Impacts of Self-Efficacy on Food and Dietary Choices during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Processing

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

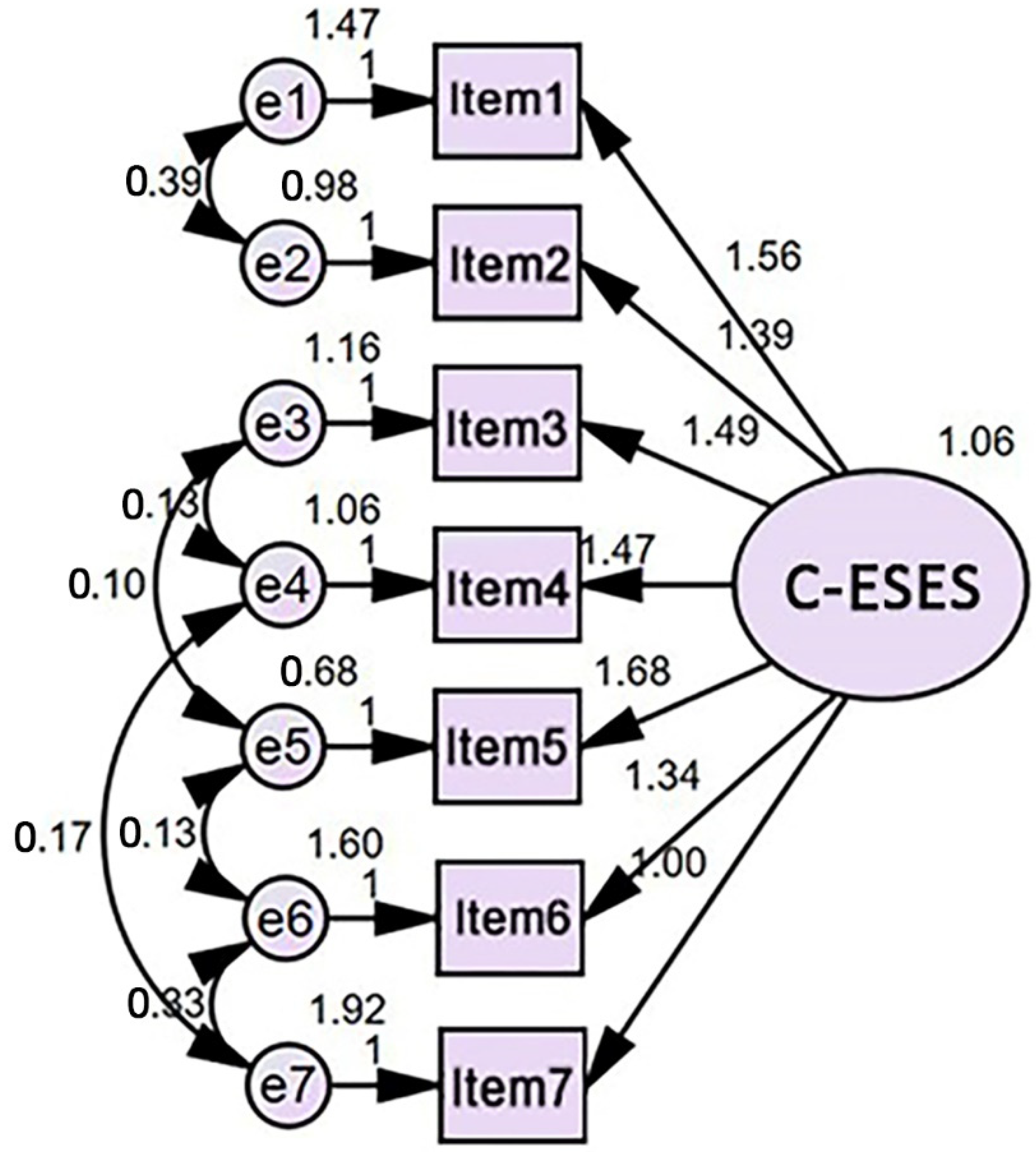

4.2. Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale

4.3. Food Choices

4.4. Socioeconomic Status and Self-Efficacy

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Emotional Self-Efficacy “How do you feel during the COVID-19 pandemic?” (Likert scale: 1 = Never; 7 = All the time)

Diet Quality Index before/during the COVID-19 Lockdown “How often did/do you eat the following (portions of) foods?” (1 = Almost never; 7 = 2x or more times a day) Healthy food

Unhealthy food

Socioeconomic Status Highest education

“Have you lost (a part of your) income since the lockdown?”

“In general, how often is it a struggle to make your money last until the end of the month/payday?”

“In general, how often is it a struggle to have enough money to go shopping for food?”

Gender

(Ranging from 18 to 120) Degree of closure measures “Which of the following lockdown measures are currently in place?” (Multiple choice: 0 = No; 1 = Yes)

“How many weeks have you been in lockdown?” (Ranging from 1 to 50) Food choices influenced by marketing “At the moment (during the lockdown), how often food advertisements or marketing influence your food choices when you go grocery shopping?”

|

Appendix B

| Item | Factor Loadings | Communalities | Item-Total Correlation | α, If Item Deleted | Screening Items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component 1 | Component 2 | |||||

| 1. I feel hopeless | 0.823 | −0.254 | 0.741 | 0.663 | 0.896 | Retain |

| 2. I feel restless or fidgety | 0.850 | −0.165 | 0.749 | 0.690 | 0.893 | Retain |

| 3. I feel that everything requires effort | 0.501 | 0.651 | 0.675 | 0.309 | 0.916 | Exclude |

| 4. I feel worthless | 0.818 | −0.300 | 0.758 | 0.656 | 0.896 | Retain |

| 5. I feel nervous | 0.847 | −0.112 | 0.730 | 0.662 | 0.893 | Retain |

| 6. I feel so depressed | 0.880 | −0.237 | 0.831 | 0.755 | 0.890 | Retain |

| 7. I feel I have more time than usual | 0.574 | 0.632 | 0.729 | 0.399 | 0.912 | Exclude |

| 8. I feel I struggle financially | 0.803 | −0.011 | 0.644 | 0.573 | 0.896 | Retain |

| 9. I feel more connected than usual | 0.722 | 0.301 | 0.611 | 0.476 | 0.902 | Retain |

| Item | Mean | SD | Factor Loadings | Communalities | Item-Total Correlation | α, If Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel hopeless | 4.68 | 2.01 | 0.849 | 0.722 | 0.785 | 0.911 |

| 2. I feel restless or fidgety | 4.51 | 1.74 | 0.861 | 0.741 | 0.802 | 0.910 |

| 3. I feel worthless | 4.83 | 1.88 | 0.847 | 0.717 | 0.781 | 0.911 |

| 4. I feel nervous | 4.21 | 1.83 | 0.853 | 0.727 | 0.790 | 0.910 |

| 5. I feel so depressed | 4.56 | 1.92 | 0.903 | 0.815 | 0.855 | 0.903 |

| 6. I feel I struggle financially | 4.39 | 1.87 | 0.800 | 0.640 | 0.727 | 0.917 |

| 7. I feel more connected than usual | 4.01 | 1.72 | 0.690 | 0.476 | 0.604 | 0.928 |

References

- Horton, R. Offline: 2019-nCoV—“A desperate plea”. Lancet 2020, 395, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.; Anseel, F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Bamberger, P.; Bapuji, H.; Bhave, D.P.; Choi, V.K.; et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naja, F.; Hamadeh, R. Nutrition amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-level framework for action. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, T. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active Weibo users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Schulz, P.J.; Tu, S.T.; Liu, M.T. Communicative blame in online communication of the COVID-19 pandemic: Computational approach of stigmatizing cues and negative sentiment gauged with automated analytic techniques. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y. Human mobility restrictions and the spread of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z.; Rahmani, D. Did the COVID-19 lockdown affect consumers’ sustainable behaviour in food purchasing and consumption in China? Food Control 2022, 132, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.Y.; Lin, X.L.; Fang, A.P.; Zhu, H.L. Eating habits and lifestyles during the initial stage of the COVID-19 lockdown in China: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Liu, L.; Xie, X.; Yuan, C.; Chen, H.; Guo, B.; Zhou, J.; Yang, S. Changes in dietary patterns among youths in China during COVID-19 epidemic: The COVID-19 impact on lifestyle change survey (COINLICS). Appetite 2021, 158, 105015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; Li, Z.; Ke, Y.; Huo, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Z. Dietary diversity among Chinese residents during the COVID-19 outbreak and its associated factors. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stookey, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Ge, K.; Lin, H.; Popkin, B.M. Measuring diet quality in China: The INFH-UNC-CH diet quality index. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongprawmas, R.; Mora, C.; Pellegrini, N.; Guiné, R.P.; Carini, E.; Sogari, G.; Vittadini, E. Food choice determinants and perceptions of a healthy diet among Italian consumers. Foods 2021, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Gerbino, M.; Pastorelli, C. Role of affective self-regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, B.A.; Schutte, N.S.; Hine, D.W. Development and preliminary validation of an emotional self-efficacy scale. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2008, 45, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U.; Schwarzer, R. The general self-efficacy scale: Multicultural validation studies. J. Psychol. 2005, 139, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualter, P.; Pool, L.D.; Gardner, K.J.; Ashley-Kot, S.; Wise, A.; Wols, A. The emotional self-efficacy scale: Adaptation and validation for young adolescents. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2015, 33, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.; Kluemper, D.H.; Sauley, K.S. Assessing emotional self-efficacy: Evaluating validity and dimensionality with cross-cultural samples. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 62, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, N. Emotional self-efficacy and positive values. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2018, 4, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Di Giunta, L.; Pastorelli, C.; Eisenberg, N. Mastery of negative affect: A hierarchical model of emotional self-efficacy beliefs. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pool, L.D.; Qualter, P. Improving emotional intelligence and emotional self-efficacy through a teaching intervention for university students. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.S.; Winett, R.A.; Wojcik, J.R. Self-regulation, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and social support: Social cognitive theory and nutrition behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 34, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demakakos, P.; Nazroo, J.; Breeze, E.; Marmot, M. Socioeconomic status and health: The role of subjective social status. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Operario, D.; Adler, N.E.; Williams, D.R. Subjective social status: Reliability and predictive utility for global health. Psychol. Health 2004, 19, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Qin, X. The inequality of nutrition intake among adults in China. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2019, 17, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Hu, J.; Gao, J.; Zhou, Z. Explaining income-related inequalities in dietary knowledge: Evidence from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gómez, G.; Kovalskys, I.; Leme, A.C.B.; Quesada, D.; Rigotti, A.; Cortés Sanabria, L.Y.; Yépez García, M.C.; Liria-Domínguez, M.R.; Herrera-Cuenca, M.; Fisberg, R.M.; et al. Socioeconomic status impact on diet quality and body mass index in eight Latin American countries: ELANS study results. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinai, T.; Axelrod, R.; Shimony, T.; Boaz, M.; Kaufman-Shriqui, V. Dietary patterns among adolescents are associated with growth, socioeconomic features, and health-related behaviors. Foods 2021, 10, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, S.; Gyurak, A.; Levenson, R.W. The ability to regulate emotion is associated with greater well-being, income, and socioeconomic status. Emotion 2010, 10, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgar, F.J.; Pförtner, T.K.; Moor, I.; De Clercq, B.; Stevens, G.W.; Currie, C. Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002–2010: A time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. Lancet 2015, 385, 2088–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.C.; Matthews, K.A. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: Do negative emotions play a role? Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 10–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, F.; Meyrose, A.K.; Otto, C.; Lampert, T.; Klasen, F.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: Results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0213700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, A.S.; Ford, B.Q.; McRae, K.; Zarolia, P.; Mauss, I.B. Change the things you can: Emotion regulation is more beneficial for people from lower than from higher socioeconomic status. Emotion 2017, 17, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Dar, I.A. Emotional intelligence of adolescent students with special reference to high and low socio-economic status. Nat. Sci. 2013, 11, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.; Schulz, P.J.; Jiao, W.; Liu, M.T. Obesity-related communication in digital Chinese news from Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan: Automated content analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e26660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Xian, X.; Liu, M.T.; Zhao, X. Health communication through positive and solidarity messages amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Automated content analysis of Facebook uses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, C.; Teunissen, L.; Cuykx, I.; Decorte, P.; Pabian, S.; Gerritsen, S.; Matthys, C.; Al Sabbah, H.; Van Royen, K.; Corona Cooking Survey Study Group. An evaluation of the COVID-19 pandemic and perceived social distancing policies in relation to planning, selecting, and preparing healthy meals: An observational study in 38 countries worldwide. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, 621726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen, S.; Egli, V.; Roy, R.; Haszard, J.; De Backer, C.; Teunissen, L.; Cuykx, I.; Decorte, P.; Pabian Pabian, S.; Van Royen, K.; et al. Seven weeks of home-cooked meals: Changes to New Zealanders’ grocery shopping, cooking and eating during the COVID-19 lockdown. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2021, 51, S4–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkerwi, A. Diet quality concept. Nutrition 2014, 30, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Costanzo, S.; Ruggiero, E.; Persichillo, M.; Esposito, S.; Olivieri, M.; Castelnuovo, A.D.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; De Gaetano, G.; et al. Changes in ultra-processed food consumption during the first Italian lockdown following the COVID-19 pandemic and major correlates: Results from two population-based cohorts. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3905–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burggraf, C.; Teuber, R.; Brosig, S.; Meier, T. Review of a priori dietary quality indices in relation to their construction criteria. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Schulz, P.J.; Schirato, T.; Hall, B.J. Implicit messages regarding unhealthy foodstuffs in Chinese television advertisements: Increasing the risk of obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalwood, P.; Marshall, S.; Burrows, T.L.; McIntosh, A.; Collins, C.E. Diet quality indices and their associations with health-related outcomes in children and adolescents: An updated systematic review. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qiu, L.; Sa, R.; Dang, S.; Liu, F.; Xiao, X. Effect of socioeconomic characteristics and lifestyle on BMI distribution in the Chinese population: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.T.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P. A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2001, 23, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Schulz, P.J. The measurements and an elaborated understanding of Chinese eHealth literacy (C-eHEALS) in chronic patients in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diviani, N.; Dima, A.L.; Schulz, P.J. A psychometric analysis of the Italian version of the eHealth literacy scale using item response and classical test theory methods. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Huo, S.; Ke, Y.; Zhao, A. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination status and confidence on dietary practices among Chinese residents. Foods 2022, 11, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H. The impact of COVID-19 on food consumption and dietary quality of rural households in China. Foods 2022, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, E.; Sagastume, D.; Sorić, T.; Brodić, I.; Dolanc, I.; Jonjić, A.; Delale, E.A.; Mavar, M.; Missoni, S.; Čoklo, M.; et al. Food choice motives and COVID-19 in Belgium. Foods 2022, 11, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronto, R.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N. Adolescents’ perspectives on food literacy and its impact on their dietary behaviours. Appetite 2016, 107, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, L.M.Y. Food literacy of adolescents as a predictor of their healthy eating and dietary quality. J. Child Adolesc. Behav. 2017, 5, e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, T.; Hatch, J.; Martin, W.; Higgins, J.W.; Sheppard, R. Food literacy: Definition and framework for action. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel hopeless | 1 | ||||||

| 2. I feel restless or fidgety | 0.768 | 1 | |||||

| 3. I feel worthless | 0.648 | 0.665 | 1 | ||||

| 4. I feel nervous | 0.659 | 0.687 | 0.715 | 1 | |||

| 5. I feel so depressed | 0.712 | 0.738 | 0.771 | 0.752 | 1 | ||

| 6. I feel I struggle financially | 0.606 | 0.609 | 0.624 | 0.581 | 0.704 | 1 | |

| 7. I feel more connected than usual | 0.523 | 0.507 | 0.468 | 0.539 | 0.532 | 0.538 | 1 |

| Emotional Self-Efficacy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Low | High | χ2 |

| 230 (%) | 211 (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 139 (60.4) | 136 (64.5) | 0.76 |

| Male | 91 (39.6) | 75 (35.5) | |

| Highest education | |||

| Below high school diploma | 18 (7.8) | 25 (11.8) | 9.32 |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 92 (40.0) | 57 (27.0) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 80 (34.8) | 91 (43.1) | |

| Master’s degree | 36 (15.7) | 34 (16.1) | |

| Doctorate | 4 (1.7) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Work | 163 (70.9) | 135 (64.0) | 2.38 |

| No work | 67 (29.1) | 76 (36.0) | |

| Income loss due to COVID-19 | |||

| Yes | 154 (67.0) | 101 (47.9) | 16.44 *** |

| No | 76 (33.0) | 110 (52.1) | |

| Category | M (SD) | t440 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| During | Before | ||

| Healthy food | |||

| Fruit | 5.03 (1.56) | 5.02 (1.52) | 0.317 |

| Vegetables | 5.03 (1.39) | 5.08 (1.42) | −0.966 |

| Legumes/pulses | 4.56 (1.40) | 4.59 (1.34) | −0.585 |

| Unsalted nuts or nut spread | 4.41 (1.65) | 4.43 (1.54) | −0.385 |

| Unprocessed fish | 4.17 (1.56) | 4.15 (1.60) | 0.435 |

| Unprocessed poultry | 4.20 (1.59) | 4.15 (1.62) | 0.974 |

| Unprocessed red meat | 4.28 (1.63) | 4.35 (1.63) | −1.356 |

| Unprocessed vegetarian alternative | 4.42 (1.62) | 4.42 (1.60) | 0.118 |

| Whole wheat | 4.29 (1.61) | 4.38 (1.56) | −1.576 |

| Milk | 4.67 (1.47) | 4.62 (1.42) | 0.913 |

| Other dairy products | 4.56 (1.52) | 4.56 (1.53) | 0.041 |

| Plant-based drinks | 4.26 (1.63) | 4.29 (1.65) | −0.596 |

| Non-sugared beverages | 4.90 (1.66) | 4.87 (1.65) | 0.504 |

| Unhealthy food | |||

| Processed meat | 4.35 (1.66) | 4.41 (1.68) | −1.048 |

| Sweet snacks | 4.26 (1.60) | 4.33 (1.51) | −1.281 |

| Salty snacks | 4.08 (1.61) | 4.22 (1.60) | −2.330 * |

| White wheat | 4.36 (1.72) | 4.37 (1.65) | −0.079 |

| Sugared beverages | 4.25 (1.66) | 4.18 (1.60) | 1.221 |

| Alcoholic beverages | 3.81 (1.83) | 3.92 (1.84) | −1.968 * |

| Standardized Effect (β) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Dietary Quality | Emotional Self-Efficacy | Dietary Quality (Total Effect) |

| Control block | |||

| Gender | −0.080 | 0.000 | −0.080 |

| Age a | 0.111 * | 0.213 *** | 0.083 |

| Degree of closure measures | 0.108 * | 0.187 *** | 0.084 |

| Self-reported lockdown time a | 0.000 | 0.176 *** | −0.023 |

| Food choices influenced by marketing | 0.336 *** | −0.280 *** | 0.373 *** |

| Prediction block | |||

| Socioeconomic status | 0.094 * | 0.143 *** | 0.075 |

| Emotional self-efficacy | −0.132 * | _ | _ |

| Explanatory power | |||

| R-squared | 0.137 | 0.399 | 0.126 |

| F-value | 9.791 *** | 47.992 *** | 10.442 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiao, W.; Liu, M.T.; Schulz, P.J.; Chang, A. Impacts of Self-Efficacy on Food and Dietary Choices during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in China. Foods 2022, 11, 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172668

Jiao W, Liu MT, Schulz PJ, Chang A. Impacts of Self-Efficacy on Food and Dietary Choices during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in China. Foods. 2022; 11(17):2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172668

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiao, Wen, Matthew Tingchi Liu, Peter Johannes Schulz, and Angela Chang. 2022. "Impacts of Self-Efficacy on Food and Dietary Choices during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in China" Foods 11, no. 17: 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172668

APA StyleJiao, W., Liu, M. T., Schulz, P. J., & Chang, A. (2022). Impacts of Self-Efficacy on Food and Dietary Choices during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in China. Foods, 11(17), 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172668