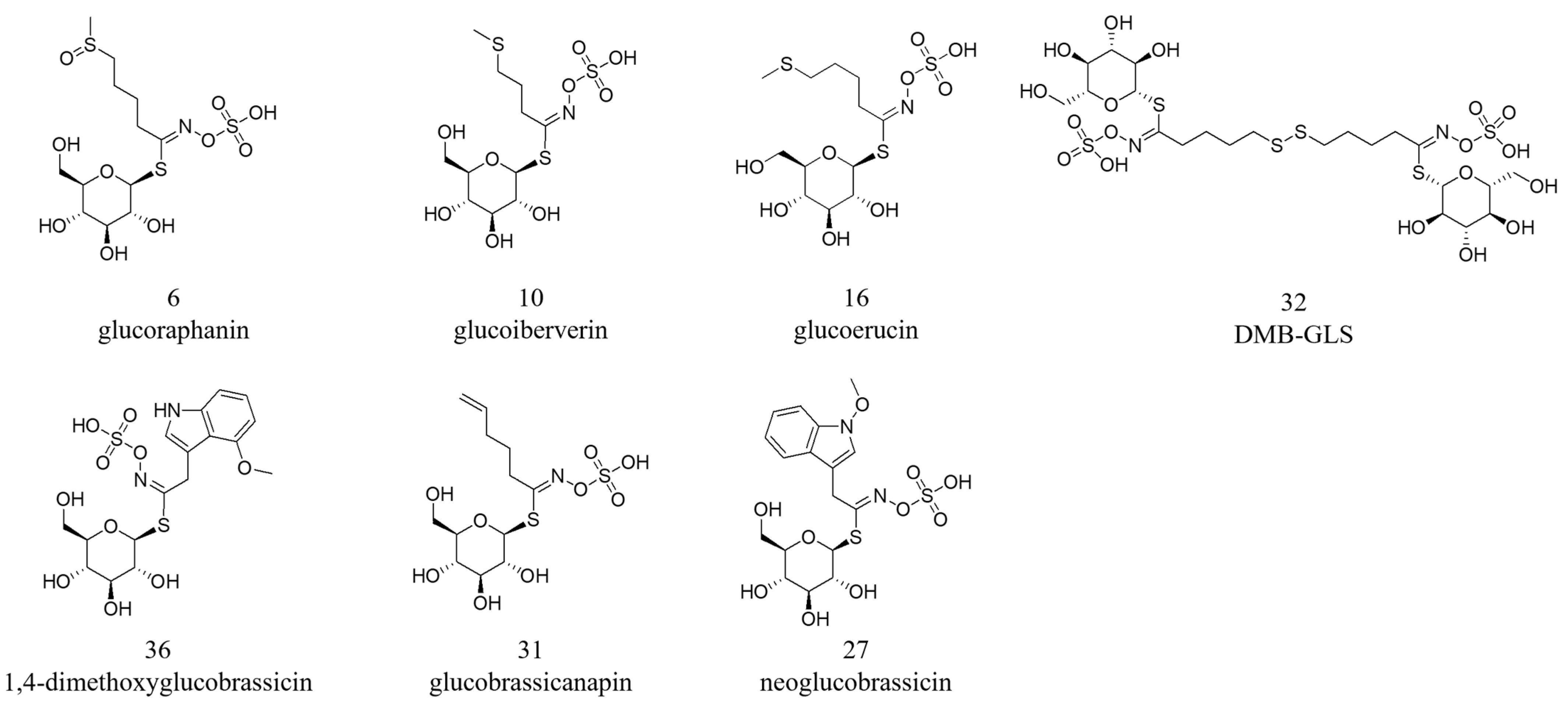

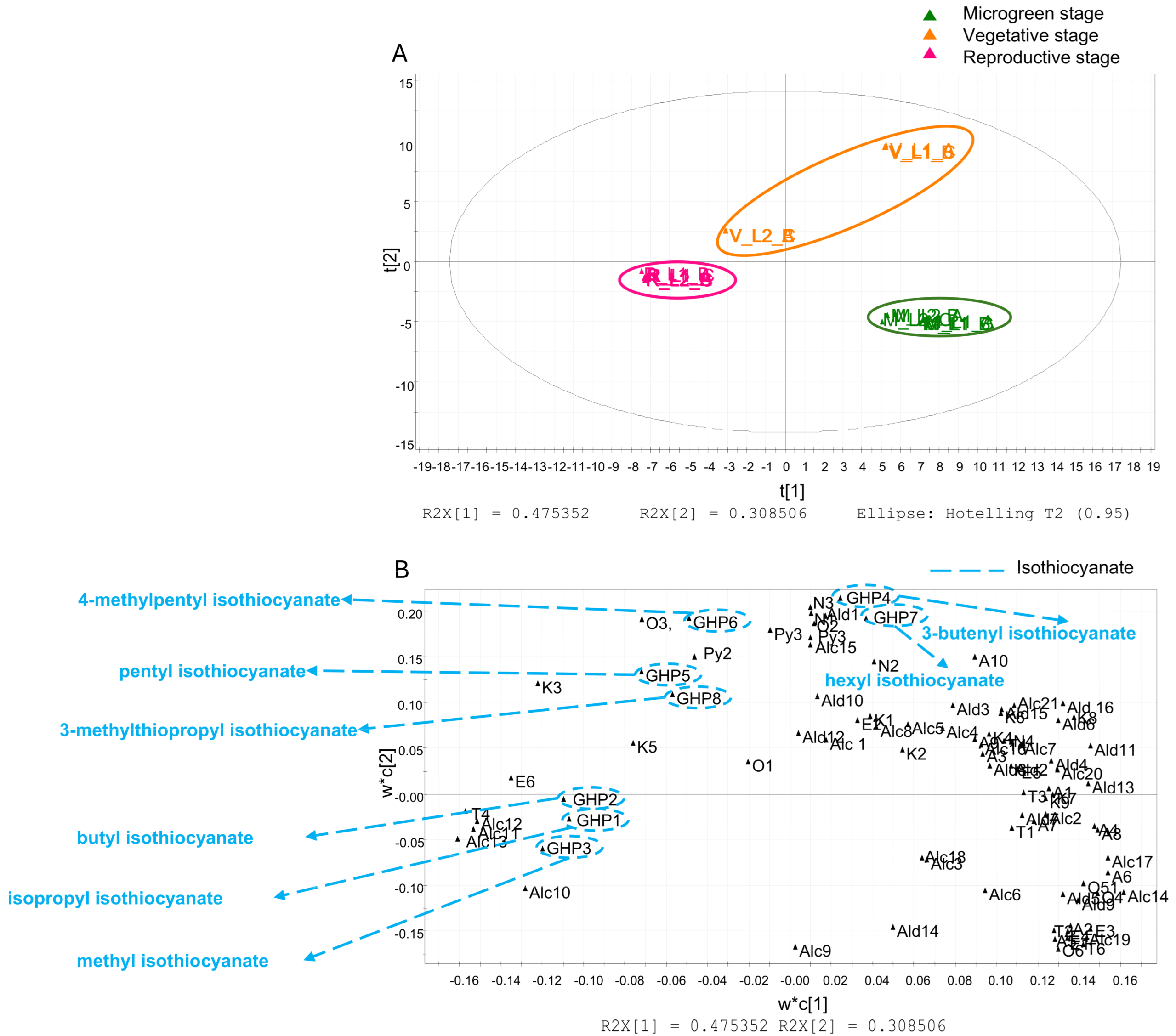

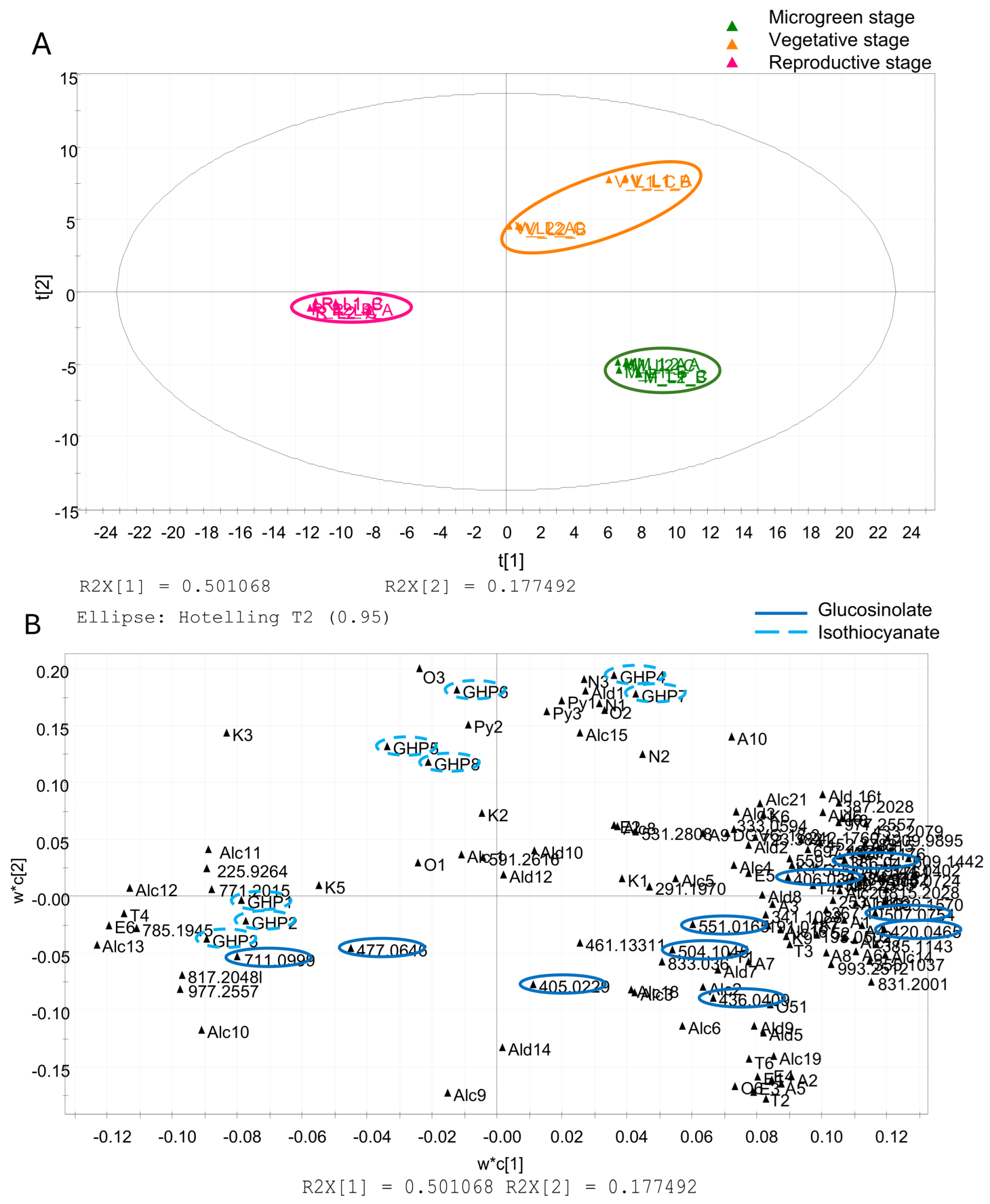

3.3. Multivariate Data Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- d’Aquino, L.; Lanza, B.; Gambale, E.; Sighicelli, M.; Menegoni, P.; Modarelli, G.; Rimauro, J.; Chianese, E.; Nenna, G.; Fasolino, T.; et al. Growth and metabolism of Basil grown in a new-concept microcosm under different lighting conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 299, 111035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wu, H.; Liang, R.; Huang, S.; Meng, L.; Zhang, M.; Xie, F.; Zhu, H. Light regulates the synthesis and accumulation of plant secondary metabolites. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1644472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, L.P.; Koley, T.K.; Tripathi, A.; Singh, S. Antioxidant Potentiality and Mineral Content of Summer Season Leafy Greens: Comparison at Mature and Microgreen Stages Using Chemometric. Agric. Res. 2019, 8, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilahy, R.; Tlili, I.; Pék, Z.; Montefusco, A.; Siddiqui, M.W.; Homa, F.; Hdider, C.; R’Him, T.; Lajos, H.; Lenucci, M.S. Pre- and Post-harvest Factors Affecting Glucosinolate Content in Broccoli. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yan, C.; Khan, A.; Fei, S.; Lei, T.; Xu, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, R.; Hui, M. Distribution of Indolic Glucosinolates in Different Developmental Stages and Tissues of 13 Varieties of Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Sun, J.; Hu, Z.; Cheng, C.; Lin, S.; Zou, H.; Yan, X. Variation in Glucosinolate Accumulation among Different Sprout and Seedling Stages of Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica). Plants 2022, 11, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.; Wagstaff, C. Rocket science: A review of phytochemical & health-related research in Eruca & Diplotaxis species. Food Chem. X 2019, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, G.; Sharma, V. Eruca sativa (L.): Botanical Description, Crop Improvement, and Medicinal Properties. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2014, 20, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sulivany, B.S.A.; Ahmed, D.Y.; Naif, R.O.; Omer, E.A.; Saleem, P.M. Phytochemical Profile of Eruca sativa and Its Therapeutic Potential in Disease Prevention and Treatment. Glob. Acad. J. Agric. Biosci. 2024, 6, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Liu, X.; Lei, P.; Zhang, X.; Shan, Y. Microbiota: A mediator to transform glucosinolate precursors in cruciferous vegetables to the active isothiocyanates. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhajed, S.; Misra, B.B.; Tello, N.; Chen, S. Chemodiversity of the Glucosinolate-Myrosinase System at the Single Cell Type Resolution. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, P.; Spinozzi, S.; Pagnotta, E.; Lazzeri, L.; Ugolini, L.; Camborata, C.; Roda, A. Development of a liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous analysis of intact glucosinolates and isothiocyanates in Brassicaceae seeds and functional foods. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1428, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.; Wagstaff, C. Glucosinolates, myrosinase hydrolysis products, and flavonols found in rocket (Eruca sativa and Diplotaxis tenuifolia). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4481–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, M.A.; Cerulli, A.; Montoro, P.; Piacente, S. Metabolite Profiling for Typization of “Rucola della Piana del Sele” (PGI), Eruca sativa, through UHPLC-Q-Exactive-Orbitrap-MS/MS Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.M.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis: Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowicz, S.; Oszmiański, J.; Rapak, A.; Ochmian, I. Profile and Content of Phenolic Compounds in Leaves, Flowers, Roots, and Stalks of Sanguisorba officinalis L. Determined with the LC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Analysis and Their In Vitro Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Antiproliferative Potency. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugo, P.; Donato, P.; Cacciola, F.; Germanò, M.P.; Rapisarda, A.; Mondello, L. Characterization of the polyphenolic fraction of Morus alba leaves extracts by HPLC coupled to a hybrid IT-TOF MS system. J. Sep. Sci. 2009, 32, 3627–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellaneta, A.; Losito, I.; Cisternino, G.; Leoni, B.; Santamaria, P.; Calvano, C.D.; Bianco, G.; Cataldi, T.R.I. All Ion Fragmentation Analysis Enhances the Untargeted Profiling of Glucosinolates in Brassica Microgreens by Liquid Chromatography and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 33, 2108–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, K.; Nilofar; Mohamed, A.; Świątek, Ł.; Hryć, B.; Sieniawska, E.; Rajtar, B.; Ferrante, C.; Menghini, L.; Zengin, G.; et al. Evaluating Phytochemical Profiles, Cytotoxicity, Antiviral Activity, Antioxidant Potential, and Enzyme Inhibition of Vepris boiviniana Extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Napolitano, A.; Bruno, M.; Geraci, A.; Schicchi, R.; Leporini, M.; Tundis, R.; Piacente, S. LC-ESI/HRMS analysis of glucosinolates, oxylipins and phenols in Italian rocket salad (Diplotaxis erucoides subsp. erucoides (L.) DC.) and evaluation of its healthy potential. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 5872–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otify, A.M.; ElBanna, S.A.; Eltanany, B.M.; Pont, L.; Benavente, F.; Ibrahim, R.M. A comprehensive analytical framework integrating liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry metabolomics with chemometrics for metabolite profiling of lettuce varieties and discovery of antibacterial agents. Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Jiang, W.; Niu, Y.; Shao, Q.; Gao, L.; Zhao, Q.; Yan, L.; Wang, S. Comparison of the anti-inflammatory active constituents and hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids in two Senecio plants and their preparations by LC–UV and LC–MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015, 115, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brabandere, H.; Forsgard, N.; Israelsson, L.; Petterson, J.; Rydin, E.; Waldebäck, M.; Sjöberg, P.J.R. Screening for Organic Phosphorus Compounds in Aquatic Sediments by Liquid Chromatography Coupled to ICP-AES and ESI-MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 6689–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.N.; Wang, L.; Shi, Z.Q.; Li, P.; Li, H.J. A metabolomic strategy based on integrating headspace gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to differentiate the five cultivars of Chrysanthemum flower. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 9074–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, M.; Ding, H.; Li, W.; Yin, J.; Lin, R.; Wu, X.; Han, L.; Yang, W.; Bie, S.; et al. Integration of non-targeted multicomponent profiling, targeted characteristic chromatograms and quantitative to accomplish systematic quality evaluation strategy of Huo-Xiang-Zheng-Qi oral liquid. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 236, 115715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, H.; Peng, H.; Chen, H.; Xie, H.-r.; Deng, Z. Rapid characterization of chemical constituents in Radix tetrastigma, a functional herbal mixture, before and after metabolism and their antioxidant/antiproliferative activities. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Xiao, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Q. An integrated analytical approach based on enhanced fragment ions interrogation and modified Kendrick mass defect filter data mining for in-depth chemical profiling of glucosinolates by ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography coupled with Orbitrap high resolution mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1639, 461903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shi, Z.; Song, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhao, M.; Tu, P.; Jiang, Y. Source attribution and structure classification-assisted strategy for comprehensively profiling Chinese herbal formula: Ganmaoling granule as a case. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1464, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Asgher, Z.; Cottrell, J.J.; Dunshea, F.R. Screening and Characterization of Phenolic Compounds from Selected Unripe Fruits and Their Antioxidant Potential. Molecules 2023, 29, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Wagstaff, C. Identification and quantification of glucosinolate and flavonol compounds in rocket salad (Eruca sativa, Eruca vesicaria and Diplotaxis tenuifolia) by LC–MS: Highlighting the potential for improving nutritional value of rocket crops. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntsoane, M.L.L.; Manhivi, V.E.; Shoko, T.; Seke, F.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Sivakumar, D. Brassica microgreens cabbage (Brassica oleracea), radish (Raphanus sativus) and rocket (Eruca vesicaria) (L.) Cav: Application of red-light emitting diodes lighting during postharvest storage and in vitro digestion on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amessis-Ouchemoukh, N.; Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Madani, K.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Tentative characterisation of iridoids, phenylethanoid glycosides and flavonoid derivatives from Globularia alypum L. (Globulariaceae) leaves by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Phytochem. Anal. 2014, 25, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, G.B.; Raes, K.; Vanhoutte, H.; Coelus, S.; Smagghe, G.; Van Camp, J. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry coupled with multivariate analysis for the characterization and discrimination of extractable and nonextractable polyphenols and glucosinolates from red cabbage and Brussels sprout waste streams. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1402, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davì, F.; Taviano, M.F.; Acquaviva, R.; Malfa, G.A.; Cavò, E.; Arena, P.; Ragusa, S.; Cacciola, F.; El Majdoub, Y.O.; Mondello, L.; et al. Chemical Profile, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activity of a Phenolic-Rich Fraction from the Leaves of Brassica fruticulosa subsp. fruticulosa (Brassicaceae) Growing Wild in Sicily (Italy). Molecules 2023, 28, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Zietz, M.; Schreiner, M.; Rohn, S.; Kroh, L.W.; Krumbein, A. Identification of complex, naturally occurring flavonoid glycosides in kale (Brassica oleracea var. sabellica) by high-performance liquid chromatography diode-array detection/electrospray ionization multi-stage mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 24, 2009–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-Z.; Sun, J.; Chen, P.; Zhang, R.-W.; Fan, X.-E.; Li, L.-W.; Harnly, J.M. Profiling of Glucosinolates and Flavonoids in Rorippa indica (Linn.) Hiern. (Cruciferae) by UHPLC-PDA-ESI/HRMSn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6118–6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, G.; Shi, W.; Fang, X.; Han, L.; Cao, Y. Anti-Alzheimer’s disease active components screened out and identified from Hedyotis diffusa combining bioaffinity ultrafiltration LC-MS with acetylcholinesterase. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 296, 115460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.N.; Mellon, F.A.; Kroon, P.A. Screening crucifer seeds as sources of specific intact glucosinolates using ion-pair high-performance liquid chromatography negative ion electrospray mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veremeichik, G.N.; Grigorchuk, V.P.; Makhazen, D.S.; Subbotin, E.P.; Kholin, A.S.; Subbotina, N.I.; Bulgakov, D.V.; Kulchin, Y.N.; Bulgakov, V.P. High production of flavonols and anthocyanins in Eruca sativa (Mill) Thell plants at high artificial LED light intensities. Food Chem. 2023, 408, 135216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awadelkareem, A.M.; Al-Shammari, E.; Elkhalifa, A.E.O.; Adnan, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Snoussi, M.; Khan, M.I.; Azad, Z.R.A.A.; Patel, M.; Ashraf, S.A. Phytochemical and In Silico ADME/Tox Analysis of Eruca sativa Extract with Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Anticancer Potential against Caco-2 and HCT-116 Colorectal Carcinoma Cell Lines. Molecules 2022, 27, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phosri, S.; Kiattisin, K.; Intharuksa, A.; Janon, R.; Na Nongkhai, T.; Theansungnoen, T. Anti-Aging, Anti-Acne, and Cytotoxic Activities of Houttuynia cordata Extracts and Phytochemicals Analysis by LC-MS/MS. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto Araujo, N.M.; Arruda, H.S.; Dos Santos, F.N.; de Morais, D.R.; Pereira, G.A.; Pastore, G.M. LC-MS/MS screening and identification of bioactive compounds in leaves, pulp and seed from Eugenia calycina Cambess. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Tu, P. Spatial distribution of differential metabolites in different parts of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, M.; Cerulli, A.; Pizza, C.; Piacente, S. Pouteria lucuma Pulp and Skin: In Depth Chemical Profile and Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Fang, N.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H.; Ronis, M.; Badger, T.M. In Vitro Actions on Human Cancer Cells and the Liquid Chromatography−Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry Fingerprint of Phytochemicals in Rice Protein Isolate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4482–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partap, M.; Sharma, D.; Hn, D.; Thakur, M.; Verma, V.; Ujala; Bhargava, B. Microgreen: A tiny plant with superfood potential. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 107, 105697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.W. Sprouts and Microgreens—Novel Food Sources for Healthy Diets. Plants 2022, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstock, U.; Burow, M. Glucosinolate breakdown in Arabidopsis: Mechanism, regulation and biological significance. Arab. Book 2010, 8, e0134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Lakra, N.; Mishra, S.; Ahlawat, Y. Unraveling the potential of glucosinolates for nutritional enhancement and stress tolerance in Brassica crops. Veg. Res. 2024, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taviano, M.F.; Melchini, A.; Filocamo, A.; Costa, C.; Catania, S.; Raciti, R.; Saha, S.; Needs, P.; Bisignano, G.G.; Miceli, N. Contribution of the Glucosinolate Fraction to the Overall Antioxidant Potential, Cytoprotection against Oxidative Insult and Antimicrobial Activity of Eruca sativa Mill. Leaves Extract. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2017, 13, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barillari, J.; Canistro, D.; Paolini, M.; Ferroni, F.; Pedulli, G.F.; Iori, R.; Valgimigli, L. Direct antioxidant activity of purified glucoerucin, the dietary secondary metabolite contained in rocket (Eruca sativa Mill.) seeds and sprouts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2475–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, M. Methods of Modifying the Content of Glucosinolates and Their Derivatives in Sprouts and Microgreens During Their Cultivation and Postharvest Handling. Int. J. Food Sci. 2025, 2025, 2133668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Liu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, H.; Wang, Q. Variation of glucosinolates in three edible parts of Chinese kale (Brassica alboglabra Bailey) varieties. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Yu, L.; Pham, Q.; Sun, J.; Chen, P.; Yokoyama, W.; Yu, L.L.; Luo, Y.S.; et al. Red cabbage microgreens lower circulating low-density lipoprotein (LDL), liver cholesterol, and inflammatory cytokines in mice fed a high-fat diet. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 9161–9171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Tan, W.K.; Du, Y.; Lee, H.W.; Liang, X.; Lei, J.; Striegel, L.; Weber, N.; Rychlik, M.; Ong, C.N. Nutritional metabolites in Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis var. parachinensis (choy sum) at three different growth stages: Microgreen, seedling and adult plant. Food Chem. 2021, 357, 129535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Li, N.; Xu, M.; Miyamoto, T.; Liu, J. Sulforaphane suppresses metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer cells by targeting the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kensler, T.W.; Egner, P.A.; Agyeman, A.S.; Visvanathan, K.; Groopman, J.D.; Chen, J.-G.; Chen, T.-Y.; Fahey, J.W.; Talalay, P. Keap1–Nrf2 signaling: A target for cancer prevention by sulforaphane. Nat. Prod. Cancer Prev. Ther. 2012, 329, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, Y.S. Regulation of the Keap1/Nrf2 system by chemopreventive sulforaphane: Implications of posttranslational modifications. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2011, 1229, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Xu, Z.; Sun, Q.; Iniguez, A.B.; Du, M.; Zhu, M.J. Broccoli-derived glucoraphanin activates AMPK/PGC1α/NRF2 pathway and ameliorates dextran-sulphate-sodium-induced colitis in mice. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gendy, A.A.; Nematallah, K.A.; Zaghloul, S.S.; Ayoub, N.A. Glucosinolates profile, volatile constituents, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic activities of Lobularia libyca. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 3257–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citi, V.; Piragine, E.; Pagnotta, E.; Ugolini, L.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Testai, L.; Ghelardini, C.; Lazzeri, L.; Calderone, V.; Martelli, A. Anticancer properties of erucin, an H2 S-releasing isothiocyanate, on human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells (AsPC-1). Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, I.; Smimmo, M.; d’Emmanuele di Villa Bianca, R.; Bucci, M.; Cirino, G.; Panza, E.; Brancaleone, V. Erucin, an H2S-Releasing Isothiocyanate, Exerts Anticancer Effects in Human Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells Triggering Autophagy-Dependent Apoptotic Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, A.; Piragine, E.; Gorica, E.; Citi, V.; Testai, L.; Pagnotta, E.; Lazzeri, L.; Pecchioni, N.; Ciccone, V.; Montanaro, R.; et al. The H2S-Donor Erucin Exhibits Protective Effects against Vascular Inflammation in Human Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flori, L.; Montanaro, R.; Pagnotta, E.; Ugolini, L.; Righetti, L.; Martelli, A.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Ghelardini, C.; Brancaleone, V.; Testai, L.; et al. Erucin Exerts Cardioprotective Effects on Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury through the Modulation of mitoKATP Channels. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testai, L.; Pagnotta, E.; Piragine, E.; Flori, L.; Citi, V.; Martelli, A.; Mannelli, L.D.C.; Ghelardini, C.; Matteo, R.; Suriano, S.; et al. Cardiovascular benefits of Eruca sativa Mill. Defatted seed meal extract: Potential role of hydrogen sulfide. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 2616–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.; Kitsopanou, E.; Oloyede, O.O.; Lignou, S. Important Odorants of Four Brassicaceae Species, and Discrepancies between Glucosinolate Profiles and Observed Hydrolysis Products. Foods 2021, 10, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrandrea, L.; Amodio, M.L.; Pati, S.; Colelli, G. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging and temperature abuse on flavor related volatile compounds of rocket leaves (Diplotaxis tenuifolia L.). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2433–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffo, A.; Masci, M.; Moneta, E.; Nicoli, S.; Sánchez Del Pulgar, J.; Paoletti, F. Characterization of volatiles and identification of odor-active compounds of rocket leaves. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metabolite | Code | RIsp a/RIt b | ID c | M | V | R | Metabolite | Code | RIsp a/RIt b | ID c | M | V | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketones | |||||||||||||

| Acetone | K1 | 812/816 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | trans-2-Hexen-1-ol | Alc13 | 1394/1399 | RI/MS/S | ND | ND | ✓ |

| 2-Butanone | K2 | 905/910 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1-Octen-3-ol | Alc14 | 1446/1448 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| 3-Pentanone | K3 | 980/997 | RI/MS/S | ND | ✓ | ✓ | 1-Heptanol | Alc15 | 1460/1460 | RI/MS/S | ND | ✓ | ND |

| 4-Methyl-2-pentanone | K4 | 1010/1019 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2-Ethyl-1-hexanol | Alc16 | 1484/1488 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 1-Penten-3-one | K5 | 1019/1021 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,6-Dimethylcyclohexanol | Alc17 | 1111/1099 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2,3-Pentanedione | K6 | 1050/1050 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2-Furanmethanol | Alc18 | 1666/1661 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ND | ND |

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | K7 | 1348/1342 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Benzenemethanol, .alpha.-methyl | Alc19 | 2093/2092 | RI/MS | ✓ | ND | ND |

| 3,5-Octadien-2-one | K8 | 1524/1525 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Benzenmethanol | Alc20 | 1864/1861 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| Acetophenone | K9 | 1660/1700 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Benzenethanol | Alc21 | 1880/1881 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| Esters | Terpenes | ||||||||||||

| Methyl acetate | E1 | 839/800 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ND | ND | Limonene | T1 | 1204/1204 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ethyl acetate | E2 | 863/875 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1.8-Cineol | T2 | 1198/1199 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ND | ND |

| 2-Methyl-2-butenoate | E3 | 1175/1188 | RI/MS | ✓ | ND | ND | Linalool | T3 | 1532/1529 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| Methyl hexanoate | E4 | 1190/1190 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ND | ND | β-Cyclocitral | T4 | 1582/1579 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Methyl-3-hexenoate | E5 | 1253/1258 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND | Veratrol | T5 | 1706/1700 | RI/MS | ND | ND | ✓ |

| cis-3-Hexenyl acetate | E6 | 1321/1320 | RI/MS/S | ND | ND | ✓ | β-Ionone | T6 | 1909/1910 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ND | ND |

| Aldehydes | Glucosinolate Hydrolysis Products (GHPs) | ||||||||||||

| Butanal | Ald1 | 883/880 | RI/MS/S | ND | ✓ | ND | Isopropyl ITC | GHP1 | 1177/1167 | RI/MS/S | ND | ND | ✓ |

| 2-Methyl butanal | Ald2 | 919/923 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND | Butyl ITC | GHP2 | 1308/1300 | RI/MS/S | ND | ND | ✓ |

| 3-Methyl butanal | Ald3 | 920/922 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND | Methyl ITC | GHP3 | 1228/1230 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pentanal | Ald4 | 1013/1013 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND | 3-Butenyl ITC | GHP4 | 1459/1448 | RI/MS | ND | ✓ | ND |

| 2-Butenal | Ald5 | 1035/1033 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pentyl ITC | GHP5 | 2242/2250 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hexanal | Ald6 | 1084/1082 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4-Methylpentyl ITC | GHP6 | 1529/1531 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2-Pentenal | Ald7 | 1140/1150 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Hexyl ITC | GHP7 | 1588/1600 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Heptanal | Ald8 | 1188/1190 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3-Methylthiopropyl ITC | GHP8 | 1979/1980 | RI/MS/S | ND | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2-Hexenal | Ald9 | 1242/1250 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N-compounds | ||||||

| Octanal | Ald10 | 1286/1283 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Hexanitrile | N1 | 1315/1300 | RI/MS/S | ND | ✓ | ND |

| 2-Heptenal | Ald11 | 1323/1326 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND | 5-Methyl-hexanitrile | N2 | 1350/1350 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| Nonanal | Ald12 | 1390/1380 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Heptanitrile | N3 | 1405/1404 | RI/MS/S | ND | ✓ | ND |

| 2,4-Heptadienal | Ald13 | 1464/1460 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Butanenitrile, 4-(methylthio)- | N4 | 1812/1810 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| Decanal | Ald14 | 1506/1502 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Acids | ||||||

| Benzaldehyde | Ald15 | 1530/1530 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND | Acetic acid | A1 | 1445/1445 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| Benzenacetaldehyde | Ald16 | 1616/1621 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ND | 2,2-Dimethylpropanoic acid | A2 | 1227/1225 | RI/MS | ✓ | ND | ND |

| Pyrazines | Butanoic acid | A3 | 1637/1635 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND | ||||||

| 2-Methoxy-3-(1-methylethyl)pyrazine | Py1 | 1509/1500 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2-Methylbutanoic acid | A4 | 1682/1680 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| 2-Methoxy-3-(1-methylpropyl)pyrazine | Py2 | 1514/1520 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pentanoic acid | A5 | 1733/1729 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ND | ND |

| 2-Methoxy-3-(2-methylpropyl)pyrazine | Py3 | 1492/1151 | RI/MS | ND | ✓ | ✓ | Hexanoic acid | A6 | 1813/1813 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Alcohols | 3-Hexenoic acid | A7 | 1942/1940 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 2-Propanol | Alc1 | 975/974 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2-Hexenoic acid | A8 | 1042/1043 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| Ethanol | Alc2 | 955/945 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Octanoic acid | A9 | 2055/2050 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| 2-Methyl-1-propanol | Alc3 | 1097/1095 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ND | ND | Nonanoic acid | A10 | 2174/2178 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| 1-Butanol | Alc4 | 1125/1125 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Others | ||||||

| 1-Penten-3-ol | Alc5 | 1188/1189 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2-Ethylfuran | O1 | 950/947 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Isoamyl alcohol | Alc6 | 1222/1226 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ND | ND | Toluene | O2 | 1035/1035 | RI/MS/S | ND | ✓ | ND |

| 1-Pentanol | Alc7 | 1260/1271 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Tetrahydrothiophene | O3 | 1077/1073 | RI/MS | ND | ✓ | ✓ |

| trans-2-Penten-1-ol | Alc8 | 1335/1341 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2-Butoxyethanol | O4 | 1405/1411 | RI/MS | ✓ | ✓ | ND |

| cis-2-Penten-1-ol | Alc9 | 1272/1270 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1,3-Di-tert-butylbenzene | O5 | 1426/1428 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 1-Hexanol | Alc10 | 1340/1341 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5-Ethyl-2(5H)-furanone | O6 | 1910/1907 | RI/MS | ✓ | ND | ✓ |

| trans-3-Hexen-1-ol | Alc11 | 1386/1386 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| cis-3-Hexen-1-ol | Alc12 | 1390/1389 | RI/MS/S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monzillo, F.; Della Mura, B.; Matarazzo, C.; Crescenzi, M.A.; Piacente, S.; d’Aquino, L.; Cozzolino, R.; Montoro, P. Evolution of Secondary Metabolites in Eruca sativa from the Microgreen to the Reproductive Stage: An Integrative Multi-Platform Metabolomics Approach. Foods 2025, 14, 4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234148

Monzillo F, Della Mura B, Matarazzo C, Crescenzi MA, Piacente S, d’Aquino L, Cozzolino R, Montoro P. Evolution of Secondary Metabolites in Eruca sativa from the Microgreen to the Reproductive Stage: An Integrative Multi-Platform Metabolomics Approach. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234148

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonzillo, Francesca, Brigida Della Mura, Cristina Matarazzo, Maria Assunta Crescenzi, Sonia Piacente, Luigi d’Aquino, Rosaria Cozzolino, and Paola Montoro. 2025. "Evolution of Secondary Metabolites in Eruca sativa from the Microgreen to the Reproductive Stage: An Integrative Multi-Platform Metabolomics Approach" Foods 14, no. 23: 4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234148

APA StyleMonzillo, F., Della Mura, B., Matarazzo, C., Crescenzi, M. A., Piacente, S., d’Aquino, L., Cozzolino, R., & Montoro, P. (2025). Evolution of Secondary Metabolites in Eruca sativa from the Microgreen to the Reproductive Stage: An Integrative Multi-Platform Metabolomics Approach. Foods, 14(23), 4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234148