Omnichannel and Product Quality Attributes in Food E-Retail: A Choice Experiment on Consumer Purchases of Australian Beef in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Omnichannel Retailing and Consumer Choice Behaviours

2.2. Omnichannel Strategies and Product Quality Attributes

3. Methodology

3.1. Discrete Choice Experiment

3.1.1. Identification of Attributes and Corresponding Levels

3.1.2. Determination of Discrete Choice Tasks

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Multinomial Logit Model

3.3.2. Random Parameter Logit Model

3.3.3. Latent Class Model

3.3.4. Willingness to Pay

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Analysis

4.2. Discrete Choice Selection: The Results of MNL Model and RPL Model

4.2.1. Shopping Channel Choice

4.2.2. Brand and Manufacturer Location

4.2.3. Country-of-Origin Traceability

4.3. Different Consumer Clusters: The Results of Latent Class (LC) Model

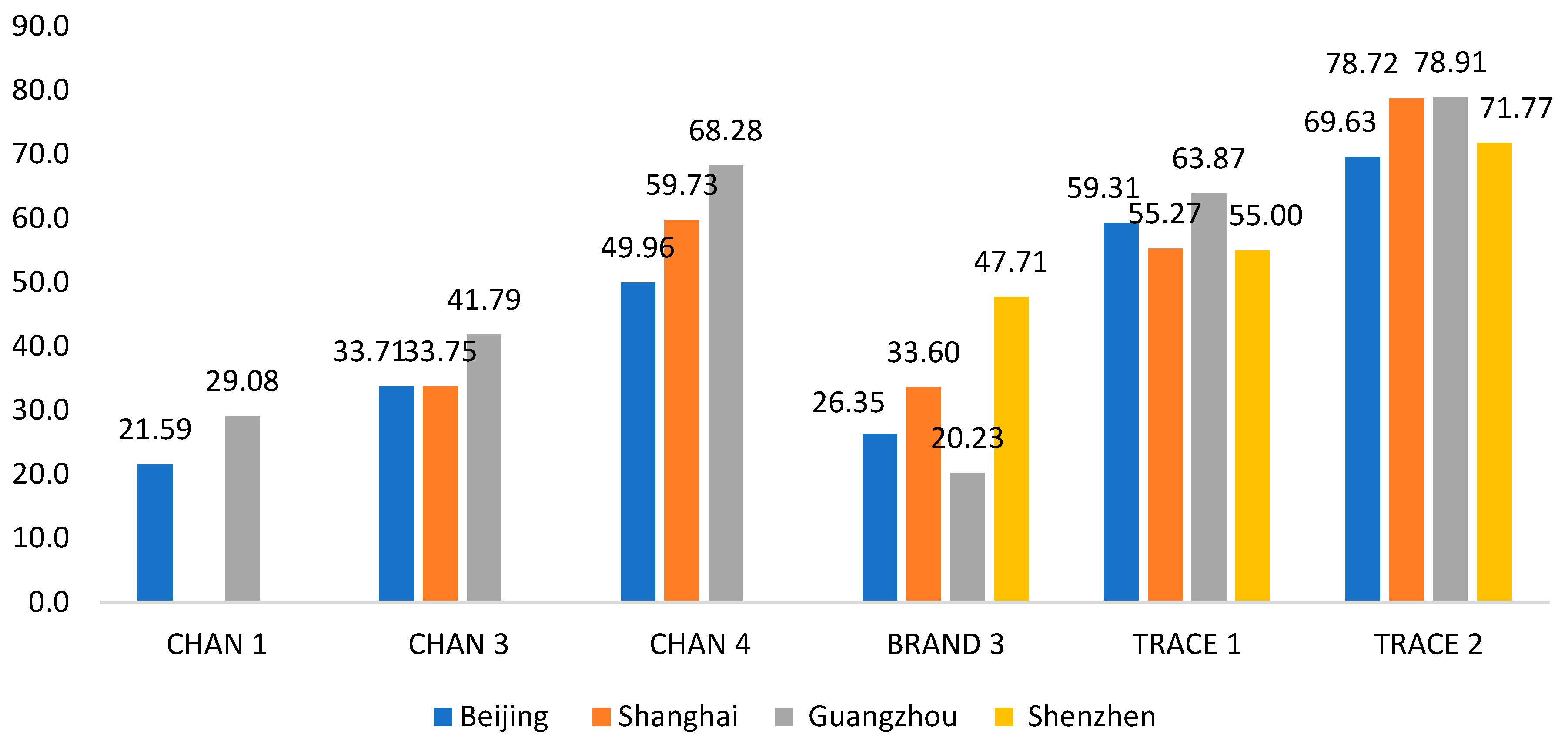

4.4. Willingness to Pay (WTP) for Different Attributes

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Results

5.2. Strategic Contributions to International Food E-Retail

5.3. Practical Implications for International Food E-Retail

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASC | Alternative specific constant |

| DCE | Discrete choice experiment |

| IID | Independent and identically distributed |

| LC | Latent class |

| MLA | Meat & Livestock Australia |

| MNL | Multinomial logit |

| OC | Omnichannel |

| RPL | Random parameter logit |

| WTP | Willingness to pay |

References

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Dong, P.; Liang, R.; Hopkins, D.L.; Holman, B.W.B.; Luo, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Z.; et al. Chinese Consumer Perception and Purchasing Behavior of Beef-Mainly in North and East China. Meat Sci. 2025, 220, 109696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MLA China on Top as Records Reached in 2019. Available online: https://www.mla.com.au/prices-markets/market-news/2019/china-on-top-as-records-reached-in-2019 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- MLA Market Snapshot Beef China. Available online: https://www.integritysystems.com.au/globalassets/mla-corporate/prices--markets/documents/os-markets/export-statistics/oct-2018-snapshots/mla-beef-market-snapshot---global---oct-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- USDA Retail Foods Change and Opportunity. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Retail%20Foods_Beijing%20ATO_China%20-%20Peoples%20Republic%20of_8-17-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Chopra, S. The Evolution of Omni-Channel Retailing and Its Impact on Supply Chains. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 30, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotarelo, M.; Calderón, H.; Fayos, T. A Further Approach in Omnichannel LSQ, Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2021, 49, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, O.; Somogyi, S.; Charlebois, S. Food Choice in the E-Commerce Era: A Comparison between Business-to-Consumer (B2C), Online-to-Offline (O2O) and New Retail. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1215–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xie, X.; Ma, H. Evolution of Omni-Channel Business Models: A New Community-Based Omni-Channel and Data-Enabled Ecosystem. J. Contemp. Mark. Sci. 2021, 4, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Mohiuddin Babu, M.; Hossain, T.M.T.; Dey, B.L.; Liu, H.; Singh, P. Omnichannel Management Capabilities in International Marketing: The Effects of Word of Mouth on Customer Engagement and Customer Equity. Int. Mark. Rev. 2024, 41, 42–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrai, L.A.; Lascu, D.-N.; Manrai, A.K. Interactive Effects of Country of Origin and Product Category on Product Evaluations. Int. Bus. Rev. 1998, 7, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, N.; Parker, P. Marketing Universals: Consumers’ Use of Brand Name, Price, Physical Appearance, and Retailer Reputation as Signals of Product Quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Espejel, J.; Fandos, C.; Flavián, C. The Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Quality Attributes on Consumer Behaviour for Traditional Food Products. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2007, 17, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Chang, S.R. When and How Brands Affect Importance of Product Attributes in Consumer Decision Process. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, R.; Quester, P. Do Consumer Expectations Match Experience? Predicting the Influence of Price and Country of Origin on Perceptions of Product Quality. Int. Bus. Rev. 2009, 18, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.G.; Holdsworth, D.K.; Mather, D.W. Country-of-Origin and Choice of Food Imports: An in-Depth Study of European Distribution Channel Gatekeepers. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, G.R.; Cameron, R.C. Consumer Perception of Product Quality and the Country-of-Origin effect. J. Int. Mark. 1994, 2, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainam, P.; Bahadir, S.C. Emerging Market Firms’ Internationalization Pricing Strategies: The Role of Country of Origin and Organizational Learning. J. Int. Mark. 2024, 32, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S.; De Nisco, A.; Petruzzellis, L. Country-of-Origin Image and Consumer Brand Evaluation: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 33, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storøy, J.; Thakur, M.; Olsen, P. The TraceFood Framework—Principles and Guidelines for Implementing Traceability in Food Value Chains. J. Food Eng. 2013, 115, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelseth, P.; Wongthatsanekorn, W.; Charoensiriwath, C. Food Product Traceability and Customer Value. Global Bus. Rev. 2014, 15, 87S–105S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jackson, J.E. Examining Customer Channel Selection Intention in the Omni-Channel Retail Environment. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 208, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A. Are Online and Offline Prices Similar? Evidence from Large Multi-Channel Retailers. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melacini, M.; Perotti, S.; Rasini, M.; Tappia, E. E-Fulfilment and Distribution in Omni-Channel Retailing: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Lau, K.H.; Teo, L.K.Y. Drivers and Barriers of Omni-Channel Retailing in China: A Case Study of the Fashion and Apparel Industry. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 657–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, A.; Sabbadin, E. The New Paradigm of the Omnichannel Retailing: Key Drivers, New Challenges and Potential Outcomes Resulting from the Adoption of an Omnichannel Approach. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 13, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopadjieva, E.; Dholakia, U.M.; Benjamin, B. A Study of 46,000 Shoppers Shows That Omnichannel Retailing Works. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zipser, D.; Seong, J.; Woetzel, L. Five Consumer Trends Shaping the next Decade of Growth in China. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/cn/our-insights/our-insights/five-consumer-trends-shaping-the-next-decade-of-growth-in-china (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Peavy, K. China Retail’s Newest Inflection Point: From E-Commerce to Omni-Channel. Available online: https://www.chinacenter.net/2018/china-currents/17-1/china-retails-newest-inflection-point-e-commerce-omni-channel (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Botica, L. China’s Omni-Channel Marketing Boom—Why Is Omni-Channel Marketing So Important? Available online: https://www.isentia.com/latest-reads/chinas-omni-channel-marketing-boom/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Wolf, L.; Steul-Fischer, M. Factors of Customers’ Channel Choice in an Omnichannel Environment: A Systematic Literature Review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 73, 1579–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, R. Omnichannel Shoppers Pay Off for Grocery Chains. Available online: https://www.supermarketnews.com/consumer-trends/omnichannel-shoppers-pay-off-for-grocery-chains (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Ryu, J.S. Consumer Characteristics and Shopping for Fashion in the Omni-Channel Retail Environment. Asian J. Bus. Environ. 2019, 9, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company What Is Omnichannel Marketing? Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-omnichannel-marketing (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Park, S.; Lee, D. An Empirical Study on Consumer Online Shopping Channel Choice Behavior in Omni-Channel Environment. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgoni, G.M. “Omni-Channel” Retail Insights and the Consumer’s Path-to-Purchase: How Digital Has Transformed the Way People Make Purchasing Decisions. J. Advert. Res. 2014, 54, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Powell, W.; Foth, M.; Natanelov, V.; Miller, T.; Dulleck, U. Strengthening Consumer Trust in Beef Supply Chain Traceability with a Blockchain-Based Human-Machine Reconcile Mechanism. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180, 105886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, H.; Kuznesof, S.; Dean, M.; Chan, M.-Y.; Clark, B.; Home, R.; Stolz, H.; Zhong, Q.; Liu, C.; Brereton, P.; et al. Chinese Consumer’s Attitudes, Perceptions and Behavioural Responses towards Food Fraud. Food Control 2019, 95, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Foth, M.; Powell, W.; McQueenie, J. What Are the Effects of Short Video Storytelling in Delivering Blockchain-Credentialed Australian Beef Products to China? Foods 2021, 10, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.J. A New Approach to Consumer Theory. J. Polit. Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. The Measurement of Urban Travel Demand. J. Public Econ. 1974, 3, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yu, X.; Li, C.; McFadden, B.R. The Interaction between Country of Origin and Genetically Modified Orange Juice in Urban China. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Umberger, W.J. A Choice Experiment Model for Beef: What US Consumer Responses Tell Us about Relative Preferences for Food Safety, Country-of-Origin Labeling and Traceability. Food Policy 2007, 32, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Snell, H.A.; Ma, H. Consumers’ Valuation for Food Traceability in China: Does Trust Matter? Food Policy 2019, 88, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, W.; Louviere, J.; Swait, J. Introduction to Attribute-Based Stated Choice Methods; NOAA-National Oceanic Athmospheric Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Li, H.; Li, Y. Preferences of Chinese Consumers for the Attributes of Fresh Produce Portfolios in an E-Commerce Environment. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummett, R.G.; Nayga, R.M.; Wu, X. On the Use of Cheap Talk in New Product Valuation. Econ. Bull. 2007, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ubilava, D.; Foster, K. Quality Certification vs. Product Traceability: Consumer Preferences for Informational Attributes of Pork in Georgia. Food Policy 2009, 34, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Greene, W.H. The Mixed Logit Model: The State of Practice. Transportation 2003, 30, 133–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D.; Train, K. Mixed MNL Models for Discrete Response. J. Appl. Econ. 2000, 15, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, D.; Rose, J.; Greene, W. Applied Choice Analysis: A Primer; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall, P.C.; Adamowicz, W.L. Understanding Heterogeneous Preferences in Random Utility Models: A Latent Class Approach. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2002, 23, 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Hopkins, D.L.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X. Consumption Patterns and Consumer Attitudes to Beef and Sheep Meat in China. Am. J. Food Nutr. 2016, 4, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Wang, R.; Hu, Y. Consumers’ Purchase Intentions toward Traceable beef—Evidence from Beijing, China. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2017, 7, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cao, S.; Dulleck, U.; Powell, W.; Turner-Morris, C.; Natanelov, V.; Foth, M. BeefLedger Blockchain-Credentialed Beef Exports to China: Early Consumer Insights; Queensland University of Technology: Brisbane, Australia, 2020; ISBN 9781925553215. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Grebitus, C.; DeLong, K. Consumer Preferences for Beef Quality Grades on Imported and Domestic Beef. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2023, 50, 1064–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Wang, H.H.; Wu, L.; Olynk, N.J. Modeling Heterogeneity in Consumer Preferences for Select Food Safety Attributes in China. Food Policy 2011, 36, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Wang, H.H.; Olynk, N.J.; Wu, L.; Bai, J. Chinese Consumers’ Demand for Food Safety Attributes: A Push for Government and Industry Regulations. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2012, 94, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciuto, L.; Tarasuk, V.; Yatchew, A. Socio-Demographic Influences on Food Purchasing among Canadian Households. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, A.; Boncinelli, F.; Gerini, F.; Marone, E. Determinants of Online Food Purchasing: The Impact of Socio-Demographic and Situational Factors. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juaneda-Ayensa, E.; Mosquera, A.; Sierra Murillo, Y. Omnichannel Customer Behavior: Key Drivers of Technology Acceptance and Use and Their Effects on Purchase Intention. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Number of Levels | Specific Attribute Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shopping Channel [32] | 4 |

| |||||

| Brand and Manufacturer Location [39] | 3 |

| |||||

| Country-of-Origin Traceability [19] | 3 |  QR code-enabled traceability |  MLA origin label | None | |||

| Price [10] | 4 | CNY 35 | CNY 50 | CNY 65 | CNY 80 | ||

| Attribute | Brisket Choice 1 | Brisket Choice 2 | Brisket Choice 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shopping Channel | Purchase from e-commerce marketplace | Purchase from new omnichannel (OC) offline stores | None |

| Brand and Manufacturer Location | Australian brand, manufactured in China | Australian brand, manufactured in China | |

| Country-of-Origin Traceability |  QR code-enabled traceability |  MLA origin label | |

| Price (per 500 g) | CNY 50 | CNY 80 | |

| I would buy: | o | O | o |

| Profile | Beijing | Shanghai | Guangzhou | Shenzhen | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 232 | 221 | 219 | 200 | 872 |

| Gender distribution—Female (%) | 59.1 | 53.8 | 68 | 56.5 | 59.4 |

| Age group breakdown (%) | |||||

| 18–25 | 14.2 | 17.6 | 29.2 | 12.5 | 18.5 |

| 26–30 | 21.6 | 19.5 | 28.3 | 29 | 24.4 |

| 31–40 | 37.5 | 20.4 | 31.1 | 44 | 33 |

| 41–50 | 17.7 | 16.7 | 9.1 | 13 | 14.2 |

| 51–60 | 6.9 | 15.8 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 6.7 |

| Above 60 | 2.2 | 10 | 0.5 | 0 | 3.2 |

| Education level (%) | |||||

| Middle school and below | 0.4 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.8 |

| High school | 13.4 | 26.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 12 |

| Bachelor | 60.3 | 53.4 | 68 | 73 | 63.4 |

| Master | 24.6 | 16.7 | 25.1 | 22 | 22.1 |

| PhD and above | 1.3 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Taxable monthly income range (%) | |||||

| Below 3000 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 2 | 4.5 |

| 3000–5999 | 15.9 | 26.7 | 16 | 10.5 | 17.4 |

| 6000–9999 | 31.5 | 36.2 | 30.1 | 36.5 | 33.5 |

| 10,000–14,999 | 18.1 | 14 | 24.2 | 24 | 20 |

| 15,000–19,999 | 15.5 | 6.8 | 9.6 | 15.5 | 11.8 |

| 20,000–29,999 | 9.1 | 5.4 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 7.5 |

| 30,000–49,999 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 4 | 4.4 |

| Above 50,000 | 0 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1 | 1 |

| Marital status—Married (%) | 67.7 | 61.5 | 51.6 | 69.5 | 62.5 |

| Family size breakdown (%) | |||||

| 1–2 | 22 | 32.6 | 18.7 | 19 | 23.2 |

| 3–4 | 63.8 | 59.7 | 62.1 | 74 | 64.7 |

| 5 and above | 14.2 | 7.7 | 19.2 | 7 | 12.2 |

| Number of children (%) | |||||

| None | 47.4 | 62.4 | 53.9 | 46 | 52.5 |

| 1 | 41.8 | 31.2 | 32.4 | 47 | 38 |

| 2 | 10.3 | 6.3 | 12.3 | 7 | 9.1 |

| 3 and above | 0.4 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Variable | Beijing (BJ) | Shanghai (SH) | Guangzhou (GZ) | Shenzhen (SZ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHAN 1 | 0.42561 *** (0.12966) | 0.05481 (0.10144) | 0.72553 *** (0.14073) | 0.03572 (0.11458) |

| CHAN 3 | 0.65565 *** (0.13288) | 0.30980 *** (0.10896) | 1.04417 *** (0.13515) | 0.13188 (0.13760) |

| CHAN 4 | 0.97407 *** (0.14490) | 0.54265 *** (0.11455) | 1.70540 *** (0.16655) | 0.10757 (0.12692) |

| BRAND 1 (BJ) | 0.02374 (0.12010) | - | - | - |

| BRAND 2 (SH, GZ, SZ) | - | 0.12393 (0.08920) | 0.10527 (0.11524) | 0.34181 *** (0.10887) |

| BRAND 3 | 0.50948 *** (0.12075) | 0.30901 *** (0.09099) | 0.50936 *** (0.13054) | 0.77913 *** (0.11691) |

| TRACE 1 | 1.14493 *** (0.12492) | 0.50310 *** (0.08218) | 1.58314 *** (0.14004) | 0.89612 *** (0.10508) |

| TRACE 2 | 1.36139 *** (0.12880) | 0.71590 *** (0.09025) | 1.97351 *** (0.15298) | 1.17085 *** (0.11343) |

| Non-random parameters in utility functions | ||||

| PRICE | −0.01949 *** (0.00284) | −0.00906 *** (0.00232) | −0.02500 *** (0.00314) | −0.01639 *** (0.00275) |

| NONE | −1.12899 *** (0.19990) | −2.19088 *** (0.19309) | −0.70530 *** (0.20480) | −1.18719 *** (0.19745) |

| Standard deviation of the random parameters | ||||

| CHAN 1 | 0.61783 *** (0.21754) | 0.36360 (0.23404) | 0.55911 ** (0.26618) | 0.00450 (0.40929) |

| CHAN 3 | 0.72870 *** (0.19952) | 0.63058 *** (0.18173) | 0.17674 (0.52786) | 0.99348 *** (0.17812) |

| CHAN 4 | 0.80956 *** (0.19132) | 0.32119 (0.28030) | 0.75154 *** (0.20355) | 0.14476 (0.43376) |

| BRAND 2 | 0.98281 *** (0.15813) | 0.56915 *** (0.13508) | 0.63862 *** (0.18066) | 0.70299 *** (0.14227) |

| BRAND 3 | 0.97395 *** (0.15201) | 0.60096 *** (0.14570) | 1.06528 *** (0.15400) | 0.86175 *** (0.13603) |

| TRACE 1 | 0.96872 *** (0.15753) | 0.24525 (0.22843) | 0.93989 *** (0.15275) | 0.51082 *** (0.15450) |

| TRACE 2 | 0.96537 *** (0.15056) | 0.31019 (0.19561) | 0.94789 *** (0.15327) | 0.60704 *** (0.15184) |

| Summary statistics | ||||

| Observations | 1856 | 1768 | 1752 | 1600 |

| McFadden pseudo R2 | 0.2413985 | 0.2814263 | 0.3075762 | 0.2138844 |

| Log likelihood | −1546.80691 | −1395.71917 | −1332.75575 | −1381.81805 |

| Inf. Cr. AIC | 3125.6 | 2823.4 | 2697.5 | 2795.6 |

| Variable | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHAN 1 | −0.00764 (0.13108) | 0.86888 *** (0.15662) | 0.11760 (0.14355) | 0.27033 * (0.16086) |

| CHAN 3 | 0.10346 (0.12638) | 1.06062 *** (0.15985) | 0.48819 *** (0.12763) | 0.62451 *** (0.17241) |

| CHAN 4 | 0.35581 ** (0.14601) | 1.59039 *** (0.16367) | 0.97312 *** (0.16827) | 0.45103 ** (0.20346) |

| BRAND 2 | 0.04658 (0.09802) | 0.00532 (0.11452) | 0.16086 (0.12239) | 0.47132 *** (0.12861) |

| BRAND 3 | 0.33936 *** (0.12013) | 0.33494 *** (0.12360) | 0.33060 ** (0.12905) | 1.12470 *** (0.16140) |

| TRACE 1 | 0.15007 (0.12234) | 1.27166 *** (0.14816) | 0.16844 (0.12599) | 2.39117 *** (0.21848) |

| TRACE 2 | 0.35975 *** (0.12082) | 1.35688 *** (0.15269) | 0.37536 *** (0.13626) | 2.82650 *** (0.23407) |

| PRICE | 0.03138 *** (0.00431) | −0.02593 *** (0.00344) | −0.06338 *** (0.00569) | −0.01628 *** (0.00513) |

| NONE | −1.26030 *** (0.42901) | 0.65184 ** (0.26305) | −7.01139 *** (0.61615) | −0.68787 * (0.39605) |

| Summary Statistics | ||||

| Class Prob. | 0.22866 *** | 0.20719 *** | 0.26076 *** | 0.30339 *** |

| McFadden Pseudo R2 | 0.3099125 | |||

| Log Likelihood | −5288.77461 | |||

| Inf. Cr. AIC | 10,655.5 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, Y.; Cao, S.; Bryceson, K.; Currey, P.; Yaseen, A. Omnichannel and Product Quality Attributes in Food E-Retail: A Choice Experiment on Consumer Purchases of Australian Beef in China. Foods 2025, 14, 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101813

Hou Y, Cao S, Bryceson K, Currey P, Yaseen A. Omnichannel and Product Quality Attributes in Food E-Retail: A Choice Experiment on Consumer Purchases of Australian Beef in China. Foods. 2025; 14(10):1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101813

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Yaochen, Shoufeng Cao, Kim Bryceson, Phillip Currey, and Asif Yaseen. 2025. "Omnichannel and Product Quality Attributes in Food E-Retail: A Choice Experiment on Consumer Purchases of Australian Beef in China" Foods 14, no. 10: 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101813

APA StyleHou, Y., Cao, S., Bryceson, K., Currey, P., & Yaseen, A. (2025). Omnichannel and Product Quality Attributes in Food E-Retail: A Choice Experiment on Consumer Purchases of Australian Beef in China. Foods, 14(10), 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101813