Perceived Challenges to Anglophone Publication at Three Universities in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How much pressure and desire do Chilean scholars feel to publish?

- (2)

- What have been their experiences with publishing or attempting to do so?

- (3)

- What do they perceive as their biggest challenges to publishing?

- (4)

- Do their perceptions differ from those of writing center directors and other applied linguists?

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Instruments

- Scholars’ pressure and desire for publication of their research, whether in English-medium international journals (EMI), English-medium regional journals (EMR), Spanish-medium international journals (SMI), or Spanish-medium regional journals (SMR);

- Scholars’ experiences with publication or publication attempts;

- Their perceived challenges to getting published.

3.3. Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Scholars’ Desires and Experiences with Publication (Questions 1 and 2)

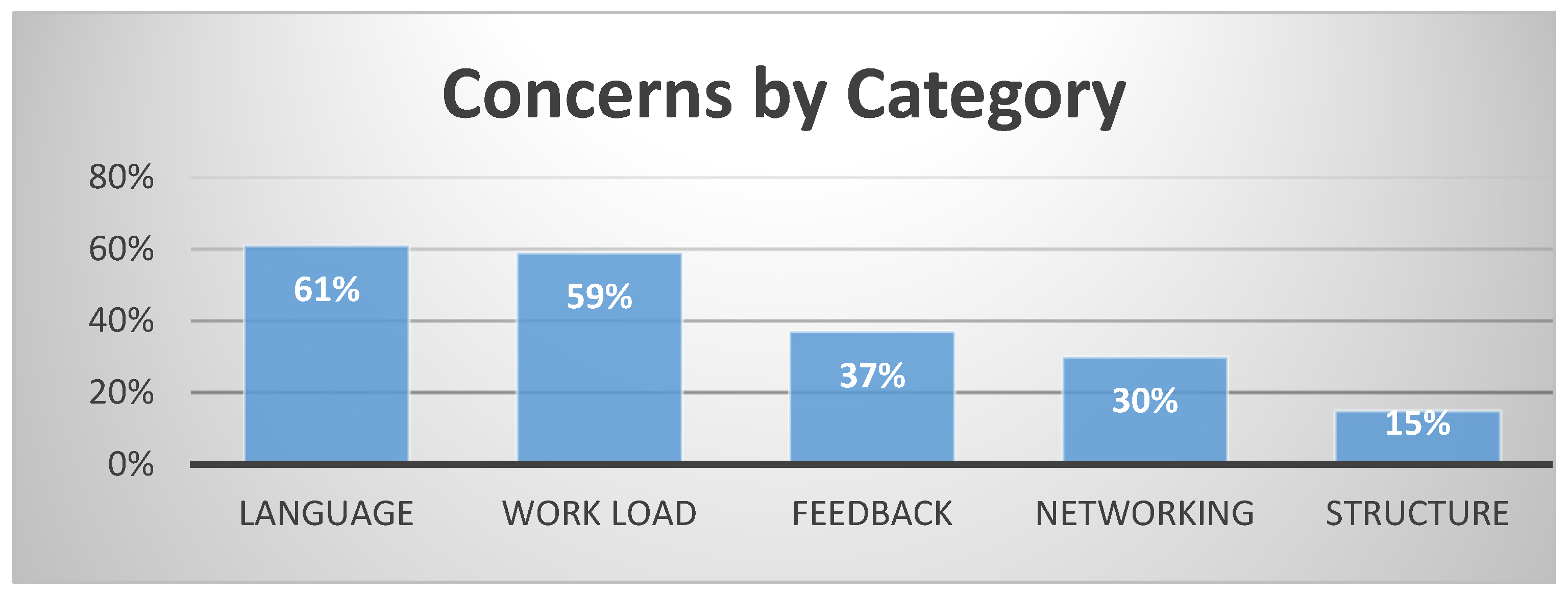

4.2. Perceived Challenges to Getting Published (Question 3)

4.2.1. Language Issues

4.2.2. Workload

4.2.3. Feedback and Networking

4.2.4. Structure

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Interview Questions about Publishing at Magallanes and Talca

- Personal information:NameNumber of years of serviceCurrent positionGraduate degrees, from where, in what subjects

- Have you published a research article (RA) in English? Yes NoIf Yes, how many? 1 2 3 4 5 or more

- Have you published a research article (RA) in Spanish? Yes NoIf Yes, how many? 1 2 3 4 5 or more

- Have you published a research article (RA) in another language? Yes NoIf Yes, how many? 1 2 3 4 5 or more

- Have you ever attempted to publish a RA? Describe the process you went through, number of rejections, reviewers’ comments, etc.

- Have you attempted or published other academic writings, such as book reviews, conference proceedings, letters to the editor, etc.? Describe that process.

- Do you want to publish in English? Spanish? Please explain and specify the following: English-medium international (EMI), English-medium regional (EMR), Spanish-medium international (SMI) or Spanish-medium regional/local (SMR). Why do you want to publish in this type (or types) of journal?

- Rank-order the following challenges for you to publish in English, placing the biggest challenge first: Then comment on your ranking.

- Problems managing heavy workload

- Problems with English language

- Problems with knowing how to structure the research article (RA)

- Problems making contacts with possible collaborators, editors, conference organizers

- Problems with getting feedback about my research and/or writing

- Other?

- Describe your workload at the university. Does it impact your academic writing?

- How could the administration help you to get published?

- Are you familiar with the English Academic Writing Center? If not, how could it be publicized? If so, have you used it? What kind of help did you receive? How could the AWC help you more?

Appendix A.2. Interview Tabulations for Magallanes and Talca

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. SurveyMonkey Questions about Publishing at Pontificia University, Santiago

- Por cuanto tiempo ha estado involucrado con trabjo académico?What is your number of years of academic service?

- A que Unidad Academica pertenece?To which academic unit do you belong?

- Cual es su nivel educacional?What is your highest level of education?

- Le interesa publicar algún articulo académico en Ingles? Espanol? Otro idioma?Are you interested in publishing in English? Spanish? Other?

- Anteriomente, ha publicado algún articulo académico en Ingles? Espanol: Otro idioma?Have you published a research article before?

- Solo si ha publicado en Ingles: Cuantos artículos?How many articles have you published in English?

- Ha intentado alguna ves publicar o ha publicado algún otro escrito académico, por ejemplo, Critica/resena de un libro? Estructura de presentación? Carta al editor? Otro?Have you attempted or published other types of academic writing?

- Si esta interesado en publicar: Le gustaria publicar en un medio?In what types of journals would you like to publish?

- Des las siguientes opciones: Cuales representan de mejor manera sus razones para publicar en ciertos tipos de revistas especializadas? Seleccione todas las opciones que correspondan.Why do you want to publish in those journals?

- En su opinión, Cual es el nivel de dificultad de las siguientes que comúnmente enfrentan los académicos chilenos para publicar en ingles, siendo 1 la mas difícil y 5 la menos difícil:administrar la carga laboral; idioma Ingles; conocimiento acerca; establecer contacto; feedbackRank order the challenges for publishing in English, with the biggest first: workload, language, structure, networking, and feedback.

- Conoce o ha escuchado acerca del English UC Writing Center?Are you familiar with the English UC Academic Writing Center?

- Ha asistido a talleres grulpales en el English Academic Writing Center?If so, have you attended workshops at the AWC?

- Ha asistido a sesiones individuales en el English Academic Writing Center? Que aspectos de la escritura trabajo (ideas, organización, creación de borrador, edición de estructura, revisión)?If so, have you attended individual sessions at the AWC? And which aspects did you work on (ideas, organization, structure, editing)?

Appendix B.2. SurveyMonkey Tabulations for Pontificia Universidad, Santiago

References

- Curry, M.J.; Lillis, T. Multilingual scholars and the imperative to publish in English: Negotiating interests, demands, and rewards. TESOL Q. 2004, 38, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowerdew, J. Discourse community, legitimate peripheral participation, and the nonnative English-speaking scholar. TESOL Q. 2000, 34, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Landa, L. Academic language barriers and language freedom. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2006, 7, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M. English writing for international publication in the age of globalization: Practices and perceptions of Mainland Chinese. Publications 2015, 3, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englander, K. Resistance, Resignation, Appropriation, Deception: Agency in the Figured World of the Scholar in the Periphery. Presented at the PRISEAL 4, Reykjavik, Iceland, 14–16 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, M.J.; Lillis, T. A Scholar’s Guide to Getting Published in English: Critical Choices and Practical Strategies; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-78309-059-4. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.C. Learning to write for publication in English through genre-based pedagogy: A case in Taiwan. System 2014, 45, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, D. The apprenticeship approach to advanced academic literacy: Graduate students and their mentors. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2007, 13, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargill, M.; Burgess, S. Introduction to the special issue: English for research publication purposes. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2008, 7, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swales, J. Genre Analysis; Cambridge UP: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 9780521338134. [Google Scholar]

- Casanave, C.P. Local interactions: Constructing contexts for composing in a graduate sociology program. In Academic Writing in a Second Language; Belcher, D., Braine, G., Eds.; Ablex: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- Flowerdew, J. Problems in writing for scholarly publication in English: The case of Hong Kong. J. Second Lang. Writ. 1999, 8, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, T.; Curry, M.J. The politics of English, language and uptake. In AILA Review 28; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowerdew, J. Attitudes of journal editors to nonnative speaker contributions. TESOL Q. 2001, 35, 121–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.W. Science journal paper writing in an EFL context: The case of Korea. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2009, 28, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Academic publishing and the myth of linguistic injustice. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 2016, 31, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D. Verbal Hygiene, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, P. Shakespeare and the English poets: The influence of native speaking English reviewers on the acceptance of journal articles. Publications 2019, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, T.; Curry, M.J. Professional academic writing by multilingual scholars: Interactions with literacy brokers in the production of English-medium texts. Writ. Commun. 2006, 23, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.; Pérez-Llantada, C.; Plo, A.R. English as an international language of scientific publication: A study of attitudes. World Engl. 2011, 30, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, L. The institutional context of ‘linguistic injustice’: Norwegian social scientists and situated multilingualism. Publications 2019, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, T.; Curry, M.J. Academic Writing in a Global Context: The Politics and Practices of Publishing in English; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780415468831. [Google Scholar]

- Lillis, T.; Curry, M.J. Reframing notions of competence in scholarly writing: From individual to networked activity. Revista Canaria de Estudio Ingleses 2006, 53, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Apprentice scholarly writing in a community of practice: An intraview of an NNES graduate student writing a research article. TESOL Q. 2007, 41, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Flowerdew, J. Shaping Chinese novice scientists’ manuscripts for publication. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2007, 16, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, M.J. Dr. Mary Jane Curry on Multilingual Scholars; RIA #152. Interview; Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hultgren, A.K. English as the language for academic publication: On equity, disadvantage, and ‘non-nativeness’ as a red herring. Publications 2019, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagarajah, A.S. Geopolitics of Academic Writing; Pittsburgh UP: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780822972389. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S. Cultural thought patterns in inter-cultural education. Lang. Learn. 1966, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, U. Contrastive Rhetoric: Cross-Cultural Aspects of Second Language Writing; Cambridge UP: Cambridge, UK, 1996; ISBN 0-521-44688-0. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, J.; Feak, C. Academic Writing for Graduate Students, 3rd ed.; Michigan UP: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2012; ISBN 0472088564. [Google Scholar]

- Morell, P.; Cesteros, S.P. Genre pedagogy and bilingual graduate students’ academic writing. Publications 2019, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, M.J. (School of Education, University of Rochester, New York, NY, USA). Personal communication, February 2017.

- Perez-Llantada, C. Genres in the forefront, languages in the background: The scope of genre analysis in language-related scenarios. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2015, 19, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solli, K.; Odemark, I.L. Multilingual research writing beyond English: The case of Norwegian academic discourse in an era of multilingual publication practices. Publications 2019, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.W. Challenges of entering discourse communities through publishing in English: Perspectives of nonnative-speaking doctoral students in the United States of America. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2004, 3, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, M.J.; Lillis, T. Academic research networks: Accessing resources for English-medium publishing. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2010, 29, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Negotiating knowledge contribution to multiple discourse communities: A doctoral student of computer science writing for publication. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2006, 15, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K. Epistemicide: The tale of a predatory discourse. Translator 2007, 13, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- For Authors. Nature. Available online: https://www.nature.com/nature/for-authors/ (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- Horner, B.; Trimbur, J. English only and US college composition. Coll. Compos. Commun. 2002, 53, 594–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Molina-Natera, V. (Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Cali-Columbia, Bogota, Columbia). Personal communication, 24 February 2017.

- Mweru, M. Why Kenyan academics do not publish in international refereed journals. In World Social Science Report: Knowledge Divides; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 110–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lunsford, A.; Ede, L. Writing Together: Collaboration in Theory and Practice; Bedford/St. Martin’s: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MDPI Author Service. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/authors/english (accessed on 28 November 2018).

- Fazel, I. Writing for journal publication: An overview of NNES challenges and strategies. Pan Pac. Assoc. Appl. Linguist. 2013, 17, 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, R.M. World Englishes. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2001, 30, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Gao, Y. Dual publication and academic inequality. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 1997, 17, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, M.J. Strategies and tactics in academic knowledge production by multilingual scholars. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2014, 22, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, J.; Feak, C. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts; Michigan UP: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009; ISBN 0472033352. [Google Scholar]

- Gosden, H. Verbal reports of Japanese novices’ research writing practices in English. J. Second Lang. Writ. 1996, 5, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosden, H. Research writing and NNSs: From the editors. J. Second Lang. Writ. 1992, 1, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | |||

| Institution | # Students | Prestige | Academic Units |

| UM (Punta Arenas) N = 26 | 3000 | Ranked 33 out of 60 in Chile | Biology |

| Education | |||

| Hard Sciences | |||

| Law | |||

| TA (Talca) N = 5 | 11,000 | Ranked 16 out of 60 in Chile | Health |

| Agriculture | |||

| Business/Economics | |||

| Law | |||

| PUC (Santiago) N = 160 | 30,000 | Ranked 2 out of 60 in Chile | Medicine |

| Engineering Sciences | |||

| Humanities | |||

| (b) | |||

| Institution | Faculty | Education | Years of Service |

| UM (Punta Arenas) N = 26 | 200 | Ph.D.: 16 61% | >20 yrs: 3 |

| ~15 yrs: 4 | |||

| ~10 yrs: 2 | |||

| TA (Talca) N = 5 | 500 | Ph.D.: 4 80% | >20 yrs: 1 |

| ~15 yrs: 3 | |||

| ~10 yrs: 4 | |||

| PUC (Santiago) N = 160 | 3500 | Ph.D. or post-doc: 106 (67%) | >20 yrs: 85 |

| ~15 yrs: 42 | |||

| ~10 yrs: 33 | |||

| Institution | Desire for English | Desire for Spanish | Published in English | Published in Spanish, Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM and TA N = 31 | 24 (75%) | 3 (10%) | >5: 10 (33%) | >5: 10 (33%) |

| 3–4: 6 | 3–4: 2 | |||

| 1–2: 8 | 1–2: 9 | |||

| 0: 7 | 0: 11 | |||

| Total pub: 24 (77%) | Total: 21 (67%) | |||

| PUC N = 160 | 159 (99%) | 114 (71%) | >5: 66 (41%) | [Breakdown N/A] |

| 3–4: 21 (13%) | 65 (75%) | |||

| 1–2: 37 (23%) | Other langs:16 (10%) | |||

| 0: 36 (23%) | ||||

| Total pub:124 (78%) | Total pub:125 (78%) |

| Institution | Language | Workload | Feedback | Networking | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM and TA Total N = 31 | 20 (64%) | 22 (88%) | 6 (22%) | 11 (37%) | 4 (16%) |

| Response | Response | Response | Response | Response | |

| N = 31 | N = 25 | N = 30 | N = 30 | N = 25 | |

| PUC Total N = 160 | 74 (59%) | 72 (59%) | 58 (39%) | 39 (29%) | 19 (15%) |

| Response | Response | Response | Response | Response | |

| N = 126 | N = 122 | N = 148 | N = 135 | N = 126 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Broekhoff, M. Perceived Challenges to Anglophone Publication at Three Universities in Chile. Publications 2019, 7, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications7040061

Broekhoff M. Perceived Challenges to Anglophone Publication at Three Universities in Chile. Publications. 2019; 7(4):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications7040061

Chicago/Turabian StyleBroekhoff, Marna. 2019. "Perceived Challenges to Anglophone Publication at Three Universities in Chile" Publications 7, no. 4: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications7040061

APA StyleBroekhoff, M. (2019). Perceived Challenges to Anglophone Publication at Three Universities in Chile. Publications, 7(4), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications7040061