Effects of Steam Explosion-Assisted Extraction on the Structural Characteristics, Phenolic Profile, and Biological Activity of Valonea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

2.2. SE Pretreatment

2.3. Physicochemical Properties

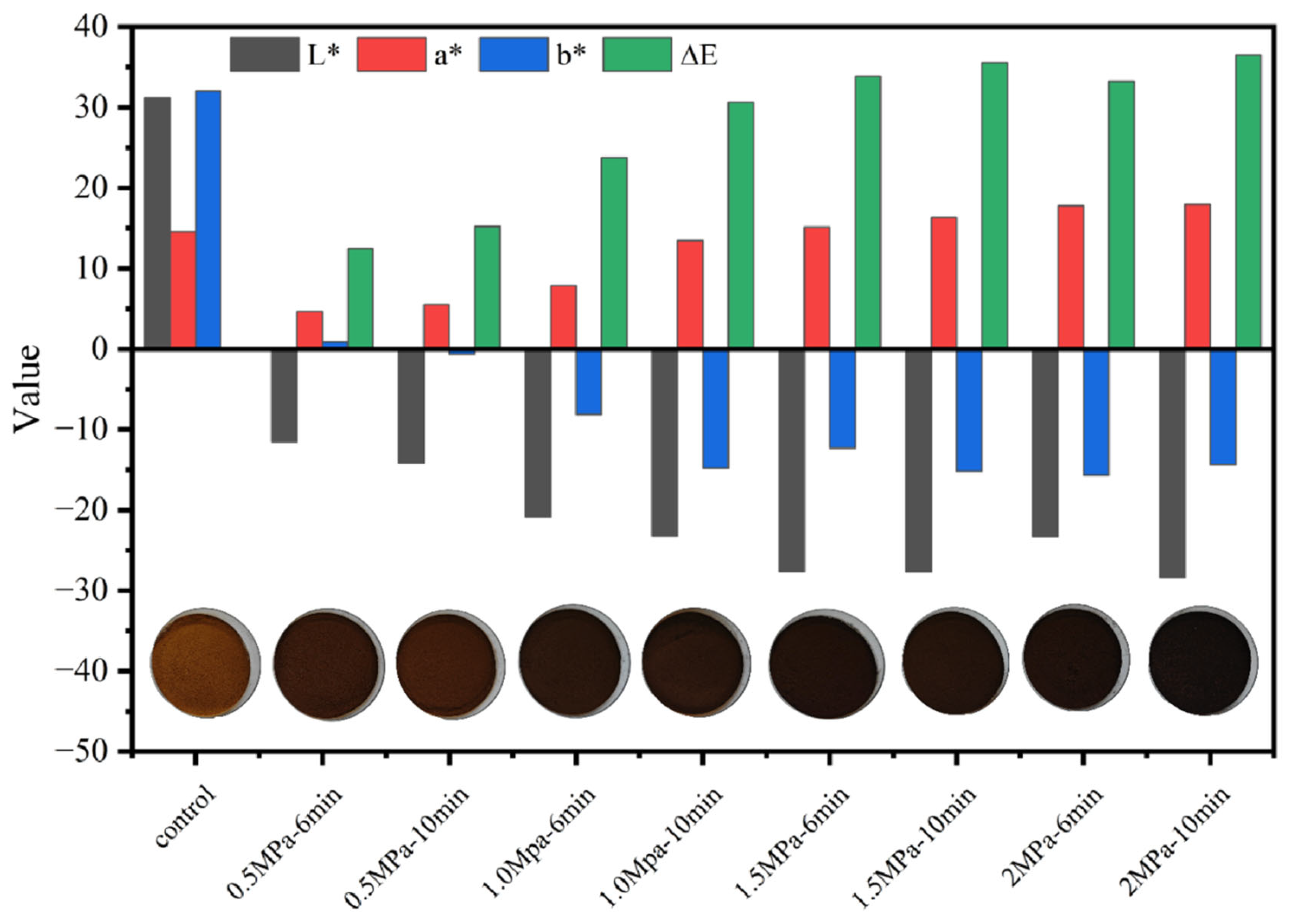

2.3.1. Color Measurement

2.3.2. Morphological Analysis

2.3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

2.3.4. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

2.4. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Valonea

2.4.1. Extraction and Identification of Phenolic Compounds

2.4.2. Kinetics of Polyphenol Extraction

2.5. Identification of Phenolic Compounds

2.6. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

2.7. Anti-Inflammatory Activity Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Valonea Appearance and Microstructure

3.2. FTIR Spectroscopy of Valonea

3.3. XRD Analysis of Valonea

3.4. Analysis of the Polyphenol Composition of Valonea

3.5. Kinetics of Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Valonea

3.6. High-Resolution MS

3.7. Antioxidant Activities of Valonea Extract

3.8. Anti-Inflammatory Activities

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hipp, A.L.; Manos, P.S.; Hahn, M.; Avishai, M.; Bodenes, C.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Crowl, A.A.; Deng, M.; Denk, T.; Fitz-Gibbon, S.; et al. Genomic landscape of the global oak phylogeny. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1198–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shao, Y.; Xi, J.; Yuan, Z.; Ye, Y.; Wang, T. Community Preferences of Woody Plant Species in a Heterogeneous Temperate Forest, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 00165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, N.; Chang, M.; Ge, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, G. Traits variation of acorns and cupules during maturation process in Quercus variabilis and Quercus aliena. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 196, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeriglio, A.; Barreca, D.; Bellocco, E.; Trombetta, D. Proanthocyanidins and hydrolysable tannins: Occurrence, dietary intake and pharmacological effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1244–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China, C.R.; Maguta, M.M.; Nyandoro, S.S.; Hilonga, A.; Kanth, S.V.; Njau, K.N. Alternative tanning technologies and their suitability in curbing environmental pollution from the leather industry: A comprehensive review. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, N.; Shende, A.P.; Mandal, S.K.; Ojha, N. Biologia Futura: Treatment of wastewater and water using tannin-based coagulants. Biol. Futur. 2022, 73, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufourc, E.J. Wine tannins and their aggregation/release with lipids and proteins: Review and perspectives for neurodegenerative diseases. Biophys. Chem. 2024, 307, 107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga-Corral, M.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Pereira, A.G.; Lourenco-Lopes, C.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Technological Application of Tannin-Based Extracts. Molecules 2020, 25, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoyos-Martínez, P.L.; Merle, J.; Labidi, J.; Charrier El Bouhtoury, F. Tannins extraction: A key point for their valorization and cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 1138–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y. Effect of steam explosion treatment on barley bran phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 7177–7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Ao, H.; Liu, W.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Ren, D. Physicochemical and structural properties of dietary fiber from Rosa roxburghii pomace by steam explosion. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 2381–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.B.; Liang, H.P.; Li, H.M.; Yuan, R.N.; Sun, J.; Zhang, L.L.; Han, M.H.; Wu, Y. Isolation, purification, characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from the stem barks of Acanthopanax leucorrhizus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Shan, S.; Cao, D.; Tang, D. Steam flash explosion pretreatment enhances soybean seed coat phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2020, 319, 126552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Qiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ou, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, B. Steam Explosion Pretreatment of Polysaccharide from Hypsizygus marmoreus: Structure and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2024, 13, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, X.; Ai, B.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Sheng, Z. Effect of steam explosion treatments on the functional properties and structure of camellia (Camellia oleifera Abel.) seed cake protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 93, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanpichai, S.; Witayakran, S.; Boonmahitthisud, A. Study on structural and thermal properties of cellulose microfibers isolated from pineapple leaves using steam explosion. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Kan, J.; Chen, G.; Du, M. Physicochemical, structure properties and in vitro hypoglycemic activity of soluble dietary fiber from adlay (Coix lachryma-jobi L. var. ma-yuen Stapf) bran treated by steam explosion. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1124012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, T.; Liu, P. Steam explosion pretreatment of Achyranthis bidentatae radix: Modified polysaccharide and its antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zheng, P.; Dai, W.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, X.; Hu, J.; Zeng, S.; Lin, S. Steam Explosion-Assisted Extraction of Polysaccharides from Pleurotus eryngii and Its Influence on Structural Characteristics and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2024, 13, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Lu, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H. Steam explosion improved the physicochemical properties, hypoglycemic effects of polysaccharides from Clerodendranthus spicatus leaf via regulating IRS1/PI3K/AKT/GSK-3beta signaling pathway in IR-HepG2 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yuan, T.; Zhu, X.; Song, G.; Wang, D.; Li, L.; Huang, M.; Gong, J. The phenolics, antioxidant activity and in vitro digestion of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peels: An investigation of steam explosion pre-treatment. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1161970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Hou, C.; Luo, K.; Cheng, A. Steam explosion enhances phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity in mung beans. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, C.; Kong, X.; Lei, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C. Effects of steam explosion pretreatment on the physicochemical properties, phenolic profile and its antioxidant activities of Baphicacanthus cusia (Nees) Bremek. leaves. LWT 2024, 214, 117126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Liu, R.; Cai, J.; Cui, Q. A new five-parameter logistic model for describing the evolution of energy consumption. Energy Sources Part. B Econ. Plan. Policy 2016, 11, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Kuang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Z.-H. Effect of steam explosion on physicochemical properties and fermentation characteristics of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 129, 109579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, W.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, R.; Wu, T.; Zhang, M. Steam explosion modification on tea waste to enhance bioactive compounds’ extractability and antioxidant capacity of extracts. J. Food Eng. 2019, 261, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lin, M.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z. Improvement of soluble dietary fiber quality in Tremella fuciformis stem by steam explosion technology: An evaluation of structure and function. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.R.; Pattnaik, F.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Meda, V.; Naik, S. Hydrothermal pretreatment technologies for lignocellulosic biomass: A review of steam explosion and subcritical water hydrolysis. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Feng, C.; Luo, K.; Cui, W.; Xia, Z.; Cheng, A. Effect of steam explosion on phenolics and antioxidant activity in plants: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D. Research on Extraction, Purification and Property of Acorn Shell Brown Pigment. Master’s Thesis, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H. Extration and Separation and Function of Acorn Shell Polyphenols. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Y.; Jian, J. Effect of Steam Explosion Pretreatment on Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Acorn Shells. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2014, 35, 2565–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L. Effect and Mechanism of Ethanol Extraction from Quercus Variabilis Acorn Shell on Wheat Starch Digestion and Absorption. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y. Study on the Separation, Purification and Physicochemical Properties of Pigments from Quercus variabilis Acorn Shells. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.; Liu, J.; Shui, R.; Sun, J.; Weng, Q.; Qiu, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, S.; Xiao, G.; Chen, X.; et al. Effect of steam explosion pretreatment on the composition and bioactive characteristic of phenolic compounds in Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat cv. Hangbaiju powder with various sieve fractions. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Li, D.; Jiang, W.; Qin, Z.; Zhao, S.; Qiu, M.; Wu, J. Two ellagic acid glycosides from Gleditsia sinensis Lam. with antifungal activity on Magnaporthe grisea. Nat. Prod. Res. 2007, 21, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J. Antibacterial phenolic compounds from the spines of Gleditsia sinensis Lam. Nat. Prod. Res. 2007, 21, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Xiao, Z.; Li, T.; Guo, G.; Chen, S.; Huang, X. Improving the quality of soluble dietary fiber from Poria cocos peel residue following steam explosion. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masci, A.; Coccia, A.; Lendaro, E.; Mosca, L.; Paolicelli, P.; Cesa, S. Evaluation of different extraction methods from pomegranate whole fruit or peels and the antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of the polyphenolic fraction. Food Chem. 2016, 202, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romier, B.; Van De Walle, J.; During, A.; Larondelle, Y.; Schneider, Y.J. Modulation of signalling nuclear factor-kappaB activation pathway by polyphenols in human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahfoufi, N.; Alsadi, N.; Jambi, M.; Matar, C. The Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Polyphenols. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossou, M.C.B.; Blachier, F.; Yin, Y.; Tan, B.E.; Tarique, H.; Rahu, N.; Rupasinghe, V. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: What Polyphenols Can Do for Us? Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 7432797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, E.; Dell’Agli, M. Special Issue: Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Plant Polyphenols. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | A2 (mg/g) | x0 (min) | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 388.95426 ± 9.43556 | 11.54059 ± 0.96452 | 1.77479 ± 0.22152 | 0.9931 |

| 0.5 MPa-6 min | 549.08216 ± 9.51691 | 7.29869 ± 0.43312 | 1.17193 ± 0.0954 | 0.99782 |

| 0.5 MPa-10 min | 567.59228 ± 11.76504 | 6.83526 ± 0.49375 | 1.16763 ± 0.11876 | 0.99676 |

| 1 MPa-6 min | 509.56125 ± 8.17797 | 8.41025 ± 0.45568 | 1.23287 ± 0.08833 | 0.99809 |

| 1 MPa-10 min | 633.62246 ± 14.94848 | 5.77421 ± 0.48996 | 1.11002 ± 0.13843 | 0.99594 |

| 1.5 MPa-6 min | 500.5555 ± 10.09776 | 8.57882 ± 0.59122 | 1.27969 ± 0.11773 | 0.99673 |

| 1.5 MPa-10 min | 472.94735 ± 7.25013 | 9.45111 ± 0.4858 | 1.31104 ± 0.08793 | 0.99817 |

| 2 MPa-6 min | 476.36278 ± 5.44033 | 9.53215 ± 0.35886 | 1.26801 ± 0.06108 | 0.99907 |

| 2 MPa-10 min | 362.19496 ± 5.34553 | 12.74958 ± 0.60884 | 1.70708 ± 0.11866 | 0.99789 |

| No. | Compounds | Molecular Formula | Type | MS/MS (+) | Fragments (+) (m/z) | Ion Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loureirin B | C17H18O5 | Polyphenol | 318.3 | 147.04; 117.03; 108.02 | 1.5 × 1010 |

| 2 | Dihydroferulic acid | C10H12O4 | Polyphenol | 197.1 | 109.03; 151.06; 136.04 | 5 × 109 |

| 3 | Phloretic acid | C9H10O3 | Polyphenol | 167.1 | 121.06; 107.05; 149.06 | 1.5 × 1010 |

| 4 | Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) | C22H18O11 | Polyphenol | 471 | 139.03; 179.03; 247.08; 138.02; 242.15 | 8 × 108 |

| 5 | Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | Polyphenol | 193.1 | 126.17; 108.95 | 1.2 × 1010 |

| 6 | Phloretin | C15H14O5 | Polyphenol | 274.3 | 122.06; 107.07 | 1.6 ×1010 |

| 7 | Ellagic acid | C14H6O8 | Polyphenol | 303 | 259.02; 283.08; 184.93 | 8 × 108 |

| 8 | Dihydrocaffeic acid | C9H10O4 | Polyphenol | 183.1 | 178.09; 136.95 | 1.5 × 109 |

| 9 | Catechin gallate | C22H18O10 | Polyphenol | 443.2 | 179.03; 247.08; 138.02; 242.15 | 1.5 × 108 |

| 10 | Methyl gallate | C8H8O5 | Polyphenol | 185 | 141.19; 126.17; 108.95 | 6 × 108 |

| 11 | Arginine | C6H14N4O2 | Amino Acid | 197.1 | 100.08; 132.09 | 9 × 109 |

| 12 | Quercetin | C15H10O7 | Polyphenol | 303.1 | 195.03; 167.07 | 3 × 106 |

| 13 | Protocatechuic acid | C7H6O4 | Polyphenol | 153 | 109.02 | 7 × 107 |

| 14 | Ilexolic acid | C30H48O4 | Terpenoids | 488.3 | 471.34; 423.32; 287.25 | 5 × 106 |

| 15 | Stigmast-4-ene-3,6-dione | C29H46O2 | Terpenoids | 427 | 383.29; 312.21; 202.10; 137.06 | 2 × 106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, Z.; Li, W.; Jiang, J.; Wang, C. Effects of Steam Explosion-Assisted Extraction on the Structural Characteristics, Phenolic Profile, and Biological Activity of Valonea. Foods 2025, 14, 4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234096

Tong Z, Li W, Jiang J, Wang C. Effects of Steam Explosion-Assisted Extraction on the Structural Characteristics, Phenolic Profile, and Biological Activity of Valonea. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234096

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Zhenkai, Wenjun Li, Jianxin Jiang, and Chengzhang Wang. 2025. "Effects of Steam Explosion-Assisted Extraction on the Structural Characteristics, Phenolic Profile, and Biological Activity of Valonea" Foods 14, no. 23: 4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234096

APA StyleTong, Z., Li, W., Jiang, J., & Wang, C. (2025). Effects of Steam Explosion-Assisted Extraction on the Structural Characteristics, Phenolic Profile, and Biological Activity of Valonea. Foods, 14(23), 4096. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234096