Exploring the Impact of Human–Animal Connections and Trust in Labeling Consumers’ Intentions to Buy Cage-Free Eggs: Findings from Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Reviewing the Literature and Developing Hypotheses

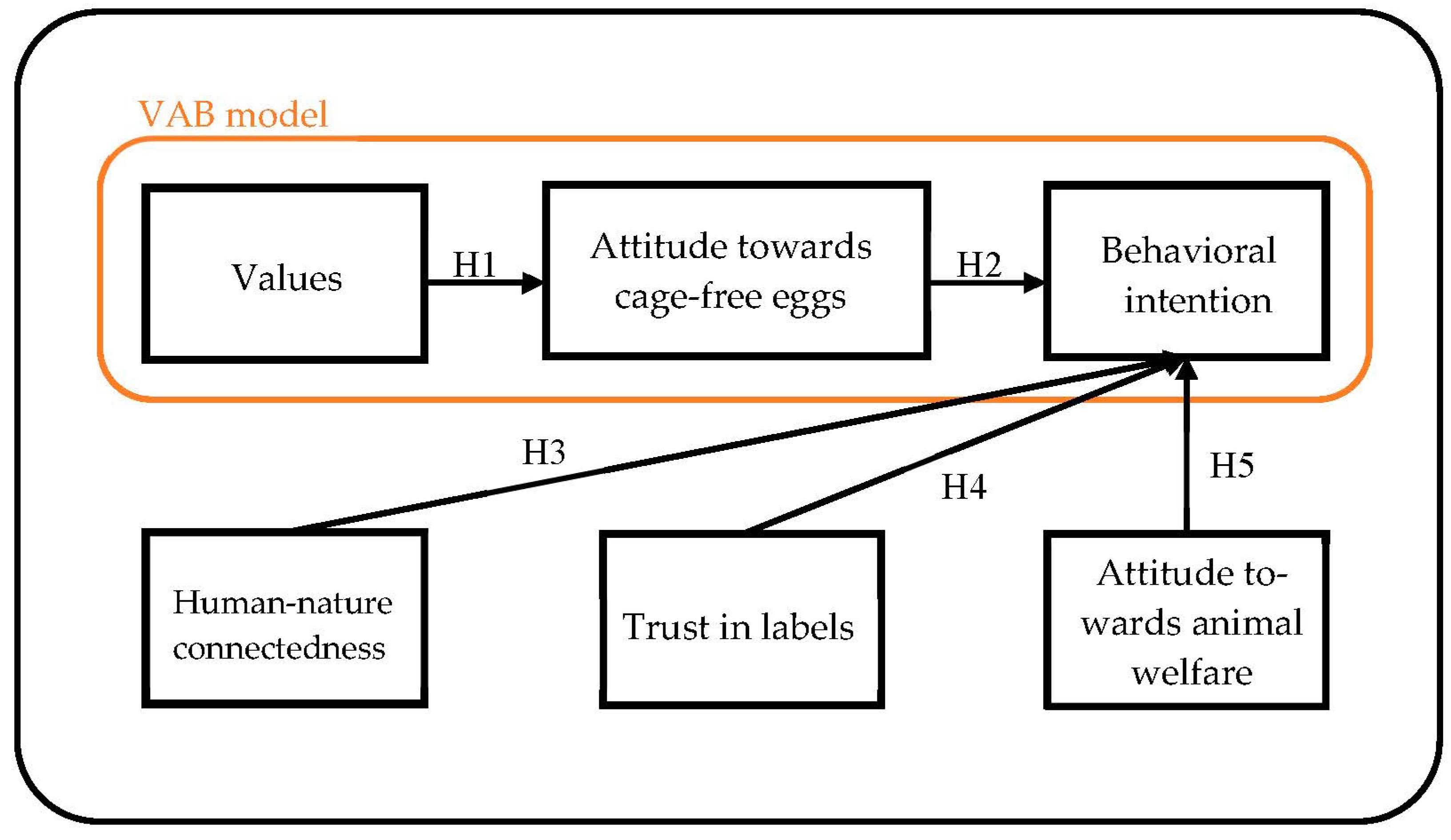

2.1. VAB Model

2.1.1. Attitude towards Cage-Free Eggs Driven by Values

2.1.2. Relation between Attitude towards Cage-Free Eggs and Behavioral Intentions

2.2. Human–Nature Connectedness

2.3. Trust in Labels

2.4. Attitude towards Animal Welfare

3. Supplies and Procedures

3.1. Framework of Research

3.2. Survey Design

3.3. Data Sampling and Collection

3.4. Methods for Analyzing Data

4. Evaluation and Findings

4.1. Assessing Models: Gauging Reliability and Validity

4.2. Model Fitness Test

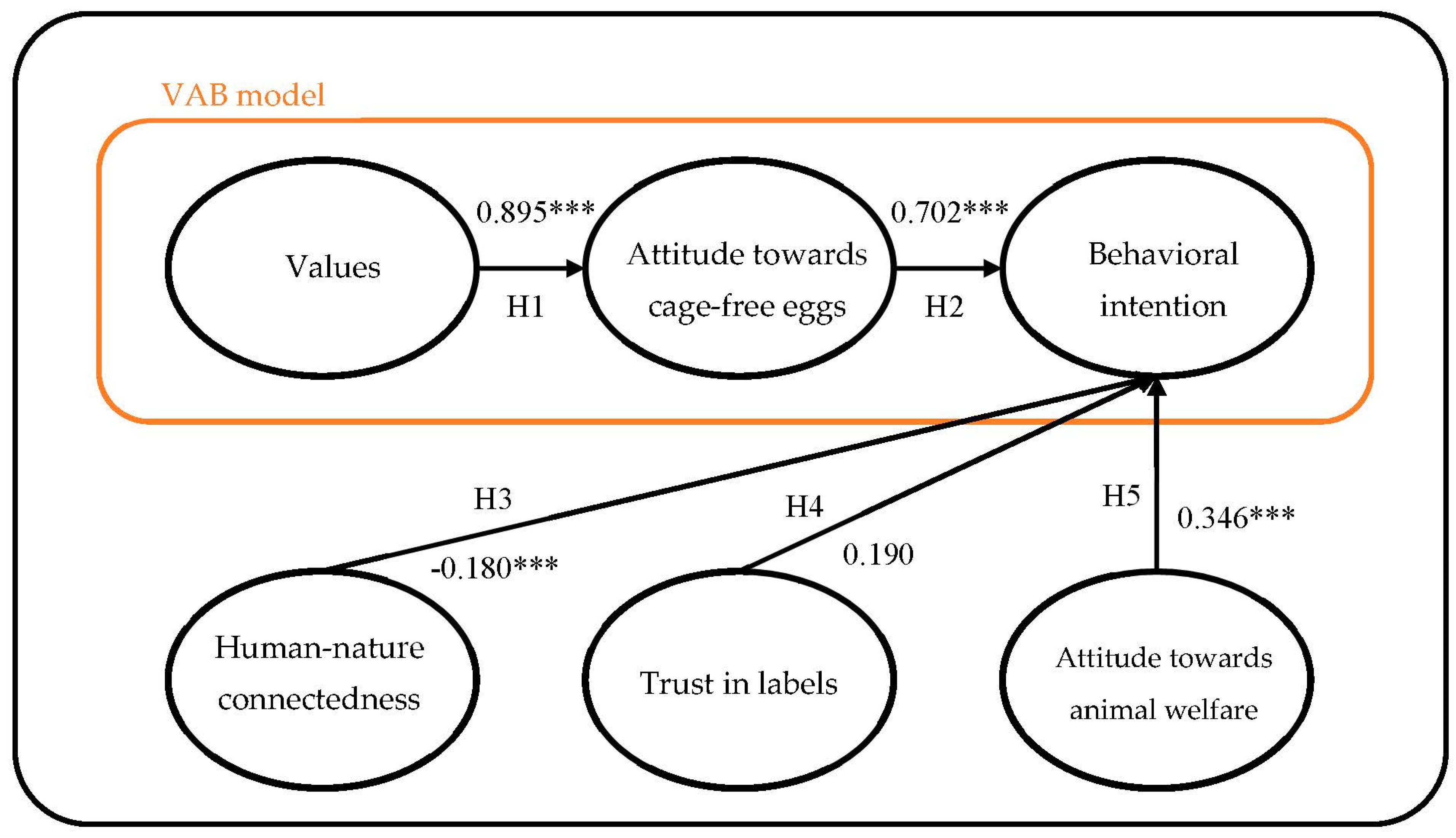

4.3. Model Path Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Concluding Remarks, Constraints, and Prospects for Future Study

6.1. Research Conclusions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Study Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saunois, M.; Jackson, R.B.; Bousquet, P.; Poulter, B.; Canadell, J.G. The growing role of methane in anthropogenic climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 120207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseten, T.; Sanjorjo, R.A.; Kwon, M.; Kim, S.W. Strategies to Mitigate Enteric Methane Emissions from Ruminant Animals. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Environment Assembly. 5/4. Animal Welfare–Environment–Sustainable Development Nexus. 2022. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/39731/K2200707%20-%20UNEP-EA.5-Res.1%20-%20ADVANCE.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Alonso, M.E.; González-Montaña, J.R.; Lomillos, J.M. Consumers’ Concerns and Perceptions of Farm Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D.J. Moving beyond the “Five Freedoms” by Updating the “Five Provisions” and Introducing Aligned “Animal Welfare Aims”. Animals 2016, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallgren, T.; Lundeheim, N.; Wallenbeck, A.; Westin, R.; Gunnarsson, S. Rearing Pigs with Intact Tails—Experiences and Practical Solutions in Sweden. Animals 2019, 9, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Code of Conduct for Responsible Food Business and Marketing Practices. 2021. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/f2f_sfpd_coc_final_en.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- European Commission. European Citizens’ Initiative: Commission to Propose Phasing Out of Cages for Farm Animals. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_3297 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022L2464 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Thorslund, C.A.; Aaslyng, M.D.; Lassen, J. Perceived importance and responsibility for market-driven pig welfare: Literature review. Meat Sci. 2017, 125, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture (MOA). Exploration of Supply and Demand and Production and Marketing of Eggs in Our Country. 2023. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.tw/redirect_files.php?id=48785&file_name=NCIjlo6ommJfoHCt38xWGSlashgXUTfFjzxlVodK18X5WGPlus10Vg2WGPlusg96s89ZGHgY2FiCq2YR (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Yang, Q. Chinese egg producers’ attitudes and intentions towards improving animal welfare. In Proceedings of the 1st International Electronic Conference on Animals—Global Sustainability and Animals: Science, Ethics and Policy, Basel, Switzerland, 20 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.J.; Cranfield, J.; Chen, C.; Widowski, T. Heterogeneous informational and attitudinal impacts on consumer preferences for eggs from welfare enhanced cage systems. Food Policy 2020, 99, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chryssohoidis, G.M.; Krystallis, A. Organic Consumers’ Personal Values Research: Testing and Validating the List of Values (LOV) Scale and Implementing a Value-based Segmentation Task. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, P.; Verplanken, B.; Olsen, S.O. Ethical values and motives driving organic food choice. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2006, 5, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xue, Y.; Geng, L.; Xu, Y.; Meline, N.N. The Influence of Environmental Values on Consumer Intentions to Participate in Agritourism—A Model to Extend TPB. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2022, 35, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. The ecology of human–nature interactions. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 287, 20191882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, G.; Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Rai, D.P. Developing a sustainable smart city framework for developing economies: An Indian context. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Song, H. Investigating Young Consumers’ Purchasing Intention of Green Housing in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Eurobarometer. Attitudes of Europeans towards Animal Welfare. Animal Welfare. 2016. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2096 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Zanoli, R.; Naspetti, S.; Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Mediation and moderation in food-choice models: A study on the effects of consumer trust in logo on choice. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2015, 72–73, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretner, G.; Darnall, N.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Are consumers willing to pay for circular products? The role of recycled and second- hand attributes, messaging, and third-party certification. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanville, C.; Abraham, C.; Coleman, G. Human Behaviour Change Interventions in Animal Care and Interactive Settings: A Review and Framework for Design and Evaluation. Animals 2020, 10, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Schilstra, L.; Fischer, A.R.H. Consumer Moral Dilemma in the Choice of Animal-Friendly Meat Products. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaauw, P.A.M.; Vinke, C.M.; van Hagen, M.A.E.; Lipman, L.J.A. A One Health Perspective on the Human–Companion Animal Relationship with Emphasis on Zoonotic Aspects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuseini, A.; Sulemana, I. An exploratory study of the influence of attitudes towards animal welfare on meat consumption in Ghana. Food Ethics 2018, 2, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.J.C.; Izmirli, S.; Aldavood, S.J.; Alonso, M.; Choe, B.L.; Hanlon, A.; Handziska, A.; Illmann, G.; Keeling, L.; Kennedy, M.; et al. Students’ attitudes to animal welfare and rights in Europe and Asia. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S.; Huang, D.-M. The Influence of Green Restaurant Decision Formation Using the VAB Model: The Effect of Environmental Concerns upon Intent to Visit. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8736–8755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-C.; Chang, H.-P. The Effect of Novel and Environmentally Friendly Foods on Consumer Attitude and Behavior: A Value-Attitude-Behavioral Model. Foods 2022, 11, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D.; Li, J. The intention to adopt electric vehicles: Driven by functional and non-functional values. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellano, A.; Valor, C.; Chuvieco, E. The Influence of Religion on Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; Yan, L.; Guo, R.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, B.N. The Defining Role of Environmental Self-Identity among Consumption Values and Behavioral Intention to Consume Organic Food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Martens, P.; Khalid, A. Impact of Ethical Ideologies on Students’ Attitude toward Animals—A Pakistani Perspective. Animals 2023, 13, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, P.D.; Araújo, W.M.C.; Patarata, L.; Fraqueza, M.J. Understanding the Main Factors That Influence Consumer Quality Perception and Attitude towards Meat and Processed Meat Products. Meat Sci. 2022, 193, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako, G.K.; Dzogbenuku, R.K.; Abubakari, A. Do green knowledge and attitude influence the youth’s green purchasing? Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2020, 69, 1609–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, L.P.; Wang, M.H.; Jiang, X.Q. Propensity of green consumption behaviors in representative cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynalova, Z.; Namazova, N. Revealing Consumer Behavior toward Green Consumption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, P.M.; Pappaioanou, M.; Bardosh, K.L.; Conti, L. A planetary vision for one health. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e001137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Geng, L.; Schultz, P.W.; Zhou, K. Mindfulness Increases the Belief in Climate Change: The Mediating Role of Connectedness with Nature. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan-Jason, G.; de Mazancourt, C.; Parmesan, C.; Singer, M.C.; Loreau, M. Human–nature connectedness as a pathway to sustainability: A global meta-analysis. Conserv. Lett. 2022, 15, e12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S.; Xu, F.; Zhang, H. Influence of tourists’ environmental tropisms on their attitudes to tourism and nature conservation in natural tourist destinations: A case study of Jiuzhaigou National Park in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, D.C.; Vermeir, I.; Petrescu-Mag, R.M. Consumer Understanding of Food Quality, Healthiness, and Environmental Impact: A Cross-National Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Cicia, G.; Del Giudice, T.; Menna, C.; Nardone, G.; Seccia, A. Parents’ trust in food safety and healthiness of children’s diets: A TPB model explaining the role of retailers and government. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2021, 23, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.M.; Liu, R.; Moritaka, M.; Fukuda, S. Determinants of consumer intention to purchase food with safety certifications in emerging markets: Evidence from Vietnam. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 13, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, J.; Prandota, A.; Rejman, K.; Halicka, E.; Tul-Krzyszczuk, A. Certification Labels in Shaping Perception of Food Quality—Insights from Polish and Belgian Urban Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Negurită, O.; Grecu, I.; Grecu, G.; Mitran, P.C. Consumers’ Decision-Making Process on Social Commerce Platforms: Online Trust, Perceived Risk, and Purchase Intentions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Rodrigues, C.-A. A comparison of organic-certified versus non-certified natural foods: Perceptions and motives and their influence on purchase behaviors. Appetite 2022, 168, 105698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moruzzo, R.; Riccioli, F.; Boncinelli, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Tang, Y.; Tinacci, L.; Massai, T.; Guidi, A. Urban Consumer Trust and Food Certifications in China. Foods 2020, 9, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; Aiking, H. Considering how farm animal welfare concerns may contribute to more sustainable diets. Appetite 2022, 168, 105786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Janssen, M. How and Why Does the Attitude-Behavior Gap Differ between Product Categories of Sustainable Food? Analysis of Organic Food Purchases Based on Household Panel Data. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnovale, F.; Jin, X.; Arney, D.; Descovich, K.; Guo, W.; Shi, B.; Phillips, C.J.C. Chinese Public Attitudes towards, and Knowledge of, Animal Welfare. Animals 2021, 11, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, J.N.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.J.; Tilbrook, A.J. Costs and Benefits of Improving Farm Animal Welfare. Agriculture 2021, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.; Colmekcioglu, N. Understanding guests’ behavior to visit green hotels: The role of ethical ideology and religiosity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Oh, K.W. Influencing Factors of Chinese Consumers’ Purchase Intention to Sustainable Apparel Products: Exploring Consumer “Attitude–Behavioral Intention” Gap. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My, N.H.; Demont, M.; Verbeke, W. Inclusiveness of consumer access to food safety: Evidence from certified rice in Vietnam. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tao, J.; Chu, M. Behind the label: Chinese consumers’ trust in food certification and the effect of perceived quality on purchase intention. Food Control 2020, 108, 106825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Dao, T.K.; Duong, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, V.K.; Dao, T.L. Role of consumer ethnocentrism on purchase intention toward foreign products: Evidence from data of Vietnamese consumers with Chinese products. Heliyon 2023, e13069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsved, S.M.; Basnov, M.; Holm-Christensen, K.; Hjollund, N.H. Response Rate and Completeness of Questionnaires: A Randomized Study of Internet versus Paper-and-Pencil Versions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2007, 9, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Viaene, J. Beliefs, attitude and behaviour towards fresh meat consumption in Belgium: Empirical evidence from a consumer survey. Food Qual. Prefer. 1999, 10, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The assessment of reliability. Psychom. Theory 1994, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spartano, S.; Grasso, S. Consumers’ Perspectives on Eggs from Insect-Fed Hens: A UK Focus Group Study. Foods 2021, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Zhao, Q.; Santibanez-Gonzalez, E.D. How Chinese Consumers’ Intentions for Purchasing Eco-Labeled Products Are Influenced by Psychological Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Yao, L.; Yao, L.; Liu, J. Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for eco-labelled eggs: A discrete choice experiment from Chongqing in China. Br. Food J. 2022, 125, 1683–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, N.; Ugaz, C.; Cañon-Jones, H. Perception of Animal Welfare in Laying Hens and Willingness-to-Pay of Eggs of Consumers in Santiago, Chile. Proceedings 2021, 73, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sass, C.A.; Pimentel, T.C.; Guimarães, J.T.; Silva, R.; Pagani, M.M.; Silva, M.C.; Queiroz, M.F.; Cruz, A.G.; Esmerino, E.A. How buyer-focused projective techniques can help to gain insights into consumer perceptions about different types of eggs. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploll, U.; Stern, T. From diet to behaviour: Exploring environmental- and animal-conscious behaviour among Austrian vegetarians and vegans. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3249–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Bleidorn, W.; Schwaba, T.; Chen, S. Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarial, G.S.K.; Bozkurt, Z. Animal welfare attitudes of pet owners: An investigation in central and western parts of turkey. Kocatepe Vet. J. 2020, 13, 388–395. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, I.; Waris, I.; Amin ul Haq, M. Predicting eco-conscious consumer behavior using theory of planned behavior in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 15535–15547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 341 | Item | Population | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 164 | 48.1% |

| Female | 177 | 51.9% | |

| Age | 20 years and below | 29 | 8.5% |

| 21–30 years | 127 | 37.2% | |

| 31–40 years | 43 | 12.6% | |

| 41–50 years | 68 | 19.9% | |

| 51–60 years | 48 | 14.1% | |

| 60 years and above | 26 | 7.6% | |

| Level of Education | Middle school or below | 17 | 5.0% |

| High school/vocational | 78 | 22.9% | |

| College/university | 206 | 60.4% | |

| Master’s or above | 40 | 11.7% | |

| Monthly personal income | Less than NTD 20,000 (USD 660) (inclusive) | 75 | 22.0% |

| NTD 20,001–40,000 (USD 660–1320) | 127 | 37.2% | |

| NTD 40,001–60,000 (USD 1320–1980) | 83 | 24.3% | |

| NTD 60,001–80,000 (USD 1980–2640) | 32 | 9.4% | |

| Above NTD 80,001 (USD 2640) | 24 | 7.0% | |

| Occupation | Student | 61 | 17.9% |

| Army, civil service, and education | 36 | 10.6% | |

| Service industry | 66 | 19.4% | |

| Freelance | 29 | 8.5% | |

| Traditional manufacturing | 39 | 11.4% | |

| Specialized occupation (e.g., doctor and lawyer) | 18 | 5.3% | |

| Other | 92 | 27.0% | |

| Pet ownership | Yes | 125 | 36.7% |

| No | 216 | 63.3% | |

| Dietary habits | Omnivorous | 318 | 93.3% |

| Vegan | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Ovo-vegetarian | 4 | 1.2% | |

| Lacto-vegetarian | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Lacto-ovo vegetarian | 8 | 2.3% | |

| Bodhi vegetarian | 9 | 2.6% | |

| Religious belief | Non-religious | 143 | 41.9% |

| Folk religion | 41 | 12.0% | |

| Buddhism | 77 | 22.6% | |

| Taoism | 55 | 16.1% | |

| Catholicism | 2 | 0.6% | |

| Christianity | 17 | 5.0% | |

| Other | 6 | 1.8% |

| Variables | Items | Standardized Factor Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | Green values | 1. I consider cage-free eggs to be environmentally friendly products. | 0.714 *** | 0.783 | 0.644 | 0.881 |

| 2. I think buying cage-free eggs helps the environment stay sustainable by reducing carbon emissions. | 0.762 *** | |||||

| 3. I consider cage-free eggs more eco-friendly than eggs from other farming methods. | 0.802 *** | |||||

| 4. I believe that cage-free eggs meet my expectations for promoting environmental sustainability. | 0.792 *** | |||||

| Ethical values | 1. I consider it morally correct to purchase cage-free eggs. | 0.816 *** | ||||

| 2. I would feel guilty if I purchased eggs from inhumane farming practices. | 0.837 *** | |||||

| 3. I believe that purchasing cage-free eggs is aligned with my principles. | 0.803 *** | |||||

| Attitude towards cage-free eggs | 1. I am very interested in cage-free eggs. | 0.885 *** | 0.864 | 0.681 | 0.857 | |

| 2. I believe cage-free eggs are beneficial to me. | 0.815 *** | |||||

| 3. I would like to learn more about cage-free eggs. | 0.771 *** | |||||

| Behavioral intention | 1. I will prioritize purchasing cage-free eggs. | 0.896 *** | 0.942 | 0.802 | 0.941 | |

| 2. I would tell my family and friends about the advantages and disadvantages of cage-free eggs. | 0.852 *** | |||||

| 3. I will recommend cage-free eggs to others. | 0.921 *** | |||||

| 4. In the future, I intend to frequently purchase cage-free eggs. | 0.912 *** | |||||

| Human–nature connectedness | 1. I believe humans are an integral part of nature. | 0.791 *** | 0.875 | 0.699 | 0.872 | |

| 2. I think humans depend on the natural environment to survive. | 0.863 *** | |||||

| 3. I think that safeguarding the environment is vital for future generations. | 0.853 *** | |||||

| Trust in labels | 1. I trust that cage-free eggs with certified labels offer better quality assurance. | 0.868 *** | 0.932 | 0.774 | 0.930 | |

| 2. I find peace of mind in knowing that eggs are produced on farms with humane management practices. | 0.904 *** | |||||

| 3. I consider farms with certified labels for cage-free eggs to be trustworthy. | 0.919 *** | |||||

| 4. I believe that the traceability of certified cage-free eggs ensures the accountability for any issues. | 0.824 *** | |||||

| Attitude towards animal welfare | 1. Valuing animal welfare makes me feel good. | 0.846 *** | 0.945 | 0.711 | 0.945 | |

| 2. I believe that animal welfare is essential to the environment. | 0.891 *** | |||||

| 3. I believe that animal welfare is important for food safety. | 0.873 *** | |||||

| 4. I think economic animals should be treated better. | 0.784 *** | |||||

| 5. I think animal welfare organizations are fundamental in ensuring adequate care for animals used in economic activities. | 0.834 *** | |||||

| 6. I think farms that raise economic animals should receive certification from animal welfare organizations. | 0.853 *** | |||||

| 7. I think legislation should be in place to ensure adequate welfare for economic animals. | 0.818 *** | |||||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Values | 4.9355 | 1.20748 | 0.802 | |||||

| 2. Attitude towards cage-free eggs | 4.7312 | 1.31074 | 0.736 ** | 0.825 | ||||

| 3. Behavioral intention | 4.8387 | 1.40522 | 0.718 ** | 0.764 ** | 0.896 | |||

| 4. Human–nature connectedness | 6.0655 | 1.23799 | 0.547 ** | 0.446 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.836 | ||

| 5. Trust in labels | 5.5696 | 1.25122 | 0.731 ** | 0.699 ** | 0.697 ** | 0.562 ** | 0.880 | |

| 6. Attitude towards animal welfare | 5.6267 | 1.23982 | 0.741 ** | 0.688 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.636 ** | 0.804 ** | 0.843 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Unstandardized Coefficient | S.E. | C.R. | p | Standardized Coefficients | β | Verification Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Values → Attitude towards cage-free eggs | 2.010 | 0.301 | 6.680 | *** | 0.895 | 0.736 | Supported |

| H2: Attitude towards cage-free eggs → Behavioral intention | 0.555 | 0.084 | 6.590 | *** | 0.702 | 0.764 | Supported |

| H3: Human–nature connectedness → Behavioral intention | −0.320 | 0.093 | −3.426 | *** | −0.180 | 0.389 | Unsupported |

| H4: Trust in labels → Behavioral intention | 0.336 | 0.122 | 2.754 | ** | 0.190 | 0.697 | Supported |

| H5: Attitude towards animal welfare → Behavioral intention | 0.614 | 0.134 | 4.591 | *** | 0.346 | 0.711 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, M.-Y.; Chao, C.-T.; Chen, H.-S. Exploring the Impact of Human–Animal Connections and Trust in Labeling Consumers’ Intentions to Buy Cage-Free Eggs: Findings from Taiwan. Foods 2023, 12, 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12173310

Chang M-Y, Chao C-T, Chen H-S. Exploring the Impact of Human–Animal Connections and Trust in Labeling Consumers’ Intentions to Buy Cage-Free Eggs: Findings from Taiwan. Foods. 2023; 12(17):3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12173310

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Min-Yen, Ching-Tzu Chao, and Han-Shen Chen. 2023. "Exploring the Impact of Human–Animal Connections and Trust in Labeling Consumers’ Intentions to Buy Cage-Free Eggs: Findings from Taiwan" Foods 12, no. 17: 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12173310

APA StyleChang, M.-Y., Chao, C.-T., & Chen, H.-S. (2023). Exploring the Impact of Human–Animal Connections and Trust in Labeling Consumers’ Intentions to Buy Cage-Free Eggs: Findings from Taiwan. Foods, 12(17), 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12173310