Library-Mediated Deposit: A Gift to Researchers or a Curse on Open Access? Reflections from the Case of Surrey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background in the UK: The Shift from Good Practice to Compliance

3. The Case Study: University of Surrey and Open Access

3.1. HEFCE’s OA Policy: A New Workflow for Surrey

- The setup of Symplectic, which harvested published papers after they had been indexed in databases, did not ensure timely compliance with the Research Excellence Framework (REF). It was deemed essential that outputs would be deposited at the point of acceptance, and it was desirable, for the institution’s reporting purposes, that the acceptance date would also be captured.

- Both the consultation with the academics and the review of the systems concluded that the academics engaging with the systems to upload their papers directly involved a high risk of non-compliance.

- Comments from the Faculties strongly suggested that the Library taking over as much of the workload as possible was very desirable.

- A scoping exercise was conducted to develop a business case. Library staff taking over the uploading of the publications was deemed feasible in the short term: at least for the duration of the REF reporting period.

- From 1 April 2016, academics are required to forward the acceptance notification email, attaching their accepted manuscript, to the Library.

- The Library is fully responsible for every step of the process, from manually creating records to applying embargoes to updating metadata on publication. This applies to both outputs in scope and out of scope of the REF.

- The Library, along with the Research & Innovation office, is responsible for raising awareness of the policy and its implications for the next REF.

- In May 2017, the Symplectic Elements publications database was decommissioned because the institution could not rely on auto-harvesting to comply with HEFCE’s open access requirement.

- As a result, the University’s repository changed from a full-text repository to a hybrid publications database/open access repository, i.e., it holds both full-text records and metadata-only records. This led to a steep increase in the size of the repository and an overall increase in the visibility of Surrey outputs; publication records are now public, regardless of whether they hold full text or not. Research dataset records are also public; they are assigned a DOI, but the actual datasets are currently held in other locations that vary by discipline.

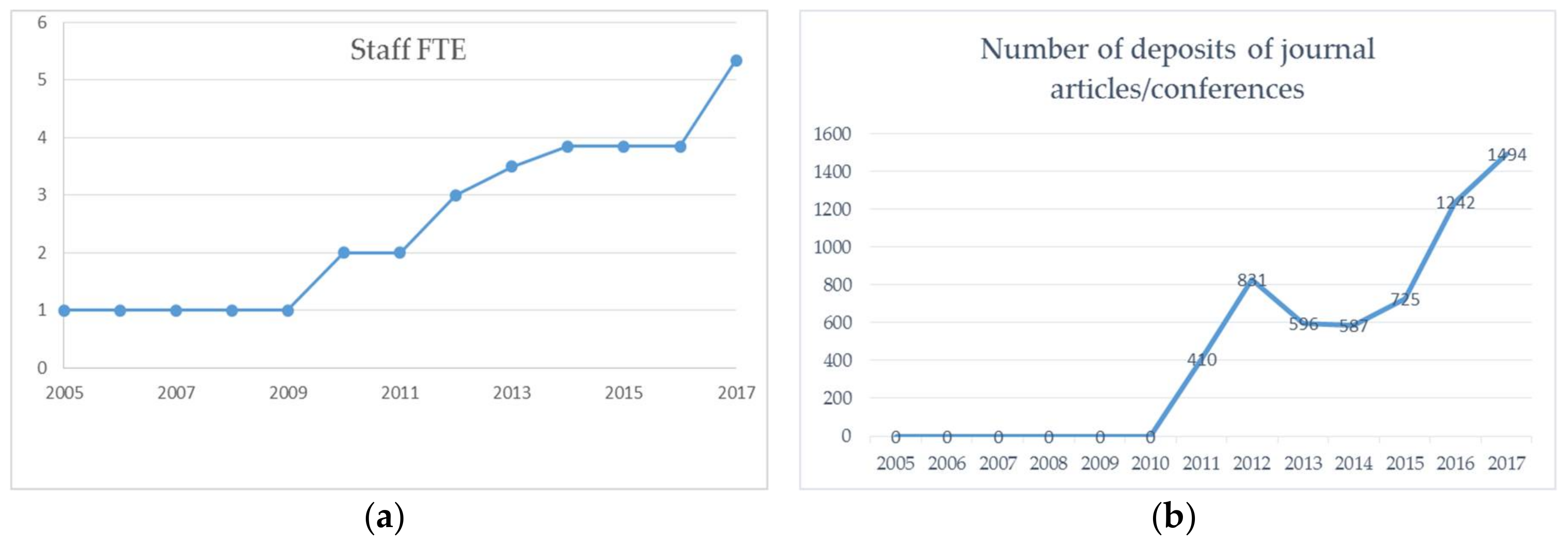

- To meet the resource demands of the new workflow, the Open Access team grew from 1.35 full-time equivalent (FTE) repository manager and 1.5 FTE assistants, to 1.35 FTE repository manager, 1 FTE supervisor, and 3 FTE assistants.

3.2. Effects of the Fully Mediated Workflow

3.3. Discussion of the Fully Mediated Workflow: Benefits and Shortcomings

4. Discussion

4.1. Sustainability Concerns

4.2. Advocates or Compliance Checkers? Evolving Perceptions of the Library, Open Research and Scholarly Communication

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- arXiv.org e-Print archive. Available online: https://arxiv.org/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- CERN. Available online: https://home.cern/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Cogprints. Available online: http://cogprints.org/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Harnad, S. A subversive proposal. In Scholarly Journals at the Crossroads: A Subversive Proposal for Electronic Publishing; Okerson, A., O’Donnell, J., Eds.; Association of Research Libraries: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; ISBN 0-918006-26-0. [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons Science and Technology Committee. Scientific Publications: Free for All? Tenth Report of Session 2003–2004. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200304/cmselect/cmsctech/399/399.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies. Available online: http://roarmap.eprints.org/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Xia, J.; Gilchrist, S.B.; Smith, N.X.P.; Kingery, J.A.; Radecki, J.R.; Wilhelm, M.L.; Harrison, K.C.; Ashby, M.L.; Mahn, A.J. A review of open access self-archiving mandate policies. Portal Libr. Acad. 2012, 12, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellcome Trust Open Access Policy. Available online: https://wellcome.ac.uk/funding/managing-grant/open-access-policy (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- RCUK Policy on Open Access. Available online: http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/research/openaccess/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Finch, J. Accessibility, Sustainability, Excellence: How to Expand Access to Research Publications; Report of the Working Group on Expanding Access to Published Research Findings. Available online: https://www.acu.ac.uk/research-information-network/finch-report-final (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- HEFCE Policy on Open Access. Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/rsrch/oa/Policy/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Vincent-Lamarre, P.; Boivin, J.; Gargouri, Y.; Larivière, V.; Harnad, S. Estimating open access mandate effectiveness: The MELIBEA score. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2815–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, A.; Gargouri, Y.; Hunt, M.; Harnad, S. Open Access Policy: Numbers, Analysis, Effectiveness. Pasteur4OA Work Package 3 Report: Open Access Policies. 2015. Available online: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/375854/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Kim, J. Faculty self-archiving: Motivations and barriers. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1909–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troll Covey, D. Recruiting content for the institutional repository: The barriers exceed the benefits. J. Digit. Inf. 2011, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Boock, M.; Wirth, A.A. It takes more than a mandate: Factors that contribute to increased rates of article deposit to an institutional repository. J. Librariansh. Sch. Commun. 2015, 3, eP1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Nottingham’s Deposit Policy. Available online: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/library/research/open-access/depositing-article.aspx (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- University of Edinburgh’s Deposit Policy. Available online: https://www.ed.ac.uk/information-services/research-support/publish-research/open-access/deposit (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Confederation of Open Access Repositories (COAR). Incentives, Integration, and Mediation: Sustainable Practices for Populating Repositories, 2013. Available online: https://www.coar-repositories.org/files/Sustainable-best-practices_final.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- HEFCE. Circular Letter 33/2017. Initial Decisions on REF 2021. Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/year/2017/CL,332017/ (accessed on 19 February 2018).

- Stern, N. Research Excellence Framework (REF) Review: Building on Success and Learning from Experience. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/541338/ind-16-9-ref-stern-review.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2018).

- Dewey, B.I. The embedded librarian. Strategic campus collaborations. Resour. Shar. Inf. Netw. 2004, 17, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, G.; Bates, J. Envisioning the academic library: A reflection on roles, relevancy and relationships. New Rev. Acad. Librariansh. 2015, 21, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JISC Open Access Pathfinder Project. Available online: https://openaccess.jiscinvolve.org/wp/pathfinder-project-finalised-outputs/ (accessed on 26 March 2018).

| 1 | The increase in the number of assistants was a direct result of the push from senior management to deposit full text in the University CRIS. |

| 2 | The increase in staffing was as a result of managing the RCUK OA fund, but also to cope with the volume of deposits and copyright checking. |

| 3 | An interesting study, beyond the scope of the current one, would be to examine how the online advocacy/information on open access has changed over the years, and how the language used to describe and advocate open access has evolved in response to mandate pressures. |

| Year | New Developments(Internal and External) | Repository Staffing | Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 |

| 1 FTE repository manager | Pilot phase. No established workflow, but papers solicited from early adopters. |

| 2007 |

| 1 FTE | Academic uploads paper in the repository.Library checks copyright and makes the record OA. |

| 2010 | Service is divided into advocacy and copyright checking | 1 FTE repository manager (shared role)1 FTE assistant | Same as above. |

| 2011 |

| 1 FTE repository manager (shared role)1 FTE assistant | Academic approves and uploads full text in Symplectic.Library checks copyright and makes the record OA. |

| 2012 | The Finch report [10] is published. | 1 FTE repository manager (shared role)2 FTE assistant1 plus additional staffing when needed. | |

| 2013 | University receives RCUK OA block fund. | 1 FTE repository manager (shared role)0.5 FTE supervisor role2 FTE assistants | APC workflow introduced. |

| 2014 |

| 1.35 FTE repository manager2 (shared role)0.5 FTE supervisor role2 FTE assistants | E-theses workflow introduced. |

| 2016 | HEFCE policy on OA comes into effect. | ||

| 2017 |

| 1.35 FTE repository manager (shared role).1 FTE supervisor role.3 FTE assistants. |

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daoutis, C.A.; Rodriguez-Marquez, M.D.M. Library-Mediated Deposit: A Gift to Researchers or a Curse on Open Access? Reflections from the Case of Surrey. Publications 2018, 6, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6020020

Daoutis CA, Rodriguez-Marquez MDM. Library-Mediated Deposit: A Gift to Researchers or a Curse on Open Access? Reflections from the Case of Surrey. Publications. 2018; 6(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaoutis, Christine Antiope, and Maria De Montserrat Rodriguez-Marquez. 2018. "Library-Mediated Deposit: A Gift to Researchers or a Curse on Open Access? Reflections from the Case of Surrey" Publications 6, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6020020

APA StyleDaoutis, C. A., & Rodriguez-Marquez, M. D. M. (2018). Library-Mediated Deposit: A Gift to Researchers or a Curse on Open Access? Reflections from the Case of Surrey. Publications, 6(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications6020020