The Effect of Vice–Virtue Bundles on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Vice Packaged Foods: Evidence from Randomized Experiments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. Vice and Virtue

2.2. Vice-Packaged Food with Vice–Virtue Bundles and Purchase Intention

2.3. The Moderating Role of Regulatory Focus

3. Experiment 1

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Materials and Procedures

3.2. Results

4. Experiment 2

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Materials and Procedures

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Main Effect

4.2.2. Perceived Healthiness as a Mediator

5. Experiment 3

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Participants

5.1.2. Materials and Procedures

5.2. Results

5.2.1. Main Effect

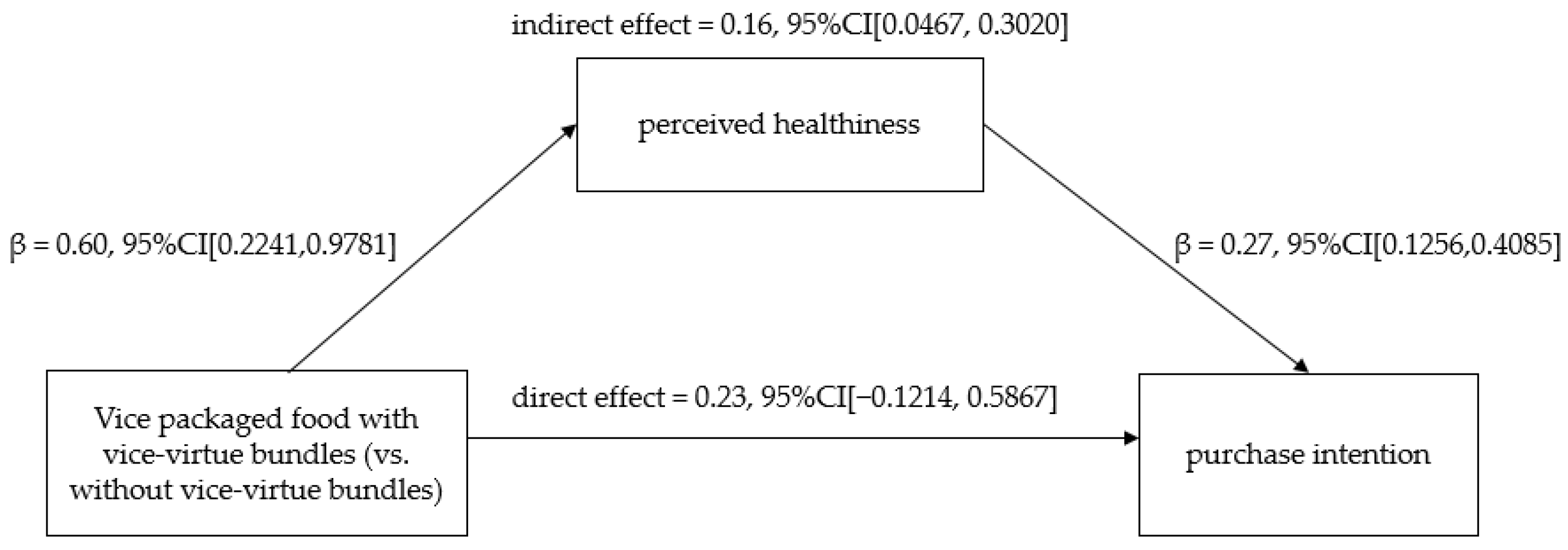

5.2.2. Perceived Healthiness as a Mediator

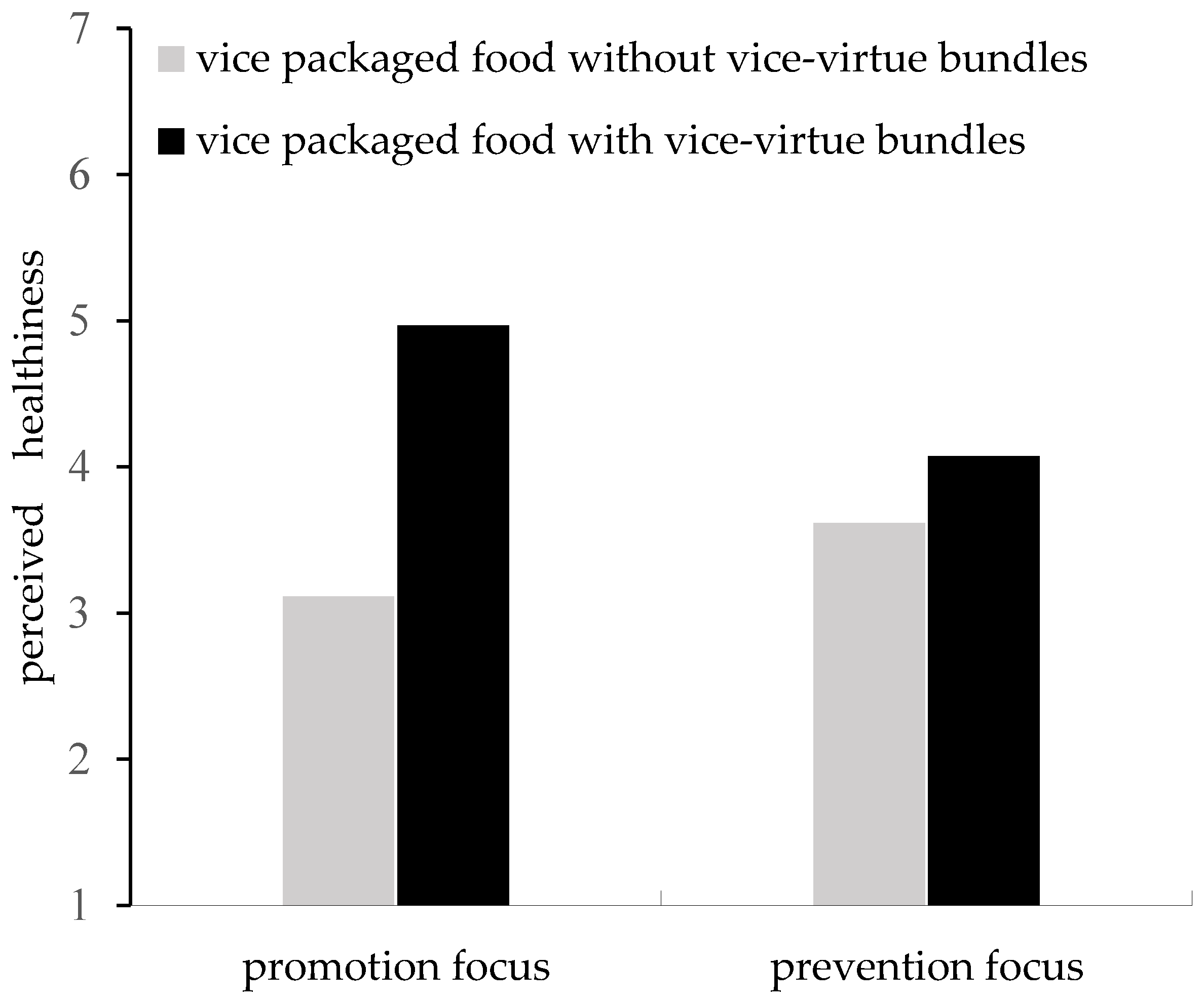

5.2.3. Regulatory Focus as a Moderator

6. General Discussion

6.1. Summary of Findings

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raghunathan, R.; Naylor, R.W.; Hoyer, W.D. The unhealthy equal tasty intuition and its effects on taste inferences, enjoyment, and choice of food products. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A.; Gal, D. Categorization effects in value judgments: Averaging bias in evaluating combinations of vices and virtues. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P.; Ashmore, M.; Markwith, M. Lay American conceptions of nutrition: Dose insensitivity, categorical thinking, contagion, and the monotonic mind. Health Psychol. 1996, 15, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertenbroch, K. Consumption self-control by rationing purchase quantities of virtue and vice. Mark. Sci. 1998, 17, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lei, J. The effect of food toppings on calorie estimation and consumption. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.J.; Haws, K.L.; Lamberton, C.; Campbell, T.H.; Fitzsimons, G.J. Vice-Virtue bundles. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Mathmann, F.; Jin, H.S.; Higgins, E.T. How regulatory focus-mode fit impacts variety-seeking. J. Consum. Psychol. 2023, 33, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.C.; Park, J.; Nayakankuppam, D. The influence of mindset abstraction on preference for mixed versus ex-treme approaches to multigoal pursuits. J. Consum. Psycho. 2023, 33, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, B.; Levy, A.S.; Derby, B.M. The impact of health claims on consumer search and product evaluation outcomes: Results from FDA experimental data. J. Public Policy Mark. 1999, 18, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.; Jostmann, N.B.; Wiers, R.W.; Holland, R.W. Approach avoidance training in the eating domain: Testing the effectiveness across three single session studies. Appetite 2015, 85, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, H.; Shu, L. Simple or complex: How temporal landmarks shape consumer preference for food packages. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Varela, F.; Machin, L.; Antunez, L.; Gimenez, A.; Curutchet, M.R.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Comparative performance of three interpretative front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes: Insights for policy making. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Benoit-Moreau, F.; Russell, C.A. Can evoking nature in advertising mislead consumers? The power of ‘executional greenwashing’. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ooijen, I.; Fransen, M.L.; Verlegh, P.W.J.; Smit, E.G. Signalling product healthiness through symbolic package cues: Effects of package shape and goal congruence on consumer behaviour. Appetite 2017, 109, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.O.; Guyt, J.Y. A War on sugar? Effects of reduced sugar content and package size in the soda category. J. Mark. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.L.; Liberman, N.; Salovey, P.; Higgins, E.T. When to begin? Regulatory focus and initiating goal pursuit. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmani, A.; Zhu, R. Vigilant against manipulation: The effect of regulatory focus on the use of persuasion knowledge. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, D.; Loewenstein, G.; Kalyanaraman, S. Mixing virtue and vice: Combining the immediacy effect and the diversification heuristic. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1999, 12, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.G.; Xu, Q.; Jin, L.Y. Sweet or sweat, which should come first: How consumption sequences of vices and virtues influence enjoyment. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, T.M.; Mishra, A. The influence of hero and villain labels on the perception of vice and virtue products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2019, 29, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Guha, A.; Biswas, A. Investigating the pleasures of sin: The contingent role of arousal-seeking disposition in consumers’ evaluations of vice and virtue product offerings. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, S.K.; Liu, P.J.; Ubel, P.A. Don’t count calorie labeling out: Calorie counts on the left side of menu items lead to lower calorie food choices. J. Consum. Psychol. 2019, 29, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, I.; Sotgiu, F.; Aydinli, A.; Verlegh, P.W.J. Consumer effects of front-of-package nutrition labeling: An interdisciplinary meta-analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 360–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Chandon, P. Can “Low-Fat” nutrition labels lead to obesity? J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinoglu, N.Z.; Krishna, A. Guiltless gluttony: The asymmetric effect of size labels on size perceptions and consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 37, 1095–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, C.; Sá, A.G.A.; Ribeiro Gagliardi, T.; dos Santos Alves, M.J.; Ayala Valencia, G. Understanding the packaging colour on consumer perception of plant-based hamburgers: A preliminary study. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2023, 36, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Pang, J.; Koo, M.; Patrick, V.M. Shape matters: Package shape informs brand status categorization and brand choice. J. Retail. 2020, 96, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.C.; Guo, X.Y.; Huang, J.P.; Wan, X.A. Expectations generated based on associative learning guide visual search for novel packaging labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Rishika, R.; Janakiraman, R.; Kannan, P.K. Competitive effects of front-of-package nutrition labeling adoption on nu tritional quality: Evidence from facts up front-style labels. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, M.Y.A.; Pontes, N.; France, C. The influence of health star rating labels on plant-based foods: The moderating role of con sumers’ believability. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 107, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Gao, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Monahan, F.J. The effects of nutrition and health claim information on consumers’ sensory preferences and willingness to pay. Foods 2022, 11, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, C.; Embling, R.; Neilson, L.; Randall, T.; Wakeham, C.; Lee, M.D.; Wilkinson, L.L. Consumer knowledge and acceptance of “Algae” as a protein alternative: A UK-based qualitative study. Foods 2022, 11, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goukens, C.; Klesse, A.K. Internal and external forces that prevent (vs. Facilitate) healthy eating: Review and outlook within consumer Psychology. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 46, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernev, A. Semantic anchoring in sequential evaluations of vices and virtues. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 37, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, J.; Grant, H.; Idson, L.C.; Higgins, E.T. Success/failure feedback, expectancies, and approach/avoidance motivation: How regulatory focus moderates classic relations. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 37, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Cornwell, J.F. Securing foundations and advancing frontiers: Prevention and promotion effects on judgment & decision making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 2016, 136, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Nakkawita, E.; Rossignac-Milon, M.; Pinelli, F.; Jun, Y.J. Making the right decision: Intensifying the worth of a chosen option. J. Consum. Psychol. 2020, 30, 712–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.J.; Sun, H.Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.P. Guess who buys cheap? The effect of consumers’ goal orientation on product preference. J. Consum. Psychol. 2020, 30, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Naidoo, V. The impact of regulatory focus and word of mouth valence on search and experience attribute evaluation. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 1353–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pula, K.; Parks, C.D.; Ross, C.F. Regulatory focus and food choice motives. Prevention orientation associated with mood, conven ience, and familiarity. Appetite 2014, 78, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichierri, M.; Pino, G.; Peluso, A.M.; Guido, G. The interplay between health claim type and individual regulatory focus in deter mining consumers’ intentions toward extra-virgin olive oil. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using. G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, L.; Krishna, A.; McFerran, B. Rejecting responsibility: Low physical involvement in obtaining food promotes unhealthy eating. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E.T.; Friedman, R.S.; Harlow, R.E.; Idson, L.C.; Ayduk, O.N.; Taylor, A. Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, P.; Wansink, B. The biasing health halos of fast-food restaurant health claims: Lower calorie estimates and higher side-dish consumption intentions. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, A.; Lagana, V.R.; Di Gregorio, D. Habits, health and environment in the purchase of bakery products: Consumption preferences and sustainable inclinations before and during COVID-19. Foods 2023, 12, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, S.T.; Yip, L.S. The moderator effect of monetary sales promotion on the relationship between brand trust and purchase behaviour. J. Brand Manag. 2008, 15, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; Kou, S.; Hou, Y. The role of awe on booking intention in short-term rentals. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.J.; Haws, K.L.; Scherr, K.; Redden, J.P.; Bettman, J.R.; Fitzsimons, G.J. The primacy of “What” over “How Much”: How type and quantity shape healthiness perceptions of food portions. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 3353–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Yan, H.; Pan, L.; Li, O. Bring it on! Package shape signaling dominant male body promotes healthy food consumption for male consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.G.; Cardoso, S.; Bettencourt, A.F.; Ribeiro, I.A. Latest trends in sustainable polymeric food packaging films. Foods 2022, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedi-Firoozjah, R.; Salim, S.A.; Hasanvand, S.; Assadpour, E.; Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Jafari, S.M. Application of smart packaging for seafood: A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1438–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.; Capelli, S. Increasing purchase intention while limiting binge-eating: The role of repeating the same flavor-giving ingredient image on a front of package. Psychol. Mark. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Burzynska, J.; Wang, Q.J.; Spence, C.; Bastian, S.E.P. Taste the bass: Low frequencies increase the perception of body and aromatic intensity in red wine. Multisens. Res. 2019, 32, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.; Taylor, A.; Roberts, D. Psychological processes in flavour perception. Flavour Percept. 2004, 5, 256–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, R.; Díaz, O.; Ronceros, B.; Pedreschi, F.; Aguilera, J.M. Description of the kinetic enzymatic browning inbanana (Musa cavendish) slices using non-uniform color information from digital images. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Duerlund, M.; Bøegh-Petersen, J.; Bredie, W.L.; Frøst, M.B. Stimulus collative properties and con-sumers’ flavor preferences. Appetite 2014, 77, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goor, D.; Keinan, A.; Ordabayeva, N. Status pivoting. J. Consum. Res. 2021, 47, 978–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K. The resurgence of awe in psychology: Promise, hope, and perils. Humanist. Psychol. 2017, 45, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ocampo, J.; Jin, G. Awe, daily stress, and elevated life satisfaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 120, 837–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.N.; Li, F.G. Does ‘chicken soup for the soul’ on the product packaging work? The mediating role of perceived warmth and self-brand connection. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilicic, J.; Brennan, S.M. Shake it off and eat less: Anxiety-inducing product packaging design influences food product interaction and eating. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 562–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Feng, C.; Xiao, X.; Hou, Y. The Effect of Vice–Virtue Bundles on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Vice Packaged Foods: Evidence from Randomized Experiments. Foods 2023, 12, 3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12173270

Yu Y, Sun Z, Feng C, Xiao X, Hou Y. The Effect of Vice–Virtue Bundles on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Vice Packaged Foods: Evidence from Randomized Experiments. Foods. 2023; 12(17):3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12173270

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Yating, Zhaoyang Sun, Chao Feng, Xiang Xiao, and Yubo Hou. 2023. "The Effect of Vice–Virtue Bundles on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Vice Packaged Foods: Evidence from Randomized Experiments" Foods 12, no. 17: 3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12173270

APA StyleYu, Y., Sun, Z., Feng, C., Xiao, X., & Hou, Y. (2023). The Effect of Vice–Virtue Bundles on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Vice Packaged Foods: Evidence from Randomized Experiments. Foods, 12(17), 3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12173270