Abstract

Generation Z was the foremost generation to have prevalent access to the Internet from an early age. Technology has strongly influenced this generation in terms of communication, education and consequently their academic information behaviour. With the next generation of scholars already being trained, in a decade, most of the researchers will be mainly digital natives. This study sought to establish the library information resources use pattern in relation to users’ preferred information media in order to render better academic information services to library users. A total of 390 respondents were surveyed at the Nelson Mandela University and the University of Fort Hare using quantitative and qualitative methods. Most of the respondents, 82.3%, were aged between 18 and 23 years; while the average library use time was two hours daily. The most utilised library resource is the Wi-Fi with e-books and e-journals found to be lowly utilised. Records from the E-librarians revealed that undergraduate students account for no more than 6% of total users of electronic databases with 62.3% of the respondents preferring print information resources. Better understanding of library users’ demographics and information media preference is essential in proving the right kind of information services to Generation Z library users.

1. Introduction

The library, generally referred to as the knowledge hub of higher education institutions, is saddled with the responsibility of supporting the teaching, research and community engagement functions especially in the university [1]. The changing demographics of library users and advancement in technological development have also called for a modification in information services provision by libraries and information centres. According to statistics from the Council on Higher Education South Africa, most students enrolled in 2013 were less than twenty-four years old [2], making the demographic mainly Generation Z students. A preponderance of individuals in this generation have widespread access to and use of the Internet and digital media from an early age.

In order to satisfactorily meet the information needs of its users, libraries have inculcated electronic resources into their collections and remote access to information materials as well as the employment of social media in the provision of information services is visible in many academic libraries. Although information resources are widely available on the Internet, the place of the library is still relevant in the selection, acquisition, provision and evaluation of scholarly information resources as well as creating an enabling environment that supports teaching, learning and research functions in the university [3,4]. Several studies have been carried out on the importance and use of academic libraries by students [5,6,7,8]. One of such investigations at the University of Minnesota on the utilization of library resources by first-year college students suggests that first-time, first-year college students who utilize the library have a higher Grade Point Average (GPA) for their first semester and higher retention from fall to spring than those who did not make use of the library [9].

2. Statement of the Problem

In order to render effective library services to the university community, academic libraries are investing hugely into the acquisition of electronic information resources such as e-books, e-journals and the subscription to scholarly databases to facilitate teaching, research and learning. The true value of this huge investment will only be realised through the productive utilisation of these resources. Many libraries have more electronic resources than print information materials as a result of perceived demand for electronic information materials and unlimited access to them at the library and remotely. Previous researches have reported a rise in the preference and use of electronic books [10,11]. This study therefore sought to establish the library information resources utilisation pattern among undergraduate students in selected universities in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa.

3. Research Objectives

The aim of this study was to establish the library information resources use pattern in relation to undergraduate students’ preferred information media in order to render better academic information services to library users. The specific objectives are:

- Assess the library information resources use pattern of undergraduate students;

- Identify the library information resources mostly utilised by undergraduate students;

- Ascertain the textbooks owned and the preferred format of information materials by undergraduate students.

4. Research Hypotheses

The following null hypotheses were tested for this study:

H01:

There is no significant relationship between the number of textbooks owned by undergraduate students and the number of visits they make to the library.

H02:

There is no significant relationship between library’s unprovided information resources and decreased library visit by undergraduate students.

5. Literature Review

Many libraries feel pressured to show their relevance to their user groups as well as parent organisations. These institutions are confronted by increasing operation costs, budget cuts, and more noteworthy pressure to exhibit their success [12]. The Web is replete with unregulated and defective information resources. Because many sources on the Internet are unreliable, even those without expert knowledge in a particular subject can post anything at any time [9]. This has made libraries to stock not just printed resources but electronic digital collections that can be remotely accessed outside its physical walls. A study on the usage of electronic information resources by undergraduate students at a Nigerian university highlighted some of these electronic resources to include digital repositories, e-journals, e-books, scholarly databases and e-library collections which are also supplemented with print resources from the libraries [13,14].

Scholarly electronic libraries and licensed academic databases offer accurate, peer-reviewed information materials to library users that can be collected from a variety of reliable sources. Most academic institutions provide access to online libraries and scholarly databases that are pertinent and contain accurate information; these are less prone to offer information overload as e-libraries may result in increased information literacy skills [1]. Information overload and low relevance of search results are some of the challenges that accompany the access and use of information from commercial search engines. As put forth by Babu, Sarada and Ramaiah [15], e-libraries and licensed scholarly databases are constructed information resource environments, primarily intended to satisfy the information needs of the user community. The manner and extent of use of digital libraries will be greatly influenced by the way they have been constructed [16].

Online library services require many of the same characteristics as traditional reference services: promptness, proper thoughtfulness of the information need, accuracy and courtesy. Users have the opportuneness of retrieving and using information at their own convenience, thereby saving them time and travelling costs, and new choices for answering reference queries [17]. Library services provision via electronic means is not constrained by opening and closing hours as in the case of face-to-face traditional encounters. One of the merits of this medium is that several users can be simultaneously assisted through electronic library services [18].

Over-reliance on Web sources could do more damage than good as many Internet sources have been consistently shown to be inaccurate, biased and unreliable and because “checking the reliability and accuracy of information taken from random sites could take more time than going to the library” [19]; Mashiri [20] opined that using such random sites of information resources for academic work could have a detrimental impact on final grades, stating further that the most important thing is information literacy and using the Web to one’s best advantage. Ayub, Hamid and Nawawi [21] suggested that generic Internet sources alone should never suffice for research work or academic assignment, noting that the most viable alternative for users is always the university’s libraries resources and databases. Most library resources and services leverage on the Internet in providing instructional library services to users. The instructional materials could be in text, pictures or videos and made available on the library website, social media sites or a video-sharing site like YouTube [22], with licensed scholarly databases forming the majority of the electronic reference materials to which academic libraries subscribe.

6. Theoretical Framework

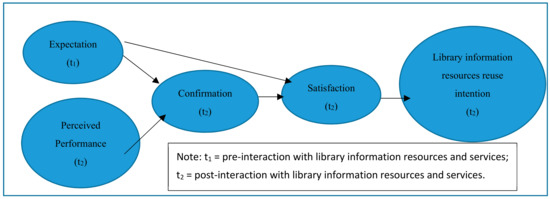

This study is anchored on the Expectation Confirmation Theory (ECT) by [23]. ECT originated from the marketing field and it is widely used in consumer behaviour literature to study consumer satisfaction, post-purchase behaviour and service marketing in general [23,24]. The expectation confirmation theory is made up of five constructs: expectation, performance, confirmation, satisfaction and repurchase intention. It suggests that expectations, alongside perceived performance, results in post-purchase satisfaction [23]. This outcome is intermediated via positive or negative confirmation of expectations by performance. If a product/service beats expectations (positive confirmation), post-purchase gratification will take form. On the contrary, if a product/service fails to meet expectations (negative confirmation), consumers’ dissatisfaction is probable [23,25].

In this study, undergraduate students’ expectation represented what their prospects are about the library and library information resources. A library user will form preconceived perceptions about library information resources before usage as shown in Figure 1. According to ECT, perceptions based on the performance of a product are directly prejudiced by pre-use expectations, and consequently directly impact confirmation or otherwise of opinions and post-use satisfaction of library information resources.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework of expectation confirmation theory for library information resource use (Source: Conceptual framework based on literature reviewed).

After interactions with library information resources, confirmation or otherwise of the preconceived perception is arrived at. These assessments or conclusions are arrived at in comparison to the user’s initial expectations. When a service or product beats the user’s preconceived expectations, the confirmation is positive, which is theorised to increase post-use satisfaction of library information resources. When the outcome is different from the user’s initial expectations, the confirmation is negative, which is suggested to decrease post-use or post-adoption satisfaction of library information resources.

7. Methodology

This study used a survey research design, accompanied by methodological triangulation with quantitative and qualitative data collection. Data was collected through questionnaire and focus group discussion sessions with undergraduate students as well as in-depth interviews with librarians at two selected universities: University of Fort Hare and Nelson Mandela University in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Only undergraduate students who are enrolled for a 3- or 4-year programme at the university that leads to the award of a Bachelor’s degree/diploma were included in this study. First-year students were excluded from the study because they had not stayed long enough on campus when the data were being collected.

The study adopted the stratified sampling procedure. This multifaceted sampling approach begins with the division of the population into strata. Five strata were constituted as follows: Stratum 1: Faculty of Social Science & Humanities/Arts (SSH/Arts); Stratum 2: Faculty of Science & Agriculture; Stratum 3: Faculty of Law; Stratum 4: Faculty of Education; and Stratum 5: Faculty of Management & Commerce/Economic Science (M & C/Eco. Sci.). Five undergraduate degree programmes (see Table 1) were randomly selected from these strata, one from each stratum. The selection process also took into consideration issues of programmes that are common in these faculties to the selected universities and programmes that are offered for a minimum of 3 or 4 years.

Table 1.

Selected universities, faculties, population and sample size.

With the assistance of the Institutional Planning Offices of both universities, the researcher was availed of the complete list of registered students for the 2015 academic session with a total of 11,416 undergraduate students. Calculations from the Raosoft® (Raosoft Incorporated, Seattle, WA, USA) sample calculator with an error margin of 5%, a significant level of 95%, a response distribution of 50% and an estimated population size of 11,416 yielded a minimum effective sample size of 372 participants, and the selected undergraduate degree programmes had a sample of 373 undergraduate students. This was arrived at using the stratified random sampling technique by rounding figures to the nearest whole number (Table 1). The minimum effective sample was calculated just to ensure a minimum number that could adequately represent the population of the study.

A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed as follows: 200 at the University of Fort Hare and 250 at the Nelson Mandela University. More questionnaires were administered at Nelson Mandela University because it has a larger population and a larger sample size than University of Fort Hare. Of the 450 questionnaires administered, 412 were returned, but only 390 were usable, providing an overall response rate of 86.7%. Eight (8) information service librarians at the University of Fort Hare library and Nelson Mandela University library (3 and 5, respectively) were also interviewed while a six-focus-group discussion of between five to eight undergraduate students was also carried out. A test-retest reliability method using Cronbach Alpha was adopted to determine internal consistency, reliability and overall reliability of each of the variables identified in the study. The coefficient alpha for the scale, as a whole, was 0.90.

To ensure that ethical guidelines for research with human subjects were followed, the research proposal was submitted for approval by the Faculty Research and Higher Degrees Committee, University of Fort Hare Research and Ethics Committee and The Research and Ethics Committee at the Nelson Mandela University. The study was judged to have met ethical standards for human subject research, and all ethical procedures of UFH and NMU were followed, culminating in the issuing of an ethical clearance certificates from both universities

8. Analysis and Discussion

Respondents were queried on textbooks owned for modules that they are registered for. It was revealed that 272 (75%) do not have textbooks for the modules that they are registered in, while only 93 (25%) of the respondents responded in the affirmative. On the frequency of library visits, the majority of the respondents, 170 (44.3%), only visit the library occasionally; 105 (27.3%) visit the library almost every day, 59 (15.7%) almost never or never visited the library, while only 50 (13%) use the library every day. The average student in the UK visits the library 57 times a year; a Tab study has revealed [26] and the figures show that, on average, students visit the library twice a week. The amount of time spent using the library showed that most of the undergraduate students (191, 49.9%) use the library for between 1 and 3 h, 86 (22.5%) spend less than 1 h, 86 (22.5%) spend between 4 and 6 h, while 20 (5.2%) spend between 7 and 10 h or more in the library. A report from a study by the Pew Research Centre found that 80% of college students in the United States reported using the library less than three hours each week [27].

The library provides several information services, and makes available to users different information resources. The information resources/services information that undergraduate students use when they visit the library was also queried. The result is displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Information resources/services used by undergraduate students.

Table 2 above reveals that the majority of the respondents rarely/never use e-journals 267 (69.5, 1.70), library databases 216 (56.3%, 1.56) and also, do not consult with information service librarians 280 (72.2%, 1.72). Resources that are also rarely/never used include e-books 267 (69.7%, 1.70), and information literacy/library trainings 324 (83.5%, 1.84). From the mean scores as revealed in Table 2, the most used information resource/service when undergraduate students visit the library is Wi-Fi ( 1.16) while the least utilized service is information literacy/library training ( 1.84). Other frequently used library resources are library books ( 1.43), and computer laboratories 244 ( 1.37). Research findings which corroborate this result [28,29] noted that on information search strategies, especially as it relates to academic materials, the use of scholarly databases, university library Web resources, e-learning resources and university library publications is still low. This was also confirmed in a study of undergraduate students’ Internet access and use were it was reported that 10% of the study population uses discussion facilities [30].

Although 83.5% of the respondents reported using the Wi-Fi when they visit the library, its use, according to Table 2, is not to access e-journals, use library databases or e-books. Some of these respondents may be using open Web resources as reported in a study of undergraduate information resource choices Ursinus College [31]. Qualitative reports from the focus group session reveal that many students do not evaluate the information resources they obtain from the Internet. This may be as a result of lack of information literacy skills as only 16.5% attend information literacy/library training programmes. During the focus group session, a few respondents stated that they evaluate the information they get when they search the Internet with Google. “Yes, because we’ll be penalised by our lecturers. Everything you use, you have to validate. The author, journal and date of publication are some of the ways we were taught to evaluate information from the Internet” (Student Focus Group Discussion, February 2016). Another respondent said, “I usually compare it with something else if they agree, then I use it. Even if the work is written by someone from another profession, as long as it is relevant, I’ll use it” (Student Focus Group Discussion, February 2016). Others do not make effort to evaluate their sources as a student stated, “I don’t check the authority or credibility of the sources of the information from the Internet. As long as it is relevant. I only check for the author when there is need for referencing” (Student Focus Group Discussion, February 2016). Another student noted, “Once the information is useful, I just use it. I don’t even care about the authority because I don’t know how to check if the author has the right expertise or knowledge” (Student Focus Group Discussion, February 2016).

This report resonates with findings from Baro and Fyneman’s [32] study of information literacy among undergraduate students. The need to train students on the use of electronic information resources was also pointed out in a study on undergraduate students at the Redeemer’s University in Nigeria [22]. A study also observed that the students’ visit to the library was to use electronic resources such as computers as students often wait in line to use computers at peak times during the semester [33]. A service also revealed to be of low use by library users is library training/information literacy services. Lack of library training and information literacy skills (Table 2) could bring difficulty in finding relevant academic information materials. A participant during the focus group discussion (FGD), when asked of library training attendance, responded “NO” when asked whether they had attended any information literacy training. “I only came for library tour in first year”. Another opined that “consulting the librarian is slower, Google is instant” (Student Focus Group Discussion, February 2016). In a study of undergraduate students’ perception and selection of information sources, it was revealed that Web search engines were the most selected information source/channel and the least was librarians [31]

In view of the dynamic nature of information materials as well as the demand and availability of other formats other than print resources, respondents were requested to specify their preferred format of information materials. This is shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Preferred information resource format.

From Table 3 above, it is evident that undergraduate students prefer information resources in print format 297 (77.1%), thus making print resources still very popular among Generation Zs despite the move towards e-resources. Less than half of the respondents preferred information materials in electronic formats (e-books and e-journals) 139 (36.1%). Previous researches have also reported students’ preference for print information resources [32,33,34]. Many libraries have as many electronic resources as print resources. This was confirmed during the interview session at the University of Fort Hare Libraries, where a librarian noted, “we have more electronic information resources than the printed information resources on the shelf”. Lower use of electronic resources over print resources was also reported at the Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria [35]. A 2016 Nielsen survey in the UK on the sale of published books reported a 4% decline in the sales of e-books, the second consecutive year digital books had shrunk while the sales of printed books rose 7% [36]. A survey on young adult readers’ book format preference reported that 62% of 16–24-year-olds prefer print information materials over their electronic equivalents [37]. Students’ dissatisfaction and frustration with e-textbook formats has also been reported [38]

However, several researches suggest no significant difference in academic attainment in studies comparing print textbooks vs. electronic versions [39,40,41], although mean score was somewhat higher for respondents using printed textbooks [41]. The result from the focus group session also reveals that most of the respondents still prefer printed information resources to electronic ones. A respondent from the focus group noted that preferred information format is print: “you can highlight, and it is more handy” (Student Focus Group Discussion, February 2016). In a large e-book survey conducted by the JISC National E-Book Observatory, academic staff and students felt that online access and searchability were the biggest advantages of e-books [42].

The library exists to meet the information and educational needs of its service communities; hence, respondents were asked if they have ever requested any information material that the library could not provide. Most of the respondents who make use of the library/library information resources stated that every information material they request from the library has been provided 241 (62%), while many of the undergraduate students 148 (38%) said that they have requested information materials that the library could not provide. Studies have shown the use of library information resources despite these shortcomings [43,44].

9. Hypotheses Testing

The following null hypotheses were tested to determine if the observations that were reported have occurred based on statistics.

Null Hypothesis 1:

There is no significant relationship between the number of textbooks owned by undergraduate students and the number of visits they make to the library.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance for textbook ownership and library visit.

Table 5.

Regression coefficient.

From the table above, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test shows that F = 4.710, df = 363 and p = 0.031. Since p-value < 0.05, this shows that the number of times undergraduate students visit the library has a significant relationship with the number of textbooks that they own.

The result from Table 5 above shows that the regression coefficient for frequency of library visits is −0.052, which indicates that for every increase in undergraduate students’ visits to the library, there is a decrease of 0.052 in the number of textbooks owned for the courses or modules registered. From the above result, it can be inferred that undergraduate students with fewer textbooks visit the library more (B = −0.113, t = −2.170, p < 0.05). Although 70.4% of the respondents reported visiting the library to study with personal book, a significant population (57.4%) of the respondents always visit the library to study using library books. Studies have also indicated increased use of library materials for study purposes in academic libraries among students [45,46]. This quantitative result also corroborates the results from the focus group where some of the respondents said they visited the library to read or borrow recommended textbooks for their school work, “I do borrow books from the library that my lecturers have recommended for a particular module”, and a participant noted that “sometimes when I visit the library, I borrow books that I cannot afford but are relevant to my academic work” (Student Focus Group Discussion, February 2016).

Null Hypothesis 2:

There is no significant relationship between library’s unprovided information resources and decreased library visit by undergraduate students.

It is assumed that the failure of libraries to provide users with the information resources they utilise mostly may lead to a decrease in the number of visits to the library. This decrease in library visits may be due to perceived performance or dissatisfaction with expectations as suggested by ECT. This hypothesis was tested and the result is revealed in Table 6 and Table 7 below.

Table 6.

ANOVA for unprovided information resources and library visit.

Table 7.

Regression Coefficient.

From Table 6 above, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test shows that F = 6.468, df = 382 and p = 0.011. Since p-value < 0.05, this shows that the library’s failure in providing an information material for students has a significant effect or relationship with the frequency of library visits.

As shown in Table 7, for every increase in the number of times the library is unable to provide an information material, there is a decrease of 0.026 in undergraduate students’ frequency of visits to the library. It can, therefore, be concluded that users visit the library less when the library is unable to make needed information materials available. The result reveals that there is a significant relationship between unprovided information materials by the library (B = −0.260, t = −2.543, p < 0.05) and the frequency of library visits. Simmonds and Andaleeb [47] opined that when library service quality is poor, the utilisation of library resources and services by clienteles will also be negatively affected.

10. Conclusions

This study addressed the issue of library information resources use among Generation Z students, the information materials owned by the students and the provision of needed information resources by the library. This study explicated the state of undergraduate students’ position on the use of library information resources as well as the view of information librarians on students when utilising and seeking academic information.

Despite 75% of the respondents not having textbooks for the modules they are registered for, only 13% of the population sample visit the library daily with the majority of the students (170 or 44.3%) being occasional users, while as little as 5.2% of the respondents use the library for between 7 and 10 h or more. This average of two hours that is spent in the utilization of library information resources can be concluded to be spent mainly on accessing Wi-Fi, as it is the most used library resource among respondents. While information literacy is the least utilised library service by undergraduate students, this is not surprising as many of the respondents indicated during the focus group discussion sessions that they do not evaluate most information resources they obtained from the Internet, with many of the students not having the skills needed to evaluate these resources.

Moreover, consulting with the information services librarian (faculty librarians) for help with assignments and guidance with relevant discipline-based information resources is not a service that most undergraduate students utilise. Librarians believe that since it is the information age, electronic resources should be provided more as a librarian noted during the interview session that “we have more electronic information resources than available print materials on the shelf”, and there were several suggestions from librarians that “more electronic information resources should be provided”. This suggestion is in contrast with most undergraduate library users who still prefer the use of print information resources. The use of electronic databases and e-journals is also very poor among undergraduate students. E-books are rarely/never used (267 or 69.7% of the respondents) despite Wi-Fi being the most utilized library resource among Generation Z students. Furthermore, although the Internet and digital information media has become a major component of Generation Z students, print information resources are still better preferred to electronic versions. This explains why the use of e-books is still unpopular with many users when they visit the library. Most e-book databases require specialized readers to be installed into the computers, and printing is limited to a certain number of pages. This could be one of the reasons why printed information resources are still very common among undergraduate students.

The majority of respondents (62%) noted that the libraries have provided them with requested information resources. Despite the libraries providing most of the respondents with needed information resources, the libraries have also not been able to provide needed information resources to as many as 38% of the students. Previous researchers have identified monetary shortfall as one of the major challenges bedeviling libraries in the acquisition of information resources [12,48]. Inferential statistical finding reveals that students with fewer books make more visits to the library. As reflected in Table 2, most of the respondents visit the library to study using library books/print journals (218 or 57.4%) while as many as 272 or 70.5% of the respondents make use of past examination questions, dictionaries and encyclopaedias at the library. This indicates that library users still rely on the library for information resources that are not within their reach.

Further results from the inferential statistics also revealed that there is a decrease in the number of times undergraduate students visit the library when the library is unable to provide requested information materials. Although the libraries cater to the information needs of most users, 38% of respondents who have had dissatisfaction with the library for not providing them with needed information resources is a staggering figure.

11. Recommendations

From the above conclusions, the recommendations are put forth as reflected by the respondents. Most of the suggestions made by respondents in the qualitative section of the questionnaire were mainly on the provision of more/newer books (118 or 30%), and an increase in the amount of time for books on short-term loans (21 or 5.4%). An extension of library opening hours (24 h during examination periods) and library training/guides on how to use the library (22 or 5.6%) were also highlighted.

Librarians should be familiar with the information needs and preferred format of information resources of their users and not just acquire information resources as a result of popular trend so as to adequately cater for the needs of the library users.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre of the University of Fort Hare for partly funding the study.

Author Contributions

Oghenere Gabriel Salubi collected and analysed the data for this study. He also contributed to the final writing of the manuscript. Ezra Ondari-Okemwa supervised the writing of the proposal for the study and also drafted the instruments that were used to collect the data. Fhulu Nekhwevha worked on the theoretical and conceptual aspect of the study of the study. He supervised the final writing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors are not aware of any conflict of interest.

References

- Schmidt, J. From Library to Cybrary: Changing the Focus of Library Design and Service Delivery. In Libr@ries: Changing Information Space and Practice; Cushla, K., Bertram, B., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Council on Higher Education. 2013 Higher Education Data. Available online: http://www.che.ac.za/focus_areas/higher_education_data/2013/participation#age (accessed on 31 July 2017).

- Shelburne, W.A. Library Collections, Acquisitions & Technical Services E-Book Usage in an Academic Library : User Attitudes and Behaviors. Libr. Collect. Acquis. Tech. Serv. 2009, 33, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Christianson, M.; Aucoin, M. Electronic or Print Books : Which Are Used ? Libr. Collect. Acquis. Tech. Serv. 2005, 29, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, M.; Wilkinson, F.C. The Academic Library Impact on Student Persistence. Coll. Res. Libr. 2011, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, A.; Middleton, M. The Relationship between Academic Library Usage and Educational Performance in Kuwait. Libr. Manag. 2012, 33, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmire, E. Academic Library Performance Measures and Undergraduates’ Library Use and Educational Outcomes. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2002, 24, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.H.R.; Webb, T.D. Uncovering Meaningful Correlation between Student Academic Performance and Library Material Usage. Coll. Res. Libr. 2011, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, K.M.; Fransen, J.; Nackerud, S. Library Use and Undergraduate Student Outcomes: New Evidence for Students’ Retention and Academic Success. Libr. Acad. 2013, 13, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, C.; Thomas, M. A Survey Experience from the Academic Library Trenches. Idaho Libr. Assoc. 2013, 64, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, B.; Hassan, B. Incorporating Information Technology in Library and Information Science Curriculum in Nigeria: A Strategy for Survival in the 21st Century. Available online: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/447/ (accessed on 12 April 2018).

- Kingma, B.; McClure, K. Lib-Value: Values, Outcomes, and Return on Investment of Academic Libraries, Phase III: ROI of the Syracuse University Library. Coll. Res. Libr. 2015, 76, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand, O.A.; Ruth, E.O.; Paul, O.E. Usage of Electronic Information Resources (EIRs) by Undergraduate Students of Federal University of Petroleum Resources Effurun. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 5, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Print vs. Electronic Resources: A Study of User Perceptions, Preferences, and Use. Inf. Process. Manag. 2006, 42, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.S.; Sarada, B.; Ramaiah, C.K. Use of Internet Resources in the S.V. University Digital Library. DESIDOC J. Libr. Inf. Technol. 2010, 30, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, H. Virtual Libraries Supporting Student Learning. Sch. Libr. Worldw. 2002, 8, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sampath Kumar, B.T.; Kumar, G.T. The Electronic Library Perception and Usage of E-Resources and the Internet by Indian Academics. Electron. Libr. Iss Electron. Libr. Iss Electron. Libr. 2010, 28, 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, A. Web-Based Library Services. In 3rd Convention PLANNER -2005, Assam University, Silchar; Assam University: Ahmedabad, India, 2005; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Waithaka, M.W. Internet Use among University Students in Kenya: A Case Study of the University of Nairobi. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mashiri, E. First Year and Final Year Undergraduate Students’ Academic Use of Internet. Case of a Zimbabwean University. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 3, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ayub, A.F.M.; Hamid, W.H.W.; Nawawi, M.H. Use of Internet for Academic Purposes among Students in Malaysian Institutions of Higher Education. Turkish Online J. Educ. Technol. 2014, 13, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Adeniran, P. Usage of Electronic Resources by Undergraduates at the Redeemers University, Nigeria. Int. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 5, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model for the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Cognitive, Affective, and Attribute Bases of the Satisfaction Response. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabolkar, P.A.; Shepard, C.D.; Thorpe, D.I. A Comprehensive Framework for Service Quality: An Investigation of Critical Conceptual and Measurement Issues through a Longitudinal Study. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 139–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkin, T. Revealed: How Much Time Do You Spend in the Library? Available online: http://thetab.com/2014/05/23/how-nerdy-is-your-uni-14073 (accessed on 21 February 2017).

- Jones, S. The Internet Goes to College: How Students Are Living in the Future with Today’s Technology; Education Resources Information Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muniandy, B. Academic Use of Internet among Undergraduate Students : A Preliminary Case Study in a Malaysian University. Int. J. Cyber Soc. Educ. 2010, 3, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bharati, P.; Chaudhury, A. An Empirical Investigation of Decision-Making Satisfaction in Web-Based Decision Support Systems. Decis. Support Syst. 2004, 37, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunmisi, S.R.; Ajala, E.B.; Iyoro, A.O. Internet Access and Usage by Undergraduate Students: A Case Study of Olabisi Onabanjo. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2013, 1–10. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com.hk&httpsredir=1&article=2191&context=libphilprac (accessed on 12 April 2018).

- Mill, D.H. Undergraduate Information Resource Choices. Coll. Res. Libr. 2008, 69, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baro, E.; Fyneman, B. Information Literacy among Undergraduate Students in Niger Delta University. Electron. Libr. 2009, 27, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Johnson-yale, C.; Millermaier, S.; Seoane, F. Internet and Higher Education Academic Work, the Internet and U.S. College Students. Internet High. Educ. 2008, 11, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Sin, S.C.J. Perception and Selection of Information Sources by Undergraduate Students: Effects of Avoidant Style, Confidence, and Personal Control in Problem-Solving. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2007, 33, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboola, I.O. Use of Print and Electronic Resources by Agricultural Science Students in Nigerian Universities. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2010, 32, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, S. Ebook Sales Continue to Fall as Younger Generations Drive Appetite for Print. The Guardian. London March 14. 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/14/ebook-sales-continue-to-fall-nielsen-survey-uk-book-sales (accessed on 17 April 2018).

- Falc, E.O. An Assessment of College Students’ Attitudes towards Using an Online E-Textbook. Interdiscip. J. E -Learning Learn. Objects 2013, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bury, L. Young Adult Readers “Prefer Printed to Ebooks”. The Guardian. London November 25. 2013. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/nov/25/young-adult-readers-prefer-printed-ebooks (accessed on 17 April 2018).

- Murray, M.C.; Pérez, J. E-Textbooks Are Coming: Are We Ready? Issues Informing Sci. Inf. Technol. 2011, 8, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McFall, R. Electronic Textbooks That Transform How Textbooks Are Used. The Electron. Libr. 2005, 23, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepperd, J.A.; Grace, J.L.; Koch, E.J. Evaluating the Electronic Textbook: Is It Time to Dispense with the Paper Text? Teach. Psychol. 2008, 35, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, H.R.; Nicholas, D.; Rowlands, I. Scholarly E-Books: The Views of 16,000 Academics: Results from the JISC National E-Book Observatory. Aslib Proc. New Inf. Perspect. 2009, 61, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, E.; Stone, G. Understanding Patterns of Library Use Among Undergraduate Students from Different Disciplines. Evid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2014, 9, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.; Collins, E. Library Usage and Demographic Characteristics of Undergraduate Students in a UK University. Perform. Meas. Metrics 2013, 14, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Q.G.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Perfectionism and Library Anxiety Among Graduate Stuents. J. Acad. Librariansh. 1998, 24, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, D.R.; Weber, J.E. Towards Assessing in-House Use of Print Resources in the Undergraduate Academic Library: An Inter-Institutional Study. Libr. Collect. Acquis. Tech. Serv. 2000, 24, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, P.L.; Andaleeb, S.S. Usage of Academic Libraries: The Role of Service Quality, Resources and User Characteristics. Libr. Trends 2001, 49, 626–634. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C.; Terras, M.; Galina, I.; Huntington, P.; Pappa, N. Library and Information Resources and Users of Digital Resources in the Humanities. Progr. Electron. Libr. Inf. Syst. 2008, 42, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).