Competitive Advantage in the World of Wine—An Analysis of Differentiation Strategies Developed by Sectoral Brands in the Global Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Competitive Advantage

2.2. Differentiation

2.3. Sectoral Brands

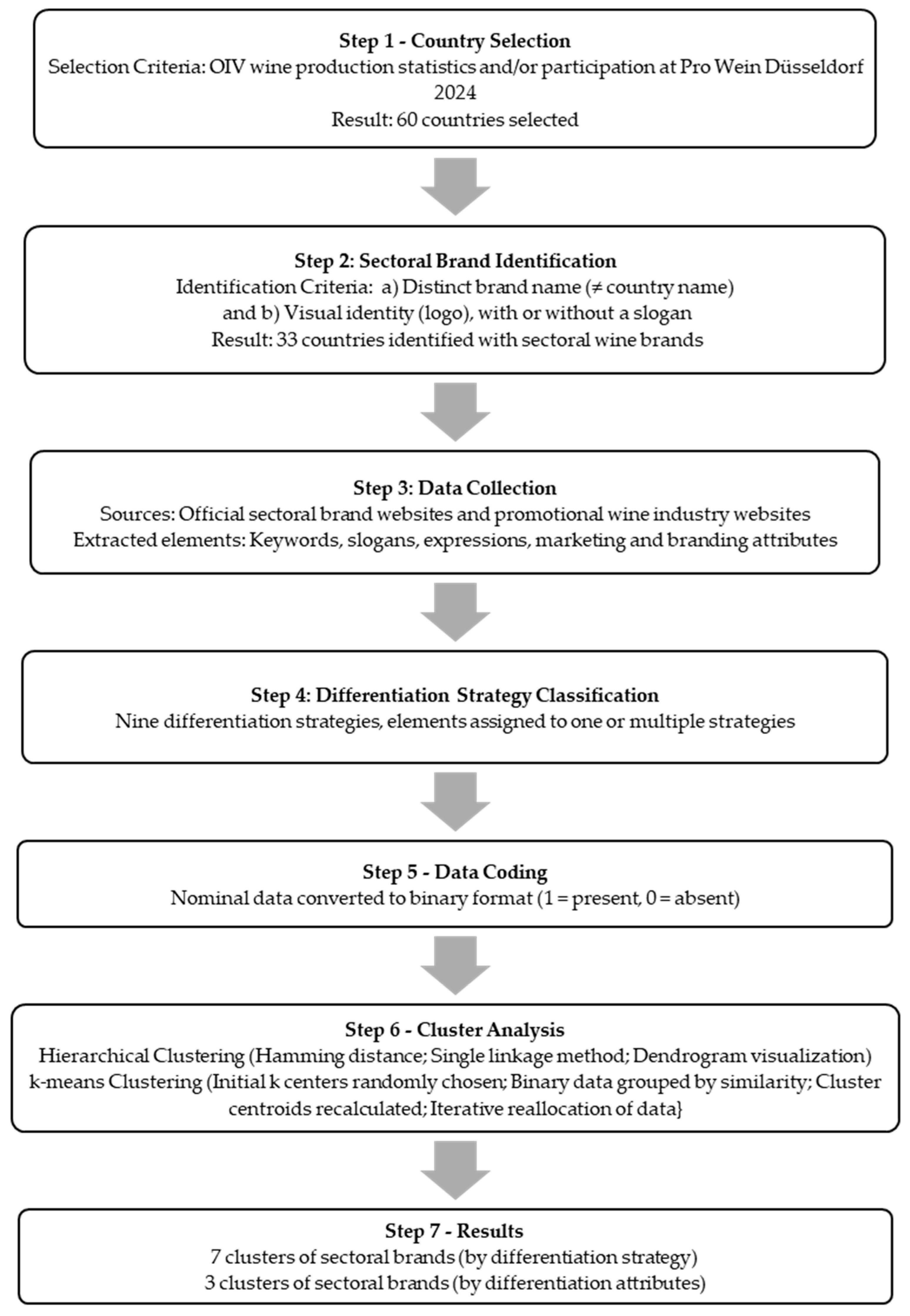

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

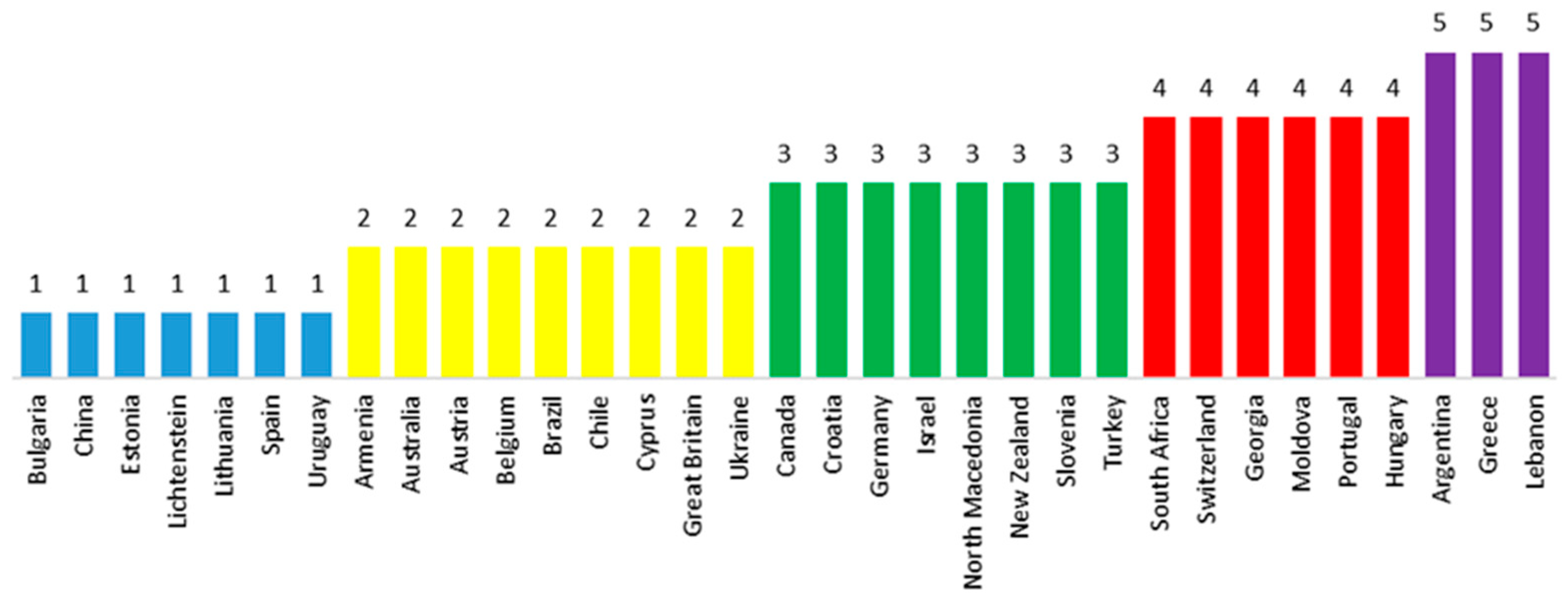

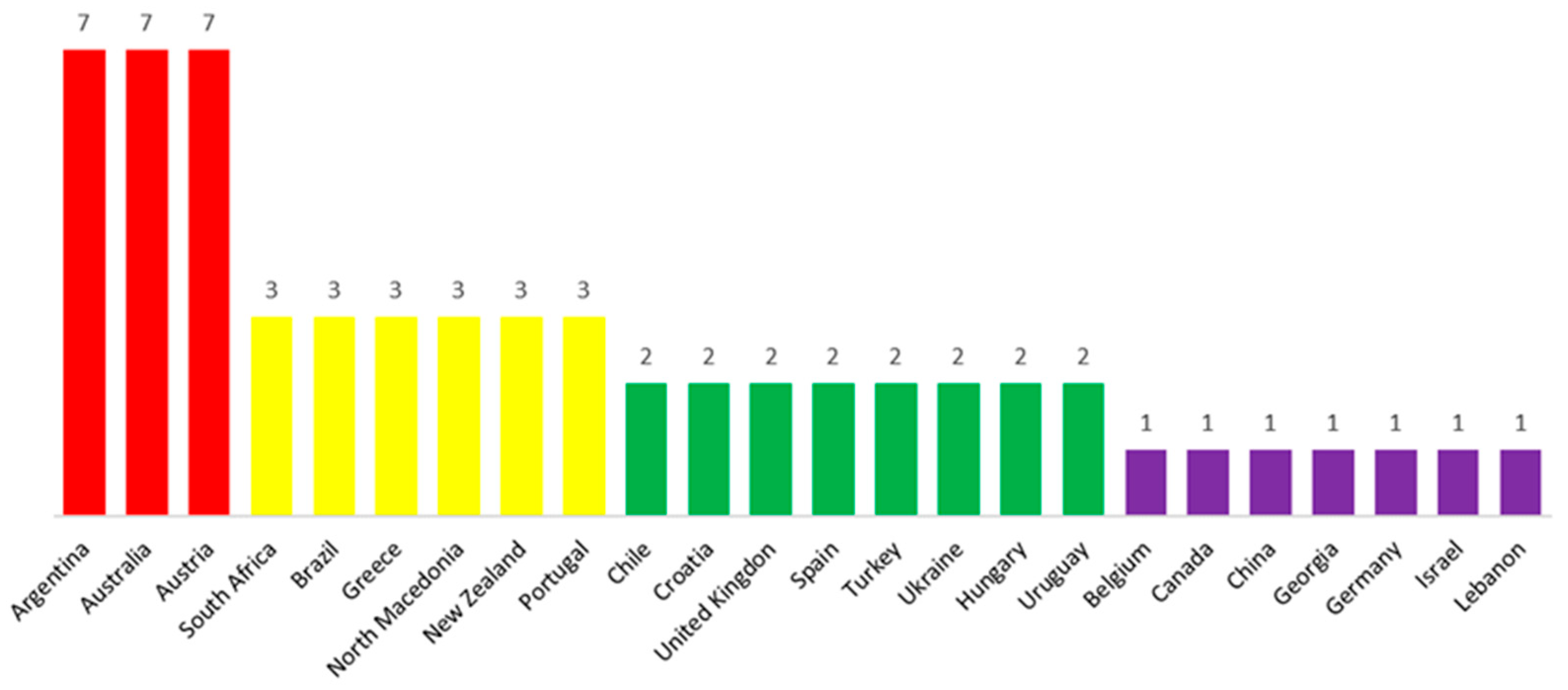

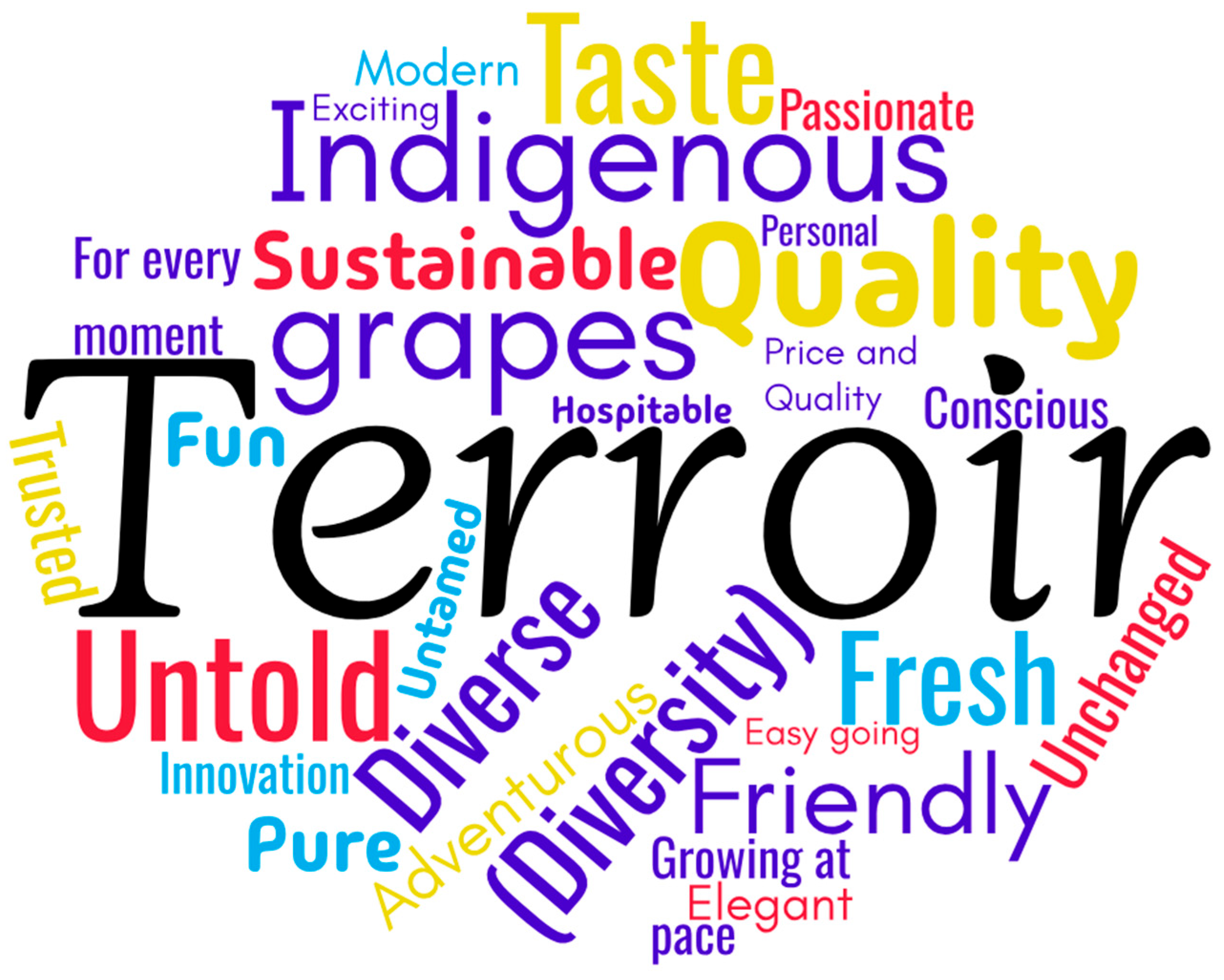

4.1. Differentiation Strategies and Attributes Allocation

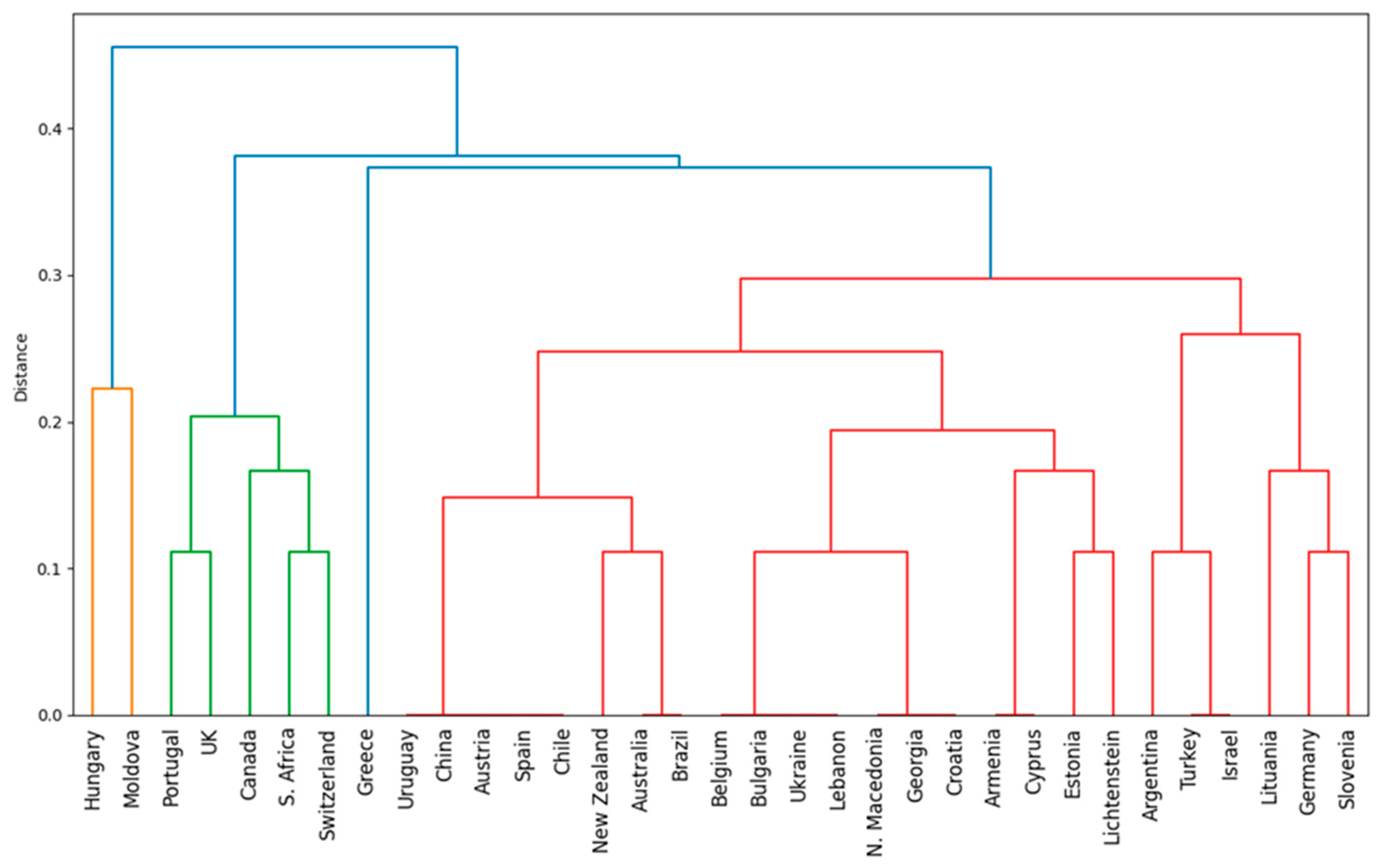

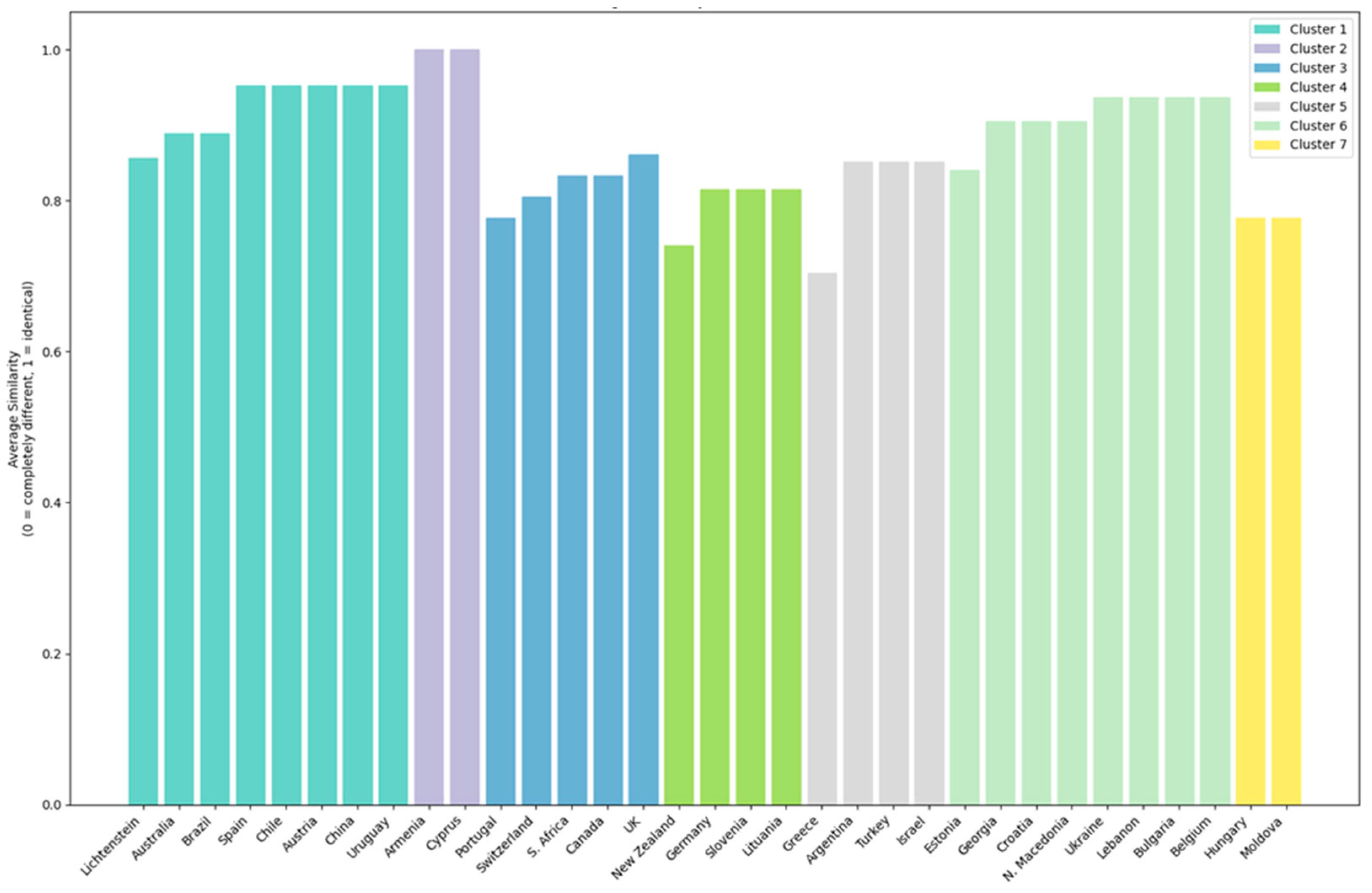

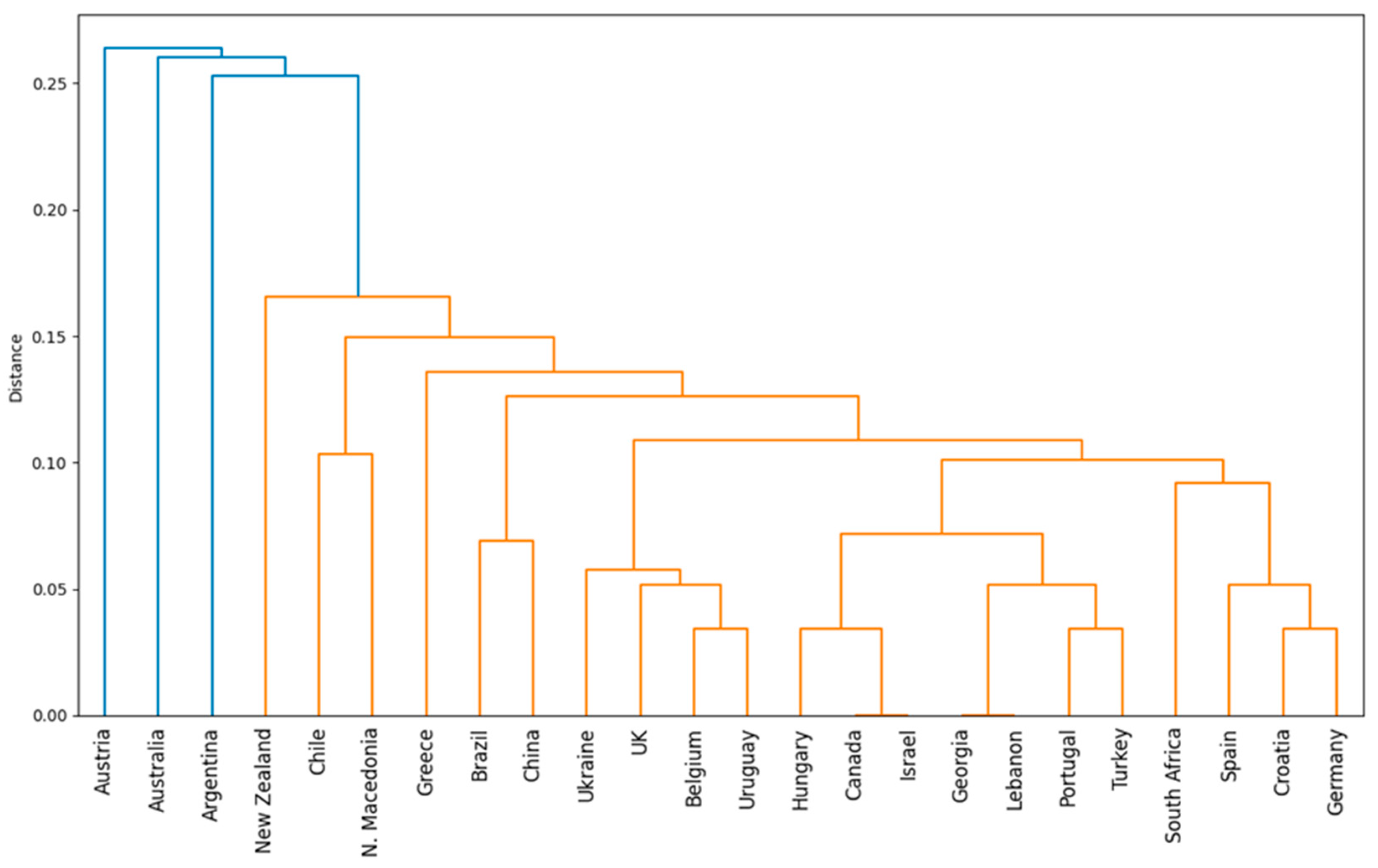

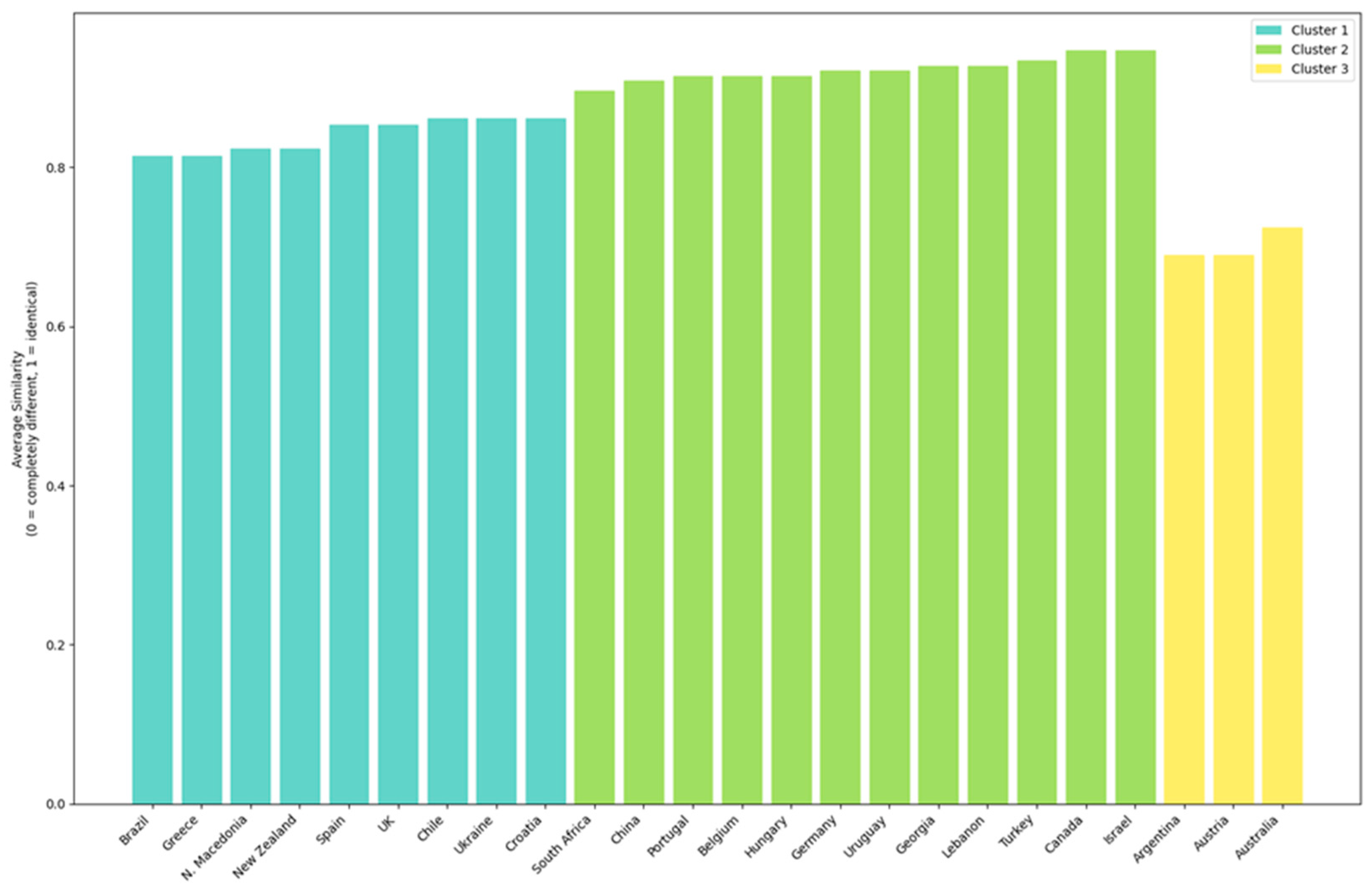

4.2. Clusters Based on Differentiation Strategies and Attributes

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Attribute from the Official Wine Brand Websites and Other Alternative Websites | Leadership | How it is Made | Tradition | Heritage | Being First | Being Latest | Specialist | Preference of a Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | (1) Diversity (2) For every moment https://interprofesionaldelvino.es/ (accessed on 14 November 2024). | ||||||||

| Chile | (1) Purity (Untamed) https://www.winesofchile.org/ (accessed on 12 November 2024). | “Wine of Chile—Wine is in our nature”—slogan | |||||||

| Australia | (1) Adventurous by nature (2) Friendly (3) Conscious (4) Ancient lands (5) Sustainable (6) Quality (7) Trusted https://www.wineaustralia.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2024). | Modern thinking | |||||||

| South Africa | (1) Welcome to our world of discovery—slogan, (2) A magical place, (3) Friendly people https://www.wosa.co.za/ (accessed on 14 November 2024). | Leaders in production integrity (from soil to glass) | A proud heritage—over 360 years of winemaking | A first-choice COO the next time a decision is made about what wine to enjoy. | |||||

| Argentina | (1) Argentina’s got range—slogan (2) Elegant (3) Friendly people (4) Fun (5) Passionate (6) Sustainable, (7) Altitude and latitude https://winesofargentina.org/ (accessed on 14 November 2024). | 3D winemaking | An old producer in the New World | An extensive viticulture heritage | Innovation|Research|Digitization|Experimentation|Micro-terroirs|Parceling|GIs|Evolution| | ||||

| Germany | (1) Diversity https://winesofgermany.co.uk/ (accessed on 12 November 2024). | The style of German wines (harmoniously, dry, rich, ripe, fruitiness) | 2000 years of viticulture tradition | ||||||

| Portugal | (1) A world of difference—slogan (2) Portugal stands out for their wealth of grape varieties (3) From hot and dry to humid and cold climates, Portugal manages to produce many different styles of wines https://www.viniportugal.pt (accessed on 12 November 2024). | Portugal is the European country with the greatest diversity of grape varieties per square kilometer | Ancient wisdom | Knowledge of its people | |||||

| New Zealand | Altogether unique—slogan, The 3 Pillars New Zealand Wine Brand Essence: (1) Purity (2) Innovation (3) Care https://www.nzwine.com (accessed on 13 November 2024). | Care | Innovation | ||||||

| Brazil | Get ready for something (1) New (fresh) (2) Something fun (3) Something surprising (friendly). https://www.winesofbrazil.com.br (accessed on 12 November 2024). | New | |||||||

| Hungary | (1) Personally (2) Terroir https://winesofhungary.hu (accessed on 13 November 2024). | Legends | Personally—related to Hungarian winemaker (person) | Personally—related to consumer | |||||

| Austria | The DNA of the Austrian wine: (1) Excellent (2) Natural (3) Hospitable (4) Easy going (5) Quality (6) Fresh (7) Terroir https://www.oesterreichwein.at (accessed on 11 November 2024). | The art of wine. Down to earth | |||||||

| Georgia | (1) More than 525 indigenous grape varieties https://winesgeorgia.com (accessed on 12 November 2024). | The cradle of wine | The cradle of wine | 8000 vintages | |||||

| Moldova | https://wineofmoldova.com/ro/ (accessed on 13 November 2024). | The largest cellars in the world | A legend alive, supported by legends that everyone can embrace | Our wine has been crafted by generations of winemakers | Appreciated by consumers in both the East and West | ||||

| Greece | (1) Modern, (2) Diverse terroir, (3) Excellent value https://winesofgreece.org (accessed on 13 November 2024). | Diverse terroir | Eternally | Heritage | The hand of the Winemaker | ||||

| Switzerland | (1) The smallest of the great wine regions https://www.swisswine.ch/en/media (accessed on 14 November 2024). | The smallest of the great wine regions | Of course. Naturally | Of course. Naturally | |||||

| UK | (1) Highest quality, (2) Growing at pace https://winegb.co.uk (accessed on 13 November 2024). | A desire to curate the next world wine market | Growing at pace | ||||||

| Canada | (1) Cool climate region, providing ideal growing conditions where grapes ripen slowly and uniformly https://winesofcanada.ca https://winecountryontario.ca (accessed on 12 November 2024). | Leadership in sustainable practices | (1) Canada is renowned for its premium ice wine, (2) grapes ripen slowly and uniformly | ||||||

| Armenia | https://vwfa.am (accessed on 11 November 2024). | 6100-year-old tradition in winemaking | The sacred land of wine | ||||||

| Croatia | (1) Diversity—vina mosaica (2) Taste the place!—slogan https://vinacroatia.hr (accessed on 12/11/2024). | tradition | heritage | ||||||

| North Macedonia | (1) Untamed (2) Untold (3) Unchanged https://tikves.com.mk (accessed on 13 November 2024). | untamed, untold, unchanged | untamed, untold, unchanged | ||||||

| Ukraine | (1) The taste of Ukraine, (2) Emphasize on quality https://vino.ua/ua/ukraina/ (accessed on 11 November 2024). | History | |||||||

| Slovenia | https://www.wineslovenia.com (accessed on 14 November 2024). | Discover a world of artisanal winemaking | Discover a world of artisanal winemaking | Discover a world of artisanal winemaking | |||||

| Turkey | Bringing out the potential of (1) indigenous varieties and (2) terroir https://www.decanter.com/wine/turkey-wine-lands-on-the-rise-535193 (accessed on 12 November 2024). | A new path—Bringing out the potential of indigenous varieties and terroirs | Bringing out the potential of indigenous varieties and terroirs | ||||||

| Israel | (1) From the highlands to the desert—slogan https://www.winesofisrael.info (accessed on 13 November 2024). | From the highlands to the desert—slogan | Bible tradition | ||||||

| Lebanon | (1) Indigenous grapes https://www.lebanonwines.com (accessed on 11 November 2024). | 7000 years of wine production | wine heritage | First wine merchants | Generations of experience | ||||

| Bulgaria | https://www.bulgarianwine.net (accessed on 14 November 2024). | From Ancient Thrace to Modern Days—slogan | |||||||

| Estonia | https://visitestonia.com (accessed on 11 November 2024). | Estonian wines are often made from fruits and berries besides grapes. | |||||||

| Lithuania | https://vynoklubas.lt/wine https://lithuania.travel (accessed on 13 November 2024). | Lithuanian wines are often made from fruits and berries besides grapes. | |||||||

| Lichtenstein | https://tourismus.li (accessed on 14 November 2024). | 2000 years of tradition | |||||||

| Belgium | (1) Quality https://wob.belgischewijnbouwers.be (accessed on 12 November 2024). | Artisanal approach | |||||||

| China | A refreshing encounter https://www.decanter.com/wine-news/china-to-become-leading-wine-producer-82458/2024 (accessed on 13 November 2024). | ||||||||

| Cyprus | https://winecyprus-naturally.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2024). | A journey of life made of wine | A journey of life made of wine | ||||||

| Uruguay | (1) Atlantic wines from South America to the world. A small country with (2) big wines https://uruguay.wine/en/ (accessed on 12 November 2024). |

References

- Mueller Loose, S.; del Rey, R. State of the International Wine Markets in 2023. The wine market at a crossroads: Temporary or structural challenges? Wine Econ. Policy 2024, 13, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- EU Wine Market Observatory. Prospectus of the EU Wine Sector. 2024. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/document/download/83588b14-0c75-43a4-b8ab-c5718bee6b01_en?filename=future-prospects-of-the-eu-wine-sector-june-2024.pdf&prefLang=hu (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- International Organization of Vine and Wine. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/2024-04/2024_OIV_April_PressConference_PPT.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Pro Wein. Available online: https://www.prowein.com/en/Media_News/Magazine/Business_Reports (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Menghini, S. The new market challenges and the strategies of the wine companies. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Will sustainability shape the future wine market? Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beber, C.L.; Lecomte, L.; Rodrigo, I.; Canali, M.; Pinto, A.S.; Pomarici, E.; Giraud-Heraud, E.; Pérès, S.; Malorgio, G. The agro-ecological challenges in the wine sector: Perceptions from European stakeholders. Wine Econ. Policy 2023, 12, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remaud, H.; Couderc, J.P. Wine business practices: A new versus old wine world perspective. Agribusiness 2006, 22, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, M. The globalization of the wine industry: New world, old world and China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2009, 1, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, P. Wine Positioning: A Handbook with 30 Case Studies of Wine Brands and Wine Regions in the World, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H.; Robinson, J. Atlasul Mondial al Vinului, 7th ed.; Litera: Bucuresti, Romania, 2015; pp. 8–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, H.; Rolaz, J.; Franco-Luesma, E.; Saenz-Navajas, M.P.; Behrens, J.; Valentin, D.; Depetris-Chauvin, N. How the country-of-origin impacts wine traders’ mental representation about wines: A study in a world wine trade fair. Food Res. Int. J. 2020, 137, 109–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R. Does anyone read my papers? The gap between academic consumer research and the real (wine) world. Wine Econ. Policy 2023, 12, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R.; Loose, S. State of the International Wine Market in 2022: New market trends for wines require new strategies. Wine Econ. Policy 2023, 12, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. Competitive Strategy. Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, 2nd ed.; Simon & Schuster Export Ed.: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.M. Contemporary Strategy Analysis, 10th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 155–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Theories for competitive advantage. In Being Practical with Theory: A Window into Business Research, 1st ed.; Hasan, H., Ed.; Lulu.com: Wollongong, Australia, 2014; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, H.; Senturk, H.A.; Tatoglu, E.; Golgeci, I.; Kalaycioglu, O.; Etlioglu, T. The Simultaneous Effect of Firm Capabilities and Competitive Strategies on Export Performance: The Role of Competitive Advantages and Competitive Intensity. Int. Mark. Rev. 2021, 38, 1242–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongkol, K. A comparative study of a single competitive strategy and a combination approach for enterprise performance. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 23, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. The Value of Consistency: Portfolio Labelling Strategies and Impact on Winery Brand Equity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, T. Marketing success through differentiation of anything. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1980, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, T. The Economics of the Brand: A Marketing Analysis; McGraw Hill: London, UK, 1986; pp. 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, D. New Economy Excellence Series, New Economy Expression: Redefining Marketing in the Multichannel Age, 1st ed.; Wiley Blackwell: London, UK, 2001; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management Global Edition, 15th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2016; pp. 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Munteanu, C.C. Competitive differentiation through brand extensions in the era of hyper competition. Rom. Econ. J. 2015, 18, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, J.; Brady, M. Capabilities, strategies and firm performance in the United Kingdom. J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.; Moen, O.; Madsen, T.K. Antecedents to differentiation strategy in the exporting SME. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N.F.; Simões, V.C.; Fontes, M. Competitive strategies and international new ventures’ performance: Exploring the moderating effects of internationalization duration and preparation. Bus. Res. Q. 2020, 23, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, A.; Trout, J. Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Urde, M.; Koch, C. Market and brand-oriented schools of positioning. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2014, 23, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, B.; Dawes, J. What is Differentiation and How Does it Work? J. Mark. Manag. 2001, 17, 739–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J. Strategy. Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, 3rd ed.; Cooper, C.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; Volume 12, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Trout, J.; Rivkin, S. Differentiate or Die. Survival in Our Era of Killer Competition, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, J. Marketing capability, organizational adaptation and new product development performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 49, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, E. Wine Brands—Success Strategies for New Markets, New Consumers and New Trends, 1st ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 156–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzon, J.R.F.; Rubio, M.T.M.; Garcés, S.A. The competitive advantage in business, capabilities and strategy. What general performance factors are found in the Spanish wine industry? Wine Econ. Policy 2018, 7, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, J.D.; Valdes, R.; Hernandez, N. Chilean wine in the European market. A positioning mapping approach from Germany. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Agrar. UN Cuyo 2015, 47, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Bandieri, L.; Castellini, A. The competitiveness of Romagna wineries. An exploratory analysis of the impact of different strategic approaches on business performance. Wine Econ. Policy 2023, 12, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.; White, L.; Frost, W. Wine and Identity—Branding, Heritage, Terroir, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Reaching for Customer Centricity—Wine Brand Positioning Configurations. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Marketing Association. What Is a Brand? Available online: https://www.ama.org/topics/branding/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Stanton, W.; Etzel, M.; Walker, B. Fundamentos de Marketing, 11th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 248–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lazo, L. International brand positioning levels. Contab. Neg. 2006, 1, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pino, A.; Acevedo, O. Model for the implementation of sectoral brands: Proposal for methodological development. Iber. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. 2019, 20, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Navarro, J.; Sellers-Rubio, R. Three decades of research on wine marketing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Looking inside for competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1995, 9, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.J.; Ballington, L. Country of origin as a source of competitive advantage. J. Strateg. Mark. 2002, 10, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Competitive Identity: The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, J.C.; Chadwick, C.; Ployhart, R.E.; Golden, S.J. Making intangibles “tangible” in tests of resource-based theory: A multidisciplinary construct validation approach. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1496–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.R.; McGarry Wolf, M.; Dod, T.H. Dimensions of wine region equity and their impact on consumer preferences. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Bruwer, J. Regional brand image and perceived wine quality: The consumer perspective. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Lourenço-Gomes, L.; Pinto, L.M.C. Region of origin and perceived quality of wine: An assimilation—Contrast approach. Wine Econ. Policy 2021, 10, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passagem, N.; Crespo, C.F.; Almeida, N. The Impact of Country of Origin on Brand Equity: An Analysis of The Wine Sector. Wine Econ. Policy 2020, 9, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T.; Gray, E.R. Corporate brands: What are they? What of them? Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 972–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schamel, G. Dynamic Analysis of Brand and Regional Reputation: The Case of Wine. J. Wine Econ. 2009, 4, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, F.; De Rosa, M.; Trabalzi, F. Dedicated and generic marketing strategies: The disconnection between geographical indications and consumer behavior in Italy. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Spielmann, N. Characteristics of strong territorial brands: The case of champagne. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwin, C.F.; Gwin, C.R. Product Attributes Model: A Tool for Evaluating Brand Positioning. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2003, 11, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babucea, A.G. Algoritmi de Clasificare Utilizând Analiza de Cluster şi SPSS/WIN; Editura AGIR: Piteşti, Romania, 2003; pp. 409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, S.K.; Gilinsky, A., Jr.; Jordan, D. Differentiation strategies and winery financial performance: An empirical investigation. Wine Econ. Policies 2015, 4, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, F.M.; Oricain, D.N.; Martinez, R.J. Product differentiation strategy and vertical integration: An application to the DOC Rioja wine industry. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notta, O.; Vlachvei, A. Differentiation and performance in Greek wine industry. Int. J. Arts Sci. 2012, 5, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- La Sala, P.; Silvestri, R.; Contò, F. Differentiation strategies for the wine and nursery sector: Empirical evidence from an Italy region. Agric. Food Econ. 2017, 5, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B.; Hanf, J. Competitive Strategies for Wine Cooperatives in the German Wine Industry. Wine Econ. Policy 2020, 9, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.; Moschini, G. Product differentiation and the relative importance of wine attributes: U.S. retail prices. J. Wine Econ. 2022, 17, 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducman, A.A. Cultivating Connections: Crafting a Unique Identity in the Competitive Wine Market. Manag. Econ. Rev. 2023, 8, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Quici, L.; Cacchiarelli, L. The grapes in Italian wines: Assessing their value. Wine Econ. Policy 2023, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micu, D.M.; Arghiroiu, G.A.; Beciu, S. The development of a brand strategy for the Romanian wine industry: A perspective from Romanian wine exporters. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2024, 24, 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A.; Joachimsthaler, E. The Brand Relationship Spectrum. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschmann, A. Evaluating the House of Brands Strategy Using Brand Equity and Intra-Firm Loyalty. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 7, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Micu, D.M.; Beciu, S. Study on brand strategies and brand architecture in the wine industry: Case study Drăgășani vineyard, Vâlcea county, România. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2023, 23, 523–530. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Micu, D.M.; Arghiroiu, G.A.; Micu, Ș.; Beciu, S. Competitive Advantage in the World of Wine—An Analysis of Differentiation Strategies Developed by Sectoral Brands in the Global Market. Foods 2025, 14, 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111858

Micu DM, Arghiroiu GA, Micu Ș, Beciu S. Competitive Advantage in the World of Wine—An Analysis of Differentiation Strategies Developed by Sectoral Brands in the Global Market. Foods. 2025; 14(11):1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111858

Chicago/Turabian StyleMicu, Daniel Marian, Georgiana Armenița Arghiroiu, Ștefan Micu, and Silviu Beciu. 2025. "Competitive Advantage in the World of Wine—An Analysis of Differentiation Strategies Developed by Sectoral Brands in the Global Market" Foods 14, no. 11: 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111858

APA StyleMicu, D. M., Arghiroiu, G. A., Micu, Ș., & Beciu, S. (2025). Competitive Advantage in the World of Wine—An Analysis of Differentiation Strategies Developed by Sectoral Brands in the Global Market. Foods, 14(11), 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111858