Bioeconomy and Climate Change: The Scenarios of Food Insecurity in Brazil’s Northern Region (Amazon) Due to the Shift from Traditional Table Crops to Globally Valued Commodities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of Study Area

2.2. Meteorological Data

2.3. Agricultural Production Data

2.4. Statistical Analyses

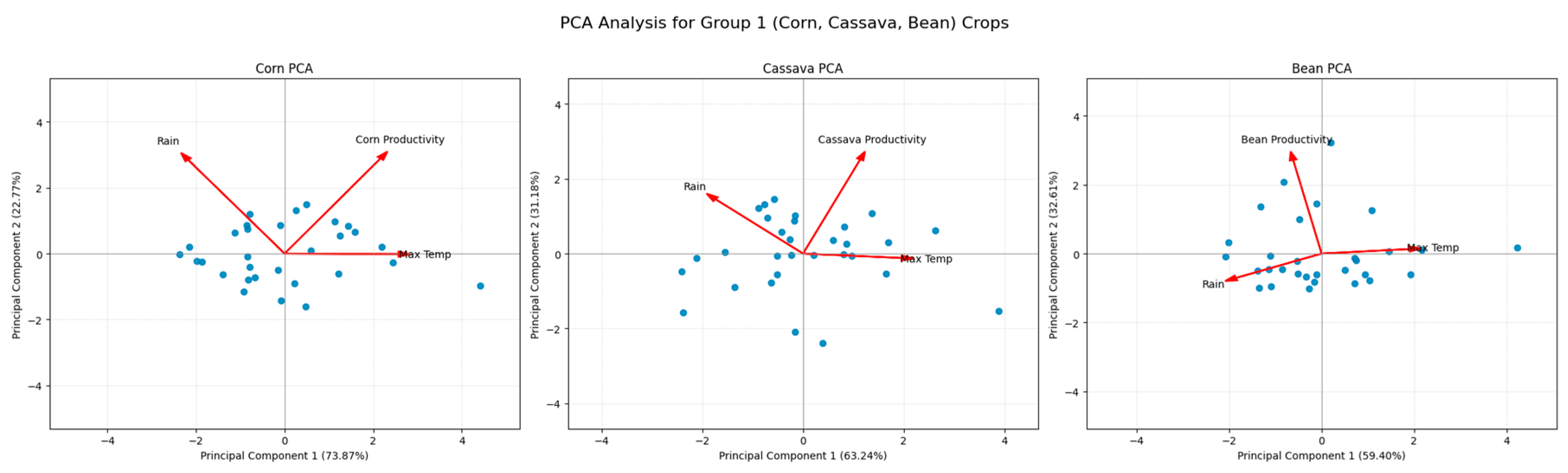

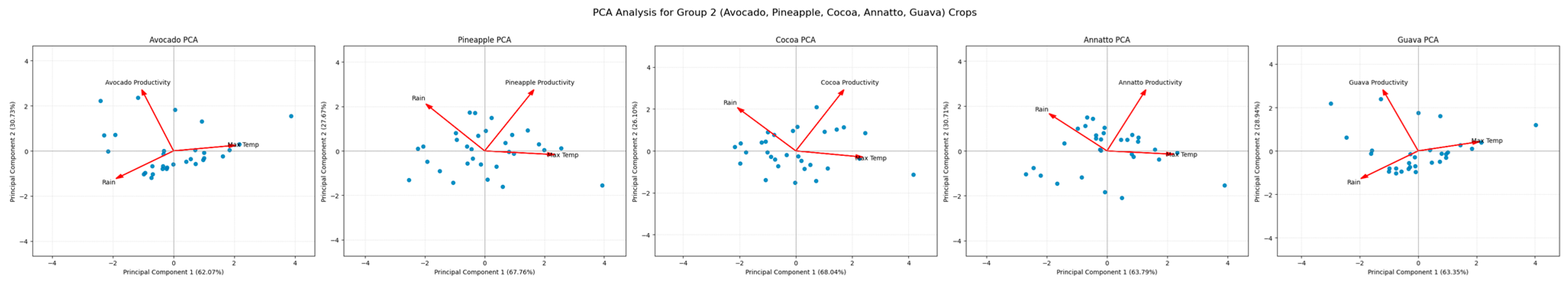

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture—Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2e90c833-8e84-46f2-a675-ea2d7afa4e24/content (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Arias, P.; Bellouin, N.; Coppola, E.; Jones, C.; Krinner, G.; Marotzke, J.; Naik, V.; Plattner, G.K.; Rojas, M.; Sillmann, J.; et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panelon Climate Change; Technical Summary; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Margulis, S. The Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Malhi, G.S.; Kaur, M.; Kaushik, P. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Its Mitigation Strategies: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G.R.; Lima, M.G.B. Understanding deforestation lock-in: Insights from Land Reform settlements in the Brazilian Amazon. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 951290. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwanger, J.H.; Kulmann-Leal, B.; Kaminski, V.L.; Valverde-Villegas, J.M.; da Veiga, A.B.G.; Spilki, F.R.; Fearnside, P.M.; Caesar, L.; Giatti, L.L.; Wallau, G.L.; et al. Beyond diversity loss and climate change: Impacts of Amazon deforestation on infectious diseasesand public health. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2020, 92, e20191375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.C.; Singer, B.H. Agricultural settlement and soil quality in the Brazilian Amazon. Popul. Environ. 2012, 34, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, Y.; Nobre, A.; Grace, J.; Kruijt, B.; Pereira, M.; Culf, A.; Scott, S. Carbon dioxide transfer over a Central Amazonian rain forest. J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103, 31593–31612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, F.E.; Costa, A.L.; Palheta, M.; Malhi, Y.; Meir, P.; Costa, J.D.P.; Ruivo, M.D.L.; Leal, L.D.S.; Costa, J.M.N.; Clement, R.J.; et al. Seasonality in CO2 and H2O flux at an eastern Amazonian rain forest. J. Geophys. Res. 2002, 107, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.C.; Nobre, A.D.; Kruijt, B.; Elbers, J.A.; Dallarosa, R.; Stefani, P.; Randow, C.; von Manzi, A.O.; Culf, A.D.; Gash, J.H.C.; et al. Comparative measurements of carbon dioxide fluxes from two nearby towers in a central Amazonian rainforest: The Manaus LBA site. J. Geophys. Res. 2002, 107, 8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.P.; da Silva, R.B.C.; Silva, C.M.S.e.; Bezerra, B.G.; Rego Mendes, K.; Marinho, L.A.; Barbosa, M.L.; Nunes, H.G.G.C.; Dos Santos, J.G.M.; Neves, T.T.d.A.T.; et al. Carbon and Energy Balance in a Primary Amazonian Forest and Its Relationship with Remote Sensing Estimates. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.A.; Guimarães, P.H.; Pereira, W.G.; Tamasauskas, L.D.; Gomes, M.S.; Corrêa, A.B.; Figueiredo, K.; Costa, G.; Costa, G.B.; Costa, F.A.; et al. Enhanced Carbon Flux Forecasting via STL Decomposition and Hybrid ARIMA-ES-LSTM Model in Amazon Forest. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 84713–84726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, K.R.; Marques, A.M.S.; Mutti, P.R.; Oliveira, P.E.S.; Rodrigues, D.T.; Costa, G.B.; Ferreira, R.R.; da Silva, A.C.N.; Morais, L.F.; Lima, J.R.S.; et al. Interannual Variability of Energy and CO2 Exchanges in a Remnant Area of the Caatinga Biome under Extreme Rainfall Conditions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, K.R.; Oliveira, P.E.; Lima, J.R.S.; Moura, M.S.; Souza, E.S.; Perez-Marin, A.M.; Cunha, J.E.B.; Mutti, P.R.; Costa, G.B.; de Sá, T.N.M.; et al. The Caatinga Dry Tropical Forest: A Highly Efficient Carbon Sink in South America. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 369, 110573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M.S.; Bezerra, B.; Mendes, K.; Mutti, P.; Rodrigues, D.; Costa, G.; De Oliveira, P.; Reis, J.; Marques, T.; Ferreira, R.; et al. Rainfall and rain pulse role on energy, water vapor and CO2 exchanges in a tropical semiarid environment. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 345, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.R.; Mendes, K.R.; Oliveira, P.E.S.; Mutti, P.R.; Moreira, D.S.; Antonino, A.C.D.; Menezes, R.S.C.; Lima, J.R.S.; Araújo, J.M.; Amorim, V.L.; et al. Simulating Energy Balance Dynamics to Support Sustainability in a Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest in Semi-Arid Northeast Brazil. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.F.D.; Moura, F.R.T.; Serufo, M.C.D.R.; Santos, W.P.D.; Costa, G.B.; Costa, F.A.R. The impact of meteorological changes on the quality of life regarding thermal comfort in the Amazon region. Front. Clim. 2023, 5, 1126042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germano, M.F.; Vitorino, M.I.; Cohen, J.C.P.; Costa, G.B.; Souto, J.I.O.; Rebelo, M.T.C.; Sousa, A.M.L. Analysis of the breeze circulations in eastern Amazon: An observational study. Atmos. Sci. Let. 2017, 18, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongor, J.E.; Owusu, M.; Oduro-Yeboah, C. Produção de cacau na década de 2020: Desafios e soluções. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2024, 5, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.L.; Siqueira Tavares Fernandes, G.; de Araujo Lima, E.; Almeida Lopes, J.R.; de Moura Neto, A.; de Oliveira Silva, R. Potential impacts of climate change on food crops in the state of Piauí, Brazil. Rev. Ceres 2025, 71, e71042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousky, V.E.; Kayano, M.T.; Cavalcanti, I.F.A. A review of the Southern Oscillation: Oceanic-atmospheric circulation changes and related rainfall anomalies. Tellus A 1984, 36, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.M.; Barros, V.R.; Doyle, M.E. Climate variability in southern South America associated with El Niño and La Niña events. J. Clim. 2000, 13, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Enso: Recent Evolution, Current Status and Predictions; Climate Pretiction Center: College Park, MD, USA, 2025.

- Li, K.; Zheng, F.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, J. Record-breaking global temperature and crises with strong El Niño in 2023–2024. Innov. Geosci. 2023, 1, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.C.; Pio, R.; Ramos, J.D.; Lima, L.C.O.; Pasqual, M.; Santos, V.A. Fenologia e Características Físico-Químicas de Frutos de abacateiros visando à Extração de Óleo. Ciência Rural 2013, 43, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbrocco, M. Comunidade que Sustenta a Agricultura (CSA): Na contramão do agronegócio globalizado. Bol. Campineiro Geogr. 2023, 12, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhiary, M.; Saha, D.; Kumar, R.; Sethi, L.N.; Kumar, A. Enhancing Precision Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of MachineLearning and AI Vision Applications in All-Terrain Vehicle for Farm Automation. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panotra, N.; Belagalla, N.; Mohanty, L.K.; Ramesha, N.M.; Gulaiya, S.; Yadav, K.; Pandey, S.K. Vertical farming: Addressing thechallenges of 21st century agriculture through innovation. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 664–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.B.; Neves, T.T.A.T.; Peres, L.V.; Andrade, A.M.D.; Silva, A.S.; Oliveira, P.A.; Santana, R.A.S.; Reis, I.M.S.; Sia, E.F.; Lara, T.S.; et al. Potencial de fortalecimento da bioeconomia e cadeias produtivas na região oeste do Pará através de produtos agrometeorológicos do Observatório Atmosférico da Amazônia (OBATMAM)—Fazenda Experimental da UFOPA. In Fazenda Experimental da Ufopa: Dez anos de Contribuição no Ensino, na Pesquisa e na Extensão, 1st ed.; Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará: Santarém, Brazil, 2025; pp. 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Abramovay, R. Uma Bioeconomia Inovadora para a Amazônia: Por uma Floresta em Pé e Rios Fluindo. In The Amazon Assessment Report 2021: The Amazon We Want; Lovejoy, T., Nobre, C., Barlow, J., Eds.; Science Panel for the Amazon (SPA): São Paulo, Brazil, 2021; pp. 1–32. Available online: https://www.theamazonwewant.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/SPA-Chapter-23-Portuguese.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Shennan-Farpón, Y.; Mills, M.; Souza, A.; Homewood, K. The role of agroforestry in restoring Brazil’s Atlantic Forest: Opportunities and challenges for smallholder farmers. People Nat. 2022, 4, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covey, K.; Soper, F.; Pangala, S.; Bernardino, A.; Pagliaro, Z.; Basso, L.; Cassol, H.; Fearnside, P.; Navarrete, D.; Novoa, S.; et al. Carbon and beyond: The biogeochemistry of climate in a rapidly changing Amazon. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 618401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.A.; Sampaio, G.; Borma, L.S.; Castilla-Rubio, J.C.; Silva, J.S.; Cardoso, M. Land-use and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of a novel sustainable development paradigm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10759–10768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, J.L.; Hegewisch, K.C.; Daudert, B.; Morton, C.G.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; McEvoy, D.J.; Erickson, T. Climate Engine: Cloud Computing for Big Climate Data. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 94, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEMAS–Secretaria de Estado de Meio Ambiente e Sustentabilidade do Pará. Plano Estadual de Bioeconomia do Pará—Planbio; Governo do Estado do Pará: Belém, Brazil, 2022. Available online: https://www.semas.pa.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Plano-Estadual-V9_pg-simple-2-1.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. Global Price of Cocoa [PCOCOUSDA]; FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2025; Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCOCOUSDA (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Selina Wamucii. Avocados Price in US—July 2025 Market Prices (Updated Daily); Selina Wamucii Insights: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- IMARC Group. Guavas Pricing Report 2024: Price Trend, Chart, Market Analysis, News, Demand, Historical and Forecast Data; IMARC Group: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/guavas-pricing-report/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Safras & Mercado. Safras Indica Cautela na Comercialização do Feijão e Busca por Novas Estratégias no Início de 2025; Safras & Mercado: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2025; Available online: https://safras.com.br/safras-indica-cautela-na-comercializacao-do-feijao-e-busca-por-novas-estrategias-no-inicio-de-2025/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Selina Wamucii. Pineapples Price in US—July 2025 Market Prices (Updated Daily); Selina Wamucii Insights: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025; Available online: https://www.selinawamucii.com/insights/prices/united-states-of-america/pineapples/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Selina Wamucii. Cassava Price in US—July 2025 Market Prices (Updated Daily); Selina Wamucii Insights: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025; Available online: https://www.selinawamucii.com/insights/prices/united-states-of-america/cassava/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Volza. Annatto Seed Export; Volza: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2025; Available online: https://www.volza.com/p/annatto-seed/export/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- IndexMundi. Corn Prices—30-Year Historical Data; IndexMundi: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.indexmundi.com/commodities/?commodity=corn&months=360 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- GGWeather. Weather Report and Meteorological Phenomena for 2021; GGWeather: Half Moon Bay, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.ggweather.com (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Raghuraman, S.P.; Soden, B.; Clement, A.; Vecchi, G.; Menemenlis, S.; Yang, W. The 2023 global warming spike was driven by the El Niño–Southern Oscillation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 11275–11283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.T.C.; Almada, N.B.; Matias, L.V.S.; Macambira, A.C.S.; Costa, G.B.; Sousa, J.T.R.; Heidemann, M.A. Caracterização Climatológica da Cidade de Manaus/AM. Biodivers. Bras.-BioBrasil 2021, 11, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, I.K.; Wollmann, J.B.; Gilson, I.A.; Silva, W.M. Produção e plantio do abacate e suas características na economia brasileira e mundial. Rev. Biodivers. 2023, 22, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Grüter, R.; Trachsel, T.; Laube, P.; Jaisli, I. Expected global suitability of coffee, cashew and avocado due to climate change. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, J.; Tezara, W.; Herrera, A. Physiological responses to drought and experimental water deficit and waterlogging offour clones of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) selected for cultivation in Venezuela. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 171, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igawa, T.K.; Toledo, P.M.; Anjos, L.J.S. Climate change could reduce and spatially reconfigure cocoa cultivation in the Brazilian Amazon by 2050. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, V.P.; Martin, D.G.; Giannini, T.C.; Silva Junior, R.; Guimarães, J.T.F.; Moia, G.C.M.; Silva, R.N.P. The cocoa bioeconomy in the eastern Amazon: An integrated analysis of production, environmental degradation perceptions and socioeconomic factors among farmers. Agric. Syst. 2025, 229, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.F. Cadernos do Semiárido Riquezas & Oportunidades; Conselho Regional de Engenharia e Agronomia de Pernambuco: Recife, Brazil, 2020; Volume 17, Número 3. Editora UFRPE; Available online: https://www.creape.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/CADERNO-SEMIARIDO-17-FEIJAO-CAUPI.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Maia, S.T.; Costa, T.V.; Costa, F.S. Níveis tecnológicos na produção de abacaxi (Ananas comosus) em agroecossistemas familiares de Novo Remanso (Itacoatiara/Amazonas). Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2024, 62, e269860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarante, C.V.T.; Steffens, C.; Ducroquet, J.P.; Sasso, A. Qualidade de goiaba-serrana em resposta à temperatura de armazenamento e ao tratamento com 1-metilciclopropeno. Pesq. Agropecu. Bras. 2008, 43, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanure, T.M.P.; Miyajima, D.N.; Magalhães, A.S.; Domingues, E.P.; Carvalho, T.S. The Impacts of Climate Change on Agricultural Production, Land Use and Economy of the Legal Amazon Region Between 2030 and 2049. EconomiA 2020, 21, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fritz, S.; van Wesenbeeck, C.F.A.; Fuchs, M.; You, L.; Obersteiner, M.; Yang, H. A spatially explicit assessment of current and future hotspots of hunger in sub-Saharan Africa in the context of global change. Glob. Planet. Change 2008, 64, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Burke, M.B.; Tebaldi, C.; Matrandrea, M.D.; Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, L.R. Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science 2008, 319, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenker, W.; Lobell, D.B. Robust negative impacts of climate change on African agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 014010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, A.; Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Campo, B.V.H.; Navarro-Racines, C. Is cassava the answer to African climate change adaptation? Trop. Plant Biol. 2012, 5, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pìnheiro, C.P.S.; Silva, L.C.; Matlaba, V.J.; Giannini, T.C. Agribusiness and environmental conservation in tropical forests in the eastern Amazon. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, E.S.; Azevedo-Ramos, C.; Carneiro Guedes, M.C. Segurança alimentar de famílias extrativistas de açaí na Amazônia oriental brasileira: O caso da Ilha das Cinzas (Food security of açai extractivist families in the Brazilian eastern Amazon: The case of Ilha das Cinzas). Novos Cad. NAEA 2021, 24, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, G.H.; Molina, S.M.G. Ocupação Humana e Transformação das Paisagens na Amazônia Brasileira. Amaz.-Rev. Antropol. 2009, 1, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha Sousa Filho, H.; de Almeida Bezerra, M.; Mota de Jesus, R.; Chiapetti, J. Cocoa Production and Distribution in Bahia (Brazil) after the Witch’s Broom. In Shifting Frontiers of Theobroma Cacao—Opportunities and Challenges for Production; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, O.P.; Teodoro, R.E.F.; Melo, B.; Torres, J.L.R. Qualidade do fruto e produtividade do abacaxizeiro em diferentes densidades de plantio e lâminas de irrigação. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2009, 44, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.R.A.; Sanches, A.L.R.; Barros, G.S.C. A nova configuração no mercado de milho no Brasil e a dinâmica de formação de preços. Agroalimentaria 2019, 25, 65–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sanches, A.L.R.; Alves, L.R.A.; Barros, G.S.C.; Osaki, M. Os impactos dos preços do milho ao longo das cadeias consumidoras. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2024, 62, e274483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, G.; Läderach, P.; Martinez-Valle, A.I.; Bunn, C.; Jassogne, L. Vulnerability to Climate Change of Cocoa in West Africa: Patterns, Opportunities and Limits to Adaptation. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 556, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, A.M.; dos Reis Neto, J.F.; Soares, D.G.; Heredia-Vieira, S.C. A Influência das Condições Edafoclimáticas para Produção de Urucum (Bixa orellana) no Cerrado Sul-Mato-Grossense. Ens. Ciência: Ciências Biológicas Agrárias Saúde 2024, 28, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, A.; Prabhakara, P.G.; Rao, D.G. Chemistry, processing and toxicology of annatto (Bixa orellana L.). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 40, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lorençone, J.A.; Lorençone, P.A.; Lima, R.F.; Torsoni, G.B.; Aparecido, L.E.O. Alterações no Zoneamento Climático para o Cultivo de Urucum (Bixa orellana) Devido às Mudanças Climáticas. In Anais do 19º Congresso Nacional de Meio Ambiente de Poços de Caldas; IFSULDEMINAS: Poços de Caldas, Brazil, 2022; Volume 19, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Poltronieri, M.C.; Botelho, S.M. Current Situation and Potential of Annatto (Bixa orellana L.) Cultivation in the Northern Region of Brazil. In Proceedings of the SIMBRAU—Brazilian Symposium on Annatto, João Pessoa, Brazil, 17 April 2006. Lectures, Available on CD-ROM. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, P.; Warang, O.; Das, S.; Das, S. Impact of Climate Change on Fruit Crops-a Review. Curr. World Environ. 2022, 17, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, L.F.A.; de Paulo, S.R.; de Paulo, I.J.C.; de Oliveira Maionchi, D.; da Silva, H.J.A.; de Oliveira Costa, R.; da Silva, I.M.C.B.; Marques, J.B.; de Souza Lima, A.M.; Rodrigues, T.R. Trends and Patterns of Daily Maximum, Minimum and Mean Temperature in Brazil from 2000 to 2020. Climate 2023, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.R.G.M.; Duarte, V.N.; Staduto, J.A.R.; Kreter, A.C. Land-Use Dynamics for Agricultural and Livestock in Central-West Brazil and Its Reflects on the Agricultural Frontier Expansion. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2023, 4, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.N.; Castro, C.N. Expansão da produção agrícola, novas tecnologias de produção, aumento de produtividade e o desnível tecnológico no meio rural. Texto Para Discussão (IPEA) 2022, 2765, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, M.A.B.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Albernaz, A.L.K.M.; Magalhães, J.L.L.; Lees, A.C. Floristic impoverishment of Amazonian floodplain forests managed for açaí fruit production. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 351, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Gutiérrez, I.; Manners, R.; Varela-Ortega, C.; Tarquis, A.M.; Martorano, L.G.; Toledo, M. Examining the sustainability and development challenge in agricultural-forest frontiers of the Amazon Basin through the eyes of locals. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, E.C.G.; Silva, T.C.; da Cunha Neto, E.M.; Favarin, J.A.S.; da Silva Gomes, J.K.; das Chagas, K.P.T.; Fiorelli, E.C.; Sonsin, A.F.; Maia, E. Bioeconomy in the Amazon: Lessons and gaps from thirty years of non-timber forest products research. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, W.; Lara, T.; Andrade, A.; Seruffo, M.; Andrade, A.; Silva, C.; Bezerra, B.; Mendes, K.; Reis, I.; Santos, I.; et al. Bioeconomy and Climate Change: The Scenarios of Food Insecurity in Brazil’s Northern Region (Amazon) Due to the Shift from Traditional Table Crops to Globally Valued Commodities. Foods 2025, 14, 4146. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234146

Pereira W, Lara T, Andrade A, Seruffo M, Andrade A, Silva C, Bezerra B, Mendes K, Reis I, Santos I, et al. Bioeconomy and Climate Change: The Scenarios of Food Insecurity in Brazil’s Northern Region (Amazon) Due to the Shift from Traditional Table Crops to Globally Valued Commodities. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4146. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234146

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Waldeir, Tulio Lara, Antônio Andrade, Marcos Seruffo, Aurilene Andrade, Cláudio Silva, Bergson Bezerra, Keila Mendes, Iolanda Reis, Iracenir Santos, and et al. 2025. "Bioeconomy and Climate Change: The Scenarios of Food Insecurity in Brazil’s Northern Region (Amazon) Due to the Shift from Traditional Table Crops to Globally Valued Commodities" Foods 14, no. 23: 4146. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234146

APA StylePereira, W., Lara, T., Andrade, A., Seruffo, M., Andrade, A., Silva, C., Bezerra, B., Mendes, K., Reis, I., Santos, I., Marinho, L., Nunes, H., Barros, J., Lima, M., Silva, L., Monteiro, R., Santos, J., Neves, T., Santana, R., ... Brito-Costa, G. (2025). Bioeconomy and Climate Change: The Scenarios of Food Insecurity in Brazil’s Northern Region (Amazon) Due to the Shift from Traditional Table Crops to Globally Valued Commodities. Foods, 14(23), 4146. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234146