A Sorting Task with Emojis to Understand Children’s Recipe Acceptance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Samples

2.3. Procedure: Sorting Task

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ; [11]) and seven paper clips were given to each participant inside an envelope. Participants were instructed to label the envelope with their age and gender (no additional information) and (1st) spread the emojis in their table, (2nd) look at the photos one by one, and group them under the emoji they considered better expressed their opinion about the dish presented in the image (not the appearance, but imagining eating the whole dish), and (3rd) clip the corresponding emoji with the photos, put them inside the envelope, and return it to the researcher. Each recipe was assigned to a single emoji, ensuring a one-to-one correspondence between recipes and emotional responses. Because emojis were the grouping factor, participants could create up to seven groups, but using all emojis was optional. Therefore, the number of groups created by each participant was variable.

; [11]) and seven paper clips were given to each participant inside an envelope. Participants were instructed to label the envelope with their age and gender (no additional information) and (1st) spread the emojis in their table, (2nd) look at the photos one by one, and group them under the emoji they considered better expressed their opinion about the dish presented in the image (not the appearance, but imagining eating the whole dish), and (3rd) clip the corresponding emoji with the photos, put them inside the envelope, and return it to the researcher. Each recipe was assigned to a single emoji, ensuring a one-to-one correspondence between recipes and emotional responses. Because emojis were the grouping factor, participants could create up to seven groups, but using all emojis was optional. Therefore, the number of groups created by each participant was variable.2.4. Data Analysis

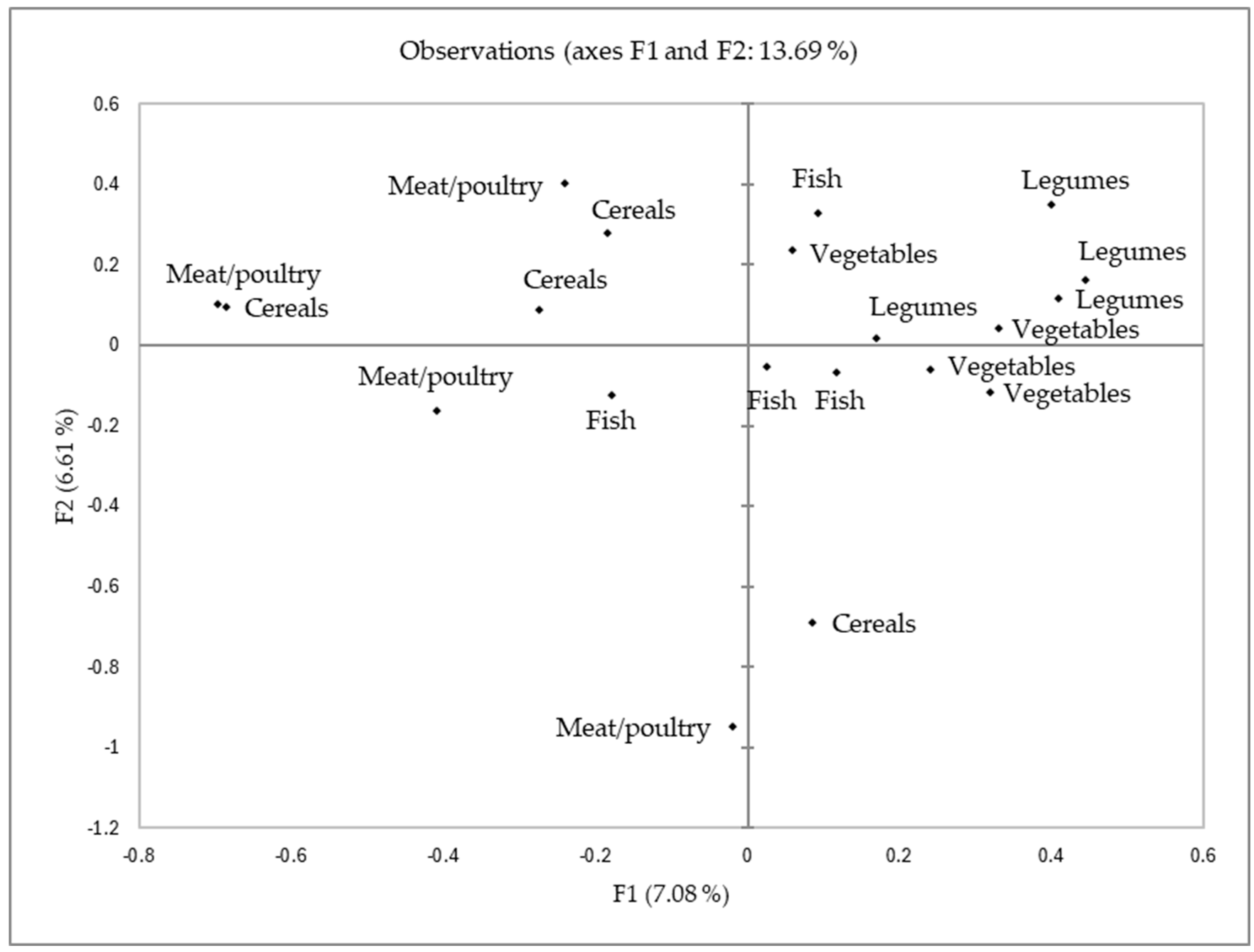

3. Results

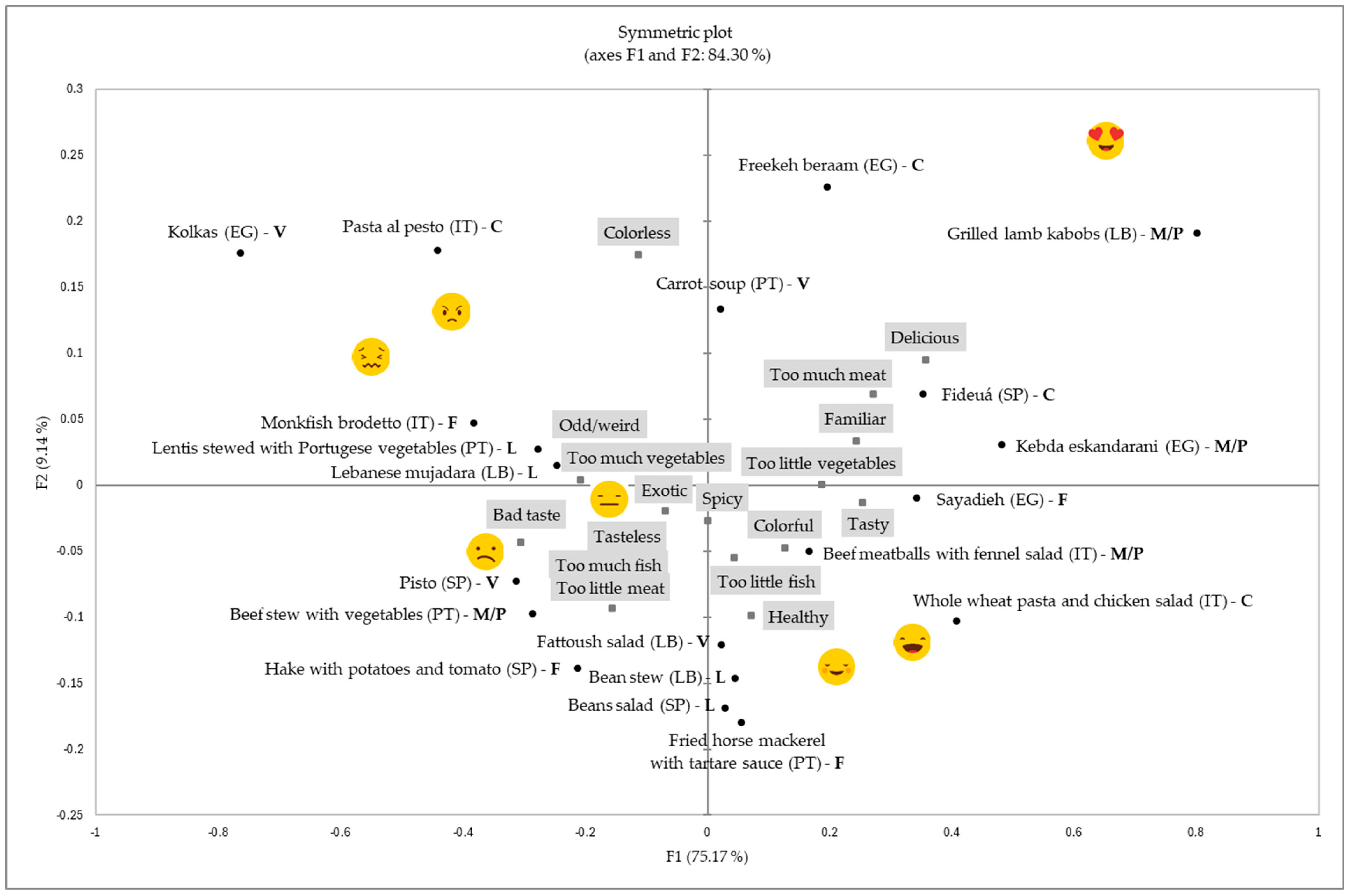

and

and  , concepts such as “healthy”, “too little fish”, and “tasty” under the emojis

, concepts such as “healthy”, “too little fish”, and “tasty” under the emojis  and

and  , and concepts such as “too much meat”, “familiar”, and “delicious” with the recipes grouped under the

, and concepts such as “too much meat”, “familiar”, and “delicious” with the recipes grouped under the  emoji. In addition, the concepts “too little vegetables” and “tasty” seemed to be linked to positive emojis. These responses suggested that children had a positive predisposition about healthy options, although a negative emotional response to “too much vegetables”.

emoji. In addition, the concepts “too little vegetables” and “tasty” seemed to be linked to positive emojis. These responses suggested that children had a positive predisposition about healthy options, although a negative emotional response to “too much vegetables”.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costell, E.; Tárrega, A.; Bayarri, S. Food acceptance: The role of consumer perception and attitudes. Chemosens. Percept. 2010, 3, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blissett, J.; Fogel, A. Intrinsic and extrinsic influences on children’s acceptance of new foods. Physiol. Behav. 2013, 121, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, K.E.; Swaney-Stueve, M.; Chambers, D.H. A focus group approach to understanding food-related emotions with children using words and emojis. J. Sens. Stud. 2017, 32, e12264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, S.A.; Batista, S.A.; da Costa Maynard, D.; Ginani, V.C.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Botelho, R.B.A. Acceptability of school menus: A systematic review of assessment methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, S.; Kane-Potaka, J.; Tsusaka, T.W.; Tripathi, D.; Upadhyay, S.; Kavishwar, A.; Jalagam, A.; Sharma, N.; Nedumaran, S. Acceptance and impact of millet-based mid-day meal on the nutritional status of adolescent school going children in a peri urban region of Karnataka State in India. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Spigno, G.; Fumi, M.D.; Porretta, S. School lunch acceptance in pre-schoolers. Liking of meals, individual meal components and quantification of leftovers for vegetable and fish dishes in a real eating situation in Italy. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 28, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Brito de Oliveira, M.; do Carmo, C.N.; da Silva Menezes, E.M.; Tavares Colares, L.G.; Gonçalves Ribeiro, B. Acceptance evaluation of school meals through different method approaches by children in Brazil. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanabria, M.C.; Frutos, D.; Preda, J.; Gónzalez Céspedes, L.; Cornelli, P. Adecuación y aceptación de almuerzos escolares en dos escuelas públicas de Asunción. Pediatría 2017, 44, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Sick, J.; Monteleone, E.; Pierguidi, L.; Ares, G.; Spinelli, S. The meaning of emoji to describe food experiences in pre-adolescents. Foods 2020, 9, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouteten, J.J.; Verwaeren, J.; Lagast, S.; Gellynck, X.; De Steur, H. Emoji as a tool for measuring children’s emotions when tasting food. Food Qual. Pref. 2018, 68, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaney-Stueve, M.; Jepsen, T.; Deubler, G. The emoji scale: A facial scale for the 21st century. Food Qual. Pref. 2018, 68, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, K.E.; Swaney-Stueve, M.; Chambers, D.H. Comparing visual food images versus actual food when measuring emotional response of children. J. Sens. Stud. 2017, 32, e12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, C.A.; Rapoport, L.; Wardle, J. Young children’s food preferences: A comparison of three modalities of food stimuli. Appetite 2000, 35, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildegaard, H.; Olsen, A.; Gabrielsen, G.; Møller, P.; Thybo, A.K. A method to measure the effect of food appearance factors on children’s visual preferences. Food Qual. Pref. 2011, 22, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, M.; Gonera, A.; Varela, P. Children as food designers: The potential of co-creation to make the healthy choice the preferred one. Int. J. Food Des. 2021, 5, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, M.; Myhrer, K.S.; Ares, G.; Varela, P. Listening to children voices in early stages of new product development through co-creation–creative focus group and online platform. Food Res. Int. 2022, 154, 111000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo-Arroyo, E.; Mora, M.; Urkiaga, O.; Pazos, N.; El-Gyar, N.; Gaspar, R.; Pistolese, S.; Beaino, A.; Grosso, G.; Busó, P.; et al. Co-creating snacks: A cross-cultural study with Mediterranean children within the DELICIOUS project. Foods 2025, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitterer Daltoé, M.L.; Schuastz Breda, L.; Belusso, A.C.; Arruda Nogueira, B.; Pegorini Rodrigues, D.; Fiszman, S.; Varela, P. Projective mapping with food stickers: A good tool for better understanding perception of fish in children of different ages. Food Qual. Pref. 2017, 57, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Buso, P.; Mata, A.; Abdelkarim, O.; Aly, M.; Pinilla, J.; Fernandez, A.; Mendez, R.; Alvarez, A.; Valdes, N.; et al. Understanding consumer food choices & promotion of healthy and sustainable Mediterranean diet and lifestyle in children and adolescents through behavioural change actions: The DELICIOUS project. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 75, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BCC Innovation. Simply DELICIOUS. Mediterranean Recipes for Everyday Cooking; Basque Culinary Center: San Sebastián, Spain, 2025; ISBN 978-84-09-69826-4. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, P.; Salvador, A. Structured sorting using pictures as a way to study nutritional and hedonic perception in children. Food Qual. Pref. 2014, 37, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, S.; Valentin, D.; Abdi, H. Free sorting task. In Novel Techniques in Sensory Characterization and Consumer Profiling; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, N.; Robert, P.; Arancibia, C. Understanding older people perceptions about desserts using word association and sorting task methodologies. Food Qual. Pref. 2022, 96, 104423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piochi, M.; Franceschini, C.; Fassio, F.; Torri, L. A large-scale investigation of eating behaviors and meal perceptions in Italian primary school cafeterias: The relationship between emotions, meal perception, and food waste. Food Qual. Pref. 2025, 123, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Ribas, L.; Serra-Majem, L.L.; Aranceta, J. Food preferences of Spanish children and young people: The enKid study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, S45–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinstra, G.G.; Koelen, M.A.; Kok, F.J.; De Graaf, C. The influence of preparation method on children’s liking for vegetables. Food Qual. Pref. 2010, 21, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L.M.; Toma, R.B.; Tuveson, R.V.; Sondhi, L. Color preference and food choice among children. J. Psychol. 1990, 124, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morizet, D.; Depezay, L.; Combris, P.; Picard, D.; Giboreau, A. Effect of labeling on new vegetable dish acceptance in preadolescent children. Appetite 2012, 59, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, J.D.; Carruth, B.R.; Bounds, W.; Ziegler, P.J. Children’s food preferences: A longitudinal analysis. J Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1638–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Jaeger, S.R. Better the devil you know? How product familiarity affects usage versatility of foods and beverages. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016, 55, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proserpio, C.; Almli, V.L.; Sandvik, P.; Sandell, M.; Methven, L.; Wallner, M.; Jilani, H.; Zeinstra, G.G.; Alfaro, B.; Laureati, M. Cross-national differences in child food neophobia: A comparison of five European countries. Food Qual. Pref. 2020, 81, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobos, P.; Januszewicz, A. Food neophobia in children. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2019, 25, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.J.; Mallan, K.M.; Byrne, R.; Margarey, A.; Daniels, L.A. Toddlers food preferences. The impact of novel food exposure, maternal preferences and food neophobia. Appetite 2012, 59, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiz, E.; Balluerka, N. Trait anxiety and self-concept among children and adolescents with food neophobia. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boronat, Ò.; Mora, M.; Romeo-Arroyo, E.; Vázquez-Araújo, L. Unraveling the Mediterranean cuisine. What ingredients drive the flavor of the gastronomies included in the Mediterranean diet? Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 34, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allirot, X.; da Quinta, N.; Chokupermal, K.; Urdaneta, E. Involving children in cooking activities: A potential strategy for directing food choices toward novel foods containing vegetables. Appetite 2016, 103, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, T.; Siegrist, M.; Van der Horst, K. Vegetable variety: An effective strategy to increase vegetable choice in children. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1232–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, L.J.; Wardle, J. Age and gender differences in children’s food preferences. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawajeeh, A.O.; Albar, S.A.; Zhang, H.; Zulyniak, M.A.; Evans, C.E.; Cade, J.E. Impact of taste on food choices in adolescence—Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, B.; Rios, Y.; Arranz, S.; Varela, P. Understanding children’s healthiness and hedonic perception of school meals via structured sorting. Appetite 2020, 144, 104466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, C.; Bouzas, C.; Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; Tur, J.A. Assessing food preferences and neophobias among Spanish adolescents from Castilla–La Mancha. Foods 2023, 12, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nu, C.T.; MacLeod, P.; Barthelemy, J. Effects of age and gender on adolescents’ food habits and preferences. Food Qual. Pref. 1996, 7, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Recipe | Origin | Main Ingredient | Visual Ingredients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monkfish Brodetto | Italy | Fish | Fish, onion, tomato puree, carrot, olives, capers, raisins, parsley |

| Pasta al pesto | Italy | Cereals | Pasta, pesto sauce, burrata, basil |

| Carrot soup | Portugal | Vegetables | Carrot cream, pepper, sprouts |

| Kolkas | Egypt | Vegetables | Taro root, chard, rice |

| Freekeh beraam | Egypt | Cereals | Pasta (freekeh), onion, chicken, spring onion |

| Hake with potatoes and tomato | Spain | Fish | Fish, potatoes, tomatoes, sweet corn |

| Lentils stewed with Portuguese vegetables | Portugal | Legumes | Lentils, cabbage, pumpkin, soy sprouts, carrot, onion, zucchini, chives |

| Sayadieh | Egypt | Fish | Fish, rice, onions, parsley |

| Lebanese mujadara | Lebanon | Legumes | Lentils, rice, onion, yogurt |

| Grilled lamb kabobs | Lebanon | Meat/poultry | Meat, green and yellow bell peppers, onion, parsley |

| Beans salad | Spain | Legumes | Beans, lettuce, tomato, olives, pickled cucumber, onion |

| Beef meatballs with fennel salad | Italy | Meat/poultry | Meatballs, fennel, capers, parmesan cheese |

| Lebanese bean stew | Lebanon | Legumes | Beans, chicken, tomato paste, tomatoes, cilantro |

| Fideuá | Spain | Cereals | Pasta, prawns, cuttlefish, lemon, tomato |

| Kebda eskandarani | Egypt | Meat/poultry | Beef, tomato, green peppers, bread, mint |

| Fattoush salad | Lebanon | Vegetables | Lettuce, cherry tomato, croutons, cucumber, green pepper, radish, green onion, sumac |

| Whole wheat pasta and chicken salad | Italy | Cereals | Pasta, chicken, Cherri tomato, zucchini, olives, basil |

| Beef stew with vegetables | Portugal | Meat/poultry | Beef, carrot, potatoes, green beans, peas, parsley |

| Pisto | Spain | Vegetables | Peppers, zucchini, onion, tomato sauce, chives |

| Fried horse mackerel with tartare sauce | Portugal | Fish | Fish, tartare sauce (mayonnaise, onion, flour, capers, chives, etc.), lemon |

| Country | Acceptance (Mean) |

| Lebanon | 4.1 a |

| Spain | 4.1 a |

| Italy | 3.7 b |

| p-value | <0.0001 |

| Main ingredient | Acceptance (mean) |

| Meat/poultry | 4.5 a |

| Cereals | 4.2 b |

| Fish | 3.9 c |

| Legumes | 3.6 d |

| Vegetables | 3.6 d |

| p-value | <0.0001 |

| Recipe Origin | Acceptance (mean) |

| Lebanese | 4.1 a |

| Egyptian | 4.1 a |

| Italian | 4.0 ab |

| Portuguese | 3.9 ab |

| Spanish | 3.8 c |

| p-value | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urkiaga, O.; Mora, M.; Romeo-Arroyo, E.; Pistolese, S.; Béaino, A.; Grosso, G.; Busó, P.; Pons, J.; Vázquez-Araújo, L. A Sorting Task with Emojis to Understand Children’s Recipe Acceptance. Foods 2025, 14, 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111839

Urkiaga O, Mora M, Romeo-Arroyo E, Pistolese S, Béaino A, Grosso G, Busó P, Pons J, Vázquez-Araújo L. A Sorting Task with Emojis to Understand Children’s Recipe Acceptance. Foods. 2025; 14(11):1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111839

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrkiaga, Olatz, María Mora, Elena Romeo-Arroyo, Sara Pistolese, Angélique Béaino, Giuseppe Grosso, Pablo Busó, Juancho Pons, and Laura Vázquez-Araújo. 2025. "A Sorting Task with Emojis to Understand Children’s Recipe Acceptance" Foods 14, no. 11: 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111839

APA StyleUrkiaga, O., Mora, M., Romeo-Arroyo, E., Pistolese, S., Béaino, A., Grosso, G., Busó, P., Pons, J., & Vázquez-Araújo, L. (2025). A Sorting Task with Emojis to Understand Children’s Recipe Acceptance. Foods, 14(11), 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111839