Comprehensive Investigation of Grade-Specific Aroma Signatures in Nongxiangxing Baijiu Using Flavoromics Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Reagents

2.3. Sensory Evaluation

2.4. Electronic Nose Analysis

2.5. Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy Analysis

2.6. GC-MS Analysis of Volatile Compounds

2.6.1. Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME)

2.6.2. GC-MS

2.7. Quantitative Analysis of Volatile Compounds by GC-FID

2.8. Calculation of Odor Activity Values (OAVs)

2.9. Aroma Recombination and Omission Experiments

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Aroma Profiles of NXB in Different Grade

3.1.1. Sensory Evaluation of NXB in Different Grade

3.1.2. Electronic Nose Analysis of NXB in Different Grade

3.1.3. Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy Analysis of NXB in Different Grade

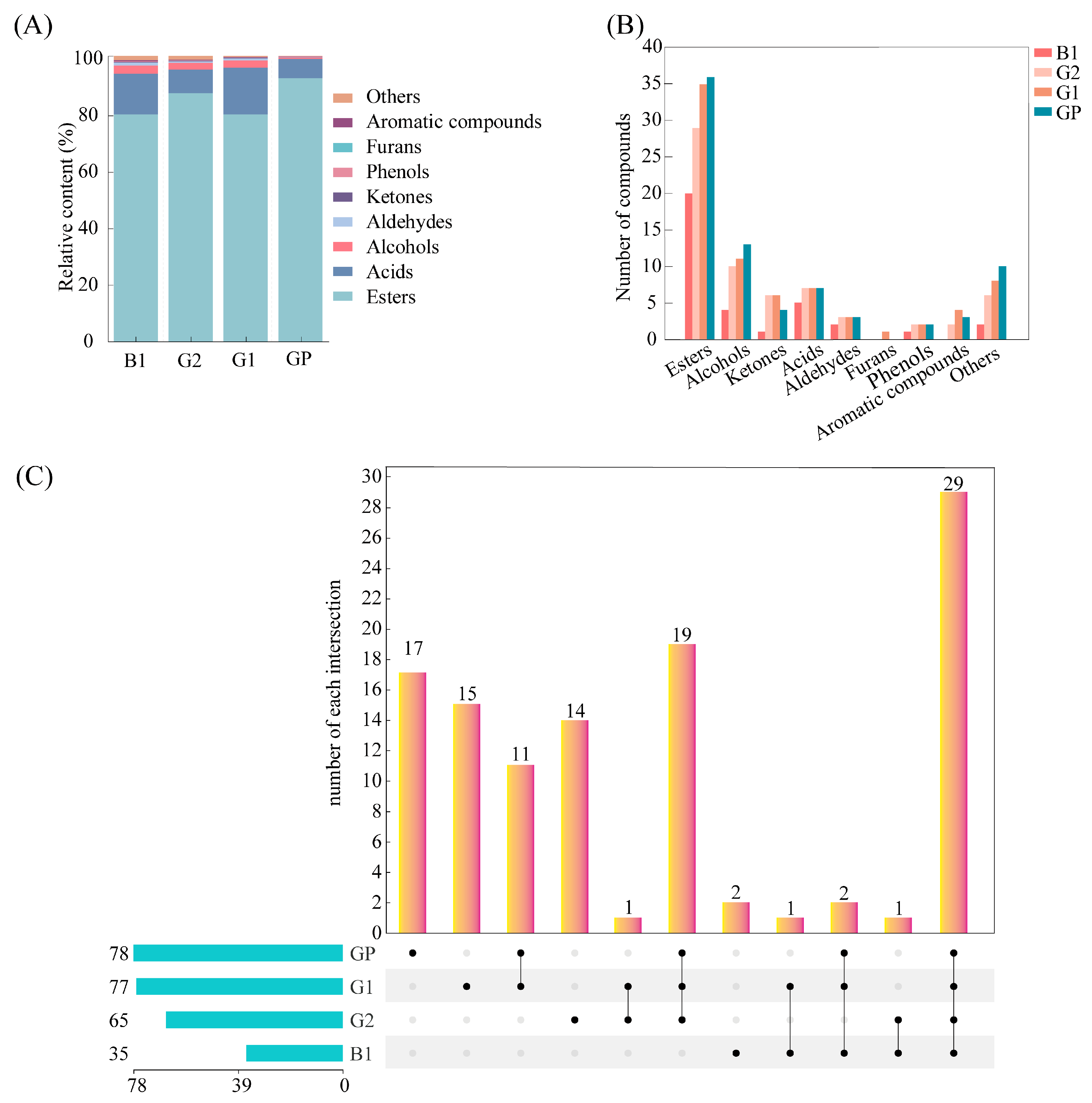

3.2. The Types of Volatile Compounds of NXB in Different Grades

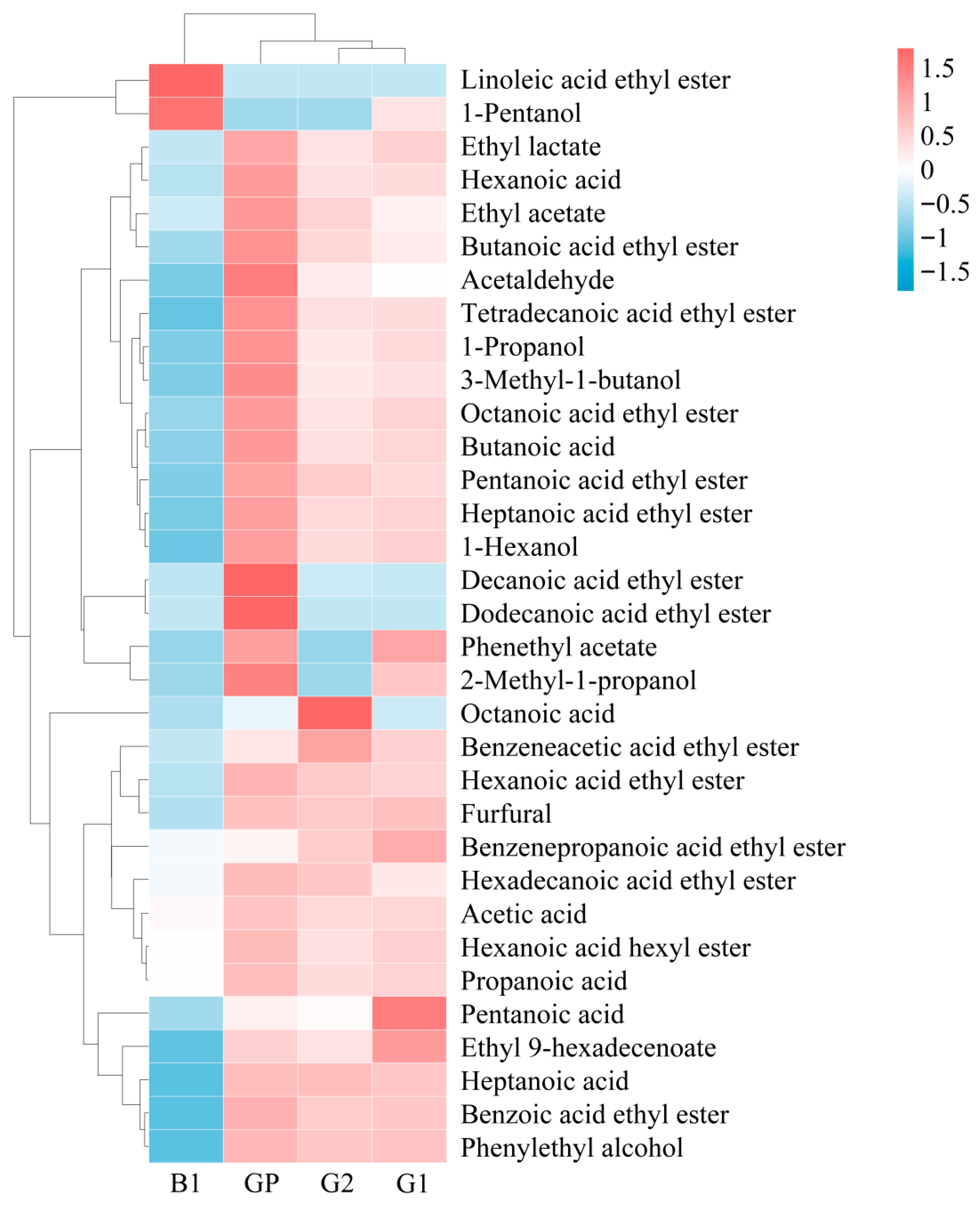

3.3. Quantitative Analysis of Volatile Compounds

3.4. OAV Analysis of Aroma Compounds

3.5. Key Aroma Compounds of NXB in Different Grades

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Xiong, A.; Liu, L.; Tong, R.; Pei, W.; Yang, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z. Baijiu: Chemical composition, biological functions, and endogenous metabolic profiles. Food Res. Int. 2025, 219, 116895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.S.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y.S.; Zhao, D.R. Uncover the flavor code of strong-aroma baijiu: Research progress on the revelation of aroma compounds in strong-aroma baijiu by means of modern separation technology and molecular sensory evaluation. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 109, 104499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, R.Q.; Zhang, S.Y.; Qin, H.; Tang, H.L.; Pan, Q.L.; Tang, H.F. Characterization of the differences in aroma-active compounds in strongflavor Baijiu induced by bioaugmented Daqu using metabolomics and sensomics approaches. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.R.; Shi, D.M.; Sun, J.Y.; Li, A.J.; Sun, B.G.; Zhao, M.M.; Chen, F.; Sun, X.T.; Li, H.H.; Huang, M.Q.; et al. Characterization of key aroma compounds in Gujinggong Chinese Baijiu by gas chromatography-olfactometry, quantitative measurements, and sensory evaluation. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.X.; Liu, Z.P.; Qian, M.; Yu, X.W.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S. Unraveling the chemosensory characteristics of strong-aroma type Baijiu from different regions using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry and descriptive sensory analysis. Food Chem. 2020, 127335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.X.; Wang, J.S.; Zhang, C.S.; Zhao, Z.G.; Tian, W.J.; Wu, Y.S.; Chen, H.; Zhao, D.R.; Sun, J.Y. Unraveling variation on the profile aroma compounds of strong aroma type of Baijiu in different regions by molecular matrix analysis and olfactory analysis. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 33511–33521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Yang, S.Q.; Zhang, G.H.; Xu, L.; Li, H.H.; Sun, J.Y.; Huang, M.Q.; Zheng, F.P.; Sun, B.G. Exploration of key aroma active compounds in strong flavor Baijiu during the distillation by modern instrument detection technology combined with multivariate statistical analysis methods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 110, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.S.; Guo, X.G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.Q.X.; Yang, L.H.; Mou, W.L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Chemometrics combined with comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for the identification of Baijiu vintage. Food Chem. 2024, 444, 138690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W. A systematic review of multimodal fusion technologies for food quality and safety assessment: Recent advances and future trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 164, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ma, Y.; Tian, X.; Li, M.J.; Li, L.X.; Tang, K.; Xu, Y. Chemosensory characteristics of regional Vidal icewines from China and Canada. Food Chem. 2018, 261, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Guo, R.N.; Liu, M.; Shen, C.H.; Sun, X.T.; Zhao, M.M.; Sun, J.Y.; Li, H.H.; Zheng, F.P.; Huang, M.Q.; et al. Characterization of key odorants causing the roasted and mud-like aromas in strong-aroma types of base Baijiu. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, L.; Schieberle, P. Characterization of the key aroma compounds in an American Bourbon whisky by quantitative measurements, aroma recombination, and omission studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5820–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 33405-2016; Guidelines for Sensory Evaluation of Baijiu. International Organization for Standardization: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; Zheng, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, H.; Du, L. Impact of organic acids on aroma release in light-flavor baijiu: A focus on key aroma-active compounds. Food Biosci. 2025, 65, 106071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Ru, H.; Wang, J.; Kuang, J.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, Q. Odor threshold dynamics during baijiu aging: Ester-acid interactions. LWT 2025, 217, 117436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tan, H.; Bai, J.; Li, J.; Li, A.; Ma, L.; Yuan, L.; Wei, C.; et al. Decoding the aroma characterization and influencing factor in the core brewing process of China’s northern sauce-flavored baijiu. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 144, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.L.; Xu, Y. Determination of odor thresholds of volatile aroma compounds in baijiu by a forced-choice ascending concentration series method of limits. Liquor. Mak. 2011, 38, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, M.C.; Wang, Y. Seasonal variation of volatile composition and odor activity value of ‘Marion’ (Rubus spp. hyb) and ‘Thornless Evergreen’ (R. laciniatus L.) blackberries. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, C13–C20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Y.; Li, Q.Y.; Luo, S.Q.; Zhang, J.L.; Huang, M.Q.; Chen, F.; Zheng, F.P.; Sun, X.T.; Li, H.H. Characterization of key aroma compounds in Meilanchun sesame flavor style baijiu by application of aroma extract dilution analysis, quantitative measurements, aroma recombination, and omission/addition experiments. Rsc. Adv. 2018, 8, 23757–23767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.W.; Yao, Z.M.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, Z.B.; Ma, N.; Zhu, J.C. Characterization of the key aroma compounds in different light aroma type Chinese liquors by GC-olfactometry, GC-FPD, quantitative measurements, and aroma recombination. Food Chem. 2017, 233, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, W.; Xu, Y. Comparison on aroma compounds in Chinese soy sauce and strong aroma type liquors by gas chromatography-olfactometry, chemical quantitative and odor activity values analysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2014, 239, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Wang, X.L.; Zhao, Y.F.; Zheng, F.P.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, F.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Chen, F. Characterization of key aroma compounds in Laobaigan Chinese Baijiu by GC×GC-TOF/MS and means of molecular sensory science. Flavour. Frag. J. 2019, 34, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.W.; Zhu, Q.; Xiao, Z. Characterization of perceptual interactions among ester aroma compounds found in Chinese Moutai Baijiu by gas chromatography-olfactometry, odor Intensity, olfactory threshold and odor activity value. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.Z.; Du, J.W.; Xiong, Y.Q.; Cao, Q.W.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.J.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Y.H.; Liu, Y.C. Characterization of the key aroma compounds in Chinese JingJiu by quantitative measurements, aroma recombination, and omission experiment. Food Chem. 2021, 352, 129450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.B.; Yu, D.; Niu, Y.W.; Ma, N.; Zhu, J.C. Characterization of different aroma-types of chinese liquors based on their aroma profile by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and sensory evaluation. Flavour. Frag. J. 2016, 31, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Bai, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Hua, Y.; Wang, T.; Yang, J. Rapid geographical origin identification and functional compound content prediction of chrysanthemum (“gongju”) using excitation–emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Chen, W.; Li, W.H.; Yu, H.Q. A chemometric analysis on the fluorescent dissolved organic matter in a full-scale sequencing batch reactor for municipal wastewater treatment. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2017, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhardt, L.; Bro, R.; Zeković, L.; Dramićanin, T.; Dramićanin, D.M. Fluorescence spectroscopy coupled with PARAFAC and PLS DA for characterization and classification of honey. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, T.Q.; Yin, X.L.; Sun, W.; Ding, W.; Ma, L.A.; Gu, H.W. Developing an Excitation-Emission Matrix Fluorescence Spectroscopy Method Coupled with Multi-way Classification Algorithms for the Identification of the Adulteration of Shanxi Aged Vinegars. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 2306–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.C.; Yu, H.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Gu, H.W.; Yin, X.L. Rapid authentication of green tea grade by excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy coupled with multi-way chemometric methods. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 249, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y.; Gu, H.W.; Wang, Y.; Geng, T.; Cui, H.N.; Pan, Y.; Ding, B.M.; Li, Z.S.; Yin, X.L. Excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy combined with multi-way chemometric methods for rapid qualitative and quantitative analyses of the authenticity of sesame oil. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 2087–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Geng, T.; Yan, M.L.; Peng, Z.X.; Chen, Y.; Lv, Y.; Yin, X.L.; Gu, H.W. Geographical origin traceability and authenticity detection of Chinese red wines based on excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy and chemometric methods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 125, 105763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Qian, M.C. Characterization of aroma compounds of Chinese “Wuliangye” and “Jiannanchun” liquors by aroma extract dilution analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2695–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Pan, J.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X. Dmu-spme variable temperature extraction: Revealing the flavor characteristics of strong-aroma baijiu by volatilomics. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ru, L.; Wu, C.; Zhou, R.; Liao, X. Discrimination of different kinds of Luzhou-flavor raw liquors based on their volatile features. Food Res. Int. 2014, 56, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.P.; Li, Z.; Qi, T.T.; Li, X.J.; Pan, S.Y. Development of a method for identification and accurate quantitation of aroma compounds in Chinese Daohuaxiang liquors based on SPME using a sol-gel fibre. Food Chem. 2015, 169, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Q.; Zhao, J.R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.S.; Zhao, Z.G.; Li, X.T.; Sun, B.G. Flavor mystery of Chinese traditional fermented baijiu: The great contribution of ester compounds. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S.; Hou, Y.X.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.S.; Zhang, C.S.; Zhao, Z.G.; Ao, R.; Huang, H.; Hong, J.X.; Zhao, D.R.; et al. “Key Factor” for Baijiu Quality: Research Progress on Acid Substances in Baijiu. Foods 2022, 11, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Linear Range (mg/L) | Linear Equation | R2 | Content (mg/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | G2 | G1 | GP | ||||

| Ethyl acetate | 50.40–5040.30 | y = 1.0876x + 8.9314 | 0.9998 | 492.16 ± 12.62 | 901.46 ± 8.46 | 750.79 ± 9.60 | 1211.82 ± 10.57 |

| Butanoic acid ethyl ester | 20.00–1999.70 | y = 1.5369x + 9.4252 | 0.9998 | 40.94 ± 0.64 | 114.67 ± 7.25 | 99.04 ± 3.42 | 166.47 ± 2.36 |

| Pentanoic acid ethyl ester | 1.01–403.86 | y = 1.6892x + 1.4572 | 0.9999 | 4.33 ± 0.16 | 22.68 ± 1.31 | 20.92 ± 0.71 | 29.10 ± 1.28 |

| Hexanoic acid ethyl ester | 9.94–993.75 | y = 1.8108x + 3.0277 | 0.9998 | 558.60 ± 3.64 | 1193.86 ± 4.57 | 1146.18 ± 1.76 | 1348.93 ± 9.10 |

| Heptanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.22–2228.43 | y = 1.9640x + 0.1755 | 0.9999 | 0.74 ± 0.12 | 4.70 ± 0.17 | 4.82 ± 0.29 | 6.64 ± 0.57 |

| Ethyl lactate | 54.38–5437.80 | y = 0.9938x − 1.7341 | 0.9999 | 337.98 ± 8.07 | 603.74 ± 8.10 | 670.12 ± 7.46 | 838.89 ± 8.91 |

| Octanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.13–131.97 | y = 2.0698x − 0.6619 | 0.9999 | 1.31 ± 0.10 | 3.93 ± 0.11 | 4.33 ± 0.19 | 5.91 ± 0.37 |

| Hexanoic acid hexyl ester | 0.46–92.50 | y = 0.8775x + 2.340 | 0.9956 | 8.04 ± 0.29 | 9.91 ± 0.30 | 10.73 ± 0.18 | 11.91 ± 0.40 |

| Decanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.01–127.73 | y = 2.0416x − 3.8535 | 0.9977 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 3.78 ± 0.21 | 2.21 ± 0.23 | 74.44 ± 0.09 |

| Benzoic acid ethyl ester | 0.13–133.03 | y = 2.0874x − 3.2949 | 0.9995 | ND a | 4.77 ± 0.02 | 4.91 ± 0.02 | 5.65 ± 0.01 |

| Benzeneacetic acid ethyl ester | 0.11–105.47 | y = 2.1660x − 5.8542 | 0.9992 | 1.82 ± 0.13 | 4.52 ± 0.06 | 3.56 ± 0.04 | 3.14 ± 0.11 |

| Phenethyl acetate | 0.12–124.02 | y = 2.0417x − 5.0071 | 0.9993 | ND | ND | 1.17 ± 0.11 | 1.21 ± 0.05 |

| Dodecanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.09–90.00 | y = 1.1319x − 5.4185 | 0.9984 | ND | ND | ND | 9.86 ± 0.16 |

| Benzenepropanoic acid ethyl ester | 2.62–130.91 | y = 2.0345x − 5.6279 | 0.9992 | 5.02 ± 0.45 | 7.23 ± 0.51 | 8.56 ± 0.23 | 5.76 ± 0.12 |

| Linoleic acid ethyl ester | 0.18–180.00 | y = 0.9318x +0.3677 | 0.9998 | 20.41 ± 0.76 | ND | ND | ND |

| Tetradecanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.08–81.90 | y = 0.7825x + 0.4512 | 0.9984 | ND | 29.36 ± 0.08 | 30.13 ± 0.54 | 49.01 ± 0.51 |

| Hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester | 2.57–428.50 | y = 0.7891x − 5.6723 | 0.9985 | 46.23 ± 0.36 | 68.34 ± 1.23 | 56.78 ± 0.92 | 72.31 ± 0.65 |

| Ethyl 9-hexadecenoate | 0.10–97.44 | y = 0.3373x − 13.8479 | 0.9958 | ND | 12.89 ± 1.14 | 20.36 ± 0.21 | 14.84 ± 0.17 |

| Acetic acid | 80.77–2019.30 | y = 0.7445x − 50.7577 | 0.9985 | 458.24 ± 0.03 | 546.04 ± 1.02 | 554.63 ± 0.61 | 607.39 ± 3.01 |

| Propanoic acid | 1.99–199.81 | y = 1.1913x − 8.5085 | 0.9984 | 8.96 ± 0.26 | 10.99 ± 0.24 | 11.50 ± 0.30 | 12.86 ± 0.38 |

| Butanoic acid | 8.18–409.16 | y = 1.4708x − 18.5989 | 0.9983 | 21.23 ± 0.01 | 74.44 ± 0.01 | 78.97 ± 0.01 | 113.04 ± 0.01 |

| Pentanoic acid | 0.11–112.68 | y = 1.6725x + 7.8123 | 0.9943 | 1.88 ± 0.12 | 5.02 ± 0.68 | 11.55 ± 0.44 | 5.64 ± 0.68 |

| Hexanoic acid | 7.95–397.50 | y = 1.6337x − 19.4822 | 0.9981 | 259.91 ± 0.01 | 516.43 ± 0.01 | 531.19 ± 0.01 | 743.14 ± 0.05 |

| Heptanoic acid | 0.14–137.70 | y = 0.8459x + 6.7832 | 0.9995 | ND | 7.02 ± 0.34 | 6.53 ± 0.09 | 6.97 ± 0.04 |

| Octanoic acid | 0.13–127.40 | y = 0.5890x + 8.874 | 0.9980 | ND | 14.48 ± 1.11 | 1.31 ± 0.49 | 2.80 ± 0.35 |

| 1-Propanol | 4.04–4041.80 | y = 1.7244x + 15.2927 | 0.9999 | 20.16 ± 0.80 | 98.38 ± 3.41 | 110.65 ± 0.05 | 166.10 ± 6.02 |

| 2-Methyl-1-Propanol | 0.39–394.85 | y = 2.0471x + 0.6496 | 0.9999 | ND | ND | 31.00 ± 0.30 | 47.96 ± 1.69 |

| 1-Pentanol | 0.12–119.25 | y = 2.1360x + 0.0251 | 0.9999 | 3.44 ± 0.23 | ND | 1.50 ± 0.01 | ND |

| 3-Methyl-1-Butanol | 8.01–801.36 | y = 2.0942x + 1.3986 | 0.9999 | 18.22 ± 0.35 | 117.63 ± 1.47 | 126.94 ± 3.67 | 214.02 ± 5.21 |

| 1-Hexanol | 0.98–97.68 | y = 0.4681x − 1.2937 | 0.9924 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | 12.23 ± 0.36 | 13.32 ± 0.10 | 17.69 ± 0.14 |

| Phenylethyl Alcohol | 0.15–153.70 | y = 2.0945x − 8.7875 | 0.9970 | ND | 5.18 ± 0.04 | 5.25 ± 0.08 | 5.67 ± 0.06 |

| Acetaldehyde | 0.38–3861.10 | y = 0.4229x + 10.3323 | 0.9997 | ND | 281.33 ± 4.90 | 230.70 ± 2.57 | 602.28 ± 2.63 |

| Furfural | 4.05-–405.45 | y = 1.3037x − 1.8545 | 0.9998 | 18.44 ± 2.28 | 41.99 ± 0.59 | 43.92 ± 1.95 | 43.93 ± 6.13 |

| Compound | Threshold (μg/L) | Aroma Description | OAV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | G2 | G1 | GP | |||

| Ethyl acetate | 32,551.6 [16] | fruity | 15.12 | 27.69 | 23.06 | 37.23 |

| Butanoic acid ethyl ester | 81.5 [16] | fruity, floral | 502.33 | 1406.99 | 1215.21 | 2042.58 |

| Pentanoic acid ethyl ester | 26.78 [16] | fruity, floral | 161.69 | 846.9 | 781.18 | 1086.63 |

| Hexanoic acid ethyl ester | 55.33 [16] | fruity, fermented | 10,095.79 | 21,577.08 | 20,715.34 | 24,379.72 |

| Heptanoic acid ethyl ester | 13,153.17 [16] | floral, sweet aromatic | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Ethyl lactate | 128,083.8 [20] | fruity, sweet aromatic | 2.64 | 4.71 | 5.23 | 6.55 |

| Octanoic acid ethyl ester | 12.87 [16] | fruity, sweet aromatic | 101.79 | 305.36 | 336.44 | 459.21 |

| Hexanoic acid hexyl ester | 1890 [9] | fruity | 4.25 | 5.24 | 5.68 | 6.30 |

| Decanoic acid ethyl ester | 1122.3 [16] | fruity, floral | <1 | 3.37 | 1.97 | 66.33 |

| Benzoic acid ethyl ester | 1433.65 [16] | honey, floral | ND a | 3.33 | 3.42 | 3.94 |

| Benzeneacetic acid ethyl ester | 407 [13] | honey, floral | 4.47 | 11.11 | 8.75 | 7.71 |

| Phenethyl acetate | 909 [13] | floral, sweet aromatic | ND | ND | 1.29 | 1.33 |

| Dodecanoic acid ethyl ester | 350 [21] | floral, sweet aromatic | ND | ND | ND | 28.17 |

| Benzenepropanoic acid ethyl ester | 125 [13] | fruity, honey | 40.16 | 57.84 | 68.48 | 46.08 |

| Tetradecanoic acid ethyl ester | 500 [22] | floral | ND | 58.72 | 60.26 | 98.02 |

| Hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester | 39,299 [18] | fruity, creamy | 1.18 | 1.74 | 1.44 | 1.84 |

| Acetic acid | 160,000 [13] | sour aromatic | 2.86 | 3.41 | 3.47 | 3.8 |

| Propanoic acid | 18,100 [9] | sour aromatic | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Butanoic acid | 964.164 [16] | cheesy, sour aromatic | 22.01 | 77.17 | 81.86 | 117.18 |

| Pentanoic acid | 389.11 [16] | sweaty, sour aromatic | 4.83 | 12.9 | 29.68 | 14.49 |

| Hexanoic acid | 2517.16 [16] | sweaty, fermented | 103.26 | 205.16 | 211.03 | 295.23 |

| Heptanoic acid | 13,821.32 [16] | sweaty, sour aromatic | ND | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Octanoic acid | 2701.23 [16] | cheesy, sour aromatic | ND | 5.36 | <1 | 1.04 |

| 1-Propanol | 53,952.63 [16] | alcoholic | <1 | 1.82 | 2.05 | 3.08 |

| 2-Methyl-1-propanol | 28,300 [13] | alcoholic, malt | ND | ND | 1.1 | 1.69 |

| 1-Pentanol | 6400 [19] | alcoholic | <1 | ND | <1 | ND |

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol | 179,190.83 [16] | alcoholic, malt | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1.19 |

| 1-Hexanol | 2500 [17] | alcoholic | <1 | 4.89 | 5.33 | 7.08 |

| Phenylethyl alcohol | 28,900 [13] | floral | ND | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Acetaldehyde | 500 [1] | grass, fresh | ND | 562.66 | 461.4 | 1204.56 |

| Furfural | 44,029.73 [16] | roast | <1 | <1 | 1 | 1 |

| Model | Compounds Removed from the Recombinant Model | Significant Difference a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | G2 | G1 | GP | ||

| 1 | All ester compounds | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| 1ND1 | Ethyl acetate | * | ** | * | ** |

| 1-2 | Butanoic acid ethyl ester | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| 1-3 | Pentanoic acid ethyl ester | * | ** | ** | *** |

| 1-4 | Hexanoic acid ethyl ester | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| 1-5 | Ethyl lactate | * | * | ** | *** |

| 1-6 | Octanoic acid ethyl ester | * | ** | ** | *** |

| 1-7 | Hexanoic acid hexyl ester | * | * | * | ** |

| 1-8 | Decanoic acid ethyl ester | ND b | - | - | * |

| 1-9 | Benzoic acid ethyl ester | ND | - | * | ** |

| 1-10 | Benzeneacetic acid ethyl ester | * | ** | * | * |

| 1-11 | Phenethyl acetate | ND | ND | * | * |

| 1-12 | Dodecanoic acid ethyl ester | ND | ND | ND | ** |

| 1-13 | Benzenepropanoic acid ethyl ester | - | * | ** | * |

| 1-14 | Tetradecanoic acid ethyl ester | ND | * | * | ** |

| 1-15 | Hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester | - | * | - | * |

| 2 | All acid compounds | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| 2-1 | Acetic acid | * | * | * | ** |

| 2-2 | Butanoic acid | * | * | * | *** |

| 2-3 | Pentanoic acid | - | - | * | * |

| 2-4 | Hexanoic acid | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| 2-5 | Octanoic acid | ND | * | ND | - |

| 3 | All alcohol compounds | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 3-1 | 1-Propanol | ND | * | * | * |

| 3-2 | 2-Methyl-1-propanol | ND | ND | * | * |

| 3-3 | 3-Methyl-1-butanol | ND | ND | ND | * |

| 3-4 | 1-Hexanol | ND | - | - | * |

| 4 | All aldehyde compounds | ** | ** | ** | *** |

| 4-1 | Acetaldehyde | ND | * | * | *** |

| 4-2 | Furfural | ND | ND | * | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Du, L.; Wang, J. Comprehensive Investigation of Grade-Specific Aroma Signatures in Nongxiangxing Baijiu Using Flavoromics Approaches. Foods 2025, 14, 3781. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213781

Sun Y, Zhang H, Zhang H, Huang J, Du L, Wang J. Comprehensive Investigation of Grade-Specific Aroma Signatures in Nongxiangxing Baijiu Using Flavoromics Approaches. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3781. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213781

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yangyang, Heyun Zhang, Huan Zhang, Jihong Huang, Liping Du, and Juan Wang. 2025. "Comprehensive Investigation of Grade-Specific Aroma Signatures in Nongxiangxing Baijiu Using Flavoromics Approaches" Foods 14, no. 21: 3781. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213781

APA StyleSun, Y., Zhang, H., Zhang, H., Huang, J., Du, L., & Wang, J. (2025). Comprehensive Investigation of Grade-Specific Aroma Signatures in Nongxiangxing Baijiu Using Flavoromics Approaches. Foods, 14(21), 3781. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213781