Metadiscursive Markers and Text Genre: A Metareview

Abstract

1. Introduction

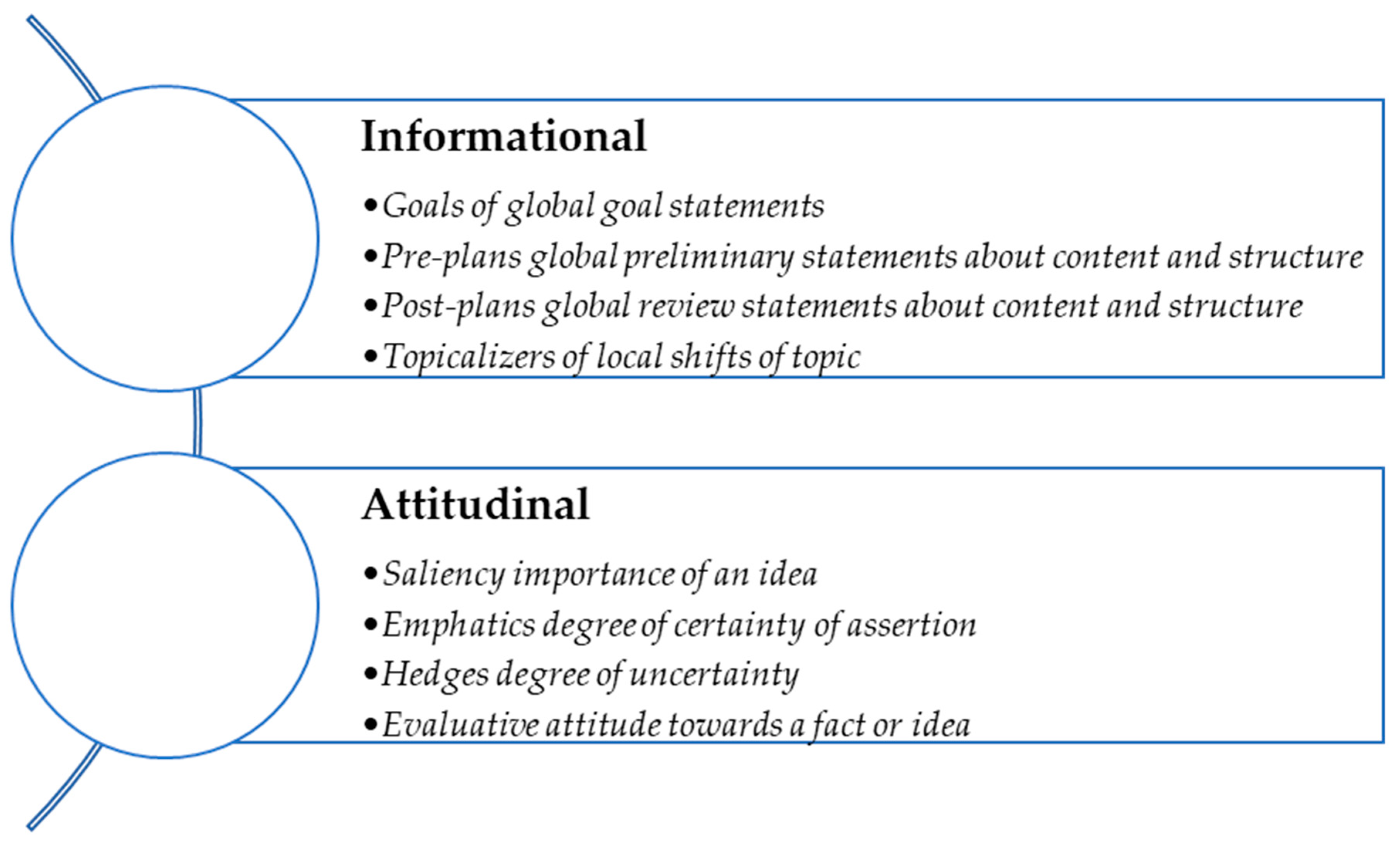

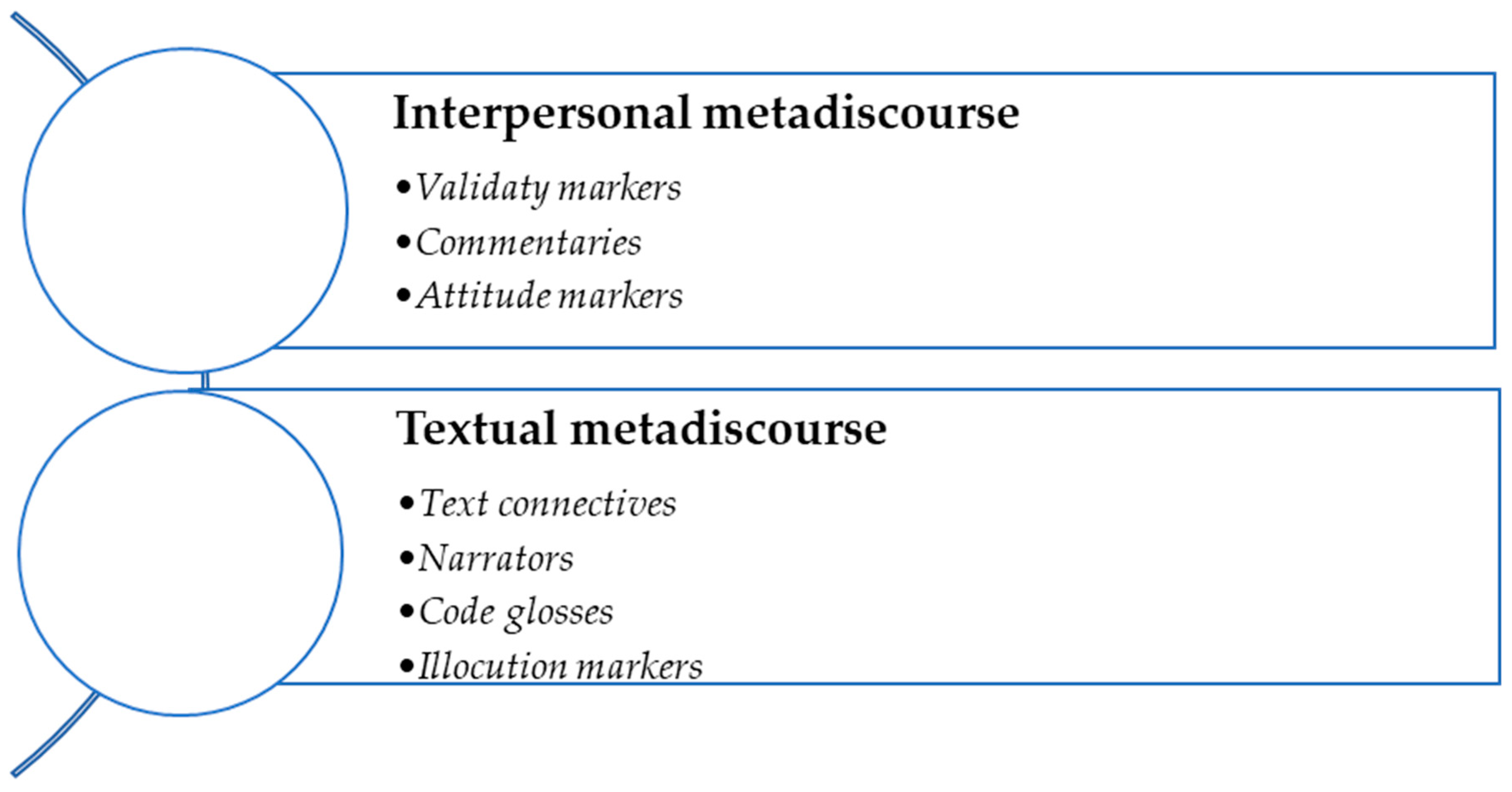

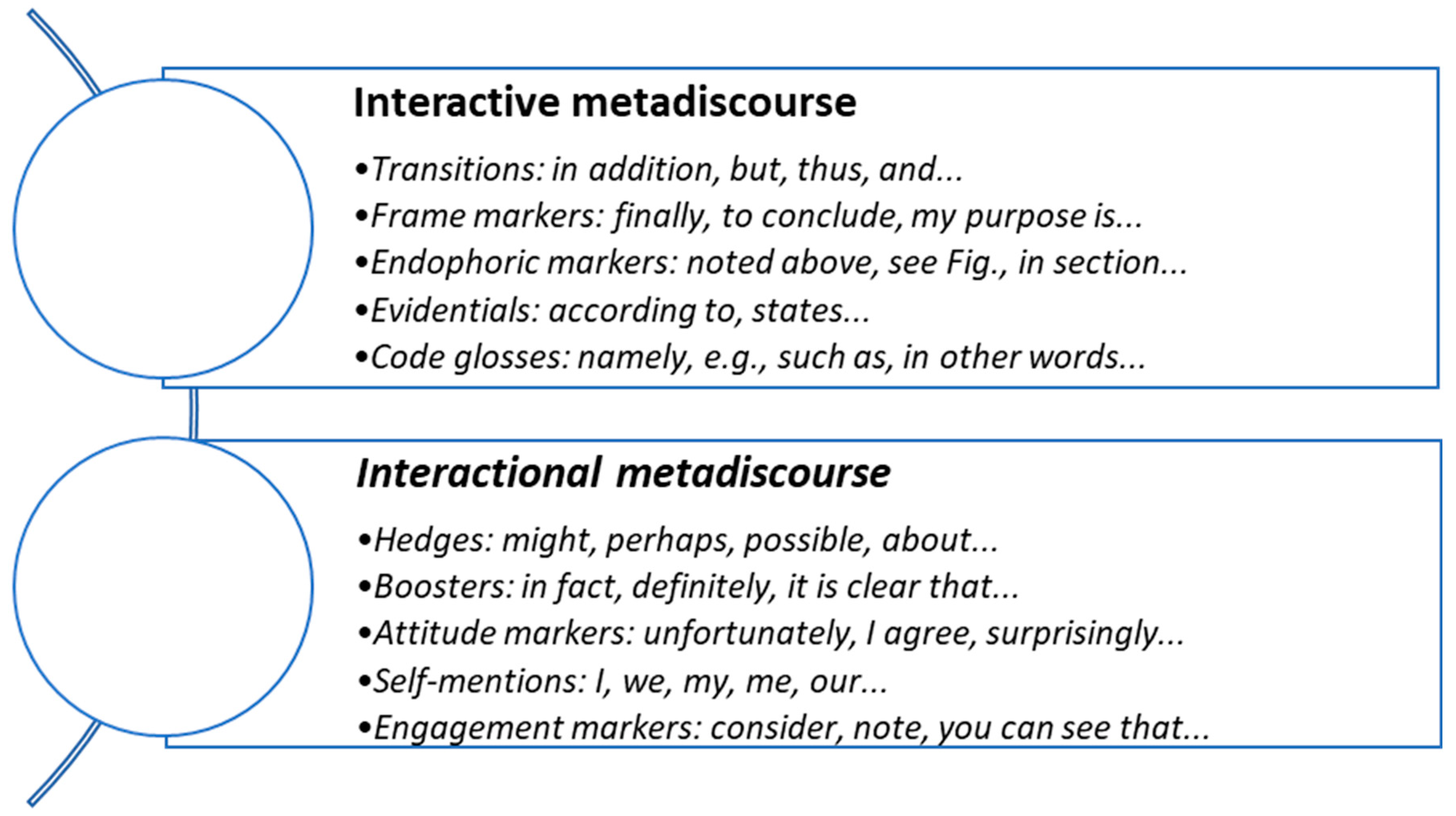

1.1. Definitions

1.2. Models

1.3. Research Objective and Hypotheses

2. Methods

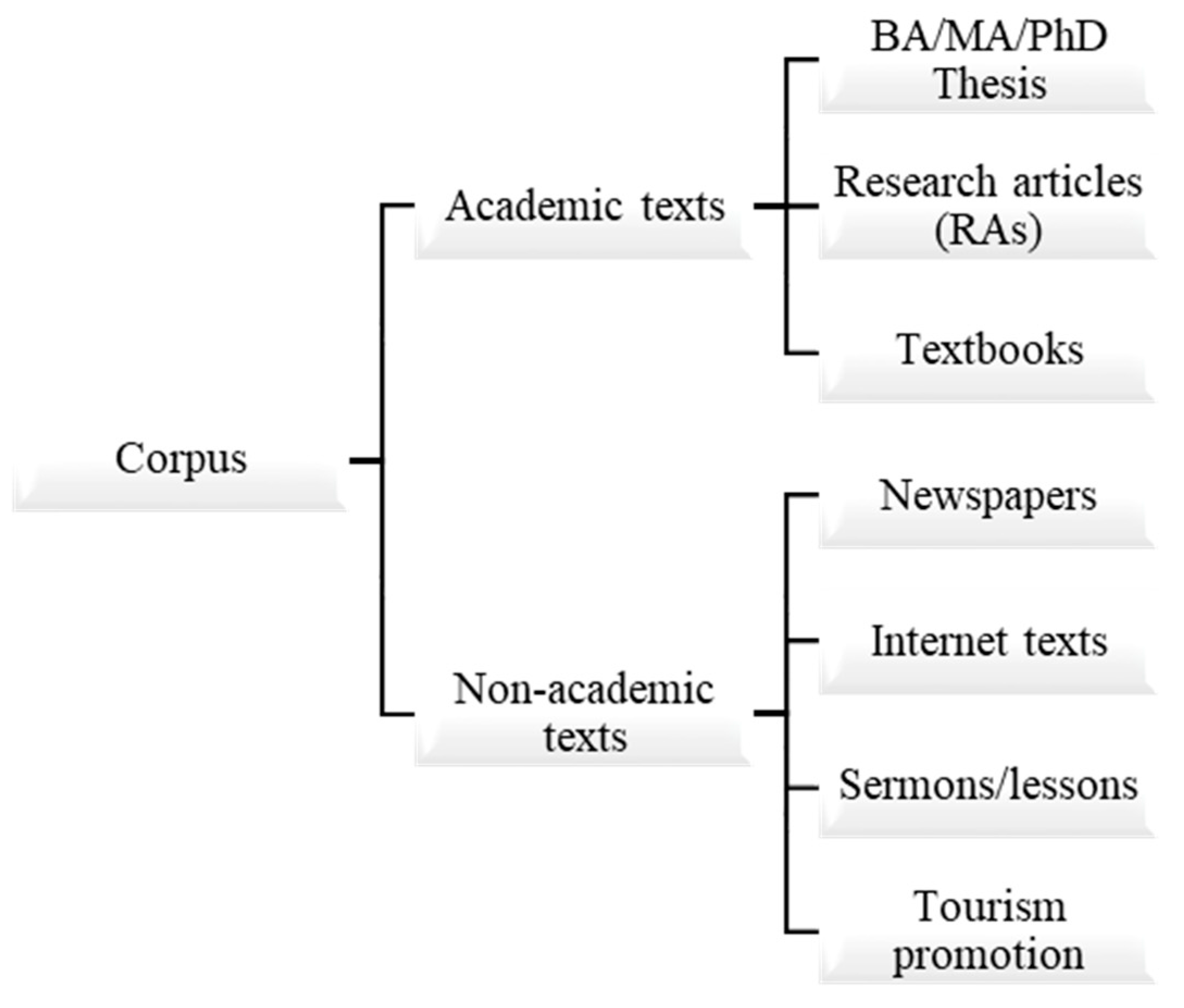

2.1. Corpus

2.2. Data Collection—Selection Criteria

- Articles that adhered to Hyland’s model were chosen because this model is the most frequently cited and most widely used in studies since the mid-2000s.

- Articles that differentiated interactive and/or interactional metadiscursive markers were chosen.

- Texts that used a classification system-based differentiation between transition, frame markers, endophoric markers, evidentials, and code gloss markers were included.

- Texts that used a classification system-based differentiation between hedges, boosters, attitude markers, self-mentions, and engagement markers were included.

- Documents that described and analysed the presence of markers in the texts were excluded when their corpus size was unknown because their data (number of appearances per 1000 words) could not be normalised prior to comparison.

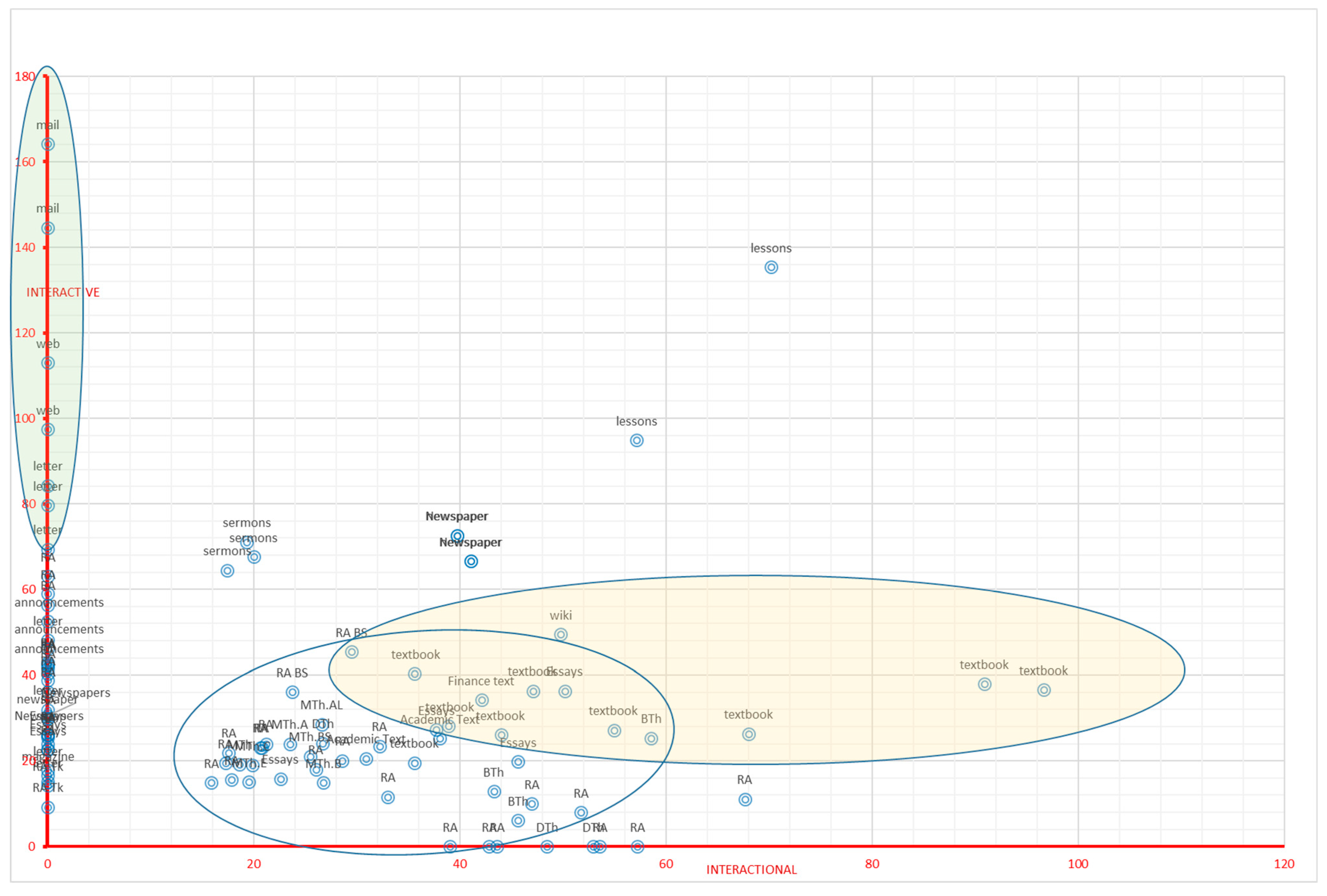

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

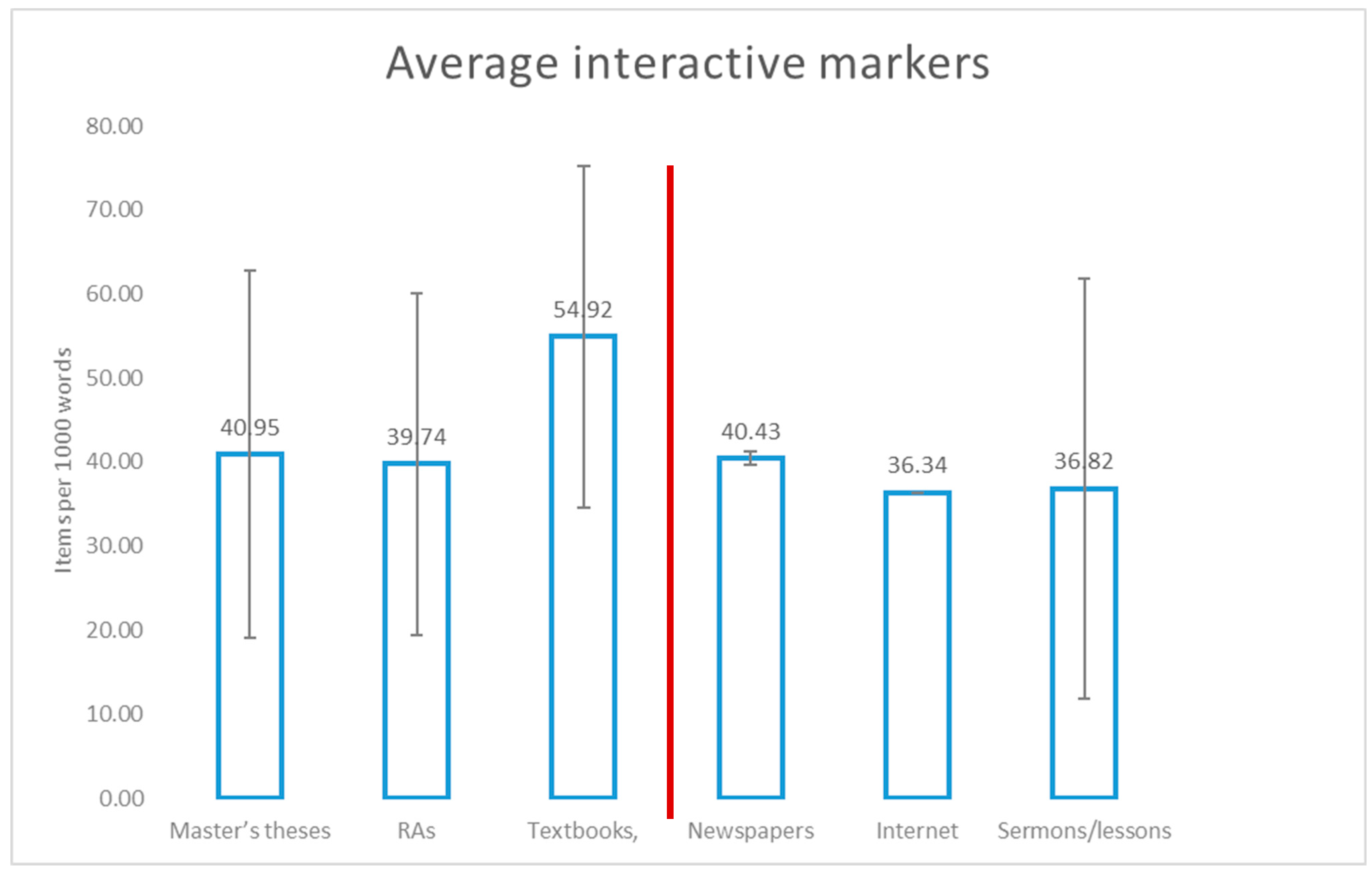

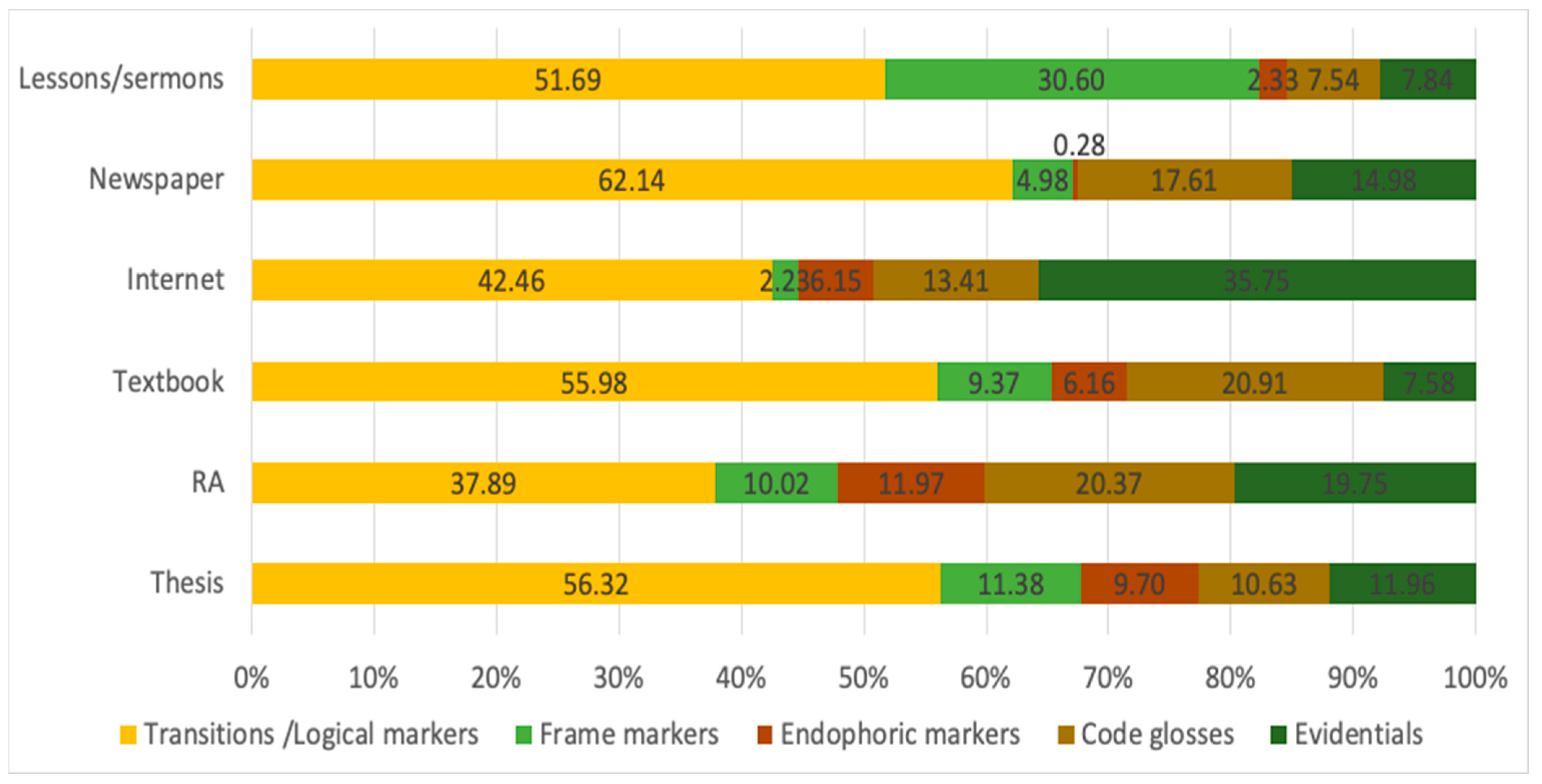

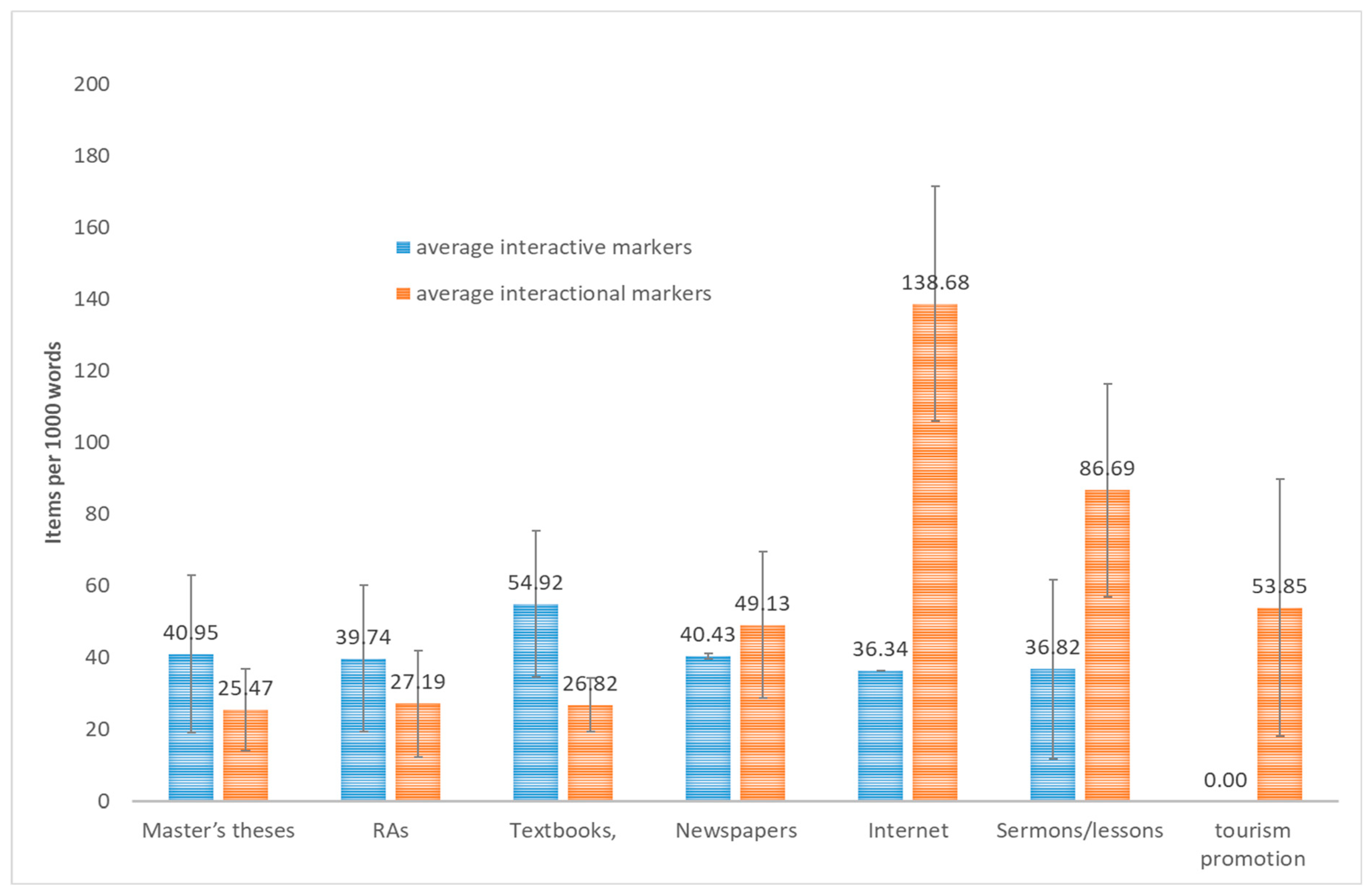

3.2. Interactive Markers

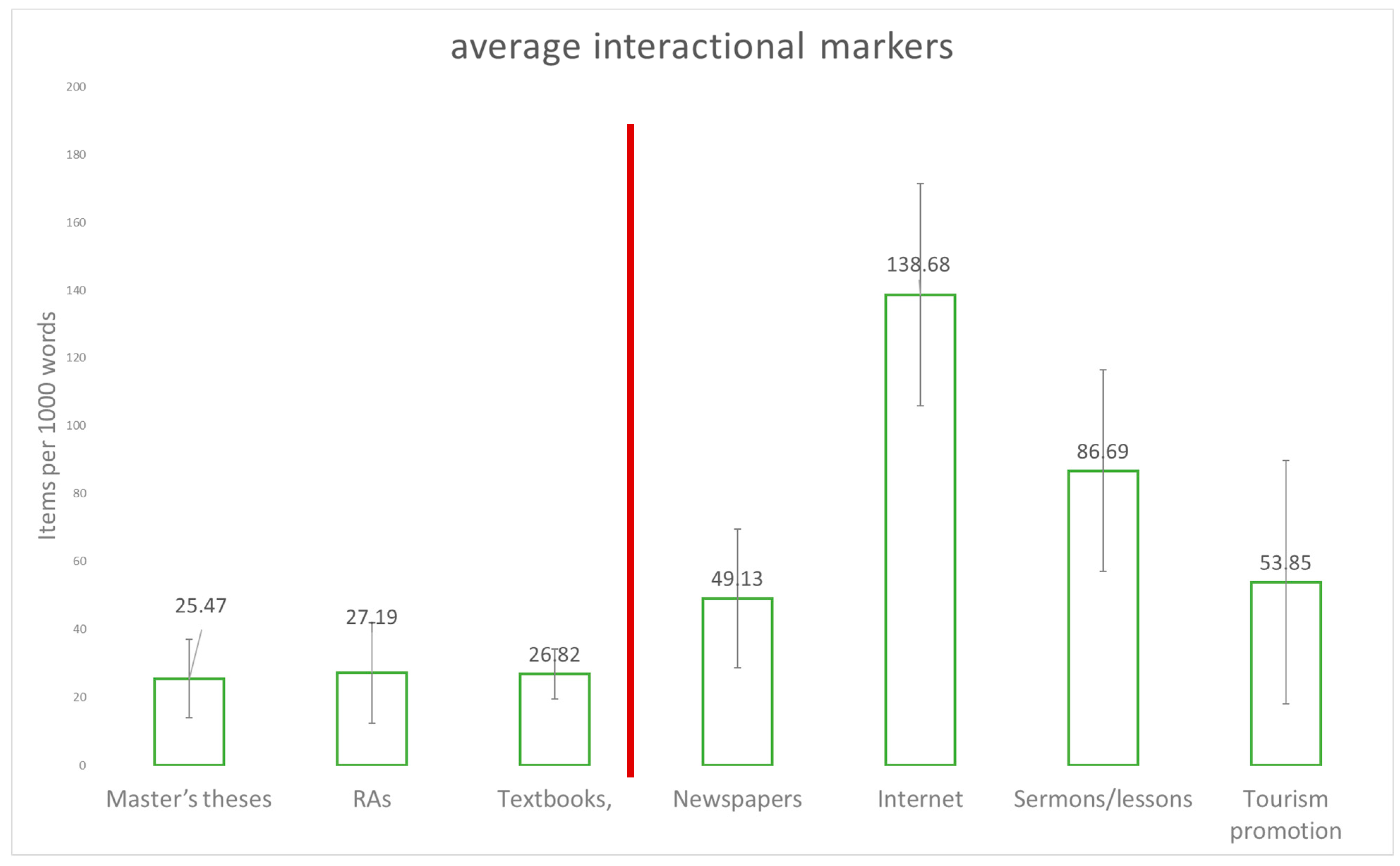

3.3. Interactional Markers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author-Reference | Year | Type of Text | Language | Corpus | |

| 1 | Abbas-Sultan [48] | 2011 | Research article | English/Arabic | 70 discussion sections of research articles: English (34) and Arabic (36); discipline: Linguistics. |

| 2 | Ahmed [49]. | 2016 | Research article | English/Pakistani | Civil engineering research articles containing two sub-corpora of British and Pakistani RAs, 45 in each |

| 3 | Akbarpour [50] | 2014 | Research article | English | 70 research articles from economics, humanities, life sciences, social sciences, law, mathematics and physical sciences, and medicine |

| 4 | Alibabaee, [51] | 2016 | Textbook | English | Six textbooks from three disciplines; for each discipline, two textbooks were selected: Mechanical engineering, medicine, and psychology |

| 5 | Alshahrani [52] | 2015 | Doctoral dissertation | English | 80 discussion and conclusion chapters from linguistics doctoral dissertations written in English by Arab and Native English graduate students |

| 6 | Alyousef and Picard [32] | 2011 | Wiki | English | Four wiki discussion pages and a report |

| 7 | Alyousef [33] | 2015 | Written assignment | English | The corpus consisted of three group assignments written in English by a total of 10 students on a finance course |

| 8 | Cao and Hu [34] | 2014 | Research article | English | 120 RAs from the subfields of language learning and teaching in applied linguistics, education, and psychology |

| 9 | Fu [35] | 2012 | Announcement | English | 220 JPs: Jobs column of the English language newspapers the Daily Telegraph and the Guardian and three websites |

| 10 | Fu-Hyland [36] | 2014 | Newspaper/magazine | English | Two journalistic genres: 200 articles from the magazines of the popular science corpus (Scientific American, New Scientist, and Science Magazine) 200 articles of opinion texts (the Guardian, the Daily Telegraph, the Los Angeles Times, and the New York Times) |

| 11 | Gallego-Hernández [37] | 2012 | Letter | French/Spanish | 19 letters from presidents of five international societies; French/Spanish versions |

| 12 | Ghadyani [38] | 2015 | Research article | English | 90 methods sections of English medical research articles in English; three study groups consisted of 30 articles selected from ISI Native journals, ISI Iranian journals, and non-ISI Iranian journals. |

| 13 | Gholam [39] | 2011 | Research article | English/Persian | 10 research articles: English (5) and Persian (5); discipline: Computer engineering |

| 14 | Hyland [17] | 1999 | Research article | English | 21 introductory coursebooks in academic disciplines: Microbiology, marketing, and applied linguistics; 21 research articles in academic disciplines: Microbiology, marketing, and applied linguistics |

| 15 | Hyland and Tse [18] | 2004 | Master’s/doctoral thesis | English | 240: 20 masters and 20 doctoral dissertations each from six academic disciplines: Applied linguistics, public administration, business studies, computer science, electrical engineering, and biology |

| 16 | Hyland [40] | 2005 | Research article | English | 240 RAs in eight academic disciplines: Philosophy (30), marketing (30), sociology (30), applied linguistics (30), philology (30), electrical engineering (30), mechanical engineering (30), and biology (30) |

| 17 | Ivorra [41] | 2014 | Web | English/Spanish | 100 business websites (50 from Spain and 50 from the US) of toy companies |

| 18 | Jensen [42] | 2009 | English | 46 e-mails from two persons in different professional roles | |

| 19 | Jin and Shang [53] | 2016 | Bachelor’s thesis | English | English abstracts of BA theses across three different disciplines (applied linguistics, material science, and electrical engineering) |

| 20 | Kan [54] | 2016 | Research article | Turkish | 20 articles from the Mustafa Kemal University Journal of Social Sciences Institute: 10 Turkish language education and 10 Turkish literature |

| 21 | Khedri and Ebrahimi [55] | 2013 | Research article | English | Results and discussion sections of 16 RAs; disciplines: English language teaching (4), civil engineering (4), biology (4), and economics (4); |

| 22 | Khedri and Heng [56] | 2013 | Research article | English | 60 RA abstracts; discipline: Applied linguistics (30) and economics (30) |

| 23 | Kuhi and Behnam [57] | 2011 | Research article/textbook | English | (20 research articles, 20 handbook chapters, 20 scholarly textbook chapters, and 20 introductory textbook chapters) in applied linguistics |

| 24 | Kuhi and Mojood [58] | 2014 | Newspaper | English/Persian | 60 newspaper editorials (written in English and Persian) from 10 elite newspapers in the US and Iran |

| 25 | Lee and Casal [59] | 2014 | Master’s thesis | English/Spanish | 200 Master’s thesis results and discussion chapters: 100 written by L1 English students and 100 written by L1 Spanish students |

| 26 | Lee and Deakin [60] | 2016 | Essay | English | 75 argumentative essays written by US-based Chinese ESL and advanced L1 English university students, organised into three comparable corpora: 25 successful (A-graded) papers, 25 less-successful ESL (B-graded) papers, and 25 successful L1 English (A-graded) argumentative essays |

| 27 | Lee and Subtirelu [61] | 2014 | Lesson | English | 36 classroom lessons organised into two comparable corpora: 18 EAP lessons from the L2CD corpus and 18 university lectures from the MICASE corpus |

| 28 | Li and Wharton [62] | 2012 | Essay | English | L1 Mandarin undergraduates’ writing; disciplines: Literary criticism and translation studies |

| 29 | Malmstrom [63] | 2016 | Sermon | English | 150 sermon manuscripts from the Church of England, the Baptist Church, and the Roman Catholic Church |

| 30 | Martin-Laguna [64] | 2015 | Essay | English/Spanish/Catalan | Three opinion essays, one in English, one in Catalan, and one in Spanish, about three topics related to the school (22 students) |

| 31 | McGrath [65] | 2012 | Research article | English | Pure mathematics research articles (25) |

| 32 | Mu and Zhang [66] | 2015 | Research article | English/Chinese | 20 journal articles in English and another 20 in Chinese; discipline: Applied linguistics |

| 33 | Mur-Dueñas [19] | 2011 | Research article | English/Spanish | 24 research articles: 12 written in English published in international journals, and 12 written in Spanish published in national journals |

| 34 | Rubio [67] | 2011 | Research article | English | Eight multi-authored articles; discipline: Agricultural sciences |

| 35 | Salar and Ghonsooly [68] | 2016 | Research article | English/Persian | 20 RAs from the knowledge management discipline: 10 Persian and 10 English |

| 36 | Sorahi and Shabani [69] | 2016 | Research article | English/Persian | 40 introductions of linguistics research articles: 20 Persian and 20 English |

| 37 | Suau-Jiménez and Dolón Herrero [70] | 2007 | Promotion of touristic services | English/Spanish | |

| 38 | Suau-Jimenez and Labata Postigo [71] | 2017 | Touristic guide | Spanish/German | Three different sub-corpora: Texts in German as the original language, texts in Spanish as the original language, and texts in German as the translated language |

| 39 | Sultan [48] | 2011 | Research article | English/Arabic | 70 discussion sections of linguistics research articles written by native speakers of English and Arabic |

| 40 | Tajeddin and Alemi [72] | 2012 | Online forum | English | 168 comments made by 28 university students of engineering via an educational forum |

| 41 | Taki and Jafarpour [73] | 2012 | Research article | English/Persian | 120 English and Persian research articles in the two disciplines of chemistry and sociology |

| 42 | Tavanpour [74] | 2016 | Newspaper | English | Sports news in newspapers (Iran Daily, Tehran Times, Kayhan International, the New York Times, and the Washington Post) |

| 43 | Yavari and Kashani [75] | 2013 | Research article | English | 32 applied linguistics research articles (introduction, method, results, and discussion/conclusion sections) |

| 44 | Yazdani and Sharifi [76] | 2014 | Research article | English/Persian | 30 English and Persian news reports (15 from each) |

References

- Halliday, M.A.K. Explorations in the Functions of Language; Arnold, E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Mauranen, A. But Here’s a Flawed Argument: Socialisation into and through Metadiscourse. In Corpus Analysis: Language Structure and Language Use; Leistyna, P., Meyer, C.F., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Neatherlands, 2003; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen-Freeman, D.; Cameron, L. Complex Systems and Applied Linguistics; Linguistics, O.A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin, D.; Tannen, D.; Hamilton, H. Introduction. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing; Discourse, C., Ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dafouz-Milne, E. The Pragmatic Role of Textual and Interpersonal Metadiscourse Markers in the Construction and Attainment of Persuasion: A Cross-Linguistic Study of Newspaper Discourse. J. Pragmat. 2008, 40, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ädel, A. Metadiscourse in L1 and L2 English; John Benjamins Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K. Metadiscourse: What is it and where is it going? J. Pragmat. 2017, 113, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande Kopple, W.J. Some exploratory discourse on metadiscourse. Coll. Compos. Commun. 1985, 36, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crismore, A. Metadiscourse: What It Is and How It Is Used in School and Non-School Social Science Texts; University of Illinois Library: Champaign, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, T.; Gong, Z. Studies on Metadiscourse since the 3rd Millennium. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ädel, A.; Mauranen, A. Metadiscourse: Diverse and divided perspectives. Nord. J. Engl. Stud. 2010, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suau Jimenez, F. La Persuasion a Traves del Metadiscurso Interpersonal en el Genero Pagina Web Institucional de Promoción Turistica en Inglés y Español. In La Lengua del Turismo: Géneros Discursivos y Terminología; Calvi, M.V., Mapelli, G., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Crismore, A.; Farnsworth, R. Metadiscourse in Popular and Professional Science Discourse. In The Writing Scholar: Studies in the Language and Conventions of Academic Discourse; Nash, W., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Crismore, A.; Markkanen, R.; Steffensen, M.S. Metadiscourse in persuasive writing—A study of texts written by american and finnish university-students. Writ. Commun. 1993, 10, 39–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Disciplinary Discourses: Social Interactions in Academic Writing; Longman: London, UK, 2000; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K. Talking to Students: Metadiscourse in Introductory Coursebooks. Engl. Specif. Purp. 1999, 18, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K.; Tse, P. Metadiscourse in academic writing: A reappraisal. Appl. Linguist. 2004, 25, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Dueñas, P. An intercultural analysis of metadiscourse features in research articles written in English and in Spanish. J. Pragmat. 2011, 43, 3068–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suau-Jimenez, F. Quality translation of hotel websites: Interpersonal discourse and customer’s engagement. Onomazein 2015, 32, 152–170. [Google Scholar]

- Míguez-Álvarez, C.; Gonzalez-Varela, L.; Cuevas-Alonso, M. Identification of Metadiscourse Markers in Bachelor’s Degree Theses in Spanish: Introduction of a Text Mining Tool. Span. J. Appl. Linguist. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Míguez-Álvarez, C.; Cuevas-Alonso, M.; Saavedra, A. The relationship between phonological awareness and reading in Spanish: A meta-analysis. Lang. Learn. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Disciplinary interactions: Metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 2004, 13, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Metadiscourse: Mapping Interactions in Academic Writing. Nord. J. Engl. Stud. 2010, 9, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, E. Poring over the findings: Interpersonal authorial engagement in applied linguistics papers. J. Pragmat. 2011, 43, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, T. Textual metadiscourse in research articles: A marker of national culture or of academic discipline? J. Pragmat. 2004, 36, 1807–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilifar, A.; Alavi-Nia, M. We are surprised; wasn’t Iran disgraced there? A functional analysis of hedges and boosters in televised Iranian and American presidential debates. Discourse Commun. 2012, 6, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorian, M.; Biria, R. Interpersonal metadiscourse in persuasive journalism: A study of texts by American and Iranian EFL columnists. J. Mod. Lang. 2010, 20, 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, G.R.; Mansoori, S. A Contrastive Study on Metadiscourse Elements Used in Humanities vs. Non Humanities across Persian and English. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2011, 4, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, G. Four perspectives on L2 pragmatic development. Appl. Linguist. 2001, 22, 502–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.; McCarthy, M. Cambridge Grammar of English a Comprehensive Guide: Spoken and Written English Grammar and Usage; University of Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alyousef, H.S.; Picard, M.Y. Cooperative or collaborative literacy practices: Mapping metadiscourse in a business students’ wiki group project. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 27, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, H.S. An Investigation of Metadiscourse Features in International Postgraduate Business Students’ Texts: The Use of Interactive and Interactional Markers in Tertiary Multimodal Finance Texts; Sage Open: Newberry Park, CA, USA, 2015; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, F.; Hu, G.W. Interactive metadiscourse in research articles: A comparative study of paradigmatic and disciplinary influences. J. Pragmat. 2014, 66, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.L. The use of interactional metadiscourse in job postings. Discourse Stud. 2012, 14, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Hyland, K. Interaction in two journalistic genres: A study of interactional metadiscourse. Engl. Text Constr. 2014, 7, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Hernández, D. Metadiscurso y traducción en el lenguaje de los negocios: Estudio basado en corpus (francés-español). Rev. Electrónica Lingüistica Apl. 2012, 11, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadyani, F.; Tahririan, M.H. Interactive Markers in Medical Research Articles Written by Iranian and Native Authors of ISI and Non-ISI Medical Journals: A Contrastive Metadiscourse Analysis of Method Section. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2015, 5, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholam, R.; Zarei, G.; Mansoori, S. Metadiscursive Distinction between Persian and English: An Analysis of Computer Engineering Research Articles. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2011, 2, 1037. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K. Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Stud. 2005, 7, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.M.I. Cultural Values and their Correlation with Interactional Metadiscourse Strategies in Spanish and us Business Websites. Atlantis-J. Span. Assoc. Anglo-Am. Stud. 2014, 36, 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, A. Discourse strategies in professional e-mail negotiation: A case study. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2009, 28, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabbazi-Oskouei, L. Orality in Persian Argumentative Discourse: A Case Study of Editorials. Iran. Stud. 2016, 49, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, E. Active participation within written argumentation: Metadiscourse and editorialist’s authority. J. Pragmat. 2004, 36, 687–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukma, B.P.; Sujatna, E.T.S. Interpersonal metadiscourse markers in opinion articles: A study of texts written by indonesian writers. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 2014, 3, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Llopis, M.A.O. Krugman vs Garicano: Individual and Cultural Differences in the Rhetoric of Two Economic Op-Ed Writers; Hermes: Aarhus, Denmark, 2016; pp. 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, D. Literacy: An Introduction to the Ecology of Written Language; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, A. A contrastive study of metadiscourse in english and arabic linguistics research articles. Acta Linguist. 2011, 5, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Memon, S.; Soomro, A.F. An Investigation of the Use of Interactional Metadiscourse Markers: A Cross-Cultural Study of British and Pakistani Engineering Research Articles. Int. Res. J. Lang. Lit. 2016, 27, 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Akbarpour, M.; Sadeghoghli, H. The Study on Ken Hyland’s Interactional Model in OUP Publications. Int. J. Lang. Linguist. 2015, 3, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alibabaee, A.; Eslamizadeh, F.; Soleimani, F. A Contrastive Study of ESP Text Books and Content Books for Metadiscourse Markers: The Cases of Psychology, Medicine, and Mechanical Engineering. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2016, 6, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A. A Cross-linguistic Analysis of Interactive Metadiscourse Devices Employment in Native English and Arab ESL Academic Writings. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2015, 5, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Shang, Y. Analyzing Metadiscourse in the English Abstracts of BA Theses. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2016, 7, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, M.O. The Use of Interactional Metadiscourse: A Comparison of Articles on Turkish Education and Literature. Educ. Sci. -Theory Pract. 2016, 16, 1639–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Khedri, M.; Ebrahimi, S.J.; Heng, C.S. Patterning of interactive Metadiscourse markers in result and discussion sections of academic research articles across disciplines. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2013, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Khedri, M.; Ebrahimi, S.J.; Heng, C.S. Interactional metadiscourse markers in academic research article result and discussion sections. 3L: Lang. Linguist. Lit. 2013, 19, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhi, D.; Behnam, B. Generic Variations and Metadiscourse Use in the Writing of Applied Linguists: A Comparative Study and Preliminary Framework. Writ. Commun. 2011, 28, 97–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhi, D.; Mojood, M. Metadiscourse in Newspaper Genre: A Cross-linguistic Study of English and Persian Editorials. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 98, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Casal, J.E. Metadiscourse in results and discussion chapters: A cross-linguistic analysis of English and Spanish thesis writers in engineering. System 2014, 46, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Deakin, L. Interactions in L1 and L2 undergraduate student writing: Interactional metadiscourse in successful and less-successful argumentative essays. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2016, 33, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Subtirelu, N.C. Metadiscourse in the classroom: A comparative analysis of EAP lessons and university lectures. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2015, 37, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wharton, S. Metadiscourse repertoire of L1 Mandarin undergraduates writing in English: A cross-contextual, cross-disciplinary study. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2012, 11, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmstrom, H. Engaging the Congregation: The Place of Metadiscourse in Contemporary Preaching. Appl. Linguist. 2016, 37, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Laguna, S.; Alcon, E. Do Learners Rely on Metadiscourse Markers? An Exploratory Study in English, Catalan and Spanish. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 173, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, L.; Kuteeva, M. Stance and engagement in pure mathematics research articles: Linking discourse features to disciplinary practices. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2012, 31, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.J.; Zhang, L.J.; Ehrich, J.; Hong, H. The use of metadiscourse for knowledge construction in Chinese and English research articles. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2015, 20, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.M.D. A pragmatic approach to the macro-structure and metadiscoursal features of research article introductions in the field of Agricultural Sciences. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2011, 30, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salar, S.; Ghonsooly, B. A comparative analysis of metadiscourse features in knowledge management research articles written in English and Persian. Int. J. Res. Stud. Lang. Learn. 2016, 5, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorahi, M.; Shabani, M. Metadiscourse in Persian and English Research Article Introductions. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2016, 6, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suau-Jiménez, F.; Dolón Herrero, R. The Importance of Metadiscourse in the Genre ‘Promotion of Touristic Services and/or Products’: Differences in English and Spanish. In Languages for Specific Purposes: Searching for Common Solutions; Gálova, D.E., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars Publishings: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Suau-Jimenez, F.; Labarta Postigo, M. El discurso interpersonal en la guía turística en español y alemán y su importancia para la traducción. Normas 2017, 71, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddin, Z.; Alemi, M. L2 Learners’ Use of Metadiscourse Markers in Online Discussion Forums. Issues Lang. Teach. 2012, 1, 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Taki, S.; Jafarpour, F. Engagement and stance in academic writing: A study of English and Persian research articles. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Farnia, M.; Tavanpour, N. Interactional Metadiscourse Markers in Sports News in Newspapers: A Cross-cultural study of American and Iranian Columnists. Philologist 2016, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yavari, M.; Kashani, A.F. Gender-based study of metadiscourse in research articles’ rhetorical sections. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 2013, 2, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, S.; Sharifi, S.; Elyassi, M. Interactional Metadiscourse in English and Persian News Articles about 9/11. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2014, 4, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuevas-Alonso, M.; Míguez-Álvarez, C. Metadiscursive Markers and Text Genre: A Metareview. Publications 2021, 9, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9040056

Cuevas-Alonso M, Míguez-Álvarez C. Metadiscursive Markers and Text Genre: A Metareview. Publications. 2021; 9(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuevas-Alonso, Miguel, and Carla Míguez-Álvarez. 2021. "Metadiscursive Markers and Text Genre: A Metareview" Publications 9, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9040056

APA StyleCuevas-Alonso, M., & Míguez-Álvarez, C. (2021). Metadiscursive Markers and Text Genre: A Metareview. Publications, 9(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9040056