The UK Scholarly Communication Licence: Attempting to Cut through the Gordian Knot of the Complexities of Funder Mandates, Publisher Embargoes and Researcher Caution in Achieving Open Access

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rise of Open Access and Mandates

2.2. Copyright and Culture

2.3. The Role of Libraries

2.4. Possible Solutions—Policy and Practice

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Why Is the Licence Needed?

The desire to work towards a different kind of system, particularly involving greater openness, was seen as important by all the participants. Many participants listed the UK-SCL as one of a number of OA-related initiatives in which they were involved, which included activities varying from setting up OA university presses to participation in wider initiatives such as Knowledge Unlatched. These initiatives were in general, like the UK-SCL in particular, seen as being aimed at producing a more sustainable OA environment. In this context, national initiatives, such as policy mandates were viewed as positive drivers, but there was still recognised to be considerable inertia in the system.“UK tax money funds research which then is created in the institution, is written up by academics within the institution, is refereed by academics in the universities, is then given away for free to a commercial third party with shareholders, who then charges us to buy it back. I mean who in their right mind would invent that as a model of disseminating research?”RG-EA

Participants felt that these practices were embedded within the scholarly culture, and to move forward in transitioning to and promoting openness, they would need to be addressed:“… their priority is to get published, especially with certain publishers, and then therefore they will tend to do what is necessary in order for that to happen, without necessarily scrutinising the copyright statement”.Pre-92-EA

“There’s hundreds of years’ worth of precedence with this. So we want to move to a world where openness is rewarded and we move away from, sort of perceived journal prestige all the time and impact factors.”RG-EA

This gap between policy and practice was seen as being reinforced by the complex and emotive nature of copyright and IPR, making it hard to advocate alternative approaches:“We’ve had the current [policy] in place for a number of years…but we do not enforce the terms and conditions at all and that could be a problem, because we’ve acquiesced. We’ve allowed this situation through custom and practice to develop over a course of years.”RG-LA

Therefore, a lack of clarity, coupled with the complexity and academics’ sense of personal ownership in the work they have produced, all contribute to difficulties balancing the different needs of the different actors (researchers, their institutions, funders, publishers, etc.).“… when you start talking about these issues, the complexity of it overlaid with the fact that people have that investment in it and feel like they don’t want to lose out.”Pre-92-LA

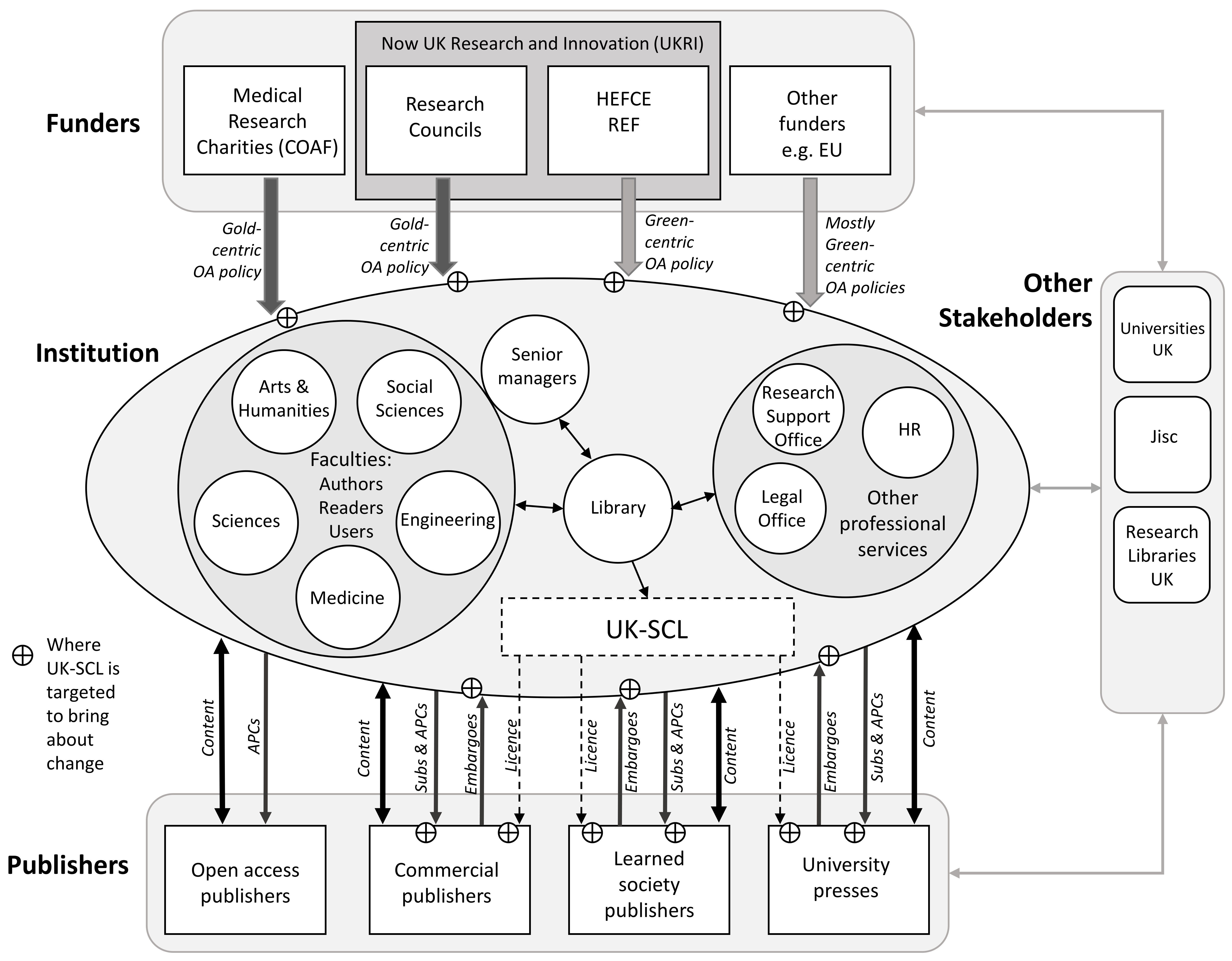

The build-up of these policies was seen as an instrumental factor of the complexity termed as the, “the policy stack” by some participants. This was seen as particularly complicated by the collaborative nature of research and overlain by complexity associated with publisher policies:“It’s not uncommon to have more than one funder per project…there will normally be at least two open access policies that apply; your funders, and HEFCE’s because that applies potentially to everything … They are sort of similar, in that they all want open access but they define this in slightly different ways.”H-U

The context then was seen to be one where there was a desire to create fundamental change in the scholarly communication system leading to greater openness, but where doing so was fraught with complexity. All of this overlay a culture within most academic disciplines where esteem was linked very clearly to publication in particular respected journals and where copyright was a sensitive issue on which the intervention of the institution was often not welcomed. Support services that serve researchers in institutions often found themselves undertaking tortuous processes in order to reconcile the differing demands of the involved stakeholders, which consequently had an impact on the overall engagement with open access by authors.“A lot of work is done collaboratively, cross-institutional, cross-national, sometimes with multiple funders, so you start getting a swirl of policies involved there. You’ve then got publishers who also have different policies and some publisher policies are different depending on where you got funded from.”RG-EA

Mandates were therefore seen as having the positive effect of encouraging OA but had created operational challenges for institutions and some amount of confusion amongst authors. It was in this context that the UK-SCL was seen to have a role.“At all of these meetings there was someone saying ‘it’s too complicated, it just takes too much work, the policies are too confusing and not helpful, can you just make this go away? Or if you can’t make this go away, can you make it easier?”.H-U

Participants involved all felt that busy academics themselves should not feel over-burdened with navigating the policies and processes associated with compliance, but rather should be provided with straightforward solutions:“Ultimately what the institution wants to know is that we are complying with that REF HEFCE policy so that anything we do produce we can potentially submit, and we’re not at risk of losing funding from folks like RCUK if we are not complying with their rules.”RG-EA

Importantly, the implementation of the UK-SCL’s standard licence would not require any additional administrative work on the part of academics.“It’s practical; they’re time-poor, you know, and this is another area of information that is bureaucratic, it’s administrative, and they don’t need to worry about it, you know they’ve got so many other agendas going on.”RG-LA

Payment of APCs for hybrid journals (which were seen as especially expensive) and the resulting perceived ‘double dipping’ by publishers came under particular criticism. The UK-SCL was seen as an alternative approach to maintaining high compliance rates, whilst at the same time facilitating a transition to sustainable open access, at which many OA funder and national policies were ultimately aiming. Some participants were keen to emphasise the need for the licence in the short-term, while the transition was occurring:“So if you have something that’s MRC funded and it should be made open access within 6 months but the publisher only allows open access through the green route after 12 months then you have to publish hybrid. You’re forced to pay an APC.”RG-EA

“We’re presenting … that this is a stop gap, that until we get to a point where we are in a different publishing environment where we haven’t got hybrid, where we haven’t got paywalls, and there’s a different business model, this is how we want to do it…It’s taking the pain away during the transition, whatever that transition is.”RG-EA

“… with the RCUK funding only initially guaranteed for 5 years. You know, there is no guarantee, none of us know what’s going to happen beyond next April, and that’s actually causing a particular challenge at the moment.”RG-EA

“When the Finch Report came out there was this notion of a five-year transition—well we’re at the end of that now and it hasn’t happened. So we want to put something in place that works now,”RG-EA

The frustration evident in these comments was noticeable in many of the participants’ interviews, and also helps to explain why the UK-SCL initiative has gathered momentum in the UK at this particular time. Measures put in place following the Finch Report in 2012, participants explained, had not resulted in the transition to a sustainable OA environment that had been anticipated. The UK-SCL was seen as a way of addressing some of the unsatisfactory and unintended consequences of the Finch Report recommendations.“Again, the funders always said this is supposed to be a transition period, a 5-year transition period, has there been a transition? Well no there hasn’t. Are the funders going to do anything about it? No, they’re going to say, here’s a little bit less money, we are just going to make it awkward for everybody involved, we’re gonna go on for another few years and we’ll see.”H-U

4.2. What Are the Benefits and Challenges of Implementing the Licence?

Participants also highlighted two key areas in which the licence could benefit authors by enabling them to retain control over their own work. Firstly, they would have immediate access to their own outputs for reuse in teaching and research:“As an academic, if your institution has that type of licence, you mostly don’t have to worry anymore about funder policies because as long as you deposit your manuscript with the institution, you will effectively meet all global open access funder requirements.”H-U

Secondly, they would have the ability to retain the freedom to publish where they choose at the same time as meeting OA mandates:“For the authors, I think it’s the fact that they retain their rights to reuse their own work, for research and teaching. I think that’s absolutely essential.”Pre-92-LA

Many participants also felt it would lead to cost savings. The licence would enable immediate open access on publication through the green OA route, ensuring compliance with funders’ policies; it can eliminate the reliance on hybrid journals:“It contributes to preserving academic freedom to publish where academics like. I mention this particularly because publishers often use the argument that policies like those restrict academic freedom; I’d argue the exact opposite.”H-U

However, it was not only the direct cost savings that were cited but also the potential administrative efficiencies and improvements:“A big kind of benefit for this…is hopefully moving away from hybrid open access and not having to pay APCs, because we take the embargoes out.”RG-EA

Open access and open scholarship in general were seen to benefit. Participants emphasised the potential for disseminating material earlier (with the removal of the effect of embargoes), and more widely (with open access as the default for all outputs). Greater visibility for researchers’ outputs would result in broader research benefits:“…doing all the administrative and processing stuff and I think that’s where it’s a benefit to a service…you can free up time for staff to actually do more engagement perhaps, more advocacy around open access and open scholarship.”Pre-92-LA

However, as well as emphasising the anticipated benefits, participants gave equal room to discussing the challenges of implementation, including the possible perceptions of the policy as a complication instead of simplification. An aspect of this response centred on the copyright and IPR:“It will increase the amount of open access material undoubtedly, because it takes the decision, and the processing of open access material out of the hands of the individual academics.”H-U

This again might prove to be particularly challenging due to the ongoing inconsistency between policy and practice surrounding rights, as one participant mentioned:“So academics [are] not really understanding what the point of this licence is and not really understanding what difference it makes to their rights.”RG-LA

“At some point, policy is going to clash with practice and we’ll have academics wondering what on earth’s going on, who probably aren’t at all clear what the [institutional] IP Policy says, even though they’ve said they’ve signed it and read it.”RG-EA

“… the university will grant waivers because we respect that an academic might have different views and we don’t want to make the academic publishing process more painful and difficult than it already is where possible.”H-U

“There is a risk that the publishers will just say ‘well, we want a waiver for all of our stuff’.”H-U

Several of the participants highlighted the relationship dynamics between authors, publishers and the institution, noting that the often-close relationships between author and their preferred journals would need to be taken into account when communicating information about the UK-SCL. Participants were aware that there could be potential for creating tension between institution and publisher, with the UK-SCL being seen as getting in the middle of a long-established author-publisher relationship. This highlighted the need for clear and consistent communication about the rationale for and likely impacts of the licence.“They have databases full of names of authors, they can contact our staff directly because our staff effectively work for them. They’re editors, they’re peer-reviewers, they’re authors…there’s a risk that they could try to engender support for their own cause from our own staff.”RG-EA

“In the library we are slightly concerned that administering the UK-SCL will put additional burden on an already very overstretched team.”Pre-92-LA

The double-sided nature of many of these remarks is notable—benefits of easy compliance and greater control for academics also has the potential to be complicated and confusing for them; and the benefit of service efficiency and sustainability for the library could also become an added administrative burden, at least initially.“I think initially it is probably going to be more work but I’m hoping that eventually it will be less work.”H-U

4.3. How Is the Policy Being Adopted?

“There’s safety in numbers isn’t there? … We didn’t want to do it individually because it’s easier for us to get picked off by people who didn’t support us.”RG-EA

As well as looking for support from a growing number of institutions, it was seen as vital for the project partners in HEIs to gain external support from other organisations, particularly funding bodies:“The more institutions that adopt this, the better it will be and the more persuasive we can be on the issue.”RG-EA

“RLUK have been supportive in offering an endorsement … its useful to have big sector bodies essentially endorsing this or supporting this because I suppose it’s validates what you are trying to do and what you are trying to achieve.”RG-EA

As well as securing strong support from partners, institutions were also focusing on achieving internal buy-in through tailored communications. Ensuring approval from university-level governance bodies for the licence was seen as a particular priority. Many participants felt it was also important to ensure clear understanding of the licence amongst key individuals, prior to meetings, to ensure buy-in:“It’s not just something thought up, it’s actually grounded, it’s got all the authority that it requires. So I think that will help, absolutely.”P1-EA

“… get that buy-in as early as possible from both ways—from the ground-up and the top-down and you know it should be a matter of pushing it out there, confirming it and then putting it through the various committees without too many obstacles.”RG-LA

This response is indicative of the interesting tension at play between collaboration and competition between institutions. Competition could potentially become a secondary driver, if institutions feel they are being left out of a group doing something innovative, they may be encouraged to adopt the licence.“All it will take I can imagine is at Research Committee saying, ‘well this has been adopted by [Institution name]’, I think that will immediately have an impact.”Pre-92-LA

Persuasion of key academics who could then become ‘champions’ was seen as crucial. Throughout, those expecting to adopt the licence focused on involving all stakeholders in the process, and participants were at pains to emphasise this was true of communications with publishers as well:“The most effective way is through their peers … to spread the message as well as it coming down through the website, through emails. The website, which people aren’t going to read, the emails, which people are going to throw away, the conversation over coffee in the SCR, yeah they’re more likely to remember that.”H-U

“We are doing our best to reach out to the publishing community to answer all their questions, as we did when we met, when they brought a string of questions to us.”RG-EA

“… a formal communication to say ‘this is what we’re doing’ and we know that the legal status of the licence as trumping any copyright assignments relies upon the publishers not being able to say they couldn’t reasonably have known about it. So there has to be a big bang.”RG-EA

“It needs to dovetail in with your institutional IP policy. So the two can’t say contradictory things … Some contracts of employment specifically have the policies in the contract, others refer to the policies and then say something like ‘thou shall abide by policies, which from time to time may change’.”RG-EA

However, it was clear that arrangements for setting up more complex processes, such as getting co-author agreements from non-participating institutions, were still being discussed:“The simple example is there’s one academic at an institution writing an article, the publisher is not asking for a waiver, then it’s extremely easy because the academic deposits … the university … simply adds the correct licence, makes the output available when it’s published and case closed.”H-U

“We are thinking about how authors need to gain permission from any co-authors … There’s looking at research collaboration agreements, essentially the contracts that are signed between the institutions … but also within any sort of co-author permission requests, how can we try and attempt to make our academics’ life a bit easier by providing standard texts that they can use.”RG-EA

“We have done an awful lot in terms of providing support to researchers, so currently we’ve got a research data manager, we’ve got a repository obviously, we set up a repository years ago, so we’re doing a lot in terms of open access, we’ve got the mandate.”Pre-92-EA

“Given our very weak open access infrastructure here, I think it would have been quite high-risk for us to be in that first cohort. I mean we haven’t even got a research management system.”Pre-92-LA

“We have worked very hard over the last few years to be seen as peers, and partners, not as a ‘support service’ and we have worked very hard to get ourselves into the lifeblood of the institution.”RG-EA

On the other hand, a number of participants emphasised that they wanted the library to be seen as the part of the institution that was providing solutions for the institution as a whole. The UK-SCL was seen as a solution for the institution to significant current challenges in making open access a reality.“I would hope that it’s not seen as ‘the library’. We’re making it quite clear that this is a university thing, the library is co-ordinating the activity, but … we have university approval for this.”RG-EA

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Declaration of Interest

Appendix A. UK Scholarly Communications Licence and Policy Interview Schedule

- Please can you explain your institution’s approach to the implementation of the UK Scholarly Communications Licence and where you are currently in this implementation process?

- Why has your institution decided upon this particular approach to the UK-SCL?

- What benefits do you anticipate the UK-SCL will bring to your institution and scholarly communications as a whole?

- From your prior knowledge and experience so far, what do you foresee as the possible challenges the UK-SCL may cause?

- What are the practicalities which must be taken into account?

- To what extent has this initiative been driven by the library rather than the university?

- Has your institution been working collaboratively with other institutions or organisations and how has this worked so far?

- What do you believe will be the short and long-term consequences of your institutions implementation of this?

Appendix B. Draft UK-SCL Licence and Model Policy

- Works that are available open access typically receive more citations than equivalent works available only through publisher subscriptions.

- Peer reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings written by UK research academics are covered by numerous policies. Funder policies typically give minimum compliance requirements and are increasingly encouraging researchers to go beyond those. Funder policies are not yet aligned making funder compliance and REF eligibility complex. Publishers, too, have different policies, some of which vary depending on the funding received by the researcher. We’ve called this the “policy stack”.

- This “policy stack” is complex for academics to navigate and administratively complex to manage.

- Enabling the timely communication of the findings of publicly-funded research (thereby increasing citations and impact);

- Supporting academics in meeting funder requirements for open access whilst preserving the right to publish in the journal of choice;

- Allowing academics to retain © in their outputs and, if required by the publisher, to assign © to the publisher;

- Through the automatic granting of a licence, allowing the reuse of research outputs, for example for research and teaching;

- Allowing the accepted manuscript to be made available in digital repositories;

- Enabling compliance with multiple funder policies and REF2021 eligibility through a single action.

- (1)

- Retain the right to make accepted manuscripts of scholarly articles authored by its staff available publicly under the CC BY NC (4.0) licence from the moment of first publication (or earlier if the publisher’s policy allows).

- (2)

- Allow authors and publishers to request a temporary waiver for applying this right for up to 12 months for AHSS and 6 months for STEM (aligned to REF panels).

- (3)

- Where a paper is co-authored with external co-authors, the institution will:

- Automatically sublicense this right to all co-authors credited on the paper and to their host institutions.

- Not apply the licence if a co-author (who is not based at an institution with a UK-SCL-based model policy) objects.

- Honour waiver requests granted by other institutions which have adopted the UK-SCL model policy.

- (1)

- Papers with a single author or co-authors based at UK-SCL institutions:

- There is no additional action required as far as their institution is concerned.

- A publisher may request a waiver (see above) in order to publish the output. The institutions will make a simple workflow available to meet these requests. During an implementation and trial phase, initially for 2018 and 2019, institutions will issue blanket waivers for all publishers who request them, so that authors do not have to take action. This approach will be negotiated and managed centrally and will be reviewed annually.

- (2)

- Papers with co-authors at institutions who have not implemented the UK-SCL:

- Co-author consent for the UK-SCL to apply can be managed using existing mechanisms for managing journal selection, copyright assignment and institutional repository deposit. Institutions will provide simple boiler-plate text to facilitate this process, and will seek to add a relevant clause to research collaboration agreements to facilitate this process in the future. Co-authors need to give their consent for the UK-SCL to apply. This can be managed by what is called ‘estoppel’, i.e., corresponding authors informing their co-authors and taking silence as consent. Institutions will provide simple boiler-plate text to facilitate this process, and will seek to add a relevant clause to research collaboration agreements to facilitate this process in the future.

- During the early implementation of the policy the institution will support the communications with co-authors by seeking consent from co-authors on behalf of staff, by supporting staff through the provision of boilerplate text, or will not require staff to ask co¬authors for consent (& consequently not deposit under the terms of the UK-SCL).

- (3)

- Authors who use content (such as images) with third party rights in their articles:

- The same rules apply as for any deposit in an open access repository: authors are either able to secure the rights to reproduce the content under the licence used by the repository, or to note the elements of the manuscript that are to be made available with a rights reserved statement.

- (4)

- Authors who publish open access already:

- Where an article is published under a CC BY licence by the publisher, the institution will use the open access version of record from the publisher and not the accepted manuscript (which will remain under closed access in the repository).

- (1)

- (University name) is committed to disseminating its research and scholarship as widely as possible. It supports the principle that the results of research should be freely accessible to the public. To enable staffiii to publish their work in a journal of their choice and still meet funder requirements for open access, (university name) adopts the following policy:

- (2)

- Each staff member grants to (university name) a non-exclusive, irrevocable, sub-licensable, worldwide non-commercial licence to make manuscripts of his or her scholarly articles publicly available. This licence is granted on condition that, if (university name) does make the said scholarly articles available, it will only do so on the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial v4 (CC BY NC) licence.

- (3)

- The licence applies to all scholarly articles (including conference proceedings) authored or co-authored while the person is a staff member of (university name) including any third party content where rights in that content have been secured (all for the purposes of this policy “articles”) except for any articles submitted before the adoption of this policy and any articles for which the staff member entered into an incompatible licensing or assignment agreement before the adoption of this policy. It does not apply to monographs, scholarly editions, text books, book chapters, collections of essays, datasets, or other outputs that are not scholarly articles. Upon express and timelyiv direction by a staff member, the (Provost)v or (Provost’s) designate will give every considerationvi to a waiver of the terms of the licence and allow a delay in the public release of the manuscript for a period of up to twelve months from the date of first publication (embargo).

- (4)

- Where this policy applies to an article that is co-authored, the staff member will use all reasonable endeavours to obtain a licence to (university name) from all the co-authors on the same terms as the licence granted under this policy by the staff member. (university name) automatically sub-licenses the rights granted to it under this policy to all co-authors and their host institutions, on condition that if the said co-authors and/or host institutions make a co-authored scholarly article publicly available, they will do so on the terms of a CC BY NC licence. Consequently, the staff member need not seek permission from co-authors employed by institutions that have adopted this policy or other policies that give institutions and/or authors the same rights.

- (5)

- Each staff member will provide an electronic copy of the accepted manuscriptvii (AM) of each article at no charge to the appropriate representative of the (Provost’s) Office in an appropriate format (such as PDF) specified by the (Provost’s) Office. (university name) will deposit the AM in a digital repository, with article metadata usually available immediately upon deposit and the AM being made accessible to the public on the date of first publication (onlineviii or otherwise) under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY NC) licence except where the version of record is published open access and with a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence, in which case the AM will remain on closed deposit. Deposit of other types of scholarly outputs is encouraged but neither required nor included in the licence grant.

- (6)

- Staff members will, when providing the electronic copy of the AM, notify the (Provost’s) Office if any rights or permissions needed to make third party or co-authored content in an article publicly available under a CC BY NC licence have not been secured and which consequently need to be made available with a rights reserved statement.

- (7)

- The (Provost’s) Office will be responsible for interpreting this policy, resolving disputes concerning application, and recommending changes. The (Provost’s) Office shall use all reasonable endeavours to inform publishers and relevant agents of the existence and contents of this policy. The policy will be reviewed annually.

- Interim solution: It remains to be seen how long this policy will remain necessary or appropriate. It may evolve over time following periodic review. For example, under a pure open access publishing model the policy would no longer be necessary.

- This model policy is based on the Harvard Model Open Access Policy—https://osc.hul.harvard.edu/modelpolicy/ (accessed on 22 September 2017) with adjustments to take account of the UK legal framework.

- Staff: The wording here applies to all individuals employed by the university, whether research active or not, who publish scholarly outputs, including students who are considered as “employees” by an institution, and any other persons who have agreed that this policy applies to them by virtue of the terms on which they are engaged by the university or are given access to the facilities and resources of the university.

- Timely: Once the output is made public in the repository the Creative Commons licence cannot be changed retrospectively. Staff should request a waiver at acceptance.

- “Provost” may be replaced with “President”, “Principal”, “Vice Chancellor” etc. as appropriate.

- Every consideration: The waiver addresses concerns authors may have regarding the policy. These include concerns about academic freedom, freedom to accommodate publisher policies, external co-authors with objections to immediate open access, and the like. The university will generally grant waivers but reserves the right to define criteria for conditions under which waiver requests will not be granted (for example when a waiver would put the university under risk of non-compliance with a funder policy).

- Accepted manuscript: The peer-reviewed version of an article that has been accepted for publication in a journal or conference proceeding. The accepted manuscript is not the same as the typeset or published paper. The Funding Councils require deposit of the accepted manuscript to make an output eligible for the REF.NISO definition: http://www.niso.org/publications/rp/RP-8-2008.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2017).HEFCE: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/rsrch/oa/faq/#deposit4 (accessed on 1 September 2017).

- First publication: This policy is intended to align with the HEFCE definition of first publication outlined in Section 4.5 of the HEFCE FAQ http://www.hefce.ac.uk/rsrch/oa/faq/ (accessed on 13 October 2017).

References

- Banks, C. Focusing upstream: Supporting scholarly communication by academics. Insights 2016, 29, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Making Open Access Work for Authors, Institutions and Publishers: A Report on an Open Access Roundtable Hosted by the Copyright Clearance Center Inc. Available online: http://www.copyright.com/content/dam/cc3/marketing/documents/pdfs/Report-Making-Open-Access-Work.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2017).

- Fruin, C. Organization and Delivery of Scholarly Communications Services by Academic and Research Libraries in the United Kingdom: Observations from Across the Pond. J. Libr. Sch. Commun. 2017, 5, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroff, H. Preparing for the Research Excellence Framework: Examples of Open Access Good Practice across the United Kingdom. Ser. Libr. 2016, 71, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J. Accessibility, sustainability, excellence: How to expand access to research publications. Report of the Working Group on Expanding Access to Published Research Findings—The Finch Group. 2012. Available online: http://www.researchinfonet.org/publish/finch/ (accessed on 5 August 2017).

- Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). Policy for Open Access in the Next Research Excellence Framework; Higher Education Funding Council for England: London, UK, 2016; Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/year/2016/201635/ (accessed on 24 February 2017).

- Jubb, M.; Goldstein, S.; Amin, M.; Plume, A.; Aisati, M.; Oeben, S.; Pinfield, S.; Bath, P.A.; Salter, J.; Johnson, R.; et al. Monitoring the Transition to Open Access: A Report for Universities UK; Universities UK: London, UK, 2015; Available online: http://www.researchinfonet.org/oamonitoring/ (accessed on 12 February 2017).

- Jubb, M.; Plume, A.; Oeben, S.; Brammer, L.; Johnson, R.; Bütün, C.; Pinfield, S. Monitoring the Transition to Open Access; Universities UK: London, UK, 2017; Available online: http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/monitoring-transition-open-access-2017.aspx (accessed on 29 January 2018).

- Pinfield, S.; Salter, J.; Bath, P.A. The “total cost of publication” in a hybrid open-access environment: Institutional approaches to funding journal article-processing charges in combination with subscriptions. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 1751–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinfield, S.; Salter, J.; Bath, P.A. A “gold-centric” implementation of open access: Hybrid journals, the “total cost of publication”, and policy development in the UK and beyond. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 2248–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S.C. Open access, publisher embargoes, and the voluntary nature of scholarship: An analysis. Coll. Res. Libr. News 2013, 74, 468–472. Available online: https://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/9008/9804 (accessed on 12 February 2017). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gadd, E.; Troll Covey, D. What does ‘green’ open access mean? Tracking twelve years of changes to journal publisher self-archiving policies. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Björk, B.C. Scholarly journal publishing in transition-from restricted to open access. Electron. Mark. 2017, 27, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, T. The UK Scholarly Communications Licence—Supporting academics with open access. ALISS Q. 2017, 12, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Library. Open Access Policies. Available online: https://osc.hul.harvard.edu/policies/ (accessed on 24 April 2017).

- Carter, I. Executive Summary of Business for Research and Knowledge Exchange Committee: UK Scholarly Communications Licence. 2016. Available online: https://www.sussex.ac.uk/webteam/gateway/file.php?name=rkec-34-05-uk-scholarly-communications-licence.pdfandsite=22 (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- UK-SCL. UK Scholarly Communications Licence and Model Policy. Available online: http://UK-SCL.ac.uk/ (accessed on 3 January 2018).

- Reimer, T. The UK Scholarly Communications Licence—A model for (open access) rights retention. In Proceedings of the 106th German Library Congress, Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 30 May 2017; Available online: https://zenodo.org/record/153928/files/Reimer_UKSCL_OAT2016.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Willinsky, J. Copyright contradictions in scholarly publishing. First Monday 2002, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, J. Facilitating open access: Developing support for author control of copyright. Coll. Res. Libr. News 2006, 67, 219–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suber, P. Open Access [online]; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/open-access (accessed on 21 February 2017).

- Wulf, K.; Newman, S. Missing the Target: The UK Scholarly Communications License. Available online: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/07/26/missing-target-uk-scholarly-communications-license/ (accessed on 1 August 2017).

- Lewis, D.W. The inevitability of open access. Coll. Res. Libr. 2012, 73, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clobridge, A. Open access: Progress, possibilities, and the changing scholarly communications ecosystem. Online Search. Inf. Discov. Technol Strateg. 2014, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pinfield, S. Making open access work: The “state-of-the-art” in providing Open Access to scholarly literature. Online Inf. Rev. 2015, 39, 604–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eve, M.P. Open Access and the Humanities; Cambridge Books Online; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; Available online: https://hcommons.org/deposits/download/mla:290/CONTENT/9781107097896ar.pdf/ (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Ayris, P.; McLaren, E.; Moyle, M.; Sharp, C.; Speicher, L. Open Access in UCL: A new paradigm for London’s global university in research support. Aust. Acad. Res. Libr. 2014, 45, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, D.A. Paying for publication: Issues and challenges for research support services. Aust. Acad. Res. Libr. 2014, 45, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.; Clarkson, N.; Kerridge, S.; McCutcheon, V.; Tripp, L.; Walker, K.; Waller, C. Open Access and the REF: Issues and Potential Solutions Workshop: Executive Summary. 2015. Available online: http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/104395/1/104395.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2017).

- RCUK. RCUK Policy on Open Access and Supporting Guidance; Research Councils UK: Swindon, UK, 2013; Available online: www.rcuk.ac.uk/documents/documents/RCUKOpenAccessPolicy.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2017).

- Kennan, M. Learning to share: Mandates and open access. Libr. Manag. 2011, 32, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, D.A.; Kennan, M.A. Open Access: The whipping boy for problems in scholarly publishing. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 329–350. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Gilchrist, S.B.; Smith, N.X.P.; Kingery, J.A.; Radecki, J.R.; Wilhelm, M.L.; Harrison, K.C.; Ashby, M.L.; Mahn, A.J. A review of open access self-archiving mandate policies. Portal Libr. Acad. 2012, 12, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, B.C.; Laakso, M.; Welling, P.; Paetau, P. Anatomy of green open access. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorn, E.; van der Graaf, M. Towards Good Practices of Copyright in Open Access Journals: A Study among Authors of Articles in Open Access Journals; JISC-SURF: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Available online: https://oerknowledgecloud.org/content/towards-good-practices-copyright-open-access-journals-study-among-authors-articles-open-acce (accessed on 1 August 2017).

- Gadd, E. UK university policy approaches towards the copyright ownership of scholarly works and the future of open access. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 69, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weedon, R. Policy Approaches to Copyright in HEIs: A Study for the JISC Committee for Awareness, Liaison and Training (JCALT); The Centre for Educational Systems: Glasgow, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shashi Nath, S.; Joshi, C.M.; Kumar, P. Intellectual property rights: Issues for creation of institutional repository. DESIDOC J. Libr. Inf. Technol. 2008, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, A.; Coate, K.; Curry, S.; Lawson, S.; Moxham, N.; Røstvik, C.M. Untangling Academic Publishing: A History of the Relationship between Commercial Interests, Academic Prestige and the Circulation of Research; University of St Andrews: Scotland, UK, 2017; Available online: https://zenodo.org/record/546100#.WTK4eKP2bIU (accessed on 26 June 2017).

- Rowley, J.; Johnson, F.; Sbaffi, L.; Frass, W.; Devine, E. Academics’ behaviors and attitudes towards open access publishing in scholarly journals. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S.E.; Wyatt, A. Business Faculty’s Attitudes: Open Access, Disciplinary Repositories, and Institutional Repositories. J. Bus. Financ. Libr. 2014, 19, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Y. University faculty awareness and attitudes towards open access publishing and the institutional repository: A case study. J. Libr. Sch. Commun. 2015, 3, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, D.; Mierzejewska, B.I.; Klein, S. The transformation of the academic publishing market: Multiple perspectives on innovation. Electron. Mark. 2017, 27, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metze, K. Bureaucrats, researchers, editors, and the impact factor: A vicious circle that is detrimental to science. Clinics 2010, 65, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunru, V. The Vicious Cycle of Scholarly Publishing. Available online: https://medium.com/flockademic/the-vicious-cycle-of-scholarly-publishing-eef794937c9c (accessed on 19 November 2017).

- Casadevall, A.; Fang, F.C. Causes for the persistence of impact factor mania. mBio 2014, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Faculty self-archiving: Motivations and barriers. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1909–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, M. Green open access policies of scholarly journal publishers: A study of what, when, and where self-archiving is allowed. Scientometrics 2014, 99, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, H.R. Copyright compliance and infringement in ResearchGate full-text journal articles. Scientometrics 2017, 112, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, E. Academics and Copyright Ownership: Ignorant, Confused or Misled? Available online: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/10/31/guest-post-academics-copyright-ownership-ignorant-confused-misled/?informz=1 (accessed on 9 December 2017).

- Corrall, S. Designing libraries for research collaboration in the network world: An exploratory study. LIBER Q. 2014, 24, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreeves, S.L. The role of repositories in the future of the journal. In The Future of the Academic Journal, 2nd ed.; Cope, B., Phillips, A., Eds.; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 299–315. ISBN 9781843347835. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.; Adams Becker, S.; Estrada, V.; Freeman, A. NMC Horizon Report: 2015 Library Edition; The New Media Consortium: Austin, TX, USA, 2015; Available online: http://cdn.nmc.org/media/2015-nmc-horizon-report-libraryEN.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2017).

- Bowman, S.; Cotter, G.; Herlihy, B.; Noonan, E. It’s not easy being green: Supporting implementation of an open access to publications policy at University College Cork. In Proceedings of the CONUL Annual Conference, Athlone, Ireland, 30–31 May 2017; Available online: https://cora.ucc.ie/bitstream/handle/10468/4070/CONUL2017_Beinggreen.pdf?sequence=2andisAllowed=y (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Keller, A. Library support for open access journal publishing: A needs analysis. Insights 2015, 28, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. New Directions for Academic Libraries in Research Staffing: A Case Study at National University of Ireland Galway. New Rev. Acad. Libr. 2017, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, D. Building scalable and sustainable services for researchers. In Developing Digital Scholarship: Emerging Practices in Academic Libraries; MacKenzie, A., Martin, L., Eds.; Facet: London, UK, 2016; pp. 121–138. ISBN 9781783301102. [Google Scholar]

- Price, E.; Engelson, L.; Vance, C.; Richardson, R.; Henry, J. Open access and closed minds? Collaborating across campus to help faculty understand changing scholarly communications models. In Open Access and the Future of Scholarly Communication: Policy and Infrastructure; Smith, K., Dickson, K., Eds.; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2016; pp. 67–84. ISBN 9781442273023. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, M. No half measures: Overcoming common challenges to doing digital humanities in the library. J. Libr. Adm. 2013, 53, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandegrift, M.; Varner, S. Evolving in common: Creating mutually supportive relationships between libraries and the digital humanities. J. Libr. Adm. 2013, 53, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. Communicating new library roles to enable digital scholarship: A review article. New Rev. Acad. Libr. 2016, 22, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenopir, C.; Dalton, E.D.; Christian, L.; Jones, M.K.; McCabe, M.; Smith, M.; Fish, A. Imagining a gold open access future: Attitudes, behaviors, and funding scenarios among authors of academic scholarship. Coll. Res. Libr. 2017, 78, 824–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. How are universities putting policy into practice, from both library and research perspectives? Insights 2014, 27, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sweeney, D. Working together more constructively towards open access. Inf. Serv. Use 2014, 34, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larivière, V.; Haustein, S.; Mongeon, P. The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, S.; Gray, J.; Mauri, M. Opening the Black Box of Scholarly Communication Funding: A Public Data Infrastructure for Financial Flows in Academic Publishing. Open Libr. Hum. 2016, 2, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, H.; Salhab, J.; Calvé-Genest, A.; Horava, T. Open access article processing charges: DOAJ survey May 2014. Publications 2015, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, D. The UK Government Looks to Double Dip to Pay for Its Open Access Policy. Available online: http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/02/06/the-uk-government-looks-to-double-dip-to-pay-for-its-open-access-policy (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- Bastos, F.; Vidotti, S.; Oddone, N. The University and its libraries: Reactions and resistance to scientific publishers. Inf. Serv. Use 2011, 31, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JISC. SHERPA Services. Available online: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/sherpa (accessed on 9 August 2017).

- Morrison, H. Economics of scholarly communication in transition. First Monday 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frankel, S.; Nestor, S. Opening the Door: How Faculty Authors Can Implement an Open Access Policy at Their Institutions; Science Commons Covington et Burling LLP: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: http://sciencecommons.org/wp-content/uploads/Opening-the-Door.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2017).

- Dawson, P.H.; Yang, S.Q. Institutional Repositories, Open Access and Copyright: What Are the Practices and Implications? Sci. Technol. Libr. 2016, 35, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poynder, R. Open Access and Its Discontents: A British View from Outside the Sciences. Available online: https://poynder.blogspot.co.uk/2017/12/open-access-and-its-discontents-british.html (accessed on 23 February 2018).

- The Publishers Association. Scholarly Communications Licence. Available online: https://www.publishers.org.uk/policy-research/submissions/scholarly-communications-licence/ (accessed on 14 August 2017).

- The Royal Historical Society. The UK Scholarly Communications Licence: What It Is, and Why It Matters for the Arts and Humanities. 2018. Available online: https://5hm1h4aktue2uejbs1hsqt31-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/UK-SCL-March-2018.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2018).

- Jones, S. Developments in Research Funder Data Policy. Int. J. Dig. Curation 2012, 7, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erway, R. Starting the Conversation: University-Wide Research Data Management Policy; OCLC Research: Dublin, OH, USA, 2013; Available online: http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/library/2013/2013-08.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2018).

- Taylor, M. Why Policy Fails—And How It Might Succeed. Available online: https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/matthew-taylor-blog/2016/09/why-policy-fails-and-how-it-might-succeed (accessed on 18 July 2017).

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1452226101. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-0199689453. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curry, S. We Need to Talk about Open Access. Available online: http://occamstypewriter.org/scurry/2012/11/24/we-need-to-talk-about-open-access/ (accessed on 9 January 2018).

- Adema, J.; Stone, G.; Keene, C. Changing Publishing Ecologies: A Landscape Study of New University Presses and Academic-Led Publishing: A Report to JISC; JISC: Bristol, UK, 2017; Available online: https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/6666/1/Changing-publishing-ecologies-report.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2018).

- Dodds, F. The changing copyright landscape in academic publishing. Learn. Publ. 2018, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UKRI. UK Research and Innovation. Available online: https://www.ukri.org/ (accessed on 17 May 2018).

- Pells, R. UK Research Funders Target Hybrid Open Access Charges. The Times Higher Education. 5 March 2018. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/uk-research-funders-target-hybrid-open-access-charges (accessed on 6 March 2018).

- JISC. Discussion Paper: Considering the Implications of the Finch Report Five Years on; JISC Collections Content Strategy Group: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Evolving%20the%20UK%20Approach%20to%20OA%20five%20years%20on%20from%20Finch.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2018).

| Institution Type | Implementation Stage | Contextual Code for Quotations | Number of Participating Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Russell Group | Early adopter | RG-EA | 5 |

| Russell Group | Later adopter | RG-LA | 2 |

| Pre-1992 | Early adopter | Pre-92-EA | 2 |

| Pre-1992 | Later adopter | Pre-92-LA | 3 |

| HEI unaffiliated | N/A | H-U | 2 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baldwin, J.; Pinfield, S. The UK Scholarly Communication Licence: Attempting to Cut through the Gordian Knot of the Complexities of Funder Mandates, Publisher Embargoes and Researcher Caution in Achieving Open Access. Publications 2018, 6, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6030031

Baldwin J, Pinfield S. The UK Scholarly Communication Licence: Attempting to Cut through the Gordian Knot of the Complexities of Funder Mandates, Publisher Embargoes and Researcher Caution in Achieving Open Access. Publications. 2018; 6(3):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6030031

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaldwin, Julie, and Stephen Pinfield. 2018. "The UK Scholarly Communication Licence: Attempting to Cut through the Gordian Knot of the Complexities of Funder Mandates, Publisher Embargoes and Researcher Caution in Achieving Open Access" Publications 6, no. 3: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6030031

APA StyleBaldwin, J., & Pinfield, S. (2018). The UK Scholarly Communication Licence: Attempting to Cut through the Gordian Knot of the Complexities of Funder Mandates, Publisher Embargoes and Researcher Caution in Achieving Open Access. Publications, 6(3), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6030031