1. Introduction

Scholarly journals published in English have for a long time been the main medium for global scholarly communication. The report from the STM Association estimates that there were about 28,100 active peer-reviewed English-language journals in late 2014, more than four times the number of journals published in other languages [

1]. There is also an increased demand from non-native English-speaking researchers to publish in English-language journals, which is corroborated by the evidence that the number of publications originating from non-English speaking countries is on the rise [

2,

3]. Chinese scientists, for example, have over the last two decades increasingly written excellent academic papers in English, and published them in journals from leading international publishers [

4]. The underlying motivations behind non-native English-speaking researchers are almost consistent across geopolitical contexts and are indeed multifarious [

3]. It is partly an effect of national policies to assess research productivity and performance, which give greater prominence to publications in mainstream English-language journals. As such, researchers tend to opt for these journals as optimal publishing outlets so that they can satisfy one of the most important criteria for research assessment. Despite linguistic difficulties faced by researchers using English as a foreign language, they choose to invest their time and efforts to write their best work in English for publication in international mainstream journals that can lead to further rewards such as recognition, prestige, and career development [

3,

5,

6]. The desire to communicate the research results to the international academic community and enhance the impact of the published papers can also be a driving force for researchers deciding to publish in English-language journals, as papers written in English are more likely to be cited [

7]. For all these reasons, scholarly journals publishing in native languages aside from English are in danger of losing high-quality academic papers authored by domestic researchers, which will lead to a decline in journal impact and poses a challenge to the survival of such journals.

The dominance of English-language journals published by the major, predominantly Anglo-American, publishers in the worldwide scholarly publishing market has made the Chinese government realise the urgent need for the development of China’s own English-language journals. In recent years, such journals have attracted keen interest and active support from the government in line with an apparent determination to extend the international influence of local science and technology journals, thereby raising the country’s international profile in the scientific community [

8]. By 2016, more than half of 239 China’s English-language scientific journals were indexed in the Science Citation Index (SCI) [

9]. The continuous growth of English-language journals in China can be viewed as a major step towards overcoming linguistic barriers in order to gain better international visibility and reach a wider international readership, and therefore stem the flow of high-quality manuscripts written by local researchers to non-Chinese publishers [

10,

11]. The rise of China’s English-language journals, nevertheless, makes the development of Chinese-language scholarly journals increasingly difficult.

The emergent open access (OA) publishing model, made possible in the digital age, seems to offer a great opportunity for traditional journals published in languages other than English. OA publishing partly addresses non-native English-speaking researchers’ concerns over limited visibility and international circulation (and as a consequence the lower impact of scholarly work if published in such journals) caused by closed access and linguistic disadvantages [

12]. The increased visibility and impact of Latin American publications through various OA programs such as the development of regional OA publishing platform SciELO [

13] illustrate this [

14,

15]. The share of gold OA journals in Scopus for Latin America is much higher at 74%, compared to 9% of all journals in that index [

16]. In connection with the adoption of the OA publishing model as a solution to the distribution challenges faced by traditional journals in languages other than English, their publishers may even consider directly converting their journals into English or multiple languages to transcend national boundaries so that linguistic hurdles are no longer an issue [

17].

English-language OA scholarly journals remain dominant in the global OA publishing market. In the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), only 24% of included journals are in other languages [

18]. It is, however, worth stressing that the DOAJ selects OA journals on the condition that they satisfy the most stringent Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI) definition of OA [

19], therefore, non-English language journals that offer free access to content but no reuse rights granted by the Creative Commons [

20] or similar licenses are not accepted for inclusion. Since major studies on OA tend to use DOAJ, often in combination with Web of Science (WoS) [

21] and/or Scopus [

22], as the basis for data collection, they often exclude many non-English language OA journals from developing countries. A few descriptive studies have been carried out to examine the situation of scholarly OA publishing in countries without a substantial international publishing industry, where journals published in the local languages occupy an important role [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Nevertheless, there is a clear lack of empirical research focusing on OA journals in languages aside from English and reviewing their development in response to the changing global scholarly journal landscape.

In this article, a case study of Chinese-language OA journals is reported. In terms of research strength, China has in recent years completed the transition from being predominantly a consumer of science to a major producer, becoming the world’s second largest contributor to research output [

27]. In 2014, the numbers of papers authored by Chinese scientists in the SCI and Engineering Index (EI) were 263,500 and 172,900, accounting for 14.9% and 31.6% of the total in the respective databases [

28]. Based on the data from UlrichsWeb, the global scholarly publishing market was estimated to include 76,294 peer-reviewed journals as of May 2017. Of that number, Chinese publishers take the third largest share at 12% behind the US (28%) and the UK (18%) [

29]. Despite China having gained a competitive advantage in the number of published scholarly journals over most other countries, its domestic market continues to be dominated by Western publishers. According to the STM report, international publishers claimed a market share of about two-thirds of the Chinese STM market in 2014 [

1]. In addition, China’s growth of research citations is dramatic, reflecting an improvement in the visibility and impact of scholarly papers authored by Chinese researchers [

30].

The open access movement in China has witnessed some progress due to all kinds of support from the Chinese government, funders, libraries, and scientific communities. The major achievements are, for example, the participation in the Sponsoring Consortium for Open Access Publishing in Particle Physics (SCOAP3) and the announcement of the Open Access Strategy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). Although there are not yet many formal strategies and operational policies related to gold OA in China, it is anticipated that the number of domestic journals using the OA model will grow [

31]. Therefore, the current position of the Chinese-language OA journal market is an issue which merits discussion. In fact, for this study it was almost a prerequisite that the author be from China, because, for instance, all of the participants in the qualitative part wished to conduct the interviews in Chinese. This study begins by identifying the major characteristics of the market. It then goes on to explore key motivations behind Chinese-language OA publishing and perceived barriers, reporting a set of semi-structured interviews with members of the Chinese publishing community. Last, it proposes some recommendations for the future development of the Chinese-language OA journal market.

The specific research questions of this study were as follows:

- RQ1:

What are the main characteristics of the Chinese-language OA journal market (number of journals, distribution across types of publishers, distribution across subject fields, distribution of subject fields across types of publishers, and distribution across year of launch)?

- RQ2:

What is the percentage of Chinese-language OA journals indexed in DOAJ, Scopus, Web of Science (WoS) and Directory of Open Access Scholarly Resources (ROAD)?

- RQ3:

What motivated the interviewed publishers of Chinese-language OA journals to adopt an OA approach?

- RQ4:

What do the interviewed OA publishers perceive as the major barriers for successful publishing of Chinese-language OA journals?

- RQ5:

What are attitudes of the interviewed Chinese-language OA journal publishers to converting their journals into English or bilingual journals, and what are perceived as the main barriers to such a conversion?

3. Methods

This study consists of a quantitative and a qualitative part. The quantitative part was used in the first phase to identify the situation of the Chinese-language OA publishing market through a descriptive bibliometric analysis to answer RQ1–RQ2. This was followed by qualitative in-depth interviews with publishers of Chinese-language OA journals to explore RQ3–RQ5, where their key motivations to OA, barriers to publishing journals, and attitudes as well as barriers to converting into English or bilingual OA journals were evaluated.

The China Open Access Journals (COAJ) index was used to search for OA journals published in the Chinese language. The COAJ index, initially an OA portal of the Chinese Academy of Science for its affiliated scientific journals, has since 2010 expanded targeting to become a national index for all scholarly OA journals from China [

44]. The COAJ index uses the BOAI definition of OA, which in addition to free full text access also requires extensive reuse rights for readers commonly granted by the scholarly publishers under Creative Commons licenses. It is, however, necessary to draw attention to the fact that its inclusion criteria applied to each individual journal’s application do not cover the questions regarding copyright and licensing issues, so OA in this study refers solely to free electronic access to articles published in scholarly journals. It is likely that there are some Chinese OA journals existing outside this index; however, a search on the Internet for such journals is a very time-consuming manual task. For the purpose of this study, it is believed that COAJ is still a suitable journal index that has covered the majority of the target population.

All journal information was harvested from the COAJ index during August 2016. Using the “Language” field as a filter, English-language OA journals and bilingual OA journals (Chinese and English) were excluded in the next step. The data gathered included “Chinese title”, “ISSN”, “CN-ISSN” “Publisher”, “Subject” and “The established year”. Some data was manually collected from the journal’s website if it was not available in the COAJ index. The entities “Publisher” and “Subject” were further coded using the same classification as in two earlier international OA studies [

45,

46]. It is noted that the “general” category represents the subject areas of journals encompassing more than one classified discipline.

The eight participants in the interviews were selected based on some previous contacts of the researcher and by suggestions received during the first interviews. All participants met three selection criteria: they were knowledgeable about OA publishing, worked for Chinese-language OA journals, and currently managed or played active roles in the operation of the journals.

Table 1 shows that the participants are from major types of publishers in various subjects and sizes, and that most of them are senior executives. Data was collected through semi-structured online interviews held in either Shanghai or Finland between October and December 2016, after informed consent was obtained from each participant. The interviews were carried out in Mandarin Chinese, lasting on average 40 min, and they were then transcribed into English. The interviews aimed for a more comprehensive understanding of the results of the bibliometric analysis. In the following reporting, participant was a term used to describe those who were interviewed.

4. Results

4.1. Number of Journals and Share Indexed in DOAJ, WoS, Scopus and ROAD

In total, 595 out of the 654 OA journals indexed by the COAJ index published the full texts of their articles in Chinese only, suggesting a dominance of Chinese-language journals among the country’s OA journals. The share of these 595 journals that are currently included in DOAJ, WoS and Scopus, are 1%, 1%, and 19% respectively. None of these journals are indexed in ROAD.

4.2. Types of Publishers

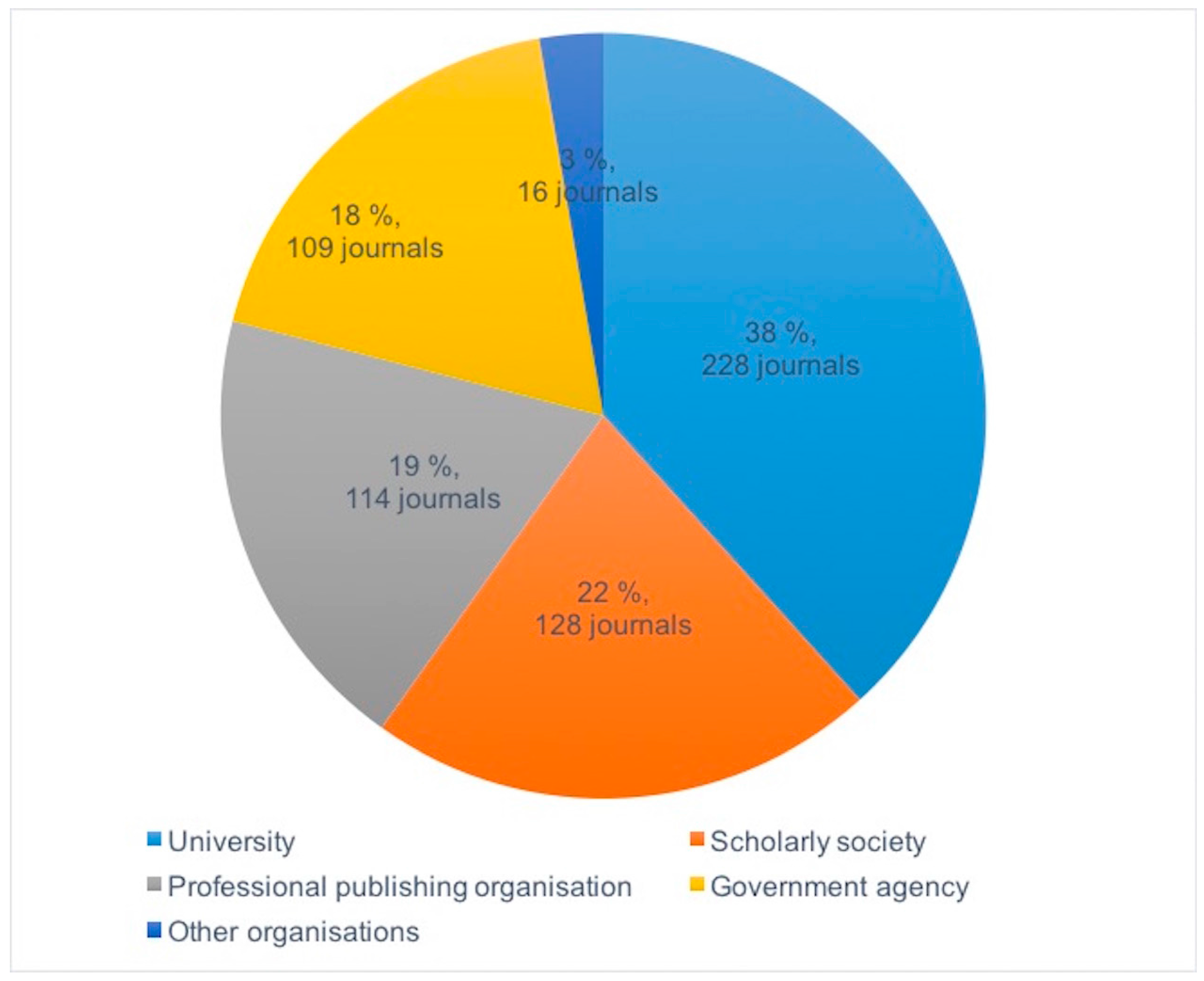

Figure 1 presents the distribution of the 595 journals across different types of publishers. University-published journals formed the largest category (40%, 228 journals). Three other publisher categories were roughly of equal size: scholarly societies (22%, 128 journals), professional publishing organisations (19%, 114 journals), and government agencies (18%, 109 journals). One publisher, Science Press (105 journals), a leading STM publisher in China, dominated in the professional publishing organisation category.

4.3. Subject Fields

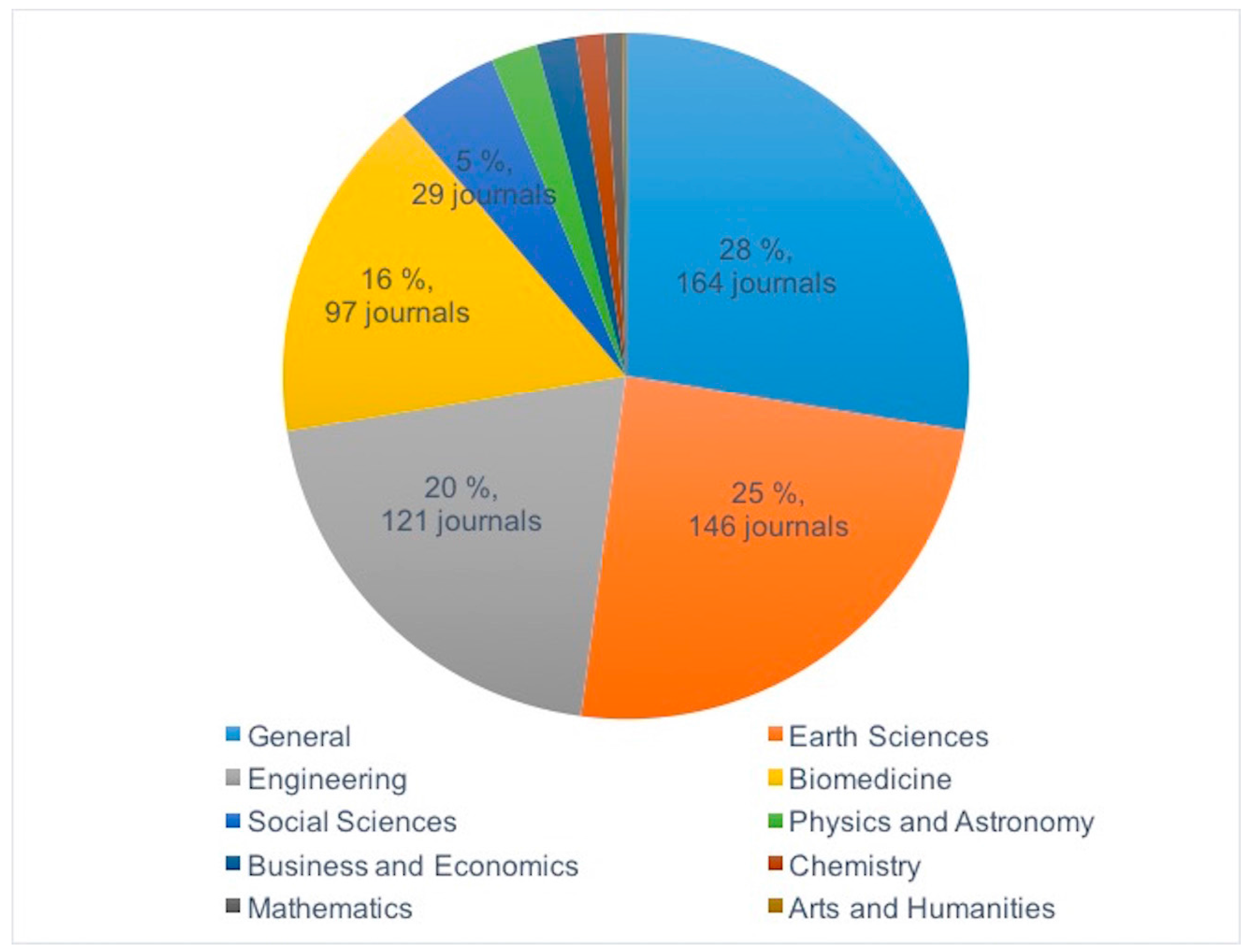

Figure 2 describes the distribution of the journals over subject fields. Journals categorised as “general” were the largest group, with a total of 164 journals (28%). The second-largest category was earth science journals (25%, 146 journals) followed by engineering journals (20%, 121 journals). Biomedical journals ranked fourth in the quantity (16%, 97 journals). The results indicate a highly skewed distribution of Chinese-language OA journals towards the STEM fields.

With regards to the subject field distribution across different publisher categories,

Table 2 shows that about 40% of university OA journals were classified as “general”, which was the largest subject category. More than half of scholarly society journals were in the fields of biomedicine (28%) and engineering (27%). This was also true of journals published by other organisations, in which biomedicine (44%) and engineering (31%) were also dominant. Professional publishing and government agency journals presented similar distributions, both of which had the largest share of journals in earth science.

4.4. Journal Age

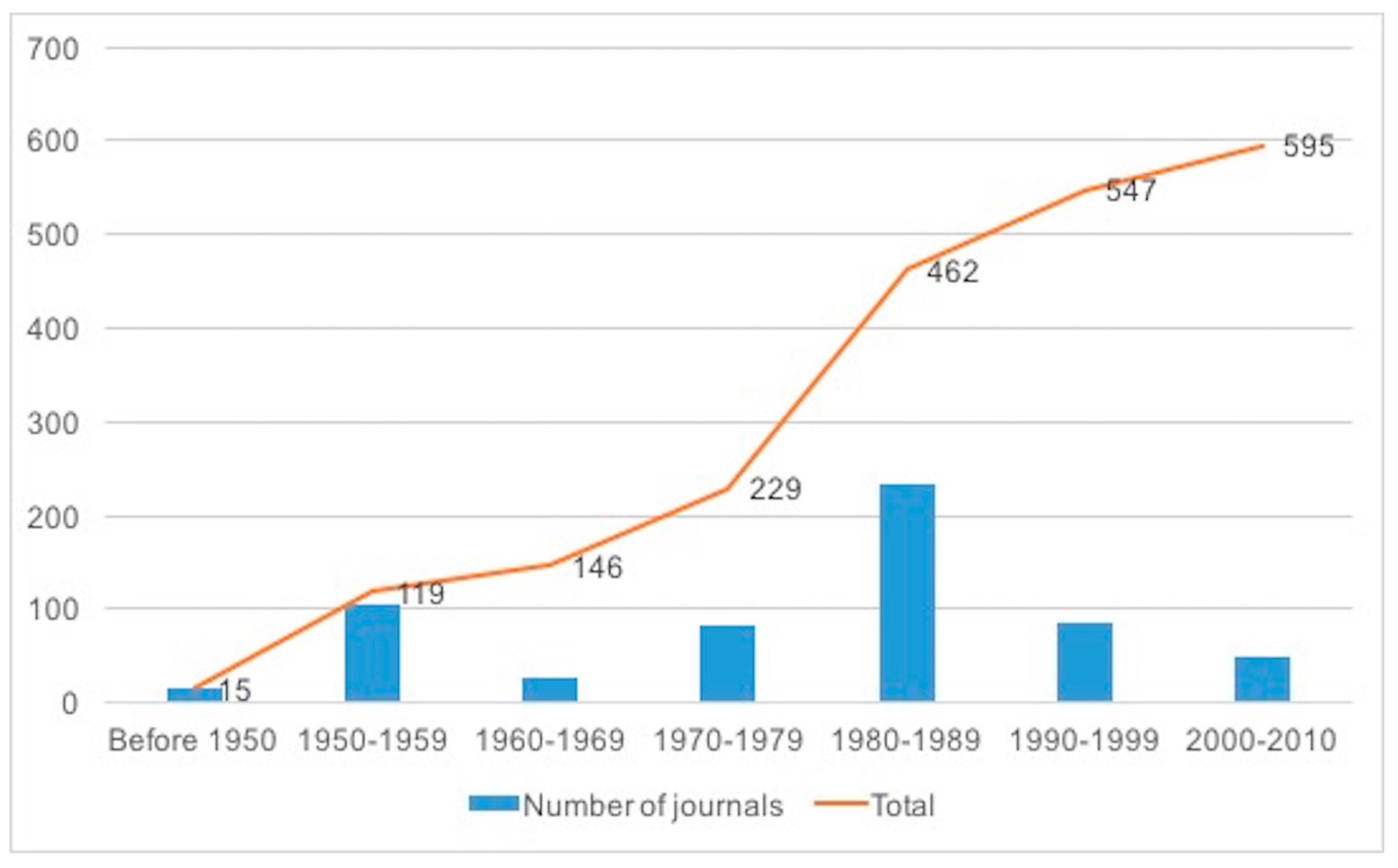

Figure 3 presents the distribution of the journals by the year they were founded. The largest group consisted of journals launched between 1980 and 1989 (40%), with the 1950s being the second most popular start period (17%). Very few journals have been established from 1990 onwards, after the emergence of the World Wide Web, (8%).

4.5. Motivations for Adopting an OA Approach

All the participants in the interviews were asked about the key motivation for their journals becoming OA. In more than half of cases the reason was a belief that OA helps to improve the impact of the journal, whether it was converted to or founded as OA. The participants felt that wider readership, quicker dissemination and additional citation advantages would increase the academic impact. One of the participants particularly noted that authors’ decisions about where to submit depended on a journal’s academic impact (i.e., Journal Citation Report (JCR) impact factor), and that OA could be a means for making the journal more competitive.

Participant 7 argued that OA could provide an additional source of income to compensate for the reduction in subscription income resulting from a decrease in demand for printed journal copies. Participants 2 and 4 felt that Chinese scholarly journals had a moral obligation to communicate academic research findings to the general public. OA publishing was precisely the sort of a model that they needed in order to achieve this aim.

4.6. Barriers for Successfully Publishing OA journals in the Chinese Language

Relating to this, the lack of a sufficient number of high-quality submissions was recognised as a major barrier by most participants. Three participants criticised the national research evaluation system with its strong favour towards publication in the international journals indexed by SCI and EI which has led Chinese journals to suffer from a great loss of excellent papers written by the country’s scholars.

Surprisingly, only two participants noted that the language used in their journals was a barrier, because it restricted submissions from non-Chinese speaking researchers and narrowed the journal’s readership. Participant 1 felt that international readers could understand articles in Chinese provided that there were good English summaries given by journals, but for articles in arts and humanities that method might not be applicable. Chinese poetry, for instance, was much harder to translate accurately into English. Participants 2, 6, 7 and 8 also reported some specific problems with their respective journals, including the lack of clear positioning, long-term sustainable business models, and adequate publishing service abilities.

4.7. Attitudes and Barriers to Converting to English or Bilingual OA Journals

All the participants were asked about their attitudes towards converting their journals into English or bilingual ones and what they felt would be the main barriers in such a transition. The majority of participants were interested in such a change, while three participants were not. One of these emphasized the importance of maintaining an OA journal in the local language in order to target the domestic market only.

The most common barriers mentioned to a change of the language were cost issues. This seems primarily because it would require a large financial investment in the initial stage to recruit highly skilled English-speaking editors and reviewers as well as international experts to serve on the journal’s editorial board. Participant 1 also stated that their top-down management style would make it time-consuming to reach a consensus on such a major change. Participant 6 felt that it would take a lot of time to improve the journal’s quality to get wide international recognition.

The lack of a well-established large publishing platform was seen as a problem by three participants. On the one hand, both Participants 1 and 2 called for such a platform with high global visibilities like SpringerLink to promote local journals. Participant 2, on the other hand also pointed out the drawback of self-promotion through a journal’s independent online domain, compared with such a platform. The current situation has led to a relatively low level of content integration containing isolated and small pieces of information, which might cause a problem in attracting a wider audience.

Participants 3 and 7 felt it challenging to attract submissions from abroad. Firstly, due to the wide adoption of journal ranking systems in universities around the world, authors tend to publish English-language articles in predominantly Anglo-American journals which have an overriding presence in these ranking lists. Secondly, they felt that the scope of their journals seemed not to be interesting to international researchers. Two participants worried that this would be likely to narrow the readership. One of them also expressed the concern of losing Chinese readers who are unable to read English.

The competition from existing similar, but more prestigious international academic journals was seen as another barrier. Several participants felt that they were not confident in competing with them. Only one participant expressed doubts concerning copyright and research evaluation issues, specific to bilingual journals. In copyright agreements it was generally not permitted that an article in an English language journal be republished in Chinese in another Chinese-language journal. It was also not yet clear how same publication released in different languages would be assessed in the existing research evaluation system.

5. Discussion

This study showed a dominant position of the Chinese-language OA journals in the current OA publishing market in China. Since there is a lack of reliable studies of the overall number of scholarly journals in China, the Chinese Science &Technology Journal Citation Reports (2016 extended edition) was used to estimate the target population, in which their source journals were included in the Chinese Science and Technology Paper Citation Database (CSTPCD) [

47]. This is the most complete report of Chinese legitimate scholarly journals in the fields of natural sciences and social sciences, which as of 2016 include 7174 titles. On the basis of this, the share of Chinese-language OA journals in the entire Chinese scholarly publishing market was calculated to be about 8%. Compared to an estimated global share of the gold OA market of between 15% and 18% based on Scopus data as of April 2017, the OA journal’s coverage in China remains low [

22]. The international visibility of Chinese-language journals that become OA is still limited, with small shares in DOAJ, ROAD, WoS, and Scopus, all of which are considered as important proxies to make the journals known by a more international audience. This is possibly due to the fact that many OA journals published in Chinese lag in terms of their publishing standards and lack high academic impacts.

The total share of Chinese-language OA journals published by universities and scholarly societies is larger than that of their counterparts indexed in Scopus, while the ratio of professionally published journals was smaller than that of Scopus’s journals [

45]. The application of the approval system would best explain this skewed distribution. In China, scholarly publishing is run as a government-regulated and not fully market-oriented business. The government hence implemented such a system, executed by the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television of the People’s Republic of China, to strictly examine the publisher’s qualifications for publishing journals [

48]. Universities and scholarly societies are regarded as the entities which are better qualified for academic publishing and better able to meet the necessary conditions of running a scholarly journal than publishing companies without affiliations with a university or government agency, in other words, professional publishers. Unlike China, most other countries commonly employ the registration system, which implies the free right to create scholarly journals.

The distribution of Chinese-language OA journals across subject fields is highly skewed towards the STEM fields. Nearly two-thirds of journals are from these fields, while less than 10% of journals were from social sciences, arts and humanities, and business and economics. The difference between the proportion of STEM journals and journals in other fields is 40%, much greater than that in the complete Chinese scholarly journal landscape (2016, Chinese S & T Journal Citation Reports, extended edition) [

47]. Compared to the OA situation in Latin America, where there is a high adoption rate of OA in their journals published in local languages, the results show that there is a more balanced distribution across different subject fields [

13].

The major reasons for a skewed distribution to STEM fields in the Chinese-language OA market could be attributed to a combination of factors. First, the gold OA model is traditionally more established in the science, technology and medicine (STM) fields than in the humanities and social sciences (HSS). OA journals from these disciplines are far more common. Chinese STEM journals are thus more open and willing to adapt in order to succeed in the changing global publishing environment by adopting OA. Moreover, monographs are the dominant publication form for academics in the HSS fields, which means fewer OA journals are needed. Compared with HSS journals, Chinese STEM journals receive much more financial support. Various programmes are also being implemented by the Chinese government dedicated to funding the development of China’s STEM journals. The “high quality scientific journals” project organised by the China Association for Science and Technology (CAST) since 2006 is a good example; about 150 STEM journals were funded with over CNY 30 million within the first two years [

49]. Another major reason might be that a large part of Chinese journals in the HSS fields offer OA indirectly through the more cost-effective NSSD rather than through their independent online domains, the approach of which falls outside the traditional definition of gold OA [

43].

Journals which cover a broad multidisciplinary field represent the most common form in China’s scholarly publishing system, which is particularly obvious in the example of university journals. In the Chinese language OA publishing market, university publishers continue to have the largest number of these journals. One possible explanation for this finding is that in China such journals have the primary goal of serving the faculty staff as well as postgraduate and doctoral students from almost a range of different research fields in their parent universities by showcasing their work. Compared to other highly subject-specific journals, these journals generally do not have clear disciplinarily boundaries. It is then difficult to attract readers who want to identify research in one area of interest [

48]. Moreover, the names of these journals, especially university journals, are often directly and strongly associated with their sponsoring institutions. This possibly makes authors from outside hesitant to contribute because these journals appear to be mainly intended for researchers at the same institute [

50]. Therefore, the effectiveness of employing an OA model for such journals remains a question unless their inherent disadvantages could be overcome.

The distribution of journals by year of launch follows the developmental trajectory of China’s society. Since the beginning of China’s centralized command economy era in the 1950s, the Chinese scholarly publishing industry started to resume and re-establish in order to develop and fulfil the needs of socialist scientific, educational and cultural undertakings. As a result, a relatively high number of Chinese-language scholarly journals was founded during that decade. In the period 1960–1969, China was in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, causing the destruction of the Chinese scholarly publishing industry. After 1978, with the national economic reformation and opening-up of policies, the increasing social demands led to a boom in China’s scientific research and promoted the growth of Chinese scholarly journals again. The number of newly established Chinese-language scholarly journals then reached their peak. In summary, about 80% of journals emerged before the arrival of the Internet, which implies that most of the current Chinese-language journals were started as printed subscription journals that then converted to digital and OA. This is apparently different from Western scholarly journals published by commercial publishers, mostly operating an OA business model from the outset. However, many journals published by university and scholarly society publishers have chosen to become OA in a similar fashion as in China [

45].

Increased academic impact is the most anticipated benefit by the participating Chinese scholarly OA publishers in this study. This is probably closely related to the widespread economic model of most Chinese scholarly journals, which are largely subsidized by national or provincial governments directly or indirectly through, for example, scholarly societies, academies and institutions [

24]. Even though some of them continue to charge subscription and publication fees as other sources of revenues, relying solely upon them is much riskier for sustaining both the actual production of the journals and the operations of the editorial office. On the one hand, many Chinese scholarly journals have small distribution quantities of print copies every year, thereby largely influencing their incomes from this part [

51]. On the other hand, three giant Chinese aggregators, including the CNKI database [

52], Wanfang [

53], and Chongqing Vip [

54], play a major role in helping China’s scholarly publishers provide end users with the e-content of published journals because they are granted non-exclusive or exclusive distribution rights by the publishers. The Chinese scholarly resource is then being monopolized by these third-party aggregators, through which they have made the largest financial gains while providing very little compensation to scholarly publishers [

48]. Due to their wide coverage of almost all full-text scholarly journals, well-developed digital infrastructure, and professional customized services, subscription through scholarly publishers becomes less attractive to both individual and institutional users when they consider purchasing the online content. It could thus be estimated that the subscription revenue for Chinese scholarly journals per year is not comparable to the situation of Western commercial publishers where their high profit margins come from. The OA publishing model might further manifest a negative influence on the journal’s subscription income. Moreover, charging publication fees existed long before the arrival of the author-pays OA model in China. In 1987, an experiment with publication fees started, permitted by the Chinese government but not recommended. Up to 2006, more than ten government ministries and the provincial journal management divisions issued documents of concern, and controversy remains regarding the rationality of such charges [

51]. In this model, charging authors by the length of articles is the primary pricing principle of most Chinese scholarly publishers. There are clearly variations between different journals in terms of the fees charged largely due to a lack of unified standard in implementing the publication fees at the national level. From the interviews, the average publication fees of these journals is considerably cheaper than the global average article processing charges (APCs) at around USD 900, and some of them are much below the average cost of publication [

55].

However, the eligibility for government subsidies is essentially determined by the impact of the scholarly journal, primarily measured by impact factor and other citation data provided in the Chinese Science Citation Database–Journal Citation Report (CSCD–JCR) Annual Report [

56,

57]. Low-impact journals are less likely to receive the financial support from the government and invest in their own development. As a result, financial restrictions make it difficult for them to bolster the impacts and can even lead to a survival crisis, resulting in a vicious circle.

The lack of sufficient numbers of high quality papers with respect to important scientific research achievements is perceived as the biggest obstacle to successful publishing of journals by the participating Chinese OA publishers. There also have been several studies reporting the scale of this problem. Dong estimated that at least 135,598 papers written by Chinese-speaking scholars were published in international journals in 2011, based on the data from Science Citation Index Expanded Database [

58]. Wu et al. analysed the extent to which Chinese science and technology papers outflowed from China to abroad between 1992 and 2011, and found that the annual outflow rate has continued to increase over the past two decades, reaching 67.1% by 2011 [

59].

The papers outflow might be the negative effect as a result of the existing academic assessment systems at both the institutional and national levels [

4]. Adopting the number of publications in SCI and EI-indexed journals or their equivalents as key indicators of a university or an institution’s academic level by major national research funders has made Chinese institutions incentivize their researchers with monetary rewards to publish more papers in such journals. Worse still, career promotion, project funding, and obtaining academic degrees are all determined on this basis [

58]. However, international indexing systems such as SCI favour English-language journals based in English-speaking countries, such as the UK and the USA [

60]. Because the scientific quality of papers in Chinese-language journals in general is quite low, they have little chance of being indexed. It is therefore natural that Chinese researchers choose foreign journals with high impacts. A rapid expansion of Chinese research publications, in particular, publicly-funded papers in English published in SCI source journals has been witnessed in the last decade [

58]. Broadly speaking, China’s method of academic evaluation is highly influenced by a reliance on the pervasive concept of “academic excellence” used to identify the best researchers and institutes in all regions of the world. This is nevertheless criticized and questioned with respect to actual efficiency and reliability [

3,

61].

Surprisingly, although language is confirmed to be the main factor that limits the international communication of journals published in Chinese [

62], language is not acknowledged by most OA publishers participating in the interviews as a major barrier. The primary reason for this situation is that they have developed various strategies to deal with language issues, including providing detailed English summaries of published Chinese articles, translating a selection of good Chinese papers into English and promoting them through domestic recognized full-text databases such as Wanfang and CNKI, and even setting up a “twin” English journal.

There remains some interest among the participating OA publishers in converting their journals to publish in English directly. However, a major concern over cost issues, especially regarding financial resources, hinders these interested publishers in internationalising their journals. Economic instability puts Chinese-language OA journals at risk, since it affects long-term financial viability. This points to the importance of the need for finding a long-term sustainable solution that is suitable for the Chinese context in an OA environment. The APC-based model is currently a major funding method for full OA journals, but a pure APC model may not be applicable in the Chinese context. There is a correlation between APC price and quality in terms of citation rates. Authors are thereby more likely to select OA journals that can offer a better quality level with respect to what they have paid [

63]. Since Chinese-language OA journals continue to have a relatively low impact, the increase in the amount of publication fees that suffices for covering the total cost of publishing may intensify the pressure to attract Chinese authors. Hence, the setting of publication fees must be reasonable and take into account costs, quality, author’s ability to pay, and disciplines.

A complete subsidy model from a government source can offer one solution to this problem, but this can be a slow process due to a lack of governmental strategies for gold OA in China. Alternative models, for example, the library partnership subsidy model created by the Open Library of Humanities (OLH) might be seen as another potential solution, as the Chinese library community is the strongest supporter of the OA movement [

31]. In this model, libraries play a more important role than just a sponsor, as they are also involved in some management processes [

64]. The author believes that this will form a much firmer basis for long-term cooperation, enabling publishers to achieve more sustainable financing. In addition, building China’s OA publishing portal appears to be one good alternative that can help to address this challenge. This portal can partly replace commercial aggregators to provide Chinese-language OA publishers with digitization and dissemination functions at a low or even no cost by means of government funding. Some open source software solutions, in particular Open Journal Systems (OJS), can play a crucial role in terms of its technical infrastructure [

65]. Furthermore, it is worth pointing out that authors’ source of funding to pay publication fees varies across different disciplines. In comparison to STM disciplines, HSS scholars are granted much fewer funding opportunities [

66]. Because of this, Chinese authors from HSS fields are more reluctant to accept the author-pays model [

67]. Thus for Chinese-language OA publishers in these disciplines, sufficient governmental commitments are needed to financially support them to survive and develop. Other obstacles identified in the interview, including the fear of competition, the lack of confidence in self-promotion and the difficulty of attracting submissions, shed light on the lack of competitiveness of these journals published in the Chinese language.