Red and Processed Meat Consumption in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Household Budget Survey Data Characteristics

2.1.1. Household Budget Survey Selection and Sample

2.1.2. Household Budget Survey Methodology Aspects

2.1.3. Meat Consumption Data

2.2. Data from Nationwide Dietary Survey in Poland

2.2.1. Study Population

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

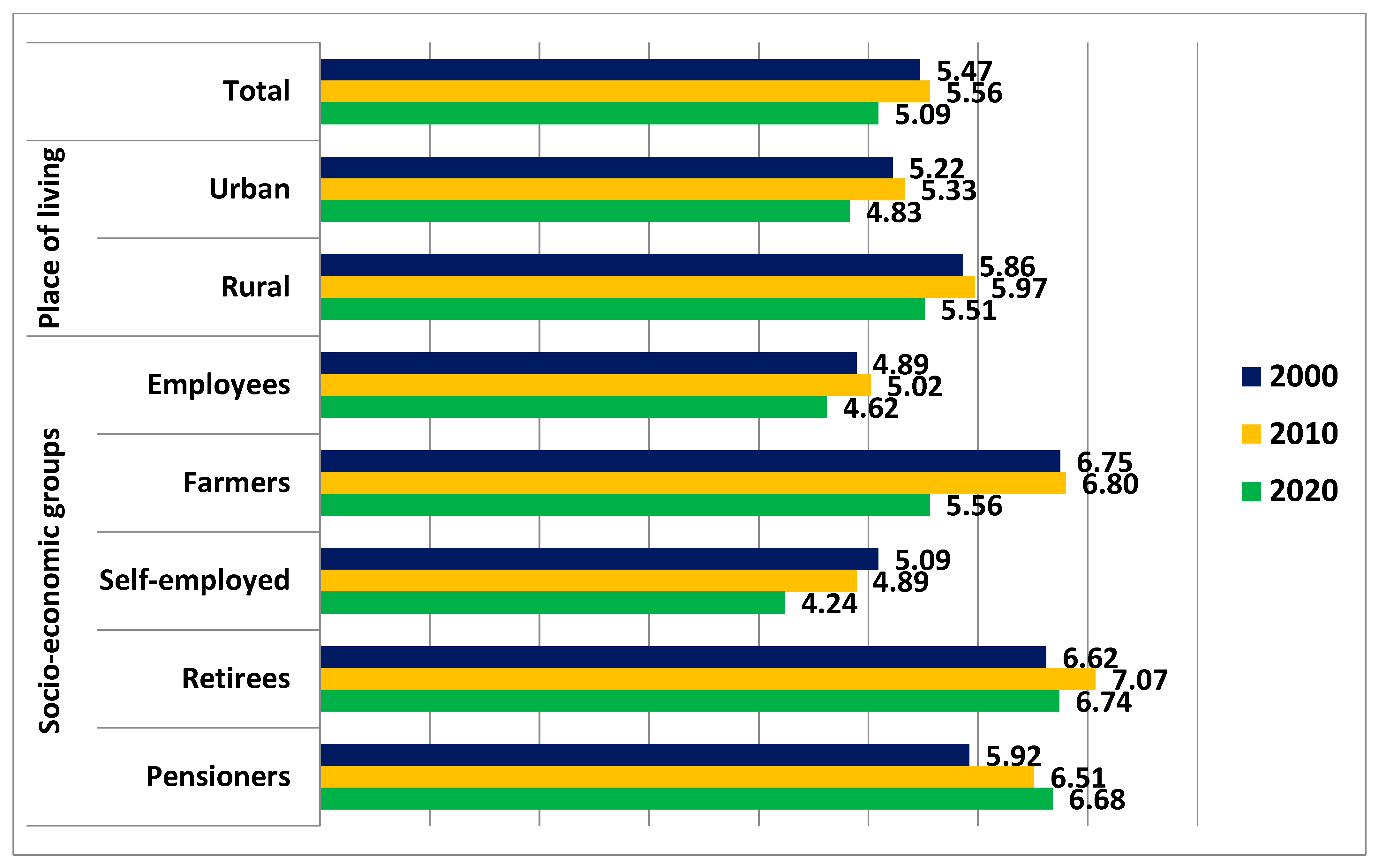

3.1. Results of Meat and Meat Product Consumption from Household Budget Survey

3.2. Results of Nationwide Dietary Survey in Poland

3.2.1. Subject Characteristics

3.2.2. Frequency of Meat and Meat Product Consumption during the 12 Months Prior to the Study

3.2.3. Relationships between Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Health Status, and Frequency of Consumption of Selected Types of Meat and Meat Products

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kunachowicz, H.; Nadolna, I.; Przygoda, B.; Iwanow, K. Tabele Składu i Wartości Odżywczej Żywności [Food Composition Tables]; Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens); Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; Mc Ardle, H.J.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the scientific advice related to nutrient profiling for the development of harmonised mandatory front-of-pack nutrition labelling and the setting of nutrient profiles for restricting nutrition and health claims on foods. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papier, K.; Knuppel, A.; Syam, N.; Jebb, S.A.; Key, T.J. Meat consumption and risk of ischemic heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, S.P.; Mejborn, H.; Christensen, A.I.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Thygesen, L.C. Meat consumption, stratified by dietary quality, and risk of heart disease. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 1881–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Satija, A.; Blondin, S.A.; Janiszewski, M.; Emlen, E.; O’Connor, L.E.; Campbell, W.W.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; Stampfer, M.J. Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials of Red Meat Consumption in Comparison With Various Comparison Diets on Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Circulation 2019, 139, 1828–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Fu, J.; Moore, J.B.; Stoner, L.; Li, R. Processed and Unprocessed Red Meat Consumption and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, D.; Wang, D.; Campos, H.; Baylin, A. Red meat consumption and metabolic syndrome in the Costa Rica Heart Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micha, R.; Wallace, S.K.; Mozaffarian, D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2010, 121, 2271–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, R.; Dehghan, M.; Mente, A.; Rangarajan, S.; Wielgosz, A.; Avezum, A.; Seron, P.; Al Habib, K.F.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Swaminathan, S.; et al. Associations of unprocessed and processed meat intake with mortality and cardiovascular disease in 21 countries [Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study]: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Cao, D.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Li, J.; Guo, J.; Dong, Q.; Liu, L.; Wei, Q. Red and processed meat consumption and cancer outcomes: Umbrella review. Food Chem. 2021, 356, 129697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farvid, M.S.; Sidahmed, E.; Spence, N.D.; Mante Angua, K.; Rosner, B.A.; Barnett, J.B. Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). Red Meat and Processed Meat Volume 114. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; IARC: Lyon, France, 2018; Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono114.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute of Cancer Research. Recommendations and Public Health and Policy Implications. 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Recommendations.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- European Commission 2020. Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. 2020. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-05/f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; De Clerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S.A. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018, 361, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Sharma, P.; Shu, S.; Lin, T.; Ciais, P.; Tubiello, F.N.; Smith, P.; Campbell, N.; Jain, A.K. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, D.; Bogueva, D. Food in a Planetary Emergency; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–232. [Google Scholar]

- Salter, A.M. The effects of meat consumption on global health. Rev. Sci. Technol. 2018, 37, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animal Agriculture Wastes One-Third of Drinkable Water (and 8 Other Facts for World Water Day). Available online: https://mercyforanimals.org/blog/animal-agriculture-wastes-one-third-of-drinkable/ (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Gerbens-Leenes, P.W.; Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The water footprint of poultry, pork and beef: A comparative study in different countries and production systems. Water Resour. Ind. 2013, 1–2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livestock Water Requirements and Water Budgeting for South-West Western Australia. Available online: https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/small-landholders-western-australia/livestock-water-requirements-and-water-budgeting-south-west (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Koch, F.; Heuer, T.; Krems, C.; Claupein, E. Meat consumers and non-meat consumers in Germany: A characterisation based on results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. J. Nutr. Sci. 2019, 8, E21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einhorn, L. Meat consumption, classed? The socioeconomic underpinnings of dietary change. Österreich. Z. Soziol. 2021, 46, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossard, M.H.; York, R. Social Structural Influences on Meat Consumption. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2003, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland. Household Budget Survey 2020; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2021.

- EFSA. General principles for the collection of national food consumption data in the view of a pan-European dietary survey. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Guidance on the EU menu methodology. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Website of the Republic of Poland. Portal Interoperacyjności i Architektury. Rejestr PESEL. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/ia/rejestr-pesel (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Kissinger, L.; Lorenzana, R.; Mittl, B.; Lasrado, M.; Iwenofu, S.; Olivo, V.; Helba, C.; Capoeman, P.; Williams, A.H. Development of a computer-assisted personal interview software system for collection of tribal fish consumption data. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2010, 30, 1833–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Poland. Stan Zdrowia Ludności Polski w 2019 r. In Health Status of Population in Poland in 2019; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/stan-zdrowia-ludnosci-polski-w-2019-r-,6,7.html (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Wądołowska, L.; Niedźwiecka, E. Kwestionariusz Częstotliwości Spożycia Żywności [Food Frequency Questionnaire with 6 Answers]; Komitet Nauki o Żywieniu Człowieka Polskiej Akademii Nauk (The Committee on Human Nutrition Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences): Olsztyn, Poland, 2009. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ambrus, Á.; Horváth, Z.; Farkas, Z.; Cseh, J.; Petrova, S.; Dimitrov, P.; Duleva, V.; Rangelova, L.; Chikova-Iscener, E.; Ovaskainen, M.-L.; et al. Pilot study in the view of a Pan-European dietary survey—Adolescents, adults and elderly. EFSA Support. Publ. 2013, 10, 508E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolnicka, K. Talerz Zdrowego Żywienia [Plate of Healthy Eating]. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/abc-zywienia/talerz-zdrowego-zywienia/ (accessed on 16 August 2022). (In Polish)

- Krittanawong, C.; Isath, A.; Hahn, J.; Wang, Z.; Narasimhan, B.; Kaplin, S.L.; Jneid, H.; Virani, S.S.; Tang, W.H.W. Fish Consumption and Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Med. 2021, 134, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahab, F.; Pearson, K.; Frankel, M.R.; Ard, J.; Safford, M.M.; Kleindorfer, D.; Howard, V.J.; Judd, S. Dietary fried fish intake increases risk of CVD: The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 3327–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoś, K.; Rychlik, E.; Woźniak, A.; Ołtarzewski, M.; Wojda, B.; Przygoda, B.; Matczuk, M.; Pietraś, E.; Kłys, W. Krajowe Badanie Sposobu Żywienia i Stanu Odżywienia Populacji Polskiej [National Survey of Dietary Pattern and Nutritional Status of Polish Population]; Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego PZH—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. (In Polish)

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland 2001; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2000; pp. 332–333.

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland 2011; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; pp. 441–442.

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland 2021; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; p. 456.

- Jarosz, M. (Ed.) Praktyczny Podręcznik Dietetyki [Practical Dietetics Manual]; Institute of Food and Nutrition: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Whitton, C.; Bogueva, D.; Marinova, D.; Phillips, C.J.C. Are We Approaching Peak Meat Consumption? Analysis of Meat Consumption from 2000 to 2019 in 35 Countries and Its Relationship to Gross Domestic Product. Animals 2021, 11, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.; Piernas, C.; Cook, B.; Jebb, S.A. Trends in UK meat consumption: Analysis of data from years 1-11 (2008-09 to 2018-19) of the National Diet and Nutrition Survey rolling programme. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5, e699–e708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Ruan, M.; Liu, J.; Wilde, P.; Naumova, E.N.; Mozaffarian, D.; Zhang, F.F. Trends in Processed Meat, Unprocessed Red Meat, Poultry, and Fish Consumption in the United States, 1999–2016. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2019, 119, 1085–1098.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocking, C.; Walton, J.; Kehoe, L.; Cashman, K.D.; Flynn, A. The role of meat in the European diet: Current state of knowledge on dietary recommendations, intakes and contribution to energy and nutrient intakes and status. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2020, 33, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szałajko, M.; Stachowicz, W.; Dobosz, M.; Szałankiewicz, M.; Sokal, A.; Łuszczki, E. Nutrition habits and frequency of consumption of selected food products by the residents of urban and rural area from the Subcarpathian voivodeship. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2021, 72, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.M.; Jaacks, L.M.; Batis, C.; Vanderlee, L.; Taillie, L.S. Patterns of Red and Processed Meat Consumption across North America: A Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Comparison of Dietary Recalls from Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śniadaniowe Nawyki. 88% Polaków Upodobało Sobie Jeden Poranny Posiłek. Jaki? [Breakfast Habits. 88% of Poles like one Morning Meal. What?]. Available online: https://wiadomoscispozywcze.pl/artykuly/9385/sniadaniowe-nawyki-88-polakow-upodobao-sobie-jeden-poranny-posiek-jaki/ (accessed on 11 October 2022). (In Polish).

- Świstak, E.; Laskowski, W. Zmiany wzorca konsumpcji żywności na wsi i ich uwarunkowania [Food consumption changes in rural areas and their determinants]. Zesz. Nauk. Szkoły Głównej Gospod. Wiej. Ekon. I Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2016, 114, 5–17. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkowska, K.; Piekut, M. Konsumpcja w wiejskich gospodarstwach domowych [Consumption in rural households]. Wieś I Rol. 2014, 165, 159–178. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kirbiš, A.; Lamot, M.; Javornik, M. The Role of Education in Sustainable Dietary Patterns in Slovenia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Meat | Year | Total | Place of Living | Socioeconomic Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Employees | Farmers | Self- Employed | Retirees | Pensioners | |||

| Raw red meat | 2000 | 1.73 | 1.62 | 1.90 | 1.53 | 2.49 | 1.70 | 2.02 | 1.75 |

| 2010 | 1.57 | 1.47 | 1.74 | 1.40 | 2.36 | 1.45 | 1.95 | 1.64 | |

| 2020 | 1.35 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.19 | 1.61 | 1.13 | 1.85 | 1.72 | |

| Processed red meat products | 2000 | 1.90 | 1.85 | 1.96 | 1.80 | 2.05 | 1.77 | 2.19 | 1.99 |

| 2010 | 1.97 | 1.92 | 2.04 | 1.82 | 2.17 | 1.71 | 2.42 | 2.22 | |

| 2020 | 1.75 | 1.68 | 1.84 | 1.61 | 1.82 | 1.45 | 2.25 | 2.23 | |

| Raw red meat and processed red meat products | 2000 | 3.63 | 3.47 | 3.86 | 3.33 | 4.54 | 3.47 | 4.21 | 3.74 |

| 2010 | 3.54 | 3.39 | 3.78 | 3.22 | 4.53 | 3.16 | 4.37 | 3.86 | |

| 2020 | 3.10 | 2.93 | 3.34 | 2.80 | 3.43 | 2.58 | 4.10 | 3.95 | |

| Raw poultry meat | 2000 | 1.34 | 1.25 | 1.49 | 1.12 | 1.70 | 1.21 | 1.71 | 1.56 |

| 2010 | 1.52 | 1.46 | 1.62 | 1.36 | 1.67 | 1.33 | 2.00 | 1.98 | |

| 2020 | 1.55 | 1.47 | 1.70 | 1.42 | 1.67 | 1.34 | 2.02 | 2.09 | |

| Poultry processed meat products | 2000 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| 2010 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.26 | |

| 2020 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.27 | |

| Red and poultry processed meat products | 2000 | 2.04 | 2.01 | 2.08 | 1.95 | 2.13 | 1.92 | 2.38 | 2.13 |

| 2010 | 2.19 | 2.14 | 2.27 | 2.03 | 2.37 | 1.91 | 2.67 | 2.48 | |

| 2020 | 1.96 | 1.89 | 2.05 | 1.82 | 2.01 | 1.63 | 2.47 | 2.50 | |

| Offal and processed offal products | 2000 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| 2010 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.41 | |

| 2020 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.37 | |

| Parameter | Total (n = 1651) | Men (n = 812) | Women (n = 839) | M vs. W | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |

| Education level: | |||||||

| Primary education/lower secondary education | 169 | 10.2 | 82 | 10.1 | 87 | 10.4 | <0.0001 |

| Vocational education | 552 | 33.4 | 321 | 39.5 | 231 | 27.5 | |

| Upper secondary education | 688 | 41.7 | 333 | 41.0 | 355 | 42.3 | |

| Post-secondary education | 44 | 2.7 | 9 | 1.1 | 35 | 4.2 | |

| Higher education | 198 | 12.0 | 67 | 8.3 | 131 | 15.6 | |

| Economic status: | |||||||

| Very bad | 10 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.6 | 0.0600 |

| Bad | 102 | 6.2 | 37 | 4.6 | 65 | 7.8 | |

| Neither good nor bad | 898 | 54.4 | 462 | 56.9 | 436 | 52.0 | |

| Good | 572 | 34.7 | 276 | 34.0 | 296 | 35.3 | |

| Very good | 69 | 4.2 | 67 | 8.3 | 37 | 4.4 | |

| Health status: | |||||||

| Very bad | 6 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.4 | 0.9712 |

| Bad | 63 | 3.8 | 33 | 4,1 | 30 | 3.6 | |

| Neither good nor bad | 576 | 34.9 | 287 | 35.4 | 289 | 34.5 | |

| Good | 709 | 42.9 | 346 | 42.6 | 363 | 43.3 | |

| Very good | 297 | 18.0 | 143 | 17.6 | 154 | 18.4 | |

| Type of Meat | Sex | Frequency of Consumption | M vs. W | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Less than Once a Month | 1–3 Times a Month | Once a Week | 2–3 Times a Week | 4–5 Times a Week | Once a Day | Several Times a Day | * p | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Beef, veal, and mutton | Total | 289 | 17.6 | 477 | 29.1 | 453 | 27.6 | 297 | 18.1 | 97 | 5.9 | 23 | 1.4 | 4 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Men | 140 | 17.3 | 220 | 27.2 | 229 | 28.3 | 150 | 18.5 | 55 | 6.8 | 13 | 1.6 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.5374 | |

| Women | 149 | 17.9 | 257 | 30.9 | 224 | 26.9 | 147 | 17.6 | 42 | 5.0 | 10 | 1.2 | 3 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 | ||

| Pork | Total | 32 | 1.9 | 53 | 3.2 | 187 | 11.4 | 613 | 37.3 | 657 | 40.0 | 87 | 5.3 | 13 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Men | 12 | 1.5 | 20 | 2.5 | 82 | 10.1 | 263 | 32.5 | 373 | 46.0 | 52 | 6.4 | 7 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 | <0.0001 | |

| Women | 20 | 2.4 | 33 | 4.0 | 105 | 12.6 | 350 | 42.0 | 284 | 34.1 | 35 | 4.2 | 6 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Poultry | Total | 6 | 0.4 | 12 | 0.7 | 61 | 3.7 | 365 | 22.1 | 973 | 59.0 | 201 | 12.2 | 29 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Men | 2 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.7 | 33 | 4.1 | 166 | 20.5 | 483 | 59.6 | 105 | 12.9 | 14 | 1.7 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.5273 | |

| Women | 4 | 0.5 | 6 | 0.7 | 28 | 3.3 | 199 | 23.7 | 490 | 58.5 | 96 | 11.5 | 15 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Cold cuts, such as: ham, loin | Total | 44 | 2.7 | 41 | 2.5 | 75 | 4.6 | 257 | 15.6 | 623 | 37.8 | 391 | 23.7 | 143 | 8.7 | 73 | 4.4 | |

| Men | 18 | 2.2 | 21 | 2.6 | 34 | 4.2 | 123 | 15.2 | 294 | 36.3 | 206 | 25.4 | 79 | 9.7 | 36 | 4.4 | 0.4387 | |

| Women | 26 | 3.1 | 20 | 2.4 | 41 | 4.9 | 134 | 16.0 | 329 | 39.4 | 185 | 22.1 | 64 | 7.7 | 37 | 4.4 | ||

| Sausages and bacon | Total | 46 | 2.8 | 110 | 6.7 | 242 | 14.7 | 418 | 25.4 | 575 | 34.9 | 188 | 11.4 | 60 | 3.6 | 7 | 0.4 | |

| Men | 10 | 1.2 | 38 | 4.7 | 81 | 10.0 | 186 | 22.9 | 334 | 41.2 | 118 | 14.6 | 40 | 4.9 | 4 | 0.5 | <0.0001 | |

| Women | 36 | 4.3 | 72 | 8.6 | 161 | 19.3 | 232 | 27.8 | 241 | 28.9 | 70 | 8.4 | 20 | 2.4 | 3 | 0.4 | ||

| Type of Meat | Parameter | Sex * | Age | Education Level | Economic Status | Health Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Rs | p | rs | p | rs | p | rs | p | rs | p | |

| Beef, veal, and mutton | Total | −0.0395 | 0.1092 | −0.0146 | 0.5544 | 0.0529 | 0.0320 | 0.0799 | 0.0012 | 0.0430 | 0.0814 |

| Men | −0.0116 | 0.7413 | 0.0792 | 0.0243 | 0.0922 | 0.0087 | 0.0793 | 0.0242 | |||

| Women | −0.0166 | 0.6318 | 0.0430 | 0.2154 | 0.0691 | 0.0462 | 0.0092 | 0.7906 | |||

| Pork | Total | −0.1391 | <0.0001 | −0.0195 | 0.4295 | −0.0807 | 0.0011 | −0.0005 | 0.9855 | −0.0090 | 0.7156 |

| Men | −0.0967 | 0.0059 | −0.0561 | 0.1105 | −0.0158 | 0.6526 | 0.0318 | 0.3654 | |||

| Women | 0.0563 | 0.1047 | −0.0697 | 0.0443 | 0.0134 | 0.6991 | −0.0443 | 0.2012 | |||

| Poultry | Total | −0.0327 | 0.1848 | −0.1190 | 0.0000 | 0.0147 | 0.5514 | 0.1063 | 0.0000 | 0.0430 | 0.0809 |

| Men | −0.1446 | 0.0000 | −0.0051 | 0.8846 | 0.0675 | 0.0546 | 0.0658 | 0.0612 | |||

| Women | −0.0946 | 0.0061 | 0.0365 | 0.2907 | 0.1414 | 0.0000 | 0.0233 | 0.5006 | |||

| Cold cuts, such as ham, loin | Total | −0.0501 | 0.0419 | −0.1053 | 0.0000 | 0.0308 | 0.2119 | 0.1274 | <0.0001 | 0.1355 | <0.0001 |

| Men | −0.1191 | 0.0007 | 0.0190 | 0.5891 | 0.1502 | 0.0000 | 0.1458 | 0.0000 | |||

| Women | −0.0923 | 0.0076 | 0.0542 | 0.0542 | 0.1060 | 0.0021 | 0.1264 | 0.0002 | |||

| Sausages and bacon | Total | −0.2291 | <0.0001 | 0.0045 | 0.8538 | −0.1138 | 0.0000 | 0.0018 | 0.9426 | 0.0009 | 0.9697 |

| Men | −0.0492 | 0.1619 | −0.0798 | 0.0231 | −0.0437 | 0.2139 | 0.0210 | 0.5494 | |||

| Women | 0.0618 | 0.0744 | −0.0903 | 0.0090 | 0.0409 | 0.2381 | −0.0158 | 0.6477 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoś, K.; Rychlik, E.; Woźniak, A.; Ołtarzewski, M. Red and Processed Meat Consumption in Poland. Foods 2022, 11, 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11203283

Stoś K, Rychlik E, Woźniak A, Ołtarzewski M. Red and Processed Meat Consumption in Poland. Foods. 2022; 11(20):3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11203283

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoś, Katarzyna, Ewa Rychlik, Agnieszka Woźniak, and Maciej Ołtarzewski. 2022. "Red and Processed Meat Consumption in Poland" Foods 11, no. 20: 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11203283

APA StyleStoś, K., Rychlik, E., Woźniak, A., & Ołtarzewski, M. (2022). Red and Processed Meat Consumption in Poland. Foods, 11(20), 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11203283