Effects of Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium verticillioides Infection on Sweet Corn Quality During Postharvest Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Pathogen Spore Suspension

2.3. Postharvest Treatment and Sampling of Sweet Corn

2.4. Visual Assessment of Sweet Corn

2.5. Color Measurement of Sweet Corn

2.6. Hardness Measurement of Sweet Corn

2.7. Measurement of Weight Loss Rate in Sweet Corn

2.8. Measurement of MDA Content in Sweet Corn

2.9. Assessment of Surface Fungal Spore Count in Sweet Corn

2.10. Measurement of Soluble Protein Content in Sweet Corn

2.11. Measurement of Soluble Sugar Content in Sweet Corn

2.12. Data Statistical Analysis and Processing Methods

3. Results

3.1. Visual Observation of Sweet Corn

3.2. Color Variation in Sweet Corn

3.3. Hardness Change of Sweet Corn

3.4. Changes in Weight Loss Rate of Sweet Corn

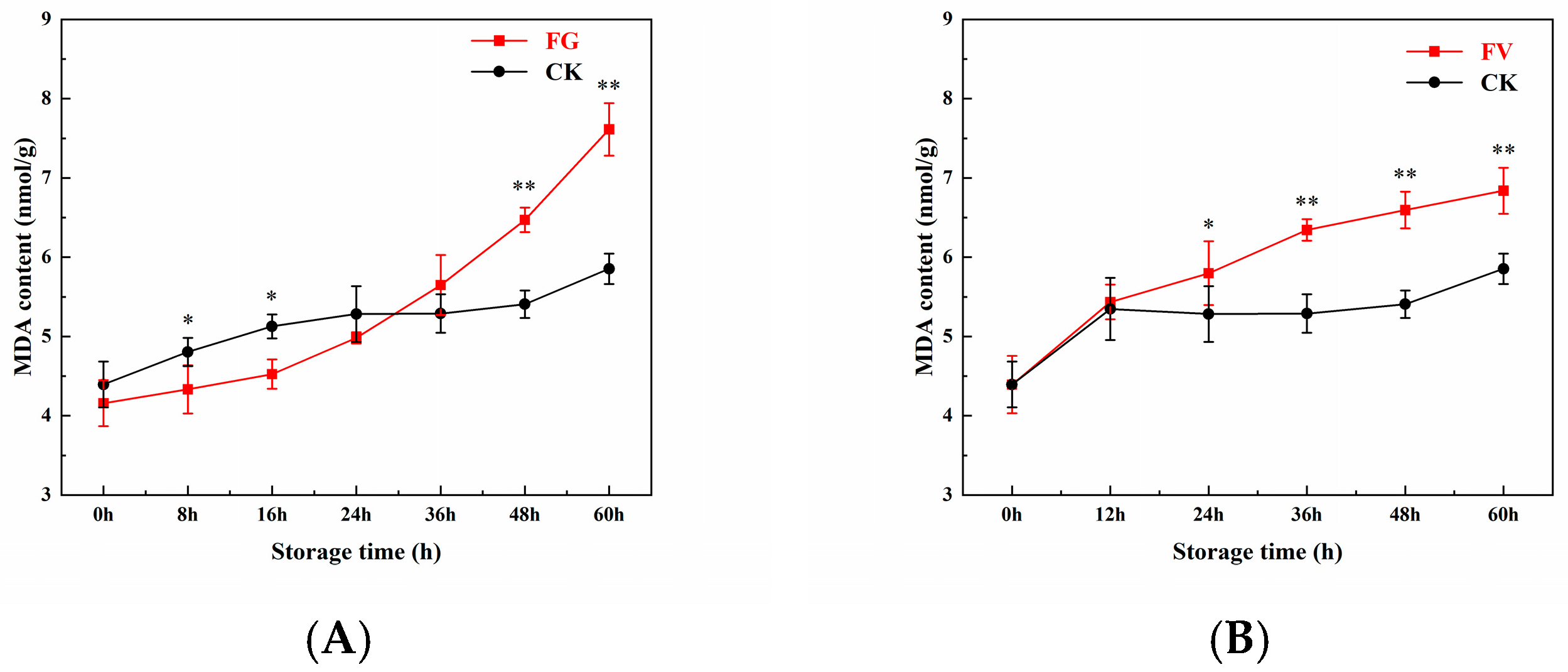

3.5. Changes in MDA Content of Sweet Corn

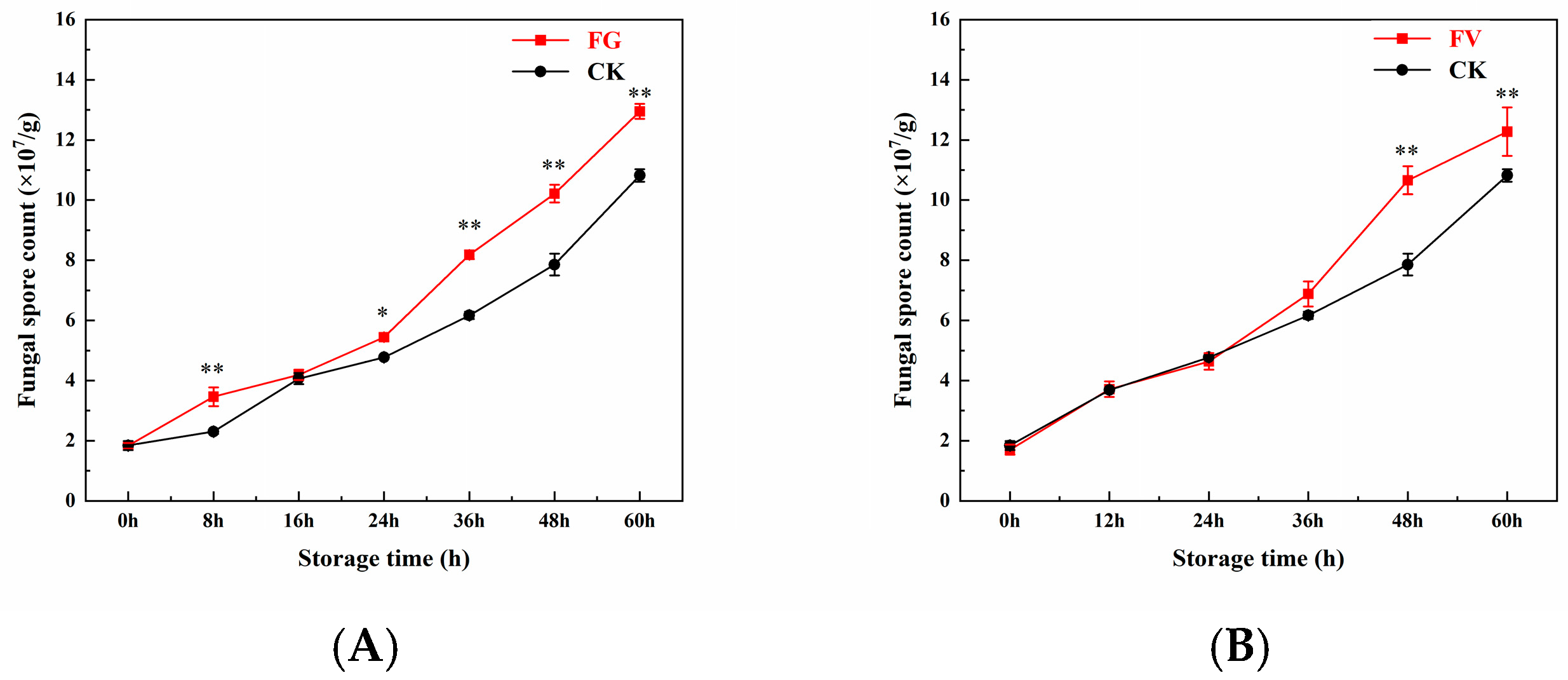

3.6. Changes in Surface Fungal Spore Count of Sweet Corn

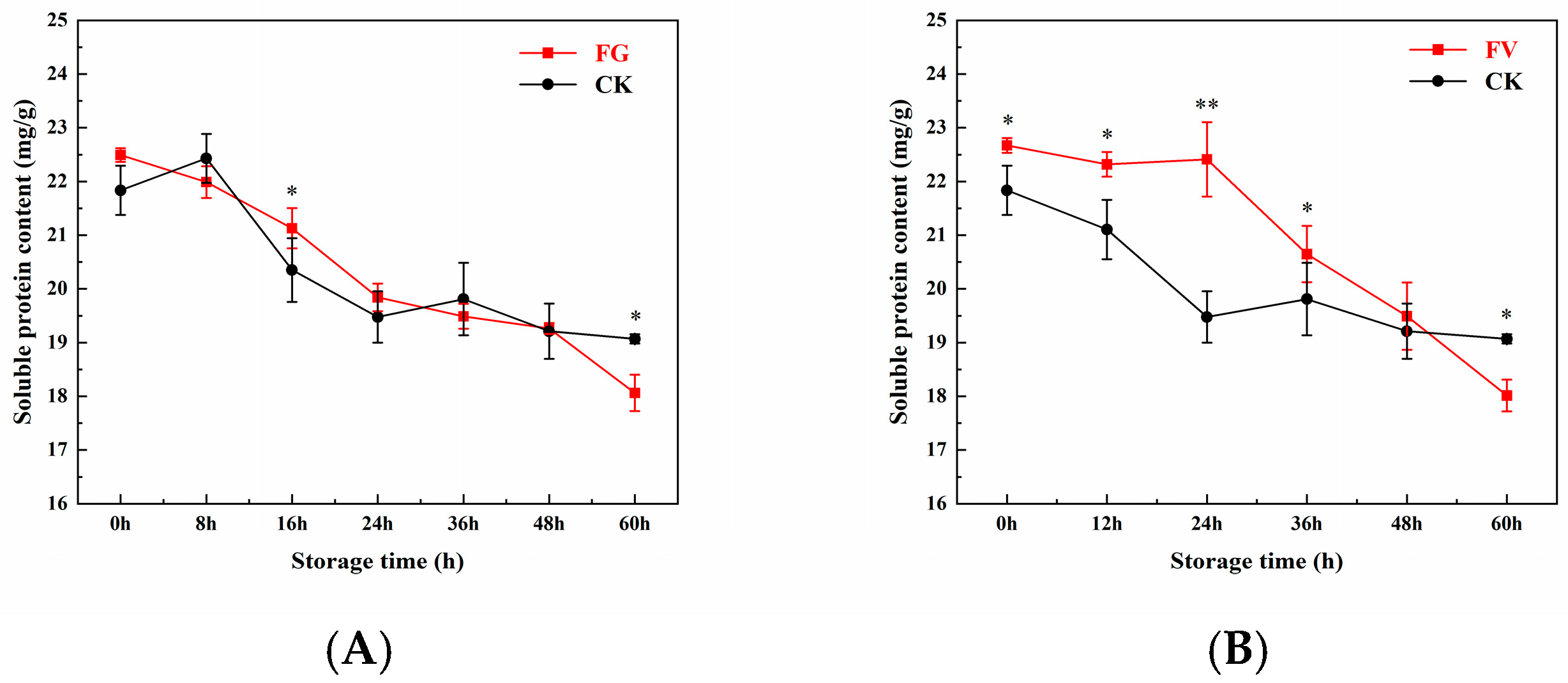

3.7. Changes in Soluble Protein Content of Sweet Corn

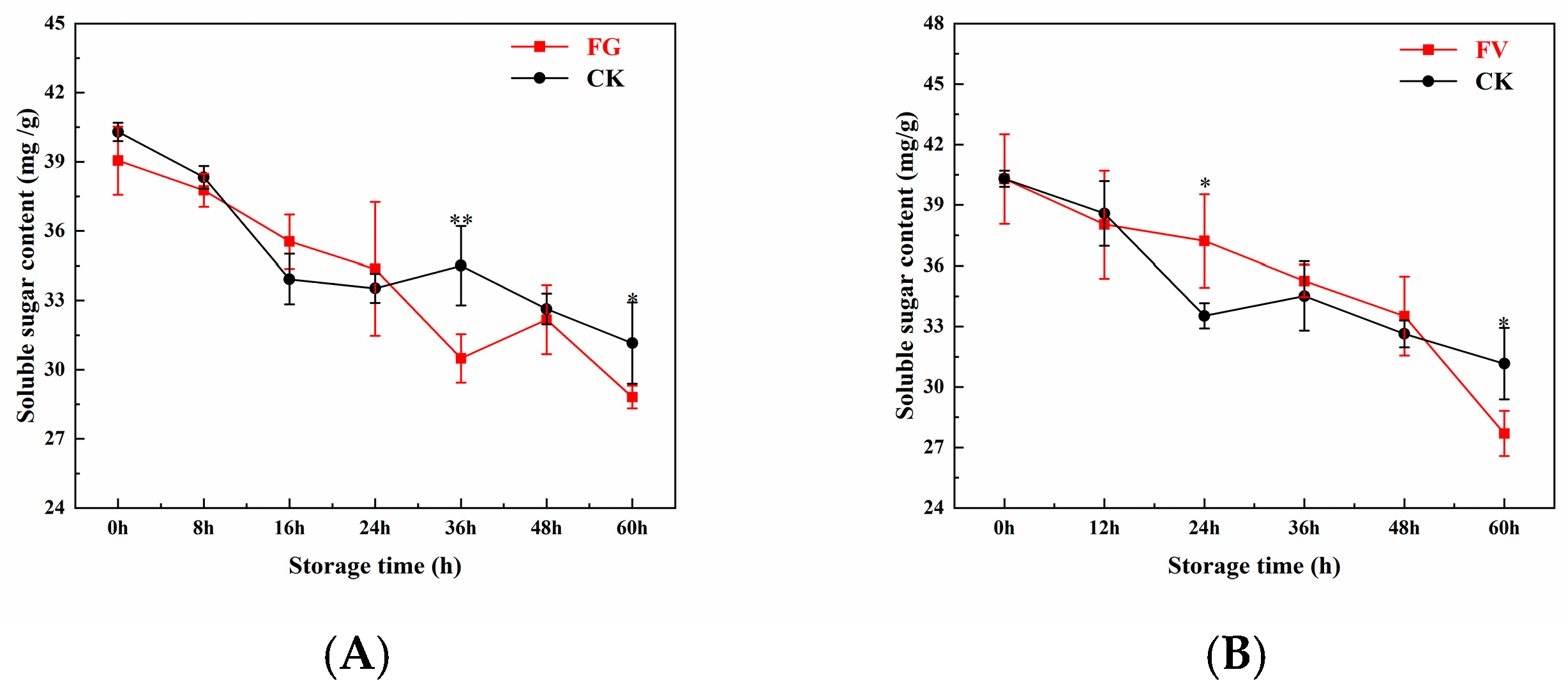

3.8. Changes in Soluble Sugar Content of Sweet Corn

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, L.; Jiang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Ju, T.; Jin, H.; Gao, C. Aged sweet corn (Zea mays L. saccharata Sturt) seeds trigger hormone and defense signaling during germination. J. Seed Sci. 2023, 45, e202345024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, M.; Zheng, N.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Li, L.; Gu, R.; Du, X.; Wang, J. Transcriptome analysis identifies novel genes associated with low-temperature seed germination in sweet corn. Plants 2022, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ma, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, R.; Shi, Y.; Watkins, C.B.; Zuo, J.; et al. Storage temperature affects metabolism of sweet corn. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zuo, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Bai, C.; Fernie, A.R.; Wang, R.; Shi, Y.; Tao, J.; Feng, X.; et al. Effects of low-voltage electrostatic field on post-harvest sugar metabolism and stress resistance in sweet corn. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2026, 231, 113859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, P.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Effects of different pre-cooling methods on the shelf life and quality of sweet corn (Zea mays L.). Plants 2023, 12, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, H.P.; Palanimuthu, V.; Srinivas, G. A study on shelf-life extension of sweet corn. Int. J. Food Ferment. Technol. 2017, 7, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yactayo, J.P.; Boehlein, S.; Beiriger, R.L.; Resende, M.F.R.; Bruton, R.G.; Alborn, H.T.; Romero, M.; Tracy, W.F.; Block, A.K. The impact of post-harvest storage on sweet corn aroma. Phytochem. Lett. 2022, 52, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xie, L.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, G. Impact of low temperature on the chemical profile of sweet corn kernels during post-harvest storage. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhong, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, B.; Luo, H.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, S.; Wang, S. Sensory evaluation and model prediction of vacuum-packed fresh corn during long-term storage. Foods 2023, 12, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, M.; Pierzgalski, A.; Zapaśnik, A.; Uwineza, P.A.; Ksieniewicz-Woźniak, E.; Modrzewska, M.; Waśkiewicz, A. Recent research on Fusarium mycotoxins in maize—A review. Foods 2022, 11, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Pedroso, I.R. Mycotoxins in cereal-based products and their impacts on the health of humans, livestock animals and pets. Toxins 2023, 15, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Shi, J.; Qiu, J.; Hou, Y.; Du, Y.; Gao, T.; Huang, W.; Wu, J.; Lee, Y.W.; Mohamed, S.R.; et al. Antifungal activities of a novel triazole fungicide, mefentrifluconazole, against the major maize pathogen Fusarium verticillioides. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 192, 105398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X. Physical resistance: A different perspective on maize ear rot resistance. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Abdallah, M.; De Boevre, M.; Landschoot, S.; De Saeger, S.; Haesaert, G.; Audenaert, K. Fungal endophytes control Fusarium graminearum and reduce trichothecenes and zearalenone in maize. Toxins 2018, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savignac, J.M.; Atanasova, V.; Chereau, S.; Ducos, C.; Gallegos, N.; Ortega, V.; Ponts, N.; Richard-Forget, F. Carotenoids occurring in maize affect the redox homeostasis of Fusarium graminearum and its production of type B trichothecene mycotoxins: New insights supporting their role in maize resistance to giberella ear rot. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 3285–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Shim, W.B. Vacuole proteins with optimized microtubule assembly is required for Fum1 protein localization and fumonisin biosynthesis in mycotoxigenic fungus Fusarium verticillioides. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josselin, L.; Proctor, R.H.; Lippolis, V.; Cervellieri, S.; Hoylaerts, J.; De Clerck, C.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Moretti, A. Does alteration of fumonisin production in Fusarium verticillioides lead to volatolome variation? Food Chem. 2024, 438, 138004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Geng, S.; Zhao, R.; Li, J.; Cao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J. FvOshC is a key global regulatory target in Fusarium verticillioides for fumonisin biosynthesis and disease control. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2024, 72, 15463–15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, D.; Ye, D.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Q.; Bai, H.; Meng, F. Biocontrol and mycotoxin mitigation: An endophytic fungus from maize exhibiting dual antagonism against Fusarium verticillioides and fumonisin reduction. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandicke, J.; De Visschere, K.; Croubels, S.; De Saeger, S.; Audenaert, K.; Haesaert, G. Mycotoxins in Flanders’ fields: Occurrence and correlations with Fusarium species in whole-plant harvested maize. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wu, C. Comparative acetylome analysis reveals the potential roles of lysine acetylation for DON biosynthesis in Fusarium graminearum. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.; Meng, D.; Zhang, W.; Jin, L.; Yi, X.; Dong, X.; Sun, M.; Chu, Y.; Duan, J. Mechanism insights into the enantioselective bioactivity and Fumonisin biosynthesis of mefentrifluconazole to Fusarium verticillioides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 9044–9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warth, B.; Preindl, K.; Manser, P.; Wick, P.; Marko, D.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T. Transfer and metabolism of the xenoestrogen zearalenone in human perfused placenta. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 107004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropejko, K.; Twarużek, M. Zearalenone and its metabolites-general overview, occurrence, and toxicity. Toxins 2021, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Liu, E.; Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Zhou, Z.; Yao, W.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H. Genetic variation in ZmWAX2 confers maize resistance to Fusarium verticillioides. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1812–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Hu, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D. Inhibition of fungal mycelial growth and mycotoxin production using ZnO@mSiO2 nanocomposite during maize storage. Food Biosci. 2025, 63, 105730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, R.; Shi, Y.; Cai, W.; Xu, T.; Wu, C.; Ma, L.; Bai, C.; Zhou, X.; et al. Chlorine dioxide affects metabolism of harvested sweet corn. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 211, 112834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Tian, Q.; Tao, X.; Luo, Z.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y. Nitrogen modified atmosphere packaging maintains the bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of postharvest fresh edible peanuts. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 190, 111957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, D.; Xu, W.; Fu, Y.; Liao, R.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y. Application of passive modified atmosphere packaging in the preservation of sweet corns at ambient temperature. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 136, 110295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, J.; Tan, L.; Wu, Q.; Lv, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Effects of zinc oxide nanocomposites on microorganism growth and protection of physicochemical quality during maize storage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 411, 110552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jia, S.; Xue, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Lv, H. Weissella cibaria DA2 cell-free supernatant improves the quality of sweet corn kernels during post-harvest storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 215, 113021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, P.; Gong, B.; Ding, S.; Shan, Y. Inhibitory mechanisms of cinnamic acid on the growth of Geotrichum citri-aurantii. Food Control 2022, 131, 108459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qu, J.; Feng, S.; Chen, T.; Yuan, M.; Huang, Y.; Liao, J.; Yang, R.; Ding, C. Seasonal variations in the chemical composition of liangshan olive leaves and their antioxidant and anticancer activities. Foods 2019, 8, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Hwang, K.T. Changes in physicochemical properties of mulberry fruits (Morus alba L.) during ripening. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 217, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Cui, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Qi, T.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Anti-mildew and fresh-keeping effect of Lactiplantibacillus paraplantarum P3 cell-free supernatant on fresh in-shell peanuts during storage process. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 418, 110719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; Pacheco, A.; Muñoz-Zavala, C.; Song, W.; Wang, H.; Cao, S.; Hu, G.; Zheng, H.; et al. Exploiting genomic tools for genetic dissection and improving the resistance to Fusarium stalk rot in tropical maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yi, W.; Liu, G.; Kang, N.; Ma, L.; Yang, G. Colour and chlorophyll level modelling in vacuum-precooled green beans during storage. J. Food Eng. 2021, 301, 110523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Brenes, P.; O´Hare, T. Effect of freezing and cool storage on carotenoid content and quality of zeaxanthin-biofortified and standard yellow sweet-corn (Zea mays L.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 86, 103353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jin, S.; Ding, Z.; Xie, J. Effects of different freezing methods on physicochemical properties of sweet corn during storage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, K.; Wang, X.; Sun, S.; Fang, J.; He, J.; Han, Q.; Zhao, G. Sodium alginate coating improves refrigerated sweet corn quality: Hormonal and metabolic responses. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 223, 113432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, D.D.; Akohoue, F.; Frank, S.; Koch, S.; Lieberherr, B.; Oyiga, B.; Kessel, B.; Presterl, T.; Miedaner, T. Comparison of four inoculation methods and three Fusarium species for phenotyping stalk rot resistance among 22 maize hybrids (Zea mays). Plant Pathol. 2024, 73, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakopoulos, D.; Luz, C.; Torrijos, R.; Meca, G.; Weber, P.; Bänziger, I.; Voegele, R.T.; Six, J.; Vogelgsang, S. Use of botanicals to suppress different stages of the life cycle of Fusarium graminearum. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Sanchez, F.; Taylor, G. Reducing post-harvest losses and improving quality in sweet corn (Zea mays L.): Challenges and solutions for less food waste and improved food security. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa Junior, O.F.; Dalcin, M.S.; Nascimento, V.L.; Haesbaert, F.M.; Ferreira, T.P.d.S.; Fidelis, R.R.; Sarmento, R.d.A.; Aguiar, R.W.d.S.; de Oliveira, E.E.; dos Santos, G.R. Fumonisin production by Fusarium verticillioides in maize genotypes cultivated in different environments. Toxins 2019, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yang, R.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, H.; Feng, F. Evaluation of biochemical and physiological changes in sweet corn seeds under natural aging and artificial accelerated aging. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yan, J.; Xie, J. Effect of vacuum and modified atmosphere packaging on moisture state, quality, and microbial communities of grouper (Epinephelus coioides) fillets during cold storage. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno, A.; Kägi, A.; Drakopoulos, D.; Bänziger, I.; Lehmann, E.; Forrer, H.R.; Keller, B.; Vogelgsang, S. From laboratory to the field: Biological control of Fusarium graminearum on infected maize crop residues. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Ren, X.; Du, Z.; Hou, J.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y.; An, Y. Fusarium mycotoxins: The major food contaminants. mLife 2024, 3, 176–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Kim, J.E.; Malapi-Wight, M.; Choi, Y.E.; Shaw, B.D.; Shim, W.B. Protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunits perform distinct functional roles in the maize pathogen Fusarium verticillioides. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachhadiya, S.; Kumar, N.; Seth, N. Process kinetics on physico-chemical and peroxidase activity for different blanching methods of sweet corn. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 4823–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Jia, L.J.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, D.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W. Cellular tracking and gene profiling of Fusarium graminearum during maize stalk rot disease development elucidates its strategies in confronting phosphorus limitation in the host apoplast. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaarschmidt, S.; Fauhl-Hassek, C. The fate of mycotoxins during secondary food processing of maize for human consumption. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 91–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Color | Storage Time | CK | FG |

|---|---|---|---|

| L* | 0 h | 69.80 ± 0.72 a | 69.42 ± 0.48 ab |

| 8 h | 69.78 ± 0.70 a | 68.76 ± 1.01 ab | |

| 16 h | 69.53 ± 0.93 ab | 69.78 ± 0.35 a | |

| 24 h | 70.32 ± 0.16 a | 66.47 ± 4.36 b | |

| 36 h | 69.87 ± 0.86 a | 68.99 ± 0.27 ab | |

| 48 h | 70.52 ± 0.78 a | 69.90 ± 0.41 a | |

| 60 h | 69.56 ± 1.15 ab | 70.16 ± 0.71 a | |

| b* | 0 h | 34.23 ± 2.11 abc | 33.20 ± 1.38 bcd |

| 8 h | 35.32 ± 0.57 a | 30.87 ± 0.86 ef | |

| 16 h | 34.46 ± 0.89 ab | 32.80 ± 0.69 bcd | |

| 24 h | 33.01 ± 0.51 bcd | 29.55 ± 2.24 fg | |

| 36 h | 31.54 ± 1.49 de | 28.82 ± 0.85 g | |

| 48 h | 32.68 ± 0.85 bcde | 29.31 ± 0.41 fg | |

| 60 h | 28.71 ± 0.98 g | 32.47 ± 1.04 cde |

| Color | Storage Time | CK | FV |

|---|---|---|---|

| L* | 0 h | 69.80 ± 0.72 ab | 68.05 ± 1.57 bc |

| 12 h | 70.36 ± 1.09 a | 68.62 ± 1.02 abc | |

| 24 h | 70.32 ± 0.16 a | 69.38 ± 0.82 ab | |

| 36 h | 69.87 ± 0.86 ab | 67.21 ± 1.17 c | |

| 48 h | 70.52 ± 0.78 a | 69.03 ± 0.68 abc | |

| 60 h | 69.56 ± 1.15 ab | 68.97 ± 1.81 abc | |

| b* | 0 h | 34.23 ± 2.11 a | 31.91 ± 2.75 abcd |

| 12 h | 33.13 ± 2.05 abc | 33.76 ± 0.73 ab | |

| 24 h | 33.01 ± 0.51 abc | 32.37 ± 0.90 abc | |

| 36 h | 31.54 ± 1.49 abcd | 29.70 ± 2.54 cd | |

| 48 h | 32.68 ± 0.85 abc | 30.26 ± 0.98 bcd | |

| 60 h | 28.71 ± 0.98 d | 29.59 ± 3.33 cd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, Y.; Liu, S.; Nie, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Lv, H. Effects of Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium verticillioides Infection on Sweet Corn Quality During Postharvest Storage. Foods 2025, 14, 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234147

Xue Y, Liu S, Nie Q, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Li Y, Lv H. Effects of Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium verticillioides Infection on Sweet Corn Quality During Postharvest Storage. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234147

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Yihan, Shaoyue Liu, Qianzi Nie, Xinru Zhang, Yan Zhao, Yanfei Li, and Haoxin Lv. 2025. "Effects of Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium verticillioides Infection on Sweet Corn Quality During Postharvest Storage" Foods 14, no. 23: 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234147

APA StyleXue, Y., Liu, S., Nie, Q., Zhang, X., Zhao, Y., Li, Y., & Lv, H. (2025). Effects of Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium verticillioides Infection on Sweet Corn Quality During Postharvest Storage. Foods, 14(23), 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234147