A Hybrid BWM-GRA-PROMETHEE Framework for Ranking Universities Based on Scientometric Indicators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

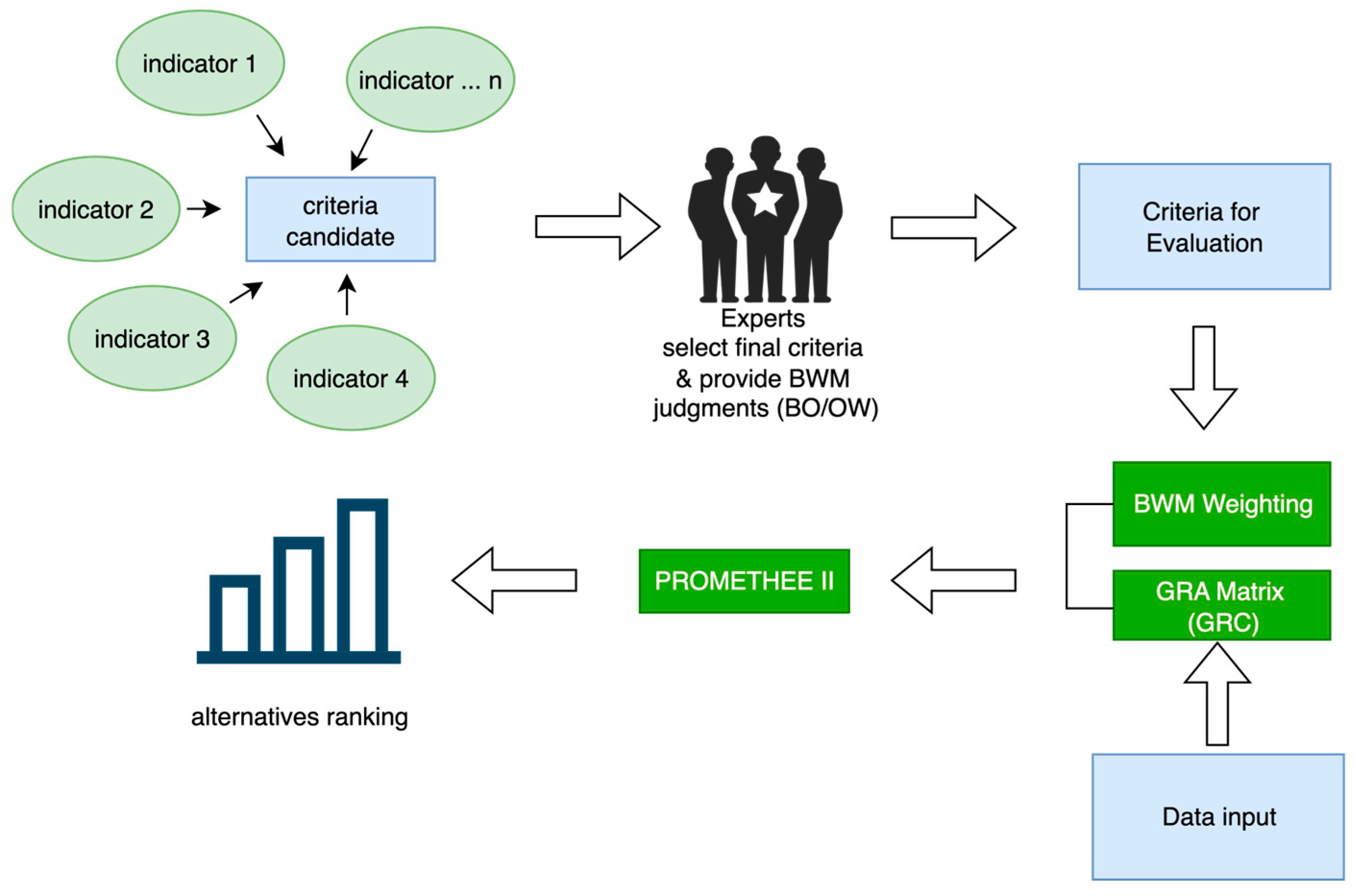

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Best-Worst Method (BWM)

Step 1: Pairwise Comparison

Step 2: Criteria Weights Calculation

Step 3: Consistency Assessment

Step 4: Aggregation of Individual Priorities

3.2.2. Grey Relational Analysis (GRA)

Step 1: Normalization

Step 2: Determination of the Reference Sequence

Step 3: Calculation of the Grey Relational Coefficient (GRC)

- Deviation from the ideal.For each entry, compute the absolute deviation from the ideal value, it is as follows:where represent the absolute deviation between the normalized performance value of an alternative and its ideal condition. The value 1 denotes the maximum value within the normalized (0, 1) scale. is the normalized performance of alternative under criterion obtained from by scaling the original data to the (0, 1) range.

- Global deviation boundaries.Determine the minimum and maximum deviation values across all alternatives and criteria.it is as follows:where denotes the smallest deviation within the entire matrix, indicating the point closest to the ideal condition. denotes the largest deviation, indicating the point farthest from the ideal. Both serve as global reference boundaries used to standardize the deviation range across the entire dataset.

- Grey Relational Coefficient (GRC)GRC converts the deviation value into a measure of relational closeness between each alternative and the ideal reference, expressed similar or dissimilar an alternatives performance to the ideal condition under each criterion. It is defined as follows:where denotes the grey relational coefficient of alternative under criterion . ζ is the distinguishing coefficient used to adjust the contrast level (Başaran & Ighagbon, 2024; Mahmoudi et al., 2020; Malekpoor et al., 2018). is the deviation from the ideal value for criterion j. and are the minimum and maximum deviations across all alternatives and criteria.

3.2.3. PROMETHEE II

Step 1: Pairwise Performance Difference

Step 2: Preference Function

Step 3: Aggregate Preference Index

Step 4: Leaving and Entering Flows

Step 5: Net Flow—Complete Ranking

4. Results

4.1. Result of Formulating the Criteria

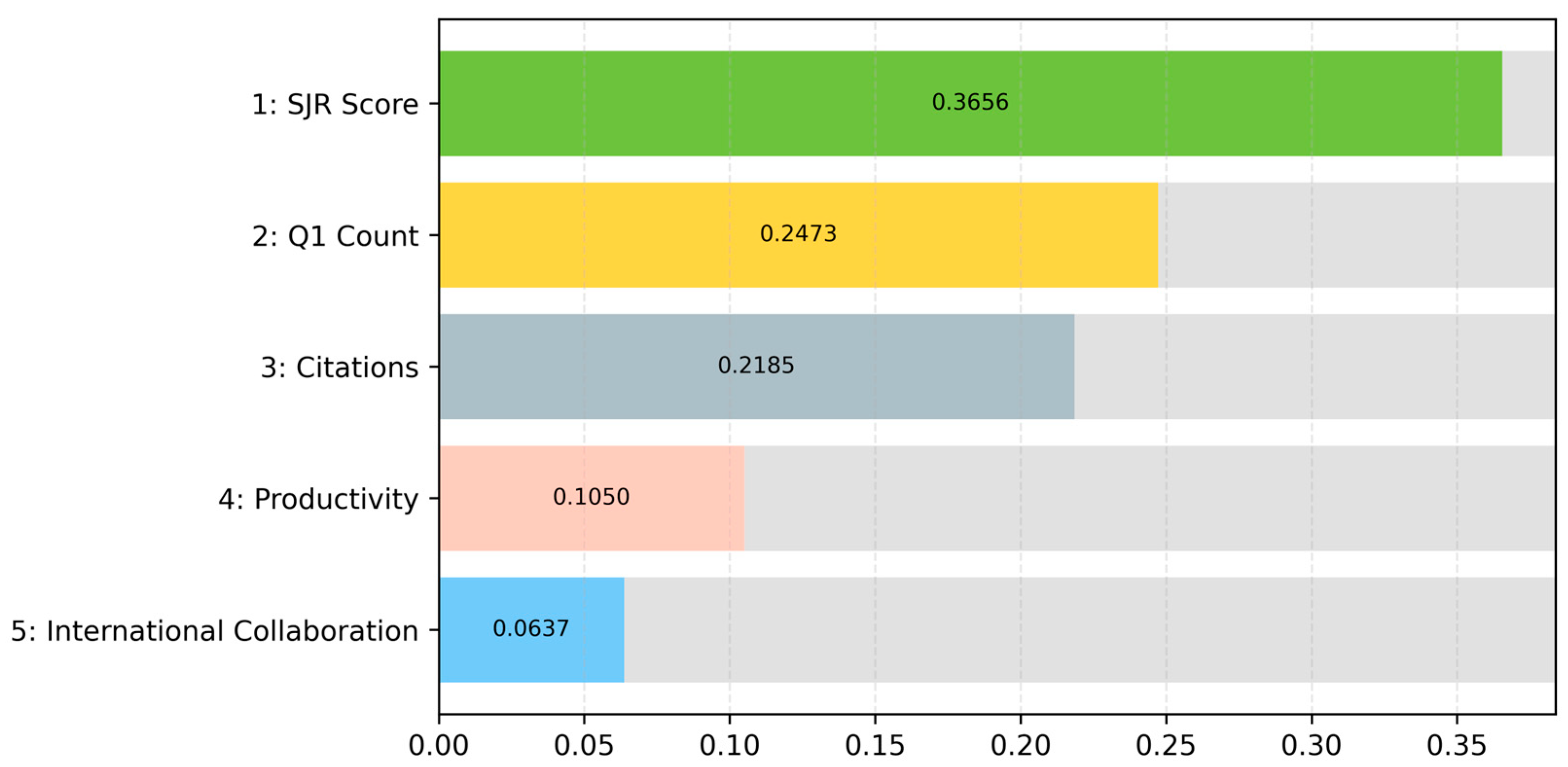

4.2. Criteria Weighting Using BWM

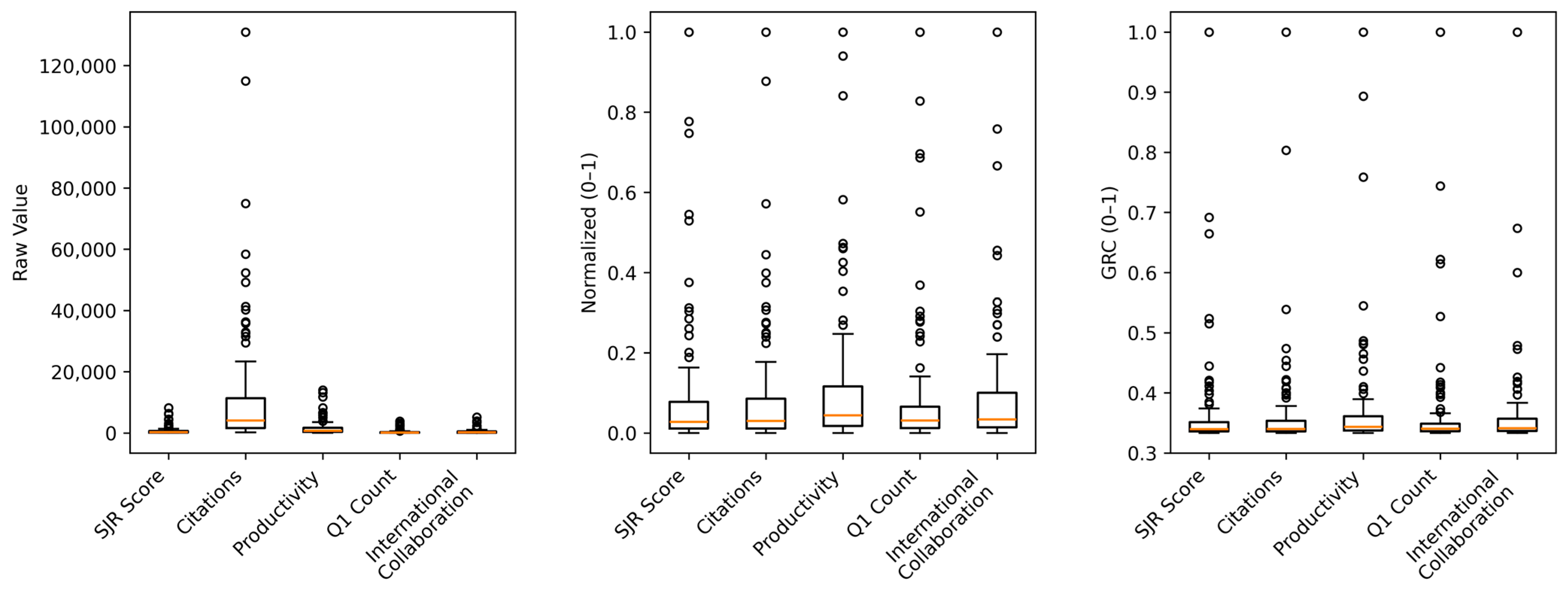

4.3. Results of Grey Relational Analysis

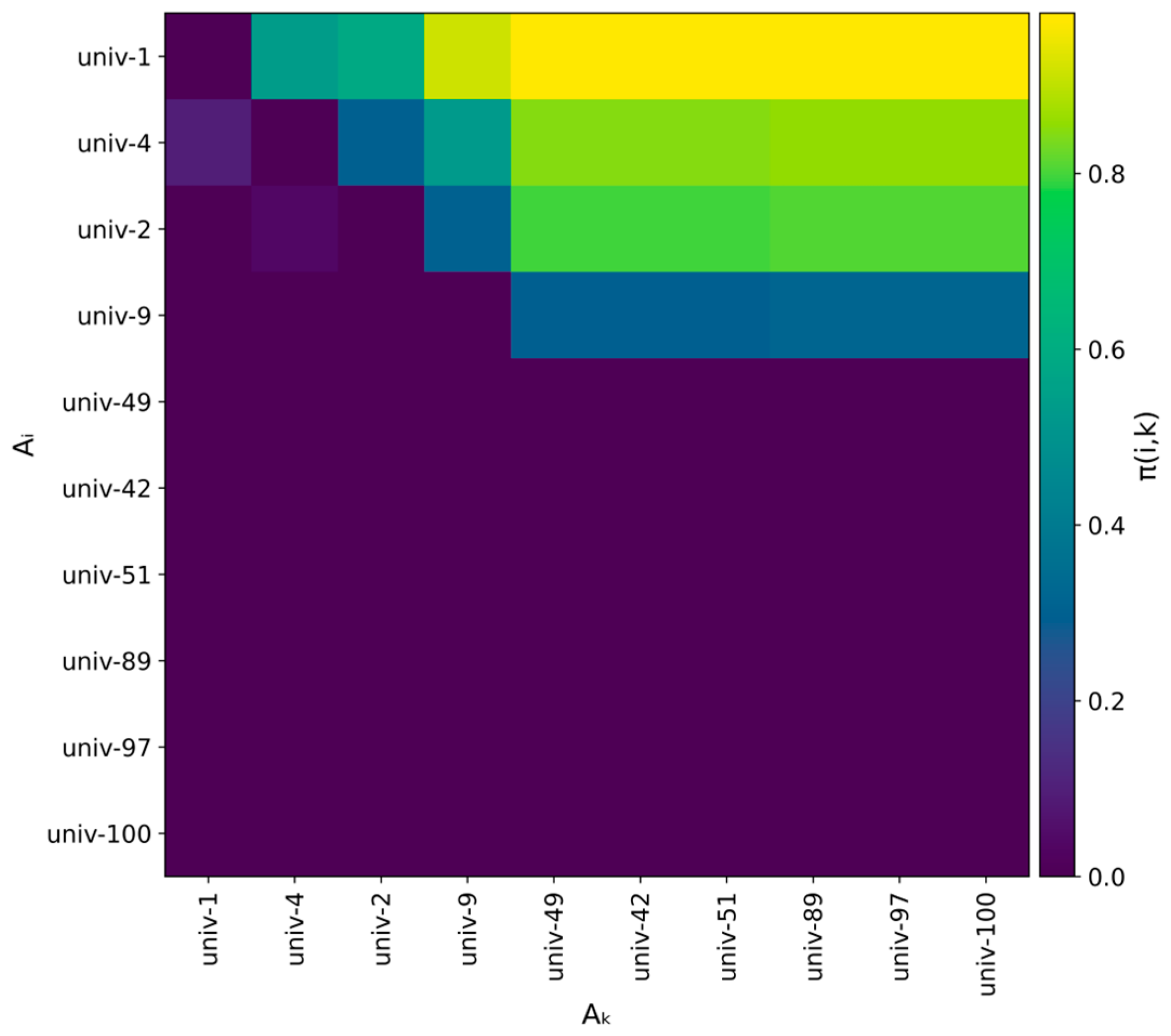

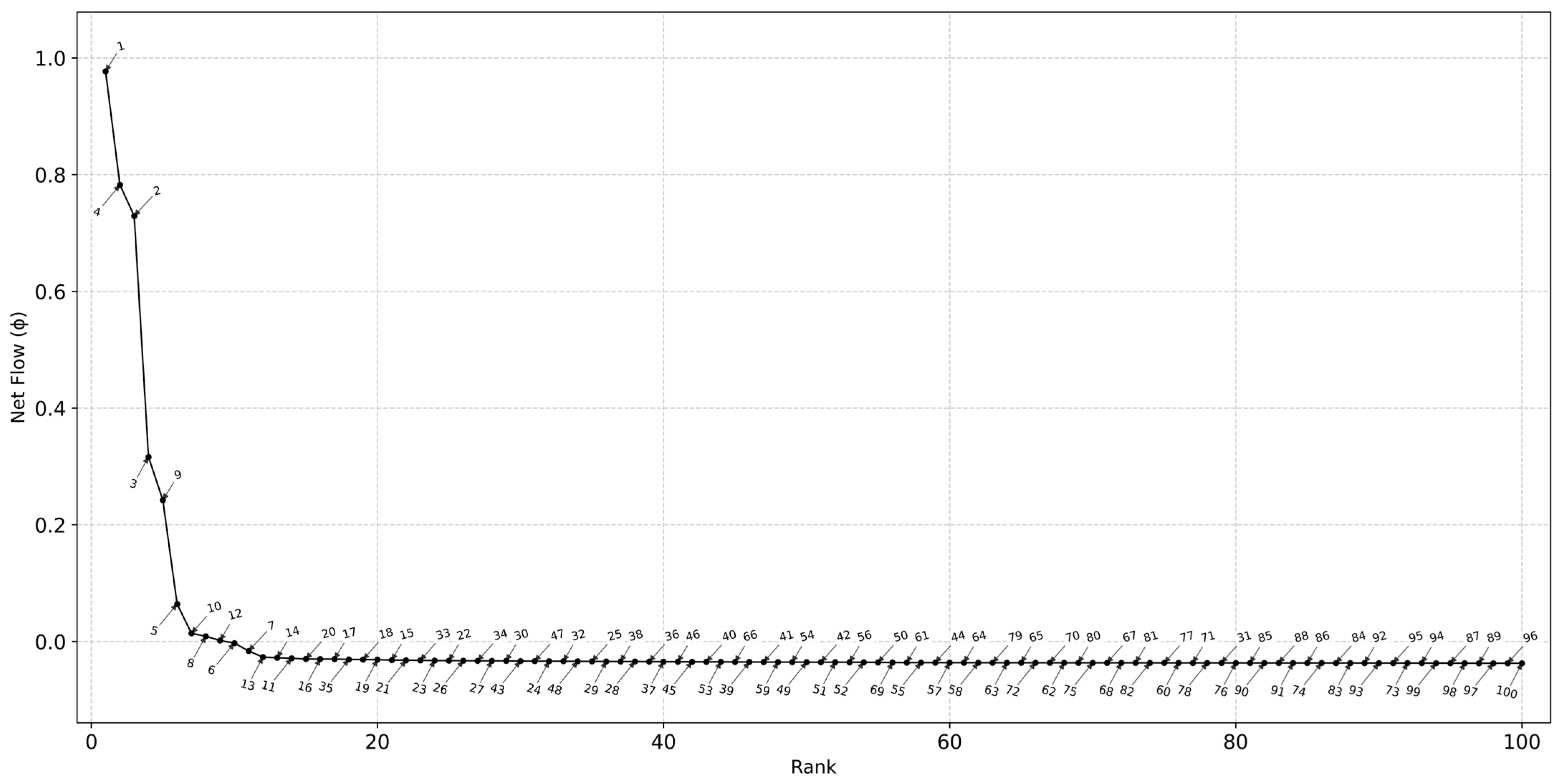

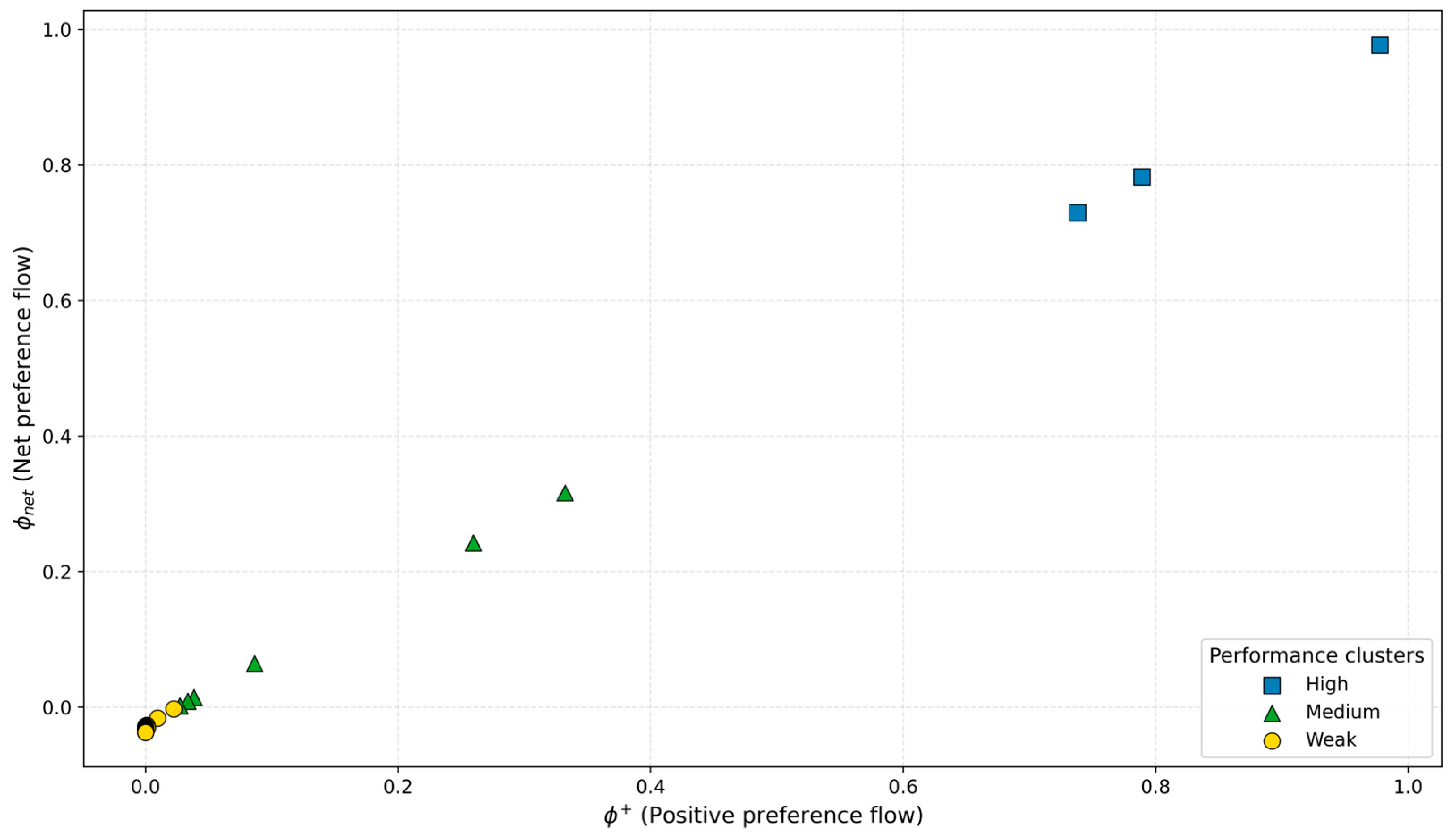

4.4. Results of PROMETHEE II

4.5. Validations

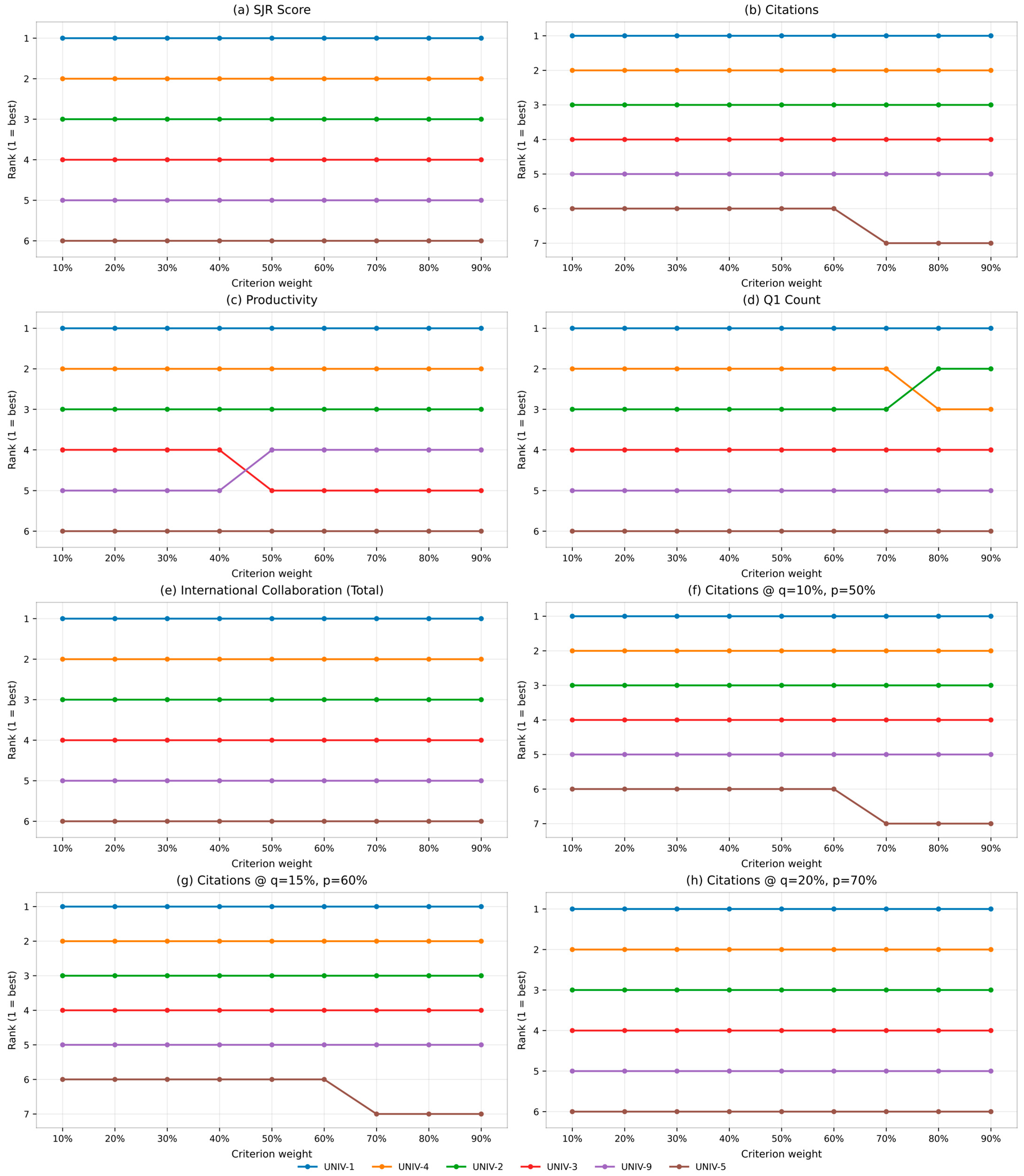

4.5.1. Sensitivity Analysis

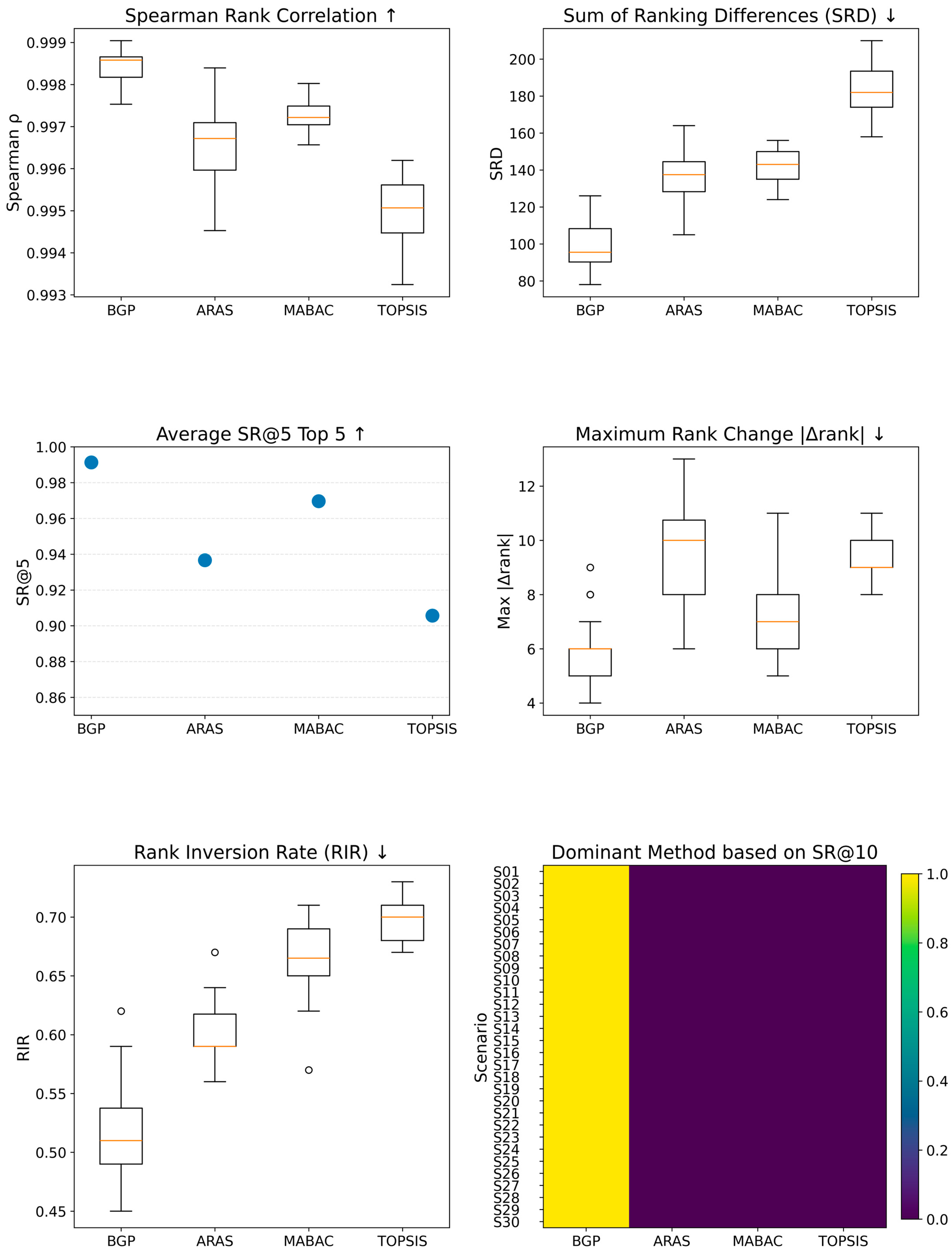

4.5.2. Comparative Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albadayneh, B. A., Alrawashdeh, A., Obeidat, N., Al-Dekah, A. M., Zghool, A. W., & Abdelrahman, M. (2024). Medical magnetic resonance imaging publications in Arab countries: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. Heliyon, 10(7), e28512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrababah, S. A. A., & Gan, K. H. (2023). Effects of the hybrid CRITIC–VIKOR method on product aspect ranking in customer reviews. Applied Sciences, 13(16), 9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, L., Gayathri, P., Karuveettil, V., & Anjali, M. (2024). Top 100 most cited economic evaluation papers of preventive oral health programmes: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research, 14(6), 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anculle-Arauco, V., Krüger-Malpartida, H., Arevalo-Flores, M., Correa-Cedeño, L., Mass, R., Hoppe, W., & Pedraz-Petrozzi, B. (2024). Content validation using Aiken methodology through expert judgment of the first Spanish version of the Eppendorf schizophrenia inventory (ESI) in Peru: A brief qualitative report. Spanish Journal of Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17(2), 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andjelković, D., Stojić, G., Nikolić, N., Das, D. K., Subotić, M., & Stević, Ž. (2024). A novel data-envelopment analysis interval-valued fuzzy-rough-number multi-criteria decision-making (DEA-IFRN MCDM) model for determining the efficiency of road sections based on headway analysis. Mathematics, 12(7), 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, B., Abacıoğlu, S., & Basilio, M. P. (2023). A comprehensive review of the novel weighting methods for multi-criteria decision-making. Information, 14(5), 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, E., Murat, M., Imamoglu, G., & Kose, Y. (2023). A novel hybrid MCDM approach to evaluate universities based on student perspective. Scientometrics, 128(1), 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başaran, S., & Ighagbon, O. A. (2024). Enhanced FMEA methodology for evaluating mobile learning platforms using grey relational analysis and fuzzy AHP. Applied Sciences, 14(19), 8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydaş, M., Yılmaz, M., Jović, Ž., Stević, Ž., Özuyar, S. E. G., & Özçil, A. (2024). A comprehensive MCDM assessment for economic data: Success analysis of maximum normalization, CODAS, and fuzzy approaches. Financial Innovation, 10(1), 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiderbeck, D., Frevel, N., von der Gracht, H. A., Schmidt, S. L., & Schweitzer, V. M. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the European football ecosystem—A Delphi-based scenario analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 165, 120577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L. (2024). Skewed distributions of scientists’ productivity: A research program for the empirical analysis. Scientometrics, 129(4), 2455–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L., & Williams, R. (2020). An evaluation of percentile measures of citation impact, and a proposal for making them better. Scientometrics, 124(2), 1457–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, J. P., & Vincke, P. (1985). Note—A preference ranking organisation method. Management Science, 31(6), 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Bulgarova, B. A., & Kumar, R. (2025). Prioritizing generative artificial intelligence co-writing tools in newsrooms: A hybrid MCDM framework for transparency, stability, and editorial integrity. Mathematics, 13(23), 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clermont, M., Krolak, J., & Tunger, D. (2021). Does the citation period have any effect on the informative value of selected citation indicators in research evaluations? Scientometrics, 126(2), 1019–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquelet, B., Dejaegere, G., & De Smet, Y. (2025). Evaluating the Promethee ii ranking quality. Algorithms, 18(10), 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraio, C., Di Leo, S., & Leydesdorff, L. (2023). A heuristic approach based on Leiden rankings to identify outliers: Evidence from Italian universities in the European landscape. Scientometrics, 128(1), 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, M., Jele, A., & Major, Z. B. (2022). The model of maximum productivity for research universities SciVal author ranks, productivity, university rankings, and their implications. Scientometrics, 127(8), 4335–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J., Zhan, J., & Wu, W. Z. (2022). A ranking method with a preference relation based on the PROMETHEE method in incomplete multi-scale information systems. Information Sciences, 608, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vico, G., Alves, C. J. R., Sellitto, M. A., & da Silva, D. O. (2025). Data-driven performance evaluation and behavior alignment in port operations: A multivariate analysis of strategic indicators. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, G., & Al, U. (2019). Is it possible to rank universities using fewer indicators? A study on five international university rankings. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 71(1), 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elevli, S., & Elevli, B. (2024). A study of entrepreneur and innovative university index by entropy-based grey relational analysis and PROMETHEE. Scientometrics, 129(6), 3193–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gibari, S., Gómez, T., & Ruiz, F. (2018). Evaluating university performance using reference point based composite indicators. Journal of Informetrics, 12(4), 1235–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbey, A., Fidan, Ü., & Gündüz, C. (2025). A robust hybrid weighting scheme based on IQRBOW and entropy for MCDM: Stability and advantage criteria in the VIKOR framework. Entropy, 27(8), 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esangbedo, M. O., & Wei, J. (2023). Grey hybrid normalization with period based entropy weighting and relational analysis for cities rankings. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 13797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezell, B., Lynch, C. J., & Hester, P. T. (2021). Methods for weighting decisions to assist modelers and decision analysists: A review of ratio assignment and approximate techniques. Applied Sciences, 11(21), 10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnè, M., & Vouldis, A. (2024). ROBOUT: A conditional outlier detection methodology for high-dimensional data. Statistical Papers, 65(4), 2489–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagolewski, M., Żogała-Siudem, B., Siudem, G., & Cena, A. (2022). Ockham’s index of citation impact. Scientometrics, 127(5), 2829–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Tian, T., & Wen, L. (2025). Study on outlier detection algorithm based on tightest neighbors. Expert Systems with Applications, 290, 128385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, F., Abdollahzadeh, V., & Zeinalnezhad, M. (2022). An integrated multi-criteria decision-making and multi-objective optimization framework for green supplier evaluation and optimal order allocation under uncertainty. Decision Analytics Journal, 4, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M., Celik, E., Gumus, A. T., & Guneri, A. F. (2018). A fuzzy logic based PROMETHEE method for material selection problems. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 7(1), 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M., & Yucesan, M. (2022). Performance evaluation of Turkish universities by an integrated Bayesian BWM-TOPSIS model. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 80, 101173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z., Liu, J., Liu, X., Meng, Z., Pu, M., Wu, H., Yan, X., Yang, G., Zhang, X., Chen, C., & Chen, F. (2024). An integrated MCDM model with enhanced decision support in transport safety using machine learning optimization. Knowledge-Based Systems, 301, 112286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2025). Revisiting the Delphi technique—Research thinking and practice: A discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 168, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesselink, G., Verhage, R., van der Horst, I. C. C., van der Hoeven, H., & Zegers, M. (2024). Consensus-based indicators for evaluating and improving the quality of regional collaborative networks of intensive care units: Results of a nationwide Delphi study. Journal of Critical Care, 79, 154440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z., Yan, R., & Wang, S. (2022). On the k-means clustering model for performance enhancement of port state control. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 10(11), 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A., Pickernell, D., Huang, S., & Senyard, J. M. (2020). Examining knowledge transfer activities in UK universities: Advocating a PROMETHEE-based approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 26(6), 1389–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A., & Resce, G. (2021). Best-Worst PROMETHEE method for evaluating school performance in the OECD’s PISA project. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 73, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H., Khan, A. A., Mishra, R. K., Ahmad, N., Chandan, V., Kolář, V., & Müller, M. (2025). Taguchi grey relational analysis (GRA) based multi response optimization of flammability, comfort and mechanical properties in station suits. Heliyon, 11(4), e42508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamwal, A., Agrawal, R., Sharma, M., & Kumar, V. (2021). Review on multi-criteria decision analysis in sustainable manufacturing decision making. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 14(3), 202–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju-Long, D. (1982). Control problems of grey systems. Systems & Control Letters, 1(5), 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, P. (2024). A scientometric analysis of multicriteria decision-making research. Journal of Decision Systems, 33(sup1), 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheybari, S., Javdanmehr, M., Rezaie, F. M., & Rezaei, J. (2021). Corn cultivation location selection for bioethanol production: An application of BWM and extended PROMETHEE II. Energy, 228, 120593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. (2024). Evaluation system of vocational education construction in China based on linked TOPSIS analysis. Heliyon, 10(21), e39369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P., Xu, Z., Wei, C., Bai, Q., & Liu, J. (2022). A novel PROMETHEE method based on GRA-DEMATEL for PLTSs and its application in selecting renewable energies. Information Sciences, 589, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Han, Z., Yazdi, M., & Chen, G. (2022). A CRITIC-VIKOR based robust approach to support risk management of subsea pipelines. Applied Ocean Research, 124, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Zhang, L. (2023). An ensemble outlier detection method based on information entropy-weighted subspaces for high-dimensional data. Entropy, 25(8), 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F., Brunelli, M., & Rezaei, J. (2020). Consistency issues in the best worst method: Measurements and thresholds. Omega, 96, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaymanta, C. H., Quiroz-de-García, R., Rivas-Villena, J. A., Rojas-Arroyo, A., & Gregorio-Chaviano, O. (2022). Relationship between collaboration and normalized scientific impact in South American public universities. Scientometrics, 127(11), 6391–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N., & Xu, Z. (2021). An overview of ARAS method: Theory development, application extension, and future challenge. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 36(7), 3524–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Z., & Fang, H. (2020). A comparison among citation-based journal indicators and their relative changes with time. Journal of Informetrics, 14(1), 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovakov, A., & Teixeira da Silva, J. A. (2025). Scientometric indicators in research evaluation and research misconduct: Analysis of the Russian university excellence initiative. Scientometrics, 130(3), 1813–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, N., & Tumbas, P. (2019). Indicators of global university rankings: The theoretical issues. Strategic Management, 24(3), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A., Javed, S. A., Liu, S., & Deng, X. (2020). Distinguishing coefficient driven sensitivity analysis of gra model for intelligent decisions: Application in project management. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 26(3), 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, A. A., & Abdulaal, R. M. S. (2023). A hybrid MCDM approach based on fuzzy MEREC-G and fuzzy RATMI. Mathematics, 11(17), 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekpoor, H., Chalvatzis, K., Mishra, N., Mehlawat, M. K., Zafirakis, D., & Song, M. (2018). Integrated grey relational analysis and multi objective grey linear programming for sustainable electricity generation planning. Annals of Operations Research, 269(1–2), 475–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maral, M. (2024). Examining the research performance of universities with multi-criteria decision-making methods. SAGE Open, 14(4), 21582440241300542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, I., Mišić, M., & Protić, J. (2023). Exploring high scientific productivity in international co-authorship of a small developing country based on collaboration patterns. Journal of Big Data, 10(1), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moslem, S., Farooq, D., Ghorbanzadeh, O., & Blaschke, T. (2020). Application of the AHP-BWM model for evaluating driver behavior factors related to road safety: A case study for Budapest. Symmetry, 12(2), 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhametzyanov, I., & Pamucar, D. (2018). A sensitivity analysisin mcdm problems: A statistical approach. Decision Making: Applications in Management and Engineering, 1(2), 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. K., & Nhieu, N. L. (2025). Comparative sustainability efficiency of G7 and BRICS economies: A DNMEREC-DNMARCOS approach. Mathematics, 13(22), 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivero, M. A., Bertolino, A., Dominguez-Mayo, F. J., Matteucci, I., & Escalona, M. J. (2022). A Delphi study to recognize and assess systems of systems vulnerabilities. Information and Software Technology, 146, 106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubahman, L., & Duleba, S. (2024). Fuzzy PROMETHEE model for public transport mode choice analysis. Evolving Systems, 15(2), 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, O. (2024). Assessment of the social progress on European Union by logarithmic decomposition of criteria importance. Expert Systems with Applications, 238, 121846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapostolou, A., Karakosta, C., Mexis, F. D., Andreoulaki, I., & Psarras, J. (2024). A fuzzy PROMETHEE method for evaluating strategies towards a cross-country renewable energy cooperation: The cases of Egypt and Morocco. Energies, 17(19), 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowski, B., Wątróbski, J., & Sałabun, W. (2025). Novel coefficients for improved robustness in multi-criteria decision analysis. Artificial Intelligence Review, 58(10), 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B., & Saha, I. (2018). Research rating: Some technicalities. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 78, S24–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulillo, A., Kim, A., Mutel, C., Striolo, A., Bauer, C., & Lettieri, P. (2021). Influential parameters for estimating the environmental impacts of geothermal power: A global sensitivity analysis study. Cleaner Environmental Systems, 3, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinochet, L. H. C., Moreira, M. Â. L., Fávero, L. P., dos Santos, M., & Pardim, V. I. (2023). Collaborative work alternatives with ChatGPT based on evaluation criteria for its use in higher education: Application of the PROMETHEE-SAPEVO-M1 method. Procedia Computer Science, 221, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, E., & Geldermann, J. (2024). PROMETHEE-Cloud: A web app to support multi-criteria decisions. EURO Journal on Decision Processes, 12, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, H. (2024). Using citation-based indicators to compare bilateral research collaborations. Scientometrics, 129(8), 4751–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, R. W. K., Szomszor, M., & Adams, J. (2022). Comparing standard, collaboration and fractional CNCI at the institutional level: Consequences for performance evaluation. Scientometrics, 127(12), 7435–7448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvera, E. V. J., & Lao, D. M. (2024, November 21–23). Enhancing deep learning-based breast cancer classification in mammograms: A multi-convolutional neural network with feature concatenation, and an applied comparison of best-worst multi-attribute decision-making and mutual information feature selections. 2024 9th International Conference on Intelligent Informatics and Biomedical Sciences (ICIIBMS) (pp. 511–518), Okinawa, Japan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raed, L., Mahdi, I., Ibrahim, H. M. H., Tolba, E. R., & Ebid, A. M. (2025). Innovative BWM–TOPSIS-based approach to determine the optimum delivery method for offshore projects. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S., Alali, A. S., Baro, N., Ali, S., & Kakati, P. (2024). A novel TOPSIS framework for multi-criteria decision making with random hypergraphs: Enhancing decision processes. Symmetry, 16(12), 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. (2015). Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. (2016). Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method: Some properties and a linear model. Omega, 64, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmer, J. (2025). Importance ranking of data and model uncertainties in quantile regression forest-based spatial predictions when data are sparse, imprecise and clustered. Ecological Informatics, 92, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlögl, C., Stock, W. G., & Reichmann, G. (2025). Scientometric evaluation of research institutions: Identifying the appropriate dimensions and attributes for assessment. Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice, 13(2), 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoch, U. (2020). Mean values of skewed distributions in the bibliometric assessment of research units. Scientometrics, 125(2), 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z. (2023). Use of Delphi in health sciences research: A narrative review. Medicine, 102(7), E32829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H., Huang, L., Li, K., Wang, X. H., & Liu, H. C. (2022). An extended multi-attributive border approximation area comparison method for emergency decision making with complex linguistic information. Mathematics, 10(19), 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szluka, P., Csajbók, E., & Győrffy, B. (2023). Relationship between bibliometric indicators and university ranking positions. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamak, S., Eslami, Y., & Da Cunha, C. (2025). Validation of multidimensional performance assessment models using hierarchical clustering. Expert Systems with Applications, 290, 128446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkayesh, A. E., Tirkolaee, E. B., Bahrini, A., Pamucar, D., & Khakbaz, A. (2023). A systematic literature review of MABAC method and applications: An outlook for sustainability and circularity. Informatica, 34(2), 415–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, B., Motahari-Nezhad, H., Horseman, N., Berek, L., Kovács, L., Hölgyesi, Á., Péntek, M., Mirjalili, S., Gulácsi, L., & Zrubka, Z. (2024). Ranking resilience: Assessing the impact of scientific performance and the expansion of the times higher education word university rankings on the position of Czech, Hungarian, Polish, and Slovak universities. Scientometrics, 129(3), 1739–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggle, C. R., MacDonald, R., Triggle, D. J., & Grierson, D. (2022). Requiem for impact factors and high publication charges. Accountability in Research, 29(3), 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trung Do, D. (2024). Assessing the impact of criterion weights on the ranking of the top ten universities in vietnam. Engineering, Technology and Applied Science Research, 14(4), 14899–14903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turskis, Z., & Keršulienė, V. (2024). SHARDA–ARAS: A methodology for prioritising project managers in sustainable development. Mathematics, 12(2), 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachowicz, T., & Roszkowska, E. (2025). Enhancing TOPSIS to evaluate negotiation offers with subjectively defined reference points. Group Decision and Negotiation, 34, 715–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watrianthos, R., Ritonga, W. A., Rengganis, A., Wanto, A., & Isa Indrawan, M. (2021). Implementation of PROMETHEE-GAIA method for lecturer performance evaluation. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1933(1), 012067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wątróbski, J. (2023). Temporal PROMETHEE II—New multi-criteria approach to sustainable management of alternative fuels consumption. Journal of Cleaner Production, 413, 137445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Han, X., Yang, Y., Hu, A., & Li, Y. (2025). A contribution-driven weighted grey relational analysis model and its application in identifying the drivers of carbon emissions. Expert Systems with Applications, 287, 128039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, C., Zapp, P., Schreiber, A., & Kuckshinrichs, W. (2021). Setting thresholds to define indifferences and preferences in promethee for life cycle sustainability assessment of European hydrogen production. Sustainability, 13(13), 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedjour, D., Yedjour, H., Amri, M. B., & Senouci, A. (2024). Rule extraction based on PROMETHEE-assisted multi-objective genetic algorithm for generating interpretable neural networks. Applied Soft Computing, 151, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T., Tang, Y., Cui, H., & Kang, B. (2025). A novel BWM-based conflict management method for interval-valued belief structure. Information Sciences, 721, 122617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudhoyono, A. H., Sukoco, B. M., Maharani, I. A. K., Putra, I. K., & Suhariadi, F. (2025). Bridging the gap: Indonesia’s research trajectory and national development through a scientometric analysis using SciVal. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 11(1), 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Jiang, N., Su, T., Chen, J., Streimikiene, D., & Balezentis, T. (2022). Spreading knowledge and technology: Research efficiency at universities based on the three-stage MCDM-NRSDEA method with bootstrapping. Technology in Society, 68, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Shi, J., & Situ, L. (2021). The correlation between author-editorial cooperation and the author’s publications in journals. Journal of Informetrics, 15(1), 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K., Fang, J., Li, J., Shi, H., Xu, Y., Li, R., Xie, R., & Cai, G. (2025). Robust grey relational analysis-based accuracy evaluation method. Applied Sciences, 15(9), 4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B., Wang, T., Liu, G., & Zhou, C. (2024). Revealing dynamic goals for university’s sustainable development with a coupling exploration of SDGs. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 22799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, P. (2022). Application framework of multi-criteria methods in sustainability assessment. Energies, 15(23), 9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoraghi, N., Amiri, M., Talebi, G., & Zowghi, M. (2013). A fuzzy MCDM model with objective and subjective weights for evaluating service quality in hotel industries. Journal of Industrial Engineering International, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, Ž., Nikolić, D., Savić, M., Djordjević, P., & Mihajlović, I. (2017). Prioritizing strategic goals in higher education organizations by using a SWOT–PROMETHEE/GAIA–GDSS model. Group Decision and Negotiation, 26(4), 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Indicator | Category | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of Publications (Productivity) | Productivity | Total Document Published (T. Zhang et al., 2021). |

| 2 | Number of Citations (Citations) | Citations | Total citations received by all publications (T. Zhang et al., 2021; Clermont et al., 2021). |

| 3 | International Collaboration | Networking | Publications authored by researchers from two or more different countries (Mitrović et al., 2023). |

| 4 | h-index | Citations | The h-index value, where h publications have received ≥ h citations each (Paul & Saha, 2018). |

| 5 | g-index | Citations | assesses research impact with emphasis on highly cited articles (Paul & Saha, 2018). |

| 6 | Category Normalized Citation Impact (CNCI) | Citations | compares a paper’s citation impact to the global average in the same field and year (Potter et al., 2022). |

| 7 | Field-Weighted Citation Impact (FWCI) | Citations | indicates citation impact normalized to global field performance (H. Pohl, 2024). |

| 8 | Publications in Top Journal (Q1 Count) | Quality | Total publications in Q1 journals (Tóth et al., 2024). |

| 9 | Publications in Top Cited (top10%) | Citations | The percentage of publications ranked within the top 10% most cited in their field (Bornmann & Williams, 2020). |

| 10 | Number of Cited Publications | Citations | Number of publication with ≥ 1 citation (Albadayneh et al., 2024). |

| 11 | Percentage of Cited Publications | Citations | the proportion of papers within the global top 10% by citations (Anand et al., 2024). |

| 12 | Journal Impact Factor (JIF) | Impact Metrics | The average two-year citation rate per journal article (Triggle et al., 2022). |

| 13 | SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) Score | Impact Metrics | A journal prestige index weighted by citation network connectivity (Limaymanta et al., 2022). |

| 14 | Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP) | Impact Metrics | Field-normalized citation impact based on disciplinary citation patterns (X. Z. Liu & Fang, 2020). |

| a_BW | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| CI | 0.00 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 1.63 | 2.30 | 3.00 | 3.73 | 4.47 | 5.23 |

| Criteria | Median | IQR | Aiken’s V | Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Productivity | 8 | 0.5 | 0.839 | Valid |

| Citations | 8 | 1 | 0.821 | Valid |

| International Collaboration | 8 | 1 | 0.929 | Valid |

| Q1 Count | 9 | 1 | 0.946 | Valid |

| SJR Score | 9 | 0.5 | 0.964 | Valid |

| Expert | Best Criteria | Worst Criteria | SJR Score a | Intl Collab a | Citations a | Q1 Count a | Productivity a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SJR Score | Intl Collab | 1/8 | 8/1 | 3/4 | 2/6 | 4/3 |

| 2 | SJR Score | Intl Collab | 1/7 | 7/1 | 4/4 | 3/5 | 5/3 |

| 3 | Q1 Count | Intl Collab | 2/5 | 7/1 | 3/4 | 1/6 | 4/3 |

| 4 | SJR Score | Intl Collab | 1/9 | 9/1 | 5/4 | 4/5 | 6/3 |

| 5 | Citations | Intl Collab | 3/4 | 8/1 | 1/7 | 4/3 | 5/4 |

| 6 | SJR Score | Productivity | 1/7 | 5/3 | 3/4 | 4/5 | 7/1 |

| 7 | Q1 Count | Intl Collab | 3/4 | 8/1 | 2/5 | 1/6 | 5/3 |

| Expert | Best Criteria | Worst Criteria | a_BW | CI_Max | ξ* | CR | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SJR Score | Intl Collab | 8 | 4.47 | 0.0480 | 0.0107 | Consistent |

| 2 | SJR Score | Intl Collab | 7 | 3.73 | 0.0910 | 0.0244 | Consistent |

| 3 | Q1 Count | Intl Collab | 7 | 3.73 | 0.0694 | 0.0186 | Consistent |

| 4 | SJR Score | Intl Collab | 9 | 5.23 | 0.0933 | 0.0178 | Consistent |

| 5 | Citations | Intl Collab | 8 | 4.47 | 0.1018 | 0.0228 | Consistent |

| 6 | SJR Score | Productivity | 7 | 3.73 | 0.1138 | 0.0305 | Consistent |

| 7 | Q1 Count | Intl Collab | 8 | 4.47 | 0.0750 | 0.0168 | Consistent |

| No | Criteria | Exp1 | Exp2 | Exp3 | Exp4 | Exp5 | Exp6 | Exp7 | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SJR Score | 0.4320 | 0.4889 | 0.2428 | 0.5515 | 0.1957 | 0.4813 | 0.1667 | 0.3656 |

| 2 | International Collaboration | 0.0480 | 0.0569 | 0.0578 | 0.0509 | 0.0548 | 0.1190 | 0.0583 | 0.0637 |

| 3 | Citations | 0.1600 | 0.1450 | 0.1618 | 0.1290 | 0.4853 | 0.1984 | 0.2500 | 0.2185 |

| 4 | Q1 Count | 0.2400 | 0.1933 | 0.4162 | 0.1612 | 0.1468 | 0.1488 | 0.4250 | 0.2473 |

| 5 | Productivity | 0.1200 | 0.1160 | 0.1214 | 0.1075 | 0.1174 | 0.0525 | 0.1000 | 0.1050 |

| Alternative | SJR Score | Citations | Productivity | Q1 Count | Intl Collab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNIV-1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.940 | 1.000 | 0.758 |

| UNIV-4 | 0.748 | 0.878 | 1.000 | 0.687 | 1.000 |

| UNIV-2 | 0.777 | 0.572 | 0.841 | 0.828 | 0.666 |

| UNIV-3 | 0.545 | 0.445 | 0.473 | 0.696 | 0.456 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| UNIV-97 | 0.000 | 0.0047 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0046 |

| Alternative | SJR Score | Citations | Productivity | Q1 Count | Intl Collab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNIV-1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.893 | 1.000 | 0.674 |

| UNIV-4 | 0.664 | 0.803 | 1.000 | 0.615 | 1.000 |

| UNIV-2 | 0.692 | 0.539 | 0.759 | 0.744 | 0.600 |

| UNIV-3 | 0.524 | 0.474 | 0.487 | 0.622 | 0.479 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| UNIV-97 | 0.3333 | 0.3344 | 0.3335 | 0.3333 | 0.3344 |

| Aᵢ (Compared to) | U-1 | U-4 | U-2 | U-9 | U-49 | U-42 | U-51 | U-89 | U-97 | U-100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNIV-1 | - | 0.6165 | 0.6467 | 0.9458 | 0.9871 | 0.9873 | 0.9872 | 0.9886 | 0.9884 | 0.9886 |

| UNIV-4 | 0.0622 | - | 0.2484 | 0.4600 | 0.8238 | 0.8239 | 0.8250 | 0.8361 | 0.8365 | 0.8356 |

| UNIV-2 | 0.0000 | 0.0465 | - | 0.3016 | 0.7884 | 0.7889 | 0.7876 | 0.8006 | 0.8003 | 0.8010 |

| UNIV-9 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | - | 0.2938 | 0.2940 | 0.2940 | 0.3145 | 0.3145 | 0.3146 |

| UNIV-49 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | - | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| UNIV-42 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | - | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| UNIV-51 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | - | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| UNIV-89 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | - | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| UNIV-97 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | - | 0.0000 |

| UNIV-100 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | - |

| Ranked Top-10 of 100 | Ranked Bottom-10 of 100 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Universities | ϕ+ | ϕ− | ϕ | Rank | Universities | ϕ+ | ϕ− | ϕ |

| 1 | UNIV-1 | 0.977659 | 0.000629 | 0.97703 | 91 | UNIV-95 | 0 | 0.037027 | −0.03703 |

| 2 | UNIV-4 | 0.789071 | 0.006698 | 0.782374 | 92 | UNIV-73 | 0 | 0.037032 | −0.03703 |

| 3 | UNIV-2 | 0.738242 | 0.009042 | 0.7292 | 93 | UNIV-94 | 0 | 0.037051 | −0.03705 |

| 4 | UNIV-3 | 0.33234 | 0.016097 | 0.316244 | 94 | UNIV-99 | 0 | 0.037066 | −0.03707 |

| 5 | UNIV-9 | 0.259778 | 0.017457 | 0.24232 | 95 | UNIV-87 | 0 | 0.037169 | −0.03717 |

| 6 | UNIV-5 | 0.086428 | 0.02222 | 0.064207 | 96 | UNIV-98 | 0 | 0.037233 | −0.03723 |

| 7 | UNIV-10 | 0.038418 | 0.02434 | 0.014078 | 97 | UNIV-89 | 0 | 0.037292 | −0.03729 |

| 8 | UNIV-8 | 0.033586 | 0.024709 | 0.008877 | 98 | UNIV-97 | 0 | 0.037298 | −0.0373 |

| 9 | UNIV-12 | 0.027195 | 0.025454 | 0.001742 | 99 | UNIV-96 | 0 | 0.037301 | −0.0373 |

| 10 | UNIV-6 | 0.022283 | 0.025071 | −0.00279 | 100 | UNIV-100 | 0 | 0.037312 | −0.03731 |

| Method | Spearman’s ↑ | SRD ↓ | SR@5 ↑ | Max ΔRank ↓ | RIR ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGP | 0.9985 | 98.7 | 0.99 | 5.73 | 0.52 |

| ARAS | 0.9966 | 134.6 | 0.94 | 9.70 | 0.60 |

| MABAC | 0.9973 | 142.0 | 0.97 | 7.23 | 0.67 |

| TOPSIS | 0.9950 | 183.1 | 0.91 | 9.60 | 0.70 |

| Statistic | X2 | df | p-Value | N (Block) | CD0.05 | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 82.03 | 3 | 1.13 × 10−17 | 30 | 1.211 | Significant |

| Method i | Method j | Avg Rank Difference | CD0.05 | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGP | ARAS | 1.612 | 1.211 | Significant |

| BGP | MABAC | 1.700 | 1.211 | Significant |

| BGP | TOPSIS | 2.967 | 1.211 | Significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kurniadi, D.; Gernowo, R.; Surarso, B. A Hybrid BWM-GRA-PROMETHEE Framework for Ranking Universities Based on Scientometric Indicators. Publications 2026, 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications14010005

Kurniadi D, Gernowo R, Surarso B. A Hybrid BWM-GRA-PROMETHEE Framework for Ranking Universities Based on Scientometric Indicators. Publications. 2026; 14(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications14010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurniadi, Dedy, Rahmat Gernowo, and Bayu Surarso. 2026. "A Hybrid BWM-GRA-PROMETHEE Framework for Ranking Universities Based on Scientometric Indicators" Publications 14, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications14010005

APA StyleKurniadi, D., Gernowo, R., & Surarso, B. (2026). A Hybrid BWM-GRA-PROMETHEE Framework for Ranking Universities Based on Scientometric Indicators. Publications, 14(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications14010005