Abstract

Appropriation is a common practice in art and literature; electronic literature in particular lends itself readily to appropriation and collaboration, due to its multimodal and born-digital nature. This paper presents practice-based research examining the effects of digital appropriation on two works of digital fiction (a hyperfiction and an interactive fiction), demonstrating how it alters the creative writer’s typical process, as well as the resulting narrative itself. This practice of appropriation results in “implicit collaboration” between the digital creative writer and those whose work is appropriated, an arguable form of shared authorship. Questions regarding the ethics of this practice, including copyright concerns and authorship, are discussed.

1. Introduction

Appropriation is a readily acknowledged practice in the arts, particularly the visual arts, where it contributes to continued discourse and response; as Voyce notes, “(t)he history of the twentieth- and twenty-first-century avant-garde is a history of plundering, transforming, excavating, cataloguing, splicing, and sharing the creative output of others” [1] (p. 408). In literature, appropriation is frequently a gray area between inspiration and plagiarism; electronic literature, however, with its frequent merging of the visual and literary arts (among others), its engagement in the free-sharing culture of the internet, and its use of easily duplicated and re-applied digital resources, lends itself more readily toward collaboration and appropriation. As I have found in my own work, and this paper will show, appropriation alters both the writer’s process and the final narrative, resulting in an implicit collaboration between writer/artist and those whose work is appropriated.

I use the term “implicit collaboration” here, as opposed to the more familiar appropriation, for several reasons. Appropriation is a recognized practice in most media, perhaps most used in visual arts, but certainly utilized in film and literature [2,3]. Barefoot refers to Joseph Cornell’s appropriation of found footage as “recycling”, which at the very least puts a positive spin on the process, that of making use of materials which would otherwise be thrown away. Ken Goldsmith echoes Foucault, Barthes, Genette, and Benjamin in asking “...isn’t all cultural material shared, with new works built upon preexisting ones, whether acknowledged or not?...What is the difference between appropriation and collage?” [3] (p. 110), while espousing the benefits of “uncreative writing” in terms of artistic inspiration and discourse.

The term appropriation, however, along with other terms such as assemblage, remix, sample, and collage, fails to connote the authorship of the “sampled” artists whose work is incorporated. Other, more negative terms, such as plagiarism or Jenkins’s “textual poachers” [4], have clear connotations of unethical, even illegal, actions. Artists refer to their intertextual processes using various more innocuous terms: Mark Amerika’s “surf-sample-manipulate” [5], for example, is grounded in the actual activity of seeking material, appropriating elements of found art, and re-purposing it to create new art. Ken Goldsmith’s description of what he terms “uncreative writing” is almost self-effacing, and in fact ironic given that he describes his process of using only found material in his writing as having “as many decisions, moral quandaries, linguistic preferences, and philosophical dilemmas as there are in an original or collaged work” [3] (p. 119). Spinuzzi’s “compound mediation” is nearly mechanical, describing a process of “bring[ing] together texts from multiple sources...in order to create new texts, a process often involving breakdown, reallocation of resources, creation of new hybrid genres, and shifts in power” [6] (p. 382) which removes the authors of these texts almost entirely.

My purpose in choosing the term “implicit collaboration” is to acknowledge both this active process of appropriation, but also the inspirational effects of collaborating with other artists, both within and without the genre in which I am actively working. The appropriated works (I should say “consciously appropriated”, to differentiate them from Genette’s cultural and literary palimpsests [7]) are works that have been placed in the commons for the express purposes of such appropriation. The use of Creative Commons or similar licensing denotes an attitude of sharing and co-creation, which “serves to broaden the consumption of (creative) commodities through space and time, cementing their position in popular culture” [8] (p. 468). As the majority of works with such licenses carry an “attribution” caveat (works can be used and re-distributed only if proper attribution is given), it is clear that the creators want their contributions to be acknowledged, their authorship explicitly recognized. This “giving away” of resources (though in a digital environment, resources are duplicated, never lost) in a digital gift economy results in increased capital in the form of status [8,9].

Implicit collaboration occurs in overlapping spaces of Internet gift economies: exhibition space and collaborative space. Currah identifies the first as a space for user-generated content on display (YouTube, Flickr), and the second as group production projects such as Wikipedia and Source Forge [8] (p. 478). By sampling works offered in exhibition spaces, recombining them and offering them up to further derivatives, a creative, collaborative gift economy is created. With it, questions and concerns arise with regard to attribution, copyright, monetarization, and the increasingly nebulous notion of authorship.

Of course, these collaborations are not as explicit as a demarcation of co-authorship would denote. As I explore in this paper, the creation of these “compound mediations” [6] involves surfing for materials, sampling elements that inform or inspire my work, and manipulating them for incorporation into a new piece. It could be argued that this is no more a collaborative process than that of workers on an assembly line: workers farther down the line may have to adjust their activities according to deviations committed by previous workers, but overall the process is not an equally partnered activity. As I will show, however, found art and subsequent appropriation of that art in a new work have the potential for profound influence. The inclusion of found art and that inclusion’s effect upon the creative process combine in a collaboration between artists, made implicit because the original artists have no explicit authorship role in the creation of the new piece.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper is the result of practice-based research into the effects of digital composition on the writer’s practice and the final narrative structures, a creative experiment designed to answer questions about the process and results of the practice itself: “it involves the identification of research questions and problems, but the research methods, contexts and outputs then involve a significant focus on creative practice” [10] (p. 48). While composition research is often designed to expose cognitive writing processes to observing researchers, it is difficult to make internal, often subconscious, creative decisions explicit for the purposes of studying how writers write. Unlike post-textual analysis, in practice-based research, the practitioner-researcher is able to examine these usually implicit and unreported processes, making them explicit; these insights can then be further expanded into further practice-based research, or used as the foundation for ethnographic composition studies of artists at work.

Graeme Sullivan outlines several types of practice-based research, depending on the specific area of interest and effect, including theoretical, dialectical, conceptual, and contextual [10]. The research presented here aligns foremost with the conceptual framework of practice-based research, in that the creative undertaking is an attempt to understand the artefacts themselves. The digital fictions discussed in this paper were conceived and composed for the express research purpose of answering questions about the effects of digital composition on practice and narrative. As such, I engaged in ethnomethodological [11,12] observation of my writing activities, maintaining notes, journal entries, comments on drafts, and other relevant, observable paratexts to the composition, in order to “make continual sense to (myself) of what (I was) doing” [12] (p. 324). I was then able to interpret these notes and paratexts, placing them within the context of composition cognition [13], and to conduct post-textual, media-specific analysis [14] of the narratives that resulted. In this manner, the various strengths of practice-based research, ethnomethodology, cognitive process, and post-textual analysis are combined into a robust method of evaluating the activities of the practitioner/researcher, and the resulting discussion is presented here. (The details of my particular method are more thoroughly outlined elsewhere [15,16].

A key component in practice-based research is the aspect of serendipity as defined by Makri and Blandford [17,18]: “a process of making a mental connection that has the potential to lead to a valuable outcome, projecting the value of the outcome and taking actions to exploit the connection, leading to a valuable outcome” [18] (p. 2, emphasis original). For any researcher, serendipity is likely to occur during the research process, as the confluence of this newly generated data and the expertise required to recognize its significance is the crux of knowledge generation. The notion of serendipity can be applied to artists at work to better understand how ideas are generated, new genres are created, plot twists are incorporated, language is defamiliarized, and more. By its very nature, serendipity cannot be accounted for in the design of practice-based research; nonetheless it plays a key role in aiding the practitioner-researcher to recognize significant activities, particularly cognitive activities that are not otherwise obvious to external observers, as it did in the research described in this paper. The central question of this research project was to examine the process of digital writing; appropriation was not initially considered as an area of interest, yet the creative process yielded significant serendipitous insights.

The purpose of the overarching research project was to offer insight into the creative practice of writing fiction for digital media. As a published fiction author, I had an established prose writing practice; as a researcher, I was interested in how changing this established practice from prose to digital fiction would affect my creative process and the narratives that emerged. Using the methods described above, I designed a creative experiment: to write a narrative realised in both prose and digital forms. As I wrote the narrative, I maintained documentation of the process in the form of drafts, source code, revision notes, and in situ observations of the work-in-progress. Once the creative project was completed, I was able to apply media-specific post-textual analysis to the narrative artefacts (a prose novella and a digital novel), and ethnomethodological analysis of the notes created during the project. The digital novel, Færwhile: A Journey through a Space of Time, is available at [19]. The results of the analysis as pertain to the more specific research question of how digital appropriation affects the author and narrative are presented here.

3. Results

The following sections will examine two of my creative texts, “Awake the Mighty Dread” (interactive fiction) [20] and “Streams Slipping in the Dark” (hyperfiction) [21], presenting an insight into their composition through the use of implicit collaboration with other artists, as well as analysis of the narrative effects of these “found” resources on the final artifacts.

3.1. Process and Narrative Effects

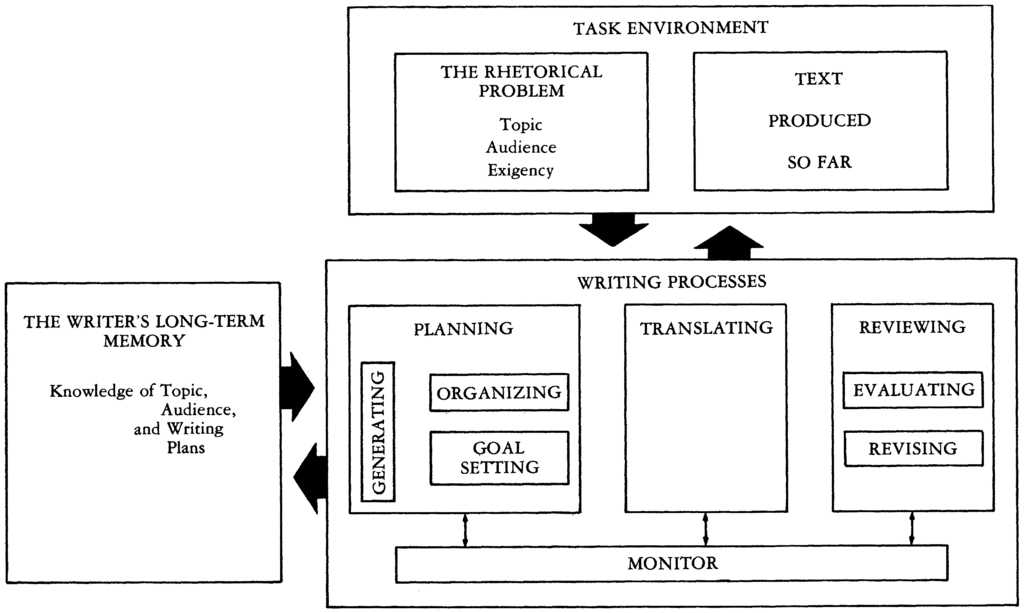

“Awake the Mighty Dread” and “Streams Slipping in the Dark” are pieces written as part of a larger work; the project as a whole is an examination of multimodal creativity. In order to map out the chaos that is so often a writer‘s process, I begin with Flower and Hayes’ 1981 composition model [13] (shown in Figure 1). This hierarchical model acknowledges the fluid (and often chaotic) mental processes of writing, as it accounts for the author/creator‘s shifts in, out, and through planning, writing, and rewriting phases at any given point in the process.

Figure 1.

Flower and Hayes’ Cognitive Process Model (“A Cognitive Process Theory” p. 370) (used with permission).

The model is not a perfect one, as it is so self-contained to the particular text currently underway, and does not account for external influences such as interruptions, long-term breaks in the creation process, or simultaneous work on other texts. It is also notable that this cognitive process model does not in the first instance incorporate multimodal forms of creation, focusing exclusively on written composition. It may seem inappropriate to apply this model to the synaesthetic process of creating digital fiction in what Andy Campbell calls a “liquid canvas” [22], but incorporating Flower and Hayes’ 1984 Multiple Representation Thesis [23] offers a more fluid aspect. This thesis poses that “(w)riters at work represent their current meaning to themselves in a variety of symbolic ways”, which includes multiple modes such as imagery, prose, sound, movement, as well as rhetorical devices such as metaphor, schemas, and abstractions [23] (p. 129). Expanding the model to include not just written prose but all modes within the current text permits examination of a multimodal creative process.

For the purposes of this paper, I am primarily interested in the white-space between planning and translation. This gap is where implicit collaboration has a role, as it is where “surfing” for materials enters the process. During the planning process, I envision the text; this generally involves drafting print-only versions of the text, storyboarding, and concept mapping, though not necessarily all of these stages occur for every project. For multimodal projects, another box could be added in this white space: seeking resources (Amerika’s “sampling” [5]). As the following sections on use of images and use of source code explore, explicitly exposing myself to and actively seeking others” art to appropriate during this point in the process has a direct effect on the translation of the project at hand.

3.1.1. Use of Found Images in Hyperfiction

“Streams Slipping in the Dark” [21] is a hyperfiction created through the use of html and Javascript. The story follows several characters as they make their separate ways through a fairyland in search of one another, converging upon a castle and its resident queen. The piece was first drafted in print form, with the digital hyperfiction in planning stages as the print text was composed. Planning for the hyperfiction consisted primarily of hand-drawn storyboards and concept mapping of the navigation. Once the storyboards and navigational maps were complete, I began the search through Creative Commons sources (flickr.com, deviantart.com, Google Image search) to find images and audio files to sample, manipulate, and appropriate.

The working plan at this stage was to build the hyperfiction around the visual concept of a Tolkienesque fantasy map of the island queendom that the characters were exploring (see [24] for an example). I made extensive use of stock materials on deviantart.com for parchment-like background textures and Photoshop brush sets of map icons (mountains, villages, trees, etc.), which I intended to assemble into a final image of my own creation. The hyperfiction’s rhetorical goal was to offer an interactive map that would deliver bits of the story in chunked lexias as the reader explored, inviting the reader to follow the actions of the characters within the story.

I am not a visual artist in any way; even armed with the ingredients for a fantasy-style map, I still needed some visual samples of finished maps to guide me. In my quest for more experienced artists’ creations on deviantart.com, I discovered deviantart.com user anna-terrible’s 2011 ink-and-watercolor “childhood dreamspace map” (see [25]). deviantart.com (at this time) does not offer a search filter for work with Creative Commons licensing, and thus searches result in a mix of works that are and are not available for appropriation. At times, this can be frustrating, as I generally find that the highest quality work—i.e., that which I’d be most inclined to use - carries full copyright protections. Often these form part of professional artists’ sample portfolios. On the other hand, the inability to filter this protected, professional-level work out can, as in this case, lead to inspiration rather than full appropriation. In this case, anna-terrible’s image is not shared in the commons, but its whimsy, color, and depth were eye-catching and intriguing, lending the image toward narrative rather than mere illustration; the colors and textures overcame the barrier of the screen to create “a stage on which fairy tales spring to life” [26] (p. 435). The artist’s description furthers this perception: “for class i had to draw a map of any events that happened during my childhood. this is where i remember dreaming as a kid (sic)” [25] (n.p.). The inspiration for “childhood dreamspace map” seated itself well in the narrative of “Streams Slipping in the Dark”, which centers on a young girl who is, in essence, dreaming the entire landscape(s) in which the story takes place.

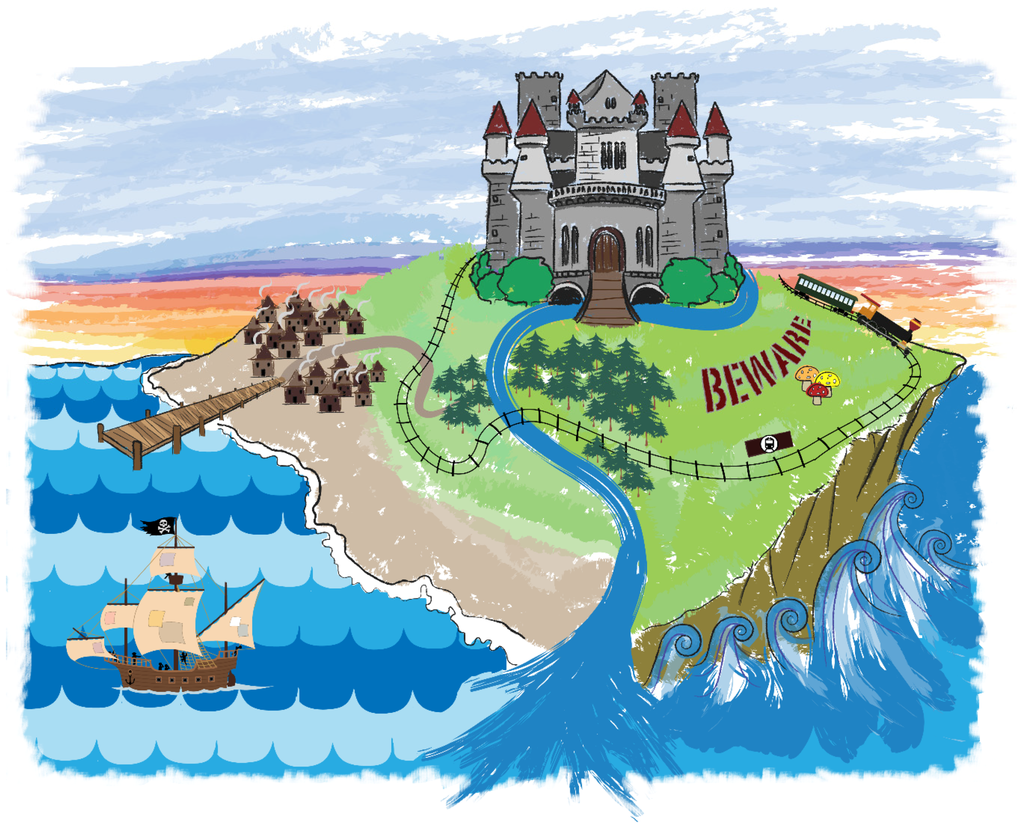

Finding this image first resulted in exaltation, as it seemed to be an image I would have created for this piece had I the requisite skillset, followed swiftly by extreme disappointment that it was not licensed for commons use. I repeatedly returned to the image, however; it did not fit into the story perfectly, of course. “Streams” was centered on a castle, and contained neither a haunted house nor a marketplace, which are the defining features of “childhood dreamspace map”. Eventually, I settled upon a new plan, adjusting the previous rhetorical goal: to use desktop illustration to emulate the outline, depth, and feel of anna-terrible’s dreamspace for a visual space that invited the reader to explore, while manipulating the image to fit more seamlessly into the narrative I had created. The result clearly shows the origins of the image as belonging to anna-terrible, but sufficient changes wrought to bind it within the storyworld of “Streams Slipping in the Dark” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interactive Image from “Streams Slipping in the Dark”.

In the end, the translation of this hyperfiction was a much more ground-up creative activity than I had planned for. After all, my initial work was largely a process of assemblage: using other artists’ Photoshop Brushpacks and textures to piece together a useable fantasy map. Inspired by anna-terrible’s dreamscape, however, I embarked upon a piecemeal illustration journey that resulted in appropriation (the basic outline of the island, the pirate ship, the train, and the basic outline of the castle all came from other artists), assemblage (putting all the pieces together, manipulating them to work together in the same image), and original creation (the village, the forest, the water, the coloration).

Anna-terrible’s dreamscape also affected the narrative and the (implied) readers’ experience. Had I carried out my original plan, the resulting image would have carried connotations of Tolkien-variety fantasy, familiar and even clichéd. It would have incorporated iconic imagery (representations of mountain ranges, forests, cities, etc.) in a largely muted color palette (that of parchment-and-ink), with a two-dimensional aspect. The final image that I created (Figure 2) instead carries a more whimsical, child-like tone, calling to mind pop-up storybooks in its depth and color, immersing the reader in the fairy tale world through Benjamin’s “primal phenomenon” of color [26] (p. 442). It carries forth the fairy-tale aspect of the narrative through to the imagery, and illustrates (though not explicitly) the truth underlying the narrative itself: that the world is created in the dreaming mind of a child. The effects of illustration and depth, instead of flat, representative map-space, invite the reader to explore the map. They offer a space within which the reader can travel him/herself, rather than merely following a dotted line of the characters’ travels. The further the reader moves into the image, the more narrative they discover, moving with the characters rather than observing from a distance.

The implicit collaboration with anna-terrible in this piece resulted in better integration of the modes used within the text than my original model and storyboards had outlined, better meeting the rhetorical goal I had established for the piece. In the next section, I will explore a more direct form of implicit collaboration: code-borrowing.

3.1.2. Use of Open-Source Code in Interactive Fiction

The philosophy of open-source code sharing that I will use in this paper is largely attributed [1,27] to Richard Stallman’s contributions to the GNU project and his group’s “free software definition” [28], though they are careful to differentiate between “free” and “open source”. The driving motivation between an open or free sharing of software code for noncommercial purposes is to encourage innovation and collaboration [1]. The benefit to artists participating in this open network of dissemination is a “proliferation of potential texts amid continuously changing assemblages of authorial, intertextual, and communal networks” [1] (p. 409).

Many digital writers and poets are not code writers when they begin working in digital media. While I had done some rudimentary HTML coding in the 90s, and had picked up a little basic programming here and there in school, I was not proficient in any programming language when I began creating digital fiction. At this stage, I conduct most of my programming work through the “cut-n-paste” method: determining what function I need, searching for the code online, cutting and pasting it into my own work, and adjusting from there. I am not alone in this practice, as evidenced by the hundreds of Javascript cut-n-paste code repositories online (such as those listed at [29]).

The first code-based writing that I attempted was prompted by a university module I audited in writing games, using the Inform7 platform for interactive fiction (IF). Inform7’s source code is a friendly language to learn for newcomers, as it is actually structured to mimic the English language as much as possible. For instance, the line “A chest is an unopened, openable container in the dungeon” defines an object (the chest), its properties (it is a container that is currently closed, but capable of being opened), and its particular location (the room labeled “dungeon”). In addition to the (initially) straightforward structure of the source code, Inform7 has a small but enthusiastic community online, and many who work with the program write and share extensions to the program as well as the source code for their own IFs.

In crafting my first IF, I made use of many of these extensions; I also relied heavily upon Aaron Reed’s Creating Interactive Fiction with Inform7 [30]. Reed frequently uses examples from his 2010 IF Sand-dancer [31], and offers links to downloadable source files from that work. Rather fortuitously for my own work, Reed’s Sand-dancer incorporated a trickster figure, as mine did, and revolved around similar recurring themes of dream and memory. It seemed a custom-made guide for crafting my tale, the rhetorical goal of which was to immerse the reader into the storyworld through a highly interactive narrative that placed the reader into the main character’s second-person perspective, thus intimately following both her interior and exterior journey.

The most prominent of the borrowed elements from Reed’s IF were those defining memories, and actions concerning memories; my text converted these to dreams. In Sand-dancer, memories are things in a container labeled “subconscious”. They are triggered by the player-character (PC) handling particular objects within the world of the story, labeled “charged objects”. The first few lines of Reed’s code defining memories are as follows:

- A memory is a kind of thing. A memory can be retrieved or buried. A memory is usually buried.

- Suggestion relates various things to one memory (called the suggested memory).

- The verb to suggest (he suggests, they suggest, he suggested, it is suggested, he is suggesting) implies the suggestion relation.

- Understand “memory/memories” as a memory.

- Does the player mean doing something to a memory: it is unlikely.

- The subconscious is a container. When play begins: now every memory is in the subconscious.

- Definition: a thing is charged if it suggests a memory which is in the subconscious.

In my IF, “Awake the Mighty Dread”, I used this example to generate a set of dreams that the PC falls into when they touch charged objects or enter the command “sleep” (differences from Reed’s code are underlined):

- A dream is a kind of thing. A dream can be dreamed, or undreamed. A dream is usually undreamed.

- Trigger relates various things to one dream (called the triggered dream).

- The verb to trigger (he triggers, they trigger, he triggered, it is triggered, he is triggering) implies the trigger relation.

- Understand “dream/dreams” as a dream.

- Instead of examining a dream when player is awake: say “Dreams only become real when you’re asleep”.

- Does the player mean doing something to a dream: it is unlikely.

- The subconscious is a container. When play begins: now every dream is in the subconscious.

- Definition: a thing is charged if it triggers a dream which is in the subconscious.

Clearly, the code is copied and pasted from Reed’s source code, with some (but not all) labels changed to suit the new story: “memories” become “dreams”; “suggest” becomes “trigger”. The code shifts significantly after this sequence, as the action of dreaming required further parameters related to sleeping and waking that were not required for Sand-dancer’s use of memories.

Use of Reed’s code did not introduce dreams to the overall narrative, as dream sequences are clearly present in drafts of “Awake’s” analogue version, though they are triggered not by charged objects or conscious efforts to sleep but by extreme emotional stress. The effect of the code-borrowing in the IF is significant to the finalized text, however, as it did result in a shift in the action of the IF narrative through the addition of charged objects. The PC must make their way through a large palace full of objects – some charged, some not – in order to reach the conclusion. Falling into dreams offers crucial insight into the story, why it is happening, what the PC has to overcome; falling into dreams and not being able to escape them leads to a bad end for the PC (death or inability to continue with the story). These charged objects triggering these dreams over and over are not present in early drafts of the story, as the analogue story follows the path I as the author dictated. Their appropriation from Reed’s IF shaped the text’s translation significantly, and allows for “Awake’s” expansion into Montfort’s “potential narratives”, brought about by the exploration of space and objects that is intrinsic to interactive fiction [32] (p. 14).

It is also important to note that I completed one analogue draft of the story before beginning to write the IF source code; Reed’s code served to add functionality and depth to an already-developed narrative and storyworld. Had I begun with his code as inspiration for a new IF of my own, perhaps the work that resulted would have been more derivative than collaborative. As I was working from an established narrative or text-so-far, however, Reed’s appropriated source code expanded my work in ways that, given my novice capability with the code, I could not have anticipated or built without its incorporation. While quite often the cut-n-paste technique leads to changes in the narrative because of limitations (e.g., code has not been previously written/made available for the desired functionality), here it enhanced and pushed “Awake” into narrative possibilities made available only through the implicit collaboration of the more experienced code writer.

4. Conclusions

The ethics of appropriating other artists’ work is, and likely always will be, contested [3,9]. Copyright laws were introduced in part to reduce exploitation from appropriation, and to provide a stable balance between excessive control of content that under-utilizes creative works and free sharing that results in under-production [8] (p. 468). These laws have endured numerous revisions since their inception in attempts to maintain this balance, and digital technologies have set the balance swinging yet again, as evidenced in the “push-pull” of anti-theft software designed to protect content and that software explicitly designed to remove such protections [33] (p. 153).

The currently prominent solution, for some, is to offer creative work in the commons under licenses offered by Creative Commons [34]. While these works are of great benefit to artists and writers as demonstrated by my own work in this paper, Currah notes that creation of this open, gift economy can result in several downsides: copyright theft, floods of poor-quality works, malicious attacks, and asymmetric participation in the ability to do more taking than giving. Creative Commons licenses offer mitigation for some of these, as creators can place caveats on the use of their work to account for them, such as attribution to ensure credit and “share-alike” to ensure new works are fed back into the commons. Of course, gray areas still exist: for example, how to credit anna-terrible or Aaron Reed for their inspiration, when their work was not directly and obviously appropriated per Creative Commons licensing? This system rides the fence between a completely free and open gift economy, and one in which authorship (and its implications of ownership and commodification) is explicitly codified.

The need for such a system arises from a creative culture dependent on implicit collaboration, “texts generating other texts in an endless process of recycling, transformation, and transmutation with no clear point of origin” (Stam, in [2] (p. 166)). The issue is not new to digital texts, as implicit collaboration and even outright appropriation has certainly always been a factor in print text as well, necessitating the original copyright laws; where digital media makes the matter more prominent and commonplace is in the ease of copying, duplication, and re-application of digital text and art, and in the internet culture that promotes free sharing and use of resources. A text with no clear point of origin ostensibly has no clear point of authorship. If this is true for adaptations and transtexts, it is certainly true for digital texts, which Cover notes “[blur] the line between author and audience, and erod[e] older technological, policy and conventional models for the ‘control’ of the text, its narrative sequencing and its distribution” [33] (p. 140).

Losing the distinction between author and reader can be viewed quite negatively. German author Helene Hegemann’s 2012 novel Axolotl Roadkill garnered her widespread criticism for what some called plagiarism and she called remixing [35]. Kenneth Goldsmith recalls that some poets’ reactions to their work being appropriated to the Issue 1 poetry anthology as copyright theft, misattribution, and even vandalism [3] (pp. 121–122). Sinnreich, Latonero, and Gluck’s 2009 survey [9] showed that audience attitudes toward appropriation depended upon the perception of commercialism and originality in the piece: if work was appropriated for profit, or if the appropriated work was seen as copying rather than contributing something original, it was more likely to be seen as unethical.

Many, however, view creative works—even their own—as part of the cultural commons. Goldsmith sees “uncreative writing” as a valuable asset to creative writers, enabling inspiration and continued discourse through intertextuality. Younger respondents in Sinnreich, Latonero, and Gluck’s survey “tended to be more aware of configurable technologies and practices, more likely to engage in them, and—most interestingly—more likely to accept the legitimacy of these expressive forms, by viewing remixes and mash-ups as ‘original’” [9] (p. 1249). The inception, growth, and continued use of sharing networks such as Stallman’s GNU and the Creative Commons demonstrates that notions of collaboration and shared work are prominent in digital creative environments. This collaboration and shared work—even if it is asymmetrical—increases the sense of ownership and investment in a text for those who contribute. From fan fiction writers [36] to crowdsourced workers [37], “...many people enter the grey area of configurability as consumers, and... gradually expand the locus of their agency and expertise” as producers, creators, and authors [9] (p. 1249). As this work continues to be cycled through the commons, sampled, manipulated and recycled, it inspires imitation, yes, but also further innovation and creativity.

Part of this cycle of creativity depends on the activity of implicit collaboration. Appropriation is intrinsic in much of the creative activity in the current Internet gift economy; exploring the effects arising from sampled work can expand our understanding of the creative process. The concept of implicit collaboration, like the “attribution” tag offered by Creative Commons licensing, acknowledges the authorial contributions of the sampled artists, as well as the communal nature of artistic exchange. More than discourse, works engaging in this process arise from the specific talents and visions of those whose sampled works inspire, inform, and shape the active work.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Stuart Moulthrop, Astrid Ensslin, and Alice Bell for feedback on a previous version of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Voyce, S. Toward an Open Source Poetics: Appropriation, Collaboration, and the Commons. Criticism 2011, 53, 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barefoot, G. Recycled Images: Rose Hobart, East of Borneo, and The Perils of Pauline. Adaptation 2011, 5, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, K. Uncreative Writing; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Amerika, M. Surf-Sample-Manipulate: Playgiarism on the Net. Telepolis , 1997. Available online: http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/3/3098/1.html(accessed on 13 February 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Eilola, J.; Selber, S.A. Plagiarism, Originality, Assemblage. Comput. Compos. 2007, 24, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genette, G. Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Currah, A. Managing Creativity: The Tensions Between Commodities and Gifts in a Digital Networked Environment. Econ. Soc. 2007, 36, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnreich, A.; Latonero, M.; Gluck, M. Ethics Reconfigured. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2009, 12, 1242–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G. Making Space: The Purpose and Place of Practice-led Research. In Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts; Smith, H., Dean, R.T., Eds.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2009; pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, H. Studies in Ethnomethodology; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, D. The Cognitive as the Social: An Ethnomethodological Approach to Writing Process Research. Writ. Commun. 1992, 9, 315–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, L.; Hayes, J.R. A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. Coll. Compos. Commun. 1981, 32, 365–387. [Google Scholar]

- Hayles, N.K. Writing Machines; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Skains, L. Færwhile & the Multimodal Creative Practice: Composing Fiction from Analogue to Digital. Ph.D. Thesis, Bangor University, Bangor, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Skains, L. Practice-Based Research: A Methodology for Arts Practitioner-Researchers. J. Med. Prac. Under review.

- Makri, S.; Blandford, A. Coming Across Information Serendipitously: Part 1-A Process Model. J. Doc. 2012, 68, 684–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makri, S.; Blandford, A. Coming Across Information Serendipitously: Part 2-A Classification Framework. J. Doc. 2012, 68, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skains, L. Færwhile: A Journey through a Space of Time. Available online: http://lyleskains.com/Faerwhile.html (accessed on 21 February 2016).

- Skains, L. Awake the Mighty Dread. 2013. Available online: http://lyleskains.com/FW/Awake/index.html (accessed on 21 February 2016).

- Skains, L. Streams Slipping in the Dark. 2013. Available online: http://lyleskains.com/FW/Streams/index.html (accessed on 21 February 2016).

- Campbell, A. Fiction of Dreams; Presentation at Bangor University: Bangor, UK, 14 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Flower, L.; Hayes, J.R. Images, Plans, and Prose: The Representation of Meaning in Writing. Writ. Commun. 1984, 1, 120–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amegusa Bilbo’s Map of Eriador. Available online: http://amegusa.deviantart.com/art/Bilbo-s-Map-of-Eriador-80863819 (accessed on 21 February 2013).

- Rose, A. childhood dreamspace map. Available online: http://anna-terrible.deviantart.com/art/childhood-dreamspace-map-207434534 (accessed on 21 February 2013).

- Benjamin, W. A Glimpse into the World of Children’s Books. In Selected Writings: 1938-1940; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Lessig, L. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy; The Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gnu.org. The Free Software Definition. Available online: http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html (accessed on 11 October 2012).

- Salsita Software JavaScripting. Available online: http://javascripting.com (accessed on 10 March 2016).

- Reed, A.A. Creating Interactive Fiction with Inform7; Course Technology, Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, A.A. Sand-Dancer. Available online: http://aaronareed.net/sand-dancer-game/ (accessed on 11 October 2012).

- Montfort, N. Twisty Little Passages; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, R. Audience Inter/Active: Interactive Media, Narrative Control and Reconceiving Audience History. New Media Soc. 2006, 8, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creativecommons.org. Creative Commons. Available online: http://creativecommons.org/ (accessed on 11 October 2012).

- Connolly, K. Helene Hegemann: “There’s No Such Thing as Originality, Just Authenticity”. 2012. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/jun/24/helene-hegemann-axolotl-novelist-interview (accessed on 21 February 2016).

- Thomas, B. Fictional Dialogue: Speech and Conversation in the Modern and Postmodern Novel; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kittur, A. Collaboration and Creativity. XRDS 2010, 17, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).