What Do Turkish Parents Think About Using Bee Products for Their Children?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Study Group

2.3. Data Collection Tools

- (1)

- What do you do to protect your child or children from diseases?

- (2)

- Do you consume bee products for your child or children? If yes, which bee products do you prefer?

- (3)

- Which bee product do you use and for what purpose or purposes?

- (4)

- What do you pay attention to when choosing bee products for your child or children?

- (5)

- Do you face any difficulties in getting your child or children to consume bee products? If yes, what are the difficulties you face? How do you overcome these difficulties?

- (6)

- Where do you obtain bee products?

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

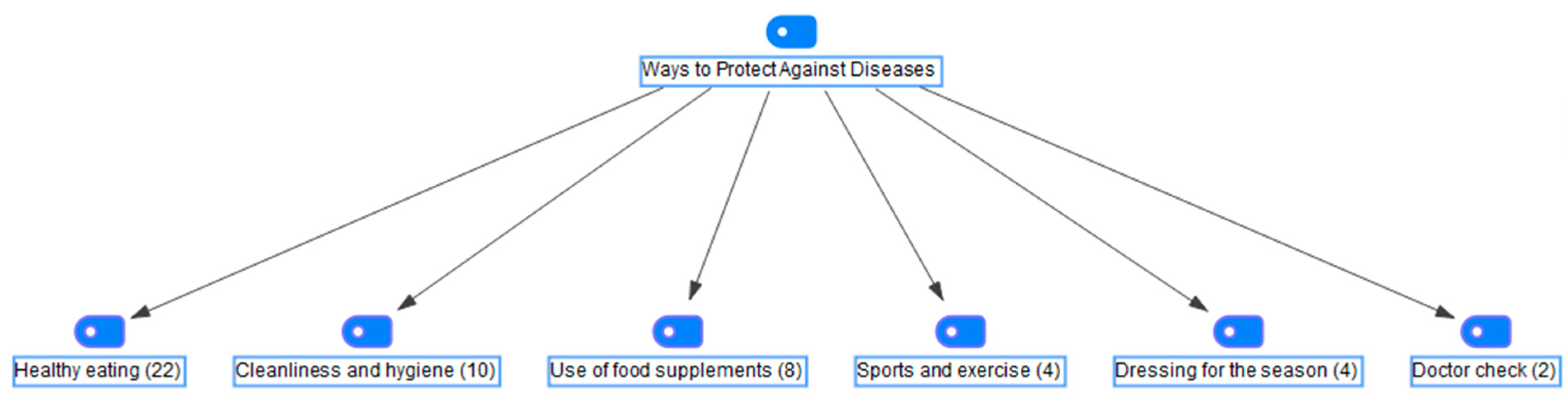

3.1. Protecting Their Children from Diseases

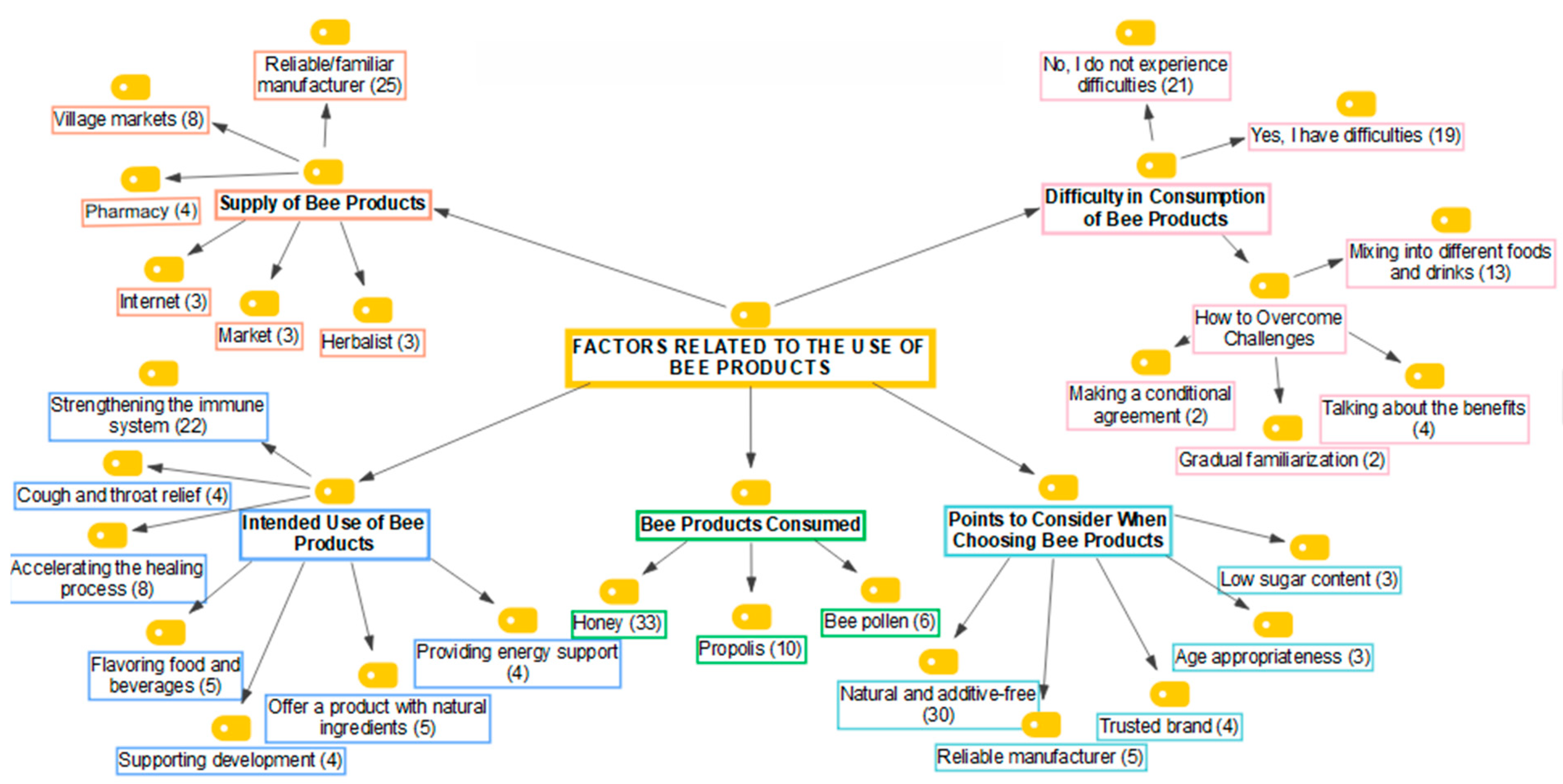

3.2. Aspects of Parents’ Use of Bee Products for Their Children

4. Discussion

- The participants of the study were limited to parents who have a child/children between the ages of 4–6 and live in the city center.

- The parents who make up the study group were not kept equal in terms of being a mother or a father.

- Since a purposeful sampling method was used in the study, although in-depth data on the subject were obtained, the findings could not be directly generalized to large masses due to the limitations of the sample.

- The fact that the answers given by the parents to the interview questions were based on self-reports.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinto, J.; Ximenes, Z.C.; Jesus, A.; Leite, A.R.J.; Noronha, H. The Role of Nutrition in Children’s Growth and Development at Early Age: Systematic Review. Int. J. Res. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, F.; Montserrat-De la Paz, S.; Leon, M.J.; Rivero-Pino, F. Effects of malnutrition on the immune system and infection and the role of nutritional strategies regarding improvements in children’s health status: A literature review. Nutrients 2023, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Igwe, V.S.; Amagwula, I.O. Nutritional diseases and nutrient toxicities: A systematic review of the diets and nutrition for prevention and treatment. Int. J. Adv. Acad. Res. 2020, 6, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytop, Y.; Akbay, C.; Meral, H. Consumers behavior towards bee products consumption in the centre district of Kahramanmaras Province. Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Tarım Ve Doğa Derg. 2019, 22, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarello, G.; Pinto, A.; Crovato, S.; Tiozzo Pezzoli, B.; Pietropaoli, M.; Bertola, M.; Formato, G. Consumers’ perceptions and behaviors regarding honey purchases and expectations on traceability and sustainability in Italy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waykar, B.; Alqadhi, Y.A. Beekeeping and bee products; Boon for human health and wealth. Indian J. Pharm. Biol. Res. 2016, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basa, B.; Belay, W.; Tilahun, A.; Teshale, A. Review on medicinal value of honeybee products: Apitherapy. Adv. Biol. Res. 2016, 10, 236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lanting, C.I.; Van Wouwe, J.P.; Reijneveld, S.A. Infant milk feeding practices in The Netherlands and associated factors. Acta Paediatr. 2005, 94, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, M.Z.; Sharma, J. Honey and its beneficial therapeutic effects: A review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.S.; Bhowmik, D.; Biswajit, C.; Chandira, M.R. Medicinal uses and health benefits of honey: An overview. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2010, 2, 385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, B. Viral upper respiratory infection. In Integrative Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, F.; Zanvit, A.; Colombo, M. Role of a proprietary propolis-based product on the wait-and-see approach in acute otitis media and in preventing evolution to tracheitis, bronchitis, or rhinosinusitis from nonstreptococcal pharyngitis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2016, 9, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salatino, A. Perspectives for uses of propolis in therapy against infectious diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshallash, K.S.; Abolaban, G.; Elhamamsy, S.M.; Zaghlool, A.; Nasr, A.; Nagib, A.; Taha, I.M. Bee pollen as a functional product–Chemical constituents and nutritional properties. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolayli, S.; Keskin, M. Natural bee products and their apitherapeutic applications. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2020, 66, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghouizi, A.; Bakour, M.; Laaroussi, H.; Ousaaid, D.; El Menyiy, N.; Hano, C.; Lyoussi, B. Bee pollen as functional food: Insights into its composition and therapeutic properties. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yin, P.; Yu, L.; Tian, F.; Chen, W.; Zhai, Q. Effects of early diet on the prevalence of allergic disease in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İkiz, S.; Keskin, M. Bee products as a food supplement in childhood nutrition and health. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2024, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyürek, A.; Begde, Z.; Özkan, İ. Okul öncesi dönem çocukların beslenmesi konusunda ebeveyn görüşlerinin belirlenmesi. Uluslararası Hakemli Beşeri Ve Akad. Bilim. Derg. 2013, 2, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Health Promot. Pract. 2015, 16, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyimbili, F.; Nyimbili, L. Types of Purposive Sampling Techniques with Their Examples and Application in Qualitative Research Studies. Br. J. Multidiscip. Adv. Stud. 2024, 5, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. How was it for you? The Interview Society and the irresistible rise of the (poorly analyzed) interview. Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisko, J.W.; Maschi, T. Content Analysis. Pocket Guides to Social Work Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zuzak, T.J.; Boňková, J.; Careddu, D.; Garami, M.; Hadjipanayis, A.; Jazbec, J.; Längler, A. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by children in Europe: Published data and expert perspectives. Complement. Ther. Med. 2013, 21, S34–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marimuthu, M. Young mothers’ acceptance of herbal food supplements: Centred on preventive health behaviour for children. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.W. Trends in Korean parents’ perceptions on food additives during the period 2014–2018. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piekara, A.; Krzywonos, M.; Kaczmarczyk, M. What do Polish parents and caregivers think of dietary supplements for children aged 3–12? Nutrients 2020, 12, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seçilmiş, Y.; Silici, S. Bee product efficacy in children with upper respiratory tract infections. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2020, 62, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaževič, T.; Jazbec, J. A double blind randomised placebo controlled study of propolis (bee glue) effectiveness in the treatment of severe oral mucositis in chemotherapy treated children. Complement. Ther. Med. 2013, 21, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, C.; Alberti, I.; Parri, N.; Agostoni, C.V.; Bettocchi, S.; Zampogna, S.; Milani, G.P. Phytotherapeutic, Homeopathic Interventions and Bee Products for Pediatric Infections: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Muñoz, M.F.; Bartolome, B.; Caminoa, M.; Bobolea, I.; Ara, M.G.; Quirce, S. Bee pollen: A dangerous food for allergic children. Identification of responsible allergens. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2010, 38, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, S.; Akyol, S. The consumption of propolis and royal jelly in preventing upper respiratory tract infections and as dietary supplementation in children. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 5, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Živanović, S.; Pavlović, D.; Stojanović, N.; Veljković, M. Attitudes to and prevalence of bee product usage in pediatric pulmonology patients. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, V.; Šarčević, D.; Glišić, M. Dietary habits of Serbian preschool and school children with regard to food of animal origin. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 59th International Meat Industry Conference MEATCON2017, Zlatibor, Serbia, 1–4 October 2017; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; Volume 85, p. 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | N | Categories | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 26 | Employment Status | Working | 25 |

| Male | 14 | Not working | 15 | ||

| Age | 20–29 years | 2 | Family structure | Nuclear family | 34 |

| 30–39 years | 25 | Extended family | 4 | ||

| 40–49 years | 8 | Single parent | 2 | ||

| Educational attainment | Primary and secondary school | 1 | Total number of children in the family | Only child | 16 |

| High school | 7 | Two children | 18 | ||

| Undergraduate degree | 25 | Three children | 6 | ||

| Postgraduate | 11 | Total monthly income of your family | 40,000 TL–60,000 TL | 12 | |

| More than 60,000 TL | 28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

İkiz, S.; Keskin, M.; Gürsoy, F. What Do Turkish Parents Think About Using Bee Products for Their Children? Foods 2025, 14, 3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203532

İkiz S, Keskin M, Gürsoy F. What Do Turkish Parents Think About Using Bee Products for Their Children? Foods. 2025; 14(20):3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203532

Chicago/Turabian Styleİkiz, Selin, Merve Keskin, and Figen Gürsoy. 2025. "What Do Turkish Parents Think About Using Bee Products for Their Children?" Foods 14, no. 20: 3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203532

APA Styleİkiz, S., Keskin, M., & Gürsoy, F. (2025). What Do Turkish Parents Think About Using Bee Products for Their Children? Foods, 14(20), 3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203532