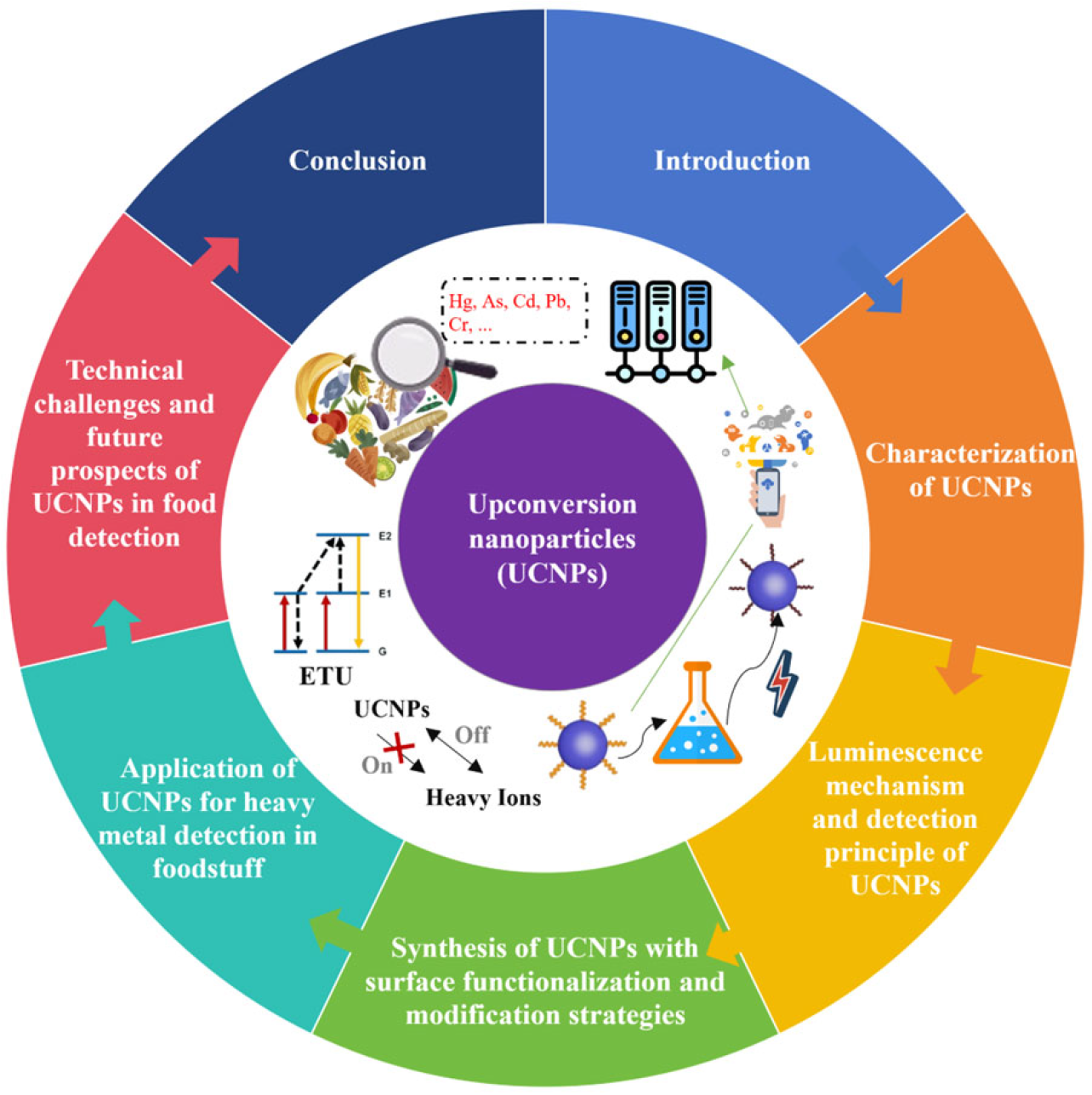

Research Progress on the Application of Upconversion Nanoparticles in Heavy Metal Detection in Foodstuff

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characterization of UCNPs and Their Advantages in the Detection of Heavy Metals

2.1. Characterization of UCNPs

2.2. Advantages of UCNPs for the Detection of Heavy Metals in Foodstuff

3. Luminescence Mechanism of UCNPs and Its Detection Principle

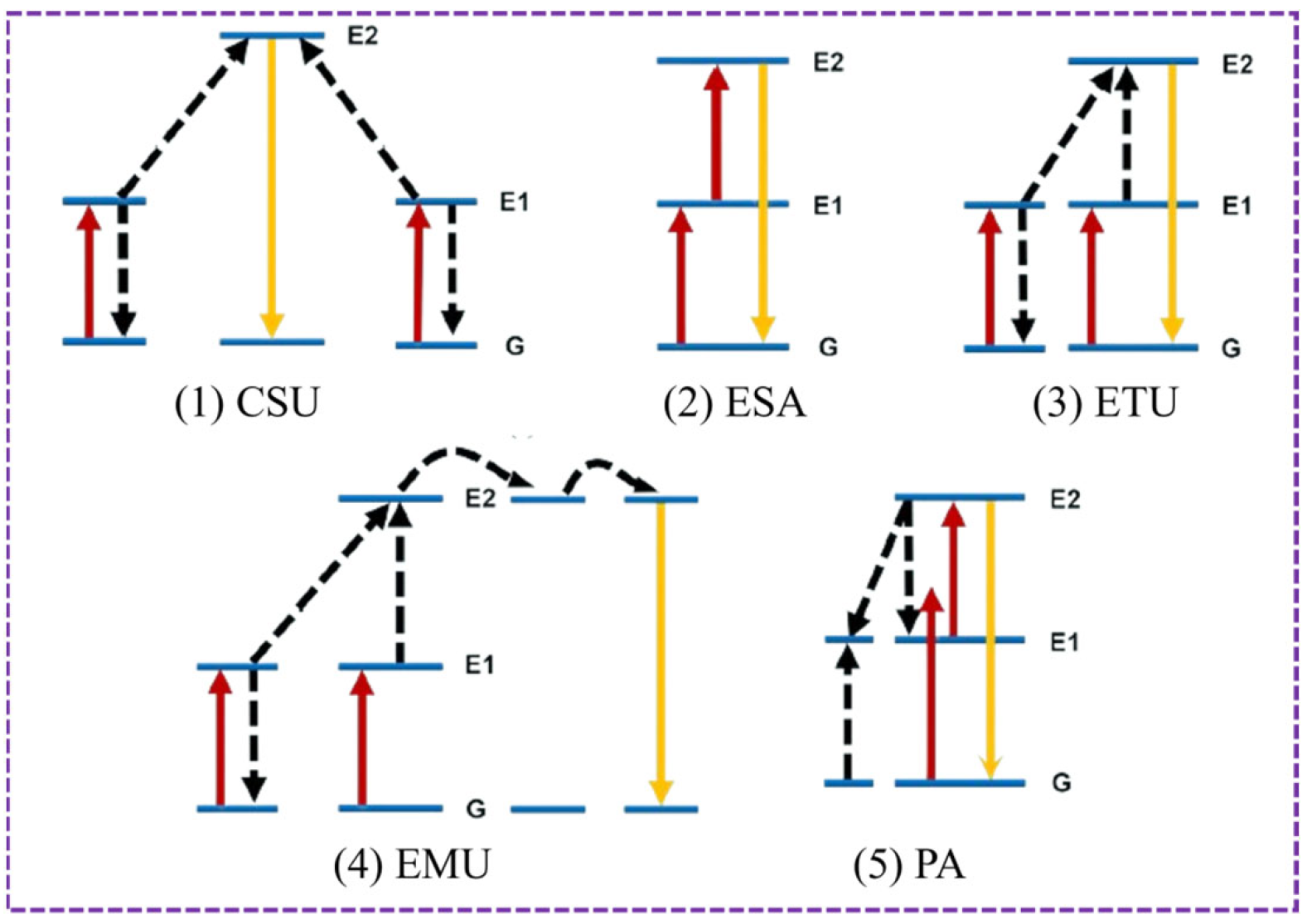

3.1. Luminescence Mechanism of UCNPs

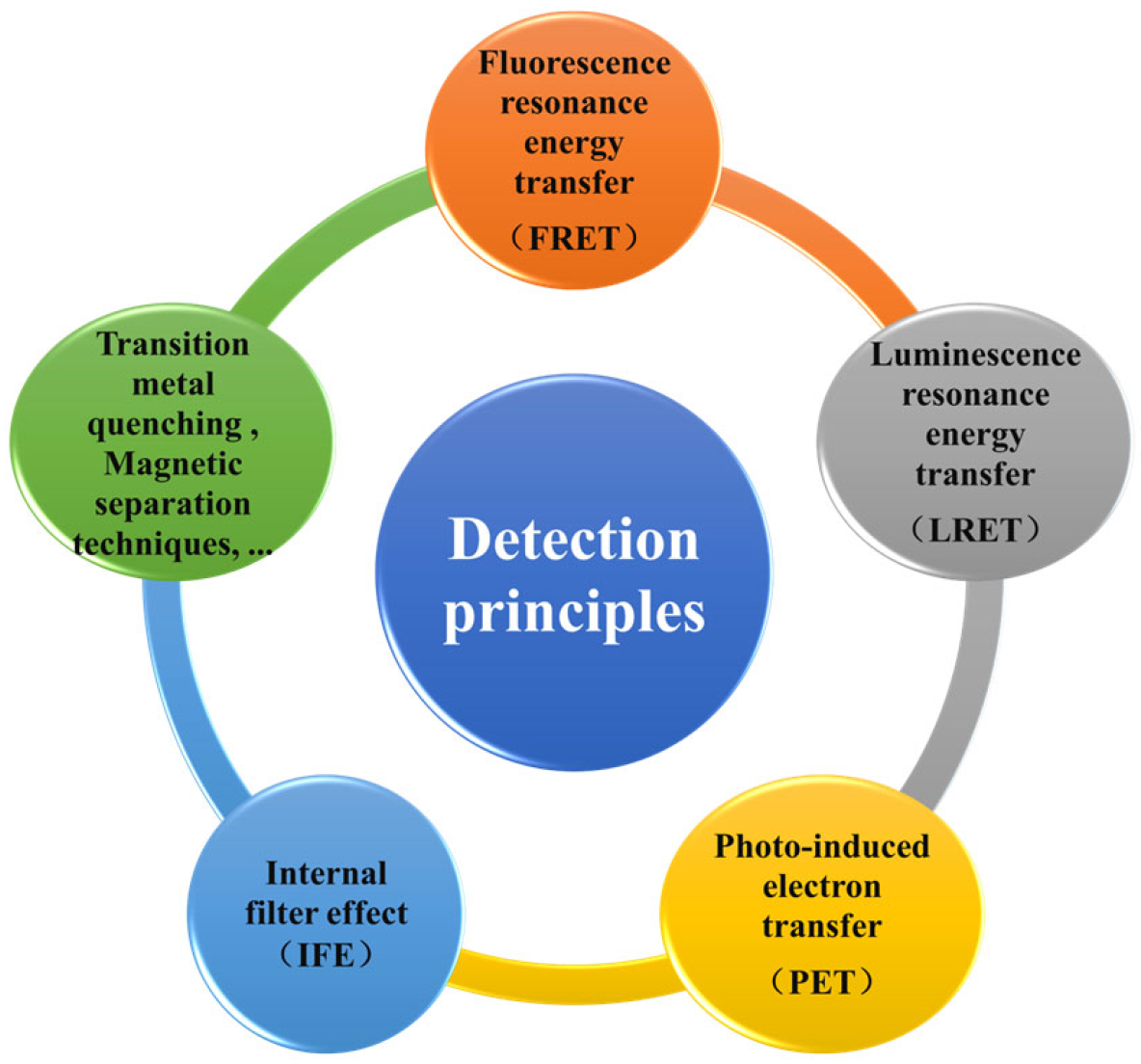

3.2. Detection Principle of UCNPs in Food Heavy Metals

4. Synthesis of UCNPs with Surface Functionalization and Modification Strategies

4.1. Synthesis of UCNPs

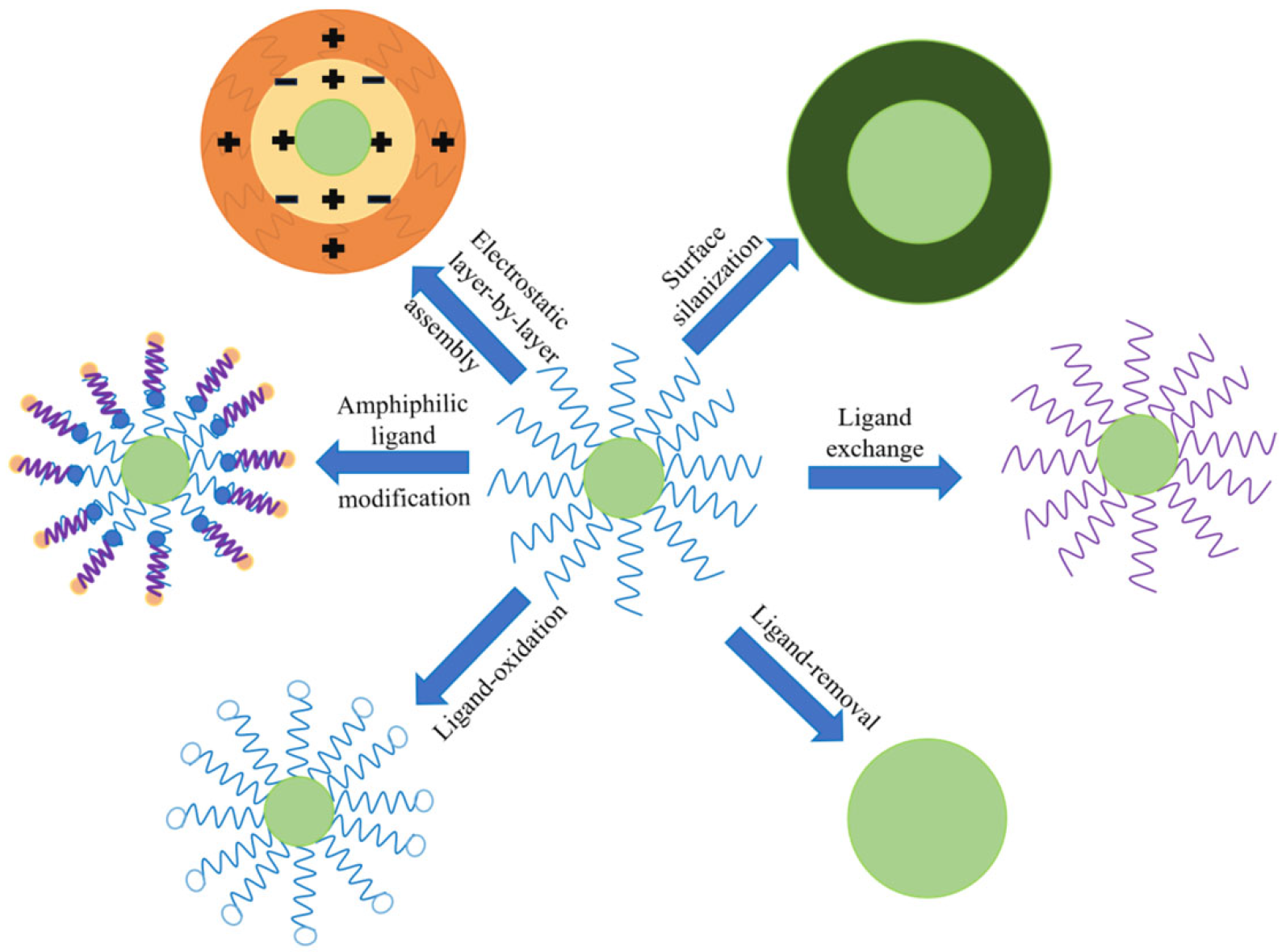

4.2. Surface Functionalization Modification Strategies for UCNPs

5. Sample Pretreatment

6. Application of UCNPs for Heavy Metal Detection in Foodstuff

6.1. Detection of Mercury Ions

6.2. Detection of Arsenic Ions

6.3. Detection of Cadmium Ions

6.4. Detection of Lead Ions

6.5. Detection of Other Common Trace Metal Ions

7. Technical Challenges and Future Prospects of UCNPs in Food Detection

7.1. Current Challenges

7.2. Future Prospects

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UCNPs | Upconversion Nanoparticles |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| MOF | Metal–Organic Framework |

| CSU | Cooperative Sensitization Upconversion |

| ESA | Excited State Absorption |

| ETU | Energy Transfer Upconversion |

| EMU | Energy Migration-mediated Upconversion |

| PA | Photon Avalanche |

| FRET | Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer |

| LRET | Luminescence Resonance Energy Transfer |

| PET | Photo-induced Electron Transfer |

| IFE | Internal Filter Effect |

| AuNPs | Au Nanoparticles |

| HOMO | Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital |

| LUMO | Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital |

| UCL | Upconversion Luminescence |

| ICT | Intra-molecular Charge Transfer |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CAC | Codex Alimentarius Commission |

| MRS | Magnetic Relaxation Switch |

| HRP | Horseradish Peroxidase |

| TMB | Tetramethylbenzidine |

| EU | European Union |

| BHQ | Black Hole Quencher |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

| ECL | Electrochemical Luminescence |

| RET | Resonance Energy Transfer |

| BN | Boron Nitride |

| QD | Quantum Dot |

| PAA | Poly(Acrylic Acid) |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| LFA | Lateral Flow Assay |

| AgNCs | Ag Nanoclusters |

References

- Nowicka, B. Heavy metal–induced stress in eukaryotic algae-mechanisms of heavy metal toxicity and tolerance with particular emphasis on oxidative stress in exposed cells and the role of antioxidant response. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 16860–16911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xu, L.; Buyong, F.; Chay, T.C.; Li, Z.; Cai, Y.; Hu, B.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X. Modified biochar: Synthesis and mechanism for removal of environmental heavy metals. Carbon Res. 2022, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Vashishth, R. From water to plate: Reviewing the bioaccumulation of heavy metals in fish and unraveling human health risks in the food chain. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 10, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: Soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.M.; Zakeel, M.C.M.; Zavahir, J.S.; Marikar, F.M.; Jahan, I. Heavy metal accumulation in rice and aquatic plants used as human food: A general review. Toxics 2021, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerma, M.; Cantu, J.; Banu, K.S.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Environmental assessment in fine jewelry in the US-Mexico’s Paso del Norte region: A qualitative study via X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 161004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Devi, I. Animal waste as a valuable biosorbent in the removal of heavy metals from aquatic ecosystem—An eco-friendly approach. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Yuan, H.; Liu, B.; Peng, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, D. Review of the distribution and detection methods of heavy metals in the environment. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 5747–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xie, X.; Meng, T.; Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Jin, H.; Jin, C.; Meng, X.; Pang, H. Recent advance of nanomaterials modified electrochemical sensors in the detection of heavy metal ions in food and water. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kong, L.; Zhou, S.; Ma, C.; Lin, W.; Sun, X.; Kirsanov, D.; Legin, A.; Wan, H.; Wang, P. Development of QDs-based nanosensors for heavy metal detection: A review on transducer principles and in-situ detection. Talanta 2022, 239, 122903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sheng, W.; Haruna, S.A.; Hassan, M.M.; Chen, Q. Recent advances in rare earth iondoped upconversion nanomaterials: From design to their applications in food safety analysis. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 3732–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Hakeem, D.; Su, S.; Mo, Z.; Wen, H. Upconversion luminescent nanomaterials: A promising new platform for food safety analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022, 62, 8866–8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, F. Bioapplications and biotechnologies of upconversion nanoparticle-based nanosensors. Analyst 2016, 141, 3601–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Bednarkiewicz, A.; Falk, A.; Fröhlich, E.; Lisjak, D.; Prina-Mello, A.; Resch, S.; Schimpel, C.; Vrček, I.V.; Wysokińska, E.; et al. Critical considerations on the clinical translation of upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs): Recommendations from the European upconversion network (COST Action CM1403). Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1801233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, E.S.; Joud, F.; Wiesholler, L.M.; Hirsch, T.; Hall, E.A. Upconversion nanoparticles as intracellular pH messengers. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 6567–6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegemann, J.; Augustin, M.N.; Ackermann, J.; Fizzi, N.E.H.; Neutsch, K.; Gregor, M.; Herbertz, S.; Kruss, S. Levodopa sensing with a nanosensor array via a low-cost near infrared readout. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 13655–13662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Pendharkar, A.I.; Lu, M.; Huang, L.; Huang, W.; Han, G. Emerging≈ 800 nm excited lanthanidedoped upconversion nanoparticles. Small 2017, 13, 1602843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, K.; Hrovat, D.; Kumar, B.; Qu, G.; Houten, J.V.; Ahmed, R.; Piunno, P.A.E.; Gunning, P.T.; Krull, U.J. Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles: Exploring a treasure trove of NIR-mediated emerging applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 2499–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q. Upconversion nanoparticles based sensing: From design to point-of-care testing. Small 2024, 20, 2311729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Liu, L.; Bai, L.; Xia, C.; Gao, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, B. Control synthesis, subtle surface modification of rare-earth-doped upconversion nanoparticles and their applications in cancer diagnosis and treatment. Mat. Sci Eng. C-Mater. 2019, 105, 110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Han, L.; Ma, H.; Lan, W.; Tu, K.; Peng, J.; Su, J.; Pan, L. An aptamer sensor based on alendronic acid-modified upconversion nanoparticles combined with magnetic separation for rapid and sensitive detection of thiamethoxam. Foods 2025, 14, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giust, D.; Lucío, M.I.; El-Sagheer, A.H.; Brown, T.; Williams, L.E.; Muskens, O.L.; Kanaras, A.G. Graphene oxide–upconversion nanoparticle based portable sensors for assessing nutritional deficiencies in crops. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6273–6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Wu, X.; Sun, M.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, A.; Xu, L.; Xu, C.; Kuang, H. Chiral core–shell upconversion nanoparticle@MOF nanoassemblies for quantification and bioimaging of reactive oxygen species in vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 19373–19378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, A.; Wu, X.; Li, S.; Sun, M.; Xu, L.; Kuang, H.; Xu, C. An NIR-responsive DNA-mediated nanotetrahedron enhances the clearance of senescent cells. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2000184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Lin, G.; Clarke, C.; Zhou, J.; Jin, D. Optical nanomaterials and enabling technologies for high-security-level anticounterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1901430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Liu, X.; Lv, Y.; Lu, G.H.; Li, F.; Zhang, F.; Liu, B.; Li, D.; Wei, W.; Li, Y. Nanolongan with multiple on-demand conversions for ferroptosis–apoptosis combined anticancer therapy. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Yao, J.; Zheng, F.; Peng, H.; Jiang, S.; Yao, C.; Du, H.; Jiang, B.; Stanciu, S.G.; Wu, A. Guarding food safety with conventional and up-conversion near-infrared fluorescent sensors. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 41, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.; Islam, F.; Prinz, C.; Gehrmann, P.; Licha, K.; Roik, J.; Recknagel, S.; Resch-Genger, U. Assessing the reproducibility and up-scaling of the synthesis of Er,Yb-doped NaYF4-based upconverting nanoparticles and control of size, morphology, and optical properties. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Gong, H.; Yang, D.; Feng, L.; Gai, S.; Zhang, F.; Ding, H.; He, F.; Yang, P. Research progress on rare earth up-conversion and near-infrared II luminescence in biological applications. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, N.; Chandra, S. Upconversion nanoparticles: Recent strategies and mechanism based applications. J. Rare Earth 2022, 40, 1343–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yan, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, B. Controlling upconversion in emerging multilayer core–shell nanostructures: From fundamentals to frontier applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 1729–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Upconversion nanoparticle-based fluorescence resonance energy transfer sensing platform for the detection of cathepsin B activity in vitro and in vivo. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefe, C.; Mehlenbacher, R.D.; Peng, C.S.; Zhang, Y.; Fischer, S.; Lay, A.; McLellan, C.A.; Alivisatos, A.P.; Chu, S.; Dionne, J.A. Sub-20 nm core–shell–shell nanoparticles for bright upconversion and enhanced förster resonant energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 16997–17005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Li, B.; Wu, Y.; He, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, H.; Dou, C.; Feng, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, F. A tumor-microenvironment-responsive lanthanide-cyanine FRET sensor for NIR-II luminescence-lifetime in situ imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2001172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ouyang, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q. Turn-on fluoresence sensor for Hg2+ in food based on FRET between aptamers-functionalized upconversion nanoparticles and gold nanoparticles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6188–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotulska, A.M.; Pilch-Wróbel, A.; Lahtinen, S.; Soukka, T.; Bednarkiewicz, A. Upconversion FRET quantitation: The role of donor photoexcitation mode and compositional architecture on the decay and intensity based responses. Light-Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Shao, M.; Jing, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, L. The emission quenching of upconversion nanoparticles coated with amorphous silica by fluorescence resonance energy transfer: A mercury-sensing nanosensor excited by near-infrared radiation. Spectrochim. Acta A 2021, 254, 119608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Jin, J.; Hu, L.; Hu, B.; Wang, M.; Guo, L.; Lv, X. Core-shell-shell upconversion nanomaterials applying for simultaneous immunofluorescent detection of fenpropathrin and procymidone. Foods 2023, 12, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, A.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S. Glutathione regulation-based dual-functional upconversion sensing-platform for acetylcholinesterase activity and cadmium ions. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, S.H.; Im, S.G.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, C.H.; Son, S.J.; Oh, H.B. Upconversion nanoparticle-based förster resonance energy transfer for detecting DNA methylation. Sensors 2016, 16, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Ma, Q.; Yu, W.; Dong, X.; Hong, X. “Off-On” typed upconversion fluorescence resonance energy transfer probe for the determination of Cu2+ in tap water. Spectrochim. Acta A 2022, 271, 120920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Zhang, C.; Fang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wu, F.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Detection of phospholipase A2 in serum based on LRET mechanism between upconversion nanoparticles and SYBR green I. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1143, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yu, C.; Han, L.; Shen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Yao, X.; Wu, F.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; et al. Upconversion luminescence–based aptasensor for the detection of thyroid-stimulating hormone in serum. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, W.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Cao, W.; Tong, L.; Tang, B. Luminescence-resonance-energy-transfer-based luminescence nanoprobe for in situ imaging of CD36 activation and CD36–oxLDL binding in atherogenesis. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 9770–9776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Bao, L.; Ding, L.; Ju, H. A single excitation-duplexed imaging strategy for profiling cell surface protein-specific glycoforms. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2016, 55, 5220–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hassan, M.M.; Rong, Y.; Liu, R.; Li, H.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. A solid-phase capture probe based on upconvertion nanoparticles and inner filter effect for the determination of ampicillin in food. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Fang, A.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S. Enzymatic-induced upconversion photoinduced electron transfer for sensing tyrosine in human serum. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 77, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Sun, B.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Qin, L.; Jiang, H. Highly efficient dual-mode detection of AFB1 based on the inner filter effect: Donor-acceptor selection and application. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1298, 342384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Tao, S.; Mo, J.; Chen, P.; Xiao, H.; Qi, H. Cellulose-based fluorescent chemosensor with controllable sensitivity for Fe3+ detection. Carbohyd. Polym. 2024, 346, 122620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Arora, A.; Mehta, N.; Kataria, R.; Mehta, S.K. Au nanoparticles decorated graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets as a sensitive and selective fluorescence probe for Fe3+ and dichromate ions in aqueous medium. Chemosphere 2024, 363, 142834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; Li, N.; Wei, J. Fabrication of multicolor Janus microbeads based on photonic crystals and upconversion nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2021, 592, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nampi, P.P.; Vakurov, A.; Saha, S.; Jose, G.; Millner, P.A. Surface modified hexagonal upconversion nanoparticles for the development of competitive assay for biodetection. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 136, 212763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Zong, L. Size-tunable β-NaYF4: Yb/Er up-converting nanoparticles with a strong green emission synthesized by thermal decomposition. Opt. Mater. 2020, 108, 110144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xu, J.; Zhu, K.; Yan, M.; He, M.; Huang, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, S.; Zeng, Q. A general synthesis method for small-size and water-soluble NaYF4: Yb, Ln upconversion nanoparticles at high temperature. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 38689–38696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegze, B.; Tolnai, G.; Albert, E.; Hessz, D.; Kubinyi, M.; Madarász, J.; May, Z.; Olasz, D.; Sáfrán, G.; Hórvölgyi, Z. Optimizing the composition of LaF3: Yb, Tm upconverting nanoparticles synthesised by the co-precipitation method to improve the emission intensity. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 21554–21560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetiker, N.; León, J.J.; Swihart, M.; Chen, K.; Pfeifer, B.A.; Dutta, A.; Pliss, A.; Kuzmin, A.N.; Pérez-Donoso, J.M.; Prasad, P.N. Unlocking nature’s brilliance: Using Antarctic extremophile Shewanella baltica to biosynthesize lanthanide-containing nanoparticles with optical up-conversion. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Xie, S.; Song, Y.; Tan, H.; Xu, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, L. Synthesis of lanthanide-ion-doped NaYF4 RGB up-conversion nanoparticles for anti-counterfeiting application. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 8207–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, H.; Guan, D.; Wen, R.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q. Effect of surface modification on the luminescence of individual upconversion nanoparticles. Small 2024, 20, 2309035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, X.; Li, X. Solvothermal synthesis and modification of NaYF4: Yb/Er@NaLuF4: Yb for enhanced up-conversion luminescence for bioimaging. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 42163–42171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Gong, L.; Dong, X.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gu, Z. Mass production of poly (ethylene glycol) monooleate-modified core-shell structured upconversion nanoparticles for bio-imaging and photodynamic therapy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlaváček, A.; Farka, Z.; Mickert, M.J.; Kostiv, U.; Brandmeier, J.C.; Horák, D.; Skládal, P.; Foret, F.; Gorris, H.H. Bioconjugates of photon-upconversion nanoparticles for cancer biomarker detection and imaging. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 1028–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, B.M.; Kukhta, N.A.; Huang, Y.; Luscombe, C.K. Ligand decomposition during nanoparticle synthesis: Influence of ligand structure and precursor selection. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, B.; McClements, D.J.; Xu, X.; Cui, S.; Gao, L.; Zhou, L.; Xiong, L.; Sun, Q.; Dai, L. Properties of curcumin-loaded zein-tea saponin nanoparticles prepared by antisolvent co-precipitation and precipitation. Food Chem. 2022, 391, 133224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Hemmati, S.; Pirhayati, M.; Zangeneh, M.M.; Veisi, H. Decoration of copper nanoparticles (Cu2O NPs) over chitosan-guar gum: Its application in the Sonogashira cross-coupling reactions and treatment of human lung adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, H.R.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Eş, I. Upconversion nanoparticles-modified aptasensors for highly sensitive mycotoxin detection for food quality and safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F 2024, 23, e13369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.T.; Chen, Y.; Tawfik, S.A.; Wen, S.; Parviz, M.; Shimoni, O.; Jin, D. Systematic investigation of functional ligands for colloidal stable upconversion nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 4842–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Dong, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Xu, L.; Yu, W.; Song, H. Amphiphilic silane modified NaYF4: Yb, Er loaded with Eu (TTA)3 (TPPO)2 nanoparticles and their multi-functions: Dual mode temperature sensing and cell imaging. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 8541–8549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, L.; Martínez, R.; Pardo, A.; Diez, I.; Velasco, B.; Moreda-Piñeiro, A.; Bermejo-Barrera, P.; Barbosa, S.; Taboada, P. Assessing the effect of surface coating on the stability, degradation, toxicity and cell endocytosis/exocytosis of upconverting nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2024, 668, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jin, D.; Stenzel, M.H. Polymer-functionalized upconversion nanoparticles for light/imaging-guided drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 3168–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroter, A.; Arnau del Valle, C.; Marín, M.J.; Hirsch, T. Bilayer-coating strategy for hydrophobic nanoparticles providing colloidal stability, functionality, and surface protection in biological media. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2023, 62, e202305165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Farivar, F.; De Prinse, T.J.; Rabiee, H.; Kidd, S.; Sumby, C.J.; Bi, J. Facile multistep synthesis of ZnO-coated β-NaYF4: Yb/Tm upconversion nanoparticles as an antimicrobial photodynamic therapy for persistent staphylococcus aureus small colony variants. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 6125–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhr, V.; Wilhelm, S.; Hirsch, T.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Upconversion nanoparticles: From hydrophobic to hydrophilic surfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3481–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, K.C.; Lawless, N.K.; Stewart, B.M.; Landers, J.P. Dielectric heating of highly corrosive and oxidizing reagents on a hybrid glass microfiber–polymer centrifugal microfluidic device. Lab A Chip 2022, 22, 2549–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, H.; Fard, S.M.B.; Rahimi, F.; Jannat, B.; Sadeghi, N. Ultrasound-assisted dispersive magnetic solid-phase extraction of cadmium, lead and copper ions from water and fruit juice samples using DABCO-based poly (ionic liquid) functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. Food Chem. 2022, 396, 133637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, E.S.G.; Cassella, R.J. Sugaring-out assisted extraction (SoAE): A novel approach for the determination of Cd and Pb in milk by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1369, 344347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Yin, J.; Yue, M.; Mu, Y. Microfluidic devices for multiplexed detection of foodborne pathogens. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, S.; Zhan, X.; Meng, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, K.; Su, S. Smartphone-based wearable microfluidic electrochemical sensor for on-site monitoring of copper ions in sweat without external driving. Talanta 2024, 266, 125015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Hassan, M.M.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q. Lanthanide ion (Ln3+)-based upconversion sensor for quantification of food contaminants: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3531–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Marks, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q. Thiazole derivative-modified upconversion nanoparticles for Hg2+ detection in living cells. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annavaram, V.; Chen, M.; Kutsanedzie, F.Y.; Agyekum, A.A.; Zareef, M.; Ahmad, W.; Hassan, M.M.; Huanhuan, L.; Chen, Q. Synthesis of highly fluorescent RhDCP as an ideal inner filter effect pair for the NaYF4: Yb, Er upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles to detect trace amount of Hg (II) in water and food samples. J. Photoch. Photobiol. A 2019, 382, 111950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Duan, N.; Shi, Z.; Fang, C.; Wang, Z. Dual fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay between tunable upconversion nanoparticles and controlled gold nanoparticles for the simultaneous detection of Pb2+ and Hg2+. Talanta 2014, 128, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhu, G.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shen, Y. Engineering of an upconversion luminescence sensing platform based on the competition effect for mercury-ion monitoring in green tea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 8565–8570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Cao, T.; Sun, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, Q.; Yang, T.; Yao, L.; Feng, W.; Li, F. A cyanine-modified nanosystem for in vivo upconversion luminescence bioimaging of methylmercury. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9869–9876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, R.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. Multifunctional upconversion nanoparticles based LRET aptasensor for specific detection of As (III) in aquatic products. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 369, 132271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Satra, J.; Srivastava, D.N.; Bhadu, G.R.; Adhikary, B. A highly sensitive luminescent upconversion nanosensor for turn-on detection of As3+. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 8874–8885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S.; Jiao, Y.; Wen, L.; Jiao, Y.; Tu, J.; Xing, K.; Cheng, Y. Target-triggered UCNPs/Fe3O4@ PCN-224 assembly for the detection of cadmium ions by upconversion fluorescence and magnetic relaxation switch dual-mode immunosensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 377, 133037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, T.; Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Song, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, H.; Hu, J. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer between NH2–NaYF4: Yb, Er/NaYF4@ SiO2 upconversion nanoparticles and gold nanoparticles for the detection of glutathione and cadmium ions. Talanta 2020, 207, 120294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Hou, S.; Zhao, S.; Guo, L.; Sun, A.; Hu, Q.; Pan, L.; Liu, Q.; Ding, C. Ursolic acid inhibiting excessive reticulophagic flux contributes to alleviate ochratoxin A-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress-and mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2025, 14, 9250181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, F.; Zong, X.; Lu, Q.; Wu, C.; Ni, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y. Near-infrared light excited UCNP-DNAzyme nanosensor for selective detection of Pb2+ and in vivo imaging. Talanta 2021, 227, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Kutsanedzie, F.Y.; Ali, S.; Wang, P.; Li, C.; Ouyang, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. Cysteamine-mediated upconversion sensor for lead ion detection in food. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 4849–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Xu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Nie, G. A novel “on-off-on” electrochemiluminescence strategy based on RNA cleavage propelled signal amplification and resonance energy transfer for Pb2+ detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1290, 342218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, T.; Liang, G.; Mo, J.; Zhu, J.; Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Ni, Z. A “turn off–on” fluorescent sensor for detection of Cr (Ⅵ) based on upconversion nanoparticles and nanoporphyrin. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 311, 124002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Zhang, X.B.; Wang, P.; Xu, S.H.; Liang, Z.Q.; Ye, C.Q.; Wang, X.M. Dye-sensitized lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoprobe for enhanced sensitive detection of Fe3+ in human serum and tap water. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 322, 124834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Mo, Z.; Tan, G.; Wen, H.; Chen, X.; Hakeem, D.A. PAA modified upconversion nanoparticles for highly selective and sensitive detection of Cu2+ ions. Front. Chem. 2021, 8, 619764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, D.; Zhao, T.; Zhao, L.; Fang, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, G. High-sensitivity sensing of divalent copper ions at the single upconversion nanoparticle level. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 11686–11691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholafazad, H.; Pazhuhi, M.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Voelcker, N.H.; Shadju, N.; Nilghaz, A. Cellulosic-based microneedles for sensing heavy metals in fish samples. Carbohydr. Polym. Tech. 2025, 10, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, P.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, C.; Gale, P.A.; et al. A hybrid strategy to enhance small-sized upconversion nanocrystals. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 271, 117003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Huang, P.; Shang, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, W.; Chen, X. Ultrafast upconversion superfluorescence with a sub-2.5 ns lifetime at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Guan, D.; Xia, X.; Ling, H.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chan, E.; Li, F.; Liu, Q. Sub-10 nm upconversion nanocrystals for long-term single-particle tracking. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Gonzalez, D.; Torres Vera, V.; Zabala Gutierrez, I.; Gerke, C.; Cascales, C.; Rubio-Retama, J.; Calderón, O.G.; Melle, S.; Laurenti, M. Upconverting nanoparticles in aqueous media: Not a dead-end road. avoiding degradation by using hydrophobic polymer shells. Small 2022, 18, 2105652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Wang, F. Overcoming thermal quenching in upconversion nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 3454–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Tao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, B. Amplifying photon upconversion in alloyed nanoparticles for a near-infrared photodetector. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 4580–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, P.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y. NIR-II upconversion nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 2985–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajdel, K.; Lobaz, V.; Ondra, M.; Konefał, R.; Moravec, O.; Pop-Georgievski, O.; Pánek, J.; Kalita, D.; Sikora-Dobrowolska, B.; Lenart, L.; et al. May the target be with you: Polysaccharide-coated upconverting nanoparticles for macrophage targeting. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 25120–25135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, K.; Kumar, B.; Piunno, P.A.; Krull, U.J. Cellular uptake of upconversion nanoparticles based on surface polymer coatings and protein corona. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 35985–36001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, J.; Zheng, X.; Lu, Y.; Piper, J.A.; Lu, Y.; Packer, N.H. Assessing the activity of antibodies conjugated to upconversion nanoparticles for immunolabeling. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1209, 339863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, H.S.; Ahn, Y.; Cho, Y.J.; Shin, H.H.; Hong, K.S.; Nam, S.H. Universal emission characteristics of upconverting nanoparticles revealed by single-particle spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2022, 17, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Yu, T.; Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhao, X.; Wei, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z. In vivo toxicity of upconversion nanoparticles (NaYF4: Yb, Er) in zebrafish during early life stages: Developmental toxicity, gut-microbiome disruption, and proinflammatory effects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 116905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, F.; Liu, J. Engineered lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles for biosensing and bioimaging application. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Ma, X.; Guo, J. Artificial intelligence reinforced upconversion nanoparticle-based lateral flow assay via transfer learning. Fundam. Res. 2022, 3, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Shi, Y.; Xin, W.; Liang, N.; Shen, T.; Xiao, J.; Daglia, M.; Zou, X.; et al. Dual modes of fluorescence sensing and smartphone readout for sensitive and visual detection of mercury ions in Porphyra. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1226, 340153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Strengths | Weaknesses | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvothermal method | Cheap raw materials; easy and effective operation; adjustable particle size, crystal phase, and morphology; relatively low reaction temperature; no requirement for high-temperature post-heat treatment | Difficult to screen for optimal synthesis conditions; requires specific reaction vessels; product size is generally large | [51,52] |

| Thermal decomposition method | The prepared product is highly crystalline, pure, and homogeneous, with good nanocrystalline morphology | The reaction requires high temperatures and anaerobic and anhydrous environments; the generation of toxic by-products and non-polar capping ligands limits its further application in food determination | [53,61,62] |

| Co-precipitation method | Does not require expensive instrumentation, stringent reaction conditions, and complex operating procedures; the synthesized products have high yields and fast growth rates | Poor product shape; uneven particle size; high temperature heat treatment required to obtain the product | [54,55,63] |

| Biological template method | Gentle and environmentally friendly; utilizes the natural structure of biomolecules to precisely regulate particle size, morphology, and bio-compatibility | Complex template removal; low yield; high temperature or extreme reaction conditions may destroy the template structure; residual biomolecules may affect the optical properties of the product, making it difficult to produce on a large scale | [56,64] |

| Types | Target Elements | Main Species | Types of Food | Detection Principles | Limit of Detection by the Developed Method | Recovery (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxic harmful heavy metals | Hg | Hg2+, MeHg | Tea, tap water | LRET, IFE, FRET | 0.15–13.5 nM | 97.20–112.00 | [79,80,81,82,83] |

| As | As3+, As5+ | aquatic products | LRET | 0.028 nM | 94.34–103.34 | [84,85] | |

| Cd | Cd2+ | egg, soymilk | FRET | 0.038–59.0 nM | 97.30–109.78 | [86,87,88] | |

| Trace elements for the human body | Pb | Pb2+ | Zebrafish, matcha, water | LRET, FRET | 2.6 × 10−4–500.0 nM | 93.99–102.16 | [89,90,91] |

| Cr | Cr3+, Cr6+ | Rice, fish | FRET | 360 nM | 92.00–108.20 | [92] | |

| Fe | Fe3+ | Tap water | LRET | 210 nM | 95.00–106.00 | [93] | |

| Cu | Cu2+ | Environmental water | FRET | 0.22–100 nM | Not mentioned | [94,95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Zhang, K.; He, Y. Research Progress on the Application of Upconversion Nanoparticles in Heavy Metal Detection in Foodstuff. Foods 2025, 14, 4144. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234144

Chen Z, Zhang K, He Y. Research Progress on the Application of Upconversion Nanoparticles in Heavy Metal Detection in Foodstuff. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4144. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234144

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhiqiang, Kangyao Zhang, and Ye He. 2025. "Research Progress on the Application of Upconversion Nanoparticles in Heavy Metal Detection in Foodstuff" Foods 14, no. 23: 4144. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234144

APA StyleChen, Z., Zhang, K., & He, Y. (2025). Research Progress on the Application of Upconversion Nanoparticles in Heavy Metal Detection in Foodstuff. Foods, 14(23), 4144. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234144