Exploring the Antecedents and Consequences of Perceived Fairness in Beef Pricing: The Moderating Role of Freshness Under Conditions of Information Overload

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Organic Perception

2.2. Price Fairness

2.3. Revisit Intention

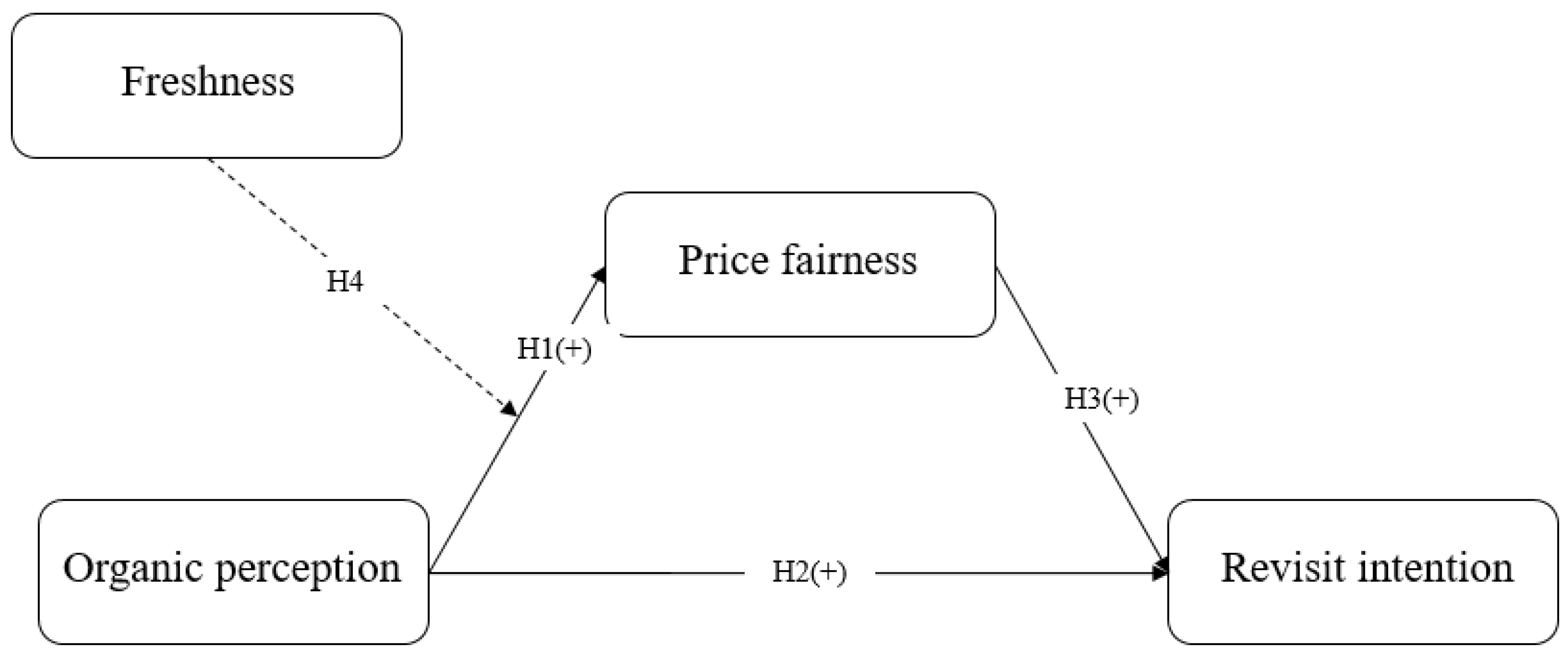

2.4. Hypotheses Development

2.5. The Moderating Effect of Freshness

3. Method

3.1. Description of Measurement Items

3.2. Recruiting Survey Participants

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Results of Validity for the Measurement Items

4.2. Correlation Matrix and Results of Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Research Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verified Market Research. Organic Beef Meat Market Valuation—2024–2031. 2024. Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/organic-beef-meat-market/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Wang, Y.; Isengildina-Massa, O.; Stewart, S. US grass-fed beef premiums. Agribusiness 2023, 39, 664–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Magistrali, A.; Butler, G.; Stergiadis, S. Nutritional benefits from fatty acids in organic and grass-fed beef. Food 2022, 11, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Lee, W.S.; Moon, J. Antecedents and consequences of healthiness in cafe service: Moderating effect of health concern. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 913291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Jabeen, F.; Tandon, A.; Sakashita, M.; Dhir, A. What drives willingness to purchase and stated buying behavior toward organic food? A Stimulus–Organism–Behavior–Consequence (SOBC) perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 125882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, B.; Rotz, C.; Thoma, G. A comprehensive environmental assessment of beef production and consumption in the United States. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.H.; Nyam-Ochir, A. The effects of fast food restaurant attributes on customer satisfaction, revisit intention, and recommendation using DINESERV scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.K.; Liu, Y.; Kang, S.; Dai, A. The role of perceived smart tourism technology experience for tourist satisfaction, happiness and revisit intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaja, G.; Yasa, N. The role of customer satisfaction in mediating the influence of price fairness and service quality on the loyalty of low cost carriers customers in Indonesia. Int. Res. J. Manag. IT Soc. Sci. 2020, 7, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Do, Q.H.; Kim, T.Y.; Wang, X. Effects of logistics service quality and price fairness on customer repurchase intention: The moderating role of cross-border e-commerce experiences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakité, Z.R.; Corson, M.S.; Brunschwig, G.; Baumont, R.; Mosnier, C. Profit stability of mixed dairy and beef production systems of the mountain area of southern Auvergne (France) in the face of price variations: Bioeconomic simulation. Agric. Syst. 2019, 171, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Guo, J. International price volatility transmission and structural change: A market connectivity analysis in the beef sector. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Lin, Y.; Gao, H.; Chen, H.; Sun, P. An overview of intelligent freshness indicator packaging for food quality and safety monitoring. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.; Ma, Y. Consumer-oriented smart dynamic detection of fresh food quality: Recent advances and future prospects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 11281–11301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakoshi, T.; Masuda, T.; Utsumi, K.; Tsubota, K.; Wada, Y. Glossiness and perishable food quality: Visual freshness judgment of fish eyes based on luminance distribution. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, C.; Pu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, L.; Cui, Z.; Zhong, Y. Recent advances in pH-responsive freshness indicators using natural food colorants to monitor food freshness. Foods 2022, 11, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Xiao, X.; Ye, H.; Ma, D.; Zhou, J. Fast visual monitoring of the freshness of beef using a smart fluorescent sensor. Food Chem. 2022, 394, 133489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips-Wren, G.; Adya, M. Decision making under stress: The role of information overload, time pressure, complexity, and uncertainty. J. Dec. Sys. 2020, 29, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, X.; Ma, L. The influences of information overload and social overload on intention to switch in social media. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrzadi, L.; Mansouri, A.; Alavi, M.; Shabani, A. Causes, consequences, and strategies to deal with information overload: A scoping review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Pirkkalainen, H.; Salo, M. Social media overload, exhaustion, and use discontinuance: Examining the effects of information overload, system feature overload, and social overload. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Kushwah, S.; Salo, J. Why do people buy organic food? The moderating role of environmental concerns and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Qalati, S.A.; Naz, S.; Rana, F. Purchase intention toward organic food among young consumers using theory of planned behavior: Role of environmental concerns and environmental awareness. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 796–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, E.; Alfinito, S.; Curvelo, I.; Hamza, K.M. Perceived value, trust and purchase intention of organic food: A study with Brazilian consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1070–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, I.; Plaza, J.; Palacios, C. The effect of grazing level and ageing time on the physicochemical and sensory characteristics of beef meat in organic and conventional production. Animals 2021, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Braghieri, A.; Piasentier, E.; Favotto, S.; Naspetti, S.; Zanoli, R. Effect of information about organic production on beef liking and consumer willingness to pay. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. Trustworthy brand signals, price fairness and organic food restaurant brand loyalty. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 3035–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prum, S.; Sovang, L.; Bunteng, L. Effects of service quality, hotel technology, and price fairness on customer loyalty mediated by customer satisfaction in hotel industry in Cambodia. Utsaha J. Entrep. 2024, 3, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiawan, I.; Jatra, I.M. The Role of Brand Image Mediate the Influence of Price Fairness on Purchase Decisions for Local Fashion Brand Products. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2022, 7, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putu, I.; Ekawati, N.W. The role of customer satisfaction and price fairness in mediating the influence of service quality on word of mouth. Am. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2020, 4, 493–499. [Google Scholar]

- Thies, A.; Altmann, B.; Countryman, A.; Smith, C.; Nair, M. Consumer willingness to pay (WTP) for beef based on color and price discounts. Meat Sci. 2024, 217, 109597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Lien, C.H.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Dong, W. Event and city image: The effect on revisit intention. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Fu, S.; Huan, T. Exploring the influence of tourists’ happiness on revisit intention in the context of Traditional Chinese Medicine cultural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimi, F.; Gabarre, S.; Rahi, S.; Al-Gasawneh, J.; Ngah, A. Modelling Muslims’ revisit intention of non-halal certified restaurants in Malaysia. J. Islam. Mark. 2022, 13, 2437–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. The influence of perceived food quality, price fairness, perceived value and satisfaction on customers’ revisit and word-of-mouth intentions towards organic food restaurants. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Gahfoor, R.Z. Satisfaction and revisit intentions at fast food restaurants. Futur. Bus. J. 2020, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sulaiti, I. Mega shopping malls technology-enabled facilities, destination image, tourists’ behavior and revisit intentions: Implications of the SOR theory. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 965642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. Price fairness, satisfaction, and trust as antecedents of purchase intentions towards organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, I.; Griffith, D.M.; Aguirre, I. Understanding the factors limiting organic consumption: The effect of marketing channel on produce price, availability, and price fairness. Org. Agric. 2021, 11, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Alok, S. Drivers of repurchase intention of organic food in India: Role of perceived consumer social responsibility, price, value, and quality. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2022, 34, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, D.; Eberle, L.; Larentis, F.; Milan, G.S. Antecedents of perceived value and repurchase intention of organic food. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Magrizos, S.; Rubel, M.; Rizomyliotis, I. Green consumerism, green perceived value, and restaurant revisit intention: Millennials’ sustainable consumption with moderating effect of green perceived quality. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2807–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, D.; Kulshreshtha, K.; Tripathi, V.; Chaturvedi, P. Does green self-identity influence the revisit intention of dissatisfied customers in green restaurants? Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023, 34, 535–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Kulshreshtha, K.; Tripathi, V.; Agnihotri, D. Investigating the impact of restaurants’ sustainable practices on consumers’ satisfaction and revisit intentions: A study on leading green restaurants. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2024, 16, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Yuen, Y.; Chong, S.C. The effects of service quality and perceived price on revisit intention of patients: The Malaysian context. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2020, 12, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hride, F.; Ferdousi, F.; Jasimuddin, S. Linking perceived price fairness, customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty: A structural equation modeling of Facebook-based e-commerce in Bangladesh. Glob. Bus. Org. Exc. 2022, 41, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A. Perceived value and behavioral intentions toward dining at Chinese restaurants in Bangladesh: The role of self-direction value and price fairness. South Asian J. Mark. 2022, 3, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Mele, M.; Lee, Y.; Islam, M. Consumer preference, quality, and safety of organic and conventional fresh fruits, vegetables, and cereals. Food 2021, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.; Antúnez, L.; Ares, G. An exploration of what freshness in fruit means to consumers. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Crang, M.; Zeng, G. Constructing freshness: The vitality of wet markets in urban China. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, D.C.; Vermeir, I.; Petrescu-Mag, R. Consumer understanding of food quality, healthiness, and environmental impact: A cross-national perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Song, X.; Gou, D.; Li, H.; Jiang, L.; Yuan, M.; Yuan, M. A polylactide based multifunctional hydrophobic film for tracking evaluation and maintaining beef freshness by an electrospinning technique. Food Chem. 2023, 428, 136784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reicks, A.; Brooks, J.; Garmyn, A.; Thompson, L.; Lyford, C.; Miller, M.F. Demographics and beef preferences affect consumer motivation for purchasing fresh beef steaks and roasts. Meat Sci. 2011, 87, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ellies-Oury, M.P.; Stoyanchev, T.; Hocquette, J. Consumer perception of beef quality and how to control, improve and predict it? Focus on eating quality. Foods 2022, 11, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlebois, S.; Hill, A.; Morrison, M.; Vezeau, J.; Music, J.; Mayhew, K. Is Buying Local Less Expensive? Debunking a Myth—Assessing the Price Competitiveness of Local Food Products in Canada. Foods 2022, 11, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, C. Is healthy eating too expensive?: How low-income parents evaluate the cost of food. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 248, 112823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, M.; Xu, Z.; Huang, H. How does information overload affect consumers’ online decision process? An event-related potentials study. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 695852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Ouyang, Z.; Liu, Y. The effect of information overload on the intention of consumers to adopt electric vehicles. Transportation 2020, 47, 2067–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, A.; AL-Hadban, W. The impact of information factors on green consumer behaviour: The moderating role of information overload. Inf. Dev. 2023, 02666669231207590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Simonetti, A.; Ruiz, C.; Kakaria, S. How online advertising competes with user-generated content in TripAdvisor. A neuroscientific approach. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelen-Blasberg, T.; Habel, J.; Klarmann, M. Automated inference of product attributes and their importance from user-generated content: Can we replace traditional market research? Int. J. Res. Mark. 2023, 40, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.A.; Moon, J. The Theory of Planned Behavior and Antecedents of Attitude toward Bee Propolis Products Using a Structural Equation Model. Foods 2024, 13, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Code | Item | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic perception | OG1 OG2 OG3 OG4 | The beef was produced in an environmentally. The beef was produced in organic manner. The beef was based on grass-fed. The beef production was eco-friendly. | Likert five-point scale 1: strongly disagree 5: strongly agree |

| Price fairness | PF1 PF2 PF3 PF4 | The price of beef was fair. The price of beef was reasonable. The price of beef was acceptable. The price of beef was affordable. | Likert five-point scale 1: strongly disagree 5: strongly agree |

| Revisit intention | RI1 RI2 RI3 | I intend to visit the place where I bought the beef again. I am going to visit the place where I purchased the beef again. I will revisit the store where I purchased the beef. | Likert five-point scale 1: strongly disagree 5: strongly agree |

| Freshness | FR1 FR2 FR3 FR4 | The color of beef was important. The freshness of beef was essential. For me, the freshness of beef was critical. Fresh visuals of beef were imperative. | Likert five-point scale 1: strongly disagree 5: strongly agree |

| Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 130 | 31.3 |

| Female | 285 | 68.7 |

| 20–29 years’ old | 60 | 14.5 |

| 30–39 years’ old | 139 | 33.5 |

| 40–49 years’ old | 146 | 35.2 |

| 50–59 years’ old | 55 | 13.3 |

| Older than 60 years’ old | 15 | 3.6 |

| Weekly eating frequency | ||

| Less than 1 time | 71 | 17.1 |

| 1–2 times | 215 | 51.8 |

| 3–6 times | 116 | 28.0 |

| Everyday | 13 | 3.1 |

| Terminal academic degree | ||

| Less than bachelor’s degree | 170 | 41.0 |

| Bachelor degree | 172 | 41.4 |

| Graduate degree | 73 | 17.6 |

| Monthly household income | ||

| Less than USD 2500 | 103 | 24.8 |

| Between USD 2500 and USD 4999 | 145 | 34.9 |

| Between USD 5000 and USD 7499 | 78 | 18.8 |

| Between USD 7500 and USD 9999 | 24 | 5.8 |

| More than USD 10,000 | 65 | 15.7 |

| Construct | Code | Loading | Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s α | Eigenvalue | Explained Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic perception | OG1 OG2 OG3 OG4 | 0.785 0.842 0.795 0.862 | 3.04 (0.97) | 0.870 | 3.135 | 20.903 |

| Price fairness | PF1 PF2 PF3 PF4 | 0.884 0.945 0.907 0.864 | 2.83 (0.99) | 0.938 | 5.624 | 37.496 |

| Revisit intention | RI1 RI2 RI3 | 0.901 0.895 0.910 | 4.33 (0.88) | 0.964 | 1.263 | 8.423 |

| Freshness | FR1 FR2 FR3 FR4 | 0.703 0.807 0.871 0.793 | 4.43 (0.74) | 0.840 | 1.868 | 12.455 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Revisit intention | 1 | |||

| 2. Price fairness | 0.219 * | 1 | ||

| 3. Freshness | 0.543 * | 0.115 * | 1 | |

| 4. Organic perception | 0.309 * | 0.375 * | 0.254 * | 1 |

| Model 1 Price Fairness | Model 2 Price Fairness | Model 3 Revisit Intention | Model 4 Revisit Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (t value) | β (t value) | β (t value) | β (t value) | |

| Constant | −0.033 (−0.05) | −0.022 (−0.03) | 3.310 (21.56) * | 3.067 (15.20) * |

| Organic perception | 1.070 (4.57) * | 1.066 (4.51) * | 0.237 (5.25) * | 0.247 (5.45) * |

| Freshness | 0.393 (2.87) * | 0.391 (2.85) * | ||

| Interaction | −0.156 (−3.03) * | −0.155 (−2.98) * | ||

| Price fairness | 0.106 (2.39) * | 0.106 (2.39) * | ||

| Gender | 0.037 (0.38) | 0.183 (2.06) * | ||

| Age | −0.012 (−0.26) | 0.035 (0.86) | ||

| F-value | 26.05 * | 15.60 * | 24.87 * | 13.81 * |

| R2 | 0.1598 | 0.1602 | 0.1077 | 0.1188 |

| Conditional effect of focal predictor | ||||

| Freshness | ||||

| 4.00 | 0.445 (8.43) * | 0.445 (8.34) * | ||

| 4.75 | 0.327 (6.52) * | 0.329 (6.51) * | ||

| 5.00 | 0.288 (5.18) * | 0.290 (5.18) * | ||

| Index of mediated moderation | Index | Index | ||

| −0.0167 * | −0.0165 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, K.-A.; Moon, J. Exploring the Antecedents and Consequences of Perceived Fairness in Beef Pricing: The Moderating Role of Freshness Under Conditions of Information Overload. Foods 2025, 14, 1844. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111844

Sun K-A, Moon J. Exploring the Antecedents and Consequences of Perceived Fairness in Beef Pricing: The Moderating Role of Freshness Under Conditions of Information Overload. Foods. 2025; 14(11):1844. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111844

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Kyung-A, and Joonho Moon. 2025. "Exploring the Antecedents and Consequences of Perceived Fairness in Beef Pricing: The Moderating Role of Freshness Under Conditions of Information Overload" Foods 14, no. 11: 1844. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111844

APA StyleSun, K.-A., & Moon, J. (2025). Exploring the Antecedents and Consequences of Perceived Fairness in Beef Pricing: The Moderating Role of Freshness Under Conditions of Information Overload. Foods, 14(11), 1844. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111844